21st Century Maternity and Women’s Health Nursing

• Describe the scope of maternity and women’s health nursing.

• Evaluate contemporary issues and trends in maternity and women’s health care.

• Examine social concerns in maternity nursing and women’s health care.

• Differentiate between standard (allopathic or Western) and holistic health care.

• Describe the scope of perinatal education in the community.

• Explain risk management and standards of practice in the delivery of nursing care.

Maternity nursing encompasses care of childbearing women and their families through all stages of pregnancy and childbirth, as well as the first 4 weeks after birth. Throughout the prenatal period, nurses, nurse practitioners, and nurse-midwives provide care for women in clinics and physicians’ offices and teach classes to help families prepare for childbirth. Nurses care for childbearing families during labor and birth in hospitals, in birthing centers, and in the home. Nurses with special training may provide intensive care for high risk neonates in special care units and for high risk mothers in antepartum units, in critical care obstetric units, or in the home. Maternity nurses teach about pregnancy; the process of labor, birth, and recovery; and parenting skills. They provide continuity of care throughout the childbearing cycle.

Women’s health care focuses on the physical, psychologic, and social needs of women throughout their lives. In the care of women, their overall experience is emphasized: general physical and psychologic well-being, childbearing functions, and diseases. Women’s health nurses specialize in and investigate conditions unique to women (such as reproductive malignancies and menopause) and sociocultural and occupational factors that are related to women’s health problems (such as poverty, rape, incest, and family violence). They also provide care for women and their families during the childbearing cycle.

Nurses caring for women have helped make the health care system more responsive to women’s needs. Nurses have been critically important in developing strategies to improve the well-being of women and their infants and have led the efforts to implement clinical practice guidelines and to practice using an evidence-based approach. Through professional associations, nurses can have a voice in setting standards and in influencing health policy by actively participating in the education of the public and of state and federal legislators. Some nurses hold elective office and influence policy directly. For example, in 2008 the American Nurses Association (ANA) published ANA’s Health System Reform Agenda, and in 2009 a nurse was appointed Administrator of the Health Resources and Services Administration, the agency that oversees approximately 7000 community clinics that serve low-income and uninsured people (Obama Chooses UND’s Mary Wakefield as Health Resources and Services Administration Leader, February 20, 2009).

Although tremendous advances have taken place in the care of mothers and their infants during the past 150 years (Box 1-1), serious problems exist in the United States related to the health and health care of mothers and infants. Lack of access to prepregnancy and pregnancy-related care for all women and the lack of reproductive health services for adolescents are major concerns. Sexually transmitted infections, including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), continue to affect reproduction adversely.

Racial and ethnic diversity is increasing within North America. It is estimated that by the year 2050, 50% of the population will be European-American, 15% will be African-American, 24% will be Hispanic, and 8% will be Asian-American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). Significant disparity exists in health outcomes among people of various racial and ethnic groups despite the great strides in public health made by the United States.

In addition, people may have lifestyles, health needs, and health care preferences related to their ethnic or cultural backgrounds. They may have dietary preferences and health practices that are not understood by caregivers. This presents a challenge for health care providers to provide culturally sensitive care. To meet the health care needs of a culturally diverse society, there must be increasing diversity of the nursing workforce.

This chapter presents a general overview of issues and trends related to the health and health care of women and infants.

Contemporary Issues and Trends

Healthy People provides science-based 10-year national objectives for improving health and preventing disease in the United States (www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020). In Healthy People 2010 the 467 objectives to improve health were organized into 28 specific focus areas, including one related to maternal, infant, and child health.

Healthy People 2020 has four recommended overarching goals: (1) eliminate preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death; (2) achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups; (3) create social and physical environments that promote good health for all; and (4) promote healthy development and healthy behaviors across every stage of life. The goals of Healthy People 2020 are based on assessments of major risks to health and wellness, changes in public health priorities, and issues related to the health preparedness and prevention of our nation. Objectives of Healthy People 2010 have been retained or revised and some new ones included (Box 1-2).

Millennium Development Goals

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are eight goals to be achieved by 2015 that respond to the world’s main development challenges. The MDGs are drawn from the actions and targets contained in the Millennium Declaration that was adopted by 189 nations and signed by 147 heads of state and governments during the United Nations Millennium Summit in September 2000 (www.un.org/millenniumgoals/goals.html). Goals three through five of the MDGs relate specifically to women and children (Box 1-3).

Integrative Health Care

Integrative health care encompasses complementary and alternative therapies in combination with conventional Western modalities of treatment. Many popular alternative healing modalities offer human-centered care based on philosophies that recognize the value of the client’s input and honor the individual’s beliefs, values, and desires. The focus of these modalities is on the whole person, not just on a disease complex. Clients often find that alternative modalities are more consistent with their own belief systems and also allow for more client autonomy in health care decisions (Fig. 1-1). Examples of alternative modalities include acupuncture, macrobiotics, herbal medicines, massage therapy, biofeedback, meditation, yoga, and chelation therapy. Complementary and alternative therapies are included throughout the text and will be identified with an icon (![]() ).

).

The Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) in the United States supports research and evaluation of various alternative and complementary modalities and provides information to health care consumers about such modalities. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) incorporates the work of the OAM in its mission and function.

Problems with the U.S. Health Care System

Structure of the Health Care Delivery System

The health care delivery system offers opportunities for nurses to alter nursing practice and improve the way care is delivered through managed care, integrated delivery systems, and redefined roles. Consumer participation in health care decisions is increasing, information is available on the Internet, and care is provided in a technology-intensive environment (Tiedje, Price, & You, 2008).

Reducing Medical Errors

Medical errors are a leading cause of death in the United States and result in as many as 98,000 deaths per year (Gauthier & Serber, 2005). An investigation by the Hearst media corporation concluded that about 200,000 deaths per year occurred because of preventable medical errors and infections (Harmon, 2009). In Canada adverse events are implicated in up to 23,750 deaths per year (French, 2006). Since the Institute of Medicine released its 1999 report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, a concerted effort has been under way to analyze causes of errors and develop strategies to prevent them. Recognizing the multifaceted causes of medical errors, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2000) prepared a fact sheet, 20 Tips to Help Prevent Medical Errors, for clients and the public. Clients are encouraged to be knowledgeable consumers of health care and to ask questions of providers, including physicians, midwives, nurses, and pharmacists.

In 2002 the National Quality Forum published a list of 27 events that should never occur in a health care facility (Shalo, 2007). The list was updated in 2006 with the addition of one event. Of these 28 events, 4 pertain directly to maternity and newborn care (Box 1-4). The National Quality Forum also published Safe Practices for Better Healthcare (www.qualityforum.org). The 30 safe practices included should be used in all applicable health care settings to reduce the risk of harm that results from processes, systems, and environments of care. Box 1-5 contains a selection of practices from that document.

In August 2007 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a rule that denies payment for eight hospital-acquired conditions that became effective October 2008 (O’Reilly, 2008). Five of the conditions are also on the National Quality Forum list. Conditions that might pertain to maternity nursing include a foreign object retained after surgery, air embolism, blood incompatibility, falls and trauma, and catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Almost 1300 U.S. hospitals waive (do not bill for) costs associated with “never events” (O’Reilly).

High Cost of Health Care

Health care is one of the fastest-growing sectors of the U.S. economy. Currently, 16% of the gross domestic product is spent on health care, with an expectation that the proportion will rise to 20% by 2016 (Roehr, 2008). A shift in demographics, an emphasis on high-cost technology, and the liability costs of a litigious society contribute to the high cost of care. Most researchers agree that caring for the increased number of low-birth-weight (LBW) infants in neonatal intensive care units contributes significantly to the overall health care costs. Midwifery care has helped contain some health care costs. However, not all insurance carriers reimburse nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists as direct care providers. Nor do they reimburse for all services provided by nurse-midwives, a situation that continues to be a problem. Nurses must become involved in the politics of cost containment because they, as knowledgeable experts, can provide solutions to many health care problems at a relatively low cost.

Limited Access to Care

Barriers to access must be removed so pregnancy outcomes can be improved. The most significant barrier to access is the inability to pay. The number of uninsured people in the United States in 2006 was 47 million or 15.8% of the population (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2007). A more recent study reports that 86.7 million Americans were uninsured at one point during 2007-2008 (Pifer-Bixler, 2009). Lack of transportation and dependent child care are other barriers. In addition to a lack of insurance and high costs, a lack of providers for low-income women exists because many physicians either refuse to take Medicaid clients or take only a few such clients. This presents a serious problem because a significant proportion of births is to mothers who receive Medicaid.

Health Care Reform

In early 2010, President Obama signed into law the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The Act aims to make insurance affordable, contain costs, strengthen and improve Medicare and Medicaid, and reform the insurance market. There are provisions to promote prevention and improve public health, improve the quality of care for all Americans, reduce waste, fraud, and abuse, and reform the health delivery system. There are some immediate benefits but implementation of the Act will occur over the next several years.

Efforts to Reduce Health Disparities

Significant disparities in morbidity and mortality rates are experienced by African-Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, Alaska Natives, and Asian/Pacific Islanders in comparison with Caucasians. Shorter life expectancy, higher infant and maternal mortality rates, more birth defects, and more sexually transmitted infections are found among these ethnic and racial minority groups. The disparities are thought to result from a complex interaction among biologic factors, environment, and health behaviors. Disparities in education and income are associated with differences in morbidity and mortality.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Health Disparities Collaboratives are part of a national effort with the goal of eliminating disparities and improving delivery systems of health care for all people in the United States who are cared for in HRSA-supported health centers (Calvo, 2006). The National Institutes of Health has a commitment to improve the health of minorities and provides funding for research and training of minority researchers (www.nih.gov). The National Institute of Nursing Research has included the goal of reducing disparities in its strategic plan and supports research for this purpose. A broad public health perspective is needed to reduce these disparities (Satcher & Higginbotham, 2008).

Health Literacy

Health literacy involves a spectrum of abilities, ranging from reading an appointment slip to interpreting medication instructions. These skills must be assessed routinely to recognize a problem and accommodate clients with limited literacy skills. Most client education materials are written at too high a level for the average adult (Wilson, 2009).

As a result of the increasingly multicultural U.S. population, there is a more urgent need to address health literacy as a component of culturally and linguistically competent care. Health care providers contribute to health literacy by using simple, common words, avoiding jargon, and assessing whether the client understands the discussion. Speaking slowly and clearly and focusing on what is important will increase understanding.

Trends in Fertility and Birth Rate

Fertility trends and birth rates reflect women’s needs for health care. Box 1-6 defines biostatistical terminology useful in analyzing maternity health care. In 2008 the fertility rate, births per 1000 women from 15 to 44 years of age, was 68.7 (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2010). The highest birth rates occurred among women between 20 and 29 years of age. The birth rate, number of live births in 1 year per 1000 population, was 14.3 in 2008; the teen birth rate was 41.5. In 2008 the proportion of births by unmarried women varied widely among racial groups in the United States: African-American, 72.3%; Hispanic, 52.5%; and non-Hispanic white, 28.6% (Hamilton et al.).

Low Birth Weight and Preterm Birth

The risks of morbidity and mortality increase for newborns weighing less than 2500 g (5 lb, 8 oz)—low birth weight (LBW) infants. Multiple births contribute to the incidence of LBW. The twin birth rate was 32.1 per 1000 in 2006. The downward trend in the birthrate of higher-order multiples (triplet, quadruplet, and greater) continued in 2006, with a rate of 153.3 per 100,000. In 2003, 58% of all multiple births were LBW. In 2008 the incidence of LBW infants was 8.2% (Hamilton et al., 2010). African-American infants are more than twice as likely as non-Hispanic white infants to be of LBW and to die in the first year of life. For African-American births, the incidence of LBW was 13.7%, whereas the rate was 7.2% for non-Hispanic white births and 6.9% for Hispanic births (Hamilton et al.). Cigarette smoking is associated with LBW, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction. In 2007, 13.2% of pregnant women smoked including 18.1% of non-Hispanic white women, 10.6% non-Hispanic black women, and 2.8% of Hispanic women (Heron, Sutton, Xu, Ventura, Strobino, & Guyer, 2010).

The percentage of infants born preterm (i.e., born before 38 weeks of gestation) was 12.3% in 2008. There was variation in the percentage according to race and Hispanic origin: 17.5% for non-Hispanic black births, 12.1% for Hispanic births, and 11.1% for non-Hispanic white births (Hamilton et al., 2010). Multiple births accounted for 3.4% of births in 2006, with most of the increase associated with increased use of fertility drugs and older age at childbearing (Martin, Kung, Mathews, Hoyert, Strobino, Guyer, et al., 2008).

Infant Mortality in the United States

A common indicator of the adequacy of prenatal care and the health of a nation as a whole is the infant mortality rate, the number of deaths of infants younger than 1 year of age per 1000 live births. The neonatal mortality rate is the number of deaths of infants younger than 28 days of age per 1000 live births. The perinatal mortality rate is the number of stillbirths plus the number of neonatal deaths per 1000 live births. The U.S. infant mortality rate for 2007 was 6.77 (Heron et al., 2010). The disparity in infant mortality rate between African-American infants and Caucasian infants has increased over time. The infant mortality rate continues to be higher for non-Hispanic black babies (13.63 per 1000) than for non-Hispanic whites (5.76 per 1000) and Hispanic (5.62 per 1000) babies (Heron et al.). Limited maternal education, young maternal age, unmarried status, poverty, lack of prenatal care, and smoking appear to be associated with higher infant mortality rates. Poor nutrition, alcohol use, and maternal conditions such as poor health or hypertension also are important contributors to infant mortality. To address the factors associated with infant mortality, a shift from the current emphasis on high-technology medical interventions to a focus on improving access to preventive care for low-income families must occur.

The leading cause of death in the neonatal period is congenital anomalies. Other causes of neonatal death include disorders related to short gestation and LBW, sudden infant death, respiratory distress syndrome, and the effects of maternal complications. Racial differences in the infant mortality rates continue to challenge public health experts. Increased rates of survival during the neonatal period have resulted largely from high-quality prenatal care and the improvement in perinatal services, including technologic advances in neonatal intensive care and obstetrics.

Commitment at national, state, and local levels is required to reduce the infant mortality rate. More research is needed to identify the extent to which financial, educational, sociocultural, and behavioral factors individually and collectively affect perinatal morbidity and mortality. Barriers to care must be removed and perinatal services modified to meet contemporary health care needs.

International Infant Mortality Trends

In 2005, the infant mortality rate of Canada (5.4/1000) ranked twenty-fifth, and that of the United States (6.9/1000) ranked twenty-ninth, when compared with those of other industrialized nations (Heron et al., 2010). Decreases in the infant mortality rate in the United States do not keep pace with the rates of other industrialized countries. One reason for this is the high rate of LBW infants in the United States in contrast with the rates in other countries.

Maternal Mortality Trends

Worldwide, approximately 1600 women die each day of problems related to pregnancy or childbirth; many of these deaths are preventable. In the United States in 2006, the annual maternal mortality rate (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) was 13.3 (Heron, Hoyert, Murphy, Xu, Kochanek, & Tejada-Vera, 2009). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began working with national and international groups in 2001 to develop and implement programs to promote safe motherhood (Jones, 2008). Although the overall number of maternal deaths is small, maternal mortality remains a significant problem because a high proportion of deaths are preventable, primarily through improving the access to and use of prenatal care services. In the United States, there is significant racial disparity in the rates of maternal death: black women (32.7), Hispanic women (10.2), and Caucasian women (9.5) (Heron et al.). The leading causes of maternal death attributable to pregnancy differ over the world. In general, three major causes have persisted for the last 50 years: hypertensive disorders, infection, and hemorrhage. The three leading causes of maternal mortality in the United States today are gestational hypertension, pulmonary embolism, and hemorrhage. Factors that are strongly related to maternal death include age (younger than 20 years and 35 years or older), lack of prenatal care, low educational attainment, unmarried status, and non-Caucasian race. The Healthy People 2010 goal of 3.3 maternal deaths per 100,000 posed a significant challenge and was not achieved. Worldwide strategies to reduce maternal mortality rates include improving access to skilled attendants at birth, providing postabortion care, improving family planning services, and providing adolescents with better reproductive health services (Millennium Development Goals, 2008).

Increase in High Risk Pregnancies

Approximately 500,000 of the 4 million births that occur in the United States each year are categorized as high risk because of maternal or fetal complications. The diagnosis of high risk imposes a situational crisis on the family (e.g., loss of pregnancy before the anticipated date, development of gestational diabetes mellitus with its potential complications, or birth of a neonate who does not meet cultural, societal, or familial norms and expectations).

Identification of the risks, together with appropriate and timely intervention during the perinatal period, can prevent morbidity and mortality among mothers and infants. With the changing demographics in the United States, more women and families can be identified as at risk because of factors other than biophysical criteria. The increasing numbers of homeless, single, or uninsured pregnant women who have no access to prenatal care during any stage of pregnancy and the behaviors and lifestyles that pose a risk to the health of the mother and fetus contribute to the problem.

Over 90% of pregnant women take prescription or nonprescription drugs, social drugs (e.g., alcohol, tobacco), or illicit drugs sometime during pregnancy (The Merck Manual Online Medical Library, 2007). Drug use in pregnancy has contributed to higher incidences of prematurity, LBW, congenital defects, learning disabilities, and withdrawal symptoms in infants. Alcohol use in pregnancy has been associated with miscarriages, mental retardation, LBW, and alcohol-related birth defects.

More than one third (35.2%) of women in the United States are obese (body mass index of 30 or greater), with adults ages 45 to 64 having the highest prevalence. Obesity in women demonstrates significant racial disparities: 53.2% of non-Hispanic black women, 41.8% of Mexican-American women, and 31.6% of non-Hispanic white women ages 20 years and older are obese (National Center for Health Statistics, 2009). Almost 20% of women who give birth in the United States are obese. The two most frequently reported maternal medical risk factors are hypertension associated with pregnancy and diabetes, both of which are associated with obesity. Obesity in pregnancy is associated with the use of increased health care services and hospital stays that are longer (Chu, Bachman, Callaghan, Whitlock, Dietz, Berg, et al., 2008).

High risk pregnancy is a critical problem for modern medical and nursing care. The new social emphasis on the quality of life and the wanted child has resulted in a reduction of family size and the number of unwanted pregnancies. At the same time, technologic advances have facilitated pregnancies in previously infertile couples. As a consequence, emphasis is on the safe birth of normal infants who can develop to their potential. Scientific and technologic advances have allowed perinatal health care to reach a level far beyond that previously available.

Early and ongoing risk assessment is a crucial component of perinatal care. Conditions associated with perinatal morbidity and mortality can be prevented, treated, or referred to more skilled health care providers. Factors to consider when determining a woman’s risk status include resources available locally to treat the condition, availability of appropriate facilities for transport if needed, and determination of the best match for the woman’s needs. In the past, risk factors were evaluated only from a medical viewpoint; therefore, only adverse medical, obstetric, or physiologic conditions were considered to place the woman at risk. Today a more comprehensive approach to high risk pregnancy is used, and the factors associated with high risk childbearing are grouped into broad categories based on threats to health and pregnancy outcome.

Regionalization of Perinatal Health Care Services

Not all facilities develop and maintain the full spectrum of services required for high risk perinatal clients. As a consequence, regionalization of hospital-based perinatal health care services occurred and facilities within a geographic region were organized to provide different levels of care. This system of coordinated care was also applied to preconception and ambulatory prenatal care services.

Guidelines have been established regarding the level of care that can be expected at any given facility. In ambulatory settings, providers must distinguish themselves by the level of care they provide. Basic care is provided by obstetricians, family physicians, certified nurse-midwives, and other advanced practice clinicians approved by local governance. Routine risk-oriented prenatal care, education, and support are provided. Providers offering specialty care are obstetricians who must provide fetal diagnostic testing and management of obstetric and medical complications in addition to basic care. Subspecialty care is provided by maternal-fetal medicine specialists and includes the aforementioned in addition to genetic testing, advanced fetal therapies, and management of severe maternal and fetal complications (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2007).

Specialty hospital care includes these personnel requirements in addition to providing care of high risk mothers and fetuses, stabilization of ill neonates before transfer, and care of preterm infants with a birth weight of 1500 g or more. Women in preterm labor or those with impending births at 32 weeks of gestation or less should be transferred for subspecialty care. Additional criteria for subspecialty care include provision of comprehensive perinatal care for women and infants of all risk categories, evaluation and use of new high risk technologies and therapies, and data collection and retrieval. Collaboration among providers to meet the woman’s needs is the key to reducing perinatal morbidity and mortality (AAP & ACOG, 2007).

High-Technology Care

Advances in scientific knowledge and the large number of high risk pregnancies have contributed to a health care system that emphasizes high-technology care. Maternity care has extended to preconception counseling, more and better scientific techniques to monitor the mother and fetus, more definitive tests for hypoxia and acidosis, and neonatal intensive care units. The labors of virtually all women who give birth in hospitals are monitored electronically despite the lack of evidence of efficacy of such monitoring. The numbers of assisted labors and births are increasing. Internet-based information is available to the public that enhances interactions among health care providers, families, and community providers. Point-of-care testing is available. Personal data assistants are used to enhance comprehensive care; the medical record is increasingly in electronic form.

Telehealth is an umbrella term for the use of communication technologies and electronic information to provide or support health care when the participants are separated by distance. Telehealth permits specialists, including nurses, to provide health care and consultation when distance separates them from those needing care. This technology has the potential to save billions of dollars annually for health care, but these technologic advances have also contributed to higher health care costs.

Strides are being made in identifying genetic codes, and genetic engineering is taking place. Women’s health has expanded to emphasize care of older women, new cancer-screening techniques, advances in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, and work on an AIDS vaccine. In general, high-technology care has flourished, whereas “health” care has become relatively neglected. Nurses must use caution and prospective planning and assess the effect of the emerging technology.

Community-Based Care

A shift in settings, from acute care institutions to ambulatory settings including the home, has occurred (see Chapter 2). Even childbearing women at high risk are cared for on an outpatient basis or in the home. Technology previously available only in the hospital is now found in the home. This has affected the organizational structure of care, the skills required in providing such care, and the costs to consumers.

Home health care also has a community focus. Nurses are involved in providing care for women and infants in homeless shelters, in caring for adolescents in school-based clinics, and in promoting health at community sites, churches, and shopping malls. Nursing education curricula are increasingly community based.

Childbirth Practices

Prenatal care can promote better pregnancy outcomes by providing early risk assessment and promoting healthy behaviors such as improved nutrition and smoking cessation. Prenatal care ideally begins before pregnancy because early decisions lay the foundation for the entire perinatal year. If at all possible, education continues in each trimester of pregnancy, and extends through the early postpartum weeks. Some health care providers today promote preconception care as an important component of perinatal services. Preconception or early pregnancy classes also emphasize health-promoting behavior as well as choices of care.

In 2006, 69% of all women received care in the first trimester. There is disparity in receiving prenatal care by race and ethnicity: 12.2% of Hispanic women, 11.8% of non-Hispanic blacks, and 5.2% of non-Hispanic whites received late or no prenatal care (Heron et al., 2010). In spite of these statistics, substantial

gains have been made in the use of prenatal care since the early 1990s, which is attributed to the expansion in the 1980s of Medicaid coverage for pregnant women.

Women can choose physicians or nurse-midwives as primary care providers. In 2006, physicians attended 92% of all births and certified nurse-midwives attended 7.4% (Heron et al., 2010). Women who choose nurse-midwives as their primary providers participate more actively in childbirth decisions and receive fewer interventions during labor. The rate of vaginal births after cesarean (VBACs) declined, whereas cesarean births increased to 31.8% of live births in the United States in 2007. The Healthy People 2010 goal of 15% was not met.

Certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) are registered nurses with education in the two disciplines of nursing and midwifery. Certified midwives (direct-entry midwives) are educated only in the discipline of midwifery. In the United States, certification of midwives is through the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM), the professional association for midwives. The Royal College of Midwives is the professional association for midwives in the United Kingdom. In Canada, the Association of Ontario Midwives is the professional association, and the College of Midwives of Ontario is the regulatory body for midwives in Ontario; the other provinces of Canada have similar regulatory bodies (e.g., College of Midwives of British Columbia). Many national associations belong to the International Confederation of Midwives, which comprises 97 member associations from 86 countries in the Americas and Europe, Africa, and the Asia-Pacific region.

With family-centered care, fathers, partners, grandparents, siblings, and friends may be present for labor and birth. Fathers or partners may be present for cesarean births. Fathers or partners may participate in vaginal births by “catching the baby” or cutting the umbilical cord or both (Fig. 1-2). Doulas—trained and experienced female labor attendants—may be present to provide a continuous, one-on-one caring presence throughout the labor and birth. Ideally, newborns are placed skin-to-skin with the mother immediately after birth and are encouraged to breastfeed as soon as possible. Nonseparation is common; neonates often remain in the room with their parents and may never transfer to a newborn nursery. Parents actively participate in newborn care on mother/baby units, in nurseries, and in neonatal intensive care units.

FIG. 1-2 Father “catching” newborn son. Mother is reaching down to help birth the baby. (Courtesy Darren and Julie Nelson, Loveland, CO.)

Neonatal security in the hospital setting is of concern. A significant number of cases of “baby-napping” and of sending parents home with the wrong baby have been reported. Security systems have been placed in nurseries, and nurses are required to wear photo identification or some other security badge.

Discharge of a mother and baby within 24 hours of birth has created a growing need for follow-up or home care. In some settings, discharge may occur as early as 6 hours after birth. Legislation has been enacted to ensure that mothers and babies are permitted to stay in the hospital for at least 48 hours after vaginal birth and 96 hours after cesarean birth although they may choose to leave earlier. Focused and efficient teaching is necessary to enable the parents and infant to make the transition safely from the hospital to the home.

Involving Consumers and Promoting Self-Management

Self-management is appealing to both clients and the health care system because of its potential to reduce health care costs. Maternity care is especially suited to self-management because childbearing is primarily health focused, women are usually well when they enter the system, and visits to health care providers can present the opportunity for health and illness interventions. Measures to improve health and reduce risks associated with poor pregnancy outcomes and illness can be addressed. Topics such as nutrition education, stress management, smoking cessation, alcohol and drug treatment, prevention of violence, improvement of social supports, and parenting education are appropriate for such encounters.

International Concerns

Female genital mutilation, infibulation (surgical closure of the labia majora), and circumcision are terms used to describe procedures in which part or all of the female external genitalia are removed for cultural or nontherapeutic reasons (WHO, 2006). Worldwide, many women undergo such procedures. With the growing number of immigrants from Africa and other countries where female genital mutilation is practiced, nurses in the United States and Canada will increasingly encounter women who have undergone the procedure. Women who have undergone the procedure are significantly more likely to have adverse obstetric outcomes resulting in one or two additional perinatal deaths per 100 births (WHO, 2006). Ethical dilemmas arise when the woman requests that after birth the perineum be repaired as it was after infibulation and the health care provider believes that such repair is unethical. The International Council of Nurses and other health professionals have spoken out against the procedures that result in mutilation as harmful to women’s health.

Health of Women

Various factors and conditions affect women’s health. Race is a major factor: Caucasian women have a life expectancy at birth of 80.7 years, in contrast with 77.0 years for African-American women (Miniňo, Xu, Kochanek, & Tejada-Vera, 2009). In 2010, there were an estimated 207,090 new cases of invasive breast cancer in women in the United States, and 39,840 women were expected to die of the disease (American Cancer Society, 2010). Early detection of breast cancer through mammography can reduce the mortality rate resulting from this type of cancer. However, because of lack of information or lack of insurance and access, many women never have mammograms. Wide disparity exists between Caucasian women and women of other races and between older and younger women in their rates of mammography, detection, and treatment of breast cancer, and in their survival rates (see Chapter 10).

The population has grown older: approximately 50 million women are older than 50 years of age; 51 is the median age for menopause. Hormone replacement therapy for menopausal women has been used for many years and has both benefits and risks (see Chapter 6).

Violence is a major factor affecting women (see Chapter 5). Violence includes battery, rape or other sexual assaults, and attacks with various weapons. Rates of reported intimate partner violence have increased, possibly because of better assessment and reporting mechanisms. Approximately 4% to 8% of pregnant women are battered; the incidence of battering increases during pregnancy. Violence is associated with complications of pregnancy such as bleeding. Alcoholism and substance abuse by the woman and her abuser are associated with violence and homelessness, which affect a growing number of women and children and place them at risk for a variety of health problems.

The rates of pregnancy and elective abortion among adolescents declined from 1991 through 2005 but the pregnancy rate increased between 2005 and 2007; rates are higher in the United States than in any other industrialized country. Single mothers gave birth to 39.7% of the babies born in the United States in 2007 (Heron et al., 2010). Births to unmarried women are frequently related to less favorable outcomes, such as LBW infants or preterm birth.

Trends in Nursing Practice

The increasing complexity of care for maternity and women’s health clients has contributed to specialization of nurses working with these clients. This specialized knowledge is gained through experience, advanced degrees, and certification programs. Nurses in advanced practice (e.g., nurse practitioners and nurse-midwives) may provide primary care throughout a woman’s life, including during the pregnancy cycle. In some settings, the clinical nurse specialist and nurse practitioner roles are blended, and nurses deliver high-quality, comprehensive, and cost-effective care in a variety of settings. Lactation consultants provide services in the hospital setting, in clinics and physician offices, and during home visits.

Nursing Interventions Classification

When the National Institute of Medicine proposed that all client records be computerized by the year 2000, a need for a common language to describe the contributions of nurses to client care became evident. Nurses from the University of Iowa developed a comprehensive standardized language that describes interventions that are performed by generalist or specialist nurses. This language is included in the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (Dochterman & Bulechek, 2004). Interventions commonly used by maternal-child nurses include those in Box 1-7.

Evidence-Based Practice

Evidence-based practice—providing care based on evidence gained through research and clinical trials—is increasingly emphasized. Although not all practice can be evidence based, practitioners must use the best available information on which to base their interventions. The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) Standards and Guidelines for Professional Nursing Practice in the Care of Women and Newborns (AWHONN, 2009) and the Standards for Professional Perinatal Nursing Practice and Certification in Canada (AWHONN, 2002) include an evidence-based approach to practice. Discussion of nursing care and evidence-based practice boxes throughout this text provide examples of evidence-based practice in perinatal and women’s health nursing (see Evidence-Based Practice box).

Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database was first planned in 1976 with a small grant from the World Health Organization to Dr. Iain Chalmers and colleagues at Oxford. In 1993, the Cochrane Collaboration was formed, and the Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials became known as the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database. The Cochrane Collaboration oversees up-to-date, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials of health care and disseminates these reviews. The premise of the project is that these types of studies provide the most reliable evidence about the effects of care.

The evidence from these studies should encourage practitioners to implement useful measures and to abandon those that are useless or harmless. Studies are ranked in six categories:

2. Forms of care that are likely to be beneficial

3. Forms of care with a trade-off between beneficial and adverse effects

4. Forms of care with unknown effectiveness

5. Forms of care that are unlikely to be beneficial

6. Forms of care that are likely to be ineffective or harmful

Practices that have been reviewed by the Cochrane Collaboration as well as other evidence for practice are identified with a symbol (![]() ) throughout this text.

) throughout this text.

Joanna Briggs Institute

Established in 1996 as an initiative of the Royal Adelaide Hospital and the University of Adelaide in Australia, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) uses a collaborative approach for evaluating evidence from a range of sources (www.joannabriggs.edu.au). The JBI has formed collaborations with a variety of universities and hospitals around the world including in the United States and Canada. In 2007, the JBI adopted the following grades of recommendation for evidence of feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness, and effectiveness: A, strong support that merits application; B, moderate support that warrants consideration of application; and C, not supported (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2008). The JBI provides another source for perinatal nurses to access information to support evidence-based practice.

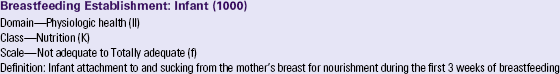

Outcomes-Oriented Practice: Outcomes of care (that is, the effectiveness of interventions and quality of care) are receiving increased emphasis. Outcomes-oriented care measures effectiveness of care against benchmarks or standards. It is a measure of the value of nursing using quality indicators and answers the question, “Did the client benefit or not benefit from the care provided?” (Moorhead, Johnson, & Maas, 2004). The Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) is an example of an outcome system important for nursing. Its use is required by the CMS in all home health organizations that are Medicare accredited. The Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) is an effort to identify outcomes and related measures that can be used for evaluation of care of individuals, families, and communities across the care continuum (Moorhead et al.). An example of outcomes classification is provided in Table 1-1.

TABLE 1-1

NURSING OUTCOMES CLASSIFICATION

Biancuzzo, M. (2003). Breastfeeding the newborn: Clinical strategies for nurses (2nd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Henderson, A., Pincombe, J., & Stamp, G. (2000). Assisting women to establish breastfeeding: Exploring midwives practices. Breastfeeding Review, 8 (3), 11-17.

Lang, S. (2002). Breastfeeding special care babies (2nd ed.). London: Bailliere Tindall.

Lawrence, R.A., & Lawrence, R.M. (1999). Breastfeeding: A guide for the medical professional (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Minchin, M. (1989). Positioning for breastfeeding. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care and Education, 16 (2), 67-80.

Mulford, C. (1992). The mother-baby assessment (MBA): An “Apgar Score” for breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation, 8 (2), 79-82.

Neifert, M., & Seacat, J. (1986). A guide to successful breastfeeding. Contemporary Pediatrics, 3, 1-14.Page-Goertz, S. (1989). Discharge planning for the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatric Nursing, 15 (5), 543-544.

Righard, L., & Alade, M. (1992). Sucking technique and its effect on success of breastfeeding. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care and Education, 19 (4), 185-189.

Riordan, J., & Auerbach, K. (1999). Breastfeeding and human lactation (2nd ed.). Boston: Jones and Bartlett.

Shrago, L., & Bocar, D. (1990). The infant’s contribution to breastfeeding. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, 19 (3), 209-215.

Walker, M. (1989). Functional assessment of infant breastfeeding patterns. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care and Education, 16 (3), 140-147.

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., & Maas, M. (Eds.). (2000). Nursing outcomes classification (NOC) (3rd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

A Global Perspective: Advances in medicine and nursing have resulted in increased knowledge and understanding in the care of mothers and infants and reduced perinatal morbidity and mortality rates. However, these advances have affected predominantly the industrialized nations. For example, the majority of the 3.2 million children living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or AIDS acquired the infection through perinatal transmission and live in sub-Saharan Africa.

As the world becomes smaller because of travel and communication technologies, nurses and other health care providers are gaining a global perspective and participating in activities to improve the health and health care of people worldwide. Nurses participate in medical outreach, providing obstetric, surgical, ophthalmologic, orthopedic, or other services (Fig. 1-3); attend international meetings; conduct research; and provide international consultation. International student and faculty exchanges occur. More articles about health and health care in various countries are appearing in nursing journals. Several schools of nursing in the United States are World Health Organization Collaborating Centers.

Standards of Practice and Legal Issues in Delivery of Care

Nursing standards of practice in perinatal and women’s health nursing have been described by several organizations, including the ANA, which publishes standards for maternal-child health nursing; AWHONN, which publishes standards of practice and education for perinatal nurses (Box 1-8); ACNM, which publishes standards of practice for midwives; and the National Association of Neonatal Nurses (NANN), which publishes standards of practice for neonatal nurses. These standards reflect current knowledge, represent levels of practice agreed on by leaders in the specialty, and can be used for clinical benchmarking.

In addition to these more formalized standards, agencies have their own policy and procedure books that outline standards to be followed in that setting. In legal terms, the standard of care is that level of practice that a reasonably prudent nurse would provide in the same or similar circumstances. In determining legal negligence, the care given is compared with the standard of care. If the standard was not met and harm resulted, negligence occurred. The number of legal suits in the perinatal area has typically been high. As a consequence, malpractice insurance costs are high for physicians, nurse-midwives, and nurses who work in labor and birth settings.

Risk Management

Risk management is an evolving process that identifies risks, establishes preventive practices, develops reporting mechanisms, and delineates procedures for managing lawsuits. Nurses should be familiar with concepts of risk management and their implications for nursing practice. These concepts can be viewed as systems of checks and balances that ensure high-quality client care from preconception until after birth. Effective risk management minimizes the risk of injury to clients and the number of lawsuits against nurses, doctors, and hospitals. Each facility or site develops site-specific risk management procedures based on accepted standards and guidelines. The procedures and guidelines must be reviewed periodically.

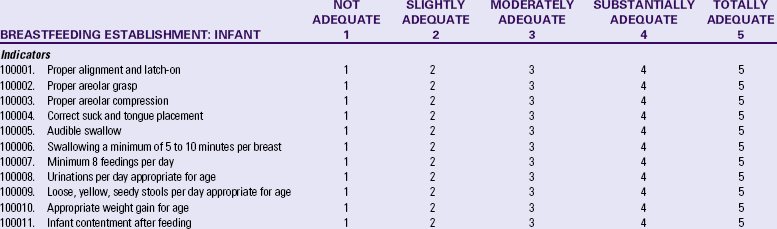

To decrease risk of errors in the administration of medications, The Joint Commission (TJC) (2009) developed a list of abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols not to use (Table 1-2). In addition, each agency must develop its own list.

TABLE 1-2

THE JOINT COMMISSION “DO NOT USE” LIST

∗(For possible future inclusion in the Official “Do Not Use” List)

Source: Official “Do Not Use” list. Available at www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/DoNotUseList. Updated March 5, 2009. Accessed February 9, 2010.

Sentinel Events

TJC describes a sentinel event as “an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof. Serious injury specifically includes loss of limb or function.” These events are called sentinel because they signal a need for an immediate investigation and response (TJC, 2010). Reportable sentinel events in perinatal nursing include any maternal death related to the process of birth, any perinatal death unrelated to a congenital condition in an infant having a birth weight greater than 2500 g, severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (bilirubin greater than 30 mg/dL), and infant discharge to the wrong family (TJC). Other sentinel events that may occur in perinatal nursing include hemolytic transfusion reaction involving major blood group incompatibilities, leaving a foreign body (e.g., sponge or forceps) in a client after surgery, and falls that result in death or major permanent loss of function that is a direct result of the injuries caused by the fall. When a sentinel event occurs, there must be a root cause analysis and an action plan formulated that identifies strategies to reduce the risk of future similar events.

Failure to Rescue

Failure to rescue is used to “evaluate the quality and quantity of nursing care by comparing the number of surgical clients who develop common complications who survive versus those who do not” (Simpson, 2005). As mothers and babies are generally healthy, complications leading to death in obstetrics are comparatively rare. Simpson proposes evaluating the perinatal team’s ability to decrease risk of adverse outcomes by measuring processes involved in common complications and emergencies in obstetrics. Key components of failure to rescue are (1) careful surveillance and identification of complications, and (2) acting quickly to initiate appropriate interventions and activating a team response. For the perinatal nurse, this involves timely identification of complications, appropriate interventions, and efforts of the team to minimize client harm. Maternal complications that are appropriate for process measurement are placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, eclampsia, and amniotic fluid embolism (Simpson). Fetal complications include nonreassuring fetal heart rate and pattern, prolapsed umbilical cord, shoulder dystocia, and uterine hyperstimulation (Simpson). Perinatal nurses can use these complications to develop a list of expectations for monitoring, timely identification, interventions, and roles of team members. The list can be used to evaluate the perinatal team’s response.

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) is an effort to provide nurses with the competencies to improve the quality and safety of the systems of health care in which they practice (Cronenwett, Sherwood, Barnsteiner, Disch, Johnson, Mitchell, et al., 2007). The competencies for nursing delineated by the Institute of Medicine (2003) (Box 1-9) were adapted by QSEN faculty members and defined describing essential features of a competent and respected nurse. They then developed knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) for each competency. Incorporation of these KSAs into prelicensure education for nurses would assist faculty to plan learning experiences to prepare respected and qualified nurses.

Teamwork and Communication

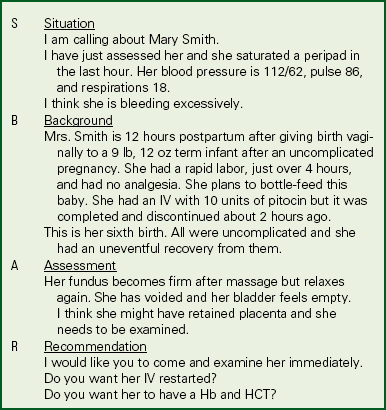

Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation

The situation background assessment recommendation (SBAR) technique gives a specific framework for communication among health care providers. SBAR is an easy to remember, useful, concrete mechanism for communicating important information that requires a clinician’s immediate attention (Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, n.d.) (Box 1-10). Failure to communicate is one of the major reasons for errors in health care. The SBAR technique has the potential to serve as a means to reduce errors.

TeamSTEPPS

TeamSTEPPS was developed by the Department of Defense’s Patient Safety Program in collaboration with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as a teamwork system for health professionals to provide higher quality, safer client care (http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/about-2cl_3.htm). It provides an evidence-base to improve communication and teamwork skills. Through this system medical teams use information, people, and resources to achieve the best possible clinical outcomes, increase team awareness and clarify roles and responsibilities of team members, resolve conflicts and improve sharing of information, and eliminate barriers to quality and safety.

Ethical Issues in Perinatal Nursing and Women’s Health Care

Ethical concerns and debates have multiplied with the increased use of technology and with scientific advances. For example, with reproductive technology, pregnancy is now possible in women who thought they would never bear children, including some who are menopausal or postmenopausal. Should scarce resources be devoted to achieving pregnancies in older women? Is giving birth to a child at an older age worth the risks involved? Should older parents be encouraged to conceive a baby when they may not live to see the child reach adulthood? Should a woman who is HIV positive have access to assisted reproduction services? Should third-party payers assume the costs of reproductive technology such as the use of induced ovulation and in vitro fertilizations? With induced ovulation and in vitro fertilization, multiple pregnancies occur, and multifetal pregnancy reduction (selectively terminating one or more fetuses) may be considered. Questions about informed consent and allocation of resources must be addressed with innovations such as intrauterine fetal surgery, fetoscopy, therapeutic insemination, genetic engineering, stem cell research, surrogate childbearing, surgery for infertility, “test tube” babies, fetal research, and treatment of very LBW (VLBW) babies. The introduction of long-acting contraceptives has created moral choices and policy dilemmas for health care providers and legislators; that is, should some women (substance abusers, women with low incomes, or women who are HIV positive) be required to take the contraceptives? With the potential for great good that can come from fetal tissue transplantation, what research is ethical? What are the rights of the embryo? Should cloning of humans be permitted? Discussion and debate about these issues will continue for many years. Nurses and clients, as well as scientists, physicians, attorneys, lawmakers, ethicists, and clergy, must be involved in the discussions.

Research in Perinatal Nursing and Women’s Health Care

Research plays a vital role in the establishment of maternity and women’s health science. Research can validate that nursing care makes a difference. For example, although prenatal care is clearly associated with healthier infants, no one knows exactly which nursing interventions produce this outcome. The research into women’s health must increase. In the past, medical researchers rarely included women in their studies, so more research in this area is crucial. Many possible areas of research exist in maternity and women’s health care. The clinician can identify problems in the health and health care of women and infants. Through research, nurses can make a difference for these clients. Nurses should promote research funding and conduct research on maternity and women’s health, especially concerning the effectiveness of nursing strategies for these clients.

Ethical Guidelines for Nursing Research: Research with perinatal clients may create ethical dilemmas for the nurse. For example, participating in research may cause additional stress to a woman concerned about outcomes of genetic testing or one who is waiting for an invasive procedure. Obtaining amniotic fluid samples or performing cordocentesis poses risks to the fetus. Nurses must protect the rights of human subjects (i.e., clients) in all of their research. For example, nurses can collect data on or care for clients who are participating in clinical trials. The nurse ensures that the participants are fully informed and aware of their rights as subjects. The nurse may be involved in determining whether the benefits of research outweigh the risks to the mother and the fetus. Following the ANA ethical guidelines in the conduct, dissemination, and implementation of nursing research helps nurses ensure that research is conducted ethically (Silva, 1995).

KEY POINTS

• Maternity nursing focuses on women and their infants and families during the childbearing cycle.

• Women’s health nursing focuses on the special physical, psychologic, and social needs of women throughout their life spans.

• Nurses caring for women can play an active role in shaping health care systems to be responsive to the needs of contemporary women.

• Childbirth practices have changed to become more focused on the family and to allow alternatives in care.

• A variety of factors, including race, age, and violence, affect women’s health.

• Canada ranks twenty-fifth and the United States ranks twenty-ninth among industrialized nations in infant mortality rates.

• Integrative medicine combines modern technology with ancient healing practices and encompasses the whole of body, mind, and spirit.

• Evidence-based practice and outcomes orientation are emphasized in current practice.

• Risk management and learning from sentinel events can improve quality of care.

• Healthy People 2020 provides an update on goals for maternal and infant health.

• Research plays a vital role in establishing a scientific base for the care of women and infants.

• Ethical concerns have multiplied with the increasing use of technology and scientific advances.

![]() Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of these Key Points on

Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of these Key Points on ![]()