Chapter 53 Risk management in midwifery

Midwives work in an environment that entails risks to mothers, to babies, to their employer and to themselves. They must understand the basic principles of risk management and how it applies specifically to their practice.

Although its original application in healthcare lay in an attempt to reduce litigation, risk management is now seen by most practitioners and NHS Trusts as a vehicle for enhancing the quality of client care as part of modern clinical governance.

Introduction

The various meanings of ‘risk management’

In the context of healthcare in general and midwifery in particular, the term ‘risk management’ can be used in a number of senses.

In this chapter, risk management will be examined both as a broad philosophy and in the more restrictive sense in which it is sometimes used in the NHS. As will be seen, these two approaches are rapidly converging – or, more correctly, the narrower approach is largely giving way to the broader approach. The practice of care in the NHS is becoming much more client/patient orientated. Furthermore, it is becoming clearer to clinicians and litigation-funders alike that the best way to achieve the goals of the Health Service as a whole and, at the same time, to reduce litigation risk is to use the available resources to provide the best possible service to the client – risk management should be used positively to deliver that service rather than seeking primarily to counter the threat of litigation.

Risk and the midwife

In the publication ‘Engaging Clinicians’, the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) (2005) puts risk management at the heart of the process of ensuring patient safety:

Everyone who works in the NHS contributes to the systems which deliver healthcare … Patient safety is therefore everybody’s business. The process by which an organisation makes patient care safer should involve:

While childbirth is reasonably safe in the developed world, there are aspects which demand proper risk management. Risk in maternity is getting ever greater attention; for example, the Healthcare Commission (HCC), the watchdog on delivery of NHS services and NPSA jointly held a conference entitled ‘Safe Delivery – Reducing Risk in Maternity Services’. At the conference, Lord Patel, Chairman of the NPSA, identified what he described as a new paradigm in healthcare:

The identification, analysis and management of patient-related risks and incidents in order to make patient care safer and to reduce harm.

The standard Maternity Care Pathway set out in Maternity Matters (DH 2007) describes the first key activity as a ‘standardized risk and needs assessment’. Midwives will be called on to weigh risks at all stages of the process, for example in discussing with women whether provisional pathway choices need to be reconsidered – a woman who has provisionally opted to have a home birth may need to review this in the light of later information, e.g. detection of raised blood pressure, and it will fall to the midwife to discuss the risks with the woman.

While supervisors of midwives are required to promote childbirth as a normal, physiological event they must also ‘demonstrate the ability to undertake assessments of practice to identify potential/actual risks and mitigate where possible’ (NMC 2006).

It is essential that midwives take their responsibilities in respect of risk seriously, but midwives must interpret these responsibilities within their own professional context. Although childbirth is a relatively safe and natural process, a number of factors have, in recent years, amplified the perceived risks:

Midwives must use risk management responsibly. In particular, midwives must be aware that the terminology of risk can be disempowering. Women may see themselves no longer as independent actors but as reliant on ‘medical’ professionals to steer them safely through a dangerous condition. Thomas (1998) advises midwives:

… to use risk management as a tool in the planning and provision of safe systems of care, while at the same time supporting the view that pregnancy and birth is a safe process for the majority. To do this the midwife will need to understand the risks, using the evidence as it becomes available, and to put those risks into proper perspective. This will enable the midwife to explain risks to the mother in a way that allows constructive debate and decision making without creating anxiety, which in itself can lead to unnecessary intervention.

A brief historical review of risk management in midwifery

The original view of risk management: a response to litigation risk

The NHS pays out almost £600 million annually in litigation costs (NHSLA 2006). Some 30% of this vast cost to the NHS arises from midwifery/obstetric work although this proportion is difficult to assess because obstetric-related claims tend to be delayed. Analysis also shows (DH 2000) that the vast majority of mistakes – probably >75% – are caused by ‘systems failures’. This means that no one individual can be said to have caused the incident. The real cause of the mistake was a failure of one or more of the following: communication, supervision, checking, staffing levels, equipment, etc.

As a result of such statistics, it was clearly seen that the most significant improvement in healthcare outcomes could be produced not by new medicines or treatments, but by tightening up on the management of the system, particularly in midwifery and maternity departments.

Those who developed the early ideas were clinical negligence lawyers and medical practitioners with experience of reviewing legal claims. A consequence of this was that ‘risk management’ was seen in these early days almost entirely in terms of minimizing litigation risk. For example, Clements (1995) suggested: ‘Risk management is the reduction of harm to the organisation, by the identification and as far as possible elimination of risk’. Dineen (1997) explicitly links ‘risk management’ with clinical negligence litigation.

The development of a broader view of risk management: enhancement of client care

Many people – both policy-makers and employees of the NHS – were uneasy about risk management which was designed to protect the ‘organization’ (i.e. the Hospital) against the ‘patient’. As a consequence, an alternative approach to risk management developed – the ‘enhancement of client care’ model. Aslam (1999, p 42), for example, says: ‘enhancement of client care, rather than litigation avoidance, should be the principal driving force in implementing risk management procedures’. This alternative approach places little direct emphasis on saving the hospital from litigation; rather, it takes as its starting point the provision of a quality service in the interests of all parties, but especially mothers and babies. It involves balancing risks against opportunities in clinical decisions so that – like an airline company – it provides a safe, satisfying and convenient service.

This latter approach is now broadly supported by the professional institutions as well as the Government. For example, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG 2005) advise that risk management should promote reflective practice and be used to improve subsequent care.

The more common use of the term ‘risk management’ in its wider sense does not mean that the use of the term to describe processes that are exclusively aimed at reducing litigation risk has disappeared. Indeed, it will not disappear because Trusts must, of course, take reasonable precautions to safeguard themselves from spurious litigation; and they have an obligation to ensure that funds are used for the benefit of all.

The clinical negligence scheme for Trusts

One of the most significant changes in the structure of the NHS took place in the early 1990s with the establishment of NHS Trusts. The legislation that established the Trusts also required them to meet the considerable litigation costs. In order to manage this most effectively, a system of pooled insurance – known as the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST) – was established in 1994 and came into effect in 1995/6. It is administered by a special health authority, the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA).

Although membership of the CNST is optional, the vast majority of Trusts did in fact join and so the CNST requirements were, in essence, requirements placed on all Trusts. These requirements were published as standards that participating Trusts are required to meet. The standards were expressed in terms of processes, most of which clearly fell within the general realm of ‘risk management’. Thus, risk management was no longer an optional extra for Trusts striving for excellence, but was now a core activity. Indeed, because discounts on the insurance premiums are available for improved compliance with the standards (level 1 is the basic requirement for cover, 2 is good and 3 is the top level of attainment), risk management has become an activity with significant funding implications.

The CNST publishes a general set of standards for Trusts and also a special standard for maternity services as maternity claims account for a significant proportion of those reported to the NHSLA (2007).

The CNST standards for maternity services are contained in eight categories: organization, learning from experience, communication, clinical care, induction, training and competence, health records, implementation of clinical risk management and staffing levels.

The modern context of risk management: a strand within clinical governance

The Government has actively promoted a view of risk management that begins to resemble that used in many other industries: risk management as part of the overall provision of a quality, customer-focused service.

As a result of the Health Act 1999, Trusts are obliged to implement, maintain and improve quality. This is achieved under the banner of clinical governance, the essential features of this are the integration of all those processes that improve client care, including improving clinical quality by building on good practice, development of clinical risk reduction programmes, the promotion of evidence-based practice and the detection and open investigation of adverse incidence and near misses.

The formal system of clinical governance places a responsibility on all to have the appropriate systems in place and to ensure that such systems are effective. However, even prior to the introduction of the current system of clinical governance, midwifery already had systems that operated in that spirit. These include statutory supervision, the setting of standards, evidence-based policies and protocols and research and audit. The professional institutions have all welcomed clinical governance. The Royal College of Midwives’ paper, Assessing and managing risk in midwifery practice (RCM 2000) says, for example: ‘Clinical governance is to be integrated with risk management to raise standards of care. The fundamental aims of this process are to raise standards of care and define best practice, thereby improving quality outcomes. It also has the potential to reduce medical negligence claims’.

The risk management process

A generic model

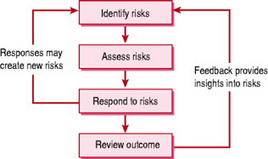

Many of the principles of risk management are generic; the basic principles apply equally to operating a passenger airline as they do to midwifery. Risk management is often described using a ‘process model’ such as that shown in Figure 53.1. This model can be described as follows.

Identifying risks

Risks are those factors that may affect our prospects of achieving an optimal result. The types of question that need to be asked are: ‘what could go wrong?’, ‘what are the chances of it going wrong and what would be the impact?’, ‘what can we do to minimize the chance of this happening or to mitigate damage when it has gone wrong?’ and ‘what can we learn from things that have gone wrong?’ (RCOG 2005, section 3.2). Personal experience is a relatively uncertain form of data acquisition, despite reflective practice models (e.g. Clements 2000). More reliable will be incident reporting and Confidential Enquiry reports (e.g. Lewis 2007).

Assess risks

Those factors that generate the greatest risk need to be assessed in order to gain some indication of how high those risks are. The risk of an outcome is generally considered to be the product of the probability of that outcome multiplied by the severity of that outcome if it were to occur. Thus, life-threatening outcomes must be kept at very low levels of probability to be acceptable, whereas outcomes such as vaginal/perineal lacerations and short term discomforts may be tolerated at much higher levels of probability.

Respond to risks

In the most dangerous situations, such as a compromised fetus, risk response may be dramatic – for instance by opting for an emergency caesarean section. In less risky situations, monitoring may be required. Responses must be guided by the need to minimize the risks without sacrificing the aspirations of the client; for example, if a client expresses a sincere desire to have a natural childbirth, the midwife should refer to the possibility of medical intervention only when this is becoming increasingly advisable.

Review outcome

As part of an ongoing commitment to improving service, performance is reviewed in order to improve the service provided.

There are two ‘feedback loops’ in the model. The first (emanating from ‘respond to risks’) requires the midwife to identify whether the response to existing risk itself has created any new risks. For example, if a drug is administered to control one problem, it may have side-effects, which also need to be risk managed. The second feedback loop involves an input from experience into the way that the individual and team as a whole identify, assess and respond to risks for future clients.

Reactive and proactive risk management

Reactive risk management involves learning from one’s mistakes. However, the generic model presented in Figure 53.1 encourages a more proactive approach. The aim is to identify and manage risks before they occur so as to avoid harm rather than to learn from it. It is sometimes said that proactive risk management helps us to learn from our mistakes without having to make them.

Of course, all midwives should aspire to proactive risk management by continually striving to develop new and better forms of care, subjecting each to a rigorous risk assessment before implementation. But it is necessary also to be realistic and to recognize that many risk factors are well understood only after having caused adverse outcomes. In practice historical data are relied upon to identify, assess and respond to risk. But it is essential always to be alert to identify new risks and to manage them before they become unfortunate statistics.

Guidelines and protocols

Although the generic model applies to every situation, and although proactive risk management is desirable, it is nevertheless unrealistic and indeed inappropriate for each midwife (or other health professional) to consider the application of the generic model in each and every clinical situation. Not only is there not usually enough time to carry out detailed individual assessments in most routine cases, but the individual carer is unlikely to have a sufficient in-depth knowledge of the relevant data to enable them to make full assessments. Therefore, in order to assist carers in their choice of care, guidelines are developed for day-to-day use. These provide a much more efficient and effective way of ensuring that staff act in line with acceptable evidence-based practice.

Guidelines are now drawn up in most maternity units for most critical or common conditions. For those Trusts subscribing to CNST, guidelines are mandatory. The CNST standards for maternity services (NHSLA 2007) require that:

4.1.1 There are referenced, evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines/pathways of care, for the management of all key conditions or situations on the labour ward. These are prominently placed in all ward areas

Some aspects of practical risk management

Identifying risks in a clinical setting

Risks occur in many forms. Table 53.1 sets out one way of classifying these risks.

Table 53.1 Classification of sources of maternity service risks

| Class of risk | Specific examples |

|---|---|

| Pre-assessable Medical, obstetric or social complications | Diabetes |

| Obesity (BMI 30 kg/m2 or above | |

| Hypertension, cardiac disease | |

| Smoking, alcohol or drug abuse | |

| Maternal age (≥40, teenagers) | |

| Breech presentation | |

| Psychiatric disorders | |

| Client choice risks | Home birth when risk factors |

| Elective caesarean | |

| Refusal or acceptance of interventions | |

| Systems failures | Ineffective communications |

| Inadequate training for emergencies | |

| Faulty or ineffective equipment | |

| Poor or inappropriate staffing | |

| Professional Misinterpretation risks | Mis-diagnosis |

| Inappropriate response – insufficiently rapid, or without checking | |

| Emergency situations | Shoulder dystocia |

| Maternal haemorrhage |

Risks arising from medical, obstetric, social conditions, client choices and professional misinterpretation are covered in other chapters. This chapter explores ‘systems failures’. Box 53.1 gives an example of a problem arising which cannot be ascribed to the failure of any specific individual. It may, in reality, be that almost all situations can be seen as part of a systems failure if for example skills drills for potential emergency situations are not regularly practised.

Box 53.1 Systems failures in maternity care

(Adapted from NPSA Case Histories No. 4, 2005)

General management and staffing

Following unexpectedly high rates of maternal deaths (10 deaths in 3 years) at an NHS Trust, ‘Special Measures’ were imposed by the Secretary of State. The structure of the unit was visibly altered with clinical leadership becoming more visible and supported by senior Trust staff. Staffing levels were raised generally to the levels in other similar hospitals and consultant obstetrician presence was raised by 50%. Revised protocols and guidelines were issued, coupled with better risk management processes, audits and multidisciplinary learning. Following marked improvements, ‘Special Measures’ were lifted in 2006. The Healthcare Commission report in August 2006 identified the following issues: ‘difficult decisions often left to junior staff … failure in a number of cases to recognize and respond quickly where a woman’s condition changed unexpectedly … inadequate resources to deal with high risk cases … failure to learn lessons on the unit … failure by the Trust’s Board to appreciate the seriousness of the situation’.

Risk management is not just for ‘risk managers’, but for everyone. The following principles may assist in correctly identifying and managing risks in practice.

Involving women in decision-making

The central importance of women’s informed choice is consistently underlined by all recent government policies, including Maternity Matters (DH 2007).

An example which raises difficult questions when midwives are faced with seeking to offer women their preferred pathway, but at the same time to promote childbirth as a natural and reasonably safe process, is the question of caesarean delivery. For example, NICE Clinical Guidance 13 (NICE 2004) speaks in terms of risk: ‘When considering a caesarean section (CS), there should be discussion on the benefits and risks of CS compared with vaginal birth specific to the woman and her pregnancy’.

Identifying risks at an early stage

This is emphasized by Maternity Matters (DH 2007) which proposes a standardized ‘risks and needs assessment’ as the first stage of maternity care. This will essentially build on the system in place at present for carrying out:

Dealing with risks when they arise

(see Box 53.2) This includes:

J. was an experienced midwife and worked part-time, usually on the wards. She was allocated to work on the labour ward for a nightshift and was caring for Mrs W., who was in labour following induction for suspected intrauterine growth restriction and raised blood pressure. When she took over the care, the on-call medical team had made an assessment as part of the routine labour ward round and there were no concerns about fetal or maternal well-being. There was no specific plan in the clinical notes. An epidural was in place and Syntocinon was being used to stimulate uterine activity. Midwife J. knew that continuous monitoring was required, in accordance with the unit protocol.

Midwife J. was finding it difficult to keep her records up-to-date as she was not used to caring for a woman with an epidural and Syntocinon and was kept very busy giving care and support to Mrs W. and assessing fetal and maternal condition. Over time, a pattern of shallow decelerations were seen on the trace and midwife J. was aware of this and noted it in the clinical records. She was able to assess that these were early/variable and therefore consistent with cord compression and advancement of labour. Midwife J. considered that this may be a sign of the onset of the second stage. The baseline rate of the fetal heart rose from 130 b.p.m. to 155 b.p.m. and midwife J. was not concerned, as she was aware that the normal fetal heart rate should be within the range of 110–160 b.p.m. When the variability reduced to below 5 b.p.m. midwife J. was not concerned, as she was aware that it needed to be reduced for a period of more than 40 min for there to be any concern.

Several hours after the shift started, the coordinator sent midwife B. to relieve midwife J. for a break. On entering the room, midwife B. observed that the CTG trace showed evidence of late decelerations, almost absent variability and a baseline rate at the top of the normal range. The coordinator was informed and medical assessment led to a fetal blood sampling. The result indicated significant fetal acidosis and an emergency caesarean section was performed. The baby was born in poor condition and required some resuscitation and transfer to the neonatal unit. The baby subsequently developed cerebral palsy. As the antenatal and early labour CTGs had been reassuring and there was evidence of slowly developing fetal heart rate abnormalities during several hours of labour, it was concluded that the damage to the baby probably occurred during labour.

Midwife J. was very upset, as she considered that she was totally responsible for the events and the outcome.

Issues

Education: The Unit had a system in place that ensured that all staff received yearly training and updating in CTG interpretation. Midwife J. had attended a session 9 months earlier. She had not cared for a woman in labour with a CTG since the day of training, as her only allocation to the labour ward had been to care for low-risk women who required intermittent monitoring.

Allocation: There was no attempt to ascertain whether midwife J. felt competent to care for a high risk woman in labour.

Midwife J. felt anxious about the allocation as she had not worked on the labour ward for some time but felt unable to communicate this to the coordinator, as the Unit was busy and as an experienced midwife, she was expected to be able to perform a full range of duties.

The coordinator was aware that midwife J. was not frequently allocated to the labour ward but was aware that she was an experienced midwife.

The coordinator was aware that there had been changes on the CTG trace as midwife J. had informed her that there had been some decelerations. She did not think it appropriate to assess the CTG for herself as midwife J. was an experienced midwife and should not require supervision.

Through the risk management system, another case had been identified in the previous year, whereby midwife J. had failed to inform the medical staff of a fetal bradycardia until it had been in progress for 6 min. In that case, an emergency caesarean section had been performed and the baby had been born in good condition. As there was no adverse outcome, no support or education was provided and no further action was taken. The coordinator was not aware that there had been concerns about midwife J.’s ability to interpret CTG traces in the past.

Findings and recommendations

There were several system failures:

Recommendations

Evidence-based practice and communication

It is important that decisions concerning the management of an individual woman’s care are made with their full and informed consent (except, of course, in unavoidable emergencies). This frequently means that the risks must be fully and clearly explained to her. For example, if the woman’s inclination is to have a totally natural childbirth, but the fetus is in a breech presentation, the risks and contingency plans need to be explained in a way that:

Clearly this not only involves good communications skills, but also requires that the midwife must fully understand the risks before attempting to communicate them to the client. Understanding of risks requires the midwife continually to update herself and to take a critical interest in research as published to ensure that the information being given is up to date, balanced and appropriate to the context.

The midwife needs also to be able to put risk data into perspective for the woman. For example if, following screening, the risk of the baby having a particular condition is ‘1 in 200’, some women may consider this a remote risk, whereas others may consider it a high risk. Some clients may wish to have a second, more invasive test, which carries a new risk of damaging the fetus and that new risk may also be expressed as a probability, say ‘1 in 50’. It is difficult for many people to comprehend these probabilities, and to decide what to do. The problem becomes even more acute when the woman is in a state of emotional shock; significant communication skills are required by the midwife to ensure not only that the risk data are presented but that their significance is fully understood.

Untoward incidents: reporting and staff issues

Reporting of untoward incidents

Reporting of untoward incidents is a key part of the risk management process and forms part of the drive to create organizations with a memory and reflective practice (DH 2000). The National Patient Safety Agency was established to develop a national framework for reporting incidents in a no-blame setting; it has set out ‘Seven Steps to Patient Safety’ (NPSA 2004), which supports blame-free reporting as part of an integrated risk management process. Reporting of incidents also forms an essential element of the CNST standards (see below).

The reporting framework

Effective management requires feedback on performance and, over recent decades, most maternity units have operated reporting systems – with a greater or lesser degree of formality. CNST ‘standard 2: Learning from experience’ (NHSLA 2007) sets out the requirements of a reporting system:

2.1.1 Adverse incidents and near misses are reported in all areas of the maternity service by all staff groups

2.1.2 Summarised adverse incident reports are provided regularly to the maternity services risk management group (or equivalent) for review and action

Incident report forms

Incident reporting forms have developed considerably over recent years. Added impetus comes from the requirements of CNST and Building a safer NHS for patients. Most Trusts have come to the view that a single Trust-wide form is appropriate, not least because it creates a sense of a common interest in reducing risk. Features of incident report forms include:

There is a growing body of literature on the analysis of incident report forms to which reference may be made (e.g. Vincent et al 2002).

Incident reporting: concerns of midwives

Risk management procedures such as adverse event and near-miss reporting may cause concern to staff, including midwives. Some may see it as a means for fostering rivalry and distrust among staff. However, the Government guidance has been at pains to promote a blame-free approach to reporting.

Adverse incident reporting is, first and foremost, a device for learning about the system and seeking to prevent systems failures. For example, Building a safer NHS (DH 2001) quotes Saul Weingart who says: ‘Improvement strategies that punish individual clinicians are misguided and do not work. Fixing the dysfunctional system, on the other hand, is the work that needs to be done’. Many Trusts are now seeking actively to allay the concerns of staff members about the effect of reporting an adverse incident in which they have been involved.

Nevertheless, no Trust can say categorically that no action will be taken. That is simply unrealistic – indeed, a Trust Chief Executive’s legal obligation (as part of his or her general clinical governance obligations) is to have appropriate procedures in place for dealing with staff whose performance needs correction.

Disciplinary action should not result from a report of an adverse incident, except in one or more of the following cases:

Conclusion

Midwives have traditionally seen childbirth as a reasonably safe and natural process. The advent of risk terminology and widespread screening has thrown the issue of risk into sharper focus. Risk is now a key factor to be considered in midwifery practice.

Risk management was first introduced into the NHS as a device for reducing litigation risk. The emphasis has changed over the past decade and the term ‘risk management’ is now largely used to mean risk reduction processes for the enhancement of client care.

The CNST was formed in the mid-1990s as a funding body for clinical negligence. Most Trusts have joined the CNST. They must therefore abide by the CNST standards, which contain detailed rules about the risk management processes that the Trust must operate. Maternity services are unique in having their own set of standards.

One of the most visible areas of risk management is that of ‘incident reporting’. In this chapter, we have examined some of the requirements laid down by the CNST and the involvement of central government through the National Patient Safety Authority. ‘Reporting’ is to be done within a culture that focuses on improving the system rather than blaming the individual.

The precise direction risk management will take in the future is somewhat uncertain. One thing that is certain, however, is that risk management will continue to play an important role in delivering a quality health service and that midwives will continue to play a key role in managing risk to provide enhanced client care.

Aslam R. Risk management in midwifery practice. British Journal of Midwifery. 1999;7(1):41-44.

Clements C. Critical incident analysis of the third stage of labour. British Journal of Midwifery. 2000;8(8):500-504.

Clements RV. Essentials of clinical risk management. In: Vincent C, editor. Clinical risk management. London: BMJ publishing Group; 1995:335-349.

Dineen M. Clinical risk management and midwives. Modern Midwife. 1997;7(11):9-13.

DH (Department of Health). An organisation with a memory. London: HMSO, 2000.

DH (Department of Health). Building a safer NHS for patients. London: HMSO, 2001.

DH (Department of Health). Maternity Matters: Choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service. London: DH, 2007.

Health Act. HMSO, London, 1999.

Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The seventh report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH, 2007.

NHSLA (NHS Litigation Authority). Report and accounts. London: NHSLA, 2006.

NHSLA (NHS Litigation Authority). Clinical negligence scheme for Trusts: clinical risk management standards for maternity services. London: NHS Litigation Authority, 2007.

NICE (National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence). Caesarean sections. London: NICE, 2004. Clinical Guideline 13

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Standards for the preparation and practice of supervisors of midwives. London: NMC, 2006.

NPSA (National Patient Safety Agency). Seven steps to patient safety. London: NPSA, 2004.

NPSA (National Patient Safety Agency). Engaging clinicians. London: NPSA, 2005.

Patel Lord Narem. Making maternity care safer. Presentation at the joint Healthcare Commission and NPSA Conference. Safe Delivery: Reducing Risk in Maternity Services, 26 June, London, 2007.

RCM (Royal College of Midwives). Assessing and managing risk in midwifery practice (RCM clinical risk management paper). RCM Midwives Journal. 2000;7:224-225.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology). Clinical risk management for obstetrics and gynaecology clinical governance advice No. 2, 2005.

Thomas BG. The disempowering concept of risk. Practising Midwife. 1998;1(12):18-21.

Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Chapman J, et al. How to investigate and analyse clinical incidents. British Medical Journal. 2002;320:771-781.

Clements RV. Risk management and litigation in obstetrics and gynaecology. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press in association with the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2001. (with specialist contributors)

A comprehensive review of risk management in its narrower sense of being specifically related to litigation risk. The first section focuses on the law, and considers the duties of the obstetrician, with respect to liability and causation in clinical negligence claims. The second section considers the principles of clinical risk management and includes an analysis of adverse outcomes, the basic principles of risk management, and how they relate to obstetrics and gynaecology. In the third and fourth sections, a variety of specialist clinical topics are dealt with.

Symon A. Risk and choice in maternity care: an international perspective. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

This book explores the relationship between risk and choice in maternity care. It contains a collaboration that sheds an international perspective with chapters on maternity care in the UK, USA, Australia and Ireland contributed by midwives, obstetricians, risk management experts and sociologists. The aim of this book is to illustrate the changing reality of risk management as it relates to maternity care, and to highlight risk management concerns that may limit the choices available to pregnant women.

Healthcare Commission: www.healthcarecommission.org.uk

National Health Service Litigation Authority: www.nhsla.com

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: www.nice.org.uk

National Patient Safety Agency: www.npsa.nhs.uk