CHAPTER 14 Preparation of Abutment Teeth

After surgery, periodontal treatment, endodontic treatment, and tissue conditioning of the arch involved, the abutment teeth may be prepared to provide support, stabilization, reciprocation, and retention for the removable partial denture. Rarely, if ever, is the situation encountered in which alterations of the abutment are not indicated because teeth do not develop with guiding planes, rests, and contours to accommodate clasp assemblies.

A favorable response to any deep restorations, endodontic therapy, and the results of periodontal treatment should be established before the removable partial denture is fabricated. If the prognosis of a tooth under treatment becomes unfavorable, its loss can be compensated for by a change in the removable partial denture design. If teeth are lost after the removable partial denture is fabricated, then the removable partial denture must be added to or replaced. Most removable partial denture designs do not lend themselves well to later additions, although this possibility should be considered in the original design of a denture. Every diagnostic aid should be used to determine which teeth are to be used as abutments or are potential abutments for future designs. When an original abutment is lost, it is extremely difficult to effectively modify the removable partial denture to use the next adjacent tooth as a retaining unit.

It is sometimes possible to design a removable partial denture so that a single posterior abutment that is questionable can be retained and used to support one end of a tooth-supported base. Then, if that posterior abutment was lost, it could be replaced with a distal extension base (see Figure 12-25). Such a design must include provision for future indirect retention, flexible clasping on the remaining terminal abutment, and provision for establishing tissue support by a secondary impression. Anterior abutments, which are considered poor risks, may not be so freely used because of the problems involved in adding a new abutment retainer when the original one is lost. Such questionable teeth should be treatment planned for extraction in favor of a better abutment in the original treatment plan.

Classification of Abutment Teeth

The subject of abutment preparations may be grouped as follows: (1) those abutment teeth that require only minor modifications to their coronal portions, (2) those that are to have restorations other than complete coverage crowns, and (3) those that are to have crowns (complete coverage).

Abutment teeth that require only minor modifications include teeth with sound enamel, those with small restorations not involved in the removable partial denture design, those with acceptable restorations that will be involved in the removable partial denture design, and those that have existing crown restorations requiring minor modification that will not jeopardize the integrity of the crown. The latter may exist as an individual crown or as the abutment of a fixed partial denture.

The use of unprotected abutments has been discussed previously. Although complete coverage of all abutments may be desirable, it is not always possible or practical. The decision to use unprotected abutments involves certain risks of which the patient must be advised and includes responsibility for maintaining oral hygiene and caries control. Making crown restorations fit existing denture clasps is a difficult task; however, the fact that it is possible to do may influence the decision to use uncrowned but otherwise sound teeth as abutments.

Complete coverage restorations provide the best possible support for occlusal rests. If the patient’s economic status or other factors beyond the control of the dentist prevent the use of complete coverage restorations, then an amalgam alloy restoration, if properly condensed, is capable of supporting an occlusal rest without appreciable flow for a long period. Any existing silver amalgam alloy restoration about which there is any doubt should be replaced with new amalgam restorations. This should be done before guiding planes and occlusal rest seats are prepared, to allow the restoration to reach maximum strength and be polished.

Continued improvement in dimensional stability, strength, and wear resistance of composite resin restorations will add another dimension to the preparation and modification of abutment teeth for removable partial dentures that should be less invasive than placement of complete coverage restorations and more economical.

Sequence of Abutment Preparations on Sound Enamel or Existing Restorations

Abutment preparations on sound enamel or on existing restorations that have been judged as acceptable should be done in the following order:

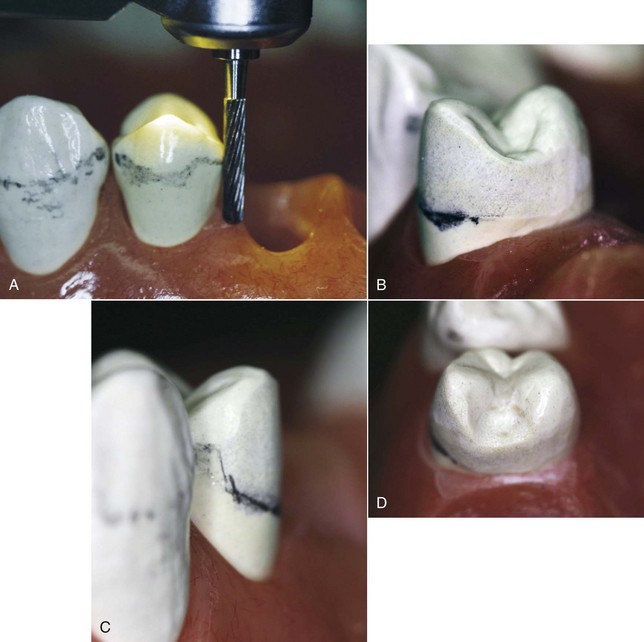

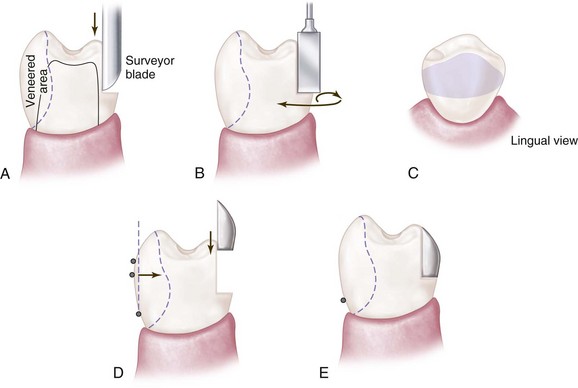

Figure 14-1 Abutment contours should be altered during mouth preparations in the following sequence. A, The proximal surface is prepared parallel to the path of placement to create a guiding plane. B, Height of contour on the buccal and lingual surfaces is lowered when necessary to permit the retentive clasp terminus to be located within the gingival third of the crown, bracing part of the retentive arm at the junction of the middle and gingival thirds of the crown, and the reciprocal clasp arm on the opposite side of tooth to be placed no higher than the cervical portion of the middle third of the crown. C, The area of the tooth at which the retentive clasp arm originates should be altered if necessary to permit a more direct approach to the gingival third of the tooth: (1) incorrect position of retentive clasp arm; (2) area of tooth modified to accommodate better position of retentive clasp arm; (3) more ideal position of retentive clasp arm. D, Occlusal rest preparation that will direct occlusal forces along the long axis of the tooth should be the final step in mouth preparations.

Abutment Preparations Using Conservative Restorations

Conventional inlay preparations are permissible on the proximal surface of a tooth not to be contacted by a minor connector of the removable partial denture. On the other hand, proximal and occlusal surfaces that support minor connectors and occlusal rests require somewhat different treatment. The extent of occlusal coverage (i.e., whether cusps are covered) will be governed by the usual factors, such as the extent of caries, the presence of unsupported enamel walls, and the extent of occlusal abrasion and attrition.

When an inlay is the restoration of choice for an abutment tooth, certain modifications of the outline form are necessary. To prevent the buccal and lingual proximal margins from lying at or near the minor connector or the occlusal rest, these margins must be extended well beyond the line angles of the tooth. This additional extension may be accomplished by widening the conventional box preparation. However, the margin of a cast restoration produced for such a preparation may be quite thin and may be damaged by the clasp during placement or removal of the removable partial denture. This hazard may be avoided by extending the outline of the box beyond the line angle, thus producing a strong restoration-to-tooth junction.

In this type of preparation, the pulp is particularly vulnerable unless the axial wall is curved to conform to the external proximal curvature of the tooth. When caries is of minimal depth, the gingival seat should have an axial depth at all points about the width of a No. 559 fissure bur. It is of utmost importance that the gingival seat be placed where it can be easily accessed to maintain good oral hygiene. The proximal contour necessary to produce the proper guiding plane surface and the close proximity of the minor connector render this area particularly vulnerable to future caries. Every effort should be made to provide the restoration with maximum resistance and retention, as well as with clinically imperceptible margins. The first requisite can be satisfied by preparing opposing cavity walls 5 degrees or less from parallel and producing flat floors and sharp, clean line angles.

It is sometimes necessary to use an inlay on a mandibular first premolar for the support of an indirect retainer. The narrow occlusal width bucco-lingually and the lingual inclination of the occlusal surface of such a tooth often complicate the two-surface inlay preparation. Even the most exacting occlusal cavity preparation often leaves a thin and weak lingual cusp remaining.

Abutment Preparations Using Crowns

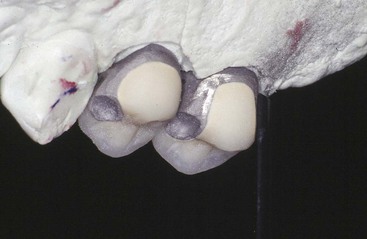

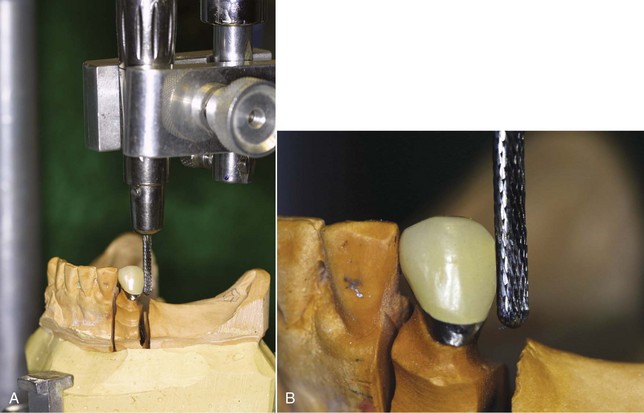

When multiple crowns are to be restored as removable partial denture abutments, it is best that all wax patterns be made at the same time. A cast of the arch with removable dies may be used if they are stable and sufficiently keyed for accuracy. If preferred, contouring wax patterns and making them parallel may be done on a solid cast of the arch (Figure 14-2), with individual dies used to refine margins. Modern impression materials and indirect techniques make either method equally satisfactory.

Figure 14-2 Solid cast of multiple abutment crowns for a removable partial denture. Wax patterns for crown #21, #28, #30, and #31 can be completed at the same time using the identical cast orientation. This allows control of the path of insertion features on all fitting surfaces of the removable prostheses.

The same sequence for preparing teeth in the mouth applies to the contouring of wax patterns. After the cast has been placed on the surveyor to conform to the selected path of placement and after the wax patterns have been preliminarily carved for occlusion and contact, proximal surfaces that are to act as guiding planes are carved parallel to the path of placement with a surveyor blade. Guiding planes are extended from the marginal ridge to the junction of the middle and gingival thirds of the tooth surface involved. One must be careful not to extend the guiding plane to the gingival margin because the minor connector must be relieved when it crosses the gingivae. A guiding plane that includes the occlusal two thirds or even one third of the proximal area is usually adequate without endangering gingival tissues.

After the guiding planes are parallel and any other contouring to accommodate the removable partial denture design is accomplished, occlusal rest seats are carved in the wax pattern. This method has been outlined in Chapter 6.

It should be emphasized that critical areas prepared in wax should not be destroyed by careless spruing or polishing. The wax pattern should be sprued to preserve paralleled surfaces and rest areas. Polishing should consist of little more than burnishing. Rest seat areas should need only refining with round finishing burs. If some interference by spruing is unavoidable, the casting must be returned to the surveyor for proximal surface refinement. This can be done accurately with the aid of a handpiece holder attached to the vertical spindle of the surveyor or some similar machining device.

One of the advantages of making cast restorations for abutment teeth is that mouth preparations that would otherwise have to be done in the mouth may be done on the surveyor with far greater accuracy. It is generally impossible to make several proximal surfaces parallel to one another when preparing them intraorally. The opportunity for contouring wax patterns and making them parallel on the surveyor in relation to a path of placement should be used to its full advantage whenever cast restorations are being made.

The ideal crown restoration for a removable partial denture abutment is the complete coverage crown, which can be carved, cast, and finished to ideally satisfy all requirements for support, stabilization, and retention without compromise for cosmetic reasons (Figure 14-3). Porcelain veneer crowns can be made equally satisfactory but only by the added step of contouring the veneered surface on the surveyor before the final glaze. If this is not done, retentive contours may be excessive or inadequate.

Figure 14-3 Metal ceramic crowns for teeth #4 and #5 demonstrating occlusal rests in metal and evidence of palatal finishing procedures. The distal surface of #4 provides a guide-plane surface that is continued onto a portion of the lingual surface for maximum stabilization.

The three-quarter crown does not permit creation of retentive areas as does the complete coverage crown. However, if buccal or labial surfaces are sound and retentive areas are acceptable or can be made so by slight modification of tooth surfaces, the three-quarter crown is a conservative restoration of merit. The same criteria apply in the decision to leave a portion of an abutment unprotected, as in the decision to leave any tooth unprotected that is to serve as a removable partial denture abutment.

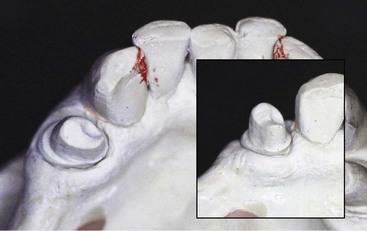

Regardless of the type of crown used, preparation should be made to provide the appropriate depth for the occlusal rest seat. This is best accomplished by altering the axial contours of the tooth to the ideal before preparing the tooth and creating a depression in the prepared tooth at the occlusal rest area (Figure 14-4). Because the location of occlusal rests is established during treatment planning, this information will be known in advance of any tooth preparations. If, for example, double occlusal rests are to be used, this will be known so that the tooth can be prepared to accommodate the depth of both rests. It is inexcusable when waxing a pattern to find that a rest seat has to be made shallower than is desirable because of post-treatment planning. It can also create serious problems when a rest seat has to be made shallow in an existing crown or inlay because its thickness is not known. The opportunity for creating an ideal rest seat (if it has been properly treatment planned) depends only on the few seconds it takes to create a space for it.

Figure 14-4 Metal-ceramic crown preparation on tooth #21 shows mesial-occlusal (MO) rest space provided in the crown preparation at the mesial. Inset picture gives a perspective of the vertical height this provides for the rest to be prepared in the wax pattern.

Ledges on Abutment Crowns

In addition to providing abutment protection, more ideal retentive contours, definite guiding planes, and optimum occlusal rest support, complete coverage restorations on teeth used as removable partial denture abutments offer still another advantage not obtainable on natural teeth. This is the crown ledge or shoulder, which provides effective stabilization and reciprocation.

The functions of the reciprocal clasp arm have been stated in Chapter 6. Briefly, these are reciprocation, stabilization, and auxiliary indirect retention. Any rigid reciprocal arm may provide horizontal stabilization if it is located on axial surfaces parallel to the path of placement. To a large extent, because it is placed at the height of convexity, a rigid reciprocal arm may also act as an auxiliary indirect retainer. However, its function as a reciprocating arm against the action of the retentive clasp arm is limited to stabilization against possible orthodontic movement when the denture framework is in its terminal position. Such reciprocation is needed when the retentive clasp produces an active orthodontic force because of accidental distortion or improper design. Reciprocation, to prevent transient horizontal forces that may be detrimental to abutment stability, is most needed when the restoration is placed or when a dislodging force is applied. Perhaps the term orthodontic force is incorrect, because the term signifies a slight but continuous influence that would logically reach equilibrium when the tooth is orthodontically moved. Instead, the transient forces of placement and removal are intermittent but forceful, which can lead to periodontal destruction and eventual instability rather than to orthodontic movement.

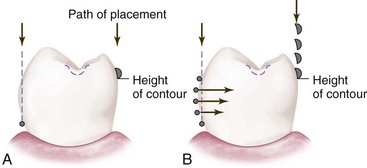

True reciprocation is not possible with a clasp arm that is placed on an occlusally inclined tooth surface because it does not become effective until the prosthesis is fully seated. When a dislodging force is applied, the reciprocal clasp arm, along with the occlusal rest, breaks contact with the supporting tooth surfaces, and they are no longer effective. Thus, as the retentive clasp flexes over the height of contour and exerts a horizontal force on the abutment, reciprocation is nonexistent just when it is needed most (Figure 14-5).

Figure 14-5 A, Incorrect relationship of retentive and reciprocal clasp arms to each other when the removable partial denture framework is fully seated. As the retentive clasp arm flexes over the height of contour during placement and removal, the reciprocal clasp arm cannot be effective because it is not in contact with the tooth until the denture framework is fully seated. B, Horizontal forces applied to the abutment tooth as the retentive clasp flexes over the height of contour during placement and removal. Open circles at the top and bottom illustrate that the retentive clasp is passive only at its first contact with the tooth during placement and when in its terminal position with the denture fully seated. During placement and removal, a rigid clasp arm placed on the opposite side of the tooth cannot provide resistance against these horizontal forces. See Figure 14-6 for a method to ensure true reciprocation.

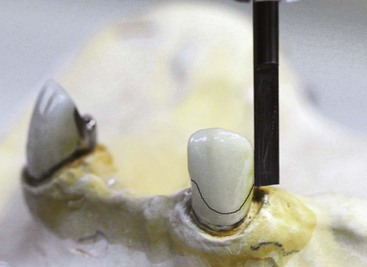

True reciprocation can be obtained only by creating a path of placement for the reciprocal clasp arm that is parallel to other guiding planes. In this manner, the inferior border of the reciprocal clasp makes contact with its guiding surface before the retentive clasp on the other side of the tooth begins to flex (Figure 14-6). Thus reciprocation exists during the entire path of placement and removal. A ledge on the abutment crown acts as a terminal stop for the reciprocal clasp arm. It also augments the occlusal rest and provides indirect retention for a distal extension removable partial denture.

Figure 14-6 A, Preparation of the ledge in a wax pattern with a surveyor blade parallel to the path of placement. B, Refinement of the ledge on casting, using a suitable stone or milling device in a handpiece attached to the dental surveyor or a specialized drill press for the same purpose. C, Approximate width and depth of the ledge formed on the abutment crown, which will permit the reciprocal clasp arm to be inlaid within the normal contours of the tooth. D, True reciprocation throughout the full path of placement and removal is possible when the reciprocal clasp arm is inlaid onto the ledge on the abutment crown. E, Direct retainer assembly is fully seated. The reciprocal arm restores the lingual contour of the abutment.

A ledge on an abutment crown has still another advantage. The usual reciprocal clasp arm is half-round, and therefore convex, and is superimposed on and increases the bulk of an already convex surface. A reciprocal clasp arm built on a crown ledge is actually inlayed into the crown and reproduces more normal crown contours (see Figure 14-6). The patient’s tongue then contacts a continuously convex surface rather than the projection of a clasp arm. Unfortunately, the enamel is not thick enough nor the tooth so shaped that an effective ledge can be created on an unrestored tooth. Narrow enamel shoulders are sometimes used as rest seats on anterior teeth, but these do not provide the parallelism that is essential to reciprocation during placement and removal.

The crown ledge may be used on any complete or three-quarter crown restored surface that is opposite the retentive side of an abutment tooth. It is used most frequently on premolars and molars but also may be used on canine restorations. It is not ordinarily used on buccal surfaces for reciprocation against lingual retention because of the excessive display of metal, but it may be used just as effectively on posterior abutments when esthetics is not a factor.

The fact that a crown ledge is to be used should be known in advance of crown preparation to ensure sufficient removal of tooth structure in this area. Although a shoulder or ledge is not included in the preparation itself, adequate space must be provided so that the ledge may be made sufficiently wide and the surface above it made parallel to the path of placement. The ledge should be placed at the junction of the gingival and middle thirds of the tooth, curving slightly to follow the curvature of the gingival tissues. On the side of the tooth where the clasp arm will originate, the ledge must be kept low enough to allow the origin of the clasp arm to be wide enough for sufficient strength and rigidity.

In forming the crown ledge, which is usually located on the lingual surface, the wax pattern of the crown is completed except for refinement of the margins before the ledge is carved. After the proximal guiding planes and the occlusal rests and retentive contours are formed, the ledge is carved with the surveyor blade so that the surface above is parallel to the path of placement. Thus a continuous guiding plane surface will exist from the proximal surface around the lingual surface.

The full effectiveness of the crown ledge can be achieved only when the crown is returned to the surveyor for refinement after casting. To afford true reciprocation, the crown casting must have a surface above the ledge that is parallel to the path of placement. This can be accomplished with precision only by machining the casting parallel to the path of placement with a handpiece holder in the surveyor or some other suitable machining device (Figure 14-7).

Figure 14-7 A milling machine used to prepare parallel surfaces, internal rest seats, lingual grooves, and ledges in cast restorations. Such a device permits more precise milling than is possible with a dental handpiece attached to the dental surveyor. To be effective, the cast must be positioned on the drill in such a manner that the previously established path of placement is maintained. A movable stage or base therefore should be adjustable until the relation of the cast to the axis of the drill has been made the same as that obtained when the cast was on the dental surveyor.

Similarly, the parallelism of proximal guiding planes needs to be perfected after casting and polishing. Although it is possible to approximate parallelism and, at the same time, form the crown ledge on the wax pattern with a surveyor blade, some of its accuracy is lost in casting and polishing. The use of suitable burs such as No. 557, 558, and 559 fissure burs and true cylindrical carborundum stones in the handpiece holder permits the paralleling of all guiding planes on the finished casting with the accuracy necessary for the effectiveness of those guiding plane surfaces.

The reciprocal clasp arm is ultimately waxed on the investment cast so that it is continuous with the ledge inferiorly and contoured superiorly to restore the crown contour, including the tip of the cusp. It is obvious that polishing must be controlled so as not to destroy the form of the shoulder that was prepared in wax or the parallelism of the guiding plane surface. It is equally vital that the removable partial denture casting be finished with great care so that the accuracy of the counterpart is not destroyed. Modern investments, casting alloys, and polishing techniques make this degree of accuracy possible.

Spark Erosion

Spark erosion technology is a highly advanced system for producing the ultimate in precision fit of the reciprocal arm to the ledge on the casting. This technology uses a tool system that permits repositioning of the casting with great accuracy and an electric discharge machine that is programmed to erode minute metal particles through periodic spark intervals.

Regardless of the method or technique used, it is imperative that the predetermined cast orientation be maintained to ensure that ledges and proximal guide planes remain parallel.

Veneer Crowns for Support of Clasp Arms

For cosmetic reasons, resin and porcelain veneer crowns are used on abutment teeth that would otherwise display an objectionable amount of metal. They may be present in the form of porcelain veneers retained by pins and cemented to the crown; porcelain fused directly to a cast metal substructure; porcelain fused to a machined coping; cast porcelain; pressed ceramic crowns; computer-assisted designed and machined ceramic restorations; or acrylic-resin processed directly to a cast crown. The development of abrasion-resistant composites offers materials suitable for veneering that can withstand clasp contact, thereby eliminating an undesirable display of metal.

Veneer crowns must be contoured to provide suitable retention. This means that the veneer must be slightly overcontoured and then shaped to provide the desired undercut for the location of the retentive clasp arm (Figure 14-8). If the veneer is of porcelain, this procedure must precede glazing, and if it is of resin, it must precede final polishing. If this important step in making veneered abutments is neglected or omitted, excessive or inadequate retentive contours may result.

Figure 14-8 A porcelain veneer crown is resurveyed following adjustment, glazing, and polishing. It is important to survey crowns returned from the laboratory before cementation. The best time to ensure control of all abutment contours for a removable partial denture is when surveyed crowns are used and they are resurveyed before permanent placement.

In limited clinical trials, porcelain laminates demonstrated resistance to wear of 5-year equivalence. The porcelain, however, resulted in slight wear on the clasps.

The flat underside of the cast clasp makes sufficient contact with the surface of the veneer so that abrasion of a resin veneer may result. Although the underside of the clasp may be polished (with some loss in accuracy of fit), abrasion results from the trapping and holding of food debris against the tooth surface as the clasp moves during function. Therefore, unless the retentive clasp terminal rests on metal, glazed porcelain should be used to ensure the future retentiveness of the veneered surface. Present-day acrylic-resins, which are cross-linked copolymers, will withstand abrasion for considerable time, but not nearly to the same degree as porcelain. Therefore acrylic-resin veneers are best used in conjunction with metal that supports the half-round clasp terminal.

Splinting of Abutment Teeth

Often, a tooth is considered too weak to use alone as a removable partial denture abutment because of the short length or excessive taper of a single root, or because of bone loss resulting in an unfavorable crown-to-root ratio. In such instances, splinting to the adjacent tooth or teeth can be used as a means of improving abutment support. Thus, two single-rooted teeth serve as a multi-rooted abutment.

Splinting should not be used to retain a tooth that would otherwise be condemned for periodontal reasons. When the length of service of a restoration depends on the serviceability of an abutment, any periodontally questionable tooth should be condemned in favor of using an adjacent healthy tooth as the abutment, even though the span is increased one tooth by doing so.

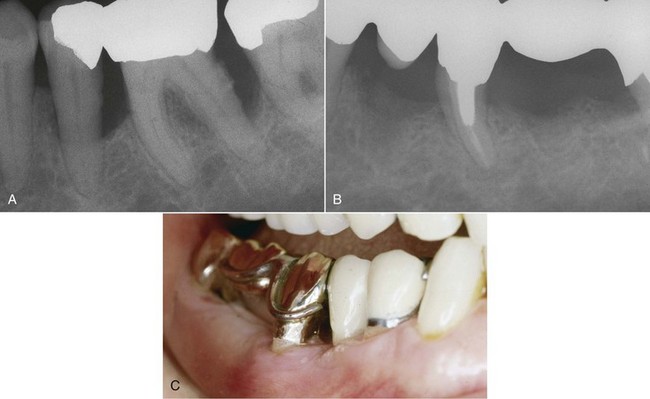

The most common application of the use of multiple abutments is the splinting of two premolars or a first premolar and a canine (Figure 14-9). Mandibular premolars generally have round and tapered roots, which are easily loosened by rotational, as well as by tipping, forces. They are the weakest of the posterior abutments. Maxillary premolars also often have tapered roots, which may make them poor risks as abutments, particularly when they will be called on to resist the leverage of a distal extension base. Such teeth are best splinted by casting or soldering two crowns together. When a first premolar to be used as an abutment has poor root form or support, it is best that it be splinted to the stronger canine.

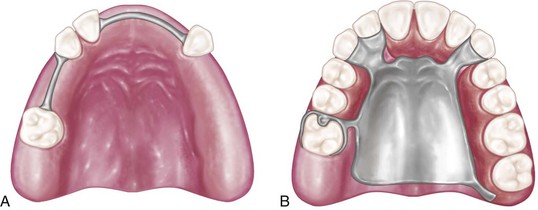

Figure 14-9 First premolars and canines have been splinted in this Class I, modification 1 partially edentulous arch. The splint bar was added to provide cross-arch stabilization for splinted abutments and to support and retain the anterior segment of the removable restoration. The prospective longevity of the abutments has been enhanced.

Anterior teeth on which lingual rests are to be placed often must be splinted together to avoid orthodontic movement of individual teeth. Mandibular anterior teeth are seldom used for support, but if they are, splinting of the teeth involved is advisable. When splinting is impossible, individual lingual rests on cast restorations may be slightly inclined apically to avoid possible tooth displacement, or lingual rests may be used in conjunction with incisal rests, slightly engaging the labial surface of the teeth.

Lingual rests should always be placed as low on the cingulum as possible, and single anterior teeth, other than canines, should not be used for occlusal support. Where lingual rests are used on central and lateral incisors, as many teeth as possible should be included to distribute the load, thereby minimizing the force on any one tooth. Even so, some movement of individual teeth is likely to occur, particularly when they are subjected to the forces of indirect retention or when bone support is compromised. This is best avoided by splinting several teeth with united cast restorations. The condition of the teeth and cosmetic considerations will dictate whether complete crowns, three-quarter crowns, pin ledge inlays, resin-bonded retainers, or composite restorations will be used for this purpose.

Splinting of molar teeth for multiple abutment support is less frequently used because they are generally multi-rooted. A two- or three-rooted tooth that is not strong enough alone is probably a poor abutment risk. However, there may be notable exceptions when a molar abutment would benefit from the effect of splinting, as in a hemi-sected molar root (Figure 14-10).

Figure 14-10 A, Periodontal disease required removal of #30 distal and #31 mesial roots. B, The first premolar and hemi-sected roots were splinted using a five-unit fixed partial denture. C, Fixed prosthesis provided cross-arch support, stability, and retention to a Kennedy Class II removable partial denture.

Use of Isolated Teeth as Abutments

The average abutment tooth is subjected to some distal tipping, rotation, torquing, and horizontal movement, all of which must be held to a minimum by the quality of tissue support and the design of the removable partial denture. The isolated abutment tooth, however, is subjected also to mesial tipping caused by lack of proximal contact. Despite indirect retention, some lifting of the distal extension base is inevitable, causing torque to the abutment.

In a tooth-supported prosthesis, an isolated tooth may be used as an abutment by including a fifth abutment for additional support. Thus rotational and horizontal forces are resisted by the additional stabilization obtained from the fifth abutment. When two such isolated abutments exist, a sixth abutment should be included for the same reason. Thus the two canines, the two isolated premolars, and two posterior teeth are used as abutments.

In contrast, an isolated anterior abutment adjacent to a distal extension base usually should be splinted to the nearest tooth by means of a fixed partial denture. The effect is twofold: (1) the anterior edentulous segment is eliminated, thereby creating an intact dental arch anterior to the edentulous space; and (2) the isolated tooth is splinted to the other abutment of the fixed partial denture, thereby providing multiple abutment support. Splinting should be used here only to gain multiple abutment support rather than to support an otherwise weak abutment tooth.

Although splinting is advocated for abutment teeth that are considered too weak to risk being used alone, a single abutment standing alone in the dental arch anterior to a distal extension basal seat generally requires the splinting effect of a fixed partial denture (Figures 14-11 and 14-12). Even though the form and length of the root and the supporting bone seem to be adequate for an ordinary abutment, the fact that the tooth lacks proximal contact endangers the tooth when it is used to support a distal extension base removable partial denture.

Figure 14-11 Lone-standing premolar should be splinted to the canine with a fixed partial denture. Not only will the design of the removable partial denture be simplified, but the longevity of abutment service by the premolar will be greatly extended.

Figure 14-12 A, Isolated abutments have been splinted using splint bars. B, The removable partial denture is more adequately supported by the splinting mechanism shown in A than could be realized with isolated abutments.

A second factor that may influence the decision to use an isolated tooth as an abutment is an esthetic consideration. However, neither esthetics nor economics should deter the dentist from recommending to the patient that an isolated tooth to be used as a terminal abutment should be given the advantage of splinting by means of a fixed partial denture. If compromises are necessary, the patient must assume responsibility for use of the isolated tooth as an abutment.

The economic aspect of the use of fixed restorations as part of the mouth preparations for a removable partial denture is essentially the same as that for any other splinting procedure: the best design of the fixed partial denture that will ensure the longevity of its service makes the additional procedure and expense necessary. Although it must be recognized that economic considerations, combined with a particularly favorable prognosis of an isolated tooth, may influence the decision to forego the advantages of using a fixed partial denture, the original treatment plan should include this provision, even though the alternative method may be accepted for economic reasons.

Missing Anterior Teeth

When a removable partial denture is used to replace missing posterior teeth, especially in the absence of distal abutments, any additional missing anterior teeth are best replaced by means of fixed restorations rather than included in the removable partial denture. In any distal extension situation, some anteroposterior rotational action will result from the addition of an anterior segment to the denture. The ideal treatment plan, which would consider the anterior edentulous space separately, may result in conflict with economic and esthetic realities. Each situation must be treated according to its own merits. Often the best esthetic result can be obtained by replacing missing anterior teeth and tissues with the removable partial denture rather than with a fixed restoration. From a biomechanical standpoint, however, it is generally advisable that a removable partial denture should replace the missing posterior teeth only after the remainder of the anterior arch has been made intact by fixed restorations.

Although the need for compromise is recognized, the decision to include an anterior segment on the denture depends largely on the support available for that part of the removable partial denture. The greater the number of natural anterior teeth remaining, the better is the available support for the edentulous segment. If definite rest seats can be prepared on multiple abutments, the anterior segment may be treated as any other tooth-bounded modification space. Sound principles of rest support apply just as much as elsewhere in the arch. Inclined tooth surfaces should not be used for occlusal support, nor should rests be placed on unprepared lingual surfaces. The best possible support for an anterior segment is multiple support extending, if possible, posteriorly across prepared lingual rest seats on the canine teeth to mesio-occlusal rest seats on the first premolars. Such support would permit the missing anterior teeth to be included in the removable partial denture, often with some cosmetic advantages over fixed restorations.

In some instances, the replacement of anterior teeth by means of a removable partial denture cannot be avoided. However, without adequate tooth support, any such prosthesis will lack the stability that would result from replacing only the posterior teeth with the removable partial denture and the anterior teeth with fixed restorations. When anterior teeth have been lost through accident or have been missing for some time, resorption of the anterior residual ridge may have progressed to the point that neither fixed nor removable pontics may be butted to the residual ridge. In such instances, for reasons of esthetics and orofacial tissue support, the missing teeth must be replaced with a denture base supporting teeth that are more nearly in their original position, considerably forward from the residual ridge. Although such teeth may be positioned to better cosmetic advantage, the contouring and coloring of a denture base to be esthetically pleasing require the maximum artistic effort of both the dentist and the technician. Such a removable partial denture, both from an esthetic and a biomechanical standpoint, is one of the most difficult of all prosthetic restorations. However, a splint bar, connected by abutments on both sides of the edentulous space, will provide much-needed support and retention to the anterior segment of the removable partial denture. Because the splint bar will provide vertical support, rest seats on abutments adjacent to the edentulous area need not be prepared, thus simplifying an anterior restoration to some extent.

The concept of a dual path of placement to enhance the esthetic replacement of missing anterior teeth with a removable partial denture is recognized. Sources of information on this concept are made available in the “Selected Reading Resources” of this text under “Partial Denture Design.”

Temporary Crowns When A Removable Partial Denture Is Being Worn

Occasionally, an existing removable partial denture must remain serviceable while the mouth is being prepared for a new prosthesis. In such situations, temporary crowns must be made that will support the old removable partial denture and will not interfere with its placement and removal. Acrylic-resin temporary crowns that duplicate the original form of the abutment teeth must be made.

The technique for making temporary crowns to fit direct retainers is similar to that used for other types of acrylic-resin temporary crowns. The principal difference is that an impression, made with an elastic impression material, must be made of the entire arch with the existing removable partial denture in place. It is necessary that the removable partial denture remain in the impression when it is removed from the mouth. If it remains in the mouth, it must be removed and inserted into the impression in its designated position. The impression with the removable partial denture in place is disinfected, wrapped in a wet paper towel (if irreversible hydrocolloid was used as the impression material) or placed in a plastic bag, and set aside while the tooth or teeth are being prepared for new crowns.

After the preparations are completed and the impressions and jaw relation records have been made, the prepared teeth are dried and lubricated. The original impression is trimmed to eliminate any excess, undercuts, and interproximal projections that would interfere with the replacement of the impression in the mouth.

The methyl methacrylate acrylic-resins, composites, copolymers, and fiber-reinforced resins may serve as excellent materials for temporary crowns in conjunction with removable partial dentures. Making temporary crowns requires a small mixing cup or dappen dish; a cement spatula; and a small, disposable, plastic syringe. Autopolymerizing acrylic-resin of the appropriate tooth color is placed in the cup or dappen dish, and monomer is added to make a slightly viscous mix. The volume should be slightly in excess of the amount estimated to fabricate the temporary restorations. The mix should be spatulated to a smooth consistency and the mix immediately poured into the barrel of the disposable syringe. A small amount of the mix should be injected over and around the margins of the prepared teeth. The remaining material should be injected into the impression of the prepared teeth. The impression is seated into the mouth, where the dentist holds it in place until sufficient time has elapsed for it to reach a stiff, rubbery stage, or a consistency recommended by the manufacturer. This again must be based on experience with the particular resin used. At this time, the impression is removed. The crowns may remain in the impression. If so, they are stripped out of the impression, all excess is trimmed away with scissors, and the crowns are reseated on the prepared abutments. The removable partial denture is then removed from the impression and reseated in the mouth onto the temporary crowns, which should be in a stiff-rubbery state. The patient may bring the teeth into occlusion to reestablish the former position and occlusal relationship of the existing removable partial denture.

After the resin crown or crowns have polymerized, the removable partial denture is removed and the crowns remain on the teeth. These are then carefully removed, contoured to accommodate oral hygiene access, trimmed, polished, and temporarily cemented. The result is a temporary crown that restores the original abutment contours and allows the removable partial denture to be placed and removed without interference, while temporarily providing the same support to the denture that existed before the teeth were prepared.

Cementation of Temporary Crowns

Cementation of temporary crowns may require slight relief of the internal surface of the crowns to accommodate the temporary cement and to facilitate removal. The temporary cement should be thin and applied only to the inside gingival margin of the crowns to ensure complete seating. As soon as the temporary cement has hardened, the occlusion should be checked and adjusted accordingly. Regardless of the type of temporary cement used, any excess that might irritate the gingivae should be removed.

Fabricating Restorations to Fit Existing Denture Retainers

It is often necessary that an abutment tooth be restored with a complete crown (or other restoration) that will fit the inside of the clasp of an otherwise serviceable removable partial denture. One technique for doing so is simple enough, but it requires that an indirect-direct pattern be made and therefore justifies a fee for service above that required for the usual restoration.

The technique for making a crown to fit the inside of a clasp is as follows: An irreversible hydrocolloid impression of the mouth is made with the removable partial denture in place. This impression, which is used to make the temporary crown, is wrapped in a wet paper towel or placed in a plastic bag and set aside while the tooth is being prepared. Even though several abutment teeth are to be restored, it is usually necessary that each temporary restoration be completed before the next one is begun. This is necessary so that the original support and occlusal relationship of the removable partial denture can be maintained as each new temporary crown is being made. During preparation of the abutment tooth, the removable partial denture is replaced frequently to ascertain that sufficient tooth structure has been removed to allow for the thickness of the casting. When the preparation is completed, an individual impression of the tooth is obtained from which a stone die is made. A temporary crown is then made in the original irreversible hydrocolloid impression, as outlined in the preceding paragraphs. It is trimmed, polished, and temporarily cemented, and the removable partial denture is returned to the mouth. The patient is dismissed after the excess cement has been removed.

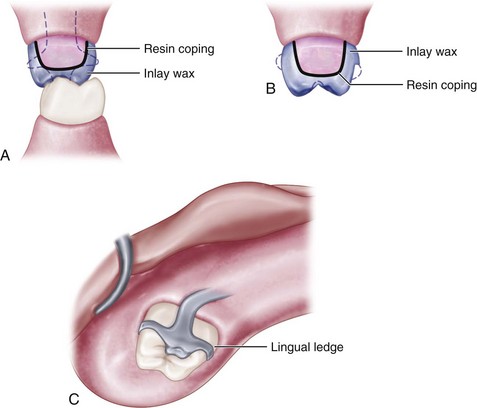

On the stone die made from the individual impression, a thin, autopolymerizing resin coping will be formed with a brush technique. The stone die should first be trimmed to the finishing line of the preparation, which is then delineated with a pencil, and the die painted with a tinfoil substitute. A separating material, such as a tinfoil substitute, should be used and will form a thin film on a cold, dry surface. Not all tinfoil substitutes are suitable for this purpose. With autopolymerizing resin powder and liquid in separate dappen dishes and a fine brush, a coping of resin of uniform thickness is painted onto the die. This should extend not quite to the pencil line representing the limit of the crown preparation. After hardening, the resin coping may be removed, inspected, and trimmed if necessary. The thin film of foil substitute should be removed before the coping is reseated onto the die.

The wax pattern buildup on the resin coping is usually not begun until the patient returns. A sequence using a functional chew-in technique for occlusion would be followed establishing proximal contact and contours appropriate for the clasp assembly as outlined below.

First, the occlusal portion of the wax pattern is established by having the patient close into maximum intercuspation, followed by excursive movements (Figure 14-13A). The wax pattern is returned to the cast, and additions are made to dull areas as required. The process is repeated until a smooth occlusal registration has been obtained. Except for narrowing of the occlusal surface and carving of grooves and spillways, this will be the occlusal anatomy of the finished restoration.

Figure 14-13 Making of the cast crown to fit an existing removable partial denture clasp. A, Thin acrylic-resin coping is made first on the individual die of a prepared tooth. Inlay wax is then added and coping placed onto the prepared tooth where occlusal surfaces and contact relations are established directly in the mouth. The clasp assembly is warmed with a needlepoint flame only enough to soften the inlay wax, and the removable partial denture is placed into the mouth, where it is guided gently into place by the opposing occlusion. This step must be repeated several times and excess wax removed or wax added until full supporting contact with the underside of the clasp assembly has been established, with the denture fully seated. Usually, the wax pattern withdraws with the denture and must be gently teased out of the clasp each time. B, The wax pattern is then placed back onto the individual die to complete the occlusal anatomy and refine the margins. Excess wax remaining below the impression of the retentive clasp arm must be removed, but the wax ledge may be left below the reciprocal clasp arm. C, Finished casting in the mouth. The terminus of the retentive clasp is then readapted to engage the undercut. It is frequently necessary to remove some interference from casting, as indicated by articulating paper placed between the clasp and the crown, until the clasp is fully seated.

The second step is the addition of sufficient wax to establish contact relations with the adjacent tooth. At this time, the occlusal relation of the marginal ridges also must be established. Next, wax is added to buccal and lingual surfaces where the clasp arms will contact the crown, and the wax pattern is again reseated in the mouth. The clasp arms, minor connectors, and occlusal rests involved in the removable partial denture are carefully warmed with a needlepoint flame, carefully avoiding any adjacent resin, and the removable partial denture is positioned in the mouth and onto the wax pattern (Figure 14-13B). Several attempts may be necessary until the removable partial denture is fully seated and the components of the clasp are clearly recorded in the wax pattern. Each time the removable partial denture is removed, the pattern will draw with it and must be teased out of the clasp.

When contact with the clasp arms and the occlusal relation of the removable partial denture have been established satisfactorily, the temporary crown may be replaced and the patient dismissed. The crown pattern is completed on the die by narrowing the occlusal surface bucco-lingually, adding grooves and spillways, and refining the margins. Any wax ledge remaining below the reciprocal clasp arm may be left to provide some of the advantages of a crown ledge that were described earlier in this chapter. Excess wax remaining below the retentive clasp arm, however, must be removed to permit the adding of a retentive undercut later (Figure 14-13 C).

If a veneer material is to be added, the veneer space must now be carved in the wax pattern. In such situations, the contour of the veneer may be recorded by making a stone matrix of the buccal surface, which can be repositioned on the completed casting to ensure the proper contour of the composite veneer.

The wax pattern must be sprued with care so that essential areas on the pattern are not destroyed. After casting, the crown should be subjected to a minimum of polishing because the exact form of the axial and occlusal surfaces must be maintained.

Because it is impossible to withdraw a clasp arm from a retentive undercut on the wax pattern, the casting must be made without any provision for clasp retention. After the crown has been tried in the mouth with the denture in place, the location of the retentive clasp terminal is identified by scoring the crown with a sharp instrument. Then the crown may be ground and polished slightly in this area to create a retentive undercut. The clasp terminal then may be carefully adapted into this undercut, thereby creating clasp retention on the new crown.

An alternate method for making crowns to fit existing retainers uses mounted casts with the removable prosthesis adapted to the working cast to develop occlusal surfaces for the involved crowns.

Ideally, all abutment teeth would best be protected with complete crowns before the removable partial denture is fabricated. Except for the possibility of recurrent caries caused by defective crown margins or gingival recession, abutment teeth so protected may be expected to give many years of satisfactory service in support, stabilization, and retention of the removable partial denture. Economically, a policy of insisting on complete coverage for all abutment teeth may well be justified from the long-term viewpoint. It must be recognized, however, that in practice, complete coverage of all abutment teeth is not always possible at the time of treatment planning. Many factors influence the future health status of an abutment tooth, some of which cannot be foreseen. It is necessary that the dentist be able to treat abutment teeth that later become defective so that their service as abutments may be restored and the serviceability of the removable partial denture maintained. Although not part of the original mouth preparations, this service accomplishes much the same objective by providing support, stability, and retention, and the dentist must be technically capable of providing this removable partial denture service when it becomes necessary.