Chapter 52 Midwifery supervision and clinical governance

Supervision of midwives empowers midwives to work within the full scope of their role, provides professional support for midwives, promotes good midwifery practice and protects the public by providing a framework for scrutiny of professional standard practice (NMC 2002). It facilitates a non-confrontational, confidential, midwife-led review of a midwife’s level of knowledge, understanding and competence (ENB 1999). The philosophy of midwifery supervision and the standards it develops, reflect the key themes of clinical governance described in NHS First Class Service (DH 1998). These themes are:

Supervision of midwives

A short history of the supervision of midwives

Supervision of midwives was introduced in Edwardian times with the passing of the Midwives Act in 1902. Under the Act, the Central Midwives Board (CMB) was established and through that Board, the inspection of midwives. The inspectors of midwives so created were not practising midwives, as the supervisors of midwives are today, but middle class women, ‘ladies’, used to supervising subordinates (Kirkham 1995), and who had domestic standards much higher than those of the working class midwives. As a result, they were extremely critical of the poor environments in which many of the midwives then lived. These lady inspectors attempted to impose their middle class standards on the midwives, and had little understanding of the needs of midwives who had to undertake the domestic work in their own homes themselves. They expected the midwives to ‘use plenty of clean linen’ (Kirkham 1995) despite the fact that the women they attended could not afford such linen. Similarly, the midwives struggled to comply with the Midwives Rules that instructed them to summon medical aid even though there was no possibility of the family paying the doctor’s fee. It was not until 1918 that this matter was resolved when a further Midwives Act required midwives to notify the Local Supervising Authority (LSA), via the supervisor of midwives, that they had summoned medical aid. If summoned by a midwife the GP could be paid.

The LSA Officers were the Medical Officers of Health. They passed on the bulk of their LSA work to non-medical inspectors who were at liberty to inspect the midwives in any way they felt appropriate. They could follow them on their rounds, visit their homes, question the patients they had cared for and even investigate their personal lives (Kirkham 1995), in addition to inspecting their equipment. Records could not be checked; they were rarely made as many midwives were illiterate, notwithstanding their immense practical knowledge and independence. Midwives who disobeyed or ignored the rules would be disciplined. The Midwives Act also called for the LSA to investigate midwives who were guilty of negligence, malpractice or misconduct, personal or professional, and to report these midwives to the CMB for disciplinary action. The LSA Officer had to report any midwife convicted of an offence, suspend a midwife from practice if likely to be a source of infection, report the death of any midwife and submit a roll of midwives annually to the Board.

The roll of midwives was introduced with the 1902 Act that demanded the registration of midwives. Midwives must have their names on the roll of midwives, in order to continue practising. Training for midwives was established at the same time, but it was not until the 1910 Act that registration was permitted only on successful completion of an approved training course for midwives. Despite the training, it was not until 1936 that another revision of the Midwives Act led to the LSA being required to provide a salaried midwifery service. The amended Act empowered the CMB to set rules requiring midwives to attend refresher courses. It also determined the qualifications required to be a supervisor. Medical supervisors had to be medical officers, and non-medical supervisors, midwives, the latter under the control of the former. By 1937, the Ministry of Health had recognized the difficulties that midwives were experiencing by not having been supervised by midwives, and these changes were detailed in a Ministry of Health letter (MoH 1937), changing the title from inspector of midwives to supervisor of midwives, and requiring the supervisors to be experienced midwives. For some reason, it was thought appropriate that they should not be engaged in midwifery practice. A real change of heart had taken place since the 1902 Act, as the letter referred to the supervisor of midwives as ‘counsellor and friend’ rather than ‘relentless critic’ and expected the supervisor to display ‘sympathy and tact’.

Further revisions of the Midwives Act took place and in 1951 the most significant change wrought was for supervisors of midwives to ensure that midwives attended statutory refresher courses and to supply the names of those midwives who should attend. This statutory requirement continued until 2001 when rule 37 of the Midwives Rules (UKCC 1998) was superseded by Post-Registration Education and Practice (PREP) requirements (UKCC 1997). The PREP requirements detailed a gradual programme of change that would be completed in 2001.

Supervision of midwives did not move away from the auspices of the Medical Officers of Health until 1974 when the National Health Service (Reorganization) Act nominated Regional Health Authorities as LSA, and District Health Authorities nominated supervisors of midwives for appointment by the LSA. In 1977, the medical supervisor role was finally abolished and all supervisors were required to be practising midwives. The reorganization also led to supervision being introduced into the hospital environment as well as in the community. In 1979 the framework for the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC) and the National Boards of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland was established. The National Boards were required to provide advice and guidance to the LSA, leading to the abolition of the Central Midwives Board (CMB) in 1983.

Courses for supervisors of midwives were not introduced until 1978 when induction courses became a requirement for any supervisor of midwives appointed after 1974. The CMB introduced the first induction course that year; it was a 2-day course to be undertaken within the first year of appointment by the LSA. Today, these courses are much more rigorous and undertaken at first degree or masters level. Midwives must complete the course successfully before being eligible for appointment as a supervisor of midwives. The requirement for training as a supervisor of midwives prior to appointment did not exist until as recently as 1992 when the English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (ENB) developed an Open Learning Programme (ENB 1992). In 1993, the revised Midwives Rules (Rule 44(2) UKCC 1993) stipulated that this preparation take place prior to appointment, meaning that all four UK countries had to introduce training for supervisors, but only England and Wales used the ENB Open Learning Programme with associated study days. Scotland and Ireland had a less structured training which has become more rigorous over recent years.

In 1994, the Midwives Code of Practice (UKCC 1994) was revised to include a section which emphasized the relationship between midwife and supervisor of midwives as a partnership, rather than as one of controlling. In 1998 the UKCC amended the Midwives Rules and Code of Practice, now a combined document, changing rule 44 to address both preparation and updating for supervisors of midwives (UKCC 1998).

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) was established in 2002 when the UKCC ceased to exist and the National Boards were abolished. New ‘Midwives rules and standards’ (NMC 2004) were produced, dropping the ‘Code of Practice’ for midwives. Within these rules, supervision is addressed much more robustly, demonstrating greater commitment to the supervision of midwives. Although these revised rules did not provide much new detail about the preparation and updating of supervisors of midwives, a new publication, ’standards for the preparation and practice of supervisors of midwives’, (NMC 2006a) covers both of these matters in great detail.

The introduction of supervision of midwives in 1902 resulted in improvement in standards in midwifery and created a situation in which women were exposed to safe practitioners. Midwives were obliged to notify their intention to practise each year so that the roll of midwives was regularly updated and monitored. The midwifery inspectors could report to the LSA Officer midwives whose standards were considered unsatisfactory and who were considered dangerous to the public. In such cases, the LSA Officer could suspend the midwife from practice. Many of these functions continue today, although in a much more supportive fashion. The principal function of supervisors of midwives continues to be the protection of the public, but the main ethos is support for midwives. Midwives still have to notify their intention to practise midwifery each year to the LSA, and each LSA office maintains a database of all midwives practising within the LSA area. Information from the notifications of intention to practise is added to the details of registration on the NMC register.

Supervision of midwives in the twenty-first century

Midwives today enjoy the benefits of having a named supervisor of midwives to whom they can relate and look to for support, and with whom they can share their concerns. Among the competencies for a supervisor of midwives listed in the ’standards for the preparation and practice of supervisors of midwives’ (NMC 2006a) is ‘working in partnership with women’. This endorses the need for midwives and supervisors of midwives to work towards a common aim of providing the best possible care for mothers and babies and there is a mutual responsibility for effective communication between them.

There is always a supervisor of midwives on call at any time who can be contacted if there are any practice concerns, or if there has been a critical incident. There are certain times when a supervisor of midwives must be called, such as in the event of an unexpected stillbirth, although this is no longer listed as a requirement in the Midwives rules and standards (NMC 2004). This is still an expectation and appears within most LSA Guidelines. There is more than one reason for this. From a regulatory point of view, the supervisor of midwives needs to be sure that there was no sub-standard practice leading to the unexplained stillbirth. Equally important is the supervisor of midwives’ role in supporting the midwife who has been through this very sad and traumatizing experience.

Record-keeping in midwifery must be accurate, contemporaneous and provide a good account of care planning, treatment and delivery (NMC 2005). Supervisors of midwives are responsible for ensuring good record-keeping standards. They regularly check the midwifery records at their Trust, and feed back to midwives on their standards of record-keeping. This assists midwives in perfecting their notes and helps them to avoid problems which could lead to litigation.

The Midwives rules and standards (NMC 2004) still refer to the inspection of equipment and premises, but much less heed is paid to inspecting the bags of community midwives than was the case in earlier years. Much more emphasis is placed on discussion, support and professional development needs and being there for the midwives when they are in need, providing a confidential framework for a supportive relationship. A comprehensive list of the activities of a supervisor of midwives appears in Box 52.1.

Supervisory reviews

The annual supervisory review provides dedicated time for midwives to sit down with their supervisors of midwives and reflect on their practice over the preceding year. If midwives are concerned about any aspects of their practice they can discuss this frankly with their supervisor within the confidential environment of the supervisory review knowing that they will be offered support and guidance, rather than criticism.

Although it is customary for only one supervisory review a year, this is not fixed in tablets of stone and midwives are able to access their supervisor of midwives as, and when, they need or want to. As many supervisors of midwives hold clinical posts, they often work alongside the midwives they supervise and have more regular contact on an informal basis.

Critical incidents

If midwives have been involved in critical incidents, they will be encouraged to meet with their supervisor and reflect on the incidents, the events leading up to the incidents and the outcomes. The named supervisor of midwives is there to support the midwife, and acts on behalf of the LSA, not the Trust. If the incident is sufficiently serious, another supervisor of midwives may be asked to carry out a supervisory enquiry, again on behalf of the LSA, but a midwifery manager might undertake a management enquiry on behalf of the Trust. The named supervisor will support the midwife throughout the enquiry and will help to identify any weaknesses in practice and ascertain if there were any knowledge gaps. Such gaps can then be addressed through appropriate learning, and a learning contract can be prepared to address these deficiencies, supported by the supervisor of midwives. The contract will have a specific time frame, and regular meetings with the named supervisor to monitor progress will be accommodated. An appropriate mentor of the midwife’s choice will be allocated to support the midwife in the work area and there will be liaison with the head of midwifery education at the local university if academic input is required. These are the only individuals who need to be aware of the difficulties that the midwife has experienced, and every effort will be made by these people to maintain confidentiality at all times to protect the integrity of the midwife concerned.

Local supervising authorities

A practising midwife, with experience as a supervisor of midwives, performs the local supervising authority midwifery officer role in every LSA. Following reorganizations of health authorities in England earlier (DOH 2001A) on 1 July 2006, the number reduced to 10 strategic health authorities. There are, at the time of writing, just 10 LSAs in England with one LSAMO for each.

Until recently, in the other UK countries the LSA responsible officer was not necessarily a midwife. In Scotland, there were 16 link supervisors of midwives who performed much of the LSA function for the health board LSA officers who were not midwives, as well as carrying out their substantive posts, which were usually head of midwifery. In 2006, this changed with LSA midwifery officers being appointed in accordance with the Nursing and Midwifery Order (2001) (DH 2001b). There are now three LSA midwifery officers covering the health boards which have been grouped into three consortia of local supervising authorities for Scotland.

In Wales, the health authorities had appointed practising midwives, similar to the Scottish system, but the midwives were referred to as ‘lead supervisors of midwives’. There were four senior midwives appointed as lead supervisors of midwives to cover the LSA function in five health authorities, with one of the lead midwives taking responsibility for two health authorities. In 2002, the health authorities were abolished and the National Assembly for Wales designated Health Professions Wales as the local supervising authority. Two LSA midwifery officers were appointed to be responsible for the LSA standards in Wales. In 2006, the Welsh Assembly Government abolished Health Professions Wales and the functions of the LSA were transferred to Health Inspectorate Wales where the two LSAMOs continue their roles covering the whole country.

In Northern Ireland, the four health boards had link supervisors of midwives to carry out the LSA function on behalf of the non-midwife LSA officers at the health boards. The LSA officers were, in fact, directors of nursing. The link supervisors were from a Trust in each health board area (Duerden 2000a). This changed in 2005 with the appointment of an LSA midwifery officer to cover three of the health boards. At last, dedicated time is given to the LSA role in Northern Ireland, but still on a part-time basis. The fourth health board is still awaiting cover at the time of writing.

The LSA role has no management responsibility to Trusts, but it acts as a focus for issues relating to midwifery practice (ENB 1999) and its strength lies in its influence on quality in local midwifery services. All LSAMOs have to be aware of the wider NHS picture and contemporary issues. The UK wide National Forum of LSA Midwifery Officers meets every 2 months to ensure a national framework in which the midwifery officers can contribute informed advice on issues impacting on midwifery, such as structures for local maternity services and post-registration education for midwives.

The Nursing and Midwifery Order (2001) states that each LSA shall:

All of these aspects are clarified within the Midwives rules and standards (NMC 2004) and make much easier reading and comprehension. There is also further detail within this chapter to assist the reader and a list of the duties of an LSA midwifery officer in Box 52.2.

Box 52.2 Duties of the LSA midwifery officer

Risk management and the supervision of midwives

Chapter 53 specifically relates to risk management. All of the functions of a supervisor of midwives could be considered to have a risk management element as the framework for supervision is based on safety and good outcomes. The supervisor of midwives acts as an advocate for the consumer by monitoring the professional performance of midwives; thereby ensuring a safe standard of midwifery practice and enhancing the quality of care for a mother and her family. Supervision is a separate function from the management of the midwifery service and, although some supervisors may have responsibility for both, their responsibility for supervision is to the LSA.

Supervisors of midwives, in fulfilling their role of protecting the public, must be aware of the current safety culture in their units and be prepared to inform Trust executives of the risks being taken by staffing their maternity unit both inadequately and inappropriately.

The safety culture of the midwifery profession is bound by the Midwives rules and standards (NMC 2004) and the NMC Code (2008), by which all midwives must abide. The NMC code requires registrants to only undertake practice and accept responsibilities for activities in which they are competent. It is not always easy to refuse when there is no one else to carry out the tasks, especially if this means that clients’ needs will not be met, but the onus is placed on the individual by the code. The supervisor of midwives has to ensure that the rules and the code are honoured, and take action in the event of breach of any of them. Supervision should, through its development and use, enable practitioners to make a real contribution to any organization’s ability to manage risk effectively.

It is impossible to be a supervisor of midwives without practising risk management. Supervisors can ensure the best outcome for mother and baby by influencing how midwives practise. When supervision is carried out effectively, with a particular regard to the monitoring of midwives’ practice and competence, the perceptions of risk can be related to midwifery practice, as can the principles of risk management.

Supervision and management

These two entities are often confused and yet they are distinctly separate. This confusion is probably a legacy from the introduction of supervision of midwives into hospitals in 1974 when the midwifery managers became supervisors of midwives. To many midwives the positions appeared synonymous; indeed many of the supervisors themselves failed to distinguish between the two roles (RCM 1994). There are many more supervisors of midwives in clinical posts than in management, so the differences are much clearer to midwives today. Much work has been done in recent years to educate midwives, and supervisors of midwives, about the different roles and to increase awareness of the benefits of statutory supervision. There is now a trend for any midwifery managers who are also supervisors of midwives, not to supervise the midwives they manage.

There is no hierarchy within supervision; from the moment of appointment, supervisors of midwives have full supervisory responsibilities. They will be preceptored into their role by more experienced supervisors, but there is no seniority or ranking of supervisors.

There should not be any conflict between supervision and management as, when acting in either capacity, the objectives are clear and separately defined. The aims of supervision are to ensure the safety of mothers and babies and support midwives in order to achieve high standards of practice, while the aim of management is to achieve a high quality service to meet contract specifications and make the best use of resources. If there is a critical incident to be investigated, the same one person cannot act as both manager and supervisor, as the former is acting on behalf of the Trust and the latter as advocate for the midwife with responsibility to the LSA (Duerden 2000b). Despite this, confusion continues to exist, particularly considering suspension (Shennan 1996) and the difference between suspension from duty, a management procedure, and suspension from practice, a recommendation to the LSA by a supervisor of midwives.

To assist the reader, a list of responsibilities of a supervisor of midwives is given in Box 52.3.

Box 52.3 Responsibilities of a supervisor of midwives

Each supervisor of midwives

Clinical governance

Clinical governance was defined in First Class Service (DH 1998, p 33) as ‘a framework through which NHS organizations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish.’ This systematic approach to maintaining and improving the quality of patient care continues in the NHS. Since 1998 the Government has published a further three white papers on the reform of professional regulation and clinical governance: (DH 2007a,b,c).

Professional self-regulation and life-long learning are key themes within clinical governance and these have all been integral to the supervision of midwives for some time past. The philosophy for the supervision of midwives and the standards it develops thus reflect the key themes of clinical governance.

Supervision of midwives promotes and develops safe practice and ensures the dissemination of good, evidence-based practice and innovation (LSAMO & NMC 2008). Since 1955, supervision of midwives has ensured a statutory framework for continued professional development, and compulsory refreshment of midwifery knowledge has led to a life-long learning programme for midwives throughout their careers. Supervision has provided a formal focus of support and reflection with a confidential review of professional development needs. It is evident, therefore, that the supervision of midwives contributes to an effective framework of clinical governance, minimizing risk, reducing patient complaints, and contributing to a multidisciplinary collaboration in producing practice guidelines (ENB 1999).

The government has set clear national standards backed by consistent monitoring arrangements. The LSA Midwifery Officers, through their supervisory audit visits to each maternity unit, regularly monitor standards of practice against documented evidence such as that produced by the Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy (CESDI) and the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD). National standards are also developed through National Service Frameworks (NSF) and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). The implementation of the Maternity Standard of the NSF for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (DH 2004) can also be monitored in this way.

Where there are unacceptable variations in clinical midwifery practice, or care is inappropriate for women’s needs, the LSA Midwifery Officer, as an outside assessor, is in a position to recommend remedial action (Duerden 2000a). Similarly, the LSA can contribute to the dissemination of information from NICE to ensure the implementation of the most effective care.

The clinical governance framework

First Class Service (DH 1998) described a clinical governance framework (3.11) to:

All of these aspects of clinical governance are covered within the ambit of supervision of midwives. Supervisors of midwives monitor midwifery practice and they are able to discuss with midwives the regulation of midwifery practice and ensure full understanding of accountability to themselves, to the Nursing and Midwifery Council and to the Trust that employs them.

The principles of life-long learning are deep rooted in supervision with its history of regular refresher courses.

Systems for quality control, based on clinical standards, evidence-based practice and learning the lessons of poor performance, are met through supervisory audit. Evidence-based practice is a term which might be considered to be over- and inappropriately used, but it is crucial to the Government’s programme of quality improvement activities within clinical governance: ‘Evidence-based practice is supported and applied routinely in everyday practice’ (DH 1998, p 36). Supervisors of midwives have a responsibility to monitor midwifery practice. Not only must they ensure that the practice within their own clinical area is evidence-based, but they must also challenge areas of practice which are carried out, out of a sense of tradition, and without any evidence for maintaining them. They must also ensure that the midwives concerned understand not only the meaning of evidence-based practice, but that they also know where and how to find evidence and evaluate it adequately, being able to differentiate between poor and high quality studies.

Supervisors of midwives are in an excellent position to identify good practice and also to learn of examples of good practice in other maternity units which can be adopted within their own Trust, as such examples are shared through the supervisory network. Where midwives have ideas for changing and improving practice, supervisors of midwives should be able to empower the midwives to introduce such change and support them in their initiatives acting as their advocate with senior staff. A supervisor of midwives should be among the membership of every labour ward forum (RCOG-RCM 1999) providing a useful opportunity for the sharing of new ideas and encouraging midwives to attend in order to promulgate their suggestions for changing practice.

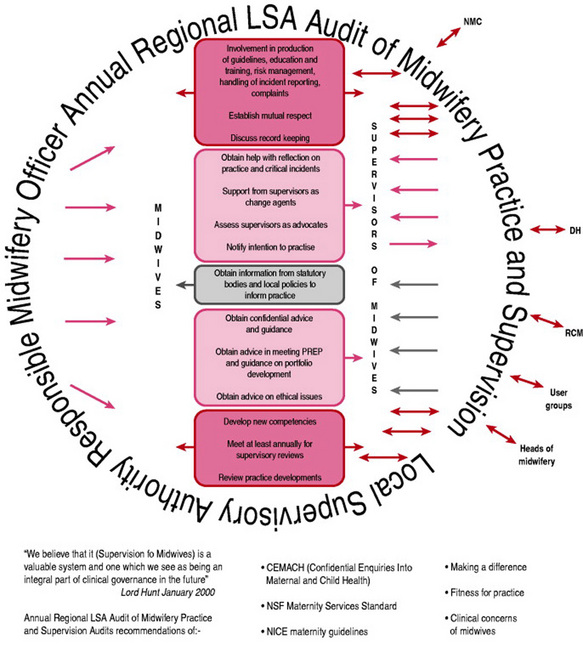

Through regular monitoring of midwifery practice, especially by supervisors of midwives who work in the clinical environment, areas of risk can be identified and addressed. Critical incident analysis is a crucial part of the supervisor’s role. Following any untoward event or ‘near miss’, some sort of incident form will be completed. All untoward events involving midwives are recorded, investigated and monitored by supervisors. An illustration of how the statutory supervision of midwives sits within clinical governance is shown in Figure 52.1.

Figure 52.1 The link between clinical governance and statutory supervision of midwives devised by supervisors.

(Original model devised by supervisors of midwives at Airedale Hospitals NHS Trust. Permission to reproduce from Carol Paeglis, when Practice Development Nurse/Midwife, Airedale Hospitals NHS Trust and Rachel Wilson, Medical Illustrator, Airedale Hospitals NHS Trust.)

Quality

Most hospitals have regular perinatal audit meetings, designed to review the outcomes of clinical care and identify possible areas for improvement. These are excellent arenas for supervisors of midwives to monitor midwifery practice and take appropriate action where suboptimal care has been demonstrated.

The results of research should inform our decisions about healthcare. It is, however, evident from the conclusions of Enkin et al (2000) that research findings appear often to be only slowly and incompletely reflected in practice. Many journals available to midwives provide a great deal of up-to-date information on research findings relevant to practice, but access to information alone does not always influence putting research findings into clinical practice. Research reports can also be from very small studies where the findings are not sufficiently significant or robust to put into general practice. Support and advocacy from a supervisor will often be necessary to make relevant changes to practice and to avoid implementing unsubstantiated practice.

Another body that, through the Government’s Modernization Programme, monitors quality and performance in Trusts is the Healthcare Commission. With the regular monitoring visit of the LSA responsible midwifery officer, plus a visit by the Healthcare Commission, it is understandable if midwifery staff can sometimes feel overwhelmed and over-inspected. In addition to these visits there will be visits from the Royal Colleges to assess the practice area for medical staff training. The NMC periodically assesses the practice area for the education and training of student midwives. This rigorous monitoring means that, from a clinical governance perspective, there can be confidence in the standard of care provided in each maternity unit.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is a government-appointed body which sets standards and guidelines for clinical practice in all specialities. There are now many sets of guidelines published by NICE which dictate practice for midwives and obstetricians and supervisors of midwives have a role here in ensuring that midwives implement these guidelines. The electronic fetal monitoring guidelines (NICE 2001) created problems for some midwives who felt insecure if they did not monitor every woman admitted in labour for at least 20min, and supervisors of midwives have had to support midwives through a change of practice which can enhance woman-centred care, rather than medicalizing a problem-free labour.

Policies, protocols and guidelines

Many maternity units will have protocols, policies and guidelines in place to govern the way in which care should be provided. These terms sometimes lead to confusion, and may be used interchangeably. The word protocol now has many different meanings in different professions, especially in information technology and mathematics. Within healthcare research it is an action plan for a clinical trial, but generally a protocol is a written system for managing care that should include a plan for audit of that care. Baillière’s Midwives’ Dictionary (Tiran 2007) describes a protocol as ‘protocol agreement between parties; multidisciplinary planned course of suggested action in relation to specific situations’. Protocols determine individual aspects of practice and should be researched using the latest evidence. Most protocols are binding on employees as they usually relate to the management of consumers with urgent, possibly life-threatening, conditions. A protocol may exist for the care of women with antepartum haemorrhage, but not for the care of women in labour without complication. If midwives work outwith a protocol they could be considered to be in breach of their employment contract.

Guidelines, or procedures, are usually less specific than protocols and may be described as suggestions for criteria or levels of performance that are provided to implement agreed standards.

Policies are general principles or directions, usually without the mandatory approach for addressing an issue, but might be considered mandatory in some Trusts. They are often set at national level, such as the Maternity Standard, National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (DH 2004).

It is essential that supervisors of midwives ensure that midwives clearly understand the different definitions.

Using supervision effectively

Partnership

To benefit from supervision, mutual respect between supervisors of midwives and midwives is essential. Midwives should work in partnership with their supervisors and make the most of supervision (LSAMO & NMC 2008), so that it can be effective for not only themselves but also for the mothers and babies for whom they care. When supported by a supervisor of midwives, a midwife can practise safely with confidence.

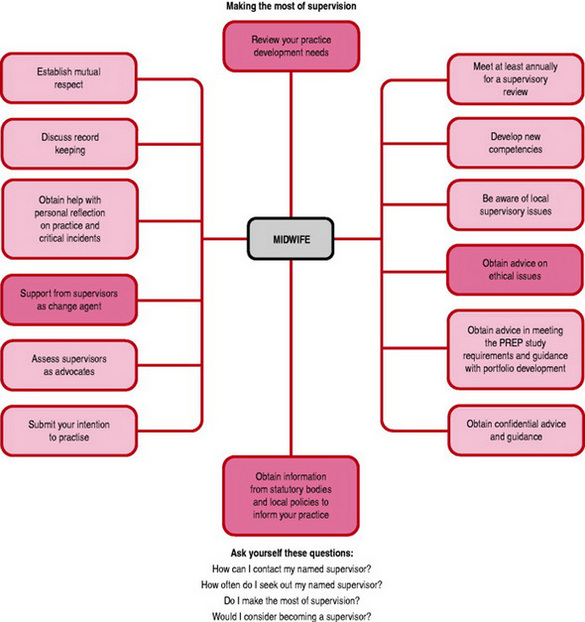

The primary responsibilities of a midwife are to ensure the safe and efficient care of mothers and babies; maintain personal fitness for practice and maintain registration with the NMC. The supervisory relationship enables, supports and empowers midwives to fulfil these responsibilities. In Figure 52.2 the reader can see how a midwife can make the most of the supervision and the benefits of a professional relationship with the named supervisor of midwives.

Figure 52.2 Making the most of supervision.

(From Supervision in Action ENB 1999, with permission from English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting.)

Accountability and advocacy

Accountability of midwives means that midwives are answerable for actions and omissions, regardless of advice or directions from another professional. There will be occasions when midwives have difficulty appreciating their own accountability, especially when carrying out the instructions of medical staff, but it is clear from the NMC Code (2008) that accountability cannot be either delegated to or borne by others; it simply rests with the practitioner. A registered midwife is accountable to the NMC as well as to the employing Trust. The dilemmas that this might create can be discussed with a supervisor of midwives for greater clarity and understanding.

When acting as advocates for women exercising their choice, which might not be in keeping with Trust policy, midwives may wish to seek the help of their supervisor or the supervisor of midwives on call. The supervisor can help by supporting midwives in caring for women, giving advice about documentation and even initiating a review of the policy in light of new evidence.

Just as Trust policies can inhibit a woman’s choice, so can the availability of services. Examples of this are home births and water births. Women may demand either of these services when the Trust either cannot or does not provide them. Home birth services are occasionally temporarily withdrawn during staffing crises, and some Trusts will not support women giving birth in water. Women will sometimes opt for a home birth when their obstetric history would place them outwith the criteria. Situations such as these will challenge a midwife’s responsibilities both as a midwife and as an employee. This is another useful time to seek out the support of a supervisor of midwives to talk through the issues.

Choice

Midwives are able to choose their supervisor of midwives, usually from a list provided by the contact supervisor. A midwife should consider carefully with which supervisors an open and honest relationship could be formed and whether or not there would be mutual respect. The supervisor should also be able to appreciate the environment in which the midwife is currently practising.

Midwives prioritized the qualities required in a supervisor during an audit of supervision (Duerden 2000b). The results in priority order were: approachable; clinically experienced; in touch and up-to-date; willing to take action; a good listener; a good role model; a good advocate; wise; empathetic and sympathetic. In Modern Supervision in Action (LSAMO & NMC 2008, p9) the qualities of a supervisor of midwives are listed as approachable; committed to woman-centred care; a source of professional knowledge and expertise; visionary and inspiring; able to resolve conflict; motivated and thorough; articulate trustworthy; sympathetic and encouraging; and, finally, fair and equitable. These lists make a supervisor of midwives sound like the perfect being, but realistically it is impossible for one person to have all these qualities. It is, however, important for a midwife to judge which qualities are important in a supervisor of midwives and to consider the qualities of each supervisor on the proffered list.

The ability to maintain confidentiality is not listed among the qualities described above, but it is implicit in the role of the supervisor of midwives. A midwife must feel confident at all times that discussions with a supervisor of midwives will remain confidential. There will always be times when the supervisor of midwives may need to take action in the interest of safety, in which case discussion would take place about the need to share the information. Similarly, the midwife might be encouraged to take the initiative to raise the issue with the midwifery manager.

Support

In the modern NHS, change occurs at an alarming rate. This can be very stressful for midwives, especially if it means a change in practice or the work area. The supervisor of midwives is well placed to advise and guide midwives who are challenged by change and any concerns that a midwife might have, should be shared with the named supervisor. Similarly, the supervisor can act as advocate for the midwife in debate among professional groups, especially if the practice being suggested is not evidence-based. At all times, the supervisor of midwives’ responsibility is to protect the public and ensure the highest standards of care and professional practice by midwives.

Supervisory reviews

The annual supervisory review should be used by midwives to reflect on their midwifery practice in a confidential arena where aspirations and goals for the future can be shared. Both midwife and supervisor should value the meeting, as this is the opportunity to take time out and consider personal learning needs and professional development requirements in order to achieve goals. Midwives are responsible for meeting their own PREP requirements before re-registering with the NMC (NMC 2006b) and these requirements can be discussed with the supervisor of midwives during the review. The supervisor will probably have information about the Trust professional development budget and will be able to guide the midwife if further academic study is being considered.

This secure environment should provide an opportunity to evaluate practice, and share any practice issues causing concern. If it is felt necessary, the supervisor will investigate the matter in confidence and take appropriate action. If a midwife feels that, because of allocation to one practice environment for a protracted time, midwifery skills are being lost, the supervisory review can be used to consider mechanisms for gaining relevant experience in other areas and receiving the necessary professional update.

A midwife may have a particular interest in research or audit. Using the supervisor of midwives as a sounding board can assist greatly in making decisions, and guidance can be obtained.

There cannot always be a perfect supervisory relationship, but to get the most out of supervision the relationship must have the essential elements of mutual respect and confidentiality. Research (Stapleton et al 1998) clearly demonstrated that midwives who feel empowered by their supervisor of midwives feel able to empower their clients. Being valued and supported by supervisors and having achievements recognized will enhance professional confidence and practice. The supervisory decisions perceived as empowering are those made by consensus between the supervisor and the midwife (Stapleton et al 1998). If this relationship is not recognized by either midwife or supervisor, then the opportunity to change supervisor should be taken by the midwife, possibly with the encouragement of the supervisor of midwives who will know that there can be no success without the necessary rapport and confidence in the supervisory relationship. It benefits some midwives to change their supervisor every few years, while others feel the need for a longer-term relationship.

An over-secure relationship should also be avoided as the supervisor is not there to attend to the midwife’s every need. At all costs, dependency should be avoided. Midwives are accountable for their own practice and continuous professional development. They should not be seeking out their supervisors all the time, but should recognize that all supervisors of midwives have substantive posts to which supervision is an addendum. For many, this means that much of supervision is carried out in personal time, so demands made on the supervisor should be considered, and arrangements made to meet at mutually convenient times. When the named supervisor of midwives is not available, there is always an on-call supervisor to deal with emergencies. A helpful list of ways to get the best from supervision is provided at Box 52.4.

Box 52.4 Getting the best from supervision

Conclusion

With the support of supervisors of midwives, midwives can expect to practise confidently and competently, but they must value supervision in order to gain its maximum benefit and to receive the empowerment it can provide. The changing role of the midwife, described in this book, highlights the need for support through the change programme.

DH (Department of Health). First Class Service. London: HMSO, 1998.

DH (Department of Health). Making a difference: strengthening the nursing, midwifery and health visiting contribution to health and healthcare. London: HMSO, 1999.

DH (Department of Health). Shifting the balance of power: launch of the NHS modernization agency speech by Secretary of State, 2001.

DH (Department of Health). Establishing the new Nursing and Midwifery Council, April. London: DH, 2001.

DH (Department of Health). Making a Difference the nursing, midwifery and health visiting contribution. The Midwifery Action Plan. London: DH, 2001.

DH (Department of Health). Maternity standard, national service framework for children, young people and maternity services. London: DH, 2004.

DH (Department of Health). Trust, assurance and safety: the regulation of health professionals in the 21st century. 2007. Online. Available http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/14/31/43/04143143.pdf.

DH (Department of Health). Safeguarding patients. 2007. Online. Available http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/14/32/48/04143248.pdf.

DH (Department of Health). Learning from tragedy: keeping patients safe. 2007. Online. Available http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/14/32/49/04143249.pdf.

Duerden JM. The new LSA arrangements in practice. In: Kirkham M, editor. Developments in the supervision of midwives. Hale: Books for Midwives, 2000.

Duerden JM. Audit of supervision of midwives. In: Kirkham M, editor. Developments in the supervision of midwives. Hale: Books for Midwives, 2000.

ENB (English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting). Preparation of supervisors of midwives: an open learning programme. London: ENB, 1992.

ENB (English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting). Advice and guidance to local supervising authorities and supervisors of midwives. London: ENB, 1999.

Enkin M, Keirse M, editors. Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth, 3rd edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Kirkham M. The history of midwifery supervision. Supervision Consensus Conference Proceedings. Hale: Books for Midwives, 1995.

LSA Midwifery Officers National (UK) Forum & Nursing and Midwifery Council. Modern Supervision in Action - a practical guide for midwives. London: NMC, 2008.

MoH (Ministry of Health). Circular 1620 Supervision of midwives. London: MoH, 1937.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). Electronic fetal monitoring: The use and interpretation of cardiotocography in intrapartum fetal surveillance. London: NICE, 2001.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Preparation of supervisors of midwives. London: NMC, 2002.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Midwives rules and standards. London: NMC, 2004.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Guidelines for records and record keeping. London: NMC, 2005.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Standards for the preparation and practice of supervisors of midwives. London: NMC, 2006.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). The PREP handbook. London: NMC, 2006.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). The NMC Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. London: NMC, 2008.

RCM (Royal College of Midwives). Supervision of midwives and midwifery. Practice Paper 6: Future practices of midwifery. London: RCM, 1994.

RCOG/RCM (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Royal College of Midwives). Towards safer childbirth minimum standards for the organization of labour wards. London: RCOG, 1999.

Shennan C. Midwives’ perception of the role of a supervisor of midwives. In: Kirkham M, editor. Supervision of midwives. Hale: Books for Midwives, 1996.

Stapleton H, Duerden J, Kirkham M. Evaluation of the impact of the supervision of midwives on professional practice and the quality of midwifery care. London: English National Board, 1998.

The Nursing and Midwifery Order. (Transitional Provisions) Order of Council 2004 (SI 2004/1762), 2001.

Tiran D. Midwives’ dictionary, 11th edn. London: Baillière Tindall, 2007.

UKCC (United Kingdom Central Council For Nursing Midwifery and Health Visiting). Midwives rules. London: UKCC, 1993.

UKCC (United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing Midwifery and Health Visiting). Midwives code of practice. London: UKCC, 1994.

UKCC (United Kingdom Central Council For Nursing Midwifery and Health Visiting). Midwives Refresher Courses and PREP. London: UKCC, 1997.

UKCC (United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing Midwifery and Health Visiting). Midwives rules and code of practice. London: UKCC, 1998.

LSA Midwifery Officers National (UK) Forum & Nursing and Midwifery Council. Modern Supervision in Action - a practical guide for midwives. London: NMC, 2008.

This useful little book helps midwives to get the most out of supervision. It is very user friendly and explains the supervision of midwives very succinctly from the perspective of the midwife rather than the supervisor of midwives.

Kirkham M, editor. Supervision of Midwives. Hale: Books for Midwives, 1996.

This book contains a comprehensive examination of the supervision of midwives beginning with a fascinating history of supervision and also giving some examples of good practice within supervision.

Kirkham M, editor. Developments in the supervision of midwives. Hale: Books for Midwives, 2000.

Following on from the previous book, this edition explores how the supervision of midwives has developed in recent years, describing research and audit of supervision, changes in practice and education and training for supervisors of midwives