Community Care

The Family and Culture

• Describe the main characteristics of contemporary family forms.

• Identify key factors influencing family health.

• Compare theoretic approaches for working with childbearing families.

• Discuss cultural competence in relation to one’s own nursing practice.

• Identify key components of the community assessment process.

• List indicators of community health status and their relevance to perinatal health.

• Describe data sources and methods for obtaining information about community health status.

• Identify predisposing factors and characteristics of vulnerable populations.

• List the potential advantages and disadvantages of home visits.

• Explore telephonic nursing care options in perinatal nursing.

• Describe how home care fits into the maternity continuum of care.

• Discuss safety and infection control principles as they apply to the care of clients in their homes.

Introduction to Family, Culture, Community, and Home Care

The composition, structure, and function of the American family have changed dramatically in recent years, largely in response to economic, demographic, sociocultural, and technologic trends that influence family life and health. Despite current challenges in improving the overall health of the nation, there is widespread concern about family health and well-being as a reflection of individual, community, and national health status. Recent economic changes in society have prompted individuals and families to go without health insurance, thus providing yet another barrier to health care. In addition to facing significant barriers in accessing needed services women and families are faced with the challenge of overcoming discrimination in health care practices. As cultural diversity increases and demographics change, it is essential that nurses become culturally competent in order to provide sensitive and individualized care to women and their families (Cooper, Grywalski, Lamp, Newhouse, & Studlien, 2007).

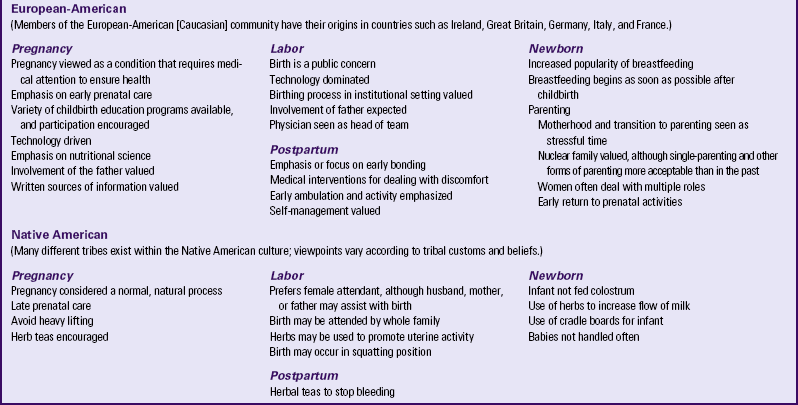

Trends in maternal and infant health in the United States reveal that progress has been made in relation to reduced infant and fetal deaths, and use of prenatal care (see Chapter 1), but notable gaps remain as the rates of low birth weight, preterm birth, and infant mortality have fallen short of Healthy People 2010 target goals, with persistent disparities between non-Hispanic whites and African-Americans (March of Dimes, 2009). Because many of these outcomes are preventable through access to prenatal care, the use of preventive health practices clearly demonstrates the need for comprehensive community-based care for mothers, infants, and families. As perinatal health trends emerge, nurses are assuming greater roles in assessing family health status and providing care across the perinatal continuum. This continuum begins with family planning and

continues with the following categories of care: preconception, prenatal, intrapartum, postpartum, newborn, interconception (between pregnancies), and the child from infancy to 1 year of age. In the community, health care ranges from individual care to group and community services, and from primary prevention to tertiary care experiences and home visiting. Depending on the needs of the individual family unit, independent self-management, ambulatory care, home care, low risk hospitalization, or specialized intensive care may be appropriate at different points along this continuum.

In community-based health care, both the aggregate (group of people who have shared characteristics) and the population become the focus of intervention. Health professionals are required not only to determine health priorities but also to develop successful plans of care to be delivered in the health clinic, the community health center, or the client’s home (Community Activity). This home and community-based delivery system presents unique challenges for perinatal and maternity nurses.

The Family in Cultural and Community Context

The family and its cultural context play an important role in defining the work of maternity nurses. It is therefore essential that nurses become culturally competent in order to provide the most efficient care possible. Despite modern stresses and strains, the family forms a social network that acts as a potent support system for its members. Family care-seeking behavior and relationships with providers are all influenced by culturally related health beliefs and values. Ultimately all of these factors have the power to affect maternal and child health outcomes. The current emphasis in working with families is on wellness and empowerment for families to achieve control over their lives.

Defining Family

The family has traditionally been viewed as the primary unit of socialization, the basic structural unit within a community. The family plays a pivotal role in health care, representing the primary target of health care delivery for maternal and newborn nurses. As one of society’s most important institutions, the family represents a primary social group that influences and is influenced by other people and institutions. There are a variety of family configurations.

Family Organization and Structure

The nuclear family has long represented the traditional American family in which male and female partners and their children live as an independent unit, sharing roles, responsibilities, and economic resources (Fig. 2-1). In contemporary society, this “idealized” family structure actually represents only a relatively small number of families, which is steadily decreasing in number.

Married-parent families (biologic or adoptive parents) account for approximately 64% of American families, representing 69% of Caucasian, 55% of Hispanic, and 26.6% of African-American families (Wherry & Finegold, 2004).

Many nuclear families have other relatives living in the same household.

Extended family members include grandparents, aunts, uncles, or other people related by blood (McEwen & Pullis, 2008) (Fig. 2-2). For some groups, such as African-American and Latin-American, extended family is an important resource in terms of preventive health behavior. Mexican-Americans account for the fastest growing minority population in the United States, and they rely on their family to make almost all decisions, including health care (Eggenberger, Grassley, & Restrepo, 2006). The extended family is becoming more common as American society ages. It is therefore important for nurses to recognize the desire for people of many cultures to include their family in making important decisions, and to do everything possible to make this happen.

Married-blended families, those formed as a result of divorce and remarriage, consist of unrelated family members (stepparents, stepchildren, and stepsiblings) who join to create a new household. These family groups frequently involve a biologic or adoptive parent whose spouse may or may not have adopted the child.

Cohabiting-parent families are those in which children live with two unmarried biologic parents or two adoptive parents. Hispanic children are more than twice as likely as African-American children to live in cohabiting-parent families and about four times as likely as Caucasian children to live in this kind of family arrangement (Wherry & Finegold, 2004).

Single-parent families comprise an unmarried biologic or adoptive parent who may or may not be living with other adults. The single-parent family may result from the loss of a spouse by death, divorce, separation, or desertion; from either an unplanned or planned pregnancy; or from the adoption of a child by an unmarried woman or man. This family structure is continually on the rise. In 2007 according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.6 million single parents lived in the United States. These 13.6 million single parents are raising 26% of the children in the United States younger than age 18 (Wolf, 2008). The single-parent family tends to be vulnerable economically and socially, creating an unstable and deprived environment for the growth of children. Research demonstrates the effect of single parenthood not only in economic instability but also in relation to health status, school achievement, and high risk behaviors for these children. Single mothers are more likely to live in poverty and have poor perinatal outcomes (Schor, 2003; Spencer, 2005; Weitoft, Hjern ,Haglund, & Rosen, 2003).

Another family configuration that is less well documented is the increasing number of homosexual families (lesbian and gay), who may live together with or without children. It is estimated that between 800,000 and 7 million homosexual parents are raising between 1 and 9 million children (Cameron, 2004). Although there is no consensus as to what constitutes a gay and lesbian family, these families are rich and diverse in their form and composition. Usually formed by same-sex couples, they can also consist of single gay or lesbian parents or multiple parenting figures.

Children in lesbian and gay families may be the offspring of previous heterosexual unions, conceived by one member of a lesbian couple through therapeutic insemination, or adopted. These trends reflect the increased opportunities for alternative forms of parenthood within our society, owing both to more liberal social mores and to technologic and medical advances that offer the possibility of parenthood to single men and women (Greenfeld, 2005).

No-parent families are those in which children live independently in foster or kinship care such as living with a grandparent. An estimated 6.6 million children in the U.S. have grandparents living in their home. Of these grandparents, 23% are primary caretakers for their grandchildren; nearly half of these have assumed this responsibility for more than 5 years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009a).

The Family in Society

The social context for the family can be viewed in relation to social and demographic trends that define the population as a whole. U.S. census data indicate that the racial and ethnic diversity of the population has grown dramatically in the past three decades; 30% of all U.S. citizens belong to racial or ethnic minority groups (USDHHS, 2010). Statistics reflect a population that is 79.8% Caucasian, 15.4% Hispanic, 12.8% African-American, 4.5% Asian-American, and Native American or Pacific Islander (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009b). According to these statistics, the Hispanic population continues to comprise the largest minority group in the United States.

Theoretic Approaches to Understanding Families

Family plays a pivotal role in health care, representing the primary target of health care delivery for maternal and newborn nurses. It is crucial that nurses assist families as they incorporate new additions to their family (see Nursing Care Plan). The core concepts of woman- and family-centered care are dignity and respect, information sharing, participation, and collaboration (Johnson, Abraham, Conway, Simmons, Edgman-Levitan, Sodomka, et al., 2008). When treating the woman and family with respect and dignity, health care providers listen to and honor perspectives and choices of the woman and family. They share information with families in ways that are positive, useful, timely, complete, and accurate. The family is supported in participating in the care and decision making at the level of their choice.

Family Assessment

When selecting a family assessment framework, an appropriate model for a perinatal nurse is one that is a health-promoting rather than an illness-care model. The low risk family can be assisted in promoting a healthy pregnancy, childbirth, and integration of the newborn into the family. The high risk perinatal family has illness-care needs, and the nurse can help to meet those needs while also promoting the health of the childbearing family.

Family Theories

A family theory can be used to describe families and how the family unit responds to events both within and outside the family. Each family theory makes certain assumptions about the family and has inherent strengths and limitations. Most nurses use a combination of theories in their work with families. A brief synopsis of several theories useful in working with families is included in Table 2-1. Application of these concepts can guide assessment and interventions for the family.

TABLE 2-1

THEORIES AND MODELS RELEVANT TO FAMILY NURSING PRACTICE

| THEORY | SYNOPSIS OF THEORY |

| Family Systems Theory (Wright & Leahy, 2005) | The family is viewed as a unit, and interactions among family members are studied rather than studying individuals. A family system is part of a larger suprasystem and is composed of many subsystems. The family as a whole is greater than the sum of its individual members. A change in one family member affects all family members. The family is able to create a balance between change and stability. Family members’ behaviors are best understood from a view of circular rather than linear causality. |

| Family Life Cycle (Developmental) Theory (Carter & McGoldrick, 1999) | Families move through stages. The family life cycle is the context in which to examine the identity and development of the individual. Relationships among family members go through transitions. Although families have roles and functions, a family’s main value is in relationships that are irreplaceable. The family involves different structures and cultures organized in various ways. Developmental stresses may disrupt the life cycle process. |

| Family Stress Theory (Boss, 1996) | How families react to stressful events is the focus. Family stress can be studied within the internal and external contexts in which the family is living. The internal context involves elements that a family can change or control, such as family structure, psychologic defenses, and philosophic values and beliefs. The external context consists of the time and place in which a particular family finds itself and over which the family has no control, such as the culture of the larger society, the time in history, the economic state of society, maturity of the individuals involved, success of the family in coping with stressors, and genetic inheritance. |

| McGill Model of Nursing (Allen, 1997) | Strength-based approach in clinical practice with families, as opposed to a deficit approach, is the focus. Identification of family strengths and resources; provision of feedback about strengths; assistance given to family to develop and elicit strengths and use resources are key interventions. |

| Health Belief Model (Becker, 1974; Janz & Becker, 1984) | The goal of the model is to reduce cultural and environmental barriers that interfere with access to health care. Key elements of the Health Belief Model include the following: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and confidence. |

| Human Developmental Ecology (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; 1989) | Behavior is a function of interaction of traits and abilities with the environment. Major concepts include ecosystem, niches (social roles), adaptive range, and ontogenetic development. Individuals are “embedded in a microsystem [role and relations], a mesosystem [interrelations between two or more settings], an exosystem [external settings that do not include the person], and a macrosystem [culture]” (Klein & White, 1996). Change over time is incorporated in the chronosystem. |

Because so many variables affect ways of relating, the nurse must be aware that most family members will interact and communicate with each other in ways that are very different from

those of the nurse’s own family of origin. Most families will hold at least some beliefs about health that are very different from those of the nurse. Their beliefs can conflict with principles of health care management predominant in the Western health care system.

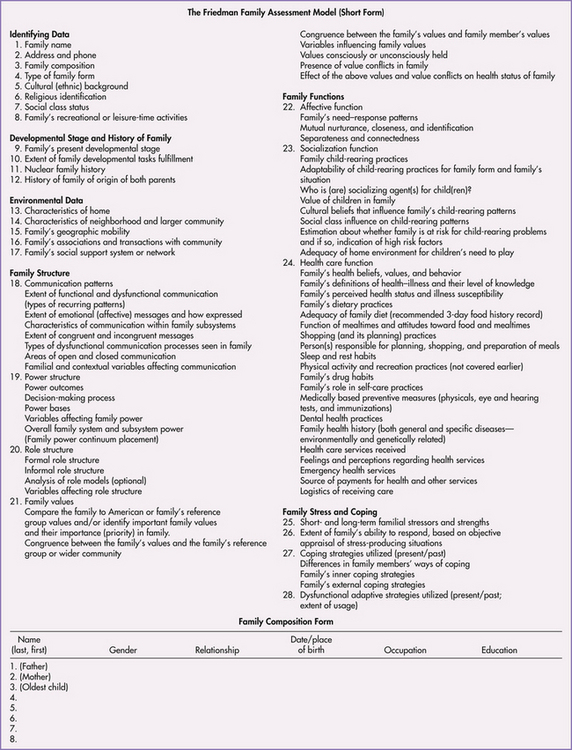

A family assessment tool such as the one outlined by Friedman (1998) (Fig. 2-3) can be used as a guide for assessing aspects of the family.

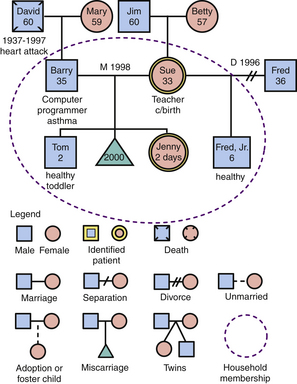

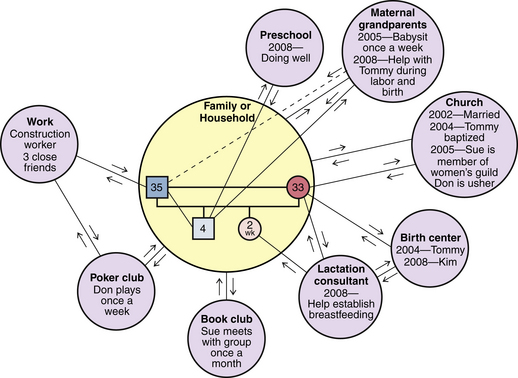

Graphic Representations of Families

A family genogram (family tree format depicting relationships of family members over at least three generations) (Fig. 2-4) provides valuable information about a family and can be placed in the nursing care plan for easy access by care providers. An ecomap, a graphic portrayal of social relationships of the women and family, may also help the nurse understand the social environment of the family and identify support systems available to them (Fig. 2-5) (Rempel, Neufeld, & Kushner, 2007). Software is available to generate genograms and ecomaps (www.interpersonaluniverse.net).

The Family in a Cultural Context

Cultural Factors Related to Family Health

Cultural knowledge includes beliefs and values about each facet of life and is passed from one generation to the next. Cultural beliefs and traditions relate to food, language, religion, art, health and healing practices, kinship relationships, and all other aspects of community, family, and individual life. Culture has also been shown to have a direct effect on health behaviors. Values, attitudes, and beliefs that are culturally acquired may influence perceptions of illness, as well as health care–seeking behavior and response to treatment. The political, social, and economic context of people’s lives is also part of the cultural experience.

Culture, shared beliefs and values of a group, plays a powerful role in an individual’s behavior, particularly when the individual is sick. Understanding a culture can provide insight into how a person reacts to illness, pain, and invasive medical procedures, as well as patterns of human interaction and expressions of emotion. The effect of these influences must be assessed by health professionals in providing health care and developing effective intervention strategies. Culture is not static; it is an ongoing process that influences a woman throughout her entire life, from birth to death. Culture is an essential element of what defines us as people.

Many subcultures may be found within each culture. Subculture refers to a group existing within a larger cultural system that retains its own characteristics. A subculture may be an ethnic group or a group organized in other ways. For example, in the United States and Canada, many ethnic subcultures such as African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and Native Americans exist. It is important to note that subcultures also exist within these groups. In addition, the Caucasian population in America has multiple subcultures of its own. Because every identified cultural group has subcultures and because it is impossible to study every subculture in depth, greater differences may exist among and between groups than is generally acknowledged. It is important to be familiar with common cultural practices within these subgroups. However, it is also important to avoid the generalization that every person practices every cultural belief within a group.

In a multicultural society, many groups can influence traditions and practices. As cultural groups come into contact with each other, acculturation and assimilation may occur.

Acculturation refers to the changes in one’s cultural pattern to those of the host society (Spector, 2008). These changes take place within one group or among several groups when people from different cultures come into contact with one another. People may retain parts of their own culture while adopting cultural practices of the dominant society. This familiarization among cultural groups results in overt behavioral similarity, especially in mannerisms and dress. Language patterns, food choices, and health practices are often much slower to adapt to the influence of acculturation. Furthermore, during times of family transitions such as childbearing, or during crisis or illness, a person may rely on old cultural patterns even after becoming acculturated in many ways. This is consistent with the family developmental theory that states that during times of stress, people revert to practices and behaviors that are most comfortable and familiar.

Assimilation means becoming in all ways like the members of the dominant culture (Spector, 2008). This process involves the complete loss of cultural identity while acquiring a new cultural identity. Assimilation is the process by which groups “melt” into the mainstream, thus accounting for the notion of a “melting pot,” a phenomenon that has been said to occur in the United States. This is illustrated by individuals who identify themselves as being of Irish or German descent, without having any remaining cultural practices or values linked specifically to that culture such as food preparation techniques, style of dress, or proficiency in the language associated with their reported cultural heritage. Spector asserts that in the United States the melting pot, with its dream of a common culture, is a myth. Instead, a mosaic phenomenon exists in which we must accept and appreciate the differences among people.

Implications for Nursing

As our society becomes more multiculturally diverse, it is essential that nurses become culturally competent. It is crucial for nurses to be familiar with their own beliefs so that they have a better appreciation and understanding of the beliefs of their clients (see Clinical Reasoning box). Understanding the concepts of ethnocentrism and cultural relativism may help nurses care for families in a multicultural society.

Ethnocentrism refers to the view that one’s own culture’s way of doing things is best (Giger & Davidhizar, 2009). Although the United States is a culturally diverse nation, the prevailing practice of health care is based on the beliefs and practices held by members of the dominant culture, primarily Caucasians of European descent. This practice is based on the biomedical model that focuses on curing disease states. From this biomedical perspective, pregnancy and childbirth are viewed as processes with inherent risks that are most appropriately managed by using scientific knowledge and advanced technology.

The medical perspective stands in direct contrast with the belief systems of many cultures. Among many women, birth is traditionally viewed as a completely normal process that can be managed with a minimum of involvement from health practitioners. When encountering behavior in women unfamiliar with the biomedical model, the nurse may become frustrated and impatient. The nurse may label the women’s behavior inappropriate and believe that it conflicts with “good” health practices. If the Western health care system provides the nurse’s only standard for judgment, the behavior of the nurse is called ethnocentric.

Cultural relativism is the opposite of ethnocentrism. It refers to learning about and applying the standards of another’s culture to activities within that culture. The nurse recognizes that people from different cultural backgrounds comprehend the same objects and situations differently. In other words, culture determines viewpoint.

Cultural relativism does not require nurses to accept the beliefs and values of another culture. Instead, they recognize that the behavior of others may be based on a system of logic different from their own. Cultural relativism affirms the uniqueness and value of every culture.

Childbearing Beliefs and Practices

Nurses working with childbearing families care for families from many different cultures and ethnic groups. To provide culturally competent care, the nurse should be aware of the spectrum of cultural beliefs and practices important to individual families. When working with childbearing families, a nurse should consider all aspects of culture including communication, space, time orientation, and family roles.

Communication often creates the most challenging obstacle for nurses working with clients from diverse cultural groups. This is because communication is not merely the exchange of words. Instead it involves (1) understanding the individual’s language, including subtle variations in meaning and distinctive dialects; (2) appreciation of individual differences in interpersonal style; and (3) accurate interpretation of the volume of speech as well as the meanings of touch and gestures. For example, members of some cultural groups tend to speak more loudly when they are excited, with great emotion and with vigorous and animated gestures; this is true whether their excitement is related to positive or negative events or emotions. It is important, therefore, for the nurse to avoid rushing to judgment regarding a client’s intent when the client is speaking, especially in a language not understood by the nurse. Instead, the nurse should withhold an interpretation of what has been expressed until it is possible to clarify the client’s intent. The nurse must quickly enlist the assistance of a person who can help, and seek to verify with the client the true intent and meaning of the communication.

Inconsistencies between the language of clients and the language of providers present a significant barrier to effective health care. For example, there are many dialects of Spanish that vary by geographic location. Because of the diversity of cultures and languages within the U.S. and Canadian populations, health care agencies are increasingly seeking the services of interpreters (of oral communication from one language to another) or translators (of written words from one language to another) to bridge these gaps and fulfill their obligation for culturally and linguistically appropriate health care (Box 2-1). Finding the best possible interpreter in the circumstance is critically important as well. However, ideal interpretive services sometimes are impossible to find when they are needed because the nature of nursing care is not always predictable and because nursing care that is provided in a home or community setting does not always allow expert, experienced, or mature adult interpreters. The ideal interpreter has had training in health care interpretation so that she or he can help promote effective communication. Health care providers are encouraged to use these individuals when communicating with non–English-speaking clients in order to effectively communicate and to prevent possible liability from misinterpretation. However, in crisis or emergency situations, or when family members are having extreme stress or emotional upset, it may be necessary to use relatives, neighbors, or children as interpreters. If this occurs, the nurse must ensure that the client is in agreement and comfortable with using the available interpreter to assist.

When using an interpreter, the nurse respects the family by creating an atmosphere of consideration and privacy. Questions should be addressed to the woman and not to the interpreter. Even though an interpreter will of necessity be exposed to sensitive and privileged information about the family, the nurse should take care to ensure that confidentiality is maintained. A quiet location free from interruptions is ideal for interpretive services to take place. It is also appropriate to use written literature, videos, or other material to help with the woman’s understanding of information that is presented. It is important to ensure that the material has been translated by someone who is trained appropriately, to avoid liability issues.

Personal Space

Cultural traditions define the appropriate personal space for various social interactions. Although the need for personal space varies from person to person and with the situation, the actual physical dimensions of comfort zones differ from culture to culture. Actions such as touching, placing the woman in proximity to others, taking away personal possessions, and making decisions for the woman can decrease personal security and heighten anxiety. Conversely, if nurses respect the need for distance, they allow the woman to maintain control over personal space and support the woman’s autonomy, thereby increasing her sense of security. For example, many Asian groups have reserved attitudes about physical contact, and this may at times create anxiety when health care is delivered.

Nurses often use touch, and frequently do so without any awareness of the emotional distress they may be causing to clients. In the home care setting, a nurse who must provide physical care to a woman with a disease may cause the woman great anxiety because she fears that her disease will be spread to the nurse. Fears about spreading the disease also may interfere with her acceptance of physical comfort and care from family members.

Time Orientation

Time orientation also is a fundamental way in which culture affects health behaviors. People in cultural groups may be relatively more oriented to past, present, or future. Those who focus on the past strive to maintain tradition or the status quo and have little motivation for formulating future goals. In contrast, individuals who focus primarily on the present neither plan for the future nor consider the experiences of the past. These individuals do not necessarily adhere to strict schedules and are often described as “living for the moment,” or “marching to their own drummer.” Individuals oriented to the future maintain a focus on achieving long-term goals.

The time orientation of the childbearing family may affect nursing care. For example, talking to a family about bringing the infant to the clinic for follow-up examinations (events in the future) may be difficult for the family that is focused on the present concerns of day-to-day survival. Because a family with a future-oriented sense of time plans far in advance, thinking about the long-term consequences of present actions, they may be more likely to return as scheduled for follow-up visits. Despite the differences in time orientation, each family can be equally concerned for the well-being of its newborn.

Family Roles

Family roles involve the expectations and behaviors associated with a member’s position in the larger family system (e.g., mother, father, or grandparent). Social class and cultural norms also affect these roles, with distinct expectations for men and women clearly determined by social norms. For example, culture may influence whether a man actively participates in the pregnancy and childbirth, yet maternity care practitioners working in the Western health care system expect fathers to be involved. This can create a significant conflict between the nurse and the role expectations of very traditional Mexican or Arab families, who usually view the birthing experience as a female affair (see Cultural Considerations box). The way that health care practitioners manage such a family’s care molds its experience and perception of the Western health care system.

In maternity nursing and women’s health care, the nurse supports and nurtures the beliefs that promote physical or emotional adaptation to childbearing. However, if certain beliefs might be harmful, the nurse should carefully explore them with the woman and use them in the reeducation and modification process. Strategies for care delivery and providing appropriate care are presented in Box 2-2.

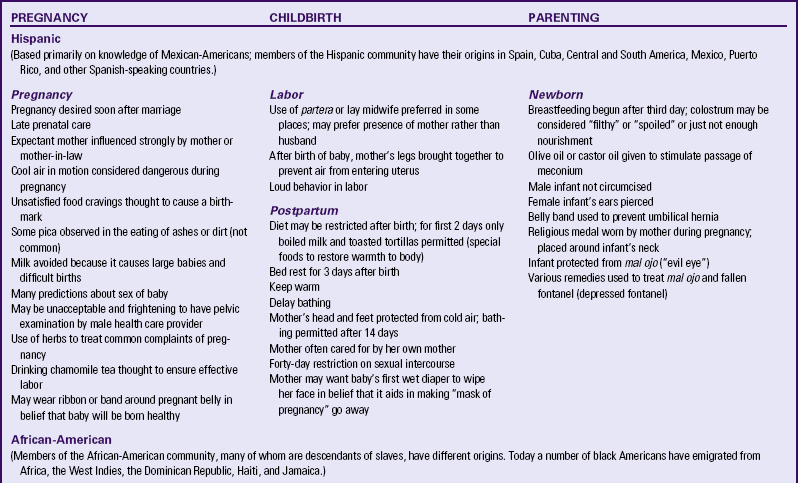

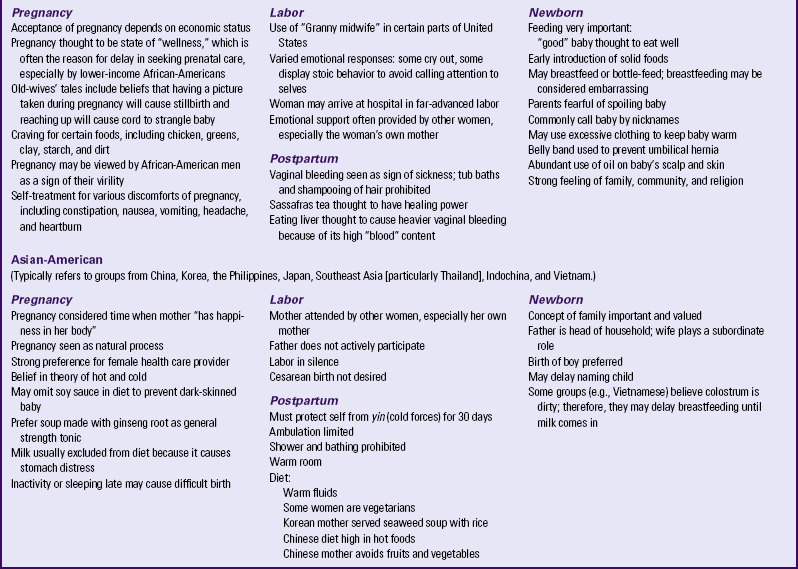

Few families are exclusively “Asian” or “Caucasian.” Instead they are often blended composites, with one partner bringing to the relationship the traditions of one culture or family of origin and the other partner bringing a slightly differing perspective. Even when partners are both of Asian ancestry, for example, their families of origin may come from different regions of the same country and follow completely different health practices. Table 2-2 provides examples of cultural beliefs and childbearing practices frequently encountered by the nurse who works

with women who identify themselves as European-American (Caucasian), Hispanic-American, Asian-American, African-American (black), or Native American. The cultural beliefs and customs in Table 2-2 are categorized based on distinct cultural traditions and are not practiced by all members of the cultural group in every part of the country. Women from these cultural and ethnic groups may adhere to a few, all, or none of the practices listed. In using this table as a guide, the nurse should use caution to avoid making stereotypic assumptions about any person based on sociocultural-spiritual affiliations. Nurses should exercise sensitivity in working with every family, being careful to assess the ways in which they apply their own mixture of cultural traditions.

Developing Cultural Competence

In today’s society, with its ever-expanding diversity, it is of critical importance that nurses develop more than technical skills. They need to develop cultural competence. There are as many varying definitions of cultural competence as there are for culture. According to Purnell and Paulanka (2008), cultural competence involves respecting the differences in others, including ethnicity, ethnoculture, and religious beliefs.

Key components of culturally competent care include:

• Recognizing that there is disparity between one’s own culture and that of the client

• Educating and promoting healthy behaviors in a cultural context that has meaning for clients

• Taking abstract knowledge about other cultures and applying it in a practical way, so that the quality of service improves and policies are enacted that meet the needs of all clients

• Communicating respectfulness for a wide range of differences, including client use of nontraditional healing practices and alternative therapies

• Recognizing the importance of culturally different communication styles, problem-solving techniques, concepts of space and time, and desires to be involved with care decisions

• Anticipating the need to address varying degrees of language ability and literacy, as well as barriers to care and compliance with treatment

Cultural competence affirms the uniqueness and value of every culture in nursing practice (www.bphc.hrsa.gov/cultural competence). For almost two decades, the American Academy of Nursing (1992) has pledged to promote transcultural nursing and to foster nursing expertise in culturally competent care, defined as a complex integration of knowledge, attitudes, and skills that enhance cross-cultural communications and lead to appropriate and effective interaction with others. It has always been vital that nurses develop the ability to relate to others, but the challenges of meeting the broad scope of these needs have never been greater.

Nurses must be continually involved in the development of cultural competence because it is of equal importance in terms of health outcomes as preserving and promoting human dignity. Nurses who relate effectively with clients are able to motivate them in the direction of health-promoting behaviors. Provider competence to address language barriers facilitates appropriate tailoring of health messages and preventive health teaching. Cross-cultural experiences also present an opportunity for the health care professional to expand cultural sensitivity, awareness, and skills.

Community Health Promotion

Best practices in community-based health initiatives involve understanding of community relationships and resources as well as participation of community leaders. The emphasis on community-based health promotion has grown in recent years, with recognition that many health issues require the collaborative efforts of a diverse community network to achieve public health goals (Cottrell, Girvan, & McKenzie, 2006). These efforts are particularly relevant in relation to maternal-newborn health, which is affected by multiple public health issues: lack of health insurance, recent economic challenges that include job loss, teen pregnancy, substance abuse, and the consequences of no or inadequate prenatal care.

Levels of Preventive Care

In community-based health promotion, there are three levels of prevention of disease. Primary prevention involves promoting healthy lifestyles through immunizations, encouraging exercise, and healthy nutrition. Secondary prevention involves targeting populations at risk for certain diseases. For example, women are encouraged to have mammograms; men are encouraged to have prostate screening. Tertiary prevention focuses on rehabilitation of an individual who already has a disease back to as optimal health as possible. For example, a person who has experienced a stroke has an optimal expectation of being able to function at his or her fullest potential. As nurses, we do what we can to ensure that this occurs.

During pregnancy, primarily primary and secondary prevention are relevant. The goal is to maintain a healthy pregnancy by preventing illness and screening those at risk for potential illnesses or complications that could arise during pregnancy. In pregnancy, primary prevention might involve providing the influenza vaccine to women, whereas secondary prevention might involve performing an amniocentesis for a woman older than age 35.

Promoting Family Health

Functioning within the social, cultural, environmental, and economic context of the community, the family becomes an integral component of community health promotion efforts (Friedman, Bowden, & Jones, 2003). For childbearing families, health promotion is primarily focused on early intervention through prenatal care and prevention of complications during the perinatal period. Often this early exposure to health information sets the stage for a successful birth and positive outcomes for mother and baby. Family systems and developmental theories provide a framework for the appropriate timing and content of health promotion activities. The nurse’s role in this process is focused on collaboration with the family, identifying risk factors, and providing health information to facilitate positive health behaviors. Involving expectant mothers and fathers in identification of their learning needs is an essential first step to securing their participation in the health promotion process.

A wide variety of strategies have been used to engage families and groups in health-promoting activities or community health programs. Some are more successful than others. Generally, participant engagement in the planning process and empowerment to create internal solutions are considered key factors in effective interventions. Many communities have organized coalitions to address specific health promotion agendas related to sharing information, educating community members, or advocating for health policies around maternal and child health issues. An example of this is the National Friendly Access Program (2003), a community-based initiative to improve access to maternal and child care by changing provider behaviors. The benefits of partnership with faith-based organizations for community health improvement have been demonstrated in health promotion efforts aimed at lifestyle choices, health education, and maternal-child health outcomes. Another community-based partnership demonstrated the potential for policy and practice improvements in maternal-child health systems around the issues of provider access, transportation, and discrimination in health care practices (Pincus, Thomas, Keyser, Castle, Dembosky, Firth, et al., 2003).

Prepared childbirth classes are a well-established mechanism for increasing awareness of healthy behaviors during pregnancy and preparing parents for the care of themselves and their newborn during the postpartum period. Mass media efforts such as those presented by the March of Dimes “Baby Your Baby” advertisements are clear consumer-friendly messages designed to reach a large target audience. Other venues include public health education in newspapers and magazines, and health department programs such as the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which offers a variety of health education and written information to mothers.

Assessing the Community

A community assessment is a tool that is used to assess the health and well-being of a community. One can define “community” either geographically or as having a common characteristic. For example, one can do a community assessment of clients who live in a particular neighborhood or of women who have developed preterm labor. In doing the community assessment, risk factors for certain diseases, patterns of illness, cultural beliefs, religious beliefs, transportation systems, and support systems are just a few factors that are assessed in order to determine how these components relate to certain patterns of illness.

In a community health assessment data are collected, analyzed, and used to educate and mobilize communities, develop priorities, garner resources, and plan actions to improve public health. Many models and frameworks of community assessment are available, but the actual process often depends on the extent and nature of the assessment to be performed, the time and resources available, and the way the information is to be used (www.assessnow.info/resources/models-of-community-health-assessment).

Data Collection and Sources of Community Health Data

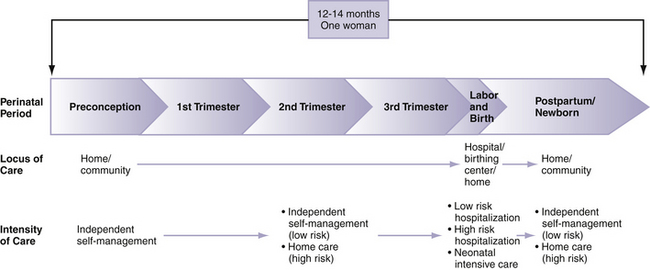

Important measures of community health include, for example, access to care, level of provider services available, availability of transportation, and family support. Consideration of a variety of these factors helps one to assess areas that may affect care so that nurses can introduce alternatives to meet the needs of clients. For example, if a client has to work Monday through Friday, from 8 am to 5 pm, the nurse can facilitate an after-hours appointment. A community assessment model (Fig. 2-6) can be used to provide a comprehensive guide to data collection.

FIG. 2-6 Community health assessment wheel. (From Clemen-Stone, S. (2002). In S. Clemen-Stone, S. McGuire, & D. Eigsti. [2002]. Comprehensive community health nursing: Family, aggregate, & community practice [6th ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.

The most critical community indicators of perinatal health relate to access to care; maternal mortality; infant mortality; low birth weight; first trimester prenatal care; and rates for mammography, Papanicolaou smears, and other similar screening tests (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2005). Nurses can use these indicators as a reflection of access, quality, and continuity of health care in a community. For women and infants, access to a consistent source of care is critical. Those with a regular source of care are more likely to use preventive services and have more positive pregnancy outcomes, but current statistics indicate that many women lack access to a usual source of care or rely primarily on emergency services.

Access to health care relates not only to the availability of health department services, hospitals, public clinics, clinic hours, or other sources of care, but also to accessibility of care. In many areas where facilities and providers are available, geographic and transportation barriers render the care inaccessible for certain populations. This is particularly true in rural areas or other remote locations that lack such resources as public health departments, public transportation, and other necessary prenatal services. Other barriers to care should also be evaluated including cultural and language barriers, and lack of providers or specialty care.

Some local health departments, due to lack of funding, are not able to provide all services to meet the needs of the communities they serve. For example, health departments may not offer prenatal clinics for pregnant clients, and primary care and adult health clinics are unavailable. Although this can be a result of a lack of financial resources, other contributing factors include a lack of health care providers to staff clinics. Although one growing trend to help provide increased access to care is retail health clinics in pharmacies and retail stores, they often do not provide care to pregnant women.

Health departments at the city, county, and state level are a valuable resource for annual reports of births and deaths. Local health departments also compile extensive statistics about the birth complications, causes of death, and leading causes of morbidity and mortality for each age-group. Local and state health data are compiled and reported through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (www.cdc.gov) to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The National Health Survey published annually from this source describes national health trends. However, national data are only as accurate and reliable as the local data on which they are based, so caution is needed in interpreting the data and applying it to specific population groups.

The U.S. census provides data on population size, age ranges, sex, racial and ethnic distribution, socioeconomic status, educational level, employment, and housing characteristics. Summary data are available for most large metropolitan areas, arranged by zip code and census tract, which usually corresponds to a neighborhood comprising approximately 3000 to 6000 people. Looking at individual census tracts within a community helps to identify subpopulations or aggregates whose needs may differ from those of the larger community. For example, women at high risk for inadequate prenatal care according to age, race, and ethnic or cultural group can be readily identified, and outreach activities can be appropriately targeted.

Other sources of useful information are hospitals and voluntary health agencies. The March of Dimes Foundation, for example, has supported perinatal needs assessments in many communities across the United States (www.modimes.org). Other community health resources include health care providers or administrators, government officials, religious leaders, and representatives of voluntary health agencies. Community or county health councils exist in many areas, with oversight of specific health initiatives or programs for that region. These key informants often provide a unique perspective that may not be accessible through other sources. Community gatekeepers who address the social and health care needs of the population are also critical links to population-specific health information.

The perinatal health nurse can explore existing community health program reports, records of preventive health screenings, and other informal data. Established programs often provide good indicators of the health promotion and disease prevention characteristics of the population.

Professional publications are a rich and readily accessible source of information for all nurses. In addition to nursing and public health journals, behavioral and social science literature offers diverse perspectives on community health status for specific populations and subgroups. The Internet has increased the availability and accessibility of national, state, and local health data as well. However, the use of Internet-based resources for health information requires caution because data reliability and validity are difficult to verify. (Guidelines for evaluation of Internet health resources can be found on the Health on the Net website, www.hon.ch).

Data collection methods may be either qualitative or quantitative and may include visual surveys that can be completed by walking through a community, participant observation, interviews, focus groups, and analysis of existing data. Potential clients and health care consumers may be asked to participate in focus groups or community forums to present their views on needed community services and programs. Formal surveys, conducted by mail, telephone, or face-to-face interviews, can be a valuable source of information not available from national databases or other secondary sources. Several drawbacks exist with this method: surveys are generally expensive to develop and time-consuming to administer. In addition to the cost of such surveys, poor response rates often preclude a sufficiently representative response on which to base nursing interventions.

A walking survey is generally conducted by a walk-through observation of the community (Box 2-3), taking note of specific characteristics of the population, economic and social environment, transportation, health care services, and other resources. With this type of data collection, information is gathered based on what the data collector observes, and is clearly objective data. Participant observation is another useful assessment method in which the nurse actively participates in the community to understand the community more fully and to validate observations (Stanhope & Lancaster, 2008).

Finally, as part of the assessment process, nurses working in multiethnic and multicultural groups need an in-depth assessment of culturally based health behaviors.

Analysis and synthesis of data obtained during the assessment process help to generate a comprehensive picture of the community’s health status, needs, and problem areas, as well as its strengths and resources for addressing these concerns. The goal of this process is to assign priorities to community health needs and to develop a plan of action for correcting them. A comparison of community health data with state and national statistics can be useful in identification of appropriate target populations as well as interventions to improve health outcomes.

Vulnerable Populations in the Community

Assessment of population health includes indicators related to diverse groups and cultures, particularly disenfranchised or “vulnerable” community members (www.crosshealth.com). Vulnerability in terms of health status and health outcomes may take many forms—including sociocultural, economic, and environmental risk factors that contribute to disparities in health. Health disparities are conditions that disproportionately affect certain racial, ethnic, or other groups. African-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Asian-Americans are all considered vulnerable populations because they are more likely to have poor health and die prematurely (CDC, 2007).

The Institute of Medicine report, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (2002), provides evidence of racial and ethnic disparities for a number of health conditions and services. According to the National Healthcare Disparities Report (AHRQ, 2008), disparities are pervasive and improvement is possible, but there are still gaps in information for many groups. Although health disparities have been evident across all domains of health care for several decades, the etiology of these differences is still unclear (Jacobs, Karavolos, Rathouz, Ferris, & Powell, 2005). Poverty, poor access to care, lack of preventive services, and inadequate health knowledge and skills all contribute to excess disease burden.

Women

Women comprise 51% of the U.S. population, representing a very diverse, and largely at risk, group in relation to health (USDHHS, 2009c). Although women assume leadership for health care decision making in most families, they also face significant challenges in accessing the health care system and meeting their own health needs and those of family members (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009). What is the source of women’s vulnerability? Although there is no single contributing factor, the primary sources of health disparities for women fall into the areas of gender, socioeconomic status, and race or ethnicity. Significant gaps exist in the quality of care for women when compared with men.

The National Report Card on Women’s Health describes significant deficiencies in women’s health (National Women’s Law Center [NWLC], 2007). States’ performance in relation to 27 key areas was assessed; most were rated as unsatisfactory in relation to women’s health status and policies influencing women’s health. Key indicators focused on access to services, use of preventive health care and health promotion activities, the occurrence of certain health conditions, and an assessment of the community’s effect on women’s health. This report suggested that one of the primary factors compromising women’s health is lack of access to acceptable-quality health care, which may manifest itself in many forms: lack of health insurance, living in a medically underserved area, or an inability to obtain needed services, particularly basic services such as prenatal care. Federal and state policies and programs also fail to safeguard women’s interests in relation to reproductive health and health care coverage (NWLC).

Although many women report that they are in good to excellent health, statistics reveal significant disparities in health status of women from all age-groups and racial and ethnic backgrounds (USDHHS, 2009c). Low levels of educational attainment (high school or lower) are also associated with lack of resources, and difficulty navigating the health care system. This is particularly true of women of ethnic and racial minorities, whose limited English proficiency may compromise provider access and quality of care (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009). According to recent statistics, 7 out of 10 working women lack health insurance coverage, which equates to 64 million American women (United Press International, 2009). Within this large group of women are those who are in the perinatal period, in which care, or the lack thereof, affects at least two individuals.

Racial and Ethnic Minorities

In addition to social, economic, and cultural barriers to optimal health, women who are in racial and ethnic minorities (29.3% of all U.S. women), experience a disproportionate burden of disease, disability, and premature death. Whereas 63% of non-Hispanic white females reported that they are in excellent or good health, only 53% of Hispanic and 51% of non-Hispanic black women reported this level of health (CDC, 2009a).

Significant health disparities continue to exist in adult women’s health and the health of their infants. Although positive trends are evident, there are persistent disparities among racial and ethnic groups in early prenatal care, an important factor in achieving healthy pregnancy outcomes (CDC, 2009a). The goals of Healthy People 2020 are reflective of the health disparities that exist among various populations, with emphasis on reduction of fetal and infant deaths, reduction of preterm births, reduction of maternal deaths, among others (USDHHS, 2009d) (see Box 1-2).

Minority women, many of whom live in poverty, also have higher rates of chronic disease including heart disease, cancer, hepatitis, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and mental health issues (USDHHS, 2009c). Women with underlying health conditions are at especially high risk for poor obstetric outcomes for themselves and their infants. They have high rates of preterm labor and gestational hypertension, and often have intrauterine growth restriction resulting in the birth of infants who are small for gestational age. These are the women for whom the community-based perinatal nurse will be providing care, and their needs are complex, demanding high levels of expertise and skill.

Adolescent Girls

The adolescent population in the United States is generally considered healthy. However, the adolescent population participates in riskier behaviors and their health is often compromised as a result. In 2006 13,739 deaths were reported among teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19, with unintentional injuries being the main cause of death, followed by homicide and suicide (USDHHS, 2009b).

Although adolescents are concerned about becoming pregnant, they still engage in unprotected sex. Adolescents also use a variety of sources for health information—the media, friends, and sex education—yet they are very misinformed, particularly about STIs and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission. These findings have significant implications for perinatal outcomes and emphasize the importance of aggressive prevention programs and community outreach related to sexuality, teen pregnancy, and substance abuse.

As the rate of adolescent pregnancy continues to rise and as STIs become more prevalent, it is crucial that nurses engage adolescents in health education programs that will encourage them to make informed decisions about their sexual health. It is also vital that nurses be a resource to these women.

Older Women

It is estimated that in the United States in 2008, 22.4 million women were older than age 65 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009b). Although women have a greater life expectancy than men, they are more likely to have chronic illnesses, less likely to use preventive services, and ultimately spend more on health care (CDC). As nurses, it is important that we engage this population at all levels of prevention, from primary to tertiary.

Incarcerated Women

The number of incarcerated women in the United States has continued to climb in recent years, increasing at a significantly greater rate than for men. In 2008, approximately 207,700 were in prison or jail, with the highest number of these being non-Hispanic black women (Department of Justice, 2009). Many of these women report a history of sexual and physical abuse.

Because their relationship histories are often unstable, and because they often lack the support of family, incarcerated women or those with a history of repeated incarceration frequently have difficulty providing emotional stability, secure housing, and health promotion role modeling for their children.

The lifestyle choices of this group, including risky sexual relationships, illicit drug use, and smoking, place them at high risk for STIs, HIV and AIDS, other chronic and communicable diseases, and complicated pregnancies.

Refugee and Migrant Women

As of 2006, one in every eight residents in the United States was foreign born, the highest number since 1920 (Martin, 2007). This accounts for a rapidly growing diverse population for which nurses will be providing care. California, Texas, New York, Florida, and Illinois are among the states with the highest growing immigrant population, respectively (Martin). An immigrant is an individual who moves from one country to another in an effort to take up legal residency, whereas a refugee is an individual who is forced to leave his or her home country, often in search of a safer and more stable living environment.

Both populations are often challenged with not being able to easily access health care because they are not U.S. citizens. These women often do not seek medical care for fear of deportation. Access to care is further limited by health care policies that restrict Medicaid eligibility for these groups (Kaiser Commission, 2003a). Mohanty and colleagues (2005) compared the health care costs of immigrants to those of U.S. citizens. Refuting the assumption that immigrants place an extra burden on the health care system, the study revealed that total health care expenditures for immigrant adults and children were significantly lower than those of U.S.-born citizens.

Migrant laborers and their families face many problems, including financial instability, child labor, poor housing, lack of education, language and cultural barriers, and limited access to health and social services. Poor dental health, diabetes, hypertension, malnutrition, tuberculosis, skin diseases, and parasitic infections are common health issues among migrant populations (Feldman, Vallejos, Quandt, Fleischer, Schulz, Verma, et al., 2009; Henning, Graybill, & George, 2008). Primary health care services are largely provided by a number of migrant health centers, of which there are more than 400 throughout the United States. In 2008, more than 834,000 seasonal and migrant farm workers and their families were served (USDHHS, n.d.). Routine prenatal care, as well as screening and treatment for hypertension and diabetes, are provided. Community health nurses frequently encounter the challenges of providing culturally and linguistically appropriate care while facing numerous health issues.

Numerous reproductive health issues exist for migrant women, including less consistent use of contraception and increased rates of STIs. Migrants are less likely to receive early prenatal care and have a greater incidence of inadequate weight gain during pregnancy than do other poor women.

Along with their profound resilience and determination, refugees and immigrants have brought rich diversity to the United States in several important dimensions including cultural heritage and customs, economic productivity, and enhanced national vitality. In general, refugees are more likely to live in poverty than are immigrants. Over time, measures of health and well-being actually decline for the immigrant population as they become part of American society. Many of the conditions or illnesses that they acquire contribute to the persistence of disparities in maternal and neonatal health outcomes for both immigrants and refugees.

Rural Versus Urban Community Settings

Approximately 17% of the U.S. population lives in a rural area, with 80% of the land area considered to be rural (USDA, 2009). Characteristically, rural residents are older, less educated, and generally in poorer health than their urban counterparts. Rural communities are disproportionately affected by poverty and poor access to health care services. Lack of insurance presents an additional factor for poor health in rural areas. Of the 41 million uninsured residents of the United States, 1 in 5 lives in rural communities. In some states, up to 70% of rural residents lack insurance or rely on Medicaid.

Rural women are especially vulnerable to financial and transportation barriers to health care. Although women in rural counties report only fair to poor health, they pay considerably more for their health care. In rural communities, women have less access to prenatal care, which contributes to higher rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes including higher rates of preterm birth, low birth weight, and infant mortality. The disproportionate distribution of poverty and of variations in race/ethnicity, age, education, and availability and access to medical resources may be the link to infant mortality in rural areas.

Homeless Women

Homelessness among women is an increasing social and health issue in the United States. Although exact numbers are unknown because of the difficulty in tracking individuals without a permanent address, it is estimated that more than 744,000 people were homeless in 2005. Women make up 65% of the homeless population and are increasingly affected by poverty, making homelessness more prevalent for families and children, particularly among rural populations (National Coalition for the Homeless [NCFH], 2009).

Health issues among the homeless are numerous and result primarily from a lack of preventive care and a lack of resources in general. Health problems including chronic illness, asthma, circulatory problems, and diabetes are rampant. Homeless women face many health issues, related to lifestyle factors and the vulnerability resulting from being homeless. In addition to extreme poverty, women are at increased risk for illness and injury; many have been victims of domestic abuse, assault, and rape (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2005).

Although little is known about pregnancy in this population, about 20% of women do become pregnant while homeless. Conversely, pregnancy and recent birth are highly correlated with becoming homeless (ACOG, 2005). In addition to risk factors related to inadequate nutrition, inadequate weight gain, anemia, bleeding problems, and preterm birth, homeless women face multiple barriers to prenatal care: transportation, distance, and wait times. Most women also underutilize available prenatal services (Bloom, Bednarzyk, Devitt, Renault, Teaman, & VanLoock, 2004). The unsafe environment and high risk lifestyles often result in adverse perinatal outcomes.

Low Literacy

Individuals and groups for whom English is a second language often lack the skills necessary to seek medical care and function adequately in the health care setting. Communication barriers may affect access to care, particularly in such areas as making appointments, applying for services, and obtaining transportation.

Health literacy involves a spectrum of abilities, ranging from reading an appointment slip to interpreting medication instructions. There is growing evidence of the effects of low health literacy on adult health status (Rosal, Goins, Carbone, & Cortes, 2004; www.hsph.harvard.edu/healthliteracy). Low health literacy may also be an independent contributor to a disproportionate disease burden among disadvantaged populations. Disparities in preventive care, early screening for cancer, and utilization of health care services, particularly among minority women, have also been linked to language barriers (Jacobs et al., 2005; www.prenataled.com/healthlit).

As the United States becomes increasingly multicultural, nurses will be required to interact with non–English-speaking groups or those with limited health literacy. Consequently, health literacy must be viewed as a component of culturally and linguistically competent care. These skills must be assessed routinely to recognize a problem and accommodate clients with limited literacy skills.

Implications for Nursing

Although the long-term consequences of contemporary immigration for American society are unclear, the successful incorporation of immigrant families depends on the resources, benefits, and policies that ensure their healthy development and successful social adjustment. Culturally competent health care and involvement of the immigrant community in health care programs are recommended strategies for improving the access to and effectiveness of health care for this population.

The use of camp volunteers has been effective in assisting families living in migrant worker camps to obtain prenatal, postpartum, and infant care. Working in partnership with health professionals such as nurses, lay camp aides have been used effectively for outreach and health education; however, more strategies are needed to link traditional practices with the formal health care system. Guidance and information about other health resources are available to health care providers through the National Migrant Resource Program and the Migrant Clinicians Network.

Nurses working with homeless women and families are challenged to treat them with dignity and respect to establish a therapeutic relationship. Case management is recommended to coordinate the services and disciplines that may be involved in meeting the complex needs of these families. Whenever possible, general screening and preventive health services must be provided when the woman seeks treatment because this may be the only opportunity to provide health information and intervention. Building on existing coping strategies and strengths, the health care provider helps the woman and her family to reconnect with a social support system. Nurses also have an important role in advocating for funding to support health services to the homeless and to improve access to preventive care for all homeless populations.

Home Care in the Community

Modern home care nursing has its foundation in public health nursing, which provided comprehensive care to sick and well clients in their own homes. Specialized maternity home care nursing services began in the 1980s when public health maternity nursing services were limited and services had not kept pace with the changing practices of high risk obstetrics and emerging technology. Lengthy antepartum hospitalizations for such conditions as preterm labor and gestational hypertension created nursing care challenges for staff members of inpatient units.

Many women expressed their concern for the negative effect of antepartum hospitalizations on the family. Although clinical indications showed that a new nursing care approach was needed, home health care did not become a viable alternative until third-party payers (i.e., public or private organizations or employer groups that pay for health care) pushed for cost containment in maternity services.

In the current health care system, home care is an important component of health care delivery along the perinatal continuum of care (Fig. 2-7). The growing demand for home care is based on several factors:

• Interest in family birthing alternatives

• New technologies that facilitate home-based assessments and treatments

As health care costs continue to rise, and because millions of American families lack health insurance, there is greater demand for innovative, cost-effective methods of health care delivery in the community. Large health care systems are developing clinically integrated health care delivery networks whose goals are: (1) improved coordination of care and care outcomes; (2) better communication among health care providers; (3) increased client, payer, and provider satisfaction; and (4) reduced cost. The integration of clinical services changes the focus of care to a continuum of services that are increasingly community based.

Communication and Technology Applications

As maternity care continues to consist of frequent and brief contacts with health care providers throughout the prenatal and postpartum periods, services that link maternity clients throughout the perinatal continuum of care have assumed increasing importance. These services include critical pathways, telephonic nursing assessments, discharge planning, specialized education programs, parent support groups, home visiting programs, nurse advice lines, and perinatal home care. Hospitals may provide cross-training for hospital-based nurses to make postpartum home visits or to staff outpatient centers for postpartum follow-up.

Telephonic nursing care through services such as warm lines, nurse advice lines, and telephonic nursing assessments is a valuable means of managing health care problems and bridging the gaps among acute, outpatient, and home care services. Providers are using the Internet to communicate with clients who have an Internet service provider (ISP). Nursing care that occurs by telephone is interactive and responsive to immediate health care questions about particular health care needs. Warm lines are telephone lines that are offered as a community service to provide new parents with support, encouragement, and basic parenting education. Nurse advice lines, or toll-free nurse consultation services, often are supported by third-party payers or health management organization/managed care organization (HMO/MCO) and are designed to provide answers to medical questions. Nurse care managers are prepared to guide callers through urgent health care situations, suggest treatment options, and provide health education. Telephonic nursing assessments, or nurse consultation, assessment, and health education that take place during a telephone conversation, can be added to the plan of care in conjunction with skilled nursing visits, or they may comprise a separate nursing contact for the woman. Telephonic nursing assessments are commonly used after a postpartum home care visit to reassess a woman’s knowledge about the signs and symptoms of adequate hydration in breastfeeding, or, after initiating home phototherapy, to assess the caregiver’s knowledge regarding problems with equipment.

Guidelines for Nursing Practice

The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN, 2009) defines home care as the provision of technical, psychologic, and other therapeutic support in the woman’s home rather than in an institution. The scope of nursing care delivered in the home is necessarily limited to practices deemed safe and appropriate to be carried out in an environment that is physically separated from a health care institution and its resources. Nursing practice at home is consistent with federal and state regulations that direct home care practice. The nurse demonstrates practice competence through formalized orientation and ongoing clinical education and performance evaluation in the respective home care agency. Standards for practice from key specialty organizations such as AWHONN, the ACOG, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Intravenous Nursing Society (INS) provide the basis for clinical protocols and pathways and organizational programs in home care practice. The Joint Commission (www.jointcommission.org) provides criteria for home care operations based on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations (cms.hhs.gov).

A wide range of professional health care services and products can be delivered or used in the home by means of technology and telecommunication. For example, telehealth and telemedicine make it possible for clients in the home to be interviewed and assessed by a specialist located hundreds of miles away. Home health care can be viewed as an extension of in-hospital care. Essentially, the primary difference between health care in a hospital and home care is the absence of the continuous presence of professional health care providers in a client’s home. Generally, but not always, home health care entails intermittent care by a professional who visits the client’s home for a particular reason and/or provides care onsite for fewer than 4 hours at a time. The home health care agency maintains on-call professional staff to assist home care clients who have questions about their care and for emergencies, such as equipment failure.

Perinatal Services

Home care perinatal services may be provided by hospital-based programs, independent proprietary (for-profit) agencies, or nonprofit home care agencies, and official or tax-supported agencies. Innovative programs may be supported by research grants for a period of years, but ultimately they must be sponsored by an agency with long-term funding. Home visits have advantages and disadvantages. The pregnant woman is able to maintain bed rest if indicated, and vulnerable neonates are not exposed to the weather or external sources of infection. The nurse can observe and interact with family members in their most natural and secure environment. Adequacy of resources and safety factors can be assessed. Teaching can be tailored to the actual home conditions, and other family members can be included. A home visit is less expensive than a day’s hospitalization, but a 60- to 90-minute visit requires 2.5 to 3 hours of nursing time, including travel and documentation. Areas of challenge include limited availability of nurses with expertise in maternity care and concerns about the nurse’s physical safety in the community. One alternative that is less expensive is contacting women via telephone.

Visits for outreach and health promotion are an integral part of community (or public) health nursing. In countries with national health systems, a nurse or midwife may see all women during pregnancy and after birth. In the United States, visits of this sort have been provided mainly to low-income families without health insurance and Medicaid recipients who use the clinics provided by local health departments. Until recently, private insurers did not reimburse for health promotion visits. MCOs now recognize that anticipatory guidance can be cost-effective, but home visitation programs for the most part still target specific, high risk populations, such as adolescents and women at risk for preterm labor.

Home care agencies are subject to regulation by governmental and professional organizations and provide interdisciplinary services including social work, nutrition, and occupational and physical therapy. Increasingly, their case loads are made up of women who require high-technology care, such as infusions or home monitoring. Although the home health nurse develops the care plan, all care must be ordered by a physician. In addition, interventions must meet the insurer’s criteria for reimbursement, and services are limited to registered clients. Preconception care and low risk antepartum care can usually be provided more efficiently in offices and are not currently reimbursable. High risk antepartum care can be provided by home care agencies; for example, women with hyperemesis gravidarum who require parenteral nutrition may be treated at home. Conditions requiring bed rest, such as preterm labor and hypertension, are other common indications for home care. Other conditions often managed with home care may include cardiac disease, substance abuse, and diabetes in pregnancy.

Insurers may reimburse for at least one postpartum visit to families after early discharge or in the presence of high risk factors. Home phototherapy is used for treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and to avoid separation of mother and infant. Many other neonates who require long-term high-technology care are also managed with home care.

Client Selection and Referral

The office or hospital-based nurse is often the key person in making effective referrals to home care. When considering a referral to home care, the following factors are evaluated:

• Health status of mother and fetus or infant: Is the condition serious enough to warrant home care, and is it stable enough for intermittent observation to be sufficient?

• Availability of professionals to provide the needed services within the woman’s community

• Family resources, including psychosocial, social, and economic resources: Will the family be able to provide care between nursing visits? Are relationships supportive? Is third-party reimbursement available, or can it be negotiated with the insurer? Could a voluntary or tax-supported community agency provide needed care without payment?

• Cost-effectiveness: Is it more reasonable for the woman to receive these services at home or to go to a local outpatient facility to receive them?

Community referrals should not be limited to women with physiologic complications of pregnancy that require medical treatment. Women at risk (e.g., young adolescents, families with a history of abuse, members of vulnerable population groups, developmentally disabled individuals) may need follow-up care at home. As we move more and more into an interdisciplinary health care society, it is crucial that nurses communicate with social workers to tap into valuable community resources that women can use once in their community.