Interventions and Strategies for Challenging Behaviors

1 Describe reasons for behavior problems.

2 Explain how to prevent challenging behaviors from occurring.

3 Describe interventions for existing challenging behaviors.

4 Identify and describe specific strategies in behavior management.

5 Using case studies, discuss examples of behavioral intervention.

STRATEGIES FOR MANAGING DIFFICULT BEHAVIOR

Children with a variety of disability conditions may display challenging or inappropriate behaviors that interfere with daily life activities (Case Study 14-1). Behavior management strategies designed to prevent and reduce challenging behaviors are an important component of occupational therapy intervention for any child whose behaviors are interfering with occupational performance. This chapter introduces behavior management theories and presents strategies that have proven effective in preventing and reducing challenging or unacceptable behavior in children.

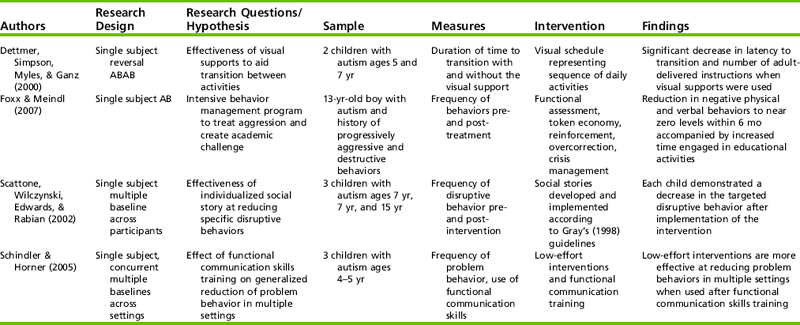

Much of what is known about challenging behavior and the strategies to facilitate behavior change has emerged from the fields of education and psychology. Robust research from these professions provides a wealth of knowledge that occupational therapists can apply to help understand why challenging behavior occurs, how to prevent challenging behavior, and how to intervene when a child exhibits challenging behavior (Table 14-1).

TABLE 14-1

Selected Single-Subject-Design Studies of Behavior Management Interventions

Dettmer, S., Simpson, R. L., Myles, B. S., & Ganz, J. B. (2000). The use of visual supports to facilitate transitions of students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15, 163-169; Foxx, R. M., & Meindl, J. (2007). The long term successful treatment of the aggressive/destructive behaviors of a preadolescent with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 22, 83-97; Scattone, D., Wilczynski, S. M., Edwards, R. P., & Rabian B. (2002). Decreasing disruptive behaviors of children with autism using social stories. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 535-543; and Schindler, H. R., & Horner, R. H. (2005). Generalized reduction of problem behavior of young children with autism: Building trans-situational interventions. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 110, 36-47; Gray, C. (1998). Social Stories and comic strip conversations with students with Asperger’s syndrome and high functioning autism. In E. Schopler, G. Mesibov & L. Kunce (Eds.), Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism? (pp. 167–198). New York: Plenum Press.

Behavior Happens

Behavior is an expressive act by an individual that can have many different forms and meanings. Whether a certain behavior is appropriate and acceptable is dependent on the context and contextual norms for the given situation. For example, in a public school building it would be inappropriate and unacceptable for a student to run out of a classroom onto the playground when the teacher passes out a work assignment; however, the same behavior would be appropriate and desirable in response to a ringing fire alarm. In turn, it is considered inappropriate and unacceptable for a child to scream and withdraw when his dinner plate loaded with green beans is placed on the table, but screaming and withdrawal are acceptable and possibly even anticipated when a child receives an immunization shot. As dynamic organisms with constantly active neurological, physiological, and physical systems, human beings interact with environments, materials, and other dynamic organisms. With so many variables at play, the possibility of a mismatch between two or more variables is likely. When such a mismatch occurs, undesired or inappropriate behavior may be exhibited.21

Inappropriate behavior can take many forms. Passive behaviors such as noncompliance, withdrawal, avoidance, inattention, or lack of response are not overtly disruptive but still interfere with occupational performance and participation. Active behaviors such as direct refusal to engage, opposition, aggression toward people or property, or self-injurious behavior not only interfere with occupational performance and participation but can also be disruptive or harmful. Both passive and active forms of inappropriate behavior can be difficult to manage.

Children exhibit challenging and inappropriate behaviors for many reasons. Some of these are internal and emerge from a lack of skill or ability to perform in a desired manner. Other reasons are related to external factors. Box 14-1 identifies some of the internal and external factors that influence behavior.

Purposes

To effectively manage difficult behavior, it is critical to remember that all behavior serves a purpose. Decades of research has identified three primary purposes of challenging behavior: (1) obtaining a desired object or event, (2) avoiding a situation, or (3) escaping from an undesired object, event, or demand.9 The purpose of a given episode of challenging behavior can be accurately identified only by the person executing the behavior or through careful analysis of those factors that maintain and strengthen the behavior. However, while a challenging behavior is being displayed, the individual likely is not in a state in which he can articulate the purpose of the behavior. This can be problematic for others who are experiencing the effects of the behavior and who want the behavior to stop. Functional behavioral analysis (FBA) is a formal process for evaluating the factors influencing behavior including the antecedents (events occurring before and triggering the behavior) and consequences (events after the behavior that also serve to reinforce the behavior). An FBA can be resource intensive and often is reserved for situations in which extreme or dangerous behaviors are occurring. The formal FBA process is described later in the chapter. For less severe situations, the FBA can be conducted informally by determining mismatches between the person and the context that are in effect when the challenging behavior is being executed.

Being Prepared for Problem Behavior

A variety of general strategies can be implemented to help create a context in which challenging behaviors are less likely to occur and more readily managed if they do occur. The following methods are suggested as general approaches to being prepared for problem behavior. These strategies are recommended as first steps in working to reduce the possibility of problem behavior; as children become more skilled, it is appropriate to adjust the type, structure, frequency, and intensity of supports provided.

Ruling Out Pain or Illness

Children experiencing pain or illness can act out in a variety of ways.2 Pain-based behaviors can be especially difficult to identify in children who are nonverbal. Behaviors associated with pain or illness may have a sudden onset, be associated with a certain body position, be cyclic, or occur frequently for no apparent external reason. If behaviors appear to be associated with pain, the occupational therapy practitioner should work with others to determine whether the behavior is driven by pain and, if appropriate, should follow through with recommendations to remediate the source of pain.

Establishing Predictability and Consistency

Maintaining a consistent context in relation to schedule, environment, people, and demeanor helps to allay a child’s anxiety about what is going to happen next.8 When anxiety is diminished, the child has more resources available to direct toward self-management and productivity. Children are more successful when expectations, environments, people, and situations are familiar. As much as is possible, the occupational therapy practitioner should work to increase the known and decrease the unknown. Examples of strategies are scheduling activities in a similar order and location from day to day, keeping the physical arrangement and furnishings in the environment consistent, offering the same type of activities, establishing consistent social expectations, and arranging to have the same people interact with the child during the same activities.

Creating a Calm Atmosphere

Keeping the physical environment clean and organized creates a sense of order and predictability. Children know where to find desired items and they know which areas to avoid if there are items that are off limits. In addition, maintaining a calm demeanor when mishaps occur can help to minimize chaos and preserve a sense of order. Children often react to the stress and anxiety displayed by others with a disorganization of their own behavior. When adults remain calm, a sense of order is maintained and the child is at ease.

Attending to Appropriate Behaviors

It has been said that for every negative comment, a child should hear at least eight positive comments.11 Adults should consistently reward and reinforce appropriate behaviors by attending to them, complimenting the child on his behavior, and identifying specifically what the child did that was appreciated. Specific feedback can increase the child’s awareness of the behaviors that are desired. Although general feedback can help a child build confidence in his ability to produce desired behaviors, specific feedback helps the child know exactly what to do the next time and increases the likelihood that the desired behaviors will occur again.

Using “Do” Statements

Similar to providing specific feedback, using “do” statements tells a child exactly what is desired. Rather than telling a child “Don’t pull Susie’s hair,” the occupational therapy practitioner rephrases the statement to direct the child to do a behavior that is desired: for example, “Use your hands for nice touching.” In contrast with the “don’t” statement, the “do” statement appeals to the child’s desire to please and helps to keep a positive atmosphere. Modeling the instructed behavior while saying the instruction helps to reinforce what is being communicated.

Keeping Perspective

Challenging behavior happens despite preventive measures. As children learn and grow through new stages of development and independence, they continually seek to discover where limits exist, where their capabilities lie, and what they are allowed to do. It is important for the practitioner to be prepared to respond whenever the challenging behavior occurs, so that expectations for appropriate behavior are quickly and effectively re-established.

BEHAVIOR MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Three primary approaches to managing challenging behavior are presented in this chapter: (1) preventing challenging behavior from occurring, (2) supporting desired behaviors, and (3) intervening when challenging behavior already exists. Strategies associated with each of these approaches are discussed in this section.

Preventing Challenging Behavior

Strategies for preventing challenging behavior are similar to the general strategies for supporting appropriate behavior. However, these strategies can be very effective when a child is known to have a repertoire of challenging behaviors and the goal is to prevent those behaviors from emerging.

Minimizing Aversive Events

Children often demonstrate inappropriate behaviors in response to events that they find aversive (Case Study 14-2).9 To minimize aversive events, situations and scenarios must be perceived through the child’s eyes. In other words, the occupational therapy practitioner should think about what it is that the child finds aversive. Often these are things that adults or other children do not consider problematic. Careful consideration of a particular child’s temperament, personality, likes, dislikes, skills, abilities, and sensory processing tendencies can be helpful in identifying those conditions and events that the child finds aversive. When an aversive condition is identified, minimizing the frequency, intensity, or duration of the condition can help to reduce the child’s reactive behaviors. If the correct events or conditions are not identified and addressed, no change in the behavior should be expected.

Sharing Control

Children often have very little control over their environments and the situations that surround them throughout the day. By allowing the child to choose activities, determine the order of events, or contribute his ideas about what should happen, the occupational therapy practitioner can instill a sense of value and build self-esteem. The experiences of making acceptable choices, contributing to a collaborative effort, and giving valued input not only help the child to feel important but can foster a sense of commitment to the therapeutic relationship. In turn, this can create the desire to preserve the relationship through effective and appropriate behaviors.

Providing an Environment That Promotes Successful Engagement

Challenging behaviors often occur when a child is bored or unoccupied. Providing an environment that promotes engagement can reduce boredom and thereby reduce occurrences of unacceptable behavior.10 Environments that promote engagement offer both structured and unstructured activities that are appropriate to the child’s level of development, are enjoyed by the child, and allow the child to experience success. Supplies and materials should be readily available to the child in locations that allow independent access. Strict rules about how and where materials are used should be relaxed to allow creativity and ingenuity. A child who is dynamically engaged in productive activity is less likely to engage in inappropriate or unacceptable behaviors.

Increasing Communication Effectiveness

Children who do not have an effective means of communication often use behavior to deliver a message. Messages about pleasant experiences or enjoyable activities may be communicated through a smile, hug, or clapping. However, messages about pain, an undesired activity or location, or an unpleasant situation may be communicated through a variety of inappropriate methods such as screaming, hitting, throwing, or destroying property. Being attentive to a child’s efforts to communicate is a first step in preventing situations that lead to frustration with communication barriers. Providing a means for the child to express both positive and negative messages effectively and efficiently can reduce inappropriate behaviors associated with lack of functional communication.6 Working with a speech-language pathologist to identify and implement the most effective and appropriate communication system is highly recommended. Strategies that can be helpful include using physical gestures or sign language and exchanging written symbols or icons. Strategies should be appropriate for the child’s ability level and should be portable for easy accessibility in all environments and situations.

In addition to providing an effective means for the child to communicate, it is equally important that the child receives and comprehends messages directed to him. This responsibility often falls to the speaker because many children are not able to express that they do not understand a message. Awareness by the receiver that a message has been communicated but not understood can be very frustrating. When the message is not acted on, the sender becomes frustrated at the lack of response. The receiver is not only at a loss to decipher the message, but may also receive verbal and/or nonverbal communication about the sender’s growing frustration. This scenario can result in increased anxiety, which may lead to behavioral outbursts. Using simple language to convey messages, allowing additional time for processing of information, and supplementing verbal information with gestures or visual information can increase the possibility that messages are received and understood by the child, reducing the likelihood of frustration and resulting behavioral reactions.14

Clarifying Expectations

When activities or schedules are similar from day to day, assumptions may be made that expectations are known. Children, while sensing the comfort of a familiar environment, schedule, and social structure, do not necessarily attach performance expectations to environments or situations. Uncertainty about what is expected may lead the child to unknowingly act in inappropriate ways or to act out to test the limits. Many children respond best when rules are clearly established and limits are defined. Explicitly communicating expectations about what the child is supposed to do and how he is expected to act can alleviate any misconceptions or misunderstandings and promote the child and therapist having the same expectations.21

Supporting Self-Regulation

Many children who demonstrate challenging behavior also have difficulty managing responses to environmental stimuli (see Chapter 11 on sensory integration). Ambient noise, flickering lighting, constant movement of others, inadvertently being bumped, and other unpredictable or intense environmental stimuli can be anxiety-producing for persons who respond intensely to these stimuli. The result can be physiologic over-arousal such that the individual’s sympathetic fight-or-flight response occurs. This response can manifest as behaviors such as aggression toward others, violence, self-injurious behaviors, or immediate and intense withdrawal from the situation. For these children, disorganized behavior may be a precursor to problem behavior.

The occupational therapy practitioner should watch for disorganized behavior and help the child to identify when behavior is becoming disordered. This may include informing the child of his disorganized behavior by specifically describing the behavior that was observed, identifying the context in which the behavior occurred, and describing what behavior would have been more appropriate to the context. In addition, the therapist should help the child develop a repertoire of more appropriate responses. Careful attention to and management of stimuli present in the environment can prevent the “fight, flight, or fright” response from occurring, allowing the individual to participate in the environment successfully. Box 14-2 identifies some suggested environmental modifications.

Matching Demands to Abilities

When performance demands exceed an individual’s abilities, that person can become frustrated, angry, avoidant, or aggressive. Conversely, when performance demands are too low and do not match or challenge an individual’s abilities, the person can become bored or uninterested in a task or activity. Either of these situations can result in challenging behavior as the individual expresses frustration with the mismatch between demands and abilities.10 Creating individualized expectations and designing the just right challenge for each child can help alleviate frustration and create a just-right match between each child’s performance demands and performance abilities.

SUPPORT POSITIVE BEHAVIOR

Strategies for supporting positive behaviors can be powerful tools in preventing situations that elicit problem behaviors. Some of the strategies are global and can be particularly useful for group situations in which more than one child requires assistance in managing appropriate behavior.19 Other strategies are individualized to a particular child. All of the strategies should be implemented consistently and predictably to create a context that supports the child’s ability to be successful.

General Strategies

Sensory input is an inherent part of life. Every experience and situation is saturated with sensation. Sensory information is received, interpreted, and managed by the central nervous system through a variety of chemical and electrical mechanisms. The central nervous system produces behavioral and emotional responses to this input. When an individual’s processing of sensory information is ineffective or inaccurate, erratic behaviors that are inappropriate to the context or situation can be displayed.1 These behaviors can take many forms. Often the behaviors can be identified as sensation-seeking or sensation-avoiding.5 Sensation-seeking behaviors result in increased quantity or intensity of sensory input to the nervous system. In contrast, sensation-avoiding behaviors result in a decreased quantity or intensity of sensory input to the nervous system. In and of themselves, sensation-seeking and sensation-avoiding behaviors are not inappropriate, but they may occur with inappropriate intensity, at inappropriate times, without regard for safety of others or the environment. By being aware of and taking efforts to meet an individual’s sensory needs, such situations can be avoided, allowing the individual to have greater success in interacting with the people, objects, and situations around them. This can be accomplished through a variety of strategies ranging from intense one-on-one intervention to a range of sensory-based strategies that are embedded in the daily routine. An example of addressing challenging behavior by meeting sensory needs is presented in Case Study 14-3. In addition, see Chapter 11 for a discussion of sensory integration dysfunction and strategies to meet sensory needs.

Building New Skills

Children who have deficits in performance areas can become frustrated with the frequent experience of poor performance or lack of success. As mentioned before, frustration can lead to demonstration of undesired behaviors as a way of expressing or dealing with the frustration.12 Thus, it is important that occupational therapists incorporate efforts to build new skills into their intervention plans. When developing the intervention plan, those skills that appear to pose the greatest barriers to independence in self-care, physical mobility, play, or education are often prioritized. However, it also is important to include development of skills that will enable the child to experience success in the regular daily occupations of social interaction and contextual participation. Box 14-3 identifies skills that are easily overlooked but are important to social participation. These should be incorporated into the occupational therapy intervention plan in an effort to build new skills and reduce frustration and the resulting problem behaviors.21

Specific Strategies

Increasing Compliance Through Contingency Methods

Many children resist engaging in tasks that they do not enjoy. Resistance can take many forms including, but not limited, to withdrawal, refusal, avoidance, and aggression. Contingency methods such as offering rewards or using a token economy can help to elicit participation in nonpreferred activities. Contingency methods are based on the principle of allowing access to a desired event contingent upon performance of or compliance with something else. For example, during intervention a child who enjoys blowing bubbles would be allowed to play with bubbles only after he completed a therapist-directed task such as pencil-paper work. Contingency approaches are commonly used in everyday life for children—access to outdoor play is not granted until the child puts on his coat; dessert is not served unless the child finishes her dinner. By withholding the desired item or activity until after the child completes the mandatory task, motivation is increased and compliance is gained.

Token Economies

Token economies are similar to withholding strategies, but are more complex. A system in which the child earns tokens for desired behaviors is established and taught. Examples of behaviors that are reinforced are compliance with a rule, completion of a certain task or part of a task, and keeping hands out of mouth. The tokens can be exchanged for privileges such as 2 minutes of play with a preferred toy, a piece of candy, or the opportunity to play a game on the computer. In essence, certain privileges are withheld from the child until he has sufficient tokens to buy them. The tokens are earned through performance of desired tasks, engagement in prescribed activities, or demonstration of appropriate behavior. In establishing the token economy, the specific behavior for which tokens can be earned should be specified, as should the number of tokens each behavior is worth. For example, a child might earn one token for engaging in seat work for 3 minutes without needing redirection, or earn two tokens for spontaneously sharing art supplies with another child. In addition, the privileges or items that the child can purchase with the tokens and the cost of each should be established at the outset of establishing the token economy.

Token economies can be very simple, involving merely the earning of tokens and purchasing of rewards, or they can be made more complex by incorporating tokens given for undesired behaviors (Case Study 14-4). In this system, the child earns one color of token (often green or white) for desired behaviors and another color (often red) for undesired behaviors. The tokens for desired behavior have purchasing value and those for undesired behavior decrease purchasing value. For example, a child might earn one green token for each 2 minutes that he remains seated during independent work time and one red token each time he moves out of his chair. At the end of a 10-minute work period, the child has four green tokens and two red tokens. Each red token cancels out one green token, leaving the child with two tokens for that period of time.

Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is a specific strategy that has been established as a powerful behavior change technique. Positive reinforcement is the contingent presentation of a type of consequence that, when presented immediately after a behavior, increases the probability of that behavior occurring again.17 In other words, a consequence that strengthens a behavior functions as a positive reinforcer for that behavior. Consider the mother who gives in and hands her child a cookie to stop the crying that began when the mother first denied the child’s request for the cookie. Though the mother’s purpose in giving the cookie was to stop the crying, the crying resulted in his obtaining a desired object. In other words, from the child’s perspective, the crying worked. The likelihood that the child will behave in the same manner in the future (i.e., cry) has been increased by the positive reinforcer (obtaining the cookie). The power of positive reinforcement to effect behavior change has more than 40 years of empirical support15,16,23–25; however, occupational therapy practitioners typically are not trained in these techniques.22 Strategic and effective use of this method could increase desired behaviors and reduce challenging behaviors, thereby supporting client engagement in therapeutic activities.

Alternate Preferred and Nonpreferred Activities

At times, all children need to participate in or complete tasks or activities that they do not enjoy. Attempts to gain the child’s compliance in a nonpreferred task can lead to opposition, withdrawal, or outright refusal. If the adult keeps pressing the child to comply, challenging behaviors can escalate. One strategy for gaining compliance is to alternate the nonpreferred activity with one or more preferred activities. This strategy is similar to the contingency approaches in which a desired activity or event is withheld until the child performs a therapist-directed task. To implement this strategy successfully, the nonpreferred activity should seamlessly follow the preferred activity and should be presented in a matter-of-fact manner that does not highlight the child’s lack of preference for the activity. By strategically and seamlessly sequencing the nonpreferred activity to come just after a preferred activity, the child is more likely to comply because the activity seems to flow from the one he just completed (Case Study 14-5).

Addressing Transitions

Transition between activities or environments can be particularly problematic times during which challenging behaviors emerge. Some practical strategies can support children during transitions and help to minimize noncompliance or refusals.

In school situations, the classroom schedule often dictates when a transition needs to occur. Adults have strategies such as watching the clock and having awareness of how much time has passed, which helps them anticipate a pending transition. Children do not have the same strategies, and transitions can appear to be arbitrarily imposed.

A transition routine can help to set the stage for a positive transition. Transition routines consist of using the same set of events each time a transition needs to occur. Singing a particular song or using a hand-clapping pattern are simple, distinct events that can be used to signal transitions. Using the same strategies for each transition provides familiarity, establishes context, and communicates expectations, all of which can help children transition successfully.

Timers provide an objective signal that something is about to occur.7 Because once it is set, a timer operates independently of an adult, the implication that changes are arbitrarily imposed by the adult is reduced. To implement use of a timer, the occupational therapy practitioner shows it to the child and informs him of what will happen (e.g., “The timer will make a beeping sound. When you hear the beeping sound, it will be time to clean up the blocks and come to the table for snack.”). The practitioner trains the child in how to turn the timer off. When the timer signals, the practitioner cues the child that the timer is beeping, helps the child turn off the timer, and reminds the child what the sound meant (Case Study 14-6).

Once use of the timer is established, it can be applied in a variety of contexts and situations. Children can learn to operate the timer themselves as a way to self-monitor use of time and compliance with time limits. Alarm clocks can be used in a similar manner as timers to indicate events that occur at a specific time of day such as time to go to the bus stop, time to get ready for bed, or time to leave for an appointment.

Another excellent method of supporting successful transitions is the use of visual schedules.4 These are particularly useful in situations where the schedule remains relatively similar from day to day or week to week. Either picture icons or word cards can be arranged on a schedule board to represent the sequence of activities or events that is going to occur. Children can follow the visual representation of the sequence. Depending on a given child’s abilities, he or she can learn to use the visual schedule independently, consulting it when one activity is completed or when a transition is indicated. Some visual schedules merely represent activity sequences with no time allotted. Other schedules are time-based and indicate day of the week, time of day, and the activity that will be occurring. Many visual schedules use removable cards so that the schedule can be modified easily if the schedule changes. Some schedules are posted on poster board mounted to the wall; others are secured in a binder or notebook that is easily transported from one setting to another. The form of the schedule and the amount of support given to the child in using the schedule are individualized to the child’s capabilities.

General Support Strategies

Many challenging or inappropriate behaviors can be ameliorated through the use of general positive strategies. Providing extra time for a child to process a verbal instruction or organize an appropriate response to a stimulus can alleviate anxiety and stress and the resulting behavioral reaction. Providing encouragement that communicates belief in the child’s ability to succeed can improve self-esteem and a sense of self-worth.18 Giving explicit instructions in how to approach or complete a task can alleviate fears of failure that may cause a child to withdraw or disengage from an activity. Providing specific feedback about the child’s efforts and what could be done differently next time can also build confidence and motivate a child to try again rather than walk away from a task with a feeling of despair. These strategies are examples of therapeutic use of self. The therapist uses the therapist-client interactions strategically to support the client in whatever challenge he or she is experiencing and to communicate belief in the individual’s ability to achieve his or her desires. Effective therapeutic use of self leads to a partnership between the therapist and the client that is empowering and encouraging.20 The power of these experiences can help to prevent misbehaviors that are associated with feelings of despair and low self-esteem.

INTERVENE WHEN CHALLENGING BEHAVIORS ALREADY EXIST

The best practice approach to managing challenging and problematic behaviors that already exist combines FBA with a positive behavioral support (PBS) plan.13 This comprehensive approach is a highly structured, dynamic process that addresses the problem behavior within the natural context. The FBA is a 5-step process consisting of (1) team building and goal setting, (2) functional assessment of the behavior, (3) hypothesis development, (4) development of the comprehensive support plan, and (5) implementation and outcome monitoring of the plan including refining the plan as needed.3 Occupational therapists may be part of the FBA process because they often have personal knowledge of the client and direct experience with the behavior of focus. Each of the five steps of the FBA process is described briefly in the following paragraphs.

The first step of the FBA process is to gather a team of individuals who will collaborate to work together for the child’s best interest. Ideally, the team includes the child’s parents or caregivers as recognized experts on the child and as partners in the intervention process. Together with the caregivers, the team works to first identify desired outcomes for the child.3 Conversation and planning centers around understanding the child as a “whole” person, including the child’s capacities and areas needing further development. This process creates a foundation upon which the intervention and support plans are built.

Step two involves the comprehensive functional assessment of the specific behavior. Efforts focus on clearly describing the challenging behavior, the context(s) in which it occurs, the antecedents and consequences that maintain the behavior, and the functions of the behavior. The goal of this step is to understand the purpose of the behavior and when the behavior is most and least likely to occur. Data collection is the best method for understanding the purpose of the behavior and the events that maintain the behavior. Data can be gathered by interviewing people who have direct knowledge of the child and experience with the behavior, observing the child where and when the behavior is most likely to occur, reviewing records in which the behavior has been documented, and gathering information about contextual variables such as health or changes in other environments or activity schedules.

The third step in the FBA process is to develop hypotheses about the behavior including the antecedents (factors that trigger the behavior), consequences (responses to the behavior), and communicative function of the behavior (request something or avoid/escape from something). Hypotheses statements are generated based on the information gathered in step two.

Fourth, a comprehensive behavior support plan is developed. The plan itself has four elements: (1) a functional assessment of behavior provides a foundation for the intervention plan, (2) multiple intervention strategies are used, (3) the plan is applied throughout the day, and (4) the elements of the plan are consistent with the values and resources of the child receiving support and the persons providing support.13 The collaborative effort of the team to gather data about the behavior and develop hypotheses about the function and reinforcing events surrounding the behavior are used to understand the behavior and the functional purpose it is serving for the child. This understanding is used to develop the intervention component of the plan, which includes strategies aimed at preventing the challenging behavior from occurring and strategies aimed at helping the child develop new skills that effectively and efficiently achieve the same function as the challenging behavior. The new skills are taught to the child as replacement strategies for the challenging and undesired behavior. The plan also includes contingencies for both the challenging and the replacement behaviors. The contingencies for demonstration of the replacement behavior are designed to reinforce and strengthen use of the new behavior, whereas the contingencies for the challenging behavior are designed to discourage its use.

The final step of the PBS process is implementation of the plan and measurement of outcomes. Once the plan is developed, it is tested for goodness of fit with the personal, physical, and social contexts of the child, family, and other service providers to ensure that all persons involved in implementing the plan are equally comfortable using the plan in their respective situations. Ensuring goodness of fit is a critical step in increasing the likelihood that the plan is used. As the plan is implemented, the team evaluates the effectiveness of the plan in producing the desired results: reduction of the challenging behavior and production of the replacement behaviors. The team meets periodically to review plan effectiveness and the child’s progress. Modifications and adjustments are made as needed followed by implementation and monitoring of the revised plan (Case Study 14-7).

SUMMARY

Challenging and inappropriate behaviors are demonstrated by children with a wide range of developmental disabilities and can interfere with engagement in occupation, prevent participation in context, and create situations that are potentially harmful. When problem behaviors exist, reducing the problem behavior should be a primary focus of occupational therapy intervention. Effective management of challenging behavior includes not only improving an individual’s behavioral competence but also creating contexts that support positive behaviors and intentionally managing consequences. Occupational therapy practitioners have knowledge and skills in task analysis, human behavior, and occupational engagement, enabling them to effectively analyze problem behavior, develop behavioral intervention plans, and implement behavior management strategies.

REFERENCES

1. Baker, A.E., Lane, A., Angley, M.T., Young, R.L. The relationship between sensory processing and behavioural responsiveness in autistic disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:867–875.

2. Bauman, M. Autism: Emotion and behavior—is it all in the brain? Paper presented at R2K: Research 2008 Sensory Integration. Long Beach, CA: Emotions, and Autism, 2008.

3. Buschbacher, P.W., Fox, L. Understanding and intervening with the challenging behavior of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2003;34:217–227.

4. Dettmer, S., Simpson, R.L., Myles, B.S., Ganz, J.B. The use of visual supports to facilitate transitions of students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2000;15:163–169.

5. Dunn, W. The impact of sensory processing abilities on the daily lives of young children and their families: A conceptual model. Infants and Young Children. 1997;9(4):23–35.

6. Durand, V.M., Carr, E.G. An analysis of maintenance following functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:777–794.

7. Ferguson, A., Ashbaugh, R., O’Reilly, S., McLaughlin, T.F. Using prompt training and reinforcement to reduce transition times in a transitional kindergarten program for students with severe behavior disorders. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 2004;26:17–24.

8. Flannery, K.B., Horner, R.H. The relationship between predictability and problem behavior for students with severe disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1994;4:157–176.

9. Foxx, R.M. Twenty years of applied behavior analysis in treating the most severe problem behavior: Lessons learned. Behavior Analyst. 1996;19:225–235.

10. Foxx, R.M., Meindl, J. The long term successful treatment of the aggressive/destructive behaviors of a preadolescent with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2007;22:83–97.

11. Grazier, P.B., Starving for recognition: Understanding recognition and the seven recognition do’s and don’ts. EI Network 1995. Retrieved October 9, 2008, from, http://www.teambuildinginc.com/article_recognition.htm.

12. Horner, R.H. Positive behavior supports. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2000;15:97–105.

13. Horner, R.H., Carr, E.G. Behavioral support for students with severe disabilities: Functional assessment and comprehensive intervention. The Journal of Special Education. 1997;31:84–104.

14. Horner, R., Carr, E., Strain, P., Todd, A., Reed, H. Problem behavior interventions for young children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32:423–446.

15. Koegel, R.L., Koegel, L.K., Frea, W.D., Smith, A.E. Emerging interventions of children with autism: Longitudinal and lifestyle implications. In: Koegel R.L., Koegel L.K., eds. Teaching children with autism: Strategies for initiating positive interactions and improving learning opportunities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 1995:1–16.

16. Koegel, R.L., O’Dell, M., Dunlap, G. Producing speech in nonverbal autistic children by reinforcing attempts. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1988;18:525–538.

17. Malott, R.W., Malott, M.E., Trojan, E.A. Elementary principles of behavior, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2000.

18. McMinn, L.G. Growing strong daughters. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2000.

19. OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavior Supports and Intervention School-wide PBS, 2008. Retrieved on December 23, 2008 from, http://www.pbis.org/schoolwide.htm.

20. Taylor, R.R. The intentional relationship: Occupational therapy and use of self. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 2008.

21. Watling, R. Interventions for common behavior problems in children with disabilities. OT Practice. 2005;10:12–15.

22. Watling, R., Schwartz, I.S. The issue is: Understanding and implementing positive reinforcement as an intervention strategy for children with disabilities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;58:113–116.

23. Williams, J.A., Koegel, R.L., Egel, A.L. Response-reinforcer relationships and improved learning in autistic children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:53–60.

24. Wolf, M., Risley, T., Mees, H. Application of operant conditioning procedures to the behaviour problems of an autistic child. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1964;1:305–312.

25. Zannolli, K., Daggett. The effects of reinforcement rate on the spontaneous social initiations of socially withdrawn preschoolers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:117–125.

CASE STUDY 14-1

CASE STUDY 14-1