INTERVENTIONS FOR CHILDREN WITH SENSORY INTEGRATIVE PROBLEMS

Planning an occupational therapy program for a child with a sensory integrative problem requires the same careful analysis used in applying any theoretical framework in clinical practice. The constellation of child and family characteristics is analyzed in relation to the occupations of the individuals involved. Intervention is designed to focus on engagement in occupation in order to support the participation of the child in the everyday contexts of his or her life.1 When a sensory integration approach is used in occupational therapy, the unique ways in which sensory integrative problems affect engagement and participation in the occupations of the particular child and his or her family provide the cornerstone upon which decisions regarding treatment are made.127 Intervention is continually planned and evaluated in relation to the occupations that the child wants and needs to do in the contexts of home, school, and community.

The assessment process helps the therapist decide whether any intervention is recommended and, if so, in what format: individual therapy, group sessions, or collaborative consultation with parents and teachers. Regardless of the form in which intervention is delivered, theory-based concepts regarding the nature of sensory integration are applied whenever a sensory integration approach is selected. Guiding principles of the ASI approach are summarized in Box 11-2.11,18,19 The key ideas behind these principles were introduced previously in this chapter in the sections on sensory integrative development and problems.

Therapists who plan interventions for children with sensory integrative problems are responsible for developing their professional expertise through advanced training, mentorship, and review of the research literature. The field of sensory integration is a complex, specialized area of occupational therapy practice that demands that the therapist synthesize information from many sources. Because it is a dynamically changing field of practice, it is important that the therapist stay abreast of research evidence, as well as of new developments in sensory integration theory and practice, to guide practice decisions. These sources of information, in combination with the unique situation of the child and family being helped, all influence the decision of whether to intervene and, if so, how.

In this section, four of the primary methods of occupational therapy intervention for children with sensory integrative problems are described: (1) individual ASI intervention to improve underlying sensory integration abilities, (2) individual skill development training, (3) group skill development intervention, and (4) consultation, including modifications of activities, routines, and environments at home and in school. These forms of intervention are often used in combination with each other, rather than as the sole service delivery method. With careful consideration on the part of the therapist, interventions based on other theoretical frameworks and treatment models may be used along with those discussed in the following sections of this chapter. The therapist must be mindful that if the intervention strategies being combined are not compatible owing to contradictory underlying principles, intervention effectiveness may be reduced. Therefore, although selection of a combination of intervention approaches is often desirable, it must be done with care.

Individual Ayres Sensory Integration® (ASI) Intervention

Individual occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration® (ASI) intervention is the most intensive form of occupational therapy available for children with sensory integration problems. The term Ayres Sensory Integration® (ASI) was trademarked by the Franklin B. Baker/J. Jean Ayres Baker Trust, “for the purpose of protecting and promoting Dr. Ayres’ body of work and to assist in differentiation of this approach from others that might share some similar terminology or techniques.”129 In this chapter, the term ASI intervention refers to the kind of individual occupational therapy that Ayres developed specifically to remediate sensory integrative problems in children.130 In this intervention, the therapist presents activity challenges that are individually tailored to improve the specific sensory integration problems affecting the child’s performance. This intervention is designed to help a child gain improved sensory integrative capabilities when problems with sensory integration are interfering with the child’s occupations at home, in play, at school, or in the community (Case Study 11-1). Although Ayres originally designed this therapy for children with learning disabilities,11 she and many other expert practitioners have used this kind of intervention, along with specific skill training and consultation, to help children with other disabilities, including autism.93,97

In designing this specialized form of occupational therapy, Ayres was influenced by the neurobiologic literature, which shows that the nervous system has plasticity or changeability. Plasticity is particularly characteristic of the developing young child. This led Ayres to hypothesize that the neural systems that impair function may be remediable, especially in the young child. Accordingly, she set out to design therapy that capitalized on the plasticity of the nervous system to remediate sensory integrative dysfunction. This is not to say that ASI intervention cures conditions such as learning disability, autism, or developmental delays. Rather, the intent is to improve the efficiency with which the nervous system interprets and uses sensory information for functional use. Therefore ASI is aimed at promoting underlying capabilities to the greatest degree possible.

ASI intervention has several defining characteristics. It is applied on an individual basis because the therapist must adjust therapeutic activities moment by moment in relation to the individual child’s interest in the activity or response to a specific challenge or sensory experience.49,81,85 This requires the therapist to continually focus attention on the child while being mindful of opportunities in the environment for eliciting adaptive responses. The therapist’s decisions regarding how and when to intervene involve a delicate interplay between the therapist’s judgment regarding the potential therapeutic value of an activity and the child’s motivation to do the activity. The therapist does not use a “cookbook” approach in providing this therapy (e.g., by entering the therapy situation with a predetermined schedule of activities that the child is required to follow). Rather, the therapist enters into a relationship with the child that fosters the child’s inner drive to actively explore the environment and to master challenges posed by the environment.

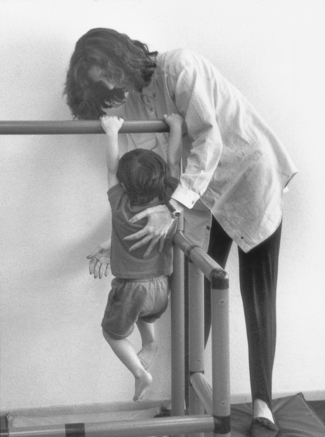

Intervention involves a balance between structure and freedom,11,18 and its effectiveness is contingent on the proficiency of the therapist in making judgments regarding when to step in to provide structure and when to step back and allow the child to choose activities. The therapist’s job is to create an environment that evokes increasingly complex adaptive responses from the child. To accomplish this, the therapist respects the child’s needs and interests while structuring opportunities to help the child successfully meet a challenge. An example is a child who needs to develop more efficient righting and equilibrium reactions and chooses to sit and swing on a platform swing. The therapist may allow the child to swing awhile to become accustomed to the vestibular sensations. Once the child seems comfortable, the therapist steps in to jiggle the swing to stimulate the desired responses. However, if the child responds to this challenge with signs of anxiety or fear, the therapist needs to intervene quickly to help the child feel safer. For example, the therapist might set an inner tube on the swing to provide a base to stabilize the lower part of the child’s body and increase feelings of security while the child’s upper body is free to make the required righting reactions. Therapeutic activities thus emerge from the interaction between therapist and child. Such individualized treatment can be fully realized only with one-to-one interaction between therapist and child (Figure 11-13).

FIGURE 11-13 Individual ASI intervention requires the therapist to attend closely to the child on a moment-by-moment basis to ensure that therapeutic activities are individually tailored to changing needs and interests of the child. Courtesy Shay McAtee.

The emphasis on the inner drive of the child is another key characteristic of ASI intervention.11,18,49,85 Self-direction on the part of the child is encouraged because therapeutic gains are maximized if the child is fully invested as an active participant. However, this is not to say that the child is permitted to engage in free play with no adult guidance. The optimal therapy situation is one in which a balance is struck between the structure provided by the therapist and some degree of freedom of choice on the part of the child.11,19 Drawing on the child’s interests and imagination is often key to encouraging greater effort on a difficult task or staying with a challenging activity for a longer time. However, because children with sensory integrative problems do not always demonstrate inner drive toward growth-inducing activities, it is often necessary to modify activities and to find ways to entice such children toward interaction. A relatively high degree of directedness often is needed when working with children with autism or other children whose inner drive is limited. Occasionally a therapist may use a high degree of directedness within the context of a particular activity to show a child that the challenging activity is possible not only to achieve, but also to enjoy.

Related to inner drive is another key feature of ASI intervention—the valuing of active participation, rather than passive participation, on the part of the child. Because the brain responds differently and learns more effectively when an individual is actively involved in a task rather than merely receiving passive stimulation, it is considered optimal for a child to be an active participant to the greatest degree possible. For example, sensory integration theory posits that a child experiences a greater degree of integration from pumping a swing or pulling on a rope to make it go than from being swung passively.

Maximal active involvement generally takes place when therapeutic activities are at just the right level of complexity, at which the child not only feels comfortable and nonthreatened but also experiences some challenge that requires effort. The course of therapy usually begins with activities in which the child feels comfortable and competent and then moves toward increasing challenges. For example, for children with gravitational insecurity, therapy usually begins with activities close to the ground and with close physical support from the therapist to help the child feel secure. Gradually, over weeks of therapy, activities that require stepping up on different surfaces and moving away from the floor are introduced as the therapist subtly withdraws physical support. Introducing just the right level of challenge, while respecting the child’s need to feel secure and in control, is a key to maximizing the child’s active involvement in therapy (Figure 11-14).

FIGURE 11-14 Rather than passively imposing vestibular input on the child, classic sensory integration treatment emphasizes active participation and self-direction of the child. Courtesy Shay McAtee.

However, there are situations in which passive stimulation is needed to help prepare a child for more complex or challenging activities. For example, the child with autism may show improved sensory registration after receiving passive linear vestibular stimulation.144 The improved registration means that the child has greater awareness of the environment, and thus the passive stimulation is a stepping stone toward active involvement in an activity. Another example is the use of passive tactile stimulation as a means for reducing tactile defensiveness.11,153 However, this aspect of therapy is seen as a limited component of a sensory integrative treatment program and then only as a step toward facilitating more active participation.

Another key characteristic of ASI intervention is the setting in which it takes place. The provision of a special therapeutic environment is an important aspect of this kind of intervention and has been described in detail by other authors.143,150 Based on the research that shows that brain structure and function are enhanced when animals are permitted to actively explore an interesting environment,79 a sensory-enriched environment is designed to evoke active exploration on the part of the child. The clinic that is designed for ASI intervention contains large activity areas with an array of specialized equipment. The availability of suspended equipment is a hallmark of this treatment approach.49,85 Suspended equipment provides rich opportunities for stimulating and challenging the vestibular system. In addition, equipment and materials are available that provide a variety of somatosensory stimuli, including tactile, vibratory, and proprioceptive. Mats and large pillows are used for safety. Overall, this special environment provides the child with a safe and interesting place in which to explore his or her capabilities. At the same time it provides the therapist with a tool kit for creating sensory experiences that are enticing and for gently guiding the child toward activities that challenge perception, dynamic postural control, and motor planning (Figure 11-15).

FIGURE 11-15 The setting in which classical sensory integration treatment takes place provides a variety of sensory experiences. Immersion in a pool of balls presents challenges to sensory modulation. Courtesy Shay McAtee.

Because of the prominence of vestibular based activities in the environments in which ASI is applied, a few cautionary words are in order regarding this powerful tool. Activation of the vestibular system, most often in the form of linear movement, is commonly introduced early in the course of treatment for many children because it is believed to have an organizing effect on other sensory systems.11,18,19 However, it can have a highly disturbing and disorganizing effect on the child if used carelessly. Vestibular system activation may produce strong autonomic responses, such as blanching and nausea. It directly influences the arousal level and, if not regulated carefully, may produce hyperactive, distractible states or lethargic, drowsy states. ASI intervention emphasizes active participation on the part of the child; therefore, vestibular stimulation is not passively imposed on the child. Rather, the child is allowed to initiate and actively participate in vestibular activities as much as possible, with the therapist stepping in to help modulate it when indicated. For example, if a child is actively rotating while sitting in a tire swing and begins to exhibit mild signs of autonomic activation, the therapist may intervene. The therapist may reduce the intensity of the swinging by guiding the child to shift to slow linear swinging or by offering the child a trapeze to pull to increase the amount of proprioceptive input. Proprioceptive input is believed to have an inhibiting effect on vestibular input, as indicated by results of animal research.69 Therefore, knowledge of the effects of vestibular stimulation and its interactions with other sensory systems is critical in this treatment approach. Responsible use of vestibular-based activities absolutely requires advanced training in sensory integration.

To summarize the key features of ASI intervention, therapeutic activities are neither predetermined nor are they simply free play. The flow of the treatment session results from a collaboration between the therapist and child in which the therapist encourages and supports the child in a way that moves the child toward therapeutic goals. This all takes place within a special environment that is safe yet challenging. The use of special equipment and powerful sensory modalities requires that the therapist have special training well beyond the entry level of practice in occupational therapy.

ASI intervention can be intensive and long term. Although treatment schedules vary, a typical schedule involves two sessions per week, each lasting 45 minutes to 1 hour. A typical course of therapy lasts for about 2 years. Most experts agree that at least 6 months of therapy is needed to detect results.

After Ayres developed ASI intervention,11,18 her colleagues and students continued to further develop and expand on her intervention concepts. Koomar and Bundy provided a particularly thorough description of the application of sensory integration procedures for specific types of sensory integrative disorders.85 Holloway has imported ASI concepts into the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), where the treatment principles are used to help young infants when their developing nervous systems are most plastic.76 Others have adapted ASI intervention to address the needs of infants and toddlers who are developmentally at risk,136 as well as the needs of children with visual impairments,126 cerebral palsy,33 environmental deprivation,47 and fragile X syndrome.75

Application of the ASI approach requires advanced study and training. Koomar and Bundy advocated a mentorship process as the best preparation for learning how to clinically apply sensory integration principles.85 Ayres also advocated this and established a 4-month course in which therapists receive both didactic instruction and intensive hands-on experience treating children under close supervision. Ayres believed that this level of intensity was required to master the sensory integration approach. Because of the highly specialized and complex nature of the classical sensory integration approach, it is important that occupational therapists gain mentored experience in this area before independently engaging in this form of practice.

In addition, ongoing study and discussion with peers are highly recommended to hone clinical expertise in this area after acquiring advanced training. Although ASI intervention as described here occurs within specialized therapy centers, many of the concepts can be applied in other settings as well. School-based occupational therapists have found ways to incorporate the central principles of ASI into the educational setting, including bringing specialized equipment into classrooms and playgrounds in ways that help to organize and prepare a child for learning. Successful therapy programs frequently involve helping families to understand and use the sensory integrative concepts that support and facilitate their children’s success by developing activities at home and identifying resources within the community that reinforce the experiences emphasized during therapy.120

Training in Specific Skill Development

Although ASI intervention is focused on improving foundational neural functions that allow a wide range of capabilities and skills to emerge, therapists will often want to help a child and family to develop specific skills or short-term coping strategies to deal immediately with the special challenges posed by sensory integration problems. For example, a child with poor proprioceptive feedback may need to keep up with handwriting exercises assigned in class. Application of individual ASI intervention would aim to help the child develop better body awareness that eventually will help not only with writing but also with catching, throwing, cutting, buttoning, and many other proprioception-dependent skills. However, because of everyday classroom stress from the demands of handwriting, the child may not be able to afford to wait for these generalized capabilities to develop through sensory integrative treatment. For this child, specific handwriting training may be used to help develop better handwriting skills, despite poor proprioceptive feedback. When working on specific skill development, the occupational therapist can still be mindful of the guiding principles of sensory integration theory (see Box 11-2). For example, it is optimal to involve self-direction and active participation as much as possible. This might be accomplished with the child in this example by having the child write stories related to individual interests and experiences. In addition, handwriting exercises that require active movement are expected to accomplish more than those dependent on passive guidance of the child’s hand. The therapist’s ability to read the child’s responses to writing activities helps ensure that the activities remain motivating and appropriately challenging.

Group Intervention

The occupational therapist working with a group of children cannot provide the same level of vigilance to individual responses that takes place during individual therapy. Therefore, some of the highly individualized applications of ASI intervention cannot be used within a group, nor can the therapist give the close guidance that is finely tuned to the individual child’s needs every moment of the treatment session. Again, however, the principles of ASI outlined in Box 11-3 are important concepts to incorporate into the group format as much as possible.

Working with children in a group provides the opportunity to observe some of the ways in which sensory integrative problems disrupt participation in a social context (Figure 11-16). Some problems emerge only in a group situation and may not be evident during individual therapy. For example, tactile defensiveness may not be apparent in the safe constraints of individual therapy but may become obvious as a child tries to participate within a group of people who are brushing by in an unpredictable manner. Observing how the group dynamic affects the child can help the therapist know what aspects of the classroom, playground, park, or after-school activities are likely to pose a threat or challenge (Case Study 11-2).

FIGURE 11-16 Group programs provide opportunities for children with sensory integrative disorders to develop coping skills that help them function in social context with peers. Courtesy Shay McAtee.

In some situations, external variables such as funding limitations, availability of staff, or organizational policies create the need for children to receive therapy in a group setting. It is important that occupational therapists make recommendations based primarily on the needs of the children being served, taking into consideration such outside factors, rather than allowing the external factors to dictate the type of intervention that is provided. It is also important to differentiate between what can be accomplished within a group versus an individual therapy session. Because group programs do not permit the same degree of intensive, individualized work, they are not expected to lead to the same outcomes.

An especially innovative application of sensory integration concepts to groups is reflected in the work of Williams and Shellenberger.154 Through a group format, their Alert Program helps children learn to recognize how they feel when their levels of alertness change throughout the day, to identify the sensorimotor experiences that they can use to change their level of alertness, and to monitor their arousal levels in a variety of settings. Another application of ASI concepts to groups is the work of Piantanida and Baltazar, who present a variety of sensory integration–based group activities for developing appropriate social skills.121

To apply sensory integration principles to a group program, an occupational therapist should be familiar enough with sensory integration theory to understand precautions and general effects of various sensory and motor activities. Experience and training in working with groups, including how to maintain the attention of children in a group, how to address varying skill and interest levels, and how to deal with behavioral issues, are also recommended for occupational therapists applying ASI principles in group programs.

Consultation on Modification of Activities, Routines, and Environments

Sensory integrative problems are complex and are often misinterpreted as behavioral, psychological, or emotional in origin. Helping family members, teachers, and others to understand the nature of the problem can be a powerful means toward helping the child. Providing information to those who are in ongoing contact with the child and developing strategies through collaboration with them are important ways in which the therapist can indirectly intervene to influence the child’s life positively across a variety of settings. Indirect intervention in the form of consultation is often critical for success in a comprehensive occupational therapy program for the child with sensory integration challenges.

Although many sensory integration concepts are not familiar to family members, teachers, or other professionals, once they are explained in everyday terms, a new understanding of the child often ensues. Cermak aptly referred to this process as demystification.47 Parents commonly express relief at finally having a name for behaviors that they have observed, and they may experience release from feeling that they have caused these problems through a maladaptive parenting style. Teachers also may appreciate having an alternative way to view child behaviors, especially when this new perspective is coupled with the application of strategies that promote responses from the child that are more productive.

Helping those around the child understand their own sensory integrative processes is sometimes a good way to make these new concepts more meaningful. Williams and Shellenberger use this tactic when introducing their Alert Program to promote optimal states of organization and levels of alertness.154 They encourage the adults being trained to administer the program to develop awareness and insight into their own sensorimotor preferences. This first step in initiating consultation is to help the significant adults in the child’s life better understand sensory integration in general and in relation to the specific child. This can be achieved through several avenues, including parent/teacher conferences, experiential sessions, lecture and discussion groups, professional in-services, and ongoing education programs. Whatever format is used, it is likely that the greater the understanding of the basic concepts of sensory integration, the greater the openness and willingness to address these problems (Figure 11-17).

FIGURE 11-17 Consultation in school involves joint problem solving between the occupational therapist and the teacher. Courtesy Shay McAtee.

Perhaps the most important component of any consultation program is providing guidance for identifying, preventing, and coping with the challenges in everyday life that stem from the sensory integrative problems. Sometimes specific activities can be suggested that will help a child to prepare for a challenging task. For example, a child who has tactile defensiveness may be better able to tolerate activities such as finger painting or sand play if some desensitization techniques, such as applying firm touch-pressure to the skin, are used just before the activity. Modifying the activity might involve providing tools to use with the paint or sand to give the child a ready “break” from the unpleasant sensation. A home program that includes gradual introduction of tactile sensation in a safe place, such as the bathtub, can also help to lessen reactions. The therapist can also promote success in activities by suggesting individualized ways to help a child through difficult tasks. For example, some children with dyspraxia are likely to be more successful in completing a novel task when they receive verbal directions, whereas others respond optimally to visual demonstrations, and still others need physical assistance with the motion. Determining which method or combination of methods is most likely to help the individual child can assist adults in facilitating success.

Making adjustments in the environment can be especially important in the school setting since children spend large amounts of time in this environment. For example, children with autism are often highly affected by the sensory characteristics of their environments. Finding ways to manage sound, lighting, contact with other people, environmental odors, and visual distractions in the classroom, playground, cafeteria, and assembly rooms can make an important difference in attention, behavior, and, ultimately, performance. Dunn’s work has led to a deeper understanding of how the sensory aspects of ordinary environments affect individuals who have the various sensory modulation styles that are depicted in her model (see Figure 11-9).61,63 Because individual differences in sensory processing tend to be lifelong tendencies, Dunn emphasizes how important it is for a person to learn to construct daily routines and manipulate sensory aspects of work and play environments in order to live as comfortably and successfully as possible.63 Consultation to develop the family’s insight into a child’s sensory characteristics, or to foster the child’s own insight, along with ideas for home and community-based activities, may be critical to intervention.

Procedures or techniques that require advanced training of an occupational therapist should not be recommended for parents and other professionals. For example, an appropriate consultation program never attempts to train a parent or teacher to provide individual therapeutic activities that require advanced training for monitoring the child’s response. Therapists should also be familiar enough with the child to be aware of any precautions that might apply before they make any suggestions. For example, some children display delayed responses to vestibular stimulation and can become overstimulated or lethargic hours after engaging in activities involving this type of sensation. Some sensory integrative techniques can lead to adverse reactions and must be used with care. Consultation services, environmental modifications, and home programs are meant to supplement, not replace, direct intervention. Used appropriately, they provide effective avenues for supporting the child, as well as family members, teachers, and other professionals who share in the efforts to help the child succeed.

The same therapist qualifications needed to provide individual ASI intervention are desirable in using consultation because the therapist needs to be able to predict what the child’s likely responses will be to various activities and situations, given the characteristics of the child’s sensory integrative difficulties. In addition, the therapist should be well enough versed in sensory integration concepts to be able to explain them in simple yet meaningful terms. Also, it is imperative that the therapist have excellent communication skills and respect for the various people and environments that are involved. Bundy provided an excellent description of the communication process involved in a good consultation program.38

Expected Outcomes of Occupational Therapy

As discussed previously, occupational therapy is not expected to “cure” sensory integrative problems. Rather, occupational therapy aims to improve the child’s health and quality of life through engagement in meaningful and important occupations or activities. To accomplish this with a child who has sensory integrative problems, the occupational therapist may aim to improve sensory integrative functions through direct remediation via ASI intervention, to minimize the effects of the problems by teaching the child specific skills and strategies, and by consulting with parents and teachers to plan modifications of activities, routines, and environments. Often remediation, skill training, and consultation are thoughtfully combined in an intervention plan that is tailored to the particular needs of the child and family.

The goals and objectives that are formulated as part of a child’s intervention plan target specific occupations in which positive changes are expected. These goals and objectives can be conceptualized as falling under the traditional occupational categories of work, rest, play, and self-care. For example, a toddler who tends to be overstimulated much of the time because of severe sensory modulation problems may consequently have difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. One result of this situation is sleep deprivation, which aggravates defensiveness and behavior problems. A goal addressing the occupational domain of rest may be for the child to acquire more predictable sleep patterns with adequate amounts of sleep. A corresponding behavioral objective might be that the child will take a midday nap of at least 1 hour for 3 days per week. The intervention could involve direct remediation to reduce the sensory defensiveness as well as parent consultation on strategies such as calming activities, a very predictable activity schedule including a specific rest time ritual, and creation of an arousal-reducing environment after lunch (e.g., lights dimmed and noise reduced and screened with rhythmic sounds or “white noise”).

Sometimes specific behavioral objectives that address performance skills are appropriate as a way to monitor progress toward the desired changes in daily occupations. Goals can be conceptualized as falling into seven general categories of expected outcomes that address performance skills and patterns, as well as occupational engagement. These outcomes are summarized in Box 11-3; more detailed descriptions of each category follow.

Increase in the Frequency or Duration of Adaptive Responses

As discussed in the introduction of this chapter, adaptive responses occur when an individual responds to environmental challenges with success. Application of ASI principles helps the therapist envision how to create opportunities for the child to make adaptive responses. This may be accomplished through systematic use of sensory input to promote organization within the child’s nervous system. Ensuring that the sensory inputs inherent in activities are organizing rather than disorganizing and integrating rather than overwhelming requires careful monitoring on the part of the therapist, who must be sensitive to the child’s response to each aspect of an activity and to each type of sensory input involved. The ASI intervention approach intensively focuses on the child’s demonstration of higher level adaptive responses. However, specific skill training, group intervention, and consultation services may also boost the frequency and duration of adaptive responses by changing the child’s everyday environments in ways that enable the child to make adaptive responses more easily.

Increasing the duration and frequency of adaptive responses is an important outcome of sensory integration because functional behavior and skills are developed by mastering simple adaptive responses. For example, a child who has difficulty staying with an activity for more than a few seconds tends to shift from one activity to another. A desirable outcome for that child might be to stay for a longer time with a simple activity, such as swinging, in a therapy environment. Achievement of this simple adaptive response may eventually contribute to the functional behavior of staying with the reading circle in the school classroom for the required amount of time, despite the many distractions and cognitive challenges imposed by this occupation.

Development of Increasingly More Complex Adaptive Responses

Adaptive responses can vary in complexity, quality, and effectiveness.19 A simple adaptive response might be simply holding onto a moving swing. A more complex adaptive response involving timing of action might be releasing grasp on a trapeze at just the right moment to land on a pillow. Over time, effective ASI intervention is expected to enable the child to make adaptive responses that are more complex. This outcome is based on the assumption that sensory integrative procedures promote more efficient organization of multisensory input at primitive levels of functioning, which in turn is expected to enhance functions that are more complex. The result is an improvement in the child’s ability to make judgments about the environment, what can be done with objects, and what specific actions need to be taken to accomplish a goal.19

Although repetition of a familiar activity may be important while a child is assimilating a new skill and may be useful in helping a child get ready for another, more challenging activity, development of increasingly more complex abilities occurs only when tasks become slightly more challenging than the child’s previous accomplishments. Presenting activities slightly above the child’s current skills levels is one of the main tenets of ASI intervention. Because of the high degree of personal attention continuously given to the child during this kind of therapy, a fine gradient of complexity can be built into therapeutic activities while simultaneously ensuring that the child experiences success and a growing sense of “I can do it!”

Group programs, compared with individual therapy, tend to place greater demands on children for several reasons, including limited opportunity for individualization of activities, the presence of other children with their unpredictable behaviors, and reduced opportunity for direct assistance from the therapist. Thus, a limitation posed by group programs is that challenges imposed on the group may at times be too great for an individual child, leading to frustration and failure. The therapist who provides a group program needs to be alert to the potential for this undesirable effect and strive to avoid it as much as possible. Whatever format for intervention is used, the therapist uses activity analysis, assessment information, ongoing observations, and knowledge of child development to ensure that the program engages the child’s inner drive as much as possible to draw forth increasingly more complex interactions within the clinical, school, home, or community environments.

Improvement in Gross and Fine Motor Skills

The child who makes consistent and more complex adaptive responses shows evidence of improved sensory integration. Moreover, this child meets new challenges with greater self-confidence. A net result of these gains frequently is greater mastery in the motor domain. An example is the child with a vestibular processing problem who exhibits greater competency and interest in playground activities and sports after individual ASI intervention, even though these activities were not practiced during therapy. Motor skills may be among the earliest complex skills to show measurable change in response to an ASI approach, probably because of the extent of the motor activity inherent in this intervention approach. Skill training, group intervention, or consultation for children with sensory integrative problems should result in improvement of specific motor skills if these are targeted by the intervention. For example, if a skill-training approach to handwriting is used to help a child with poor somatosensory perception, specific gains in handwriting performance should follow if the intervention is successful.

Improvement in Cognitive, Language, or Academic Performance

Although cognitive, language, and academic skills are not usually the specific objectives of sensory integration–based occupational therapy, improvement in these domains has been detected in some effectiveness studies involving the provision of ASI intervention.10,15,17,23,42,92,123,151 Application of ASI therapeutic procedures is thought to generate broad-based changes in these areas secondary to enhancement of sensory modulation, perception, postural control, or praxis.18,19,43 For example, a child with autism may be helped through a sensory integrative approach to respond in a more adaptive way to sights, sounds, touch, and movement experiences that initially were disturbing. This improvement in sensory modulation may lead to a better ability to attend to language and academic tasks; thus, improvement in these areas may follow. A child who has a vestibular processing disorder may improve in postural control and equilibrium, freeing the child to more efficiently concentrate on academic material without the distraction of frequent loss of sitting balance or loss of place while copying from the blackboard. This child’s vestibular-related improvements are also likely to have a positive effect on playground and sports activities because effects of classic sensory integration treatment are expected to generalize to a wide range of outcome areas.

Occupational therapy aimed at developing specific skills such as improved handwriting also may free the child to focus on the conceptual aspects of academic tasks rather than the perceptual-motor details of how to write letters on a page or how to keep a sentence on a printed line. For such interventions, effects on outcome skills tend to be limited to the specific task of concern. Similarly, consultation programs may enhance language, cognitive, or academic skills by providing strategies for reducing the effect of sensory integrative disorders on these functions. For instance, helping a teacher understand how best to seat a child in class (such as in a beanbag chair versus a firm wooden chair or in the front corner of the room near the teacher’s desk) may help reduce the negative effects of a sensory integrative problem by making it easier for the child to attend to instruction in the classroom.

Increase in Self-Confidence and Self-Esteem

Ayres asserted that enhanced ability to make adaptive responses promotes self-actualization by allowing the child to experience the joy of accomplishing a task that previously could not be done.18 The outcome of therapy that encourages successful, self-directed experiences is a child who perceives the self as a competent actor in the world. Individual and group programs and direct and indirect services all can be geared to helping the child master the activities that are personally meaningful and essential to success in the world of everyday occupations. Mastery of such activities is expected to result in feelings of personal control that, in turn, lead to increased willingness to take risks and to try new things.18 For example, a child with gravitational insecurity may experience not only fear responses to climbing and movement activities, but also feelings of failure and frustration at not being able to participate in the play of peers. In such a case, an increase in self-confidence and comfort in one’s physical body is often accompanied by a general boost in feelings of self-efficacy and worth. Cohn, Miller, and Tickle-Degnen noted that parents’ perceptions of the benefits of occupational therapy using a sensory integrative approach included a reconstruction of self-worth, in addition to improvement in abilities and activities.53 Parents in this study perceived that this intervention enabled their children to take more risks and to try new things, thus opening the door to greater possibilities.

Enhanced Occupational Engagement and Social Participation

Occupational therapy programs that address sensory integrative problems encourage the child to organize his or her own activity, particularly in the ASI intervention approach. As the child develops general sensory integrative capabilities and improved strategies for planning action, gains are seen in relation to the ability to master self-care tasks, to cope with daily routines, and to organize behavior more generally.18 As a result, the child often is able to participate more fully in the occupations that are typical for his or her peers, a broad but critically important outcome for social participation. For example, intervention may help the child who is overly sensitive to touch or movement to deal with sensations in a more adaptive manner. As a result, the child approaches and engages in the challenges of everyday occupations, such as getting himself or herself ready for school in the morning, sharing a table with others in the school cafeteria, behaving appropriately in the classroom, and playing with friends on the playground with greater security and confidence. As noted previously, Cohn et al. reported that parents viewed their children as more willing to try new experiences following intervention, thus enhancing their opportunities for social participation.53 Not only is participation in daily occupations performed with greater competency and satisfaction, but relationships with others are likely to become more comfortable and less threatening. Group therapy programs are ideal arenas in which the increases in self-confidence made in individual therapy can be tried out in the more challenging context of a social setting. Gains in occupational engagement and social participation are among the most significant of intervention outcomes.

Enhanced Family Life

When children with sensory integrative problems experience positive changes during intervention, their lives and the lives of other family members may be enhanced. One possible by-product of intervention based on ASI principles is that parents gain a better understanding of their children’s behavior and begin to generate their own strategies for organizing family routines in a way that supports the entire family system. This kind of change can be particularly powerful for parents of children with autism, whose perceptions of child behaviors may be reframed as they become familiar with the sensory integrative perspective. For example, behavior that is interpreted as bizarre, such as insisting on wearing rubber bands on the arms, may be reframed as a meaningful strategy that the child uses to obtain deep pressure input for self-calming.2 Instead of viewing the behavior as a frustrating, pathologic sign that should be eliminated, reframing may lead the parents to explore other ways that they could provide the child with the deep pressure experiences that he or she seeks. Thus, an important outcome of sensory integrative intervention may include changes in parents’ understanding of the child, leading to new coping strategies and alleviation of parental stress.52 In her studies of parental perspectives, Cohn has found that an important outcome of the sensory integrative approach is that parents tend to “reframe” their view and expectations of their children in a positive manner.50,51

Measuring Outcomes

Because every child with a sensory integrative problem is unique, the expected outcomes of occupational therapy using an ASI approach are individualized and diverse. Outcomes are sometimes measured using standardized tests. In fact, some of the SIPT tests (e.g., Design Copying, Standing and Walking Balance, and most of the praxis tests) are good measures of change because of their strong test–retest reliability, in addition to being relevant to concerns that are commonly voiced by parents and teachers. However, standardized tests often do not address key occupational issues.

Goal attainment scaling (GAS) is an alternative to standardized tests that addresses the uniquely individualized nature of expected outcomes of ASI. The GAS method was developed in the mental health arena as a program evaluation tool to facilitate patient participation in the goal-setting process.83 GAS provides a means to prioritize goals that are specifically relevant to individuals and their families and to quantify the results using a standard metric that allows comparison of achievement across different types of goals. This process also captures functional and meaningful aspects of an individual’s progress that are often challenging to assess using available standardized measures. For this reason, GAS is an attractive methodology for measuring change during occupational therapy, and it has now been successfully applied in occupational therapy effectiveness research in a variety of settings, including rehabilitation,80,110 school systems,58,82 and mental health programs.90,140 This approach seems promising for capturing the diverse changes that are reported following ASI intervention programs.95 Case examples demonstrating how GAS has been applied to measure outcomes of ASI-based occupational therapy are described by Miller and Summers.108 In a randomized, controlled clinical trial, GAS detected significant improvements among children who received ASI intervention, compared to children receiving alternative conditions.106

Research on Effectiveness of Intervention

Therapists who wish to use an ASI approach in practice need to keep up to date on research in this field to ensure that intervention is informed by the growing knowledge base. Research on the effectiveness of ASI-based interventions is particularly critical to evidence-based practice in this specialty area.

In a meta-analysis of experimental research on sensory integrative treatment, Vargas and Camilli analyzed 16 studies comparing sensory integrative treatment with no treatment and 16 studies comparing sensory integrative treatment with alternative treatments.149 These included studies of adults as well as studies in which the descriptions of intervention were inconsistent with ASI principles. A significant overall average effect size of 0.29 was found for sensory integrative treatment compared with no treatment, indicating an advantage for children receiving the treatment. The largest effect sizes were found for psychoeducational and motor outcome measures. However, older studies had a significantly higher effect size than more recent studies, which did not have a significant effect size when considered by themselves. The average effect size for sensory integrative treatment compared with alternative treatments was 0.09, a quite small effect, and the sensory integrative treatments did not differ significantly from alternative treatments in effect size.

The decline in effect size of sensory integrative treatment studies over the years is puzzling. The authors of the meta-analysis suggest that the reason for this finding may lie in some unidentified difference in treatment implementation, or with selection and assignment of participants to experimental and control groups in the older studies versus the more recent ones.149 They point out that, in general, the studies examined sensory integration intervention in isolation and therefore do not represent the ways that sensory integration is implemented clinically, which usually involve incorporation of other treatment methods in addition to those that adhere to ASI principles. Another plausible explanation not explored by these authors is that, although the studies included in this meta-analysis all claimed to study intervention based on the work of Ayres, the interventions delivered in the studies were not all consistent with the core elements and key therapeutic strategies of ASI. This limitation is called a problem with fidelity, discussed further on.

After examining the effectiveness research on sensory integration, both Miller103 and Mulligan112 concluded that the effectiveness of sensory integration–based occupational therapy is neither proved nor unproved. This is because all of the existing studies that support the effectiveness of sensory integration intervention, as well as those that do not support its effectiveness, are flawed. Randomized, controlled clinical trials are considered to yield valid results only if they adhere to four standards: replicable intervention, homogeneous sample, sensitive and relevant outcome measures, and rigorous methodology.34

Many studies used unclear or unsound methods to identify who is to receive sensory integration treatment. This created the possibility that some children who do not have sensory integrative dysfunction were inappropriately assigned to this treatment. An exemplary pilot study with respect to selection of participants is the small randomized, controlled clinical trial conducted by Miller, Coll, and Schoen, who focused on effectiveness of ASI intervention for children with sensory modulation disorders (Research Note 11-2).106 These researchers carefully selected children using behavioral and physiologic measures to confirm the presence of sensory modulation disorder and then randomly assigned each child to one of three conditions: individual ASI intervention, an alternative tabletop activity program, or a passive placebo condition. Results showed that children who had received ASI intervention had better outcomes than children in the other conditions, and that some of their gains were statistically significant, specifically in Goal Attainment Scaling measures, as well as measures of attention and cognitive/social functioning.

Another common flaw is lack of fidelity. Fidelity refers to the extent to which the intervention provided in a study is faithful to the key elements of the intervention approach. Sometimes investigators use a rigid or very limited treatment protocol in an effort to ensure that the sensory integration treatment is well defined and adheres to strict criteria. Although the purpose of this strategy is laudable (i.e., to ensure that the treatment is replicable), it may result in an intervention that lacks fidelity to the core elements of the sensory integration approach. This is because a rigid treatment protocol is incompatible with the highly individualized, child-centered, fluid nature of ASI intervention; therefore, any results obtained do not represent the effects of ASI intervention. On the other hand, if treatment guidelines are too vague, or are not checked systematically during the delivery of the intervention, one cannot trust that the intervention was delivered in a consistent manner across the participants and across the intervention period of the study.

To examine fidelity in sensory integration research, Parham et al. conducted a systematic review of 61 separate published studies that purportedly evaluated the effectiveness of sensory integration–based occupational therapy.116 Of the 61 studies, 34 provided this intervention to participants in the age range for which it was developed, preschool through elementary school age, without combining it with a non–sensory integration intervention. These 34 studies were analyzed for whether their descriptions of intervention adhered to key elements of ASI intervention that the authors and collaborating clinicians had extracted from the sensory integration literature. Results showed that only one of the key elements, “presents sensory opportunities,” was described in the majority of studies. More than one third of the studies contained sensory integration intervention descriptions that were contrary to one of the key elements, “collaborates with child on activity choice.” This is because, in these studies, the specific activities to be used in the intervention were determined by the researcher or the treating therapist prior to provision of intervention, rather than emerging from the interactions between child and therapist. Moreover, only one study used a quantifiable instrument to measure fidelity of intervention, and this instrument documented use of activities and equipment rather than the process of intervention. Parham et al. concluded that the effectiveness of sensory integration intervention cannot yet be made with confidence due to the lack of intervention fidelity in this research.116 To address this fidelity problem, a national network of occupational therapy researchers and practitioners, the Sensory Integration Research Collaborative (SIRC), developed a reliable and valid instrument, the Sensory Integration Fidelity Measure, to be used in research on ASI intervention.118 This instrument contains ratings of the structural background aspects of intervention, such as therapist qualifications and equipment, as well as ratings of the process of therapy (i.e., the therapeutic strategies used by the intervener during a therapy session), that reflect the core elements of ASI intervention.

Another common problem in sensory integration outcomes research is related to selection of outcome measures. Often children’s responses to ASI intervention are as individualized as the intervention strategies, making it difficult, perhaps impossible, for the researcher to select tests and other measurements that target the precise areas of gain for individual children. Moreover, it is likely that children with different types of sensory integrative problems respond to this treatment with different kinds of gains. For example, children with tactile defensiveness are likely to show gains in outcome domains different from those in which children with vestibular processing difficulties made progress; yet almost all of the research studies lump children together with sensory integrative problems as if they should have similar responses to a standard treatment. This certainly was not Ayres’s view, because she spent considerable effort attempting to identify subgroups of children with sensory integrative problems who might differ from one another with respect to degree and type of responsiveness to intervention.10,17,26 It is hoped that researchers who conduct future effectiveness studies will become more sensitive to this important issue.

Another important issue that is rarely addressed is the maintenance of long-term gains after completion of a period of ASI-based occupational therapy is completed. An encouraging finding reported by Wilson and Kaplan suggests that children who receive sensory integration intervention may obtain long-term benefits that are not obtained by children who receive other interventions.155 These researchers retested children who had participated in an earlier randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing sensory integration intervention with tutoring. Although no significant differences in outcomes were found between the two intervention groups in the original study,156 at follow-up 2 years later, only the children who had received the sensory integration treatment maintained the gross motor gains that they had made after intervention. Maintenance of intervention gains is a critical issue that has an influence on cost-effectiveness questions. Replication of Wilson and Kaplan’s findings155 using the Sensory Integration Fidelity Measure to document the intervention would make an important contribution to understanding the extent to which gains after sensory integration treatment can be maintained.

Although group experimental treatment designs are considered to be the gold standard of effectiveness studies, other research designs examining treatment outcomes also make valuable contributions to an understanding of the potential effects of sensory integration intervention. Single system research has been particularly useful in revealing individual differences in responses to sensory integrative treatment. In this kind of research, a child serves as his or her own control and is monitored repeatedly before intervention (the baseline phase) and during intervention. An advantage to this approach is that behavioral outcomes can be highly individualized and tracked over time to provide a snapshot of each child’s response to intervention. An example of this type of research is the study conducted by Linderman and Stewart on two preschoolers with pervasive developmental disorders. The researchers measured three behavioral outcomes for each child.89 Each outcome was observed in the child’s home and was tailored to address functional issues for each child (e.g., response to holding and hugging for one child and functional communication during mealtime for the other). Results indicate significant improvements between baseline and intervention phases for five of the six outcomes measured.

A great deal of investigation remains to be done to explore questions regarding effectiveness of interventions based in ASI. It would be particularly beneficial to be able to better predict who will best respond to individual ASI intervention and who may be better served by other interventions. The effectiveness of combining individual ASI intervention with other ASI-informed interventions, such as specific skill training, group programs, or consultation, is another area in need of research, particularly because such intervention combinations are typically done in clinical practice. The kinds of outcomes likely to proceed from various treatment approaches and the timeframes in which those outcomes can be expected to emerge deserve close examination in effectiveness studies. Long-term maintenance of gains, particularly of those related to outcomes that are measures of social participation, is a particularly important question that should be addressed in research. Finally, studies need to explore which intervention outcomes are most meaningful to the families of children with sensory integration problems to ensure that intervention programs are responsive to the needs of the people served.

REFERENCES

1. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. (2nd ed). American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;62:625–668.

2. Anderson, E.L. Parental perceptions of the influence of occupational therapy utilizing sensory integrative techniques on the daily living skills of children with autism. Los Angeles: University of Southern California, 1993. [Unpublished master’s thesis].

3. Ayres, A.J. The Eleanor Clark Slagle Lecture. The development of perceptual-motor abilities: A theoretical basis for treatment of dysfunction. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1963;17:221–225.

4. Ayres, A.J. Tactile functions: Their relation to hyperactive and perceptual motor behavior. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1964;18:6–11.

5. Ayres, A.J. Patterns of perceptual-motor dysfunction in children: A factor analytic study. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1965;20:335–368.

6. Ayres, A.J. Interrelations among perceptual-motor abilities in a group of normal children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1966;20:288–292.

7. Ayres, A.J. Interrelationships among perceptual-motor functions in children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1966;20:68–71.

8. Ayres, A.J. Deficits in sensory integration in educationally handicapped children. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1969;2(3):44–52.

9. Ayres, A.J. Characteristics of types of sensory integrative dysfunction. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1971;25:329–334.

10. Ayres, A.J. Improving academic scores through sensory integration. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1972;5:338–343.

11. Ayres, A.J. Sensory integration and learning disorders. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1972.

12. Ayres, A.J. Southern California Sensory Integration Tests. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1972.

13. Ayres, A.J. Types of sensory integrative dysfunction among disabled learners. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1972;26(1):13–18.

14. Ayres, A.J. Southern California Postrotary Nystagmus Test. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1975.

15. Ayres, A.J. The effect of sensory integrative therapy on learning disabled children: The final report of a research project. Los Angeles: Center for the Study of Sensory Integrative Dysfunction, 1976.

16. Ayres, A.J. Cluster analyses of measures of sensory integration. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1977;31(6):362–366.

17. Ayres, A.J. Learning disabilities and the vestibular system. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1978;11(1):30–41.

18. Ayres, A.J. Sensory integration and the child. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1979.

19. Ayres, A.J. Aspects of the somatomotor adaptive response and praxis. [Audiotape]. Pasadena, CA: Center for the Study of Sensory Integrative Dysfunction, 1981.

20. Ayres, A.J. Developmental dyspraxia and adult-onset apraxia. Torrance, CA: Sensory Integration International, 1985.

21. Ayres, A.J. Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1989.

22. Ayres, A.J. Sensory integration and the child, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 2004.

23. Ayres, A.J., Mailloux, Z. Influence of sensory integration procedures on language development. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1981;35(6):383–390.

24. Ayres, A.J., Mailloux, Z., Wendler, C.L.W. Developmental apraxia: Is it a unitary function. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 1987;7:93–110.

25. Ayres, A.J., Marr, D. Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests. In: Fisher A.G., Murray E.A., Bundy A.C., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 1991:203–250.

26. Ayres, A.J., Tickle, L. Hyperresponsivity to touch and vestibular stimuli as a predictor of positive response to sensory integration procedures in autistic children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1980;34:375–381.

27. Bach-Y-Rita, P. Brain plasticity. In: Goodgold J., ed. Brain plasticity. St. Louis: Mosby, 1981.

28. Baranek, G.T., Foster, L.G., Berkson, G. Sensory defensiveness in persons with developmental disabilities. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 1997;17:173–185.

29. Beckett, C., Maughan, B., Rutter, M., Castle, J., Colvert, E., Groothues, C., et al. Do the effects of early severe deprivation on cognition persist into early adolescence Findings from the English and Romanian Adoptees Study. Child Development. 2006;77:696–711.

30. Beery, K.E., Beery, N.A. The Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration, 5th ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 2006.

31. Bennett, E.L., Diamond, M.C., Krech, D., Rosenzwieg, M.R. Chemical and anatomical plasticity of brain. Science. 1964;146:610–619.

32. Blanche, E.I. Observations based on sensory integration theory. Torrance, CA: Pediatric Therapy Network, 2002.

33. Blanche, E., Schaaf, R. Proprioception: A cornerstone of sensory integrative intervention. In: Roley S.S., Blanche E.I., Schaaf R.C., eds. Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations. San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders; 2001:385–408.

34. Boruch, R.F. Randomized experiments for planning and evaluation: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997.

35. Bretherton, I., Bates, E., McNew, S., Shore, C., Williamson, C., Beeghly-Smith, M. Comprehension and production of symbols in infancy: An experimental study. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17:728–736.

36. Brown, C., Dunn, W. Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, 2002.

37. Bruininks, R.H., Bruininks, B. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency examiner’s manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, 2006.

38. Bundy, A.C. Using sensory integration theory in schools: Sensory integration and consultation. In: Bundy A.C., Lane S.J., Murray E.A., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2002:309–332.

39. Bundy, A.C., Murray, E.A. Sensory integration: A. Jean Ayres’ theory revisited. In: Bundy A.C., Lane S.J., Murray E.A., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2002:141–165.

40. Burke, J.P., Schaaf, R.C., Hall, T.B.L. Family narratives and play assessment. In: Parham L.D., Fazio L.S., eds. Play in occupational therapy for children. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008:195–215.

41. Burleigh, J.M., McIntosh, K.W., Thompson, M.W. Central auditory processing disorders. In: Bundy A.C., Lane S.J., Murray E.A., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2002:141–165.

42. Cabay, M. The effect of sensory integration–based treatment on academic readiness of young, “at risk” school children. Phoenix, AZ: Annual conference of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 1988.

43. Cabay, M., King, L.J. Sensory integration and perception: The foundation for concept formation. Occupational Therapy in Practice. 1989;1:18–27.

44. Case-Smith, J. The effects of tactile defensiveness and tactile discrimination on in-hand manipulation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;45:811–818.

45. Cermak, S.A. The relationship between attention deficits and sensory integration disorders (Part I). Sensory Integration Special Interest Section Newsletter. 1988;11(2):1–4.

46. Cermak, S.A. Somatodyspraxia. In: Fisher A.G., Murray E.A., Bundy A.C., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 1991:137–170.

47. Cermak, S.A. The effects of deprivation on processing, play and praxis. In: Roley S.S., Blanche E.I., Schaaf R.C., eds. Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations. San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders; 2001:385–408.

48. Chugani, H.T., Phelps, M.E. Maturational changes in cerebral function in infants determined by 18FDG positron emission tomography. Science. 1986;231:840–843.

49. Clark, F.A., Mailloux, Z., Parham, D. Sensory integration and children with learning disorders. In: Pratt P.N., Allen A.S., eds. Occupational therapy for children. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1989:457–509.

50. Cohn, E.S. From waiting to relating: Parents’ experiences in the waiting room of an occupational therapy clinic. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;55:168–175.

51. Cohn, E.S. Parent perspectives of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;55:285–294.

52. Cohn, E.S., Cermak, S.A. Including the family perspective in sensory integration outcomes research. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;52:540–546.

53. Cohn, E.S., Miller, L.J., Tickle-Degnen, L. Parental hopes for therapy outcomes: Children with sensory modulation disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000;54:36–43.

54. Coster, W., Deeney, T., Haltwanger, J., Haley, S. School Function Assessment. San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders, 1998.

55. Cui, M., Yang, Y., Zhang, J., Han, H., Ma, W., Li, H., et al. Enriched environment experience overcomes the memory deficits and depressive-like behavior induced by early life stress. Neuroscience Letters. 2007;404:208–212.

56. Daunhauer, L., Cermak, S. Play occupations and the experience of deprivation. In Parham D., Fazio L., eds.: Play in occupational therapy for children, 2nd ed., St. Louis: Mosby, 2008.

57. Davies, P.L., Gavin, W.J. Validating the diagnosis of sensory processing disorders using EEG technology. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61:176–189.

58. Dreiling, D.S., Bundy, A.C. A comparison of consultative model and direct-indirect intervention with preschoolers. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2003;57:566–569.

59. Dru, D., Walker, J.P., Walker, J.B. Self-produced locomotion restores visual capacity after striate lesion. Science. 1975;187:265–266.

60. Dunn, R., Dunn, K., Perrin, K.J. Teaching young children through their individual learning styles. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1994.

61. Dunn, W.W. The impact of sensory processing abilities on the daily lives of young children and families: A conceptual model. Infants and Young Children. 1997;9(4):23–25.

62. Dunn, W.W. Sensory Profile: User’s manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1999.

63. Dunn, W.W. The sensations of everyday life: Empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;55:608–620.

64. Dunn, W.W. The Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 2002.

65. Dunn, W. Sensory Profile School Companion manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 2006.

66. Dunn, W., Fisher, A.G., Sensory registration, autism, and tactile defensiveness. Melvin, J., eds. Occupational therapy in practice, Rockville, MD, American Occupational Therapy Association, 1983;Vol. 1:181–182.

67. Dunn, W., Myles, B.S., Orr, S. Sensory processing issues associated with Asperger syndrome: A preliminary investigation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:97–102.

68. Fisher, A.G. Vestibular-proprioceptive processing and bilateral integration and sequencing deficits. In: Fisher A.G., Murray E.A., Bundy A.C., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 1991:69–107.

69. Fredrickson, J.M., Schwartz, D.W., Kornhuber, H.H. Convergence and interaction of vestibular and deep somatic afferents upon neurons in the vestibular nuclei of the cat. Acta Otolaryngologica. 1966;61:168–188.

70. Gregg, C.L., Hafner, M.E., Korner, A. The relative efficacy of vestibular-proprioceptive stimulation and the upright position in enhancing visual pursuit in neonates. Child Development. 1976;47:309–314.

71. Gregory-Flock, J.L., Yerxa, E.J. Standardization of the prone extension postural test on children ages 4 through 8. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1984;38:187–194.

72. Gunnar, M.R., Barr, R.G. Stress, early brain development, and behavior. Infants and Young Children. 1998;11(1):1–14.

73. Henderson, A., Pehoski, C., Murray, E. Visual-spatial abilities. In: Bundy A.C., Lane S.J., Murray E.A., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2002:123–140.

74. Hensch, T.K. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2005;6:877–888.

75. Hickman, L. Sensory integration and fragile X syndrome. In: Roley S.S., Blanche E.I., Schaaf R.C., eds. Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations. San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders; 2001:385–408.

76. Holloway, E. Early emotional development and sensory processing. In: Case-Smith J., ed. Pediatric occupational therapy and early intervention. Boston: Andover Medical; 1998:163–197.

77. Hubel, D.H., Wiesel, T.N. Receptive fields of cells in striate cortex of very young, visually inexperienced kittens. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1963;26:994–1002.

78. Salihagic-Kadic, A., Kurjak, A., Medic, M., Andonotopo, W., Azumendi, G. New data about embryonic and fetal neurodevelopment and behavior obtained by 3D and 4D sonography. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2005;33:478–490.

79. Jacobs, S.E., Schenider, M.L. Neuroplasticity and the environment. In: Roley S.S., Blanche E.I., Schaaf R.C., eds. Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations. San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders; 2001:29–42.

80. Joyce, B.M., Rockwood, K.J., Mate-Kole, C.C. Use of goal attainment scaling in brain injury in a rehabilitation hospital. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1994;73(1):10–14.

81. Kimball, J.G. Sensory integrative frame of reference. In: Kramer P., Hinojosa J., eds. Frames of reference for pediatric occupational therapy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999. [(pp. 169–204)].

82. King, G.A., McDougall, J., Tucker, M.A., Gritzan, J., Malloy-Miller, T., Alambets, P., et al. An evaluation of functional, school-based therapy services for children with special needs. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 1999;19(2):5–29.

83. Kiresuk, T.J., Smith, A., Cardillo, J.E. Goal attainment scaling: Applications, theory, and measurement. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994.

84. Knickerbocker, B.M. A holistic approach to learning disabilities. Thorofare, NJ: C.B. Slack, 1980.

85. Koomar, J.A., Bundy, A.C. Creating direct intervention from theory. In: Bundy A.C., Lane S.J., Murray E.A., eds. Sensory integration: Theory and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2002:261–308.

86. Lai, J.S., Parham, L.D., Johnson-Ecker, C. Sensory dormancy and sensory defensiveness: Two sides of the same coin. Sensory Integration Special Interest Section Quarterly. 1999;22:1–4.

87. Lee, J.R.V. Parent ratings of children with autism on the Evaluation of Sensory Processing (ESP). Los Angeles: University of Southern California, 1999. [Unpublished master’s thesis].

88. Lee, H.W., Shin, J.S., Webber, W.R.S., Crone, N.E., Gingis, L., Lesser, R.P. Reorganisation of cortical motor and language distribution in human brain. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2009;80:285–290.

89. Linderman, T.M., Stewart, K.B. Sensory integrative-based occupational therapy and functional outcomes in young children with pervasive developmental disorders: A single-subject study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1999;53:207–213.

90. Lloyd, C. The process of goal setting using goal attainment scaling in a therapeutic community. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 1986;6(3):19–30.

91. Magalhaes, L.C., Koomar, J., Cermak, S.A. Bilateral motor coordination in 5- to 9-year-old children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1989;43:437–443.

92. Magrun, W.M., Ottenbacher, K., McCue, S., Keefe, R. Effects of vestibular stimulation on spontaneous use of verbal language in developmentally delayed children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1981;35:101–104.

93. Mailloux, Z. Sensory integrative principles in intervention with children with autistic disorder. In: Roley S.S., Blanche E.I., Schaaf R.C., eds. Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations. San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders; 2001:385–408.

94. Mailloux, Z. Goal writing. In: Smith Roley S., Schaaf R., eds. SI: Applying clinical reasoning to practice with diverse populations. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp; 2006:63–70.

95. Mailloux, Z., May-Benson, T., Summers, C.A., Miller, L.J., Brett-Green, B., Burke, J.P., et al. The issue is—goal attainment scaling as a measure of meaningful outcomes for children with sensory integration disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61(2):254–259.

96. Mailloux, Z., Mulligan, S., Roley, S.S., Blanche, E., Cermak, S., Bodison, S., et al, Verification and clarification of patterns of sensory intergrative dysfunction. Presented April 25. American Occupational Therapy Association Annual Conference and Exhibition Houston Texas, 2009.

97. Mailloux, Z., Roley, S.S. Sensory integration. In: Miller-Kuhaneck H., ed. Autism: A comprehensive occupational therapy approach. Rockville, MD: AOTA Press; 2002:215–244.

98. Maurer, D., Maurer, C. The world of the newborn. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

99. May-Benson, T. A theoretical model of ideation in praxis. In: Blanche E., Roley S., Schaaf R., eds. Sensory integration and developmental disabilities. San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders; 2001:163–181.

100. May-Benson, T.A., Cermak, S.A. Development of an assessment for ideational praxis. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61:148–153.