Pain Management

• Describe breathing and relaxation techniques used for each stage of labor.

• Analyze nonpharmacologic strategies used to enhance relaxation and decrease discomfort during labor.

• Compare pharmacologic methods used to relieve discomfort in different stages of labor and for vaginal or cesarean birth.

• Discuss the use of naloxone (Narcan).

• Create an evidence-based plan to manage the discomfort a woman experiences during childbirth.

• Apply the nursing process to pain management for a woman in labor.

• Summarize the nursing responsibilities appropriate in providing care for a woman receiving analgesia or anesthesia during labor.

Pain is an unpleasant, complex, highly individualized phenomenon with sensory and emotional components. Pregnant women commonly worry about the pain they will experience during labor and birth and about how they will react to and deal with that pain. A variety of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic methods can help the woman or the couple cope with the discomfort of labor. The methods selected depend on the situation, availability, and the preferences of the woman and her health care provider.

Pain During Labor and Birth

The pain and discomfort of labor have two origins, visceral and somatic. During the first stage of labor, uterine contractions cause cervical dilation and effacement. Uterine ischemia (decreased blood flow and therefore local oxygen deficit) results from compression of the arteries supplying the myometrium during uterine contractions. Pain impulses during the first stage of labor are transmitted via the T1 to T12 spinal nerve segment and accessory lower thoracic and upper lumbar sympathetic nerves. These nerves originate in the uterine body and cervix (Blackburn, 2007).

The pain from distention of the lower uterine segment, stretching of cervical tissue as it effaces and dilates, pressure and traction on adjacent structures (e.g., uterine tubes, ovaries, ligaments) and nerves, and uterine ischemia during the first stage of labor is visceral pain. It is located over the lower portion of the abdomen. Referred pain occurs when pain that originates in the uterus radiates to the abdominal wall, lumbosacral area of the back, iliac crests, gluteal area, thighs, and lower back (Blackburn, 2007; Zwelling, Johnson, & Allen, 2006).

During most of the first stage of labor the woman usually has discomfort only during contractions and is free of pain between contractions. Some women, especially those whose fetus is in a posterior position, experience continuous contraction-related low back pain, even in the interval between contractions. As labor progresses and pain becomes more intense and persistent, women become fatigued and discouraged, often experiencing difficulty coping with contractions (Blackburn, 2007; Creehan, 2008; Zwelling et al., 2006).

During the second stage of labor the woman has somatic pain, which is often described as intense, sharp, burning, and well localized. This pain results from stretching and distention of perineal tissues and the pelvic floor to allow passage of the fetus, from distention and traction on the peritoneum and uterocervical supports during contractions, from pressure against the bladder and rectum, and from lacerations of soft tissue (e.g., cervix, vagina, and perineum). As women concentrate on the work of bearing down to give birth to their baby, they may report a decrease in pain intensity (Creehan, 2008). Pain impulses during the second stage of labor are transmitted via the pudendal nerve through S2 to S4 spinal nerve segments and the parasympathetic system (Blackburn, 2007).

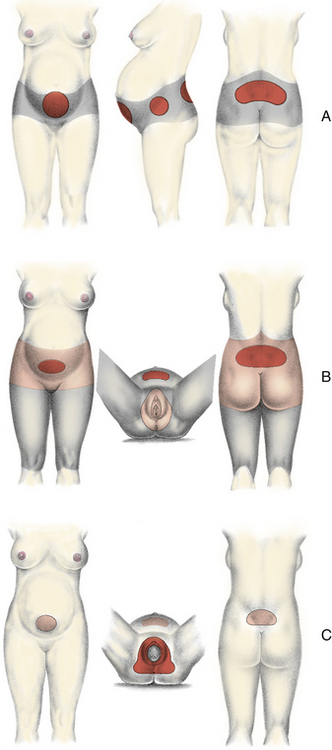

Pain experienced during the third stage of labor and the afterpains of the early postpartum period are uterine, similar to the pain experienced early in the first stage of labor. Areas of discomfort during labor are shown in Figure 17-1.

FIG. 17-1 Discomfort during labor. A, Distribution of labor pain during first stage. B, Distribution of labor pain during transition and early phase of second stage. C, Distribution of pain during late second stage and actual birth. (Gray areas indicate mild discomfort; light pink areas indicate moderate discomfort; dark red areas indicate intense discomfort.)

Perception of Pain

Although the pain threshold is remarkably similar in everyone regardless of gender, social, ethnic, or cultural differences, these differences play a definite role in the person’s perception of and behavioral responses to pain. The effects of factors such as culture, counterstimuli, and distraction in coping with pain are not fully understood. The meaning of pain and the verbal and nonverbal expressions given to pain are apparently learned from interactions within the primary social group. Cultural influences may impose certain behavioral expectations regarding acceptable and unacceptable behavior when experiencing pain.

Pain tolerance refers to the level of pain a laboring woman is willing to endure. When this level is exceeded, she will seek measures to relieve the pain. Factors that influence her pain tolerance level and her request for pharmacologic pain relief measures include a woman’s desire for a natural, vaginal birth; her preparation for childbirth; the nature of her support during labor; and her willingness and ability to participate in nonpharmacologic measures for comfort (Creehan, 2008).

Expression of Pain

Pain results in physiologic effects and sensory and emotional (affective) responses. During childbirth pain gives rise to identifiable physiologic effects. Sympathetic nervous system activity is stimulated in response to intensifying pain, resulting in increased catecholamine levels. Blood pressure and heart rate increase. Maternal respiratory patterns change in response to an increase in oxygen consumption. Hyperventilation, sometimes accompanied by respiratory alkalosis, can occur as pain intensifies and more rapid, shallow breathing techniques are used during contractions. Pallor and diaphoresis may be seen. Gastric acidity increases, and nausea and vomiting are common in the active and transition phases of the first stage of labor. Placental perfusion may decrease, and uterine activity may diminish, potentially prolonging labor and affecting fetal well-being.

Certain emotional (affective) expressions of pain often are seen. Such changes include increasing anxiety with lessened perceptual field, writhing, crying, groaning, gesturing (hand clenching and wringing), and excessive muscular excitability throughout the body.

Factors Influencing Pain Response

Pain during childbirth is unique to each woman. How she perceives or interprets that pain is influenced by a variety of physiologic, psychologic, emotional, social, cultural, and environmental factors (Zwelling et al., 2006).

Physiologic Factors

A variety of physiologic factors can affect the intensity of childbirth pain. Women with a history of dysmenorrhea may experience increased pain during childbirth as a result of higher prostaglandin levels. Back pain associated with menstruation also may increase the likelihood of contraction-related low back pain. Other physical factors that affect pain intensity include fatigue, the interval and duration of contractions, fetal size and position, rapidity of fetal descent, and maternal position (Zwelling et al., 2006).

Endorphins are endogenous opioids secreted by the pituitary gland that act on the central and peripheral nervous systems to reduce pain. The level of endorphins increases during pregnancy and birth in humans. Endorphins are associated with feelings of euphoria and analgesia. The pain threshold may rise as endorphin levels increase, enabling women in labor to tolerate acute pain (Blackburn, 2007).

Culture

The population of pregnant women reflects the increasingly multicultural nature of U.S. society. As nurses care for women and families from a variety of cultural backgrounds, they must have knowledge and understanding of how culture mediates pain. Although all women expect to experience at least some pain and discomfort during childbirth, it is their culture and religious belief system that determines how they will perceive, interpret, and respond to and manage the pain. For example, women with strong religious beliefs often accept pain as a necessary and inevitable part of bringing a new life into the world (Callister, Khalaf, Semenic, Kartchner, & Vehvilainen-Julkunen, 2003). An understanding of the beliefs, values, expectations, and practices of various cultures will narrow the cultural gap and help the nurse to assess the laboring woman’s pain experience more accurately. The nurse can then provide appropriate, culturally sensitive care by using pain relief measures that preserve the woman’s sense of control and self-confidence (see Cultural Considerations box: Some Cultural Beliefs About Pain). Recognize that although a woman’s behavior in response to pain may vary according to her cultural background, it may

not accurately reflect the intensity of the pain she is experiencing. Assess the woman for the physiologic effects of pain and listen to the words she uses to describe the sensory and affective qualities of her pain.

Anxiety

Anxiety is commonly associated with increased pain during labor. Mild anxiety is considered normal for a woman during labor and birth. However, excessive anxiety and fear cause more catecholamine secretion, which increases the stimuli to the brain from the pelvis because of decreased blood flow and increased muscle tension. This action, in turn, magnifies pain perception (Zwelling et al., 2006). Thus as anxiety and fear heighten, muscle tension increases, the effectiveness of uterine contractions decreases, the experience of discomfort increases, and a cycle of increased fear and anxiety begins. Ultimately this cycle will slow the progress of labor. The woman’s confidence in her ability to cope with pain will be diminished, potentially resulting in reduced effectiveness of the pain relief measures being used.

Previous Experience

Previous experience with pain and childbirth may affect a woman’s description of her pain and her ability to cope with the pain. Childbirth, for a healthy young woman, may be her first experience with significant pain, and as a result she may not have developed effective pain coping strategies. She may describe the intensity of even early labor pain as pain “as bad as it can be.” The nature of previous childbirth experiences also may affect a woman’s responses to pain. For women who have had a difficult and painful previous birth experience, anxiety and fear from this past experience may lead to increased pain perception.

Sensory pain for nulliparous women is often greater than that for multiparous women during early labor (dilation less than 5 cm) because their reproductive tract structures are less supple. During the transition phase of the first stage of labor and during the second stage of labor, multiparous women may experience greater sensory pain than nulliparous women because their more supple tissue increases the speed of fetal descent and thereby intensifies pain. The firmer tissue of nulliparous women results in a slower, more gradual descent. Affective pain is usually greater for nulliparous women throughout the first stage of labor but decreases for both nulliparous and multiparous women during the second stage of labor (Lowe, 2002).

Parity may affect perception of labor pain because nulliparous women often have longer labors and therefore greater fatigue. Because fatigue magnifies pain, the combination of increased pain, fatigue, and reduced ability to cope may lead to a greater reliance on pharmacologic support.

Gate-Control Theory of Pain

Even particularly intense pain stimuli can at times be ignored. This is possible because certain nerve cell groupings within the spinal cord, brainstem, and cerebral cortex have the ability to modulate the pain impulse through a blocking mechanism. This gate-control theory of pain helps explain the way hypnosis and the pain relief techniques taught in childbirth preparation classes work to relieve the pain of labor. According to this theory, pain sensations travel along sensory nerve pathways to the brain, but only a limited number of sensations, or messages, can travel through these nerve pathways at one time. Using distraction techniques such as massage or stroking, music, focal points, and imagery reduces or completely blocks the capacity of nerve pathways to transmit pain. These distractions are thought to work by closing down a hypothetic gate in the spinal cord, thus preventing pain signals from reaching the brain. The perception of pain is thereby diminished.

In addition, when the laboring woman engages in neuromuscular and motor activity, activity within the spinal cord itself further modifies the transmission of pain. Cognitive work involving concentration on breathing and relaxation requires selective and directed cortical activity that activates and closes the gating mechanism as well. As labor intensifies, more complex cognitive techniques are required to maintain effectiveness. The gate-control theory underscores the need for a supportive birth setting that allows the laboring woman to relax and use various higher mental activities.

Comfort

Although the predominant medical approach to labor is that it is painful, and the pain must be removed, an alternative view is that labor is a natural process, and women can experience comfort and transcend the discomfort or pain to reach the joyful outcome of birth. Having needs and desires met promotes a feeling of comfort. The most helpful interventions in enhancing comfort are a caring nursing approach and a supportive presence.

Support: ![]() Current evidence indicates that a woman’s satisfaction with her labor and birth experience is determined by how well her personal expectations of childbirth were met and the quality of support and interaction she received from her caregivers (Box 17-1). In addition, satisfaction is influenced by the degree to which she was able to stay in control of her labor and to participate in decision making regarding her labor, including the pain relief measures to be used (Albers, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006).

Current evidence indicates that a woman’s satisfaction with her labor and birth experience is determined by how well her personal expectations of childbirth were met and the quality of support and interaction she received from her caregivers (Box 17-1). In addition, satisfaction is influenced by the degree to which she was able to stay in control of her labor and to participate in decision making regarding her labor, including the pain relief measures to be used (Albers, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006).

The value of the continuous supportive presence of a person (e.g., doula, childbirth educator, family member, friend, nurse, or partner) during labor who provides physical comforting, facilitates communication, and offers information and guidance to the woman in labor has long been known. Emotional support is demonstrated by giving praise and reassurance and conveying a positive, calm, and confident demeanor when caring for the woman in labor (Creehan, 2008). Women who have continuous support beginning early in labor are less likely to use pain medications or epidurals and are more likely to experience a spontaneous vaginal birth and express satisfaction with their childbirth experience. Interestingly, research findings concluded that a more positive effect was achieved when the continuous support was provided by people who were not hospital staff members (Albers, 2007; Berghella, Baxter, & Chauhan, 2008; Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, & Sakala, 2007).

Environment: The quality of the environment can influence pain perception and the laboring woman’s ability to cope with her pain. Environment includes the individuals present (e.g., how they communicate, their philosophy of care including a belief in the value of nonpharmacologic pain relief measures, practice policies, and quality of support) and the physical space in which the labor occurs (Creehan, 2008; Zwelling et al., 2006). Women usually prefer to be cared for by familiar caregivers in a comfortable, homelike setting. The environment should be safe and private, allowing a woman to feel free to be herself as she tries out different comfort measures. Stimuli such as light, noise, and temperature should be adjusted according to her preferences. The environment should have space for movement and equipment such as birth balls. Comfortable chairs, tubs, and showers should be readily available to facilitate participation in a variety of nonpharmacologic pain relief measures. The familiarity of the environment can be enhanced by bringing items from home such as pillows, objects for a focal point, music, and DVDs.

Nonpharmacologic Pain Management

The alleviation of pain is important. Commonly it is not the amount of pain the woman experiences, but whether she meets the goals she set for herself to cope with the pain, that influences her perception of the birth experience as good or bad. The observant nurse looks for clues to the woman’s desired level of control in the management of pain and its relief.

Nonpharmacologic measures are often simple and safe, with few if any major adverse reactions, relatively inexpensive, and can be used throughout labor. Additionally, they provide the woman with a sense of control over her childbirth as she makes choices about the measures that are best for her. During the prenatal period she should explore a variety of nonpharmacologic measures. Techniques she usually finds helpful in relieving stress and enhancing relaxation (e.g., music, meditation, massage, warm baths) may be very effective as components of a plan for managing labor pain. The woman should be encouraged to communicate to her health care providers her preferences for relaxation and pain relief measures and to actively participate in their implementation.

Many of the nonpharmacologic methods for relief of discomfort are taught in different types of prenatal preparation classes, or the woman or couple may have read various books and magazine articles on the subject in advance. Many of these methods require practice for best results (e.g., hypnosis, patterned breathing and controlled relaxation techniques, biofeedback), although the nurse may use some of them successfully without the woman or couple having prior knowledge (e.g., slow-paced breathing, massage and touch, effleurage, counterpressure). Women should be encouraged to try a variety of methods and to seek alternatives, including pharmacologic methods, if the measure being used is no longer effective.

With increasing use of epidural analgesia, nurses may be less likely to encourage women to use nonpharmacologic measures, in part because these methods may be viewed as more complex and time consuming than monitoring a woman receiving an

epidural. Additionally, new nurses may not have had the opportunity to develop skill in the implementation of these methods. It is imperative that perinatal nurses develop a commitment to and expertise in using a variety of nonpharmacologic pain relief strategies in order for women in labor to be comfortable using them. Although there are limited research data to support the effectiveness of many of these nonpharmacologic measures, there are sufficient reports of their benefits from women and health care providers to recommend that nurses encourage their use (Creehan, 2008). (See Evidence-Based Practice box and Clinical Reasoning box.) The analgesic effect of many nonpharmacologic measures is comparable to or even superior to opioids that are administered parenterally (Box 17-2).

Childbirth Preparation Methods

The childbirth education movement began in the 1950s. Today most health care providers recommend or offer childbirth preparation classes for expectant parents. Historically, popular childbirth methods taught in the United States were the Dick-Read method, the Lamaze (psychoprophylaxis) method, and the Bradley (husband-coached childbirth) method (see Community Activity box). Although these three organizations continue to exist, they are now less focused on a “method” approach. Rather, women are assisted to develop their birth philosophy and inner knowledge and then choose from a variety of skills to use to cope with the labor process. Many childbirth educators teach a variety of techniques that originated in several different organizations or publications. Women are encouraged to choose the techniques that work best for them.

Gaining popularity are methods developed and promoted by Birthing From Within, Birthworks, Association of Labor Assistants and Childbirth Educators (ALACE), Childbirth and Postpartum Professional Association (CAPPA), and HypnoBirthing, to name a few. These methods offer classes and other services that focus on fostering a woman’s confidence in her innate ability to give birth. The woman or couple is helped to recognize the uniqueness of their pregnancy and childbirth experience (see Resources on the Evolve website).

Relaxation and Breathing Techniques

Focusing and Relaxation Techniques

By reducing tension and stress, focusing and relaxation techniques allow a woman in labor to rest and to conserve energy for the task of giving birth. Attention-focusing and distraction techniques are forms of care that are effective to some degree in relieving labor pain (Albers, 2007). ![]() Some women bring a favorite object such as a photograph or stuffed animal to the labor room and focus their attention on this object during contractions. Others choose to fix their attention on some object in the labor room. As the contraction begins, they focus on their chosen object and perform a breathing technique to reduce their perception of pain.

Some women bring a favorite object such as a photograph or stuffed animal to the labor room and focus their attention on this object during contractions. Others choose to fix their attention on some object in the labor room. As the contraction begins, they focus on their chosen object and perform a breathing technique to reduce their perception of pain.

With imagery the woman focuses her attention on a pleasant scene, a place where she feels relaxed, or an activity she enjoys. She can imagine walking through a restful garden or breathing in light, energy, and healing color and breathing out worries and tension. Choosing the subject for the imagery and practicing the technique during pregnancy enhances effectiveness during labor.

During childbirth preparation classes the coach can learn how to palpate a woman’s body to detect tense and contracted muscles. The woman then learns how to relax the tense muscle in response to the gentle stroking of the muscle by the coach (Fig. 17-2). In a common feedback mechanism, the woman and her coach say the word “relax” at the onset of each contraction and throughout it as needed. With practice, the coach can effectively use support, feedback, and touch to facilitate the woman’s relaxation and thereby reduce tension and stress and enhance the progress of labor (Humenick, Schrock, & Libresco, 2000). ![]()

FIG. 17-2 A laboring woman using focusing and breathing techniques during a uterine contraction with coaching from her partner. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

Women may find that drinking herb tea during labor can help them to relax (e.g., chamomile), to reduce nausea (e.g., lemon balm, peppermint), and to enhance energy and reduce fatigue (e.g., ginger, ginseng). ![]() Drinking tea can have the additional benefit of maintaining fluid balance (Walls, 2009).

Drinking tea can have the additional benefit of maintaining fluid balance (Walls, 2009).

The nurse can assist the woman by providing a quiet and relaxed environment, offering cues as needed, and recognizing signs of tension (e.g., frowning, change in tone of voice, clenching of fists). A relaxed environment for labor is created by controlling sensory stimuli (e.g., light, noise, temperature), and reducing interruptions. Nurses should remain calm and unhurried in their approach and sit rather than stand at the bedside whenever possible (Creehan, 2008).

Breathing Techniques

Different approaches to childbirth preparation stress varying breathing techniques to provide distraction, thereby reducing the perception of pain and helping the woman maintain control throughout contractions. In the first stage of labor such breathing techniques can promote relaxation of the abdominal muscles and thereby increase the size of the abdominal cavity. This lessens discomfort generated by friction between the uterus and abdominal wall during contractions. Because the muscles of the genital area also become more relaxed, they do not interfere with fetal descent. In the second stage, breathing is used to increase abdominal pressure and thereby assist in expelling the fetus. Breathing also can be used to relax the pudendal muscles to prevent precipitate expulsion of the fetal head (Fig. 17-3).

FIG. 17-3 Expectant parents learning relaxation techniques. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

For couples who have prepared for labor by practicing relaxing and breathing techniques, a simple review with occasional reminders may be all that is necessary to help them along. For those who have had no preparation, instruction and practice in simple breathing and relaxation techniques can be given early in labor and often is surprisingly successful. Nurses can also model breathing techniques and breathe in synchrony with the woman and her partner. Motivation is high, and readiness to learn is enhanced by the reality of labor.

Various breathing techniques can be used for controlling pain during contractions (Box 17-3). The nurse needs to determine what, if any, techniques the laboring couple knows before giving them instruction. Simple patterns are more easily learned. Paced breathing is most associated with prepared childbirth and includes slow-paced, modified-paced, and patterned-paced breathing (pant-blow) techniques. Each labor is different, and nursing support includes assisting couples to adapt breathing techniques to their individual labor experience.

All patterns begin with a deep, relaxing, cleansing breath to “greet the contraction” and end with another deep breath exhaled to “gently blow the contraction away.” These deep breaths ensure adequate oxygen for mother and baby and signal that a contraction is beginning or has ended. As the breath is exhaled, respiratory and voluntary muscles relax (Creehan, 2008). In general, slow-paced breathing is performed at approximately half the woman’s normal breathing rate and is initiated when she can no longer walk or talk through contractions. The woman should take no fewer than three or four breaths per minute. Slow-paced breathing aids in relaxation and provides optimum oxygenation. The woman should continue to use this technique for as long as it is effective in reducing the perception of pain and maintaining control. As contractions increase in frequency and intensity, the woman often needs to change to a more complex breathing technique, which is shallower and faster than her normal rate of breathing, but should not exceed twice her resting respiratory rate. This modified-paced breathing pattern requires that she remain alert and concentrate more fully on breathing, thus blocking more painful stimuli than the simpler slow-paced breathing pattern (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008 [www.birthsource.com]).

The most difficult time to maintain control during contractions comes during the transition phase of the first stage of labor, when the cervix dilates from 8 cm to 10 cm. Even for the woman who has prepared for labor, concentration on breathing techniques is difficult to maintain. Patterned-paced (pant-blow) breathing is suggested during this phase. It is performed at the same rate as modified-paced breathing and consists of panting breaths combined with soft blowing breaths at regular intervals. The patterns may vary (i.e., pant, pant, pant, pant, blow [4:1 pattern] or pant, pant, pant, blow [3:1 pattern]) (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008). An undesirable reaction to this type of breathing is hyperventilation. The woman and her support person must be aware of and watch for symptoms of the resultant respiratory alkalosis: lightheadedness, dizziness, tingling of the fingers, or circumoral numbness. Respiratory alkalosis may be eliminated by having the woman breathe into a paper bag held tightly around her mouth and nose. This enables her to rebreathe carbon dioxide and replace the bicarbonate ions. The woman also can breathe into her cupped hands if no bag is available. Maintaining a breathing rate that is no more than twice the normal rate will lessen chances of hyperventilation. The partner can help the woman maintain her breathing rate with visual, tactile, or auditory cues.

As the fetal head reaches the pelvic floor, the woman may feel the urge to push and may automatically begin to exert downward pressure by contracting her abdominal muscles. During second-stage pushing, the woman should find a breathing pattern that is relaxing and feels good to her and is safe for her baby. Any regular or rhythmic breathing that avoids prolonged breath holding during pushing should maintain a good oxygen flow to the fetus (Perinatal Education Associates, 2008).

The woman can control the urge to push by taking panting breaths or by slowly exhaling through pursed lips (as though blowing out a candle). This type of breathing can be used to overcome the urge to push when the cervix is not fully prepared (e.g., less than 8 cm dilated, not retracting) and to facilitate a slow birth of the fetal head.

Effleurage and Counterpressure

Effleurage (light massage) and counterpressure have brought relief to many women during the first stage of labor. ![]() The gate-control theory may supply the reason for the effectiveness of these measures. Effleurage is light stroking, usually of the abdomen, in rhythm with breathing during contractions. It is used to distract the woman from contraction pain. Often the presence of monitor belts makes it difficult to perform effleurage on the abdomen; therefore, a thigh or the chest may be used. As labor progresses, hyperesthesia may make effleurage uncomfortable and thus less effective.

The gate-control theory may supply the reason for the effectiveness of these measures. Effleurage is light stroking, usually of the abdomen, in rhythm with breathing during contractions. It is used to distract the woman from contraction pain. Often the presence of monitor belts makes it difficult to perform effleurage on the abdomen; therefore, a thigh or the chest may be used. As labor progresses, hyperesthesia may make effleurage uncomfortable and thus less effective.

Counterpressure is steady pressure applied by a support person to the sacral area with a firm object (e.g., tennis ball) or the fist or heel of the hand. Pressure can also be applied to both hips (double hip squeeze) or to the knees (Creehan, 2008). Application of counterpressure helps the woman cope with the sensations of internal pressure and pain in the lower back. It is especially helpful when back pain is caused by pressure of the occiput against spinal nerves when the fetal head is in a posterior position. Counterpressure lifts the occiput off these nerves, thereby providing pain relief. The support person will need to be relieved occasionally because application of counterpressure is hard work.

Music

Music, recorded or live, can provide a distraction, enhance relaxation, and lift spirits during labor, thereby reducing the woman’s level of stress, anxiety, and perception of pain. It can be used to promote relaxation in early labor and to stimulate movement as labor progresses. Music can help to create a more relaxed atmosphere in the birth room, leading to a more relaxed approach by health care providers (Creehan, 2008; Zwelling, et al., 2006). Women should be encouraged to prepare their musical preferences in advance and to bring a CD player or mP3 player (e.g., iPod) to the hospital or birthing center. They should choose familiar music that is associated with pleasant memories, which can also facilitate the process of guided imagery. Use of a headset or earphones may increase the effectiveness of the music because other sounds will be shut out. Live music provided at the bedside by a support person may be very helpful in transmitting energy that decreases tension and elevates mood. Changing the tempo of the music to coincide with the rate and rhythm of each breathing technique may facilitate proper pacing.![]() Although promising, there is insufficient evidence at the present time to support the effectiveness of music as a method of pain relief during labor. Further research is recommended (Smith, Collins, Cyna, & Crowther, 2006).

Although promising, there is insufficient evidence at the present time to support the effectiveness of music as a method of pain relief during labor. Further research is recommended (Smith, Collins, Cyna, & Crowther, 2006).

Water Therapy (Hydrotherapy)

Bathing, showering, and jet hydrotherapy (whirlpool baths) with warm water (e.g., at or below body temperature) are nonpharmacologic measures that can promote comfort and relaxation during labor ![]() (Fig. 17-4). The warm water stimulates the release of endorphins, relaxes fibers to close the gate on pain, promotes better circulation and oxygenation and helps to soften the perineal tissues. Most women find immersion in water to be soothing, relaxing, and comforting. While immersed, they may find it easier to let go and allow labor to take its course (Gilbert, 2011). Women in labor often report that pain and discomfort subside while in the water (Albers, 2007).

(Fig. 17-4). The warm water stimulates the release of endorphins, relaxes fibers to close the gate on pain, promotes better circulation and oxygenation and helps to soften the perineal tissues. Most women find immersion in water to be soothing, relaxing, and comforting. While immersed, they may find it easier to let go and allow labor to take its course (Gilbert, 2011). Women in labor often report that pain and discomfort subside while in the water (Albers, 2007).

FIG. 17-4 Water therapy during labor. A, Use of shower during labor. B, Woman experiencing back labor relaxes as partner sprays warm water on her back. C, Laboring woman relaxes in Jacuzzi. Note that fetal monitoring can continue during time in the Jacuzzi. (A and B, Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA; C, courtesy Spacelabs Medical, Redmond, WA.)

Prior to initiating hydrotherapy measures, agency policy should be consulted to determine if the approval of the laboring woman’s primary health care provider is required and if criteria need to be met in terms of the status of the maternal and fetal unit (e.g., stable vital signs and fetal heart rate [FHR] and pattern, stage of labor, etc.). In order to reduce the risk of a prolonged labor, hydrotherapy is usually initiated when the woman is in active labor, at approximately 5 cm. It is at this time that she may be getting discouraged and will welcome the change that hydrotherapy offers. Remember to preserve her modesty because she may be shy about the exposure of her body when getting into a tub or shower (Creehan, 2008).

In addition to pain relief and relaxation, hydrotherapy offers other benefits. If a woman is having “back labor” as the result of an occiput posterior or transverse position, assuming a hands-and-knees or a side-lying position in the tub enhances spontaneous fetal rotation to the occiput anterior position as a result of increased buoyancy. Because less effort is needed to change positions while in the water, women are encouraged to assume upright positions and to alter positions more frequently, facilitating the progress of their labors and helping them cope with labor-associated stressors (Stark, Rudell, & Haus, 2008). Additionally, hydrotherapy results in less use of pharmacologic pain relief measures, fewer forceps- or vacuum-assisted births, fewer episiotomies, less perineal trauma, and increased maternal satisfaction with the birth experience (Zwelling et al., 2006) (see Community Activity box.)

When hydrotherapy is in use, FHR monitoring is done by Doppler, fetoscope, or wireless external monitor (see Fig. 17-4, C). Placement of internal electrodes is contraindicated for jet hydrotherapy. Several studies have investigated the risks of using hydrotherapy with ruptured membranes. Findings have shown no increases in chorioamnionitis, postpartum endometritis, neonatal infections, or antibiotic use. However, care must be taken to use tubs that can be cleansed easily and thoroughly. A unit protocol should be developed for cleaning the tubs (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007; Zwelling et al., 2006).

There is no limit to the time women can stay in the bath, and often they are encouraged to stay in it as long as desired. However, most women use jet hydrotherapy for 30 to 60 minutes at a time. During the bath, if the woman’s temperature and the FHR increase, if the labor process becomes less effective (e.g., slows or becomes too intense), or if relief of pain is reduced, the woman can come out of the bath and return at a later time. Repeated baths with occasional breaks may be more effective in relieving pain in long labors than extended amounts of time in the water. The temperature of the water should be maintained at 36° to 37° C with the water covering the woman’s abdomen to gain maximum effect from the hydrostatic pressure and buoyancy of the water. Her shoulders should remain out of the water to facilitate the dissipation of heat (Creehan, 2008).

Using a shower provides comfort through the application of heat as the handheld shower head is directed to areas of discomfort (see Fig. 17-4, A and B). The coach or partner can participate in this comfort measure by holding and directing the shower head.

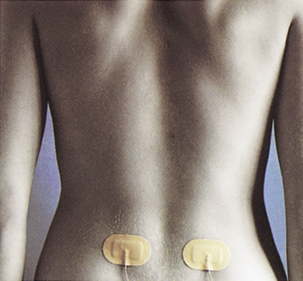

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) involves the placing of two pairs of flat electrodes on either side of the woman’s thoracic and sacral spine (Fig. 17-5). These electrodes provide continuous low-intensity electrical impulses or stimuli from a battery-operated device. ![]() During a contraction the woman increases the stimulation from low to high intensity by turning control knobs on the device. High intensity should be maintained for at least 1 minute to facilitate release of endorphins. Women describe the resulting sensation as a tingling or buzzing. TENS is most useful for lower back pain during the early first stage of labor. Women tend to rate the device as helpful although its use does not decrease pain. It appears that the electrical impulses or stimuli somehow make the pain less disturbing. There are no serious safety concerns associated with the use of TENS (Hawkins, Goetzl, & Chestnut, 2007).

During a contraction the woman increases the stimulation from low to high intensity by turning control knobs on the device. High intensity should be maintained for at least 1 minute to facilitate release of endorphins. Women describe the resulting sensation as a tingling or buzzing. TENS is most useful for lower back pain during the early first stage of labor. Women tend to rate the device as helpful although its use does not decrease pain. It appears that the electrical impulses or stimuli somehow make the pain less disturbing. There are no serious safety concerns associated with the use of TENS (Hawkins, Goetzl, & Chestnut, 2007).

Acupressure and Acupuncture

Acupressure and acupuncture can be used in pregnancy, in labor, and postpartum to relieve pain and other discomforts. Pressure, heat, or cold is applied to acupuncture points called tsubos. ![]() These points have an increased density of neuroreceptors and increased electrical conductivity. Acupressure is said to promote circulation of blood, the harmony of yin and yang, and the secretion of neurotransmitters, thus maintaining normal body functions and enhancing well-being (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Acupressure is best applied over the skin without using lubricants. Pressure is usually applied with the heel of the hand, fist, or pads of the thumbs and fingers (Fig. 17-6). Tennis balls or other devices also may be used. Pressure is applied with contractions initially and then continuously as labor progresses to the transition phase at the end of the first stage of labor (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau). Synchronized breathing by the caregiver and the woman is suggested for greater effectiveness. Acupressure points are found on the neck, the shoulders, the wrists, the lower back including sacral points, the hips, the area below the kneecaps, the ankles, the nails on the small toes, and the soles of the feet.

These points have an increased density of neuroreceptors and increased electrical conductivity. Acupressure is said to promote circulation of blood, the harmony of yin and yang, and the secretion of neurotransmitters, thus maintaining normal body functions and enhancing well-being (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Acupressure is best applied over the skin without using lubricants. Pressure is usually applied with the heel of the hand, fist, or pads of the thumbs and fingers (Fig. 17-6). Tennis balls or other devices also may be used. Pressure is applied with contractions initially and then continuously as labor progresses to the transition phase at the end of the first stage of labor (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau). Synchronized breathing by the caregiver and the woman is suggested for greater effectiveness. Acupressure points are found on the neck, the shoulders, the wrists, the lower back including sacral points, the hips, the area below the kneecaps, the ankles, the nails on the small toes, and the soles of the feet.

FIG. 17-6 Ho-Ku acupressure point (back of hand where thumb and index finger come together) used to enhance uterine contractions without increasing pain. (Courtesy Julie Perry Nelson, Loveland, CO.)

Acupuncture is the insertion of fine needles into specific areas of the body to restore the flow of qi (energy) and to decrease pain, which is thought to be obstructing the flow of energy. Effectiveness may be attributed to the alteration of chemical neurotransmitter levels in the body or to the release of endorphins as a result of hypothalamic activation. Acupuncture should be done by a trained certified therapist. Current evidence indicates that acupuncture may be beneficial for relief of labor pain; however, further study is indicated (Hawkins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2006; Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).![]()

Application of Heat and Cold

Warmed blankets, warm compresses, heated rice bags, a warm bath or shower, or a moist heating pad can enhance relaxation and reduce pain during labor. ![]() Heat relieves muscle ischemia and increases blood flow to the area of discomfort. Heat application is effective for back pain caused by a posterior presentation or general backache from fatigue.

Heat relieves muscle ischemia and increases blood flow to the area of discomfort. Heat application is effective for back pain caused by a posterior presentation or general backache from fatigue.

Cold application such as cold cloths, frozen gel packs, or ice packs applied to the back, the chest, and/or the face during labor may be effective in increasing comfort when the woman feels warm. They also may be applied to areas of musculoskeletal pain. Cooling relieves pain by reducing the muscle temperature and relieving muscle spasms (Creehan, 2008). A woman’s culture may make the use of cold during labor unacceptable, however.

Heat and cold may be used alternately for a greater effect. Neither heat nor cold should be applied over ischemic or anesthetized areas because tissues can be damaged. One or two layers of cloth should be placed between the skin and a hot or cold pack to prevent damage to the underlying integument.

Touch and Massage

Touch and massage have been an integral part of the traditional care process for women in labor. ![]() A variety of massage techniques have been shown to be safe and effective during labor (Gilbert, 2011; Zwelling et al., 2006).

A variety of massage techniques have been shown to be safe and effective during labor (Gilbert, 2011; Zwelling et al., 2006).

Touch can be as simple as holding the woman’s hand, stroking her body, and embracing her. When using touch to communicate caring, reassurance, and concern, it is important that the woman’s preferences for touch (e.g., who can touch her, where they can touch her, and how they can touch her) and responses to touch be determined. A woman with a history of sexual abuse or certain cultural beliefs may be uncomfortable with touch. Women who perceive touch during labor as positive have less pain, anxiety, and need for pain medication (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Touch also can involve very specialized techniques that require manipulation of the human energy field.

Therapeutic touch (TT) uses the concept of energy fields within the body called prana. Prana are thought to be deficient in some people who are in pain. TT uses laying-on of hands by a specially trained person to redirect energy fields associated with pain. Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of TT to enhance relaxation, reduce anxiety, and relieve pain (Aghabati, Mohammadi, & Pour Esmaiel, 2010); however, little is known about the use or effectiveness of TT for relieving labor pain. ![]()

Head, hand, back, and foot massage may be very effective in reducing tension and enhancing comfort. Hand and foot massage may be especially relaxing in advanced labor when hyperesthesia limits a woman’s tolerance for touch on other parts of her body. Combining massage with aromatherapy oil or lotion enhances relaxation both during and between contractions. The woman and her partner should be encouraged to experiment with different types of massage during pregnancy to determine what might feel best and be most relaxing during labor.

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is a form of deep relaxation, similar to daydreaming or meditation (see www.hypnobirthing.com). ![]() While under hypnosis women are in a state of focused concentration and the subconscious mind can be more easily accessed. Hypnosis techniques used for labor and birth place an emphasis on enhancing relaxation and diminishing fear, anxiety, and perception of pain. Current evidence suggests that hypnosis seems to reduce fear, tension, and pain during labor and to raise the pain threshold. Women using this technique report a greater sense of control over painful contractions and a higher level of satisfaction with their childbirth experience. Because it reduces the need for pain medication, hypnosis can be helpful when used with other interventions during labor. A few negative effects of hypnosis have been reported, including mild dizziness, nausea, and headache. These negative effects seem to be associated with failure to dehypnotize the woman properly (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

While under hypnosis women are in a state of focused concentration and the subconscious mind can be more easily accessed. Hypnosis techniques used for labor and birth place an emphasis on enhancing relaxation and diminishing fear, anxiety, and perception of pain. Current evidence suggests that hypnosis seems to reduce fear, tension, and pain during labor and to raise the pain threshold. Women using this technique report a greater sense of control over painful contractions and a higher level of satisfaction with their childbirth experience. Because it reduces the need for pain medication, hypnosis can be helpful when used with other interventions during labor. A few negative effects of hypnosis have been reported, including mild dizziness, nausea, and headache. These negative effects seem to be associated with failure to dehypnotize the woman properly (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Biofeedback

Biofeedback may provide another relaxation technique that can be used for labor. ![]() Biofeedback is based on the theory that if a person can recognize physical signals, certain internal physiologic events can be changed (i.e., whatever signs the woman has that are associated with her pain). For biofeedback to be effective, the woman must be educated during the prenatal period to become aware of her body and its responses and how to relax. The woman must learn how to use thinking and mental processes (e.g., focusing) to control body responses and functions. Informational biofeedback helps couples develop awareness of their bodies and use strategies to change their responses to stress. If the woman responds to pain during a contraction with tightening of muscles, frowning, moaning, and breath holding, her partner uses verbal and touch feedback to help her relax. Formal biofeedback, which uses machines to detect skin temperature, blood flow, or muscle tension, also can prepare women to intensify their relaxation responses. Biofeedback-assisted relaxation techniques are not always successful in reducing labor pain. Using these techniques effectively requires the strong support of caregivers (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Biofeedback is based on the theory that if a person can recognize physical signals, certain internal physiologic events can be changed (i.e., whatever signs the woman has that are associated with her pain). For biofeedback to be effective, the woman must be educated during the prenatal period to become aware of her body and its responses and how to relax. The woman must learn how to use thinking and mental processes (e.g., focusing) to control body responses and functions. Informational biofeedback helps couples develop awareness of their bodies and use strategies to change their responses to stress. If the woman responds to pain during a contraction with tightening of muscles, frowning, moaning, and breath holding, her partner uses verbal and touch feedback to help her relax. Formal biofeedback, which uses machines to detect skin temperature, blood flow, or muscle tension, also can prepare women to intensify their relaxation responses. Biofeedback-assisted relaxation techniques are not always successful in reducing labor pain. Using these techniques effectively requires the strong support of caregivers (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy uses oils distilled from plants, flowers, herbs, and trees to promote health and to treat and balance the mind, body, and spirit. ![]() These essential oils are highly concentrated, complex essences, and are mixed with lotions or creams before they are applied to the skin (e.g., for a back massage). Certain essential oils can tone the uterus, encourage contractions, reduce pain, relieve tension, diminish fear and anxiety, and enhance the feeling of well-being. Lavender, rose, and jasmine oils can promote relaxation and reduce pain. Rose oil also acts as an antidepressant and uterine tonic, while jasmine oil strengthens contractions and decreases feelings of panic in addition to reducing pain. Essential oils of bergamot or rosemary can be diffused or used in a massage oil to relieve exhaustion (Gilbert, 2011; Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007; Walls, 2009). Oils may also be used by adding a few drops to a warm bath, to warm water used for soaking compresses that can be applied to the body, or to an aromatherapy lamp to vaporize a room. Drops of essential oils can be put on a pillow or on a woman’s brow or palms, or used as an ingredient in creating massage oil (Simkin & Bolding, 2004; Walls; Zwelling et al., 2006). Certain odors or scents can evoke pleasant memories and feelings of love and security. As a result, it would be helpful for a woman to choose the scents that she will use (Trout, 2004). Currently there is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of aromatherapy for pain relief in labor although its use has elicited promising results (Berghella et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2006; Zwelling et al.).

These essential oils are highly concentrated, complex essences, and are mixed with lotions or creams before they are applied to the skin (e.g., for a back massage). Certain essential oils can tone the uterus, encourage contractions, reduce pain, relieve tension, diminish fear and anxiety, and enhance the feeling of well-being. Lavender, rose, and jasmine oils can promote relaxation and reduce pain. Rose oil also acts as an antidepressant and uterine tonic, while jasmine oil strengthens contractions and decreases feelings of panic in addition to reducing pain. Essential oils of bergamot or rosemary can be diffused or used in a massage oil to relieve exhaustion (Gilbert, 2011; Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007; Walls, 2009). Oils may also be used by adding a few drops to a warm bath, to warm water used for soaking compresses that can be applied to the body, or to an aromatherapy lamp to vaporize a room. Drops of essential oils can be put on a pillow or on a woman’s brow or palms, or used as an ingredient in creating massage oil (Simkin & Bolding, 2004; Walls; Zwelling et al., 2006). Certain odors or scents can evoke pleasant memories and feelings of love and security. As a result, it would be helpful for a woman to choose the scents that she will use (Trout, 2004). Currently there is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of aromatherapy for pain relief in labor although its use has elicited promising results (Berghella et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2006; Zwelling et al.).

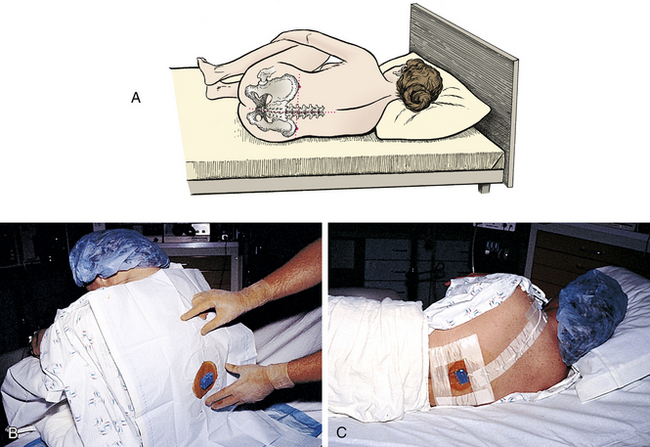

Intradermal Water Block

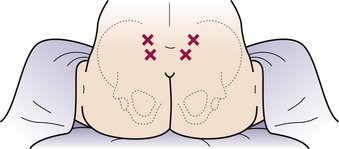

An intradermal water block involves the injection of small amounts of sterile water (e.g., 0.05 to 0.1 ml) by using a fine needle (e.g., 25 gauge) into four locations on the lower back to relieve low back pain (Fig. 17-7). It is a simple procedure that can be performed by the nurse and is effective in early labor and in an effort to delay the initiation of pharmacologic pain relief measures (Hawkins et al., 2007). Intense stinging will occur for about 20 to 30 seconds after injection, but relief of back pain for up to 2 hours has been reported. The procedure can be repeated although the woman may find that the stinging that occurs with administration creates too much discomfort (Creehan, 2008). Effectiveness of this method is probably related to the mechanisms of counterirritation (i.e., reducing localized pain in one area by irritating the skin in an area nearby), gate control, or an increase in the level of endogenous opioids (endorphins). When the effect wears off, the treatment can be repeated, or another method of pain relief can be used (Fogarty, 2008; Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007).

FIG. 17-7 Intradermal injections of 0.1 ml of sterile water in the treatment of women with back pain during labor. Sterile water is injected into four locations on the lower back, two over each posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and two 3 cm below and 1 cm medial to the PSIS. The injections should raise a bleb on the skin. Simultaneous injections administered by two clinicians will decrease the pain of the injections. (Source: Leeman, L., Fontaine, P., King, V., Klein, M., & Ratcliffe, S. [2003]. The nature and management of labor pain: Part I. Nonpharmacologic pain relief. American Family Physician 68[6], 1109-1112.)

Pharmacologic Pain Management

Pharmacologic measures for pain management should be implemented before pain becomes so severe that catecholamines increase and labor is prolonged. It is unacceptable for women in labor to endure severe pain when safe and effective relief measures are available (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2004). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic measures, when used together, increase the level of pain relief and create a more positive labor experience for the woman and her family. Nonpharmacologic measures can be used for relaxation and pain relief, especially in early labor. Pharmacologic measures can be implemented as labor becomes more active and discomfort and pain intensify. Less pharmacologic intervention often is required because nonpharmacologic measures enhance relaxation and potentiate the analgesic effect. However, women are increasingly using pharmacologic measures, especially epidural analgesia, to relieve their pain during labor and birth.

Sedatives

Sedatives relieve anxiety and induce sleep. They may be given to a woman experiencing a prolonged latent phase of labor when there is a need to decrease anxiety or promote sleep. They may also be given to augment analgesics and reduce nausea when an opioid is used.

Barbiturates such as secobarbital sodium (Seconal) can cause undesirable side effects including respiratory and vasomotor depression affecting the woman and newborn. Because of the potential for neonatal central nervous system (CNS) depression, barbiturates should be avoided if birth is anticipated within 12 to 24 hours. The depressant effects are increased if a barbiturate is administered with another CNS depressant such as an opioid analgesic. However, pain will be magnified if a barbiturate is given without an analgesic to women experiencing pain because normal coping mechanisms may be blunted. As a result of these disadvantages, barbiturates are seldom used during labor (Creehan, 2008; Hawkins et al., 2007).

Phenothiazines (e.g., promethazine [Phenergan], hydroxyzine [Vistaril]) do not relieve pain but are often given with opioids to decrease anxiety and apprehension, increase sedation, and reduce nausea and vomiting. Promethazine is probably the most widely used drug in this class. It causes significant sedation and has been shown to impair the analgesic efficacy of opioids. Using opioids with less potential to cause nausea and vomiting should make the routine use of promethazine unnecessary. Metoclopramide (Reglan) is an antiemetic that causes little sedation and may potentiate the effects of analgesics, Ondansetron (Zofran) is another very effective antiemetic that has few side effects. Whenever possible, it should be used instead of promethazine (Hawkins et al., 2007).

Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam [Valium], lorazepam [Ativan]), when given with an opioid analgesic, seem to enhance pain relief and reduce nausea and vomiting. Because benzodiazepines cause significant maternal amnesia, however, their use should be avoided during labor. A major disadvantage of diazepam is that it disrupts thermoregulation in newborns, making them less able to maintain body temperature (Hawkins et al., 2007).

Analgesia and Anesthesia

The use of analgesia and anesthesia was not generally accepted as part of obstetric management until Queen Victoria used chloroform during the birth of her son in 1853. Since then much study has gone into the development of pharmacologic measures for controlling discomfort during the birth period. The goal of researchers is to develop methods that will provide adequate pain relief to women without increasing maternal or fetal risk or affecting the progress of labor.

Nursing management of obstetric analgesia and anesthesia combines the nurse’s expertise in maternity care with a knowledge and understanding of anatomy and physiology and of medications and their therapeutic effects, adverse reactions, and methods of administration.

Anesthesia encompasses analgesia, amnesia, relaxation, and reflex activity. Anesthesia abolishes pain perception by interrupting the nerve impulses to the brain. The loss of sensation may be partial or complete, sometimes with the loss of consciousness.

The term analgesia refers to the alleviation of the sensation of pain or the raising of the threshold for pain perception without loss of consciousness.

The type of analgesic or anesthetic chosen is determined in part by the stage of labor of the woman and by the method of birth planned (Box 17-4).

Systemic Analgesia

Use of systemic analgesia for relieving the pain of labor has been declining, although it still remains the major pharmacologic method for relieving the pain of labor when personnel trained in regional analgesia (e.g., epidural analgesia) are not available (Bucklin, Hawkins, Anderson, & Ullrich, 2005). Systemic analgesics cross the maternal blood-brain barrier to provide central analgesic effects. They also cross the placenta. Once transferred to the fetus, analgesics cross the fetal blood-brain barrier more readily than the maternal blood-brain barrier. The duration of action also will be longer because the systemic analgesics used during labor have a significantly longer half-life in the fetus and newborn. Effects on the fetus and newborn can be profound (e.g., respiratory depression, decreased alertness, delayed sucking), depending on the characteristics of the specific systemic analgesic used, the dosage given, and the route and timing of administration. Intravenous (IV) administration is preferred to intramuscular (IM) administration because the medication’s onset of action is faster and more predictable; as a result, a higher level of pain relief usually occurs with smaller doses. IV patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is available for use during labor. With this method, the woman self-administers small doses of an opioid analgesic by using a pump programmed for dose and frequency. Overall, a lower total amount of analgesic is used, and women appreciate the sense of autonomy provided by this method of pain relief (Hawkins et al., 2007).

Classifications of analgesic drugs used to relieve the pain of childbirth include opioid (narcotic) agonists and opioid (narcotic) agonist-antagonists. Choice of which medication to use often depends on the primary health care provider’s preferences and the characteristics of the laboring woman. The type of systemic analgesics used therefore often varies among obstetric units.

Opioid Agonist Analgesics: Opioid (narcotic) agonist analgesics such as hydromorphone hydrochloride (Dilaudid), meperidine (Demerol), fentanyl (Sublimaze), and sufentanil citrate (Sufenta) are effective for relieving severe, persistent, or recurrent pain by blunting the perception of pain, though not eliminating it completely. As pure opioid agonists they stimulate major opioid receptors, mu and kappa. They have no amnesic effect but create a feeling of well-being or euphoria and enhance a woman’s ability to rest between contractions. Because opioids can inhibit uterine contractions, they should not be administered until labor is well established unless they are being used to enhance therapeutic rest during a prolonged latent phase of labor (Creehan, 2008). These analgesics decrease gastric emptying and increase nausea and vomiting. Bladder and bowel elimination can be inhibited. Because heart rate (e.g., bradycardia, tachycardia), blood pressure (e.g., hypotension), and respiratory effort (e.g., depression) can be adversely affected, opioid analgesics should be used cautiously in women with respiratory and cardiovascular disorders. Safety precautions should be taken because sedation and dizziness can occur after administration, increasing the risk for injury.

Hydromorphone hydrochloride (Dilaudid) is a potent opioid agonist analgesic that can be administered by IV or IM route during labor. After IV administration the onset of action occurs within 10 to 15 minutes, the peak effect is reached in 15 to 30 minutes, and the duration of action is approximately 2 to 3 hours. IM administration has an onset of action in 15 minutes, with a peak in 30 to 60 minutes and a duration of action of approximately 4 to 5 hours.

Meperidine hydrochloride (Demerol) used to be the most commonly used opioid agonist analgesic for women in labor, but is no longer the preferred choice because other medications have fewer side effects. In particular, the accumulation of normeperidine, a toxic metabolite of meperidine, causes prolonged neonatal sedation and neurobehavioral changes that are evident for the first 2 to 3 days of life (Hawkins et al., 2007). When it is used, the onset of action after IV administration is almost immediate and the duration of action is approximately 1.5 to 2 hours. The onset of action begins in 10 to 20 minutes after an IM injection of meperidine and the duration is 2 to 3 hours (Hawkins et al.).

Fentanyl citrate (Sublimaze) and sufentanil citrate (Sufenta) are potent short-acting opioid agonist analgesics. Sufentanil use is increasing because it has a more potent analgesic action than fentanyl when given through an epidural catheter. Also less sufentanil will cross the placenta, resulting in reduced fetal exposure. Onset of action after IV injection occurs within 2 to 5 minutes, the action peaks in 3 to 5 minutes, and the duration of action is approximately 30 to 60 minutes. Onset of the medication action occurs in 7 to 8 minutes after IM injection, reaches its peak effect in 20 to 30 minutes, and lasts for 1 to 2 hours. More frequent dosing is required with fentanyl and sufentanil because of their relatively short duration of action (Hawkins et al., 2007). As a result, these opioids are most commonly administered intrathecally or epidurally, alone or in combination with a local anesthetic agent (e.g., bupivacaine [Marcaine]) (see the Medication Guide: Opioid Agonist Analgesics).

Ideally, birth should occur less than 1 hour or more than 4 hours after administration of an opioid agonist analgesic so that neonatal CNS depression resulting from the opioid is minimized.

Opioid (Narcotic) Agonist-Antagonist Analgesics: An agonist is an agent that activates or stimulates a receptor to act; an antagonist is an agent that blocks a receptor or a medication

designed to activate a receptor. Opioid (narcotic) agonist-antagonist analgesics such as butorphanol (Stadol) and nalbuphine (Nubain) are agonists at kappa opioid receptors and are either antagonists or weak agonists at mu opioid receptors. In the doses used during labor, these mixed opioids provide adequate analgesia without causing significant respiratory depression in the mother or neonate. They are less likely to cause nausea and vomiting, but sedation may be as great or greater when compared with pure opioid agonists. As a result of these effects, parenteral opioid agonist-antagonist analgesics are used more commonly during labor than the opioid agonist analgesics. Intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intravenous routes of administration can be used, but the IV route is preferred. This classification of opioid analgesics, especially nalbuphine, is not suitable for women with an opioid dependence because the antagonist activity could precipitate withdrawal symptoms (abstinence syndrome) in both the mother and her newborn (Hawkins et al., 2007) (see the Medication Guide: Opioid Agonist-Antagonist Analgesics and Signs of Potential Complications box: Maternal Opioid Abstinence Syndrome).

Opioid (Narcotic) Antagonists: Opioids such as hydromorphone, meperidine, and fentanyl can cause excessive CNS depression in the mother, the newborn, or both, although the current practice of giving lower doses of opioids intravenously has reduced the incidence and severity of opioid-induced CNS depression. Opioid (narcotic) antagonists such as naloxone (Narcan) can promptly reverse the CNS depressant effects, especially respiratory depression. In addition, the antagonist counters the effect of the stress-induced levels of endorphins. An opioid antagonist is especially valuable if labor is more rapid than expected and birth is anticipated when the opioid is at its peak effect. The antagonist may be given through an IV line, or it can be administered intramuscularly (see the Medication Guide: Opioid Antagonist). The woman should be told that the pain that was relieved with the use of the opioid analgesic will return with the administration of the opioid antagonist.

An opioid antagonist can be given to the newborn as one part of the treatment for neonatal narcosis, which is a state of CNS depression in the newborn produced by an opioid. Prophylactic administration of naloxone is controversial. Affected infants may exhibit respiratory depression, hypotonia, lethargy, and a delay in temperature regulation. Risk for hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis increases if neonatal narcosis is not treated promptly. Treatment involves ventilation, administration of oxygen, and gentle stimulation. Naloxone is administered, if still required, to reverse CNS depression. More than one dose of naloxone may be required because its half-life is shorter than the half-life of opioids. Alterations in neurologic and behavioral responses may be evident in the newborn for as long as 2 to 4 days after birth. The significance of these neurobehavioral changes is unknown (Hawkins et al., 2007)

Nerve Block Analgesia and Anesthesia

A variety of local anesthetic agents are used in obstetrics to produce regional analgesia (some pain relief and motor block) and anesthesia (complete pain relief and motor block). Most of these agents are related chemically to cocaine and end with the suffix -caine. This helps to identify a local anesthetic.

The principal pharmacologic effect of local anesthetics is the temporary interruption of the conduction of nerve impulses, notably pain. Examples of common agents given are bupivacaine (Marcaine), chloroprocaine (Nesacaine), lidocaine (Xylocaine), ropivacaine (Naropin), and mepivacaine (Carbocaine). Rarely, people are sensitive (allergic) to one or more local anesthetics. Such a reaction may include respiratory depression, hypotension, and other serious adverse effects. Epinephrine, antihistamines, oxygen, and supportive measures should reverse these effects. Sensitivity may be identified by administering minute amounts of the drug to test for an allergic reaction.

Local Perineal Infiltration Anesthesia: Local perineal infiltration anesthesia may be used when an episiotomy is to be performed or when lacerations must be sutured after birth in a woman who does not have regional anesthesia. Rapid anesthesia is produced by injecting approximately 10 to 20 ml of 1% lidocaine or 2% chloroprocaine into the skin and then subcutaneously into the region to be anesthetized. Epinephrine often is added to the solution to localize and intensify the effect of the anesthesia in a region and to prevent excessive bleeding and systemic absorption by constricting local blood vessels. Injections can be repeated to keep the woman comfortable while postbirth repairs are completed.

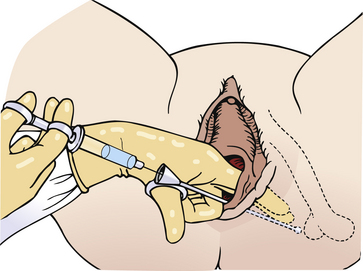

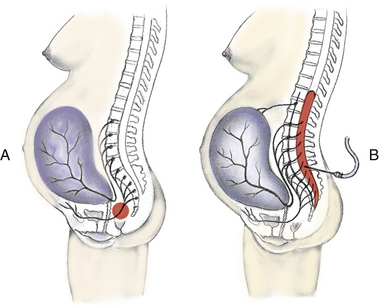

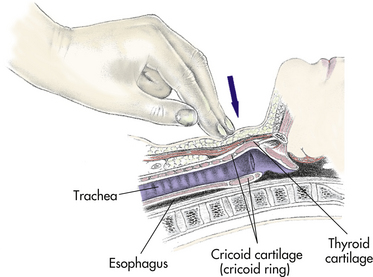

Pudendal Nerve Block: Pudendal nerve block, administered late in the second stage of labor, is useful if an episiotomy is to be performed or if forceps or a vacuum extractor are to be used to facilitate birth. It can also be administered during the third stage of labor if an episiotomy or lacerations must be repaired (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] & ACOG, 2007). A pudendal nerve block is considered to be reasonably effective for pain relief, simple to perform, and very safe (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, Hauth, Rouse, & Spong, 2010; Hawkins et al., 2007). Although a pudendal nerve block does not relieve the pain from uterine contractions, it does relieve pain in the lower vagina, the vulva, and the perineum (Fig. 17-8, A). A pudendal nerve block should be administered 10 to 20 minutes before perineal anesthesia is needed.

FIG. 17-8 Pain pathways and sites of pharmacologic nerve blocks. A, Pudendal nerve block: suitable during second and third stages of labor and for repair of episiotomy or lacerations. B, Epidural block: suitable for all stages of labor and types of birth, and for repair of episiotomy and lacerations.

The pudendal nerve traverses the sacrosciatic notch just medial to the tip of the ischial spine on each side. Injection of an anesthetic solution at or near these points anesthetizes the pudendal nerves peripherally (Fig. 17-9). The transvaginal approach is generally used because it is less painful for the woman, has a higher rate of success in blocking pain, and tends to cause fewer fetal complications (Hawkins et al., 2007). Pudendal block does not change maternal hemodynamic or respiratory functions, vital signs, or the FHR. However, the bearing-down reflex is lessened or lost completely.

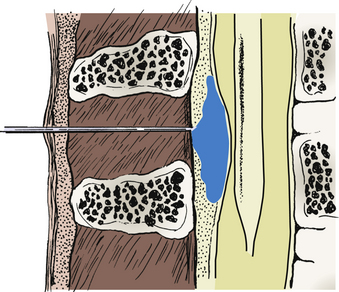

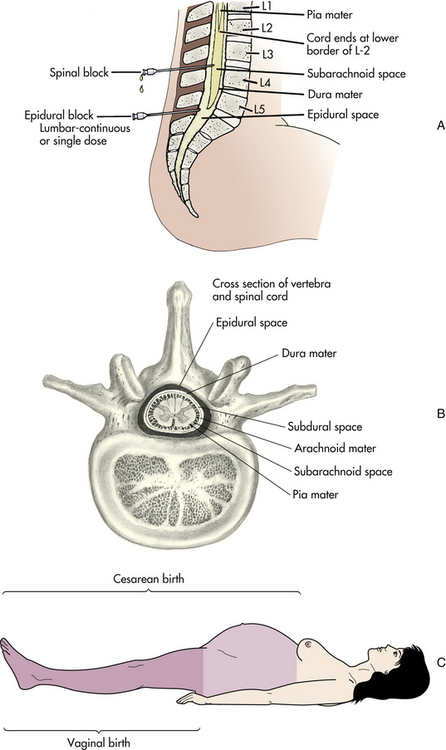

Spinal Anesthesia: In spinal anesthesia (block), an anesthetic solution containing a local anesthetic alone or in combination with an opioid agonist analgesic is injected through the third, fourth, or fifth lumbar interspace into the subarachnoid space (Fig. 17-10, A and B), where the anesthetic solution mixes with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The use of this technique has increased for both elective and emergent cesarean births and is more common than epidural anesthesia for these types of births (Bucklin et al., 2005). Low spinal anesthesia (block) may be used for vaginal birth, but it is not suitable for labor. Spinal anesthesia (block) used for cesarean birth provides anesthesia from the nipple (T6) to the feet. If it is used for vaginal birth, the anesthesia level is from the hips (T10) to the feet (see Fig. 17-10, C).

FIG. 17-10 A, Membranes and spaces of spinal cord and levels of sacral, lumbar, and thoracic nerves. B, Cross section of vertebra and spinal cord. C, Level of anesthesia necessary for cesarean birth and for vaginal births.

For spinal anesthesia (block), the woman sits or lies on her side (e.g., modified Sims position) with back curved to widen the intervertebral space to facilitate insertion of a small-gauge spinal needle and injection of the anesthetic solution into the spinal canal. The nurse supports the woman and encourages her to use breathing and relaxation techniques because she must remain still during the placement of the spinal needle. The needle is inserted and the anesthetic injected between contractions. After the anesthetic solution has been injected, the woman may be positioned upright to allow the heavier (hyperbaric) anesthetic solution to flow downward to obtain the lower level of anesthesia suitable for a vaginal birth. To obtain the higher level of anesthesia desired for cesarean birth she will be positioned supine with head and shoulders slightly elevated. In order to prevent supine hypotensive syndrome, the uterus is displaced laterally by tilting the operating table or placing a wedge under one of her hips. Usually the level of the block will be complete and fixed within 5 to 10 minutes after the anesthetic solution is injected but it can continue to creep upward for 20 minutes or longer. The anesthetic effect will last 1 to 3 hours, depending on the type of agent used (Hawkins et al., 2007) (Fig. 17-11).

Marked hypotension, impaired placental perfusion, and an ineffective breathing pattern may occur during spinal anesthesia. Before induction of the spinal anesthetic, maternal vital signs are assessed and a 20- to 30-minute EFM strip is obtained and evaluated. In addition, the woman’s fluid balance is assessed. A bolus of IV fluid (usually 500 to 1000 ml of lactated Ringer’s or normal saline solution) may be administered 15 to 30 minutes prior to induction of the anesthetic to decrease the potential for hypotension caused by sympathetic blockade (vasodilation with pooling of blood in the lower extremities decreases cardiac output). Although the practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (2007) state that this preanesthetic fluid bolus is not required, it is still usually administered in most clinical settings.

After induction of the anesthetic, maternal blood pressure, pulse, and respirations and fetal heart rate and pattern must be checked and documented every 5 to 10 minutes. If signs of serious maternal hypotension (e.g., a drop in systolic blood pressure to 100 mm Hg or less or below 20% of the baseline blood pressure) or fetal distress (e.g., bradycardia, minimal or absent variability, late decelerations) develop, emergency care must be given (Creehan, 2008) (see the Emergency box: Maternal Hypotension with Decreased Placental Perfusion).

Because the woman is unable to sense her contractions, she must be instructed when to bear down during a vaginal birth. Use of a combination of local anesthetic agent and an opioid reduces the degree of motor function loss, enhancing a woman’s ability to push effectively. If the birth occurs in a delivery room (rather than a labor-delivery-recovery room), the woman will need assistance in the transfer to a recovery bed after expulsion of the placenta and perineal repair if required.

Advantages of spinal anesthesia include ease of administration and absence of fetal hypoxia with maintenance of maternal blood pressure within a normal range. Maternal consciousness is maintained, excellent muscular relaxation is achieved, and blood loss is not excessive.

Disadvantages of spinal anesthesia include possible medication reactions (e.g., allergy), hypotension, and an ineffective breathing pattern; cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be needed. When a spinal anesthetic is given, the need for operative birth (e.g., episiotomy, forceps-assisted birth, or vacuum-assisted birth) tends to increase because voluntary expulsive efforts are reduced or eliminated. After birth, the incidence of bladder and uterine atony, as well as postdural puncture headache, is higher.

Leakage of CSF from the site of puncture of the dura mater (membranous covering of the spinal cord) is thought to be the major causative factor in postdural puncture headache (PDPH), commonly referred to as a spinal headache. Spinal headache is much more likely to occur when the dura is accidentally punctured during the process of administering an epidural block. The needle used for an epidural block has a much larger gauge than the one used for spinal anesthesia and thus creates a bigger opening in the dura, resulting in a greater loss of CSF. Presumably postural changes cause the diminished volume of CSF to exert traction on pain-sensitive CNS structures. Characteristically, assuming an upright position triggers or intensifies the headache, whereas assuming a supine position achieves relief (Hawkins et al., 2007). The resulting headache, auditory problems (e.g., tinnitus) and visual problems (e.g., blurred vision, photophobia) begin within 2 days of the puncture and may persist for days or weeks.