Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Community Participation

Kathryn M. Loukas and M. Louise Dunn1

1 Define instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) and community participation for children and youths.

2 Describe how participation in IADLs and community participation contributes to occupational development for children and youths.

3 Describe development of IADLs and community participation.

4 Describe occupational performance by developmental age ranges and disability.

5 Describe personal and environmental influences.

6 Identify and apply professional reasoning, evaluation procedures, and intervention approaches for IADLs and community integration.

7 Describe, apply, and integrate evidence-based and occupation-centered intervention approaches to enhance IADL and community participation for children and youth.

8 Evaluate and synthesize information about the development of IADLs and community participation for children/youth through analysis of case studies.

INTRODUCTION

Peter is a 12-year-old boy who has autism. His parents are worried about how he will take care of himself. They are unsure about his role in the home and how much to ask of him. At school, the occupational therapist had taken a sensory motor approach to Peter’s occupational therapy, yet she now sees the need for more skills in independent living for Peter. The education team wonders how much to include Peter in life skills and vocational programming.

Mary is a 16-year-old girl who was in a serious car accident that left her with left-sided hemiplegia and cognitive challenges secondary to a brain injury. She is now struggling with activities she used to find routine. She is unsafe in the kitchen, she has difficulty handling money, and her poor social skills make it difficult to make friends. Mary and her family are concerned about her future and wonder how she can regain the skills she needs for community living.

John is an 8-year-old boy with attention deficit disorder. His parents find it extremely challenging to involve him in household tasks, so they organize and manage his belongings and space. He has extreme difficulty paying attention in sedentary activities. John needs structure and guidance to participate in any community-based activity. John is interested in boy scouts and soccer, but his family has not allowed him to participate because of his behavior.

Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) are the more complex aspects of daily living that children and youth develop as they reach adolescence and begin to participate in the community with more autonomy. These activities include care of others, care of pets, child rearing, use of a communication device, COMMUNITY MOBILITY, financial management, health management and maintenance, home management, MEAL PREPARATION AND CLEAN-UP, shopping, and safety procedures and emergency responses (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008). Occupational therapists are experts in IADLs, task analysis, and independent living.

Children initially acquire more skill with IADLs when they reach adolescence and begin to participate in the community with more autonomy. They continue to develop competence in these activities through adolescence into young adulthood. IADLs and community participation include activities that promote self-determination, self-sufficiency, health, and social participation for children/youth of all abilities. IADL competence could be categorized as part of the “magnificent mundane”11 and is noted more by its absence than its presence. The magnificent mundane refers to the everyday presence of these tasks and reflects the tacit manner in which children/youth learn and understand their roles in these occupations. As preparation for independent living in the community, IADLs may include home management (e.g., clothing care, cleaning, and household maintenance), shopping and money management, meal preparation and cleanup, COMMUNITY MOBILITY, health maintenance (e.g., taking medications, exercise and nutrition), care of pets and care of others, and safety procedures and emergency responses.1

An integral relationship exists between IADLs and community participation. For example, shopping is an IADL task that requires interaction with others in the community. Methods for learning to participate in the community may be tacit, such as learning through observation and assisting with shopping, or more explicit, such as finding and enrolling in community activities. Community participation includes social, play, and leisure activities with peers in the community and neighborhood and structured activities within the neighborhood and community.6,43

Recent studies contribute to our understanding of the diverse and complex challenges involved in preparing youth for independent/community living. Youth and adults with physical disabilities reported that they lacked opportunities to direct their health care services by making their own appointments and asking questions of medical and health personnel.25,32 Adults with physical disabilities reported dependence in shopping, home cleaning, laundry, and use of public transportation.3 Youth in foster care may lack knowledge and experience with independent living, especially safety and home and health maintenance.46,49 Children and youth with traumatic brain injury (TBI) often lack opportunities to engage in household tasks and community activities such as shopping and recreational activities.7

This chapter provides an overview of the development of IADL skills and community participation, and a description of models that guide practices to promote competence in IADLs and full participation in community living. It further explains how emotional well-being, health, peer relations, and life satisfaction are associated with competence and independence in IADL and community living skills. Evaluation and intervention are discussed and illustrated using case examples.

OCCUPATIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF IADL AND COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

Successful independent/community living is measured by outcomes related to employment, residing in the community, and community participation. IADLs are embedded in community living.

A large longitudinal study demonstrated that 2 years after leaving school, youth with special needs were more likely to be unemployed, live with their parents, and lack engagement in community activities with peers than youth without disabilities.9 In a second longitudinal study, youth with special needs showed increased employment and engagement in community activities; however, their involvement lagged behind that of their peers without disabilities.80 Youth with special needs continued to lag behind nondisabled peers in residing with others or alone in the community.

Self-determination has been identified as a factor that promotes independent community living. Defined as “a combination of skills, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors that enable a person to engage in goal-directed, self-regulated, autonomous behavior,”20 self-determination encompasses many of the behaviors and attitudes often referred to as life skills that are both innate and learned.44 These skills include managing personal care and health needs, taking care of one’s belongings and space, managing home repairs, arranging transportation, and living interdependently with others. Opportunities to develop problem-solving skills, understand one’s own strengths and limitations, and make choices are critical to developing these skills. In fact, youth with mild intellectual and/or learning disabilities who have higher self-determination had greater employment rates, earned higher wages, and had more community involvement at 1 and 3 years out of school than similar youth with low self-determination.82,83

Late Adolescence (16 to 18 Years)

By late adolescence, youth are more autonomous and show greater breadth in their IADLs and community participation. Many spend most of their time outside the home, driving or taking public transportation, working a part-time job or volunteering, shopping, managing money, and maintaining a healthful regimen (e.g., taking responsibility for medications, exhibiting awareness of healthful behavior with partners).25,46,66,72 At this age, many youth prepare hot and cold meals, help with cleanup, and manage their laundry. Box 17-1 provides guidelines about IADLs and community participation expectations for older adolescents.

Physical skill levels may limit opportunities to engage in IADLs tasks and community participation for many youth with physical disabilities; but with adaptations and accommodations, many become competent. Behavioral concerns such as lack of confidence, dependency, or weak social skills may also influence task performance of youth with physical disabilities, especially in community activities.45

Youth with acquired brain injury, especially when the brain injury was incurred at a young age, often have cognitive, behavioral, and or social impairments that influence their IADLs and community participation. They often require greater assistance with memory, problem solving, and self-management to initiate and complete tasks, sustain focus on tasks, and interact with others when completing work than they do with mobility.19 Youth who experience an acquired brain injury are likely to need special coaching and assistance to manage the social demands of using public transportation on their own when they need to attend and interact with others.

Youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may do well with household tasks such as making a snack, yet they have difficulty with tasks that require more interaction such as shopping. These youth are likely to have greater difficulty with tasks that involve relating to others, as would be needed to manage health care needs. Engaging in structured and unstructured leisure activities such as team sports or volunteer activities and going to the mall are challenging for youth with ASD.33 Finally, acquiring initiative to do IADL tasks and engage in community activities may be difficult for many youth with disabilities.

Early Adolescence (12 to 15 Years)

For young adolescents, teachers and parents emphasize not only learning from academics and vocational exploration but also home and health management, shopping and meal preparation, and community participation.25,66,72 School programs attempt to establish not only adolescents’ independence but also their ability to work interdependently with others. Young adolescents have increased responsibility for caring for others, managing their laundry, preparing simple, hot meals, and preparing snacks.46,66,72 Technology, such as the microwave, cell phones, e-mail, and instant messaging/texting, increases young adolescents’ opportunities for communication and community participation. Box 17-2 provides guidelines about IADL and community participation expectations for young adolescents.

Youth with disabilities often need additional practice and opportunities to promote autonomy with IADLs and community participation.7,18 Young adolescents with physical disabilities may not direct others or seek assistance as needed with these IADL and community tasks. Some may be reluctant to express their lack of knowledge about how to prepare a meal and just wait until someone does it for them. In addition, cognitive/behavioral and social skill deficits may impede their autonomy in these areas.45 Lack of assertiveness may impede their willingness to engage in leisure and recreational activities.

Similar deficits at varying levels also impede participation and performance of youth with TBI, ASD, and learning and intellectual disabilities. Communication deficits and rigidity may make it difficult for young adolescents with TBI and ASD to do volunteer work or arrange rides to structured recreational activities. Lack of safety awareness and difficulty understanding the needs of others may make taking care of younger siblings or others difficult for young adolescents with TBI and ASD. Their insistence on sameness and lack of flexibility may make negotiating with others difficult, a skill needed in many recreational activities such as group hikes.

Middle Childhood (6 to 11 Years)

In middle childhood (6 to 11 years), formal learning opportunities related to IADL and community participation are limited unless children have significant intellectual disabilities. Children in the middle years prepare for future independent/community living through their engagement in everyday family, afterschool and community, and school activities.42,54 These occupations give children opportunities to make choices, solve problems, and identify interests and skills that help them develop self-determination, social skills, and performance competency.59,74,81

In middle childhood many children engage in family and household routines; however, diversity in what they do and with whom is common. Parents report that they expect their children to take care of their space and materials, help with cleanup after meals, prepare simple cold meals, help with putting away groceries, and care for siblings with supervision.16 As they engage in these tasks, children develop communication, cognitive, and social interaction skills (e.g., problem solving on encountering difficulty). Community activities include formal structured activities such as sports or music lessons, as well as informal unstructured activities such as riding bikes. Box 17-3 provides guidelines about IADL and community participation expectations for children of middle childhood age.

Physical, cognitive, and social functioning deficits may make it difficult for children with disabilities to develop the skills necessary to participate in these activities. For children with either physical and/or cognitive/behavioral disabilities, generalization of learning to different settings may require specific cognitive and behavioral strategies.62,64 Children with cognitive/behavioral disabilities such as attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may clean up after preparing food in a community setting yet not carry over this learning to their home life.30 Children with ADHD may use social skills during art activities at school yet have difficulty sharing materials and taking turns in afterschool creative art activities. Children with physical disabilities may participate in recreational activities by observing rather than doing.65 Some may not assist with IADLs such as setting or clearing the table because of the time it takes them to do these tasks or because their physical impairments limit their participation.

Children with TBI may not engage in family routines such as preparing simple cold meals and picking up shared areas because of their high need for coaching. Those with memory impairments will need continual practice and repetition to organize their belongings for school and non–school-related activities. Their attention deficits may impede their safety when crossing the street. Depending on severity, children with ASD may need assistance to focus and find items on the shelf at the supermarket. They may have tantrums and meltdowns at the supermarket or mall because of overstimulation by sounds, sights, and smells.

Preschool (3 to 5 Years)

In preschool, participation in home day care and community activities frequently occurs with supervision from caregivers or parents. Therefore, family involvement is essential to development of IADL and community participation.34,68,71

Availability of free play allows children the opportunity to identify interests, make choices, and learn how to share and take turns. In the Head Start program, much emphasis is placed on promoting self-determination by assisting children to identify when they need help and guiding them to solve problems on their own.24,71 Furthermore, children with and without disabilities are involved in many naturally occurring learning opportunities through community activities such as shopping, going to neighborhood playgrounds, attending library story hours, taking walks in the neighborhood, or participating in events at community centers.17 In the home, preschool children assist with many household tasks such as putting away their own toys, making their beds, putting away their clothes, helping to set the table, and preparing cold snacks.66 In many families, greater emphasis is on beginning to take care of oneself and one’s belongings than on taking responsibility for others.

Little information exists about IADL participation for preschool children with disabilities. For children with physical disabilities, opportunities to perform tasks such as picking up one’s toys, making choices about snacks, or pointing to items at the supermarket may provide ways to develop routines and be part of the family. Children with TBI may need coaching and positive supports to promote their ability to pick up their toys and make choices about snacks or community activities.

In summary, age and functional abilities contribute to the extent of children’s and youth’s participation and performance of IADL and community activities. IADL and community participation are both the means and ends for development of motor and process performance skills.

PERSONAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES ON IADLS AND COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

Multiple interrelated internal and external factors influence children’s and youth’s engagement in IADLs and community activities. The occupational therapist should address personal and environmental factors that may support or limit the child’s or youth’s participation in IADLs and community activities.

Personal Influences

Factors that are within children and youth include their interests, preferences, and motivation to engage in activities. Engagement in IADL and community activities requires interest and motivation. Initially, motivation may be promoted with external support; however, to continue to engage in tasks and use skills, children and youth must internalize reasons to do so.63 Internalization of reasons for performing IADL tasks may relate to increased responsibility and opportunities to do favorite activities or to earn money.10,31

Environmental Influences

Factors external to the child comprise five environmental or contextual areas: (1) the natural and built environment (physical context); (2) support and relationships (social context); (3) attitudes, values, and beliefs (cultural context); (4) assistive technology; and (5) service systems and policies.1,85 These factors can either support or limit children’s and youth’s participation IADL and community activities.

The natural and built environment (physical context) includes the sensory and physical qualities of the setting (e.g., noise, lighting, temperature, terrain, crowding), building design, and accessibility to materials.45 Within the home, access to different areas and materials supports participation of children and youth in family activities. In the community, buildings that have accessible entrances and activities on a flat terrain support inclusion of children and youth with physical limitations. Examples of barriers are homes without access to all areas and community centers with activities on multiple levels that lack ramps or elevators. Crowding (e.g., group size) and sensory aspects of the environment are potential barriers for children and youth with physical, sensory, cognitive, and intellectual disabilities.35,52,60 For children and youth with ADHD, ASD, and intellectual disability, the noise from people talking and the movement of people in a crowd may contribute to behavioral outbursts, anxiety, and aggression, thus decreasing their participation. Noise, visual stimulation, and crowding limit participation because these factors interfere with balance, mobility, and communication for children and youth with physical disabilities.52

Support and relationships (social context) are particularly salient factors that influence participation of children and youth in IADL and community activities. At home, support is crucial for participation with family members in everyday activities. Families provide children with opportunities and encouragement to learn household tasks such as mealtime preparation and care of common spaces. Modeling of task performance and discussion of tacit planning processes make learning and understanding these tasks more tangible to children and youth. For example, at home children can observe not only their parents but also their siblings. In addition, children may be mentors to their siblings and guides for their parents. As children mature, they may take on the role of caring for their siblings when parents are out of the home. In the community, children may begin by attending structured afterschool activities such as sports or recreation groups (Figure 17-1), or they may meet with peers to socialize at the mall. As they approach older adolescence, they may also take on roles as mentors at recreational centers or scouting events.

FIGURE 17-1 Adolescents participate in afterschool sports and recreation programs. From Cummings, N. H., Stanley-Green, S., & Higgs, P. [2009]. Perspectives in athletic training. St. Louis: Mosby.

The social environment for IADL participation may vary by setting (e.g., school, home, community, or work). At home, children might observe parents and siblings doing household tasks and attempt to model their actions. Short-term outcomes from participating in mealtime preparation and household tasks include promoting a sense of family and demonstrating positive health and social behaviors.16,53 Long-term outcomes include preparation for adult roles. Lack of support and diminished opportunities for participation in these mundane tasks can impede development of community living skills (e.g., such as the example of youth in foster homes46).

Cultural values and beliefs significantly influence opportunities for IADL and community participation. At home family beliefs about routines and perspectives on time allocation influence children’s and youth’s engagement in activities at home and in the community.21,26,78 For example, parents of Asian background tend to value academics and place much less emphasis on IADL activities and autonomy for their children.87 In contrast, Latino and Navajo families tend to focus on interdependency and promote engagement in household and IADL tasks.69

The value of interdependency versus autonomy may influence a family’s willingness to support the independence of a child or youth with a disability. Families from African American and Hispanic backgrounds are more likely to plan to have their children with developmental disabilities live with them when the children reach adulthood.5 These beliefs may also influence the opportunities to engage in IADL tasks and community activities for children and youth with disabilities. Parents of children with disabilities, particularly those from lower socioeconomic levels, were less likely to involve their children in household tasks and in interacting with others in the community.87 Values for engaging in interdependent activities also influence participation in household tasks. For example, parents of children with ADHD tend to emphasize household tasks that involve managing one’s own belongings with less focus on shared tasks such as helping at mealtimes.16

Community programs that include children and youth of all abilities are supports for community participation.52 Social stigma, bullying, and marginalization are barriers for children and youth with disabilities.45,52

Assistive technology, computers, online resources, and augmentative communication devices are supports used commonly with children and youth who have disabilities to promote their participation in IADL and community activities. Technology and online resources afford opportunities for children and youth of all abilities to connect with others. Information about community activities, employment, shopping, banking, meal planning, public transportation, and health are available online. A growing number of support groups for children and youth with many differing disabilities have set up websites that provide peer mentoring for learning how to live in the community and care for their own needs.

Examples of service systems that promote inclusion of children and youth with disabilities are inclusive aftercare and recreational programs, programs with adaptive equipment, and transportation. Policies, rules, and standards that govern these services ensure that they are accessible and enable optimal participation of persons with disabilities.45,85 For children and youth with disabilities, lack of transportation or length of time required to transition to programs can be a barrier to participation in community activities.35 Another barrier is the lack of policies and funding to cover costs of additional supports that may be needed for inclusion of children and youth with disabilities in out-of-school activities.35,60

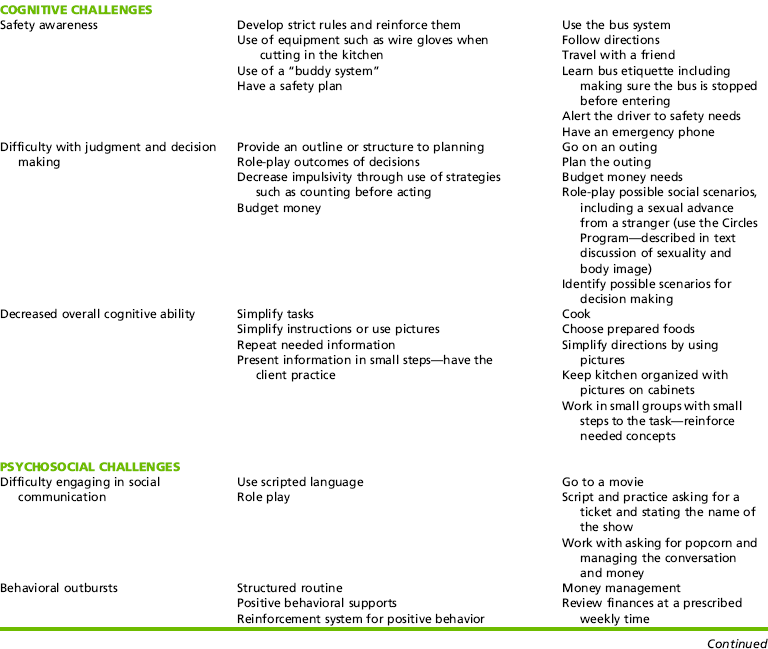

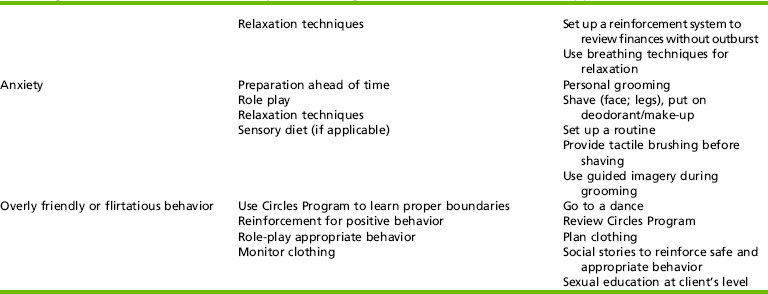

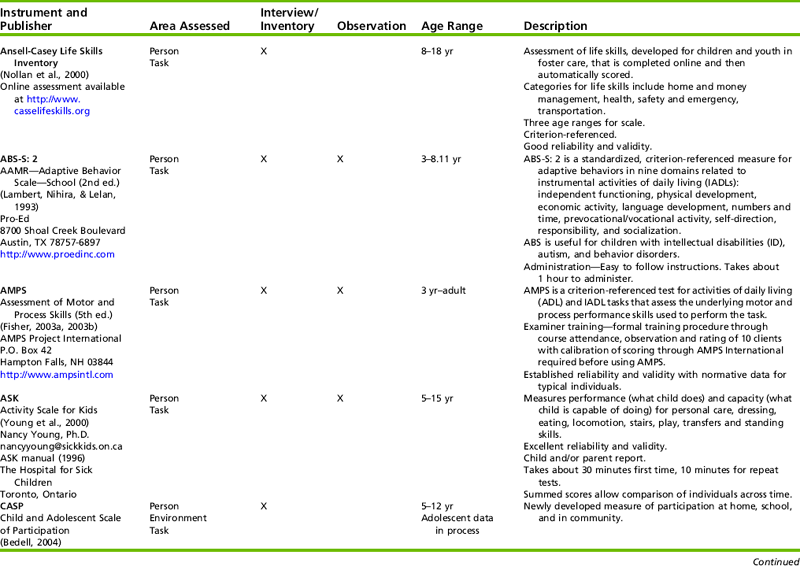

EVALUATION OF IADL AND COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

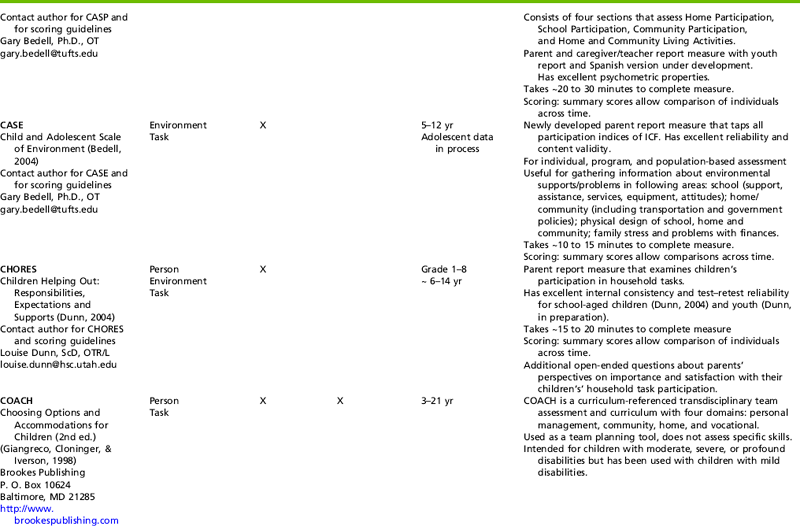

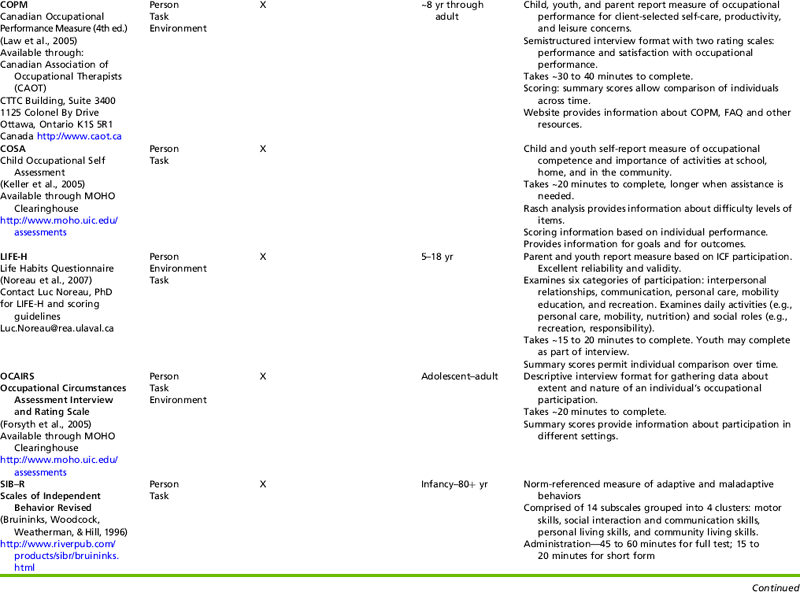

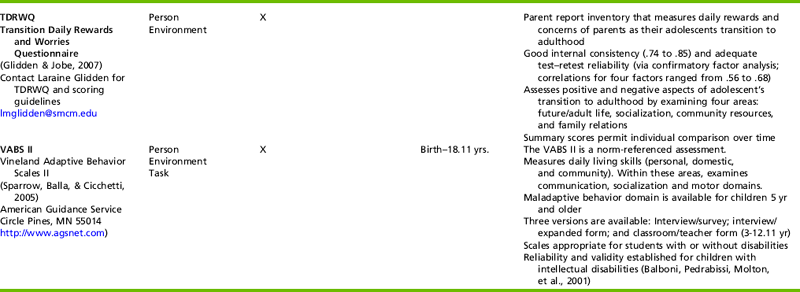

Children, youth, and their families or caregivers play key roles in the evaluation process. These individuals provide relevant information about the settings and contextual features where the children or youth engage in IADL and community activities. Providing youth with greater opportunities to engage in the evaluation process increases their autonomy and prepares them for decision making and management of their health, IADL, and community participation needs. Providing children, youth, and caregivers with opportunities to select or refuse assessments and choose where and when the evaluation is completed increases their investment in collaboration around intervention planning.27 Evaluation of IADL and community participation may include combinations of the following methods: observation, interview, inventory/questionnaire, performance measures, interest checklists, and chart review. The evaluation may be part of a school-based triennial evaluation required under IDEA and/or transition plan at the request of a pediatrician or health care practitioner, at the parent’s request, as part of a medical model assessment, or as part of community models such as foster care. Evaluations may be conducted individually with the child/youth and caregiver, as a team evaluation, or as part of a program evaluation. Table 17-1 provides a listing of available measures, including information about whether assessments measure skills, tasks, and/or environmental factors.

TABLE 17-1

Instruments for Assessing IADLs and Community Participation for Children and Youth

Data from Bedell, G. M. (2004). Developing a follow-up survey focused on participation of children and youth with acquired brain injuries after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation, 19, 191-205; Bruininks, R. H., Woodcock, R. W., Weatherman, R. F., & Hill, B. K. (1996). Scales of independent behavior—revised (SIB-R). Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing; Dunn, L. (2004). Validation of the CHORES: A measure of children’s participation in household tasks. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11, 179-190; Fisher, A. G. (2003a). Assessment of motor and process skills: Vol. 1. Development, standardization, and administration manual (5th ed.). Fort Collins, CO. Three Star Press; Fisher, A. G. (2003b). Assessment of motor and process skills: Vol. 2. User manual (5th ed.). Fort Collins, CO. Three Star Press; Forsyth, K., Deshpande, S., Kielhofner et al. (2005). The Occupational Circumstances Assessment Interview and Rating Scale (OCAIRS) Version 4.0. Chicago: MOHO Clearinghouse; Giangreco, M., Clonger, C., & Iverson, V. (1997). Choosing options and accommodations for children (COACH) (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Brookes; Glidden, L. M. & Jobe, B. M. (2007). Measuring parental daily rewards and worries in the transition to adulthood. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112(4), 275-278; Keller, J., Kafkes, A; Basu, S., Federico, J., & Kielhofner, G. (2005). Child Occupational Self Assessment (COSA), version 2.1. Chicago, IL: MOHO Clearinghouse; Lambert, N. M., Nihira, K., & Leland, H. (1993). AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scale-School-2. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; Law, M., Baptiste, S., Carswell, A., McColl, M. A., Polatajko, H. & Pollock, N. (2005). The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Ottawa, Canada: CAOT publications ACE; Nollan, K. A., Wolf, M., Ansell, D., Burns, J. Barr, L., Copeland, L., et al. (2000). Ready or not: Assessing youth’s preparedness for independent living. Child Welfare, 79(2), 159-618; Noreau, L., Lepage, C., Boissiere, L., Picard, R., Fougeyrollas, P., Mathieu, J., et al. (2007). Measuring participation in children with disabilities using the Assessment of Life Habits. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 666-671; Sparrow, S., Balla, D., & Cicchetti, D. (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales II. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; Young, N. L., Williams, J. I., Yoshida, K. K., & Wright, J. G. (2000). Measurement properties of the Activities Scale for Kids. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53, 125-137.

Team Evaluations

Team or arena evaluations often arise when youth meet for transitional planning in schools or when children and youth return to school after hospitalization secondary to medical concerns such as traumatic brain or spinal cord injury. Information from multiple perspectives is helpful for a realistic appraisal of the child or youth’s performance in a variety of settings.

Team evaluations also may apply to medical or psychiatric facilities. Medical and rehabilitation facilities may examine IADLs and community participation related to returning home and returning to school. Recently, additional emphasis has been placed on community participation because of research showing concerns in this area for children and youth with acquired or traumatic brain injury and physical disabilities.8,45 Team members often include, but are not limited to, children and youth, caregivers, occupational and physical therapists, speech therapists, nurses, and physiatrists.

Team evaluations may also be part of community system services. Youth in foster care are monitored and evaluated for independent living skills that include IADLs and community participation.46,54 This is also true of many at-risk children and adolescents who are in the juvenile system or are homeless. Many are eligible for independent living programs run through welfare agencies.46 Team members often include, but are not limited to, social workers, foster parents, children and youth in foster care, pediatricians, and occupational therapists. At present, this is an emerging practice area for occupational therapists.4

Measurement of Outcomes

Occupational scientists and therapists along with professionals in rehabilitation and health have developed assessments to measure outcomes of IADLs and community participation (see Table 16-1). With the new International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health for Children and Youth, outcomes may address participation patterns, activity performance, quality of life, client satisfaction, and contextual supports and barriers.85

Assessments for IADLs and community participation are relatively few; most are inventories that are completed by a caregiver. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales II (VABS) is a standardized measure commonly used to measure domestic (IADL) and community skills.73 This measure provides information about the individual and can be used to assess changes over time. The VABS has often been used with children and youth who have intellectual disabilities and with children with ADHD. The Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) is standardized and appears to be sensitive to the progress that children make.22,23 Studies demonstrated that the AMPS can identify differences in IADLs for children with and without ADHD30 and for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy.79

Several new participation assessments have recently become available (see Table 17-1). The Children and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP)8 and the Life Habits Questionnaire (LIFE-H)55 measure participation at home, school, and in the community. These measures produce change scores that can be used to examine outcomes from individual intervention or programmatic outcomes. These measures do not provide information about age ranges but do provide information about the difficulty continuum of the participation items based on Rasch analyses. Measures may be completed by caregiver or teacher and by the child or youth for comparison of perspectives.

The CASP has been used to obtain information about program outcomes for children with TBI.8 The CASP has 20 items that measure participation for children and youth at home, school, and in the community. Some examples of CASP activities are family chores, responsibility, and expectations at home; social activities with friends in the neighborhood or the community; and shopping.8 Parents or caregivers compare their child’s participation to that of typical children of the same age using a 4-point scale ranging from “age expected” to “unable.” This information has been helpful in identifying ongoing intervention concerns after discharge of children with TBI to integrate back into their homes, schools, and communities.

The LIFE-H obtains information about social participation for 5- to 13-year-old children and youth with physical disabilities, TBI, or developmental disabilities.55 Life habits refer to participation in valued everyday activities such as nutrition, fitness, communication, personal care, and valued social roles such as responsibility and community life. Ratings, on a 10-point scale, measure level of participation difficulty, assistance required (compared with that expected for typically developing peers), and satisfaction.

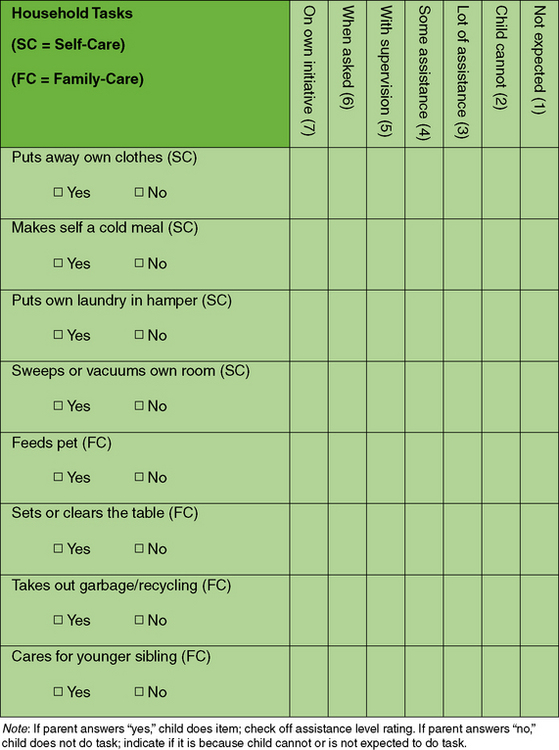

Preparation for independent and interdependent living often is addressed during adolescence; however, research supports monitoring and assessing these performance areas before adolescence. Because children and youth with disabilities often require additional support to learn and perform these mundane tasks, assessment and planning before adolescence are needed. The Children Helping Out: Responsibilities, Expectations, and Supports (CHORES) program was developed for these purposes and provides information about participation in household tasks and some aspects of IADLs.15 In CHORES household tasks include domestic tasks as well as caring for others. Household tasks are organized into two groups: self-care tasks and family-care tasks.84 Self-care refers to household tasks for which the outcomes primarily affect the individual such as picking up one’s clothing or making a cold meal for oneself. Family care refers to household tasks for which the outcomes primarily affect others such as caring for pets and preparing meals (Figure 17-2).

FIGURE 17-2 Examples of CHORES items and ratings for the Children Helping Out: Responsibilities, Expectations, and Supports (CHORES) Program.

Scoring on CHORES provides a way to measure change for individuals across time. Changes are measured by comparing the number of tasks performed and the assistance required to perform household tasks. Two open-ended items provide information about the importance of household task participation to parents and parents’ satisfaction with their children’s household task participation. Refer to Figure 17-2 for examples of items and rating scales for CHORES.

CHORES provides a way to gather information from parents that can contribute to development of interventions that address goals and concerns related to household task performance, as well as to being part of the family. This information can promote discussions about expectations and opportunities and preparation for independent living for children and youth of all abilities.

Information relative to the perspectives and beliefs of children, youth, and caregivers on participation in the community and in IADLs is essential to client-centered and evidence-based practice. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is often used for this purpose.

A new outcome-based measure, the Children’s Occupational Self Assessment (COSA), measures children’s perspectives on their competence and the importance of participation in activities in their homes, schools, and communities.38 Children rate their competence and importance of activities using a four-point pictorial scale of faces and stars. Examples of IADL items are getting chores done and using money to buy things for themselves.

The Transition Daily Rewards and Worries Questionnaire (TDRWQ) provides a way to measure caregivers’ beliefs and concerns for their adolescents who are transitioning to the adult world.29 The TDRWQ is a 28-item measure with four subscales: positive future orientation, community resources, financial independence, and family relations. Parents or caregivers rate items on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Examples are perception of adolescents’ adjustment to living out of the home and perception about schools’ preparation of adolescents for independent living. This measure affords a way to promote discussion and to develop goals and interventions to address preparation of adolescents for independent and interdependent living.

INTERVENTION PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION

Inclusion of the families or caregivers of children with disabilities is essential to promote and reinforce positive self-esteem in everyday life, and to promote self-determination skills for positive social experiences.28,48,76,82,86 Psychosocial skills and community participation–based interventions should be facilitated long before meeting for transition planning.

As children begin their transition to adult roles, the focus of occupational therapy should move toward independent or interdependent living.13 As Orentlicher and Michaels note, the therapist’s goal at this stage is to enable the adolescent to achieve full status as an adult:

Disability is a natural part of human experiences and it does not diminish the right of the individual to live independently, enjoy self-determination, make choices, contribute to society, pursue meaningful careers, and enjoy full inclusion and integration in the economic, political, cultural and educational mainstream of American society (p. 2).56

Transition planning is concerned with the continuing process of moving from a supported home environment to a role of living in the adult community. Adolescents with disabilities or those who are at risk may require more planning, intervention, and support than a typical student.36,37,51,56,57

Occupational therapists often provide services in the school setting to children who experience self-care or functional mobility deficits, rendering a prime opportunity for therapists to implement needed skills for independent living. Because independent living involves participation in activities at home and in the community, expansion of services to home and the community is an area that needs further development. Occupational therapists understand and appreciate the important link between occupations and identity.12,40 Desired outcomes for adolescents with lifelong disabilities include safe, independent or interdependent engagement in occupation in the natural occurring contexts of IADLs in the home or community1 and the formation of a strong, positive disability identity (Case Study 17-1).39

INTERVENTION MODELS AND STRATEGIES

Occupational therapy practitioners and the interdisciplinary team often use a psychosocial approach to enhance the child’s or youth’s sense of control and his/her independence. Empowering an adolescent toward self-determination can facilitate independence.25,76,82,86 One way this can be accomplished during therapy is to include the child/youth in intervention planning and decisions by making choices and problem solving. Collaborative decision making with the youth and family can foster an intentional relationship that leads to increased occupational performance.77 This strategy can be replicated in any area of the child or adolescent’s program. Health care and education professionals are recognizing the need to prepare youth for monitoring and taking care of their daily needs such as medications, making appointments, and assessing accessibility in the community. Increasing independence in all areas of life through adaptations such as work simplification can also help an adolescent feel more competent and able. Decision making and increasing independence are key to feelings of competence and control that can create “strands of coherence” (p. 236)61 as the adolescent becomes an adult.

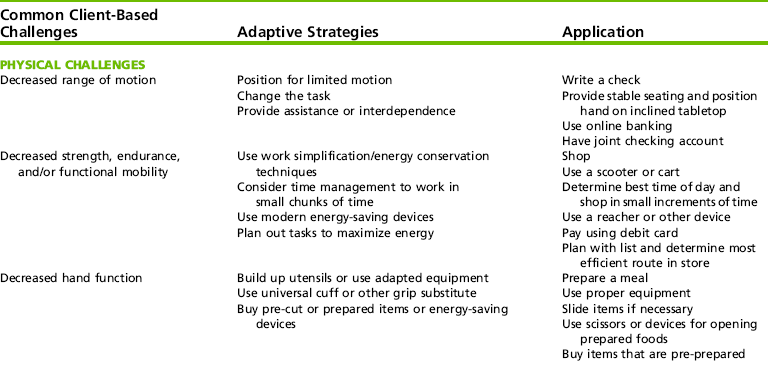

Adaptation/Compensation

An approach frequently used to include people with disabilities in IADLs and community participation is through adaptation/compensation of the environment, task, or person. See Table 17-2 for specific ideas for adaptive success for common physical, cognitive, and psychosocial challenges.

Contextualism

Humphry and Wakeford understand “development of everyday activities as embedded in and inseparable from societal effort to offer occupational opportunities and social processes that are part of participation in everyday activities” (p. 261).34 The contextual approach suggests that occupational therapy practitioners facilitate IADL and community participation by creating accessible contexts for performance. They advocate for the creation of niches or small communities that foster development of roles, patterns, and skills. The use of therapy techniques in the context of real experiences and natural environments is more valuable and essential to the generalization and transfer of these skills. Emphasis on the natural physical and social contexts can enhance children’s development by giving them observation, imitation, and practice opportunities (Case Study 17-2). Approaches that build on natural contexts are described next.

Reverse Inclusion

Instead of including one child with a disability into a program designed for the skill level of typical children, reverse inclusion brings typical children into a program designed for children with special needs. This has been an effective technique to improve age-appropriate behaviors and social skills targeted in the goals and objectives of youth with disability.70 In reverse inclusion, typical peers are brought into occupational therapy groups, special recreation, adapted physical education, and other avenues. Benefits have been documented both for typical peers serving as role models and for youth with disability.70

Supported Inclusion

Young people with disability can be supported in natural environments through the use of assistants, peer partners, and educated classmates. To promote participation supported inclusion usually requires adapted coursework and activities that are consistent with the physical and cognitive abilities of the client.

Family Activities

Occupational therapy practitioners can consult with families regarding ways to include young people with disabilities in family leisure and household activities. This facilitates skills and helps the youth to develop a family role through productive participation in home management and caring for others.15 Use of the landline telephone and cell phone, health management, money management and access skills, safe interaction with strangers, and use of public transportation systems are IADL skills that often are learned in the home. Families may need the assistance of occupational therapy services to recognize the need for the youth to achieve these milestones and to adapt these skills to the level of the youth.

Community Participation

Occupational therapy practitioners should advocate for increased community participation for children and youth through shopping, attending school or community events, recreational activities, and/or other avenues of involvement. They can consult with the family and teachers on strategies to facilitate the child’s use of the telephone, money management, and accessing public transportation. The practitioner can challenge the youth’s physical, cognitive, and social skills through incremental, planned activities in the school and community.

Many IADL and community participation skills are dynamic, complex, and multistep activities, such as cooking, doing laundry, shopping, childcare, and accessing transportation. These tasks are further developed when they are applied in a context that holds meaning for the client. Therefore, finding a task that is meaningful and social and serves a purpose of importance to society will enhance performance. This can be done through cottage industries, whereby the adolescents create and sell merchandise, establish a work-based role, or plan and implement an outing, party, or celebration.

Client-Centered Ecological/Experiential

Emergent literature supports self-determination through development of self-image, independent living skills, problem-solving, and active involvement of youth.76 These researchers advocate for inclusive services that are strength based, widely accessible, and give adolescents opportunities to succeed. Examples of this type of programming are the Community Capacity-Building project, which provided a forum that brought together clients, families, and community stakeholders to increase communication and opportunities,86 and an occupational therapy program that created a “Life Skills Institute” as a comprehensive framework to support youth with disabilities and their families transition into adult services.25

Self-determination can be facilitated through improvement of life skills, social skills, and academics.76 Facilitating positive changes to the client’s physical appearance through use of make-up, jewelry, or fashionable clothing can also promote IADL skills and self-empowerment. Involvement in school-based, recreational, and/or Special Olympics sports or athletics can improve skills, participation, and socialization.47 Enhancing and facilitating positive peer relationships and roles using psychosocial approaches is a necessary part of any IADL intervention plan. Davidson and Fitzgerald advocate for a client-centered approach that includes beginning realistic career exploration early and addressing all areas of adult independence.14

Discounting and empowering are complementary strategies to address empowerment needs in aspects of the client’s life. Discounting, or reframing, is a technique that redefines a disability in terms of what a person can do versus what he cannot do.28,41,50 For example, Evans, McDougall, and Baldwin found that participation of youth with disabilities in many community-based activities without regard to performance fostered development of relationships and social behaviors.18 These workers found that community participation correlated with employment and self-determination. Reframing can be applied to other areas that may be difficult for a child or adolescent to succeed in (e.g., sports and other physical activities). Placing less importance on one area may close the gap between values and perceived competence, a key element to self-esteem and self-identity.

Focus on Ability and Success

For clients who have spent years listening to their areas of deficit, emphasizing their assets and abilities is essential as they become adolescents. Changing the context from one in which the adolescent client always struggles to one in which he or she can succeed is key to this strategy.34 For instance, cooking may be an area in which clients with cerebral palsy or other physical impairment have difficulty. Beginning an IADL session with a safe and physically simple task such as dusting may lead to greater success. The adolescent can be encouraged to compare himself or herself to other adolescents with similar disabilities, instead of with typically developing peers. The Special Olympics camps for children with special needs or support groups are places in which adolescents can experience more success and less competition. Inclusion within the community is positive, but it is also important to establish esteem and disability identity with like peers in adolescence.39

Incorporation of Sexuality and Body Image

Adolescents are developing physically and psychologically, and occupational therapists support these positive moves toward adulthood. Noticing and appreciating the growth, changes, new interests, moves toward independence, and physical attractiveness can help build self-esteem in children and adolescents. Comments about growth and positive changes can be incorporated into personal care, because both male and female clients may have new personal hygiene needs as well as the desire to dress and groom themselves differently. It is important to understand that adolescents with disabilities experience the same hormonal changes as in typical adolescents and perhaps have more questions about what these changes may bring. Families often struggle as their child with a disability becomes a sexual being. The occupational therapist has a key role in addressing this area of occupational performance and these typical aspects of adolescent development.64 One way to accomplish this is to establish clear boundaries for this population, recognized to be vulnerable to sexual abuse.64 The “Circles Program”™ facilitates the establishment of physical boundaries for adolescents with developmental disabilities.75 By teaching safe relationships, appropriate personal space, and sexuality to adolescents with developmental challenges, it is a concrete way of showing clients with intellectual disability how close to let people into their personal space. The concepts of personal space are taught with actual circles around the client: the closest circle indicates the space of closeness with family, the middle circle at forearm length indicates friends, and a wider circle of a full arm’s length is taught for keeping personal space between the youth and acquaintances and strangers.75

Mentoring and Role-Modeling a Positive Future

Many youth with disabilities do not know what their future might hold. Addressing possible avenues for prevocational and vocational programming, as well as independent living, enables these clients to see a hopeful and positive future. Inclusion has caused many children to be separated from role models with similar disabling conditions. Whenever possible, youth with disabilities need exposure to role models of adults with disability working and thriving in the community. Visiting work sites and group homes can help youth with disabilities and their families form a positive future vision.25,86

The use of mentors or positive role models for IADL and community participation skill development is an intervention strategy that can be effectively used to help the youth with disability gain perspective and increase positive self-regard.2 The adolescent client may also serve as a mentor for others by assisting in a younger classroom, tutoring students in simple reading or math subjects, or bringing cookies to elders in the community. An adolescent can be encouraged to mentor a younger child with a similar disability. A mentoring program that pairs a successful adult from the community with an adolescent with a similar disability can also help to increase the adolescent’s confidence.2 Peer and cross-age tutoring in reading or other academic tasks can assist with positive role identity and improve behavior in youth with disability.2

Inclusive Programming for Youth with Disabilities

With the emphasis and importance placed on inclusion, we must seek to have other avenues to provide children and adolescents with experiences with other people with similar abilities. Individualized and person-centered programming such as Special Olympics, specialized summer camp experiences, handicapped ski programs, adaptive sports, support groups, and other avenues should be explored to help the adolescent client develop a disability identity.39,76 Bedell and colleagues emphasize the importance of creating opportunities for learning daily tasks and social skills for school-aged children with brain injuries.7 These authors advocate for involvement of parents in creating opportunities in the community to teach skills for regulation of cognitive and behavioral function within the context of daily life occupations.7

Social Skills Training

Bedell and colleagues suggest that, in the context of daily life, adolescents with acquired brain injuries are more impaired by social behavior and cognitive issues than by movement-related impairment.7 Bedell also stresses the importance of close friends and extracurricular activities as a hallmark of resilient children.6 Support for psychosocial development has been identified as critical to success for adolescents with physical and cognitive/behavioral disabilities.58,76

The main purpose of social skills training is to increase communication and participation in the community. Limitations in the youth’s ability to socially participate (e.g., communication skills, problem solving, recognizing feelings) can be identified, addressed, and improved. Social skills training can be done one on one through practicing case scenarios or in an inclusion setting with the entire class to address peer relationships. These are IADL and community processes and can be included in these milieus.

Support Groups

Groups that consist of like participants—those of a similar age and disability—can be a useful strategy. Creating community connections for support is an important transition component to adulthood for youth with disabilities.86 Creation of networks that include parents, teachers, therapists, and community agencies can facilitate and support the process of transition to adulthood for clients with disability.86 If this cannot be accomplished logistically, virtual support groups and websites can be helpful, so long as the adolescent is monitored while online.

SUMMARY

Occupational therapy practice encompasses the complex process of IADLs and community participation in the lives of children, youth, and their family/support systems. Through the occupational therapy process of assessment, evaluation, intervention, and outcomes analysis, the occupational therapy practitioner uses critical thinking to facilitate IADL skills and community participation into practice. Occupational development is unique to each individual and should be used as a foundation to address the roles, interests, level of independence/interdependence, and quest for meaningful and productive living in clients across settings. As the child/youth develops maturity and skills, the role of parents, professionals, and the youth themselves also evolves. See Table 17-3 for the developmental role continuum.

REFERENCES

1. American Occupational Therapy Association, Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process, 2nd ed. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2008;62:609–639.

2. Anderson, L.B., A special kind of tutor. Professional development and classroom activities for teachers. Teaching prek-8, 2007;37(5). Retrieved June 13, 2008, from, http://www.teachingk-8.com.

3. Andrén, E., Grimby, G. Activity limitations in personal, domestic and vocational tasks: A study of adults with inborn and early acquired mobility disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2004;26:262–271.

4. Aviles, A., Helfrich, C. Life skill service needs: Perspectives of homeless youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:331–338.

5. Barnhart, R.C. Aging adult children with developmental disabilities and their families: Challenges for occupational therapists and physical therapists. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2001;21(4):69–81.

6. Bedell, G.M. Developing a follow-up survey focused on participation of children and youth with acquired brain injuries after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19:191–205.

7. Bedell, G.M., Cohn, E.S., Dumas, H.M. Exploring parents’ use of strategies to promote social participation of school-aged children with acquired brain injury. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005;59:273–284.

8. Bedell, G.M., Dumas, H.M. Social participation of children and youth with acquired brain injuries discharged from inpatient rehabilitation: A follow-up study. Brain Injury. 2004;18:65–82.

9. Blackorby, J., Wagner, M. Longitudinal postschool outcomes of youth with disabilities: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth. Exceptional Children. 1996;62:399–413.

10. Bowes, J.M., Flanagan, C., Taylor, A.J. Adolescents’ ideas about individual and social responsibility in relation to children’s household work: Some international comparisons. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:60–68.

11. Chandler, B.E., Schoonover, J., Clark, G.F., Jackson, L.L. The magnificent mundane. School System Special Interest Section Quarterly. 2008;15(1):1–4.

12. Christiansen, C.H. Defining lives: Occupation as identity: An essay on competence, coherence and creation of meaning. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1999;53:547–558.

13. Conaboy, K.S., Davis, N.M., Myers, C., Nochajski, S., Sage, J., Schefkind, S., et al. FAQ: Occupational therapy’s role in transition services and planning. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008.

14. Davidson, D.A., Fitzgerald, L. Transition planning for students. OT Practice. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, 2001.

15. Dunn, L. Validation of the CHORES: A measure of children’s participation in household tasks. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;11:179–190.

16. Dunn, L., Coster, W.J., Orsmond, G.I., Cohn, E.S. Household task participation of children with and without attentional problems in household tasks. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2009;29:258–273.

17. Dunst, C.J., Bruder, M.B., Trivette, C.M., Hamby, D.W. Young children’s natural learning environments contrasting approaches to early childhood intervention indicate differential learning opportunities. Psychological Reports. 2005;96:231–234.

18. Evans, J., McDougall, J., Baldwin, P. An evaluation of the “Youth En Route” program. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2006;26(4):63–87.

19. Feeney, T., Ylvisaker, M. Context-sensitive cognitive-behavioural supports for young children with TBI: a replication study. Brain Injury. 2006;20:629–645.

20. Field, S., Martin, J., Miller, R., Ward, M., Wehmeyer, M.L. A practical guide for teaching self-determination. Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children, 1998.

21. Fiese, B.H., Tomcho, T.J., Douglas, M., Josephs, K., Poltrock, S., Baker, T. A review of 50 years of naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:381–390.

22. Fisher, A.G. Assessment of motor and process skills: Vol. 1. Development, standardization, and administration manual, 5th ed. Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press, 2003.

23. Fisher, A.G. Assessment of motor and process skills: Vol. 2. User manual, 5th ed. Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press, 2003.

24. Forness, S.R., Serna, L.A., Nielsen, E., Lambros, K., Hale, M.J., Kavale, K.A. A model for early detection and primary prevention of emotional or behavioral disorders. Education & Treatment of Children. 2000;23(3):325–345.

25. Gall, C., Kingsnorth, S., Healy, H. Growing up ready: A shared management approach. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2006;26(4):47–62.

26. Gallimore, R., Goldenberg, C.N., Weisner, T. The social construction and subjective reality of activity settings: Implications for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:537–559.

27. Giangreco, M., Clonger, C., Iverson, V. Choosing options and accommodations for children (COACH), 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes, 1997.

28. Gill, C.J., Kewman, D.G., Brannon, R.W. Transforming psychological practice and society: Policies that reflect the new paradigm. American Psychologist. 2003;58:305–332.

29. Glidden, L.M., Jobe, B.M. Measuring parental daily rewards and worries in the transition to adulthood. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112:275–278.

30. Gol, D., Jarus, T. Effect of a social skills training group on everyday activities for children with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2005;47:539–545.

31. Goodnow, J.J., Delaney, S. Children’s household work. Task differences, styles of assignment, and links to family relationships. Journal of Applied Development Psychology. 1989;10:209–226.

32. Healy, H., Rigby, P. Promoting independence for teens and young adults with physical disabilities. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1999;66:240–249.

33. Hillier, A., Fish, T., Cloppert, P., Beversdorf, D.Q. Outcomes of a social and vocational skills support group for adolescents and young adults on the autism spectrum. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2007;22:107–115.

34. Humphry, R., Wakeford, L. An occupation-centered discussion of development and implications for practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;60:258–267.

35. Jinnah, H.A., Stoneman, Z. Parents’ experiences in seeking child care for school age children with disabilities—where does the system break down? Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:967–977.

36. Johnson, D.R., Challenges of secondary education and transition services for youth with disabilities. Impact: The Institute of Community Integration 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2007, from, http://iciumnedu/products/impact/163/overs.html.

37. Johnson, D.R., Stodden, R.A., Emanuel, E.J., Luecking, R., Mack, M. Current challenges facing secondary education and transition services: What research tells us. Exceptional Children. 2002;68:519–531.

38. Keller, J., Kafkes, A., Basu, S., Federico, J., Kielhofner, G. Child Occupational Self Assessment (COSA), version 2.1. Chicago: MOHO Clearinghouse, 2005.

39. Kielhofner, G. Rethinking disability and what to do about it: Disability studies and its implications for occupational therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005;59:487–496.

40. Kielhofner, G. Model of human occupation: Theory and application, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

41. Kinavey, C. Explanatory models of self-understanding in adolescents born with spina bifida. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:1091–1107.

42. King, G., Law, M., Hanna, S., King, S., Hurley, P., Rosenbaum, P., et al. Predictors of the leisure and recreation participation of children with physical disabilities: A structural equation modeling analysis. Children’s Health Care. 2006;35(3):209–234.

43. King, G., Law, M., King, S., Rosenbaum, P., Kertoy, M., Young, N. A conceptual model of the factors affecting the recreation and leisure participation of children with disabilities. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2003;23(1):63–90.

44. Kingsnorth, S., Healy, H., Macarthur, C. Preparing for adulthood: A systematic review of life skill programs for youth with physical disabilities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:323–332.

45. Law, M., Petrenchik, T., King, G., Hurley, P. Perceived environmental barriers to recreational, community, and school participation for children and youth with physical disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2007;88:1636–1642.

46. Lemon, K., Hines, A.M., Merdinger, J. From foster care to young adulthood: The role of independent transition programs in supporting successful transitions. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:251–270.

47. Loukas, K.M., Cote, T. Sports as occupation. OT Practice. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, 2005.

48. Magill, J., Hurlbut, N.L. The self-esteem of adolescents with cerebral palsy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1986;40:402–407.

49. Massinga, R., Pecora, P.J. Providing better opportunities for older children in the welfare system. [Electronic version]. Future of Children. 2004;14(1):150–173.

50. Mayberry, W. Self-esteem in children: Considerations for measurement and intervention. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1990;44:729–734.

51. Michaels, C.A., Orentlicher, M.L. The role of occupational therapy in providing person centered transition services: Implications for school based practice. Occupational Therapy International. 2004;11(4):209–228.

52. Mihaylov, S.I., Jarvis, S.N., Colver, A.F., Beresford, B. Identification and description of factors that influence participation of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2004;46:299–304.

53. Moore, K.A., Chalk, R., Scarpa, J., Vandievere, S. Family strengths: Often overlooked, but real. Child Trends Research Brief. 2002:1–8.

54. Nollan, K.A., Wolf, M., Ansell, D., Burns, J., Barr, L., Copeland, L., et al. Ready or not: Assessing youth’s preparedness for independent living. Child Welfare. 2000;79(2):159–176.

55. Noreau, L., Lepage, C., Boissiere, L., Picard, R., Fougeyrollas, P., Mathieu, J., et al. Measuring participation in children with disabilities using the Assessment of Life Habits. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007;49:666–671.

56. Orentlicher, M.L., Michaels, C.A. Some thoughts of the role of occupational therapy in the transition from school to adult life: Part I. Developmental Disabilities Special Interest Section Quarterly. 2000;7(2):1–4.

57. Orentlicher, M.L., Michaels, C.A. Some thoughts of the role of occupational therapy in the transition from school to adult life: Part II. Developmental Disabilities Special Interest Section Quarterly. 2000;7(3):1–4.

58. Orsmond, G.I., Krauss, M.M., Seltzer, K.K. Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:245–256.

59. Palmer, S., Wehmeyer, M. Promoting self-determination in early elementary school. Remedial and Special Education. 2003;24:115–126.

60. Parish, S.L., Cloud, J.M. Child care for low-income school-age children: Disability and family structure effects in a national sample. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:927–940.

61. Peloquin, S.M. Occupations: Strands of coherence in a life. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;60:236–239.

62. Polatajko, H.J., Mandich, A. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance with children with developmental coordination disorder. In: Katz N., ed. Cognition and occupation across the life span. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association Press; 2005:237–260.

63. Poulsen, A.A., Rodger, S., Ziviani, J.M. Understanding children’s motivation from a self-determination perspective: Implications for practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2006;53(2):78–86.

64. Preston, L., Lewin, J.E., Understanding issues of sexuality and privacy for individuals with developmental disabilities. OT Practice, Bethesda, MD, American Occupational Therapy Association, 2006;11:CE1–CE8. [22].

65. Richardson, P. From roots to wings: Social participation for children with physical disabilities. Developmental Disabilities Special Interest Section Quarterly. 2003;26(1):1–4.

66. Rodger, S. I can do it: Developing, promoting, and managing children’s self-care needs. In: Rodger S., Ziviani J., eds. Occupational therapy with children. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2006:200–221.

67. Rodger, S., Ireland, S., Vun, M. Can Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) help children with Asperger’s syndrome to master social and organizational goals? British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;71(1):23–32.

68. Rogoff, B. The cultural nature of human development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003.

69. Savage, S.L., Gauvain, M. Parental beliefs and children’s everyday planning in European-American and Latino families. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1998;19:319–340.

70. Schoger, K.D., Reverse inclusion: Providing peer social interactions opportunities to students placed in self-contained special education classrooms. TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus, 2006;2(6). Article 3. Retrieved September 8, 20008 from, http://escholarship.bc.edu/education/tecplus/vol2/iss6/art3.

71. Shogren, K.A., Turnbull, A.P. Promoting self-determination in young children with disabilities: The critical role of families. Infants & Young Children. 2006;19:338–352.

72. Simons, D. Adolescent development. In: Cronin A., Mandich M.B., eds. Human development & performance. Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learing; 2005:216–246.

73. Sparrow, S., Balla, D., Cicchetti, D. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales II. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services, 2005.

74. Spence, S.H. Social skills training with children and young people: Theory, evidence and practice. Child & Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;8:84–96.

75. Stanfield, J. James Stanfield catalogue: Special education, school to life transitions, conflict resolution and violence prevention. Santa Barbara, CA: James Stanfield, 2007.

76. Stewart, D., Stavness, C., King, G., Antle, B., Law, M. A critical appraisal of literature reviews about the transition to adulthood for youth with disabilities. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2006;26(4):5–24.

77. Taylor, R.R. The intentional relationship: Occupational therapy and use of self. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 2008.

78. Turnbull, Turnbull. Self-determination for individuals with significant cognitive disabilities and their families. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 2001;26:56–62.

79. Van Zelst, B., Miller, M., Russo, R., Murchland, S., Crotty, M. Activities of daily living in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: a cross-sectional evaluation using the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2006;48:723–727.

80. Wagner, M., Cameto, R., Newman, L. Youth with disabilities: A changing population. A report of findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study (NLTS) and the National Longitudinal Transitions Study-2 (NLTS2). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International, 2003.

81. Wehmeyer, M.L., Sands, D.J., Doll, B. The development of self-determination and implications for educational interventions with students with disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education. 1997;44:305–328.

82. Wehmeyer, M.L., Palmer, S.B. Adult outcomes for students with cognitive disabilities three years after high school: The impact of self-determination. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2003;38:131–144.

83. Wehmeyer, M.L., Schwartz, M. Self-determination and positive adult outcomes: A follow-up study of youth with mental retardation or learning disabilities. Exceptional Children. 1997;63:245–255.

84. White, L.K., Brinkerhoff, D.B. Children’s work in the family: Its significance and meaning. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1981;43:789–798.

85. World Health Organization. International classification of functioning: Child and Youth Version (ICF-CY). Geneva: Author, 2007.

86. Wynn, K., Stewart, D., Law, M., Burke-Gaffney, J., Moning, T. Creating connections: A community capacity-building project with parent and youth with disabilities in transition to adulthood. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2006;26(4):89–103.

87. Zhang, D. Parent practices in facilitating self-determination skills: The influences of culture, socioeconomic status, and children’s special education status. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2005;30(3):154–162.

1We acknowledge the original work of Jayne Shepherd, MS, OTR/L, as a framework for this chapter. We thank Bevin Journey, MSOT, OTR/L, for background research that laid the groundwork for the intervention section of this chapter, as well as the University of New England graduate student research team of Tracy Floyd, Betsy Davis, Amanda Milose, and Erin Shugrue. We also gratefully acknowledge the editorial input of Helene Lohman, OTD, OTR/L and Nancy Davis, OTD, OTR/L of the Creighton University Post-Professional Doctoral program.

CASE STUDY 17-1

CASE STUDY 17-1