Purposes, Processes, and Methods of Evaluation

1 Apply the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework to the evaluation process for children and their families.

2 List five primary reasons to conduct evaluations.

3 Discuss the variety of decisions pediatric occupational therapists make throughout the evaluation process.

4 Describe the specific steps pediatric occupational therapists follow in the process of evaluating children

5 Describe the primary evaluation methods commonly used in pediatric occupational therapy.

6 Discuss the major factors therapists should consider when selecting evaluation methods and measures.

7 Apply the knowledge gained in this chapter to specific case studies of children who have or are at risk for disabilities.

Those who observe human behavior must be vigilant when examining the details of the behavior and when relating those details to each other in the context of that behavior. Occupational therapists involved in the evaluation of children face this challenge daily. To examine fully a child’s occupational performance, the occupational therapist first analyzes how the physical demands and social expectations of the home, school, and community environments influence the child’s participation. After identifying the areas of occupation most important to the child and the caregivers, the occupational therapist assesses the child’s performance skills and performance patterns essential to his or her participation in everyday activities.

The evaluation process is one of the most fundamental, yet complex, aspects of occupational therapy services. According to the Standards of Practice for Occupational Therapy, evaluation is “the process of obtaining and interpreting data necessary for intervention. This includes planning for and documenting the evaluation process and results” (p. 663).2 On the basis of the evaluation results, the occupational therapist makes important decisions regarding the type and intensity of occupational therapy intervention. The following factors influence these decisions: how the occupational therapist views the evaluation process; whether the therapist is open to new ways of understanding the child and family; which methods and measures the therapist selects to evaluate the child; and how the therapist interprets and documents the evaluation data.

This chapter describes the occupational therapy evaluation for children and adolescents. The first section explains the purposes of evaluating children based on the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF).1 A case study illustrates the application of the OTPF to the evaluation of a child. The second section describes the evaluation process, including sequential steps used by pediatric occupational therapists. The third section describes the general methods, measures, and principles used in selecting and administering pediatric occupational therapy assessments.

Four primary concepts are reinforced throughout this chapter:

1. The evaluation of a child or adolescent is an ongoing, dynamic process that begins with the initial referral for therapy and continues throughout the intervention and discharge phases of occupational therapy services.

2. The views and priorities of the child’s primary caregiver and of the child are central throughout the evaluation process.

3. Evaluations should be ecologically and culturally valid.

4. The outcome of the evaluation is an in-depth understanding of the child’s participation in occupations meaningful to him or her and to the caregivers.

EVALUATION PURPOSES

Occupational therapists evaluate children and their environments to gather information needed to make decisions about intervention services. This section discusses the decisions that therapists make during the various steps of careful screening and comprehensive evaluation of children who have or are at risk for disabilities.

The five primary purposes of occupational therapy evaluation are as follows:

1. Comprehensive evaluation to develop an intervention plan

2. Screening to decide if further evaluation of the child is warranted

3. Eligibility or diagnostic testing to decide if the child is eligible for occupational therapy services or to assist in the diagnostic process

4. Reevaluation to determine the child’s progress in therapy and determine whether further therapy is warranted

5. Research or outcomes testing to evaluate the efficacy of intervention services and therapy outcomes

Comprehensive Evaluation for Intervention Planning

Comprehensive evaluation allows the occupational therapist to establish goals and plan intervention. The occupational therapist uses a top-down approach, assessing what the child wants and needs to do and then identifying those factors that act as supports or barriers to the child’s participation in those childhood occupations. Consistent with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF),56 the OTPF supports the notion that an individual’performance and participation are inextricably linked to context, activity demands, and client factors. Occupation-centered assessment of children “acknowledges the importance of individual activities that are part of a particular occupation, as well as the context, but is most concerned with the overall process of participation.”15 Initially the therapist develops an occupational profile of the child based on referral concerns, interviews with caregivers and the child (if possible), and direct observations of the child performingself-care, play, and school-related activities. This profile describes the child’s past occupational history and experiences, his or her current performance in occupational areas (e.g., self-help, play, and school activities), and the caregiver’s (and child’s) priorities regarding the child’s participation in everyday activities. After identifying the limitations on the child’s participation, the therapist develops a working hypothesis regarding possible reasons for identified problems and concerns. The occupational profile is the foundation for the next step in the evaluation process, which is the analysis of the child’s occupational performance.

The analysis of occupational performance includes an evaluation of the child’s physical, cognitive, and psychosocial performance and of important environmental factors that influence the child’s participation in everyday occupations. Evaluation of the child’s occupations consists of the child’s performance skills (e.g., motor skills, process skills), performance patterns (e.g., habits, routines, roles), contexts (e.g., cultural, physical, social, personal, spiritual, temporal), activity demands (e.g., objects, space demands, social demands, sequencing and timing, required actions, required body functions and structures), and child factors (e.g., body functions and body structures).

To gain an in-depth understanding of the child’s performance abilities and limitations, the occupational therapist evaluates the features of the environment in which the child performs the activities. Children and their families (Figure 7-1) are embedded in a network of social systems, including extended family, friends, neighbors, day care, schools, medical and religious institutions, and cultural groups. An ecologic model of development delineates the important dynamic process by which children and their environments interact.10,52 Occupational therapists view the child in the context of his or her social environments. With an increased focus on participation in everyday occupations, occupational therapists are incorporating evaluation measures that allow them to move beyond impairment-based measures to ecologic assessments that facilitate a better understanding of the child’s social and community participation.

FIGURE 7-1 Family environment: parents playing with their two children at the park. Courtesy Susan Phillips.

Coster, Deeney, Haltiwanger, and Haley, the authors of the School Function Assessment (SFA), provide an exemplary model of pediatric assessment.16 Coster and her colleagues recognized the need to develop an assessment tool that measures children’s ability to participate in the academic and social aspects of the school environment. The SFA fills an important gap for therapists and educators interested in using a top-down, problem-solving approach by first considering the student’s current level of participation in the educational programs and activities expected of his or her peers and then identifying the activity settings in which the student’s participation is less than expected. This instrument is based on key concepts of the ICF and is consistent with the OTFP.

Other measures of participation in childhood occupations are used by pediatric occupational therapists. The Activities Scale for Kids is a measure of a child’s self-report of activities done every day.58 The child describes what he “did do” and what he “could do” during the past week, to help determine the effect of the child’s physical disability on engagement in everyday occupations. The Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and the Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC) measure a child’s day-to-day participation in activities and the child’s preference for those activities.34 The CAPE is a 55-item questionnaire designed to examine how children and youth participate in everyday activities. The questionnaire provides information about the diversity, intensity, and enjoyment in five types of activities (recreational, active physical, social, skill-based, and self-improvement activities). The PAC contains the 55 activities also included in the CAPE. The PAC scores are average preference ratings for each of the five activity categories. The Miller Function & Participation Scales measure the child’s participation at school with an emphasis on fine motor, gross motor, and visual motor performance.45

An understanding of the child’s participation in everyday activities is gained by using multiple measures, over multiple times, in multiple settings. In addition to the measures described earlier, evaluation data are obtained through direct observation of the child and through interviews with the child, the child’s parents, and others who know the child.

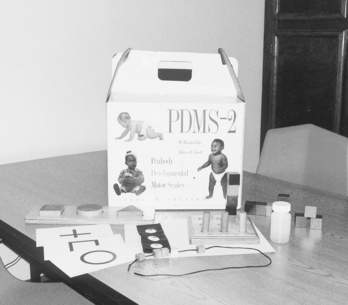

Interviews with parents and other adults working with the child are another primary source of data regarding the child’s performance and level of participation. For intervention planning, norm-referenced instruments may have limited value. Norm-referenced developmental assessments measure skills commonly seen in children who are typically developing, but they do not necessarily measure what is critical for functional performance in children with disabilities. For example, several of the items on the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales-2 (PDMS-2) (Figure 7-2) require the stacking of 1-inch cubes.23 Is this specific skill critical for the child’s success on everyday tasks? A common mistake of therapists is to design intervention goals directly from norm-referenced test items. This approach not only misses the mark with regard to writing functional outcomes, but may invalidate the use of these test items during reevaluation because of the practice effect on the child.

FIGURE 7-2 Fine motor materials from the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales-2 (PDMS-2) assessment tool.

Therapists use criterion-referenced and curriculum-based assessments when the primary evaluation purpose is treatment planning. These measures provide information about specific skills important to the child’s functional performance in activities of daily living, play, or school-related tasks. The Hawaii Early Learning Profile (HELP) is a curriculum-based assessment tool used to identify developmental needs and track progress in children from birth to 3 years of age.25 The Assessment, Evaluation and Programming Systems for Infants and Young Children (AEPS) (2nd ed.) is an activity-based system that links assessment, intervention, and evaluation for children from birth to 6 years.8 The Carolina Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers with Special Needs (3rd ed.) is an assessment and intervention program designed for use with young children from birth to 5 years who have mild to severe disabilities.32 The Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment (TPBA) (2nd ed.) measures the child’s cognitive, social-emotional, communication, and sensorimotor skills during a play session in a natural environment.40 The School Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (School AMPS) is an innovative observational assessment tool used by occupational therapists to measure the quality of a student’s performance on goal-directed tasks.22 The School AMPS addresses functional performance issues in the classroom and provides information for effective programs and consultation in the school setting. An observational tool that measures an important dimension of children’s play is the Test of Playfulness.53 This criterion-based tool examines the key elements of playfulness: intrinsic motivation, suspension of reality, and internal locus of control.

Application

Case Study 7-1 illustrates the application of the OTPF to the evaluation of a child with developmental delays and environmental risk factors.

Screening

The primary reason for screening children is to determine whether they warrant a more comprehensive evaluation. Occupational therapists may participate in two levels of screening. The first level is a basic screening of developmental skills (e.g., motor, social, language, personal and adaptive skills). In some settings, such as public school programs, occupational therapists may participate in the screening of large numbers of children to determine which children should receive further testing. Public policies and regulations, including the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA),30,31 Head Start, and Medicaid programs for children, mandate early developmental screening to identify children at risk for disabilities. Some examples of this first level of screening include the Ages & Stages Questionnaires,9 the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-Screening Test,7 the Denver Developmental Screening Test-II (Denver-II),24 and the FirstSTEP.43

More frequently, pediatric occupational therapists participate in the second level of child screening. This type of screening usually occurs after a health care professional or teacher identifies the child as being at risk for developmental delays or functional limitations. At this point in the screening process, the occupational therapist administers more comprehensive screening tools specific to a particular functional area of concern.

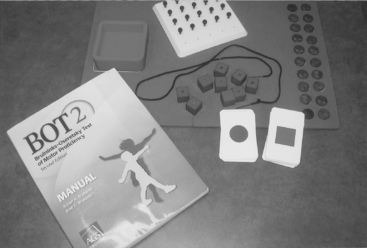

For example, second-level screening of a child might proceed as follows: A first grade teacher observes her student’s unusual responses to sensory experiences during art projects and his motor clumsiness on the playground at recess. The teacher refers the child to the occupational therapist for screening to determine if he needs a more comprehensive evaluation. In this case, the therapist might choose the Short Sensory Profile17 and the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOT-2) (Short Form)11 (Figure 7-5) to screen the child and determine the need for further evaluation.

In addition to administering standardized screening tests, the occupational therapist gathers pertinent information from parents and teachers and observes informally the child’s performance in his or her natural environments (e.g., classroom, playground, and home). Regardless of the setting and the level of screening, the therapist considers the following points when screening children to determine whether further evaluation is warranted:

1. Standardized screening tools are implemented whenever possible to ensure that the results of the screening are reliable and valid. Standardized tests require uniform procedures for administration and scoring. Chapter 8 provides more information on the use of standardized instruments.

2. In addition to standardized screening tools, the therapist gathers relevant information from the child and the child’s teachers, parents, or other caregivers (Figure 7-6).

3. Information gathered during the screening process includes the child’s performance across various developmental domains (e.g., motor, social, self-help) and in different environments to substantiate the need for further evaluation.

4. Screening tools are evaluated carefully for their cultural validity, and the results are interpreted cautiously when administered to children from diverse cultural backgrounds. A few instruments have established norms for children of different ethnic groups. For example, the Miller FirstSTEP43 is published in Spanish (Primer PASO),44 with norms established on 500 Spanish-speaking children.

Eligibility and Diagnostic Purposes

To determine children’s eligibility for services, standardized measures are used to ensure that the test results are reliable and valid. Common assessment tools that occupational therapists use with children and adolescents are listed in Appendix 7-A.

Many public school systems mandate the use of norm-referenced tests by school personnel when qualifying students for special services. For example, to qualify in the developmentally delayed category, children between 3 and 6 years of age in Washington State must perform at least two standard deviations below the mean on a standardized, norm-referenced test in one developmental area or 1.5 standard deviations below the mean in two developmental areas.55

Standardized, norm-referenced measures determine how the individual child’s performance compares with that of children in the normative sample. Because most norm-referenced instruments do not include children with disabilities in their standardization sample,21 the therapist must use caution when interpreting the performance of a child with a disability. For example, a child with Down syndrome may score more than two standard deviations below the mean for his or her chronologic age, but this standard score does not reveal how he or she performs relative to other children with Down syndrome.

The IDEA mandates that “any assessment and evaluation procedures and materials that are used are selected and administered so as not to be racially or culturally discriminatory” (§300.304).32 Unfortunately, many measures standardized on the U.S. population have limited cultural validity for children from ethnic groups not fully represented in the U.S. norms.

In summary, standardized, norm-referenced tools have an important, but limited, function in the occupational therapy evaluation process. Some service systems may require their use for determining a child’s eligibility. However, standard scores, when used alone, do not provide a complete picture of a child and may be misleading, particularly for children with established disabilities or those from diverse cultural or ethnic backgrounds.

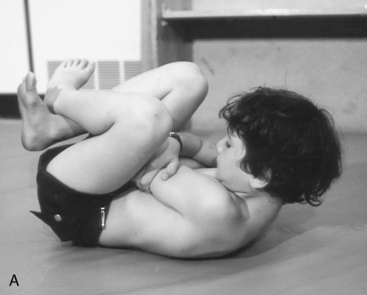

The occupational therapist also participates in multidisciplinary evaluations to determine a child’s diagnosis. To assist in the diagnostic process, the therapist considers a combination of standardized norm-referenced tools, caregiver interviews, and skilled observations. Skilled observations (Figure 7-7) are nonstandardized methods developed by therapists to gather objective data on the quality, frequency, and duration of the child’s performance. The “Evaluation Methods” section in this chapter presents specific information about the use of skilled observation. Box 7-1 provides a sample form for skilled observations of a child’s neuromotor status. Scores from a norm-referenced measure provide the basis for the child’s developmental status relative to other children the same age. In addition, the therapist’s skilled observations of a child’s performance provide important information on the quality of performance and possible reasons for the child’s delayed or poor performance on the norm-referenced test. Case Study 7-2 describes how norm-referenced measures are used in combination with nonstandardized, skilled observations.

Reevaluation Purposes

In the reevaluation of a child’s performance, progress is measured and the need for continued therapy is determined. The content and format of the reevaluation vary according to the specific purpose of the reevaluation. If the purpose is to determine whether the child continues to qualify for early intervention or special education services, the reevaluation may include a norm-referenced measure to ensure valid and reliable results. However, if the primary purpose of the reevaluation is to determine whether the child is making progress in therapy, criterion-referenced measures or the specific therapy goals and objectives are generally more appropriate and sensitive to the functional changes in the child.

For example, an infant with Down syndrome may show a drop in scores on a norm-referenced test over the course of the intervention year. However, these standard scores indicate only that the infant is developing at a slower rate compared with the test’s norms. Measures of progress more sensitive to the developmental changes seen in this infant may be the long-term goals and short-term objectives written by the early intervention therapist. Short-term objectives are developed by therapists through careful task analysis and lead sequentially to more advanced behaviors stated in the long-term, functional goals. When written as criterion-referenced, measurable behaviors, short-term objectives can be used to evaluate the child’s progress toward the long-term goal.

The process of reevaluation of children is ongoing and dynamic. Each time a therapist works with a child, the therapist evaluates the child’s response to the therapeutic activities and assesses the child’s performance on functional tasks. The therapist analyzes and interprets the data gathered during each therapy session to determine whether the intervention plan needs adjustment. In summary, although a formal reevaluation of the child is conducted at specific times during the course of therapy services, the occupational therapist embeds evaluation probes within each therapy session.

Clinical Research

Occupational therapy researchers carefully select standardized measures to evaluate the child’s performance and participation in everyday activities. A more complete discussion of standardized tests used for clinical research is presented in Chapter 8, but a few major points are offered here:

1. Whether the research design includes a large group of children or a single subject, the instruments used must be reliable and valid measures of the dependent variable.

2. The measures selected depend on the research design. Standardized, norm-referenced, or criterion-referenced instruments are used in large-group designs. Occupational therapists working in rehabilitation settings use the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM) to document clinical outcomes related to children’s self-care, mobility, communication, and social problem solving.27 Criterion-referenced instruments or operationally defined therapy objectives are used for single-subject research.

3. An important area of research in pediatric occupational therapy is the measurement of outcomes to document treatment effectiveness. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) is a technique used to evaluate the functional goal attainment of children receiving therapy.35 GAS is an individualized, criterion-referenced measure of change that has been used to assess occupational therapy outcomes for children with learning disabilities,57 children with traumatic brain injury,47 and children with sensory integration disorders.41

Examples of research instruments include the tools that have been developed by Kielhofner and his colleagues to measure occupation based on the Model of Human Occupation. These instruments assess a child’s volition, providing specific information about the child’s interests and values. The Pediatric Volitional Questionnaire obtains information about the child’s motivation, values, and interests.6 The Child Occupational Self Assessment (COSA) is a self-report in which the child rates his performance competency and the importance of the skill.33 By objectively quantifying information that occupational therapists typically obtain through informal interview, interest and motivation can be used as variables in research studies.

Law used an earlier version of the ICF56 as a framework to develop a computerized, self-directed software program designed to help pediatric therapists select relevant and appropriate outcome measures for client, service, or program evaluation.38 With a large database of pediatric measures, this software program is an excellent resource for practitioners and researchers in occupational therapy who are conducting clinical outcome studies on children with disabilities.

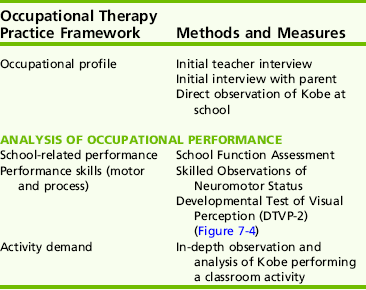

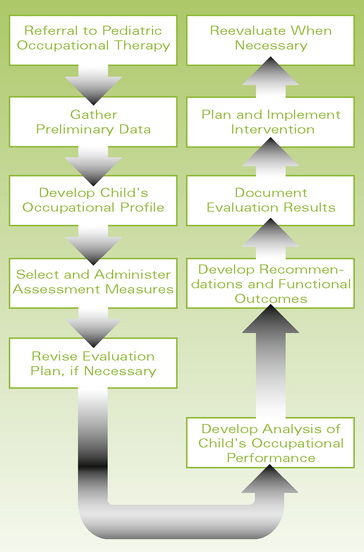

EVALUATION PROCESS

This section provides a logical sequence of steps that pediatric occupational therapists follow in the process of evaluating children. Kobe’s case, discussed previously, is a good illustration of the evaluation process. Based on Kobevs occupational profile, the therapist identifies several methods and measures to evaluate Kobe’s occupational performance. Not all the methods and measures listed in Table 7-1 need to be completed before occupational therapy can commence for Kobe. The process of evaluation in occupational therapy starts with the referral and continues for the duration of therapy services. Key areas of the child’s performance are evaluated before the intervention plan is developed and therapy is initiated. Other areas of evaluation are completed as the therapist learns more about the child and family. The therapist, therefore, continually considers the new challenges the child faces and other priorities that emerge for the family.

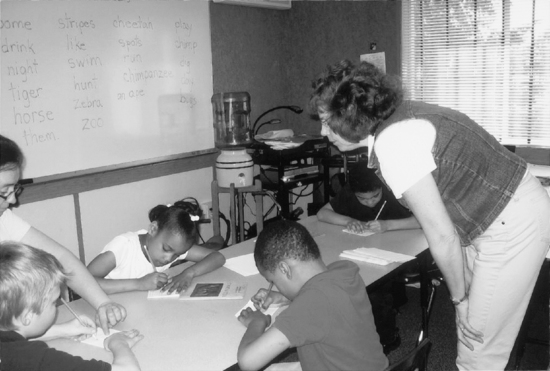

According to the Standards of Practice for Occupational Therapy,2 the occupational therapist and the occupational therapy assistant have important but different roles in the evaluation of clients. The occupational therapist is responsible for selecting evaluation methods and measures and interpreting and analyzing assessment data. The occupational therapy assistant, under the supervision of the occupational therapist, may contribute to the child’s evaluation by administering some of the assessments and documenting some of the results (Figure 7-9).

FIGURE 7-9 Occupational therapy assistant evaluating children’s performance during a handwriting activity school.

To conduct thorough evaluations and provide accurate interpretation and documentation of evaluation results, occupational therapists follow logical steps in the evaluation process. Figure 7-10 shows a flowchart for the evaluation sequence.

Referral

Children who have or are at risk for disabilities are referred to occupational therapists by health care providers, educators, and other professionals for evaluation of and intervention for occupational performance deficits. The referral form often lists the child’s diagnosis or deficits in specific developmental areas. To ensure that the referrals to occupational therapy are appropriate, the occupational therapist should be involved in the development of the referral form used in his or her work setting.

Development of the Child’s Occupational Profile

Once the therapist receives the referral, he or she consults with the child’s parents and professionals from other disciplines to determine which measures to use, the evaluation setting, and the schedule for the occupational therapy evaluation activities. Most therapists find it helpful to formulate an evaluation plan based on the childs chronologic age, presenting problems, theoretical frames of reference, parents’ priorities regarding reasons for referral, availability of evaluation tools, type of service delivery model, and amount of time and resources available for initial evaluation activities. The therapist lists the major concerns and the evaluation methods and measures that specifically assess those concerns (Table 7-2). Box 7-2 provides a checklist of the important steps therapists take in the process of selecting appropriate methods and measures when evaluating children.

Kramer and Hinojosa described how philosophical foundations and theoretical frames of reference guide the occupational therapist in the selection, use, and interpretation of assessment measures.37 Kobe’s case (Case Study 7-3) illustrates the application of theory to the evaluation process. As mentioned previously, the therapist hypothesized, on the basis of Kobe’s occupational profile, that his performance deficits are likely a result of his significant motor challenges, possible visual processing deficits, and some environmental barriers. In this case, the therapist draws on specific models of practice (e.g., client-centered approach, person-environment-occupation model, compensatory approach, motor learning theory) to select methods and measures for Kobe’s evaluation.

As mentioned previously, the evaluation process occurs over time. In view of the complexity of problems in children referred to pediatric occupational therapists, it may be difficult to formulate a comprehensive evaluation plan based on the limited referral information. Therefore, the therapist usually revises the evaluation plan when more information is obtained regarding the family’s priorities and the child’s functional status. In Kobe’s example, the therapist learned from a phone interview with the mother that she is most concerned about his safety while driving his powered wheelchair.

Administration of Evaluation

Using key information from the child’s occupational profile, the therapist decides which methods and measures to administer to evaluate more fully the child’s performance skills and the contexts that may be limiting his or her participation in everyday occupations. In Kobe’s case, the therapist selects a series of methods and measures to evaluate his performance at school, his neuromotor status, and his visual processing skills. Although data from these methods and measures provide an initial picture of Kobe, the therapist recommends further assessment of his computer skills and his preferences related to school and home activities.

For most entry-level therapists in pediatrics, one of the most challenging aspects of the evaluation process is managing the child’s behavior during administration of the evaluation measures, particularly when the measures are more formal, structured, and standardized. The evaluation of infants and young children in a structured situation is demanding for the children, the parents, and the therapist. Box 7-3 outlines several strategies therapists can use to manage young children’s behavior during structured, standardized assessments.

The administration of nonstandardized tools, skilled observations, environmental assessments, and interviews with the child’s caregivers should receive the same careful attention and preparation by the occupational therapist as the standardized measures require. For some children, a combination of standardized tests and nonstandardized measures is appropriate, but for many children with severe disabilities, norm-referenced tests are neither valid nor meaningful. In these cases, data gathered from criterion-referenced and nonstandardized measures provide the essential information for planning intervention.

Analysis of the Child’s Occupational Performance

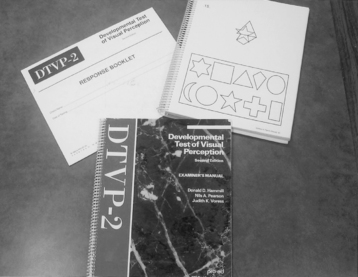

After most of the evaluation information on a child’s performance and participation is gathered, the therapist analyzes the quantitative and qualitative data from the various methods and measures used. When a standardized test is used, the therapist carefully follows procedures outlined in the test manual to interpret accurately the test results. When nonstandardized measures are used, the therapist skillfully identifies any patterns of strength and areas of concern across all measures. Often data obtained from nonstandardized measures are instrumental in identifying the possible underlying reasons for a child’s specific performance on standardized tests. To illustrate this point, consider Kobe’s case. His teacher wondered if he had visual perceptual deficits that affected his performance on school-related tasks. Although Kobe scored significantly better on the visual-perceptual test items than on the visual-motor test items, other observations of his performance across school settings (e.g., classroom, lunchroom, and playground) revealed his difficulties with figure-ground perception. For example, he had a difficult time finding letters on a busy worksheet, locating his spoon on a crowded tray, and finding his way through a maze of children in the hallway (see Case Study 7-3).

Accurate and complete interpretation of all accumulated data is an important and demanding task in the evaluation process. The occupational therapist must be thorough in examining the details of a child’s performance and viewing the child’s behaviors in the context of environmental demands and supports. Accurate and complete interpretation of evaluation data allows therapists to make sound clinical decisions, including whether the child would benefit from occupational therapy services and, if so, the appropriate frequency, duration, and type of therapeutic intervention. Once the evaluation data are analyzed, the therapist turns to the task of developing recommendations for the child.

Development of Recommendations Based on Evaluation Results

One of the first factors the therapist considers when developing recommendations is the functionality of the recommendations. The term functionality refers to the relevance of the recommendation to the child’s daily life.49 When developing recommendations for a child, the occupational therapist asks the following two questions:

1. Does this recommendation relate to the child’s occupational performance?

2. Is this recommendation relevant to the child’s participation in everyday activities?

Writing therapy goals and objectives gives therapists the opportunity to think about and determine the most important skills a child needs to meet the demands of his or her environment(s). Bundy suggests that functional outcomes for children be viewed as an expression of possibilities of what children can do with support from their families and therapists.12 The following examples illustrate how therapists can translate evaluation findings into functional, measurable treatment goals that are relevant to the everyday activities of children.

1. Evaluation finding. Because of imprecise release of objects, Jill does not stack 1-inch cubes on the PDMS-2.

2. Evaluation finding. Because of increased muscle tone and poor reciprocal movements in the lower extremities, Ryan does not assume the half-kneel position on either leg when coming to stand, an item on the Gross Motor Function Measure (2nd ed.) (GMFM-II).51

A second factor to consider when making recommendations is the parents’ or teachers’ priorities for the child. Hanft suggests that every recommendation from an occupational therapist to a parent of a child with special needs should be followed by a question to the caregiver29: “How will this suggestion work for you and your child?” For example, during a feeding evaluation in a child’s home, a therapist observes a mother and her child who has cerebral palsy and failure to thrive. The therapist notes that the mother placed the child in an infant walker at mealtime. Because infant walkers are unsafe and because this particular child would benefit from a more stable seating device that provides trunk and head support for optimal oral-motor performance, the therapist recommends the use of the infant walker be discontinued and a special feeding seat be ordered. However, unless the therapist asks the mother what the implications of this recommendation are for her child and family, the mother may not implement this important recommendation. In this case, additional information from the mother revealed that the child refused to eat in any other position than in the walker. She was more concerned about her child’s adequate nutrition for growth than his feeding position. Based on the mother’s input, the therapist provided the parents with information on the safety of infant walkers and the importance of proper positioning when swallowing to prevent aspiration.

A third factor for therapists to consider when developing recommendations from evaluation findings is the service delivery model. Dunn defined service delivery models as direct services, integrated or supervised therapy, and consultation.19 The therapist’s recommendations should be consistent with the program’s service delivery model. For example, if the therapist’s primary role with the child is consultation, recommendations from the initial evaluation center on how to teach the parents and other adults working with the child to adapt the child’s environment.

The therapist must be able to reconcile these three, sometimes conflicting factors when developing meaningful recommendations for children. Years of experience can teach a therapist to negotiate through the maze of issues regarding the child, family, team, environments, and service delivery systems. Entry-level therapists, however, can use several basic strategies to help them become more competent in evaluating children:

1. Find a mentor who is experienced in working with children with various diagnoses and families from diverse backgrounds.

2. Be willing to search continually for new knowledge and resources that are relevant in working with children with special needs.

3. Be open to new ways of viewing children and families.

4. Learn to build effective communication and collaboration skills with team members, including the child’s parent.

Documentation of Evaluation Results and Recommendations

The next step in the evaluation process is to provide written and oral reports on the evaluation findings and recommendations. The primary purpose of documenting the results of the pediatric occupational therapy evaluation is to describe to individuals working with the child the child’s current abilities and limitations on various functional tasks. McClain suggested: “Effective documentation is telling a true story with a particular style. It calls for the ordinary tasks of day-to-day experience to be succinctly stated in writing. The true story about any child who has a disability is not a simple tale” (p. 213).42

When providing written documentation, the therapist must first consider for whom the reports are intended, then carefully construct reports that are understandable and useful to those individuals. The format and content of evaluation reports may vary significantly, depending on the referral concern, the complexity of the child’s problem, and the regulations of the service delivery system in which the child is served (e.g., public school setting, hospital, or outpatient clinic). For eligibility purposes, written evaluation reports usually include specific standard scores documenting developmental delay. In all pediatric occupational therapy settings, documentation creates a chronological record of the child’s status, the occupational therapy services provided to the child, and the child’s outcomes.3

Experienced therapists recognize that their words have significant impact on the child’s family. Hanft cautioned pediatric therapists that “words convey powerful personal images that can be positive and supportive or negative and destructive” (p. 5).28 Pediatric occupational therapists should use words that reflect positive attitudes toward children with disabilities. Unfortunately, some therapy reports include jargon or technical terms that may not convey the intended message and often confuse or alienate parents. Therapists should use “person first” language in their documentation (e.g., a child with cerebral palsy; not a cerebral-palsied child).

Case Study 7-3 provides a written example of how the therapist documents Kobe’s evaluation findings and recommendations. An important point is that the therapist words the report so that the information is helpful to Kobe’s parents and teacher. The format and terminology of the evaluation report are consistent with the OTPF.1

In summary, to ensure the evaluation process provides a family-centered, occupation-based approach using valid and reliable measures, occupational therapists should ask the following questions:

1. Are the caregiver’s concerns about the child addressed?

2. Does the evaluation measure the child’s engagement in occupations and activities and identify the factors that support and hinder the child’s participation?

3. Are multiple methods of evaluation used, including interviews, direct observations of the child in the natural environment, and standardized tools?

4. Is the child’s cultural background considered in selecting evaluation methods and measures and in developing recommendations for intervention?

5. Are administration procedures correctly applied in using standardized tests?

6. Are the child’s strengths and interests documented?

7. Does the evaluation report contribute meaningful, user-friendly information about the child’s functional skills?

This section described the evaluation process, including important sequential steps for conducting accurate, thorough evaluations of children and documenting the evaluation findings to parents and other professionals working with the child.

EVALUATION METHODS

Several evaluation methods are available to occupational therapists. The challenge for therapists is to determine which evaluation methods to select for a particular child or group of children. This section describes the primary evaluation methods commonly used in pediatric occupational therapy practice and discusses the major factors that therapists consider when selecting a particular method.

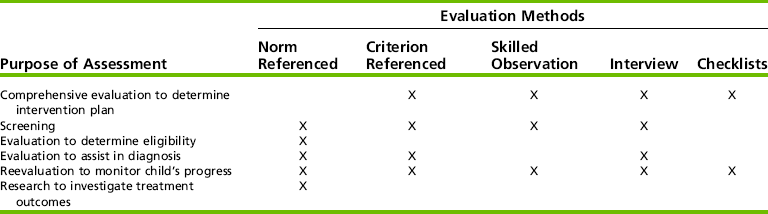

The starting point in the selection process is to identify clearly the purpose of the evaluation and to match appropriate evaluation methods with the identified purpose. For example, if the only purpose of the evaluation is to determine a child’s eligibility for special education services in a public school setting, the primary evaluation method is a norm-referenced, standardized test. If the primary purpose of the evaluation is to gain information useful for planning an intervention program for the child, the evaluation measures include skilled observations of the child’s functional performance and interviews with the child’s caregivers. Often the initial evaluation of a child serves more than one purpose; therefore, therapists frequently use multiple measures and methods when conducting child evaluations.

Standardized Assessments

Norm-referenced measures are tests based on norms of a sample that represent the population to be tested. The child’s score on a norm-referenced test is compared with the scores of the normative sample. To evaluate the usefulness of a norm-referenced measure, the pediatric occupational therapist reads the test manual carefully to learn about the characteristics of the normative sample, how the norms were derived, and how to interpret accurately an individual childs scores.

Criterion-referenced measures are standardized tests that consist of a series of skills on functional or developmental tasks, usually grouped by age level or performance area. These tests compare the child’s performance on each test item with a criterion that must be met if the child is to receive credit for that item. The items on a criterion-referenced test are selected because of their importance to the child’s function on everyday tasks. Therefore, the items often become intervention targets when the child exhibits difficulty in successfully completing them.

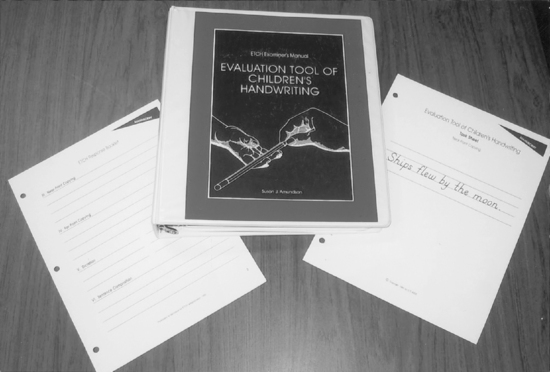

Some examples of criterion-referenced measures used by occupational therapists are the Hawaii Early Learning Profile Checklist,25 the revised Erhardt Developmental Prehension Assessment,20 the Assessment and Programming System for Infants and Young Children (2nd ed.),8 and the Evaluation of Children’s Handwriting (ETCH) (Figure 7-11).4 Informationgained from criterion-referenced tests is particularly helpful for evaluation of the child’s functional skills and for planning appropriate intervention activities to enhance those skills (see Appendix 7-A).

Ecologic Assessments

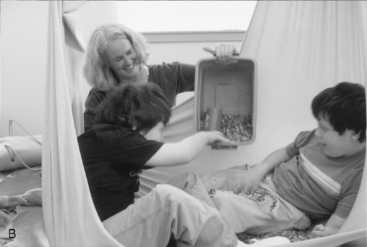

Neisworth and Bagnato defined ecologic assessments as “the examination and recording of the physical, social, and psychological features of a child’s developmental context.”48 Consistent with the transactional approach,52 ecologic assessments are also concerned with the interaction between the child and his or her physical and social environments (Figure 7-12).

FIGURE 7-12 A, Observation of child in his natural environment. B, Observation of peer interaction during play.

Occupational therapists are particularly interested in ecologic measures because these tools are a primary mechanism for obtaining data relevant to the child’s performance context. An ecologic assessment of a child uses techniques that consider the cultural influences, socioeconomic status, and value system of the family. These assessments also consider the physical demands and social expectations of the child’s environment. Some of these methods include naturalistic observations, interviews, and rating scales. Ecologic measures that are often administered by occupational therapists include the Knox Preschool Play Scale,36 the revised HOME Inventory,13 and the TPBA40 The SFA is another example of an ecologic assessment.16 The Sensory Processing Measure provides a comprehensive measure of children’s sensory functioning in the context of their occupational performance and roles in the home, school, and community.46,50

Skilled Observation

An essential skill of the pediatric occupational therapist is the ability to observe keenly and to record accurately children’s behavior in an objective manner. Although formal, standardized assessments are highly valued in pediatric practice, skilled observation of a child performing a functional task offers different but equally important information about the child’s performance (Figure 7-13).

Dunn proposed that skilled observation is one of the essential tools available to occupational therapists.18 Dunn described the following key competencies required to conduct skilled observations: (1) do not interfere with the natural course of events, (2) pay attention to the physical and social features of the environment that support or limit a child’s performance, and (3) record the child’s behavior in observable and neutral terms. When skilled observations are used in the evaluation process, therapists must select a systematic, objective recording procedure so that data collected are accurate and reliable. Clark and Miller proposed a problem-solving approach to functional assessments and data-based decision making for occupational therapists working with children in school settings.14 Based on direct observations of the child’s performance at school, the occupational therapist and other team members define the outcome behaviors and design a useful data collection system to monitor the child’s progress.

A word of caution is due, however, about the use of skilled observations of the child in his or her natural environments. If the examiner is not experienced in observing children, he or she may not recognize key behaviors or patterns of behavior in the child and the meaning of those behaviors within the demands of the task and the environment. Therapists entering the field of pediatric occupational therapy should seek out master clinicians and mentors who are willing to help new therapists hone their observation skills.

Interviews

Another primary method used in pediatric occupational therapy evaluation is the interview with the child, the child’s parent, the teacher, and other adults working with the child.

Interviews used in conjunction with other evaluation methods provide a more comprehensive view of the child. An important outcome of the interview is an accurate, meaningful exchange of information between the professional and the client (e.g., parent, older child, or adolescent). When done well, interviews can provide an opportunity for building rapport between the therapist and the client. They provide a unique opportunity for parents, children, and adolescents to identify and discuss issues that are important to them. Interviews, therefore, are particularly useful when the therapist is interested in individuals’ perceptions of their own abilities, the influence of specific events on them, and their priorities for intervention. When interviews are conducted in a flexible, sensitive manner, therapists and clients are able to explore areas of concern as they arise.

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is a well-researched tool that uses a structured interview format to obtain information on the client’s performance and satisfaction in the areas of self-care, leisure, and productivity.39 This tool was designed to help occupational therapists identify the targets for intervention based on the individual’s most important concerns. The COPM manual discusses some cautions and considerations when interviewing children. The authors suggest “that even as young as 5 or 6 years, children can tell us what they are having trouble with and what they are willing to work on” (p. 39).39 When the child is very young or not capable of expressing his or her thoughts, parents are interviewed to gain their perspectives and concerns related to raising their child.

Interviews may include closed- or open-ended questions or a combination of these. Specific questions, which are often closed-ended, allow the therapist to gather a predetermined set of information from the individual in a relatively short time. Unstructured interviews using open-ended questions allow the child or parent to take the lead and set the priorities in the discussion. Open-ended questions invite the individual to elaborate on a topic and provide critical information (Box 7-4). An important decision the therapist makes when conducting interviews with parents is whether the interview is done in the presence of the child. Most parents are uncomfortable describing their child’s deficits in front of the child, particularly if the child is older than 3 years of age and possibly aware of his or her difficulties. Therapists and parents should carefully plan when, how, and where to conduct the interview(s).

In summary, a skilled therapist interviews children (older than 5 or 6 years) and caregivers by carefully selecting questions and sensitively listening to the responses. Interviews offer a unique opportunity for an exchange of information between the child or adolescent, the parents or teacher, and the therapist. During the interview, the therapist should reciprocate by providing accurate, relevant information about the functional abilities of the child or adolescent, the intervention services, and community resources.

Inventories and Scales

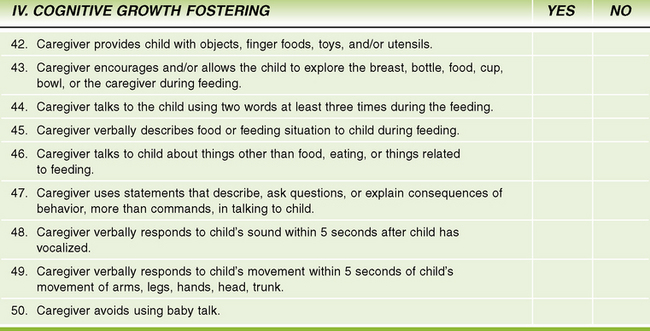

A variety of inventories and scales are used to gather data on a child’s development, on caregiver–child interactions, or on the child’s environments.

The Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI) is an evaluation of functional capabilities and performance in children 6 months to 7.5 years of age.26 The PEDI is judgment-based inventory completed by the parent and professionals who are familiar with the child. It measures both capability and performance of the child during functional activities (e.g., self-care, mobility, and social function). The inventory consists of 197 functional skills items; the child is scored either 1 (has capability) or 0 (has not yet demonstrated capability, unable) on each item. Twenty additional items rate the amount of caregiver assistance required to complete key functional tasks. The PEDI was designed for use with young children who have a variety of disabling conditions, particularly physical disabilities. The authors completed a series of reliability and validity studies and developed criterion scores using Rasch analysis techniques. As a result, the PEDI stands as a well-developed instrument for evaluating the functional performance and capabilities of children.

A rating scale may rate the quality, degree, or frequency of a behavior. (For example, the Caregiver/Parent–Child Interaction Feeding and Teaching Scales are designed to assess parent–child interactions in the context of feeding and teaching events).54 Figure 7-14 shows the type of data obtained using the feeding scale’s rating system.

A parent, teacher, or other caregiver can complete some inventories and rating scales. For example, the Ages & Stages Questionnaires rely exclusively on parent report.9 On this scale, the items are clearly described, and many are illustrated so that parents can record specific behaviors of their children. After each item, parents check the appropriate box—“yes,” “sometimes,” or “not yet.” The Sensory Profile17 and the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile19 are caregiver questionnaires that may be completed through a parent interview.

Arena Assessments

In many settings serving children with disabilities, a team of professionals evaluates the child. The form and scope of team evaluations vary widely, depending on the philosophy of the intervention program and the expertise of the professionals. For example, in some settings, each professional provides an individual evaluation of the child, then the team members meet to discuss their evaluation findings and recommendations. Sometimes little or no communication occurs among team members before or during the evaluation. In contrast, a team in another setting may use the transdisciplinary approach, in which one primary team member conducts the evaluation while other key team members contribute their expertise to the evaluation process through consultation.

The arena assessment uses a transdisciplinary approach that allows the child and primary caregiver to interact with one professional throughout the evaluation session while other professionals observe and, on occasion, directly test the child or interview the caregiver. An example of an arena assessment is the TPBA.40 This assessment places major emphasis on a team approach to the evaluation of young children. The purpose of the TPBA is to obtain developmental information on the child using multidimensional, functional observations of the child during a play session. Parents and professionals together plan, observe, and analyze the child’s play session.

Arena assessment of feeding difficulties in children is an effective way to gather relevant information without over-testing the child or requiring the caregiver to participate in repeated interviews with different professionals. For example, an arena feeding assessment for a child with cerebral palsy and failure to thrive may include an occupational therapist, a nurse, a psychologist, and a nutritionist. One professional is designated the lead evaluator, depending on the primary referral concern. The occupational therapist may take the lead if the child has oral-motor deficits, such as chewing or swallowing difficulties, postural difficulties that create the need for external support of posture at mealtime, or fine motor difficulties that limit self-feeding skills. The nurse or the psychologist may take the lead in the evaluation process if the child exhibits behavioral difficulties, if the parent’s caregiving skills appear limited, or if parent–child interactions are at risk. The nutritionist may take the lead if the child’s diet needs careful analysis and if the family would benefit from specific information on types and amounts of food the child should eat. The benefit of an arena feeding assessment is that the child and the caregiver are subjected to the mealtime evaluation only once, rather than several times. The arena assessment provides an opportunity for collaboration among parents and professionals to observe, discuss, and solve problems in critical areas together.

SUMMARY

Accurate, reliable evaluation of a child is one of the most challenging and rewarding services an occupational therapist offers. This chapter described the purposes, processes, and methods of evaluation in pediatric occupational therapy. Having an awareness of the many purposes of evaluation and the ability to match carefully appropriate methods and measures with those purposes are critical skills of the pediatric occupational therapist. Careful observation of the details of a childs performance on tasks and recognition of the importance of the context in which the child performs those tasks are also essential to skillful evaluation. Equally important in the evaluation process is the therapist’s collaborative skills when working with the child’s caregiver and other team members to gain an in-depth understanding of the child and his or her environments. A comprehensive view of the child’s participation in settings and activities important to the child and family leads to the development of relevant, appropriate occupational therapy interventions.

REFERENCES

1. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;62(6):625–683.

2. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Standards of practice for occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005;59:663–665.

3. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), (6). Guidelines for documentation of occupational therapy, 2008;62:684–690. American Journal of Occupational Therapy.

4. Amundson, S., Evaluation of children’s handwriting. Homer A.K., ed. OT kids, 1995, http://psychtest.com/.

5. Ayres, A.J. Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1989.

6. Basu, S., Kafkes, A., Geist, R., Kielhofner, G. The Pediatric Volitional Questionnaire (PVQ) (2.0). Chicago: Model of Human Occupation Clearinghouse, Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois, 2002.

7. Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, 2005.

8. Bricker D., ed. Assessment, evaluation, and programming system, (2nd ed.), Baltimore: Brookes, 2002.

9. Bricker, D., Squires, J. Ages & stages questionnaires: A parent-completed, child-monitoring system, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes, 1999.

10. Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32:513–531.

11. Bruininks, R., Bruininks, B. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOT-2). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, 2005.

12. Bundy, A. Writing functional goals for evaluation. In: Royeen C.B., ed. AOTA self-study series: School-based practice for related services. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association; 1991:7–30.

13. Caldwell, B.M., Bradley, R.H. Home observation for measurement of the environment (rev. ed.). Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas, 1984.

14. Clark, G.F., Miller, L.E. Providing effective occupational therapy services: Data-based decision making in school-based practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996;50(9):701–708.

15. Coster, W. Occupational-centered assessment of children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;52(5):337–344.

16. Coster, W., Deeney, T., Haltiwanger, J., Haley, S. School Function Assessment. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 1998.

17. Dunn, W. Sensory Profile: User’s manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1999.

18. Dunn W., ed. Best practice occupational therapy in community service with children and families. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 2000.

19. Dunn, W. Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile: User’s manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 2002.

20. Erhardt, R.P. Erhardt Developmental Prehension Assessment (revised). Maplewood, MN: Erhardt Developmental Publications, 1994.

21. Farran, D.C. Another decade of intervention for children who are low income or disabled: What do we know now. In: Shonkoff J.P., Meisels S.J., eds. Handbook of early childhood intervention. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000:510–548.

22. Fisher, A.G., Bryze, K., Hume, V., Griswold, L.A. School AMPS: School version of the assessment of motor and process skills, 2nd ed. Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press, 2005.

23. Folio, M.R., Fewell, R.R. Peabody Developmental Motor Scales, 2nd ed. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed, 2000.

24. Frankenburg, W., Dodds, J. Denver Developmental Screening Test-II. Denver: Denver Developmental Materials, 1992.

25. Furuno, S., O’Reilly, K., Hosaka, C.M., Zeisloft, B., Allman, T. The Hawaii Early Learning Profile. Palo Alto, CA: VORT, 2004.

26. Haley, S.M., Coster, W.J., Ludlow, L.H., Haltiwanger, M.A., Andrellos, P.J. Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1992.

27. Hamilton, B.B., Granger, C.U. Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM). Buffalo, NY: Research Foundation of the State University of New York, 1991.

28. Hanft, B. How words create images. In: Hanft B., ed. Family-centered care: An early intervention resource manual. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association; 1989:77–78. [Unit 2].

29. Hanft, B. The good parent: A label by any other name would not smell as sweet. AOTA’s Developmental Disabilities Special Interest Section Newsletter. 1994;17(2):5.

30. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1997, 1997. [(Public Law 105-17) 20 USC 1400 et seq].

31. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, 2004. [(Public Law 108-446). 20 USC 1400 et seq].

32. Johnson-Martin, N.M., Jens, K.G., Attermeier, S.M., Hacker, B.J. The Carolina Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers with Special Needs, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes, 2004.

33. Keller, J., Kafkas, A., Basu, S., Federico, J., Kielhofner, G. Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA), Version 2.1. Chicago: Model of Human Occupation Clearinghouse, Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois, 2005.

34. King, G., Law, M., King, S., Hurley, P., Rosenbaum, P., Hanna, S., et al. Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, 2005.

35. King, G.A., McDougall, J., Palisano, R.J., Gritzan, J., Tucker, M. Goal attainment scaling: Its use in evaluating pediatric therapy programs. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 1999;19(2):31–52.

36. Knox, S. Development and current use of the Knox Preschool Play Scale. In: Parham L.D., Fazio L.S., eds. Play in occupational therapy for children. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008:55–70.

37. Kramer, P., Hinojosa, J. Theoretical basis of evaluation. In: Hinojosa J., Kramer P., eds. Occupational therapy evaluation: Obtaining and interpreting data. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc; 1998:17–28.

38. Law, M.C. All about outcomes: An educational program to help you understand, evaluate, and choose pediatric outcome measures (CD-ROM). Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1999.

39. Law, M.C., Baptiste, S., McColl, M., Carswell, A., Polatajko, H., Pollock, N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, 4th ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy Publications, 2005.

40. Linder, T.W. Transdisciplinary play-based assessment: a functional approach to working with young children. Baltimore: Brookes, 2008.

41. Mailloux, A., May-Benson, T.A., Summers, C.A., Miller, L.J., Brett-Green, B., Burke, J.P., et al. Goal attainment scaling as a measure of meaningful outcomes for children with sensory integration disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61(2):254–259.

42. McClain, L.H. Documentation. In: Dunn W., ed. Pediatric occupational therapy: Facilitating effective service provision. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1991:213–244.

43. Miller, L.J. First STEp Screening Tool. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1993.

44. Miller, L.J. Primer PASO Screening Tool. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 2003.

45. Miller, L.J. Miller Function & Participation Scales. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 2006.

46. Miller-Kuhaneck, H., Henry, D.A., Glennon, T.J. Sensory Processing Measure (Main Classroom and School Environments Forms). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 2007.

47. Mitchell, T., Cusik, A. Evaluation of a client-centred paediatric rehabilitation programme using goal attainment scaling. Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;45(1):7–17.

48. Neisworth, J.T., Bagnato, S.J. Assessment in early childhood special education: A typology of dependent measures. In: Odom S.L., Karnes M.B., eds. Early intervention for infants and children with handicaps: An empirical base. Baltimore: Brookes; 1988:23–49.

49. Notari, A., Bricker, D. The utility of a curriculum-based assessment instrument in the development of individualized education plans for infants and young children. Journal of Early Intervention. 1990;14:117–132.

50. Parham, D., Ecker, C. Sensory processing measure (Home Form). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 2007.

51. Russell, D.J., Rosenbaum, P.L., Avery, L., Lane, M. Gross motor function measure, Malden, MA, Blackwell Publishing, 2002. User’s manual.

52. Sameroff, A.J., Fiese, B.H. Transactional regulation: The developmental ecology of early intervention. In: Shonkoff J.P., Meisels S.J., eds. Handbook of early childhood intervention. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000:135–159.

53. Skard, G., Bundy, A. Test of playfulness. In: Parham L.D., Fazio L.S., eds. Play in occupational therapy for children. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008:71–94.

54. Sumner, G., Spietz, A. NCAST caregiver/parent-child interaction scales. Seattle: NCAST Publications, University of Washington, School of Nursing, 1994.

55. Washington [State] Administrative Code. Rules for the provision of special education: Eligibility criteria for students with disabilities (WAC 392–172–114). Olympia, WA: Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, 1998.

56. World Health Organization. ICF: International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

57. Young, A., Chesson, R. Goal attainment scaling as a method of measuring clinical outcomes for children with learning disabilities. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1997;60(3):111–114.

58. Young, N.L. Activities Scale for Kids. Toronto, ON: Pediatric Outcomes Research Team, Hospital for Sick Children, 1997.

CASE STUDY 7-1

CASE STUDY 7-1