Activities of Daily Living

1 Describe the effects of context on a child’s performance and parental expectations for activities of daily living (ADLs).

2 Identify the body structures and functions, performance skills, performance patterns, and activity demands that may affect a child’s ADL performance.

3 Identify evaluation procedures and methods in ADLs that target child and family preferences for intervention.

4 Describe intervention strategies and approaches, both general and specific.

5 Describe the selection and modification of equipment, techniques, and environments for certain ADL occupations.

Activities of daily living (ADLs) encompass some of the most important occupations children learn as they mature. Self-care or ADLs include learning how to take care of one’s body, such as toilet hygiene, bowel and bladder management, bathing and showering, personal hygiene and grooming, eating and feeding, dressing, and functional mobility.1 Other ADLs tasks include caring for a personal device and learning to express sexual needs.1 As the child matures, he or she learns to perform ADLs in socially appropriate ways so that he or she can engage in the other occupations within the family unit and the community such as education, play, leisure, rest and sleep, social participation, instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and work. Often when a child is young, he or she performs ADLs as co-occupations of caregivers and children, especially when the child has a disability. Parents often establish the routines for bathing, dressing, feeding, and delegate more complex ADLs to others.1,80,127,149

This chapter discusses the dynamic interaction of child factors, contexts, activity demands, and performance skills and patterns that allows a child to engage in ADL occupations in a variety of environments. Evaluation methods, intervention approaches, and strategies for improving outcomes in ADL activities are reviewed. Typical development, limitations, and modifications for toileting, dressing, bathing, grooming, and performing other related ADL tasks are described (feeding is discussed in Chapter 15). Examples of adaptations to physical and social environments are provided, with consideration given to cultural, temporal, virtual, and personal influences.

IMPORTANCE OF DEVELOPING ADL OCCUPATIONS

The foundations for mastering ADLs begin in infancy and are refined throughout the various stages of development. As unique individuals living in certain contexts, children learn these activities at varying rates and have occasional regression and unpredictable behaviors. Cultural values, parental expectations, social routines, and the physical environment influence when children begin to bathe, dress, groom, or toilet themselves. Overall, society and families assume that children develop increasing levels of competence and self-reliance to meet their own ADL needs. Growth and maturity allow the child to participate in various roles and environments with decreasing levels of adult supervision for ADLs.

When a child is born with or acquires a disability, parental and child expectations for ADL and daily living independence are modified. Occupational therapists are instrumental in helping parents and children learn how to modify activity demands and routines so that children perform ADL tasks within their everyday environments. Active participation in ADLs has several benefits for the child, including maintaining and improving bodily functions and health (e.g., strength, endurance, range of motion [ROM], coordination, memory, sequencing, concept formation, body image, cleanliness in hygiene) and problem solving while mastering tasks that are meaningful and purposeful to the child. This task mastery leads to increased self-esteem, self-reliance, and self-determination and gives the child a sense of autonomy. When children dress themselves, they may choose their own clothing, participate in dress-up during playtime, put on a coat when going outside, change clothes for gym class, or dress in a uniform to work at a restaurant. As the child learns new ADL tasks, he or she develops a sense of accomplishment and pride in his or her abilities. This increasing independence also gives parents, teachers, and other caregivers more time and energy for other tasks53 while the child contributes to the family unit.

As a child learns new ADL tasks, routines or patterns of observable behaviors develop. These repetitive routines (e.g., morning routine for getting ready for school, bedtime routines) are embedded within the family culture and environment.40,128 Therapists ask parents about daily routines and customs at home or school that may influence a child’s ADL performance. Some examples of questions to consider asking are “When are children expected to be toilet trained or independent in brushing their teeth? How is your child expected to get from room to room in your house or within school? Can you please describe your morning routine?”

Routines help satisfy or promote the completion of ADL tasks to meet role expectations within home, school, community, and work environments. They are culturally based and often are a combination of what is expected but also what is practical.50 Each family, teacher, employer, or community organization may follow a unique routine for self-care tasks. For example, the family may require a toilet break anytime they are going somewhere, and teachers may allow students to use the toilet at fixed times during the day. Sometimes routines become damaging and hinder performance of ADL.1,40,128 For example, a child with autism or obsessive-compulsive disorder may be quite rigid about how he performs his grooming tasks and is inflexible when Aunt Lou visits and the placement of items in the bathroom changes.149 He also may routinely wash his hands after he touches any object. These patterns of behavior now interfere, instead of support, ADL performance. Families may have routines or no routines that affect ADL performance (e.g., when they eat, when bathing occurs, how often laundry is done, or how children are expected to manage personal items such as glasses, retainers). As a child matures, he becomes more responsible for developing and maintaining routines that become habits to prevent further illness and maintain health and well-being. Checking skin conditions, maintaining cleanliness during toileting or bathing, preventing cavities through tooth brushing, and maintaining personal care devices such as orthotics or catheters are a few of the healthy living routines that help the child meet role expectations for community living.

FACTORS AFFECTING PERFORMANCE

Child factors, the performance environment, contextual aspects, and the specific demands of the self-care activity, as well as the child’s performance skills, affect the child’s ability to participate successfully in ADL occupations. ADLs are performed in a context of interwoven internal and external conditions, some from within the child (bodily functions and body structures related to the disability; personal and cultural contexts) and others around the child (social and physical environments; virtual, cultural, and temporal contexts).1 During ADL occupations, the context influences the activity demands, which vary in object use, space and social demands, sequencing and timing, required actions, bodily functions, and the body structures involved. As therapists consider these factors, they determine the knowledge and performance skills (goal-directed actions) and patterns the child needs to learn self-care.

Child Factors and Performance Skills

Occupational therapy intervention to increase ADL function considers what the child and family value and the context in which tasks occur. The levels of independence, safety, and adequacy of occupational performance of the child and family determine the child’s ADL occupations in various contexts.

Specific child factors (body structures and functions), performance skills, and performance patterns will affect ADL performance. For example, children with tactile hypersensitivity may cry during dressing and refuse to dress despite having the motor and cognitive skills to do so. Children with visual impairments may need to use their sense of touch when brushing their hair.102 A child with cerebral palsy may not have the postural control to sit up during dressing but may have the sensory perceptual skills (e.g., right-left discrimination and figure-ground) to dress in a side-lying position. A child with attention-deficit disorder may have all the motor and sensory perceptual skills to complete a self-care task, but his or her cognitive organization, sequencing, and memory may interfere with adequate, safe performance.139

Interest level, self-confidence, and motivation are strong forces that help children attain levels of performance that are either above or below expectations. Children with intellectual disabilities, traumatic brain injury, or multiple disabilities have trouble in coordination, initiative, attention span, sequencing, memory, safety, and ability to learn and generalize activities across environments. However, with instruction and opportunity, ADLs sometimes become the tasks these children perform most competently.79,111

The child’s disability or health status may affect his or her ability to perform ADL tasks and may also affect caregiver–child interaction during ADL tasks. The child’s capacity for learning and ability to complete difficult tasks safely are considered. Pain, fatigue, the amount of time the child needs to complete the task, and the child’s satisfaction with his or her performance influence the choice of ADL occupations.69 In a study by Kadlec, Coster, Tickle-Degnen, and Beeghly,76 caregiver–child responsiveness was videotaped for three groups of 30-month-old children and their caregivers. Groups included children born full term, children born at a very low birth weight with no white matter disorders, and children born at very low birth weight with white matter disorders. During feeding and dressing activities, mothers of the very-low-birth-weight children tended to adjust to their child’s motor and cognitive needs by giving more directive and positive emotional and social assistance during ADLs than parents of children who were born full term. Similarly, in both high- and low-risk groups of children, Landry, Miller-Loncar, and Smith found high responsiveness of caregivers when involved in daily activities.91 Information from these studies may help therapists consider how caregivers actively support ADL participation by modifying the social and physical environment or by changing the demands of the ADLs.76,79 The first-hand knowledge of parents and caregivers about strategies that “work” with their child and within their family routines is essential to consider in planning ADL intervention.5,50,128,129

Children who are acutely ill or who have multiple disabilities that require numerous procedures throughout the day (e.g., tube feeding, tracheotomy care, bowel and bladder care) may not have the time or energy to work on ADL tasks. For example, Jenna, a 10-year-old child with a C6 spinal cord injury and quadriplegia, can dress herself independently within a 45-minute period, but she and her family prefer that someone else dress her so that she has more energy for school tasks. Children with multiple disabilities may physically be unable to do all or any part of ADL tasks, but they can partially participate or direct others on how to care for them (Case Study 16-1). When children are hospitalized for long periods, they often need to have some control over their participation in self-care routines. Figure 16-1 shows how doing a small part of self-care routines is possible and meaningful for children in the hospital with acute illnesses.

Performance Environments and Contexts

The initiation and completion of ADL tasks are influenced by the context of the tasks, including interwoven conditions both internal and external to the child (e.g., personal, cultural, temporal, and virtual contexts) and around the child (physical and social environments). Children in early and middle childhood often perform ADLs in different settings. The four primary settings that children experience are home, school, community, and work. Once the occupational therapist understands the contexts in which occupation occurs, intervention strategies congruent with the demands of the activity are chosen or aspects of the environment that are barriers to the child’s performance of ADL tasks are modified. Although this section has divided the contexts into various areas, all of the areas are interrelated.

Personal and Temporal Contexts: Family Life Cycle and Developmental Stage

Age, gender, education, and socioeconomic status define the personal context for ADL occupations.1 In assessing dressing, awareness of the personal context is critical in choosing age- and gender-appropriate clothing that is within the family’s budget. The time of day or year; the life stage of the child or other family members; and the duration, sequence, or past history of the activity are included in the temporal context.1 Consider Cory, who is learning to tie his shoes. A routine method is established so he does the task the same way every time he tries it (e.g., first pull both laces tight, then make an X). Cory practices it every time he tries to tie his shoes but becomes frustrated easily. If mom and dad work, practicing shoe tying before going to school can work if they all get up 15 minutes earlier in the morning and Cory doesn’t become frustrated with the time constraints. When the season changes, Cory must not only tie his shoes, but also don boots and extra clothes (e.g., mittens and snow pants). With these additional time constraints, his parents may decide to practice shoe tying at a different time of the day.

Children typically master ADLs in a sequence, achieving specific tasks as overall competency increases. The sequence of ADL development helps therapists and families form realistic expectations for children at different ages and helps determine the appropriate timing for teaching these occupations. By considering the child’s age, therapists determine when it is time to stop working on specific preparatory or therapeutic activities. For example, 6-year-old Tilly has received occupational therapy for 5 years to enhance eating by trying to increase lip closure and to develop a more efficient suck-swallow pattern. If she has not learned this over the past 5 years, what are her chances of learning it this year? It may be time for the therapist to work on self-feeding strategies or on an IADL activity, such as operating an appliance with a switch for meal preparation.

Families vary in their ability and availability to assist and encourage the child to perform ADLs. This ability often depends on where the family and child are in the family life cycle, the personal factors or characteristics of the child, and the family’s ability to spend time and be flexible in everyday routines.5,146,149 When their child is an infant, parents often seek instruction on feeding, dressing, and bathing. By 3 years of age, the child’s self-feeding, dressing, and toileting skills may become issues for parents if the child has a disability. For example, if Mary is the last of seven children, increased ADL independence in feeding or dressing may be less important because her older siblings love to feed and dress Mary. As Mary transitions into a daycare setting or another sibling is born, learning basic ADL skills may become a priority.

When the child enters elementary school, typically by 6 years of age, functional mobility in the school environment, dressing (especially outerwear), toileting, socialization with peers, grooming (e.g., washing the hands and face), and functional communication (e.g., writing, drawing, and expressing needs) become increasingly important. As older siblings become more aware of and sensitive to the child’s disability, they may ignore their brother or sister in community settings or be more motivated by the therapist to help the child learn ADL tasks.

During adolescence (13 to 21 years), parents and child can begin to have different concerns and goals for therapy. Both may be concerned about the adolescent’s independence in ADL; however, adolescents may have more concerns about fitting in with a social group.101 When children who require maximum physical assistance in ADLs approach adulthood, they may become a great concern to parents. For the first time, parents may not have the physical strength to handle the daily care needs of their child or may voice concerns about the child’s safety if someone else provides the caretaking.

Increasing independence in ADL tasks during adolescence often determines whether a child will fit in with peers, obtain a job, or go to college outside the school and family environment. The child takes on increased responsibility for managing ADL routines, caring for personal devices, and perfecting grooming skills (e.g., shaving, hair styling, skin care, braces). During this stage, families further investigate current community resources as they think about future living arrangements, vocational opportunities, and the availability of other recreational activities for their child.146 Additional IADL tasks are introduced to promote independence during this stage, including caring for clothing, preparing meals, shopping, managing money, and maintaining a household.65 Parent issues may focus on the child’s ability to express sexual needs, to be safe in many environments, and to respond appropriately to emergencies.

Social Environment

The social environment, family, other caregivers, and peers provide encouragement and support ADL independence. They also shape expectations regarding the child’s ADL occupations. In large families, different members may be assigned to perform or to help with specific ADL tasks for a child with a disability; in other families, the parent may be the sole person responsible for the daily living needs of the child. Family expectations, roles, and routines for managing daily living needs also influence the child’s development of ADL and performance patterns.146 For example, parents living on a farm may expect their child to get up at dawn, put on overalls and boots, do chores such as feeding the animals, receive home schooling, and help sell eggs to augment the family income.

When planning treatment, the therapist considers personal characteristics of family members, such as temperament, coping abilities, flexibility, and health status (see Chapter 5).146 For example, the mother may place her older child in the “mothering” role if she is depressed and unable to get out of bed and begin the morning routine. Parents with intellectual disabilities or mental health problems may need to see a therapist modeling a behavior to learn how to cue and structure a task for their children.38,146 Parents with physical problems may need instructions and practice in using specific techniques and assistive devices safely.

An analysis of social routines helps determine when and how ADLs are taught. Routines may differ significantly across home, school, community, and recreational environments. The variation in routine may confuse or disorganize children with intellectual disabilities, autism, or attention-deficit disorders, but may be motivating to children without attention, sensory, or cognitive problems. School-based and early intervention therapists need to be aware of the social routines so that they can choose appropriate times to teach tasks. When tasks are taught or practiced at times and places where they occur naturally, they more quickly become part of the child’s behavior repertoire.15 For example, school-based therapists may meet children at the bus to work on functional mobility and may be present as the child removes his or her coat to work on dressing. When tasks are embedded throughout all environments, children have multiple opportunities to practice activities and learn how to use the natural cues in the environment to modify their behavior. Social interactions and networks of peer buddies are extremely powerful in motivating children71 and helping them succeed in self-care. Judie Schoonover, an occupational therapist and assistive technology specialist in Virginia, describes creative routines to practice ADL tasks within the school routine:

Rehearsing routines such as dressing and undressing for toileting with students with limited cognition is not meaningful when practiced separate from their daily routines. They do not understand why they are undressing, then pulling their pants right up without using the toilet! Instead, I have asked their mothers to send snacks to school in something that snaps, unbuttons, or zips. Guess what? Undoing fasteners to get a snack out is far more engaging, and doesn’t require weekly OT sessions in the therapy room.

Another strategy I’ve used for a child working on an IEP goal of shoe tying or buttoning (but who doesn’t wear buttons or tie shoes!) is to talk with her teacher about incorporating tying a bow as part of her behavior plan. Whenever the child accomplishes a task in class, she buttons a button on an incentive chart or ties a bow on a special dowel rather than put[ting] a sticker on a chart (p. 10).62

Cultural Context

As therapists work with children and families in an array of service provision models, they must be aware of their own and others’ cultural beliefs, customs, activity patterns, and expectations for performance in ADLs.97 An occupational therapist may become involved with a family because someone else believes that services are needed, and the family may not welcome the therapist’s personal questions about the child’s and family’s self-maintenance occupations and routines. Cultural expectations of the family, caregivers, and social group as a whole may determine behavior standards. Family beliefs, values, and attitudes about childrearing, autonomy, and self-reliance influence how parents perceive ADLs. In Anglo-European cultures, parents usually are concerned about children meeting developmental milestones,64 while other cultures (e.g., Hispanic) may be more relaxed about milestone attainment.155 Children may not be taught to button their coat, tie shoes, or cut food until a later age because parents may value this role as part of their caregiving and affection for the child.22

Social role expectations and routines are influenced by culture. In a study by Horn, Brenner, Rao, and Cheng, African American parents expected toilet training routines to begin at an earlier age (18 months) than did Caucasian parents of a higher income level (25 months).70 Many Anglo-European parents encourage children to become independent and self-reliant.64 In contrast, many Hispanic families155 and Asian families22 may encourage dependency or interdependency in the family. Routines for dressing, feeding, bathing, going to bed, and carrying out household tasks vary among cultural groups. For example, bathing may occur less than once a day in some cultures, and hairstyles and head garments may be worn for different occasions depending on the child’s cultural group.

Culture also influences the type and availability of tools, equipment, and materials a child uses to perform ADLs. Customs and beliefs may determine how parents dress their children, what they feed them, what utensils are used for self-feeding, how they prepare food, what type of adaptations are acceptable to them, and how they meet health care needs. For example, by custom, Muslim or non-Muslim families from the Middle East may eat only with the right hand because their left is used for toileting.96 Economic conditions, geographic location, and opportunities for education and employment can help determine the types of resources and supports that are available to families. Economics influence ADL tasks in many ways: shoes may be old and the wrong size, indoor plumbing may be nonexistent, or nannies may be expected to dress, groom, or feed a young child with disabilities.

Physical Environment

Barriers in the physical environment, including terrain and furniture and other objects, may hinder the child’s ability to improve performance of ADLs. Inaccessible buildings and rooms crowded with furniture limit how children in wheelchairs move throughout the environment. On the other hand, a large, open space may be too much room to allow a preschooler to contain his or her excitement and complete ADL tasks. Differences in surfaces also affect mobility; for example, rugs can make using a walker or wheelchair more difficult. Other physical characteristics that the therapist assesses relate to the type of furniture, objects, or assistive devices in the environment and whether they are usable and accessible. What is usable in one environment (e.g., a particular type of toilet at home) may not be usable in other environments, such as a hospital or job site. Sensory aspects of the physical environment often influence performance (e.g., the type of lighting, noise level, temperature, visual stimulation, and tactile or vestibular input of tasks). In particular, children with autism or attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are often overly sensitive to and distracted by the sensory aspects of an environment.

The objects used to perform ADL tasks may help or hinder ADL performance. Clothing items (e.g., clothes with snaps, hook-and-loop shoes), grooming items (e.g., toothbrushes or toothpaste dispensers of various sizes and designs), or bathing items (e.g., type of soap, bathing mitt, feel of towel) may either motivate or distract the child. ADL objects or assistive devices need to be accepted and “fit” the child and family’s preferences and meet the demands of the social, cultural, and physical environment.

Virtual Context

In today’s world, the virtual context is considered for ADL evaluation and intervention. Options for teaching ADLs include videos, computers, televisions, personal digital assistants (PDA), or digital memo devices. “Talking books”, visual schedules and stories using digital pictures, computer-generated checklists, or CDs may be used as cues to improve dressing, toileting, hand washing, and other ADL skills.78,133 Recent research has demonstrated the effectiveness of using videos of others (video modeling [VSM]) or videos of the child himself performing a task (video self-modeling).8,99 These videos may be played on an MP3 player, a PDA, or a computer and uploaded to a website for use at other times.

Older children and adolescents may use the Internet to learn more about fashion and style and to communicate with friends and others with similar disabilities or interests through email, blogs, or forums. Numerous checklists, assessments, and schedulers, and a wealth of information about ADLs can be found online. Parents, teachers, children, and therapists collaborate in the use of these resources to enhance performance. The Evolve website lists Internet resources for ADLs.

Assistive technology may help children with disabilities access the Internet, communicate, or set up reminders to perform ADL occupations (see Chapter 20). Mentors and support groups for individuals learning how to care for their own needs and live in the community are also available. An exceptional website is Blackboards and Band-Aids (http://www.faculty.fairfield.edu/fleitas), which was developed by a nurse to offer a forum for children and adolescents with chronic health care needs to discuss their day-to-day issues. Here children talk about themselves, allowing other professionals, families, siblings, and friends to understand their dilemmas and celebrations while living with a health care problem. Children post reflections about their disease and how they participate in different social situations. They also post poetry, art, and other information.

Activity Demands

The activity demands in certain contexts facilitate or impede the quality of ADL performance. A task analysis helps the therapist understand the complexity and various aspects of the activity. This evaluation involves analyzing the objects used, space and social demands, sequencing and timing, and required actions and skills.1 Activity demands vary in the clinic, home, school, and community. For example, when an adolescent with a traumatic brain injury is learning to style her hair, the adolescent’s performance skills may vary significantly in the occupational therapy clinic from those observed in her hospital or home bathroom. The child’s unfamiliarity with the setup of the sink or bathroom may disrupt the flow of motor skills, and the spatial arrangements, lighting, and surface availability may cause process skill problems. For the activity, specific steps are followed and sequenced according to time requirements. (Verbal instruction in sequencing will support performance of ADL tasks—for example, “first you comb the knots out of your hair, then you part the hair and comb it. After a minute of brushing the hair, use the curling iron”). If the adolescent is doing this with friends, the demand on performance skills increases as the number of tasks or steps and the social demand to share supplies and to converse increase. In summary, grading ADL performance involves considering adaptations to the environment, the type of activity or interactions required, and the sequence of the activity. Occupations are viewed according to the environments in which they occur, the demands of the activity, and the child’s abilities.

EVALUATION OF ADLS

Families and their children play key roles in determining which evaluation procedures are used. By working collaboratively with families, therapists learn about the child, the various environments in which ADLs occur, the demands of the activities, and the expectations and concerns of the family. When children get older and are able to communicate, the therapist includes them in determining what areas of ADLs are important to them. The parents and the child often become more vested in the results if the therapist gives them a chance to select or refuse evaluations and to choose where and when the evaluation is completed.54 This approach also gives therapists a better understanding of the contexts in which the child performs occupations and of current performance patterns that may be valued by the family.

Evaluation Methods

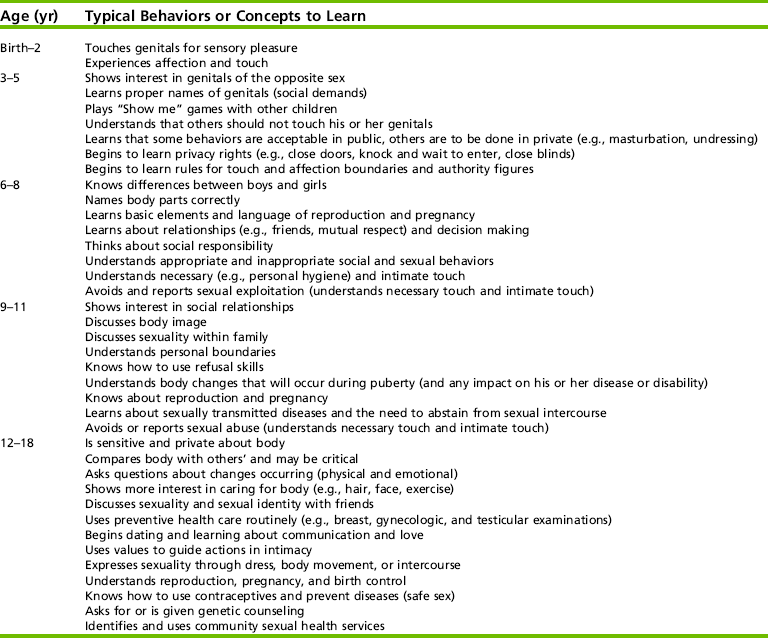

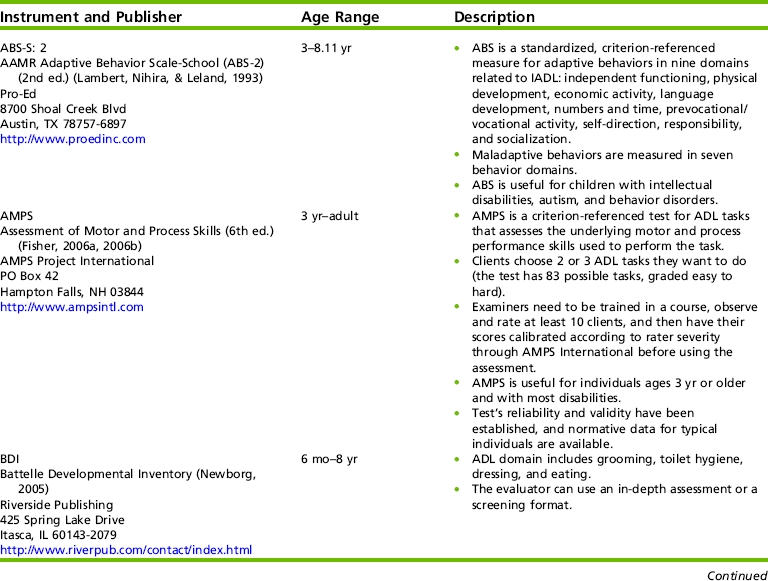

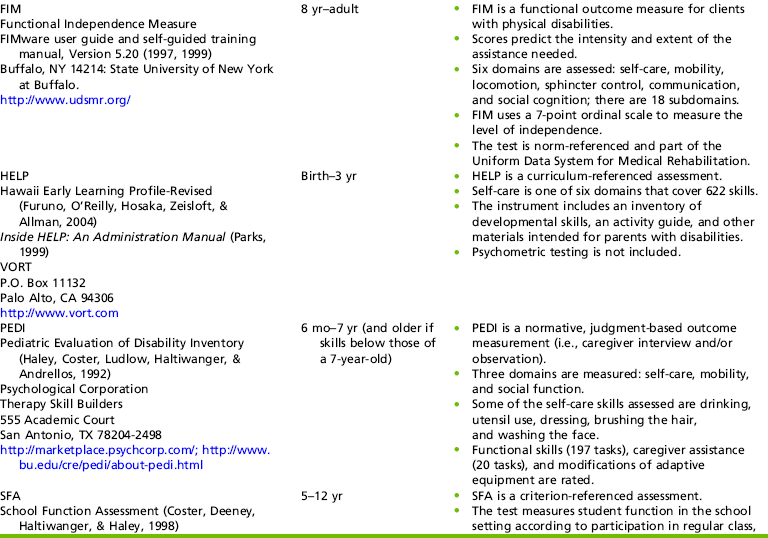

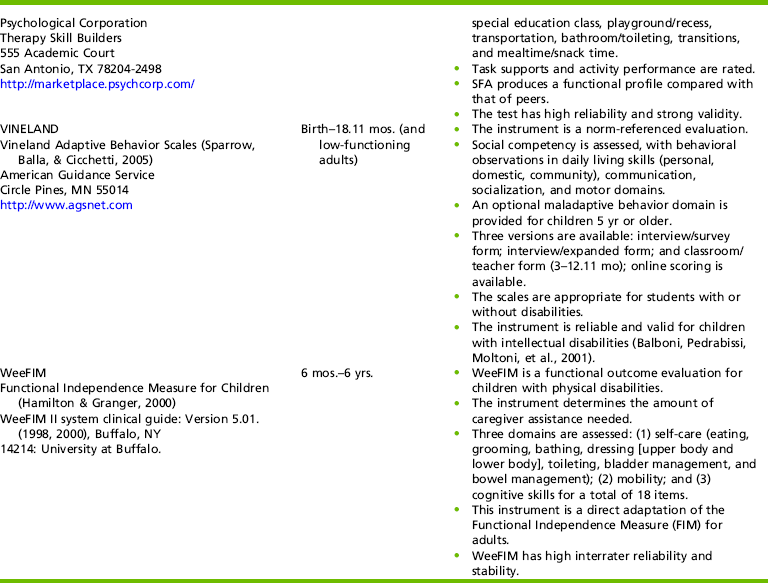

Evaluation of ADL begins with an analysis of occupational performance, which may involve collecting data from numerous sources. Interviews, inventories, and structured and naturalistic observations are evaluation methods typically used to measure ADL performance in occupational therapy. The therapist uses these methods alone or in combination to analyze occupational performance (abilities and limitations), develop collaborative goals with children and their families, plan intervention strategies, and/or measure outcomes of treatment. The choice of instrument depends on the reason for the evaluation. Table 16-1 lists some instruments that assess children’s ADL performance for different purposes. Each instrument can be rated by interviewing the caregiver or can be completed as an inventory. Each instrument (except the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales) can also be completed through observation of the child’s performance.

For ADL independence, the child must not only complete the task but also obtain and use the supplies the task requires. The therapist generally rates performance according to the child’s ability to set up and complete a task and may assess performance by grading the child’s level of independence. Table 16-2 presents one example of how the therapist may rate a child’s independence in bathing. The therapist may use a system for grading the child’s level of independence with any of the methods or purposes discussed next.

TABLE 16-2

Rating of Self-Care Skill Independence during Task Analysis

| Level of Independence | Definition | Bathing Example |

| Independent | Child does 100% of the task, including setup. | Child gets out needed supplies and equipment and bathes, rinses, and dries himself or herself without assistance. |

| Independent with setup | After another person sets up the task; child does 100% of the task. | Caregiver places bathtub seat in tub and organizes bath supplies; child bathes, rinses, and dries himself or herself without assistance. |

| Supervision | Child performs task by himself or herself but cannot be safely left alone; he or she may need verbal cueing or physical prompts for 1%–24% of task. | Child bathes, rinses, and dries himself or herself without assistance but needs monitoring when getting into and out of tub and when washing lower extremities because of poor balance and judgment. |

| Minimal assistance or skillful | Child does 51%–75% of task independently but needs physical assistance or other cueing for at least 25% of task. | Child bathes and rinses body parts independently but needs physical assistance getting into and out of tub; he or she is cued to monitor water temperature and to dry body parts. |

| Moderate assistance (26%-50% partial participation) | Child does 26%–50% of task independently but needs physical assistance or other cueing for at least 50% of task. | Child adjusts water temperature and washes and rinses face, torso, and upper extremities independently; he or she needs physical assistance getting into and out of tub and for washing and rinsing lower extremities and back. |

| Maximal assistance (1%-25% partial participation) | Child does 1%–25% of task independently but needs physical assistance or other cueing for 75% of task. | Child independently washes, rinses, and dries face but needs verbal cues to wash torso; he or she needs physical assistance getting into and out of tub and for washing other body parts. |

| Dependent | Child is unable to do any part of the task. | Caregiver physically picks up child, places him or her in tub, and washes, rinses, and dries child’s body parts; child does not lift body parts to be washed or dried. |

Modified from Trombly, C. A., & Quintana, L. A. (1989). Activities of daily living. In C. A. Trombly (Ed.), Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction (3rd ed., p. 387). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

An occupational analysis is done both during evaluation procedures and after they have been completed. Rogers, Holm, and Stone suggested that therapists collect four types of data when evaluating ADL performance: (1) precise identification of limitations in the task, (2) causes of limitations, (3) capacity for change, and (4) possible interventions needed.122 For example, when a child puts on socks, the therapist identifies that pulling the sock up over the ankle is difficult because of problems with upper extremity weakness and the tightness of the sock. Because the child has a neuromuscular disease with progressive weakness, the capacity to get stronger is absent; therefore, changes in the activity demands or compensatory techniques (e.g., loose-fitting socks or a sock aid) will be needed to enable the child to complete this activity independently. These data help therapists identify appropriate strategies and outcomes in intervention.

Interviews may be informal and unstructured. For example, the therapist may ask the interviewee (e.g., parent, child, teacher, or other significant caregiver) about the child’s goals and dreams, abilities, performance patterns (habits, routines, and roles), and characteristics of the environment in which the ADL task occurs. Sometimes simply asking the child, “What do you want to be able to do?” gives the therapist a place to start for further evaluation. The therapist may use interviewing techniques and inventory methods together to obtain useful information about how the child performs in different contexts.

Therapists also commonly use two types of observation. With structured observation, the therapist gives the child a task to do and then rates the child’s performance in completing it. Structured observation of ADL performance provides information about how well the child performs the task in a structured situation; however, it does not determine whether the child will begin the task at the appropriate time or perform the task in different contexts (e.g., whether the child will dress himself or herself when left alone).

With naturalistic or ecologic observation, the therapist gathers information in the typical or natural setting in which the activity occurs. Usually the therapist completes a task analysis to identify the activity demands. This includes looking at the steps of the activity, the sequence of these steps, and how the child adapts to the demands of the environment. In a naturalistic task analysis, the therapist evaluates the child’s ability to do the task itself and the physical, social, and cultural characteristics of the environment. For example, when observing a child’s ability to use the toilet at school, the therapist notes accessibility barriers and the sensory characteristics of the environment. How the child adapts to these factors, the typical classroom routines and expectations for toileting, and any cultural aspects of the toileting process (e.g., type of clothing the child is wearing; which hand is acceptable for wiping) are also noted. After identifying these contexts and the steps and sequence needed to complete the task, the therapist chooses appropriate intervention strategies according to the demands of the activity in the school context. Environmental observation is time consuming, but it provides an abundance of information when used in a team effort.119 In addition to evaluating the performance skills and patterns used, the therapist identifies the level of assistance and the number of modifications needed to improve the child’s independence.

Ecologic or environmentally referenced assessments are appropriate for all children and are particularly useful for children with moderate to severe disabilities who have difficulty generalizing tasks from one environment to another.111,153 A top-down approach considers the contexts in which the child performs valued occupations in addition to what the child can or cannot perform.16,25,68 With this approach, the therapist:

• Asks the parent and child what they want or need to do

• Identifies the environments or context in which the task occurs, the steps of the task, and the child’s capabilities

• Compares the demands of the task with the child’s actual performance skills while completing the task

• Identifies and prioritizes the discrepancies to develop an intervention plan

Team Evaluations

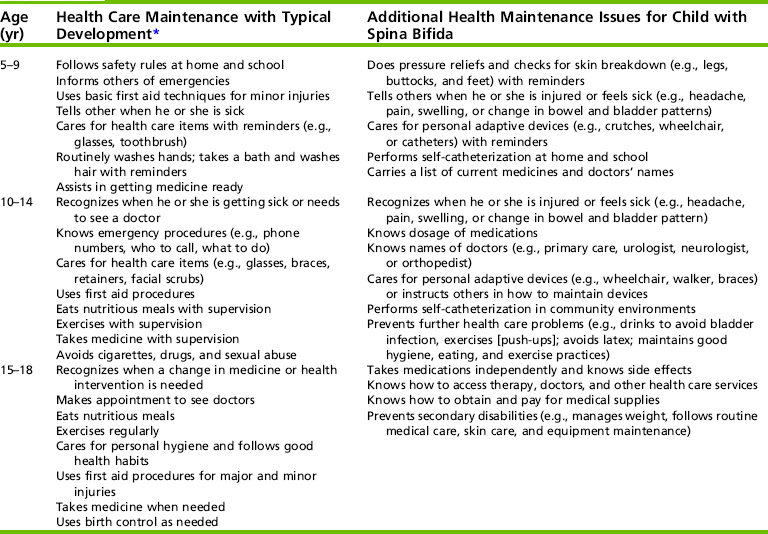

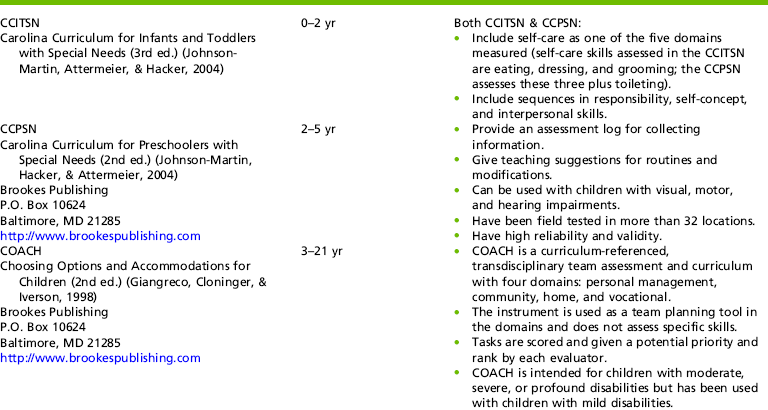

Curriculum-referenced or curriculum-guided assessments are often used by interdisciplinary teams in settings such as early intervention or school system practice. Self-care is often an area of assessment. The Carolina Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers with Special Needs (CCITSN),73 the Carolina Curriculum for Preschoolers with Special Needs (CCPSN),74 and the Hawaii Early Learning Profile49 are typical curriculum-referenced assessments used in early intervention. Others are listed in Table 16-1.

Giangreco et al. developed a useful transdisciplinary, curriculum-based assessment and guide, Choosing Options and Accommodations for Children (COACH).54 Therapists use COACH to identify areas of concern (not specific skills) for school-aged children with moderate to severe disabilities and to help plan inclusive educational goals with a family prioritization interview and environmental observations. The team identifies priorities, outcomes, and needed supports for specific environments and across environments in the areas of communication, socialization, personal management, leisure and recreation, and applied academics. Team members plan goals together, write interdisciplinary goals, and then decide which services the child needs. The team may decide that an occupational therapist is needed only as a consultant if the special education teacher is able to address the ADL task adequately.

Measurement of Outcomes

Health care and educational systems are demanding evidence-based practice and cost-effectiveness for therapy intervention. Within the past decade, professionals in the fields of rehabilitation and occupational therapy have developed universal assessments to measure the outcomes of therapy designed to enhance ADL skills (see Table 16-1). Outcomes may include improved occupational performance, adaptation, role competence, health and wellness, satisfaction, prevention, or self-determination/self-advocacy.1 In addition to providing a means to evaluate children individually, the collection of aggregated ADL assessment results or outcome measures can help justify program expansion or changes in intervention strategies.

In rehabilitation, four primary assessments, which are valid and reliable, are used to measure occupational performance and adaptation to ADL tasks in children and adolescents. The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is a universal assessment tool developed for adults but also used for children as young as 8 years old.48 The FIM assesses the severity of a disability and outcome progress after rehabilitation. For children 7 years of age or younger, therapists use the Functional Independence Measure-II for Children (WeeFIM-II).61,145 The Pediatric Evaluation of Disabilities Inventory (PEDI)59 is used for children from birth to 7 years of age and has a computer version for scoring.27 Numerous studies have used these assessment tools to demonstrate positive outcomes in ADL performance for children with brain injuries and other physical disabilities.6,7,34,86,88 However, the question arises whether a change in an assessment score really means that the child has made significant functional gains in self-care. Haley, Watkins, and Dumas found that occupational therapists, physical therapists, and speech therapists who were blinded to PEDI scores rated the magnitude of functional change in those scores as meaningful when an 11% change had occurred.60 In a study by Ziviani et al.,154 the WeeFIM and the PEDI appeared to measure the same construct of self-care, yet Kothari, Haley, Gill-Body, and Dumas suggest the PEDI was better suited to measure outcomes in children with brain injury.88 The choice of which assessment to use depends on the characteristics of the child and the context for intervention.

The Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) assesses ADL and IADL performance skills in various environments, both familiar (home or school) and unfamiliar (occupational therapy clinic).43,44 It has been used with children more than 3 years of age from different cultural backgrounds and with an array of disabilities. The AMPS has been used widely in outcome studies, mostly with adolescents and adults; however, it is also appropriate for children.43,55,113,114,130 In the AMPS, the therapist assesses the dynamic interaction of process and motor skills while the child attempts to meet the demands of the activity in a certain environment. The therapist has a choice of 83 ADL/IADL tasks and gives the child or adolescent a list of approximately 5 to 6 familiar tasks, from which the child chooses 2 to complete. Because the AMPS has a task–challenge hierarchy from very easy to much harder than average, many of the activities are appropriate for children (e.g., putting on socks and shoes, brushing the teeth, folding laundry, setting a table, upper and lower body dressing, making a sandwich, vacuuming, baking brownies, or cooking an omelet). While the child performs the chosen task according to the instructions given, the therapist rates the 16 ADL motor and 20 ADL process skills. The AMPS tasks use a top-down approach that gives a comprehensive view of how efficiently, safely, and independently the child is functioning in performance contexts.16,43,44 These results help the therapist predict what other ADL the child may or may not be able to perform. The AMPS has potential for evaluating progress over time after clients have been taught adaptive patterns, organizational strategies, and environmental modifications. In a study that compared children with attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder with typical children, Prudhomme-White and Mulligan found the AMPS to be sensitive in identifying deficits in motor and process skills, which may help therapists identify intervention needs (e.g., coordination, calibration, sequencing, memory).116 A limitation of the AMPS is that the rater must be trained in a 5-day course; then after observing and rating clients, his or her scoring is calibrated according to rater severity. This training and calibration must occur before the assessment is given.

School therapists may not find the PEDI, WeeFIM-II, or FIM to be a useful outcome assessment of school performance. As discussed in Chapter 24, the School Function Assessment (SFA) evaluates the child’s participation in six different environments—transportation, transitions, classroom, cafeteria, bathroom, and playground.26 This assessment gives the therapist a profile of valuable information about self-care performance and role performance in the school environment, which the therapist uses to develop individualized education program (IEP) outcomes. For the School AMPS, the therapist observes the child in the natural school environment while the child does typical school tasks.46 Currently, the assessment includes 20 possible school tasks in five categories: pen/pencil writing tasks, drawing and coloring tasks, cutting and pasting tasks, computer writing tasks, and manipulative tasks.41,45,47,56,108 The School AMPS helps therapists assess motor and process skills during typical school graphic communication and communication device tasks. Because modifications to ADL tasks often involve assistive technology (AT), it is important that the therapist consider the emerging outcome AT assessments in this area related to satisfaction and performance (see Chapter 20).

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) assesses a client’s perception of his or her ADL skills, productivity, and leisure occupations over time and is useful for assessment and reassessment.93 The COPM provides an interview framework for children and families to identify how they are performing in everyday occupations and environments and how satisfied they are with their performance. Personal care, functional mobility, and community management are the areas covered in ADL performance, and a structured scoring system is used. The child identifies his or her most important concern and rates his or her performance and satisfaction with that task; this helps the child prioritize intervention goals.93,101 This self-assessment piece makes the COPM more appropriate for children older than 8 years of age.93

The Child Occupation Self Assessment (COSA) is a self-rating tool that a child uses to describe his or her competence (“How well I do the task?”) and the importance or value of doing a task (“How important is this to me?”) in school, home, and community settings.81 Observations of ADL and IADL tasks, as well as managing emotions and cognitive tasks, are part of this assessment. There are two versions available: a checklist with visual symbols and a card sort version. For example, one item is “Keep my body clean.” The child then rates how well he or she does the task and how important it is to him or her. This tool has good content, structural, and external validity when used with children 6 to 17 years of age but should be used with caution in assessing younger children and children with intellectual disabilities.89 This tool helps therapists target intervention, which may or may not include self-care tasks.

Another method to measure outcomes in ADL performance is using goal attainment scaling (GAS). GAS was originally developed for adult clients in mental health settings84 and is currently used by pediatric occupational therapists.30,83,92,98,104,107 This method allows the child, family, and therapist to set goals and criteria for success. Kiresuk, Smith, and Cardillo recommend using a 5-point scale.84 To document progress, baseline behavior is scaled and described as 0 or performance expected, +1 for better than expected performance, and +2 for much better than expected performance. To describe a lack of progress or a decrease in capabilities, behavior is scored −1 for less than expected performance or −2 for much less than expected performance.100 It is suggested that GAS is appropriate for children with moderate to severe disabilities or for children who make small gains in performance such as those in sensory integration treatment.98 It is an appropriate outcome measurement tool if standardized testing is not available or if outcomes are variable.84,100 Before intervention, outcome measures are defined after talking with the child and family to find out what type of change would be meaningful. Data are collected over time and then goals are modified for incremental differences. Mailloux and colleagues suggest that GAS may be used across clinical sites for research outcomes.98 Research Note 16-1 describes a review of the literature on GAS in pediatric rehabilitation139 and gives suggestions for using GAS.

INTERVENTION STRATEGIES AND APPROACHES

When planning intervention procedures, the therapist considers the child’s characteristics and performance skills and patterns in relation to the context and demands of the activity. Therapists need to be sensitive to parents’ and other caregivers’ needs and concerns. It is helpful to listen to and reassure these individuals while engaging them in observations and problem solving. When planning treatment for children with performance problems in ADLs, the therapist must ask himself or herself the following questions14,136:

• What ADL are useful and meaningful in current and future contexts?

• What are the preferences of the child and/or the family?

• Are the activities age appropriate (i.e., used by peers without disabilities)?

• Is it realistic to expect the child to perform or master this task?

• What alternative methods can the child use to perform tasks (e.g., including the use of activity modifications or assistive technology)?

• Does learning this task improve the child’s health, safety, and social participation?

• Do cultural issues influence how tasks are taught?

• Can the task be assessed, taught, and practiced in a variety of environments?

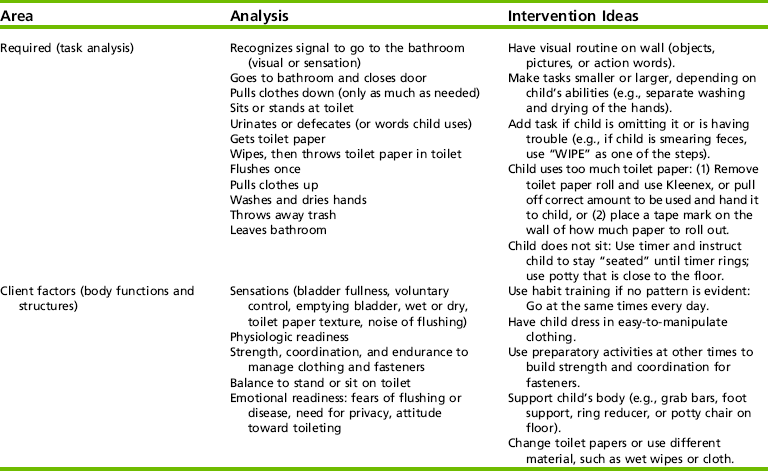

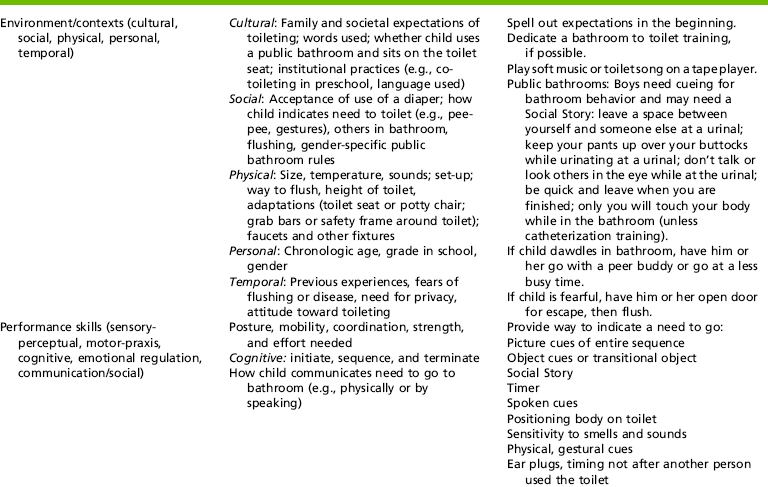

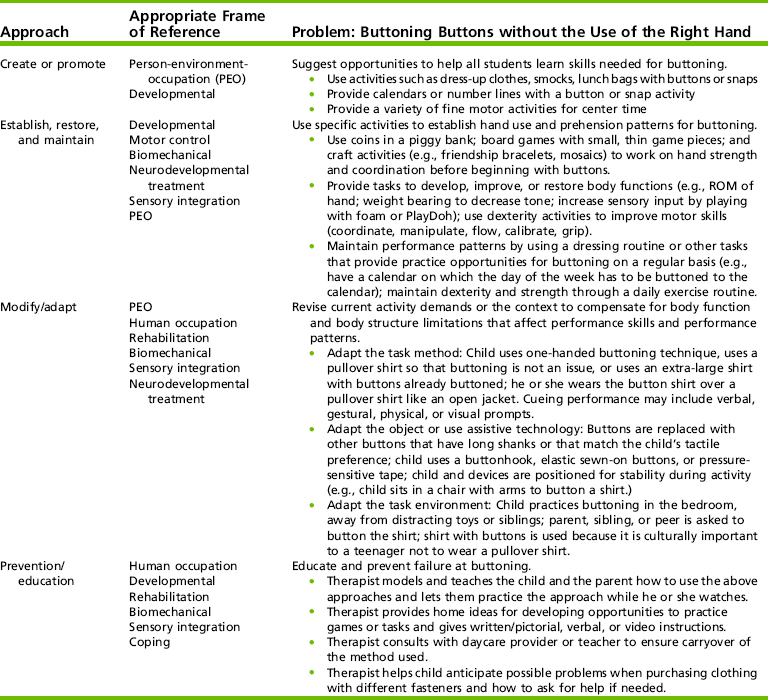

Therapists use various approaches to improve ADL skills in children, including (1) promoting or creating; (2) establishing, restoring, and maintaining performance; (3) modifying or adapting the task, method, and/or environment; and (4) preventing problems/educating others.1 Therapists often use a combination of these approaches and various theoretic orientations to help children participate in ADL occupations. Table 16-3 gives examples of these approaches and possible theoretical orientations for the therapist to use when teaching a child to button his or her shirt. These approaches are discussed throughout each area of ADL tasks in later sections of the chapter.

TABLE 16-3

Approaches to Improving the Performance of Activities of Daily Living

Modified from American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). (2008). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 625-683; and Dunn, W., Brown, C., & McGuigan, A. (1994). Ecology of human performance: A framework for considering the effect of context. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48(7), 595-607.

Promoting or Creating Supports

Therapists often create supports within the environment that offer all children the opportunity to engage in ADL occupations that are age-appropriate and not related to a disability status.1 This approach offers team or system supports for schools without focusing on the child with a disability.62 When using this approach, therapists design a program in which school or community groups participate. Possible activities include creating a module or center activity requiring zipping, snapping, and/or buttoning; developing a box of fine motor/self-care activities to distribute to all kindergarten classrooms in the district; giving an in-service presentation to the church or school about self-care development; or participating as a building committee member to make recommendations about universal design for the new bathrooms or gyms being built. When working with families, therapists may promote opportunities for everyone to participate in using a morning checklist for self-care routines. Perhaps a visual picture board will help all the children in the family to understand what tasks are needed for a morning routine.

Establishing, Restoring, and Maintaining Performance

The therapist may attempt to establish ADL performance and patterns using a developmental approach or, if this is not possible, may try to restore or remediate the child’s abilities that interfere with performance. To establish ADL patterns, the therapist establishes the child’s developmental and chronologic age and plans treatment according to a typical developmental sequence. In this approach, the therapist examines underlying body structures and functions (e.g., strength, tactile discrimination), selects age-appropriate tasks and habits to target in intervention, and gives parents some expectations for skill development.67 For children with hemiplegia, constraint-induced therapy may establish or restore movement and use of the weaker upper extremity while the other extremity is casted.114

In interventions to establish or restore performance, therapists identify gaps in skills and intervene to teach or remediate the underlying problem that is interfering with a child’s ADL performance. This approach focuses on the child’s deficits in body function and structure to perform ADL activities. Therapists often use biomechanical, motor control, cognitive orientation, neurodevelopmental therapy (NDT), sensory integration, or behavioral approaches to restore performance skills. For preschoolers with moderate fine motor delays, some ways to increase self-care skills are to provide play and targeted fine motor and praxis interventions, which require in-hand manipulation, grasp strength, and eye-hand coordination.19 Using an NDT approach, the therapist begins with preparatory handling techniques to inhibit the tone before dressing a child with spastic cerebral palsy and tight extensors. In this instance, the therapist places the child in a supine position and slowly rolls the child’s hips from one side to the other to reduce the tone, increase ROM, and encourage trunk rotation. After preparation improves the child’s task performance, the therapist facilitates movement patterns by stabilizing the pelvis while the child pulls up his or her pants. When using this approach, therapists provide parents and children with suggestions on how to practice these movement patterns in various tasks.

In a motor learning approach, a child may learn how to put on shoes through practicing the whole task in a variety of activities (e.g., dress up, relay races, morning dressing routine) or environments (e.g., home, school, therapy session, gym class). During practice, the child receives specific feedback (e.g., “pull the back of the shoe up when pushing the heel down in the shoe”). Jarus and Ratzon found that mental practice increased acquisition of new bimanual motor skills for children faster than just physical practice.72 This technique may also help children acquire ADL skills (e.g., mental rehearsal of putting the shoe on the foot).

Mobility Opportunities Via Education (M.O.V.E.) is a structured interdisciplinary program that helps establish and restore sitting, standing, and walking skills for children with severe motor limitations.11 The M.O.V.E. team plans and provides motor intervention using a motor control or task-oriented approach. Primary goals are eating, toileting, and motor skills; progress is monitored and goals are updated through systematic data collection.11,144,151 Child-centered goal setting helps the team target functional outcomes (e.g., to stand to pull up pants at the toilet). Activities are used to develop ADL skills for the context in which they are used. Teams are trained together, and it is often difficult to distinguish between therapists and teachers. This approach is used with persons in any age group with moderate to severe motor limitations and is appropriate for children with and without intellectual impairments. Many case studies and testimonials on the M.O.V.E. web site (http://www.move-international.org/) and a few research studies support the effectiveness of this program.11,151

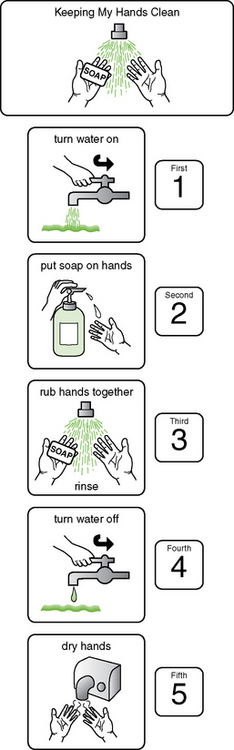

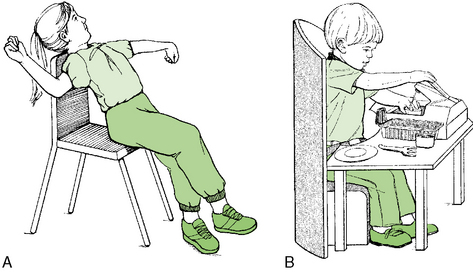

Occupational therapists also use behavioral approaches to establish and restore ADL skills. They may use backward or forward chaining to teach the tasks. In backward chaining, the therapist performs most of the task, and the child performs the last step of a sequence to receive positive reinforcement for completing the task. Practice continues, with the therapist performing fewer steps and the child completing additional steps. This method is particularly helpful for children with a low frustration tolerance or poor self-esteem because it gives immediate success. In forward chaining, the child begins with the first step of the task sequence, then the second step, and continues learning steps of the task in a sequential order until he or she performs all steps in the task. Forward chaining is helpful for children who have difficulty with sequencing and generalizing activities. The therapist gives varying numbers of cues, or prompts, before or during an activity. Therapist or person cues and environment or task cues may occur naturally or artificially in an environment. Therapists use verbal, gestural, or physical cues or a combination of all three.12,137 Environmental or task cues may include picture sequences or checklists, color coding, positioning, or modifying the sensory properties of the environment or materials used in a task. Figure 16-2 shows an example of a visual picture sequence for hand washing. Reese and Snell described a hierarchical approach to presenting artificial cues from least intrusive (verbal cues), to more intrusive (verbal and gestural cues), to most intrusive (verbal and physical cues).118 For example, they described this hierarchy of physical cues: (1) shadowing the child’s movements, (2) using two fingers to guide the child, and (3) using a hand-over-hand approach to guide movement. The therapist or the parent uses the fewest cues necessary and fades cues to promote independence. Figure 16-3 presents examples of these different types of cues, which can be used as a child performs various self-care occupations. Research Note 16-2 presents a review of studies that used different cues for persons with severe and profound disabilities and gives practical suggestions to consider.90

FIGURE 16-2 This simple picture sequence gives Adam the needed cues to wash his hands independently. Courtesy Judith Schoonover, Loudoun County Public Schools, Virginia; Picture Communication Symbols from Mayer-Johnson, Inc, Solana Beach, CA.

FIGURE 16-3 Hierarchy of cues, from most intrusive to least intrusive. A, A hand-over-hand approach is used for squirting soap onto the child’s hands. B, Two fingers are used to guide zipping of the child’s coat. C, The therapist shadows her hand over the top of the child’s hands to cue hand movements for hand washing. D, The therapist verbally cues the child on how to wash the hands.

Once self-care routines and patterns are developed, it is important to maintain them and any of the environmental supports that promote continued ADL success. Repetition and the development of habits and routines are essential organizers, particularly for children who take a long time to learn new skills, have poor memory, or thrive on routine or practice. Schedules for toileting or dressing, visual prompts displayed on the wall, a set place for items when grooming, and a checklist for how to clean a splint or contacts are all examples of contextual supports. Health maintenance activities (e.g., self-catheterization, wheelchair push-ups, ROM exercises, taking medication regularly, and eating nutritious meals) support task performance in all occupations, including ADLs such as maintaining a bowel and bladder routine, transferring to the toilet, and dressing.

Adapting the Task or Environment

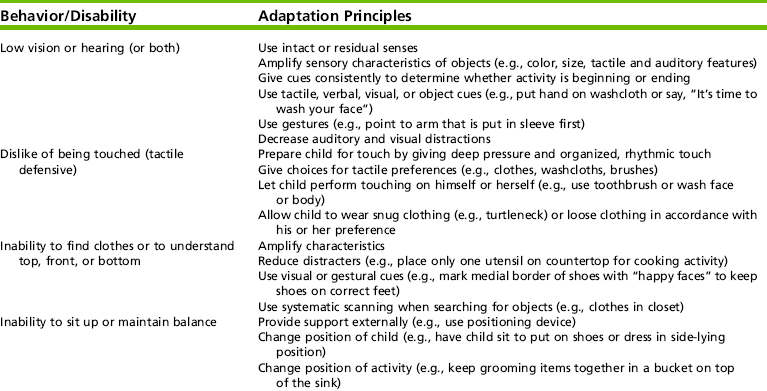

When adapting or modifying an activity (i.e., using a compensatory approach), the therapist uses alternative physical techniques, substitute movement patterns, or other adaptive performance patterns to enable the child to complete a task. Adaptation strategies may include modification of the task or task method, use of assistive technology, or modification of the environment. Therapists often use a combination of these strategies to improve a child’s performance, considering the performance context. Table 16-4 provides examples of typical adaptation approaches used with different functional problems in ADLs.

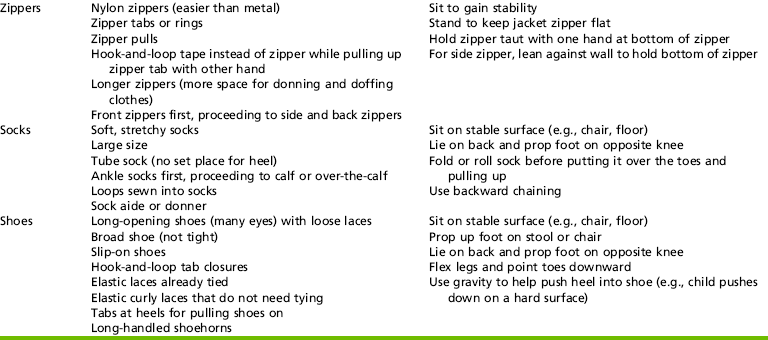

TABLE 16-4

Typical Adaptation Principles Used with Children and Adolescents with Disabilities

Developed from Geyer, L. A., Kurtz, L. A., & Byram, L. E. (1998). Prompting function in daily living skills. In J. P. Dormans & L. Peliegrino (Eds.), Caring for children with cerebral palsy: A team approach (pp. 323-346). Baltimore: Brookes; and Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., Kellegrew, D., & Mullen, K. (1996). Parent education for prevention and reduction of severe problem behaviors. In L. K. Koege, R. L. Koegel, & G. Dunlap (Eds.), Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community (pp. 3-30). Baltimore: Brookes.

Therapists practice adaptation or compensatory strategies in various contexts and modify them until they become functional. For example, a child with a bilateral upper extremity amputation may use several compensatory strategies for ADL tasks. As an adapted method, the child may use the feet or mouth to write or dress, or may learn new movement patterns to operate a prosthetic arm (assistive device) for manipulating objects. Adapting the social environment by using a personal assistant or peer in the home or school environment is another adaptation strategy. Modification of the bedroom setup for easier accessibility and placement of clothes in lower drawers that are reachable from a wheelchair are other possibilities.

Adapting or Modifying Task Methods

The therapist often modifies tasks by using grading techniques. Grading is the adaptation of a task or portions of a task to fit the child’s capabilities. By using a task analysis, the therapist rates subtasks of the activity and varies them according to their degree of ease or difficulty for the child. The therapist may modify the activity demands to compensate for limited capacities and performance skills. He or she may grade the tasks according to specific qualities (e.g., simple to complex). Grading a task may include gradually increasing the number of steps for which the child is responsible, fading the amount of personal assistance or cueing the child receives, or reducing the strength needed or length of time the child takes to complete an activity.

Each ADL involves a series of steps that are performed together in a specific sequence. Through task analysis, the therapist gains an understanding of the sequence of steps involved in each ADL task. When a child cannot complete a task independently or when completion of the task requires too much of the child’s energy, therapists may suggest personal assistance, which the child directs.135 The therapist uses partial participation when a child cannot complete a task independently. The child performs some steps of the task, and a caregiver completes the remaining steps. This helps the child become part of the activity and use his or her current abilities. Partial participation is often used when children are first learning a task or when their abilities are severely limited.39,58

Adapting the Task Object or Using Assistive Technology

Several assistive devices are available through equipment vendors, catalogs, and specialty department stores. These devices are changing constantly, and they vary in complexity, price, and quality. Assistive devices are commercially available or are custom-made by the therapist, skilled orthotists, or rehabilitation engineers. By using local and national databases, publications, and Internet searches on product comparison, therapists keep informed of the availability of new assistive devices to find equipment for unique or specific problems.

The choice of an assistive device is a cooperative decision made by the child, the parents, therapists, and others who work with the child.24 Together, these individuals systematically evaluate what the child needs to do, his or her performance contexts, the child’s abilities and limitations, and the capabilities of the device itself. They choose the device that has the best “environmental fit.” When the device arrives, student, family, and staff are taught to use it to eliminate unnecessary trials or frustrations. At this time, attitudes about the device are addressed (e.g., “This is too difficult to learn.”) by providing support and education. Adolescents who are striving to identify with their peers tend to reject devices that call attention to their disabilities. Children are easily frustrated if use of the device requires skills that exceed their coordination abilities or attention span.

To be worthwhile, an assistive device should meet the following requirements:

• Assist in the task the child is trying to complete without being cumbersome

• Be acceptable to the child and family and in the contextual environments in which it will be used (e.g., in terms of appearance, functions, upkeep, storage, and amount of time to set up or learn how to use the device)

• Be practical and flexible for the environments in which it will be used (e.g., have acceptable dimensions, portability, positioning, and be usable with other assistive devices)

• Be durable and easy to clean

• Be expandable (i.e., able to meet the child’s needs now and when the child has grown and has more sophisticated abilities)

• Be safe for the child to use (e.g., physical, behavioral, or cognitive child factors such as drooling, throwing, or difficulty with sequencing do not interfere with use of the device)

• Have a system of maintenance or replacement with continued use

• Meet the cost constraints of the family or purchasing agency

Overall, the child should complete tasks at a higher level of efficiency using the device than he or she could without it. Trial use of a device is highly recommended; this helps determine the feasibility of its use and demonstrates its value to the child and primary caregivers. Caregiver roles are lightened by using assistive devices and modifications.112

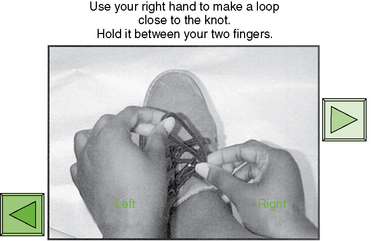

Recently, computers and cognitive prosthetic devices have come into use to give children the visual and/or auditory prompts needed to initiate, sequence, sustain, and terminate ADL and work activities.31,52,57 For example, a “talking book” from Microsoft’s PowerPoint helps a child learn how to tie a shoe, how to dress himself or herself, and how to set a table if the technology is nearby. As shown in Figure 16-4, for tying shoelaces, the child or adolescent uses the talking book as a visual and auditory prompt on his or her computer or PDA. Other cognitive prosthetic devices that aid ADL tasks include portable memory aids (e.g., checklists, voice-activated tape recorders), medication alarm pill boxes, watches with specialized features (alarms, schedules, talking), alarm organizers, pagers, sound-activated key rings, and simple switches that program up to three steps.

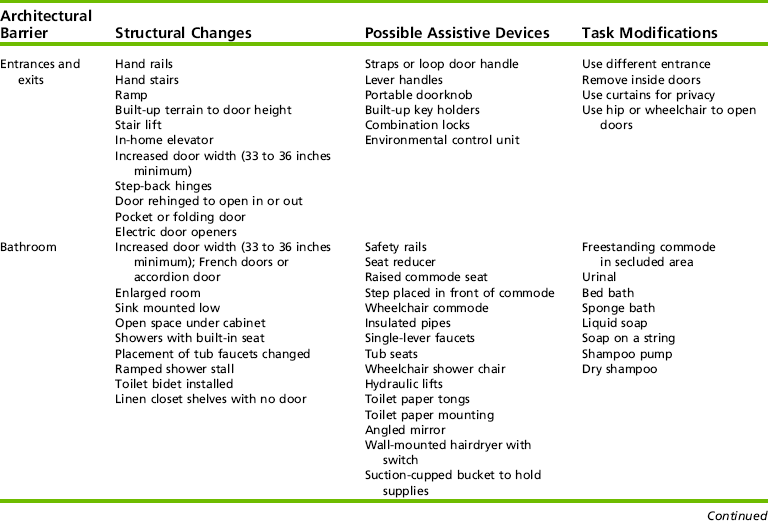

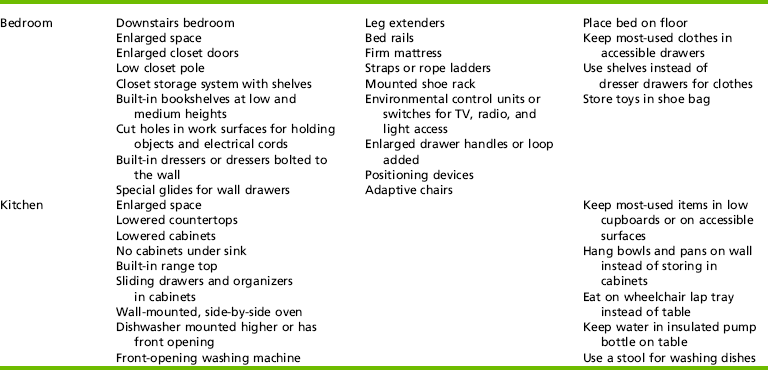

Adapting the Physical Environment

In all of the approaches discussed, the therapist uses the interaction among the child, the environment, and the contexts to improve performance. Physical environments are adapted by changing the nonhuman characteristics of the environment. This may include simple modifications to the lighting, floor surface, amount and type of furniture or objects, and the overall traffic pattern of the room or building. Sometimes, modifications for architectural and other physical barriers or sensory characteristics are recommended. To facilitate wheelchair access, ramps are installed or furniture may be moved. For example, the family places the computer on a more usable work surface in a more accessible location so that the child who is wheelchair dependent uses it for doing homework or communicating with a brother or sister at college. For some children, therapists minimize sensory stimuli and eliminate visual and auditory distractions. Other children may require increased environmental stimulation (e.g., color or music) to cue their performance. Table 16-5 presents adaptation examples of the physical environment.

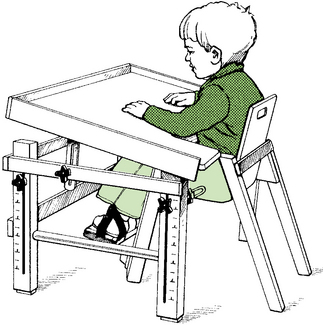

Work Surface: The work surface supports the child, materials, tools, and assistive devices in an activity. The boundaries of the workspace help children keep within usable or safe environments. For example, a cutout surface on a table or a lip on a wheelchair tray or sink countertop can serve as a boundary. The therapist adds various textures, colors, and pictures to the work surface area to give sensory cues about boundaries or to structure the task. Even with these modifications, some children (e.g., those with weakness in one side of the body) need assistance in stabilizing objects. Table 16-6 presents suggestions for stabilizing objects when they are placed on the work surface or held by the child.

TABLE 16-6

Stabilization Materials and Application Procedures

| Material | Application Procedures |

| Tape | Applies quickly but often is a temporary solution; includes masking, electrical, and duct tapes (duct tape is sturdy and has holding power). |

| Nonslip pressure-sensitive matting | Fits under objects or around them and can be glued to objects; friction between materials minimizes slipping and sliding of objects; available in rolls or pads. |

| Suction cup holders | Hold lightweight materials, maintaining suction between object and work surface; single-faced suction cups can be applied permanently to objects (e.g., with nails, screws, or glue); double-faced suction cups can be moved from object to object. |

| C-clamps | Secure flat objects to lap trays, table edges, and other surfaces. |

| Tacking putty | Sticks posters onto walls; holds lightweight objects on surfaces such as tables, lap trays, angle boards, and walls. |

| Pressure-sensitive hook-and-loop tape (Velcro) | Sewn to cloth or glued to the base of objects and work surfaces; soft loop tape is used on areas that will contact the child’s skin or clothing. |

| Wing nuts and bolts | Secure objects to a table surface or lapboard when holes are drilled through the object and holding surface; sturdy and more permanent. |

| Magnets | Affix to an object; stabilize objects on metallic surfaces such as refrigerator doors, metal tables, and magnetic message boards. |

| L-brackets | Hold objects in an upright plane; holes are drilled in both the work surface and the object to correspond with the L-bracket holes; objects are secured with nuts and bolts. |

| Soldering clamps | Hold small items for intricate work (e.g., mending a shirt, sewing on a button, or putting on a bracelet); mounted to freestanding base; bases are weighted, suction cupped, or held to the surface with a C-clamp. |

| Elastic or webbing | Attach to or around objects or positioning devices to hold them down; they also secure flat objects straps onto a work surface; straps are secured by tying, pressure-sensitive hook-and-loop tape, D-rings and buckles, grommets, or screws. |

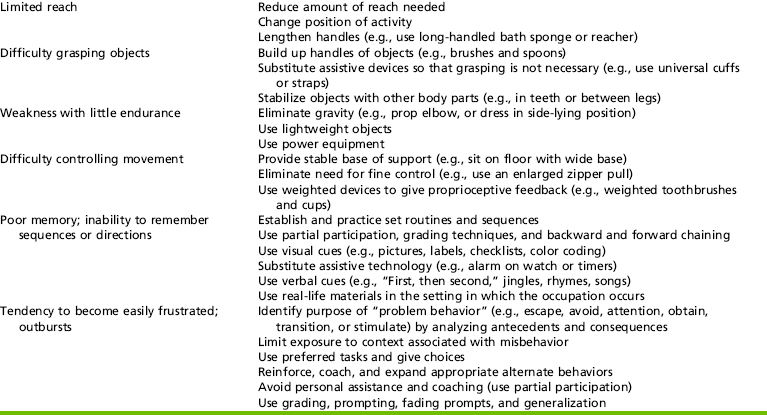

Characteristics of the work surface that are amenable to adaptation include height, angle of incline (Figure 16-5), size, distance from the body, distance from other work areas, and general accessibility. Changes in these characteristics enhance the child’s function in various ways, including improving arm support, increasing the visual orientation of a task, adapting seat height for easier transfers, and optimizing table height for wheelchair access.

Positioning: Therapists consider the position of the child and the position of the materials or activity when planning intervention. When possible, the therapist uses the most typical position for a given activity with the fewest restrictions or adaptations to stabilize the body for function.10,42 Children who have problems with posture and movement often lack sufficient control to assume or maintain stable postures during activity performance and thus benefit from adaptive positioning. Adaptive positioning may include using different positions (e.g., sitting instead of standing), low-technology devices (e.g., lapboards, pillows, towel rolls), or high-technology devices (e.g., customized cushions, wheelchairs, or orthotics). If an adaptive device or orthotic is used, the therapist needs to systematically consider whether the device assists or hinders ADL performance. Chafetz et al. found that some children wearing a thoracolumbosacral orthosis had better posture but actually performed less efficiently with dressing when wearing the orthosis.21

Alternative body positions are extremely helpful to children with disabilities. These changes help compensate for physical limitations in body functions such as strength, joint movement, control, or endurance and provide relief to skin areas and bony prominences. The therapist considers positions that maximize independent task performance. Key points for stability that enable the child to use available voluntary movement are the pelvis and trunk, head, and extremities.9,42 The following questions guide decision making about positioning:

• Is the child aligned properly? Are the hips, shoulders, and head in good alignment (Figure 16-6)?

FIGURE 16-6 Sitting postures. A, Incorrect sitting resulting from a massive extension pattern and an asymmetrical tonic reflex posture. B, Correct sitting posture. Weight is equally distributed on the sitting base, and the feet and elbows are supported.

• What positions or devices increase trunk stability (e.g., using a hard seat insert or lateral or orthotic supports, using a surface to support the feet, or widening the sitting base by abducting the legs)?

• Is support adequate to maintain upright posture with head in the midline?

• Can the child use his or her hands and visually focus on the task?

Sitting and sometimes standing are the most appropriate positions for the child to perform ADL tasks. In addition to postural alignment, the therapist recommends positions that provide the child with (1) good orientation of his or her body to the work surface and the materials being used; (2) good body and visual orientation to the therapist (if instruction is being given); and (3) the ability to independently get to the place where the ADL occurs, maintain the necessary position, and leave. The therapist modifies chair heights so that the child’s feet are touching the floor to support postural stability and facilitate transfers. If the therapist raises the seat height, a footrest is also provided. The therapist shortens or lengthens chair legs with blocks or leg extenders.

Kangas advocates a “task-ready position” for children with moderate to severe motor disabilities.77 Instead of positioning the child’s hips, knees, and ankles at 90-degree angles, Kangas positions them so that they are ready to move. In the task-ready position, the pelvis is secure, the trunk and head are slightly forward so that the shoulders are in front of the pelvis, the arms and hands are in front of the body, and the feet are flat on the floor or behind the knees. The therapist removes or loosens as many restraints or chair adaptations as safely possible so that the child has maximal potential for movement. Such movement, even when subtle, provides visual, vestibular, proprioceptive, and kinesthetic feedback. A carved or molded seat and a seat belt across the thighs give additional sensory feedback and are used for positioning the pelvis and for safety.

Prevention/Education

Problem Solving: Cognitive Approach

Anticipatory Problem Solving: Children learn and perform ADL tasks in a variety of environments, not just in the clinic or the typical place where the task occurs. Anticipatory problem solving is a preventive approach that prepares children and their families for those unexpected events that may occur during self-care occupations.124 Typically, parents do this with young children during toilet training. They anticipate the child will have accidents in the beginning and bring two changes of clothes in case this does occur. In a study by Bedell, Cohn, and Dumas, parents used anticipatory problem solving to help prevent meltdowns for their children with brain injuries.5 By thinking ahead (e.g., remembering not to have the child dressed in overalls on gym day; having children wear splints on the weekend and not during the week), parents ensure that their children can actively participate in school activities.

Children and youth also need to be part of anticipatory problem solving. By anticipating problems and generating solutions ahead of time, children can often reduce the anxiety they experience when trying a new task or entering a new environment.124 Using contextual cues,17 such as noticing the floor is wet in the bathroom, and practicing different scenarios may be helpful. Schultz-Krohn suggests asking the following questions124:

1. What is the task to be completed and where will it occur?

2. What are the objects needed to complete the task?

a. Are these objects available and ready to be used?

b. If the objects are not available (e.g., misplaced, broken, or being used by someone else), what else could be used and who and how will the child ask for help?

3. What safety risks or hazards are within the environment or related to the objects being used by this student or other students? How can these risks be avoided?

Planning a natural teaching incident to occur during an activity (sabotage)140 gives the child, caregivers, teachers, and therapists a good idea of how well the child can adapt and possibly use the anticipatory problem-solving solutions generated (Case Study 16-2). Giving the child an opportunity to choose a different way to complete or adapt a task promotes self-determination.