Nursing Care of the Family During Labor and Birth

• Review the factors included in the initial assessment of the woman in labor.

• Describe the ongoing assessment of maternal progress during the first, second, third, and fourth stages of labor.

• Recognize the physical and psychosocial findings indicative of maternal progress during labor.

• Describe fetal assessment during labor.

• Identify signs of developing complications during labor and birth.

• Incorporate evidence-based nursing interventions into a comprehensive plan of care relevant to each stage of labor.

• Recognize the importance of support (family, partner, doula, nurse) in fostering maternal confidence and facilitating the progress of labor and birth.

• Analyze the influence of cultural and religious beliefs and practices on the process of labor and birth.

• Describe the role and responsibilities of the nurse during emergency childbirth.

• Evaluate the effect of perineal trauma on the woman’s reproductive and sexual health.

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

Animation

Audio Glossary

Case Studies

NCLEX Review Questions

Video—Assessment

Video—Childbirth

Video—Nursing Skills

The labor process is an exciting and anxious time for the woman and her significant others (support persons, family). In a relatively short period they experience one of the most profound changes in their lives.

For most women labor begins with the first uterine contraction, continues with hours of hard work during cervical dilation and birth, and ends as the woman begins to recover physically from birth and she and her significant others begin the attachment process with the newborn. Nursing care management focuses on assessment and support of the woman and her significant others throughout labor and birth, with the goal of ensuring the best possible outcome for all involved.

A woman often has lingering impressions of her childbirth experience. Satisfaction with childbirth hinges on her ability to maintain a sense of control. Caregivers who encourage a woman to be actively involved in decision making and who are respectful, supportive, protective, patient, and calm help the woman to remember her childbirth experience in positive terms. Other factors cited by women as influencing their satisfaction with their childbirth experience include degree of awareness of what is occurring, support from their partner, being together with their baby immediately after birth, type of birth (e.g., vaginal or emergency cesarean birth), and degree to which expectations were met and pain was managed (Bryanton, Gagnon, Johnston, & Hatem, 2008). A satisfactory view of childbirth contributes to a woman’s self-esteem and sense of accomplishment with her performance. Adaptation to her role as a mother may also be enhanced.

Frustrations a woman feels regarding her childbirth experience generally stem from factors such as unmet expectations, poorly managed pain, loss of control, lack of knowledge, or the negative behaviors of some caregivers. A woman who perceives her childbirth to be unsatisfactory or traumatic could be at risk for postpartum depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), low self-esteem, impaired attachment with the newborn, and fear leading to no further pregnancies or cesarean birth for a subsequent pregnancy (Bryanton et al., 2008). It is critical that nurses recognize the factors that influence maternal satisfaction as they plan care for women and their families during childbirth.

First Stage of Labor

The first stage of labor begins with the onset of regular uterine contractions and ends with full cervical effacement and dilation. The first stage of labor consists of three phases: the latent phase (through 3 cm of dilation), the active phase (4 to 7 cm of dilation), and the transition phase (8 to 10 cm of dilation). Most nulliparous women seek admission to the hospital in the latent phase because they have not experienced labor before and are unsure of the “right” time to come in. Multiparous women usually do not come to the hospital until they are in the active phase of the first stage of labor. Even though no two labors are identical, women who have given birth before often are less anxious about the process, unless their previous experience has been negative.

Assessment

Assessment begins at the first contact with the woman, whether by telephone or in person. Many women call the hospital or birthing center first for validation that it is all right for them to come in for evaluation or admission or if it is all right for them to remain home. Many hospitals, however, discourage the nurse from giving advice regarding what to do because of legal liability. Nurses are often instructed to tell women who call with questions to call their primary health care provider or to come to the hospital if they feel the need to be checked. The nature of the telephone conversation including any advice or instructions given should be documented in the client’s record (Gilbert, 2011).

A pregnant woman may first call her primary care provider or come to the hospital while in false labor or early in the latent phase of the first stage of labor. She may feel discouraged, angry, or confused on learning that the contractions that feel so strong and regular to her are not true contractions because they are not causing cervical dilation, or that they are still not strong or frequent enough for admission. During the third trimester of pregnancy, women should be instructed regarding the stages of labor and the signs indicating its onset. They should be informed of the possibility that they will not be admitted if they are 3 cm or less dilated (see the Teaching for Self-Management box).

If the woman lives near the hospital and has adequate support and transportation, she may be encouraged to stay home or return home to allow labor to progress (i.e., until the uterine contractions are more frequent and intense). The ideal setting for the low risk woman at this time usually is the familiar environment of her home. The woman who lives at a considerable

distance from the hospital, who lacks adequate support and transportation, or who has a history of rapid labors in the past, however, may be admitted in latent labor. The same measures used by the woman at home should be offered to the hospitalized woman in early labor.

A warm shower is often relaxing during early labor. However, warm baths before labor is well established could inhibit uterine contractions and prolong the labor process (Waterbirth International, 2009). Soothing back, foot, and hand massage or a warm drink of preferred liquids such as tea or milk can help the woman to rest and even to sleep, especially if false or early labor is occurring at night. Diversional activities such as walking outdoors or in the house, reading, watching television, knitting, or talking with friends can reduce the perception of early discomfort, help the time pass, and reduce anxiety.

When the woman arrives at the perinatal unit, assessment is the top priority (Fig. 19-1). The nurse first performs a screening assessment by using the techniques of interview and physical assessment and reviews the laboratory and diagnostic test findings to determine the health status of the woman and her fetus and the progress of her labor. The nurse also notifies the primary health care provider and if the woman is admitted, a detailed systems assessment is done.

FIG. 19-1 Woman being assessed for admission to the labor and birth unit. (Courtesy Dee Lowdermilk, Chapel Hill, NC.)

When the woman is admitted, she is usually moved from an observation area to the labor room; the labor, delivery, and recovery (LDR) room; or the labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum (LDRP) room. If the woman wishes, include her partner in the assessment and admission process. The nurse can direct

significant others not participating in this process to the appropriate waiting area. The woman undresses and puts on her own gown or a hospital gown. The nurse places an identification band on the woman’s wrist. Her personal belongings are put away safely or given to family members, according to agency policy. Women who participate in expectant parents classes often bring a birth bag or Lamaze bag with them. The nurse then shows the woman and her partner the layout and operation of the unit and room, how to use the call light and telephone system, and how to adjust lighting in the room and the different bed positions.

The nurse reassures the woman that she is in competent, caring hands and that she and persons to whom she gives permission can ask questions related to her care and status and that of her fetus at any time during labor. The nurse can minimize the woman’s anxiety by explaining terms commonly used during labor. The woman’s interest, response, and prior experience guide the depth and breadth of these explanations.

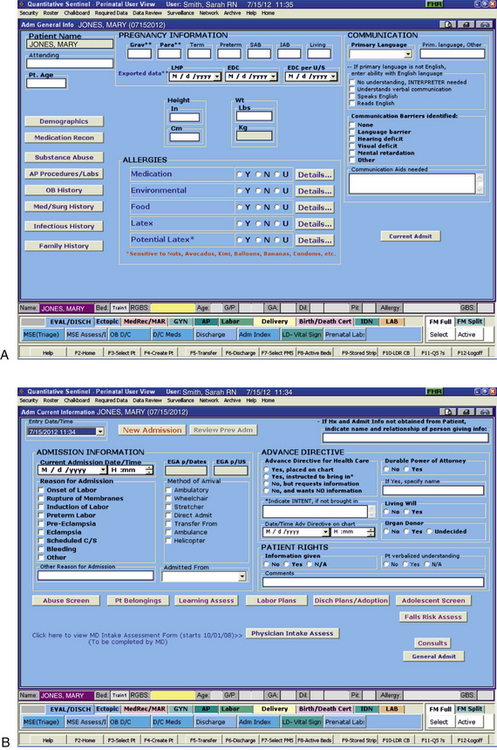

Most hospitals have specific forms, whether paper or electronic, which are used to obtain important assessment information when a woman in labor is being evaluated or admitted (Fig. 19-2). More and more hospitals now use an electronic medical record—almost all charting is done on computer. Sources of data include the prenatal record, the initial interview, physical examination to determine baseline physiologic parameters (e.g., vital signs), laboratory and diagnostic test results, expressed psychosocial and cultural factors, and the clinical evaluation of labor status.

FIG. 19-2 Admission screens in an electronic medical record. A, General admission screen. B, Current admission screen. (Courtesy Kitty Cashion, Memphis, TN).

Prenatal Data

The nurse reviews the prenatal record to identify the woman’s individual needs and risks. Copies of prenatal records are generally filed in the perinatal unit at some time during the woman’s pregnancy (usually in the third trimester) or accessed by computer so that they are readily available on admission. If the woman has had no prenatal care or her prenatal records are unavailable, the nurse must obtain certain baseline information. If the woman is having discomfort, the nurse should ask questions between contractions when the woman can concentrate more fully on her answers. At times the partner or support person(s) may need to be secondary sources of essential information. According to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the woman must give permission for other persons to be involved in the exchange of information regarding her care. This permission should be obtained during pregnancy and a signed form included in her health records.

Knowing the woman’s age is important so that the nurse can individualize the nursing care plan to the needs of her age-group. For example, a 14-year-old girl and a 40-year-old woman have different but specific needs, and their ages place them at risk for different problems. Accurate height and weight measurements are important. A pregnancy weight gain greater than recommended may place the woman at a higher risk for cephalopelvic disproportion and cesarean birth. This is especially true for women who are petite and have gained 16 kg or more. A prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 is also a cause for concern. Other factors to consider are the woman’s general health status, current medical conditions or allergies, respiratory status, and previous surgical procedures.

The nurse should carefully review the woman’s prenatal records, taking note of her obstetric and pregnancy history including gravidity, parity, and problems such as history of vaginal bleeding, gestational hypertension, anemia, pregestational or gestational diabetes, infections (e.g., bacterial, viral, sexually transmitted), and immunodeficiency status. In addition, the expected date of birth (EDB) should be confirmed. Other important data found in the prenatal record include patterns of maternal weight gain; physiologic measurements such as maternal vital signs (blood pressure, temperature, pulse, respirations); fundal height; baseline fetal heart rate (FHR); and laboratory and diagnostic test results. See Table-15-1 for a list of common prenatal laboratory tests. Common diagnostic and fetal assessment tests performed prenatally include amniocentesis, nonstress test (NST), biophysical profile (BPP), and ultrasound examination. See Chapter 26 for more information.

If this labor and birth experience is not the woman’s first, the nurse needs to note the characteristics of her previous experiences. This information includes the duration of previous labors, the type of anesthesia used, the kind of birth (e.g., spontaneous vaginal, forceps-assisted, vacuum-assisted, or cesarean birth), and the condition of the newborn. Explore the woman’s perception of her previous labor and birth experiences because this perception may influence her attitude toward her current experience.

Interview

The woman’s primary reason for coming to the hospital is determined in the interview. Her primary reason may be, for example, that her bag of waters (BOW, amniotic membranes) ruptured, with or without contractions. The woman may have come in for an obstetric check, which is a period of observation reserved for women who are unsure about the onset of their labor. This check allows time on the unit for the diagnosis of labor without official admission and minimizes or avoids cost to the woman when used by the hospital and approved by her health insurance plan.

Even the experienced woman may have difficulty determining the onset of labor. The woman is asked to recall the events of the previous days and to describe the following:

• Time and onset of contractions and progress in terms of frequency, duration, and intensity

• Location and character of discomfort from contractions (e.g., back pain, abdominal or suprapubic discomfort)

• Persistence of contractions despite changes in maternal position and activity (e.g., walking or lying down)

• Presence and character of vaginal discharge or “show”

• The status of amniotic membranes, such as a gush or seepage of fluid (spontaneous rupture of membranes [SROM]). If there has been a discharge that may be amniotic fluid, she is asked the date and time the fluid was first noted and the fluid’s characteristics (e.g., amount, color, unusual odor). In many instances, a sterile speculum examination and a Nitrazine (pH) and fern test can confirm that the membranes are ruptured (see the Procedure box: Tests for Rupture of Membranes).

These descriptions help the nurse assess the degree of progress in the process of labor. Bloody show is distinguished from bleeding by the fact that it is pink and feels sticky because of its mucoid nature. There is very little bloody show in the beginning, but the amount increases with effacement and dilation of the cervix. A woman may report a small amount of brownish to bloody discharge that may be attributed to cervical trauma resulting from vaginal examination or coitus (intercourse) within the last 48 hours.

Assessing the woman’s respiratory status is important in case general anesthesia is needed in an emergency. The nurse determines this status by asking the woman if she has a “cold” or related symptoms (e.g., “stuffy nose,” sore throat, or cough). The status of allergies, including allergies to latex and tape, and medications routinely used in obstetrics, such as opioids (e.g., hydromorphone [Dilaudid], butorphanol [Stadol], fentanyl [Sublimaze], nalbuphine [Nubain]), anesthetic agents (e.g., bupivacaine, lidocaine, ropivacaine), and antiseptics (Betadine) is reviewed. Some allergic responses cause swelling of the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract, which could interfere with breathing and the administration of inhalation

anesthesia. Because vomiting and subsequent aspiration into the respiratory tract can complicate an otherwise normal labor, the nurse records the time and type of the woman’s most recent solid and liquid intake.

The nurse obtains any information not found in the prenatal record during the admission assessment. Pertinent data include the birth plan (Box 19-1), the choice of infant feeding method, the type of pain management preferred, and the name of the pediatric health care provider. Obtain a client profile that identifies the woman’s preparation for childbirth, the support person or family members desired during childbirth and their availability, and ethnic or cultural expectations and needs. Determine the woman’s use of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco before or during pregnancy.

The nurse reviews the birth plan. If no written plan has been prepared, then the nurse helps the woman formulate a birth plan by describing options available and determining the woman’s wishes and preferences. As caregiver and advocate the nurse integrates the woman’s desires into the nursing care plan as much as possible. The nurse also prepares the woman for the possibility of change in her plan as labor progresses and assures her that the staff will provide information so that she can make informed decisions. The woman must also realize, however, that the longer her list of “wishes” is, the greater the likelihood that her expectations will not be met.

The nurse should discuss with the woman and her partner their plans for preserving childbirth memories through the use of photography and videotaping. Information should be provided about the agency’s policies regarding these practices and under what circumstances they are allowed. Protection of privacy and safety and infection control are major concerns for the expecting parents and the agency. To avoid future embarrassment and distress, the nurse should clarify with the woman exactly what parts of her childbirth she wishes to have photographed and the degree of detail. The woman’s record should reflect that the childbirth was recorded. Some hospitals and health care providers do not allow videotaping of the birth because of concerns related to legal liability.

Psychosocial Factors

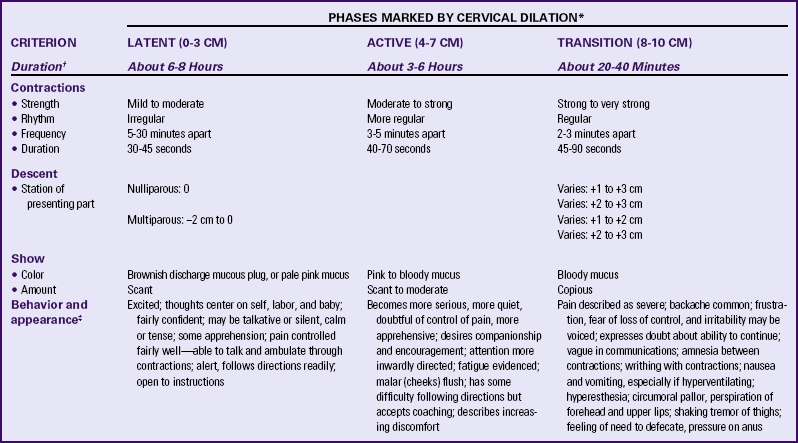

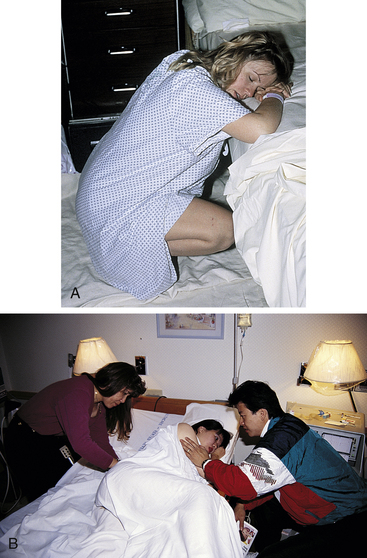

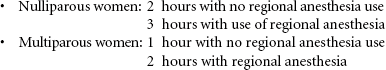

The woman’s general appearance and behavior (and that of her partner) provide valuable clues to the type of supportive care she will need. However, keep in mind that general appearance and behavior may vary, depending on the stage and phase of labor (Table 19-1 and Box 19-2).

TABLE 19-1

EXPECTED MATERNAL PROGRESS IN FIRST STAGE OF LABOR

∗In the nullipara, effacement is often complete before dilation begins; in the multipara, it occurs simultaneously with dilation.

†Duration of each phase is influenced by such factors as parity, maternal emotions, position, level of activity, and fetal size, presentation, and position. For example, the labor of a nullipara tends to last longer, on average, than the labor of a multipara. Women who ambulate and assume upright positions or change positions frequently during labor tend to experience a shorter first stage. Descent is often prolonged in breech presentations and occiput posterior positions.

‡Women who have epidural analgesia for pain relief may not demonstrate some of these behaviors.

Women with a History of Sexual Abuse

Labor can trigger memories of sexual abuse, especially during intrusive procedures such as vaginal examinations. Monitors, intravenous (IV) lines, and epidurals can make the woman feel a loss of control or feel as if she is being confined to bed and “restrained.” Being observed by students and having intense sensations in the uterus and genital area, especially at the time when she must push the baby out, can also trigger memories.

The nurse can help the abuse survivor to associate the sensations she is experiencing with the process of childbirth and not with her past abuse. Help maintain her sense of control by explaining all procedures and why they are needed, validating her needs, and paying close attention to her requests. Wait for the woman to give permission before touching her, and accept her often extreme reactions to labor (Simpson, 2008). Avoid words and phrases that can cause the woman to recall the words of her abuser (e.g., “open your legs,” “relax and it won’t hurt so much”). Limit the number of procedures that invade her body (e.g., vaginal examinations, urinary catheter, internal monitor, forceps or vacuum extractor) as much as possible. Encourage her to choose a person (e.g., doula, friend, family member) to be with her during labor to provide continuous support and comfort and to act as her advocate. Nurses are advised to care for all laboring women in this manner because it is not unusual for a woman to choose not to reveal a history of sexual abuse. These care measures can help a woman perceive her childbirth experience in positive terms.

Stress in Labor

The way in which women and their support person or family members approach labor is related to the manner in which they have been socialized to the childbearing process. Their reactions reflect their life experiences regarding childbirth–physical, social, cultural, and religious. Society communicates its expectations regarding acceptable and unacceptable maternal behaviors during labor and birth. These expectations may be used by some women as the basis for evaluating their own actions during childbirth. An idealized perception of labor and birth may be a source of guilt and cause a sense of failure if the woman finds the process less than joyous, especially when the pregnancy is unplanned or is the product of a dysfunctional or terminated relationship. Often women have heard horror stories or have seen friends or relatives going through labors that appear anything but easy. Multiparous women will often base their expectations of the present labor on their previous childbirth experiences.

Discuss the feelings a woman has about her pregnancy and fears regarding childbirth. This discussion is especially important if the woman is a primigravida who has not attended childbirth classes or is a multiparous woman who has had a previous negative childbirth experience. Women in labor usually have a variety of concerns that they will voice if asked but rarely volunteer. Major fears and concerns relate to the process and effects of childbirth, maternal and fetal well-being, and the attitude and actions of the health care staff. Unresolved fears increase a woman’s stress and can slow the process of labor as a result of the inhibiting effects of catecholamines associated with the stress response on uterine contractions (Zwelling, Johnson, & Allen, 2006).

The father, coach, or significant other also experiences stress during labor. The nurse can assist and support these individuals by identifying their needs and expectations and by helping make sure these are met. The nurse can determine what role the support person intends to fulfill and whether he or she is prepared for that role by making observations and asking herself or himself such questions as, “Has the couple attended childbirth classes?” “What role does this person expect to play?” “Does he or she do all the talking?” “Is he or she nervous, anxious, aggressive, or hostile?” “Does he or she look hungry, tired, worried, or confused?” “Does he or she watch television, sleep, or stay out of the room instead of paying attention to the woman?” “Where does he or she sit?” “Does he or she touch the woman; what is the character of the touch?” Be sensitive to the needs of support persons and provide teaching and support as appropriate. In many instances the support these persons provide to the laboring woman is in direct proportion to the support they receive from the nurses and other health care providers.

Cultural Factors

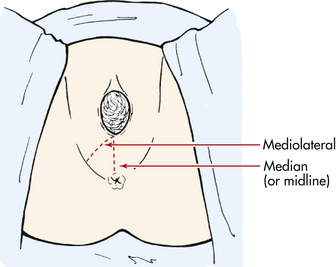

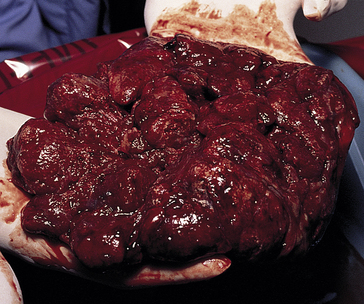

Currently more than 30% of the population in the United States comes from cultural groups other than non-Hispanic whites compared with only 9% of registered nurses (Callister, 2008). As the population in the United States and Canada becomes more diverse, it is increasingly important to note the woman’s ethnic or cultural and religious values, beliefs, and practices in order to anticipate nursing interventions to add or eliminate from an individualized, mutually acceptable plan of care that provides a feeling of safety and control (Fig. 19-3). Nurses should be committed to providing culturally sensitive care and to developing an appreciation and respect for cultural diversity (Callister, 2005; 2008). Encourage the woman to request specific caregiving behaviors and practices that are important to her. If a special request contradicts usual practices in that setting, the woman or the nurse can ask the woman’s primary health care provider to write an order to accommodate the special request. For example, in many cultures, it is unacceptable to have a male caregiver examine a pregnant woman. In some cultures, it is traditional to take the placenta home; in others, the woman has only certain nourishments during labor. Some women believe that cutting her body, as with an episiotomy, allows her spirit to leave her body and that rupturing the membranes prolongs, not shortens, labor. It is important to explain the rationale for required care measures carefully (see the Cultural Considerations box).

FIG. 19-3 Birthing room specific to a Native-American population. Note the arrow pointing east, the rug on the wall, and the rope or sash belt hanging from the ceiling. (Courtesy Patricia Hess, San Francisco, CA; Chinle Comprehensive Health Care Center, Chinle, AZ.)

Within cultures, women may have an idea of the “right” way to behave in labor and may react to the pain experienced in that way. These behaviors can range from total silence to moaning or screaming, but they do not necessarily indicate the degree of pain. A woman who moans with contractions may not be in as much physical pain as a woman who is silent but winces during contractions. Some women believe that screaming or crying out in pain is shameful if a man is present. If the woman’s support

person is her mother, she may perceive the need to “behave” more strongly than if her support person is the father of the baby. She will perceive herself as failing or succeeding based on her ability to follow these “standards” of behavior. Conversely, a woman’s behavior in response to pain may influence the support received from significant others. In some cultures, women who lose control and cry out in pain may be scolded, whereas in other cultures, support persons will become more helpful (D’Avanzo, 2008).

Culture and Father Participation

A companion is an important source of support, encouragement, and comfort for women during childbirth. The woman’s cultural and religious background influences her choice of birth companion as do trends in the society in which she lives. For example, in Western societies the father is viewed as the ideal birth companion. For European-American couples, attending childbirth classes together has become a traditional, expected activity. Laotian (Hmong) husbands also traditionally participate actively in the labor process. In some other cultures the father may be available, but his presence in the labor room with the mother may not be considered appropriate, or he may be present but resist active involvement in her care. Such behavior could be perceived by the nursing staff to indicate a lack of concern, caring, or interest. Women from many cultures prefer female caregivers and want to have at least one female companion present during labor and birth. They also are usually very concerned about modesty. If couples from these cultures immigrate to the United States or Canada, their roles may change. The nurse needs to talk to the woman and her support persons to determine the roles they will assume.

The Non–English-Speaking Woman in Labor

A woman’s level of anxiety in labor increases when she does not understand what is happening to her or what is being said. Non–English-speaking women often feel a complete loss of control over their situation if no health care provider is present who speaks their language. They can panic and withdraw or become physically abusive when someone tries to do something they perceive might harm them or their babies. A support person is sometimes able to serve as an interpreter. However, caution is warranted because the interpreter may not be able to convey exactly what the nurse or others are saying or what the woman is saying, which can increase the woman’s stress level even more.

Ideally, a bilingual nurse will care for the woman. Alternatively a hospital employee or volunteer interpreter may be contacted for assistance (see Box 2-2). Ideally, the interpreter is from the woman’s culture. For some women a female is more acceptable than a male interpreter. If no one in the hospital is able to interpret, call a service so that interpretation can take place over the telephone. Even when the nurse has limited ability to communicate verbally with the woman, in most instances the woman appreciates the nurse’s efforts to do so. Speaking slowly and avoiding complex words and medical terms can help a woman and her partner understand. Often the woman understands English much better than she speaks it.

Physical Examination

The initial physical examination includes a general systems assessment and an assessment of fetal status. During the examination uterine contractions are assessed and a vaginal examination is performed. The findings of the admission physical examination serve as a baseline for assessing the woman’s progress from that point. See Chapter 4 for information regarding physical examination of women with disabilities.

The information obtained from a complete and accurate assessment during the initial examination serves as the basis for determining whether the woman should be admitted and what her ongoing care should be. Expected maternal progress and minimal assessment guidelines during the first stage of labor are presented in Table 19-1 and the Nursing Process Box: First Stage of Labor.

Birth is a time when nurses and other health care providers are exposed to a great deal of maternal and newborn blood and body fluids. Therefore, Standard Precautions should guide all assessment and care measures (Box 19-3). Hand hygiene

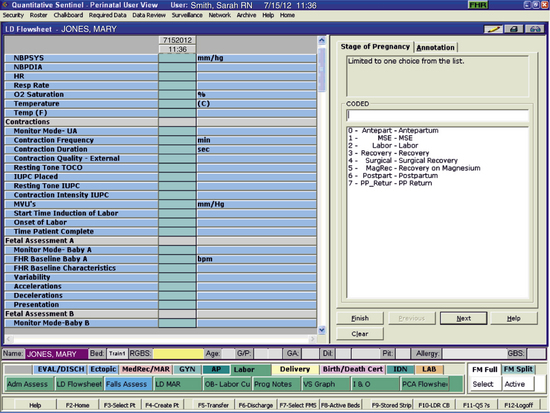

(e.g., washing hands with soap or application of an alcohol-based antiseptic rub) before and after assessing the woman and providing care is a critical step in the prevention of infection transmission. The nurse should explain assessment findings to the woman and her partner whenever possible. Throughout labor, accurate documentation, following agency policy, is done as soon as possible after a procedure has been performed (Fig. 19-4).

FIG. 19-4 Portion of the labor flowsheet screen in an electronic medical record. (Courtesy Kitty Cashion, Memphis, TN).

General Systems Assessment

On admission, the nurse should perform a brief systems assessment. This includes an assessment of the heart, lungs, and skin and an examination to determine the presence and extent of edema of the face, hands, sacrum, and legs. It also includes testing of deep tendon reflexes and for clonus if indicated. Also note the woman’s weight. Increasing numbers of women are overweight or obese. Excessive size can make nursing care during labor and birth more difficult and places the woman at risk for complications such as operative birth, infection, and blood clots. See Chapter 33 for further information.

Vital Signs

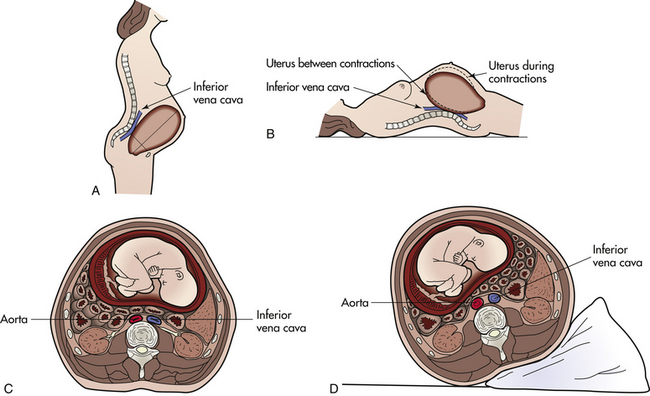

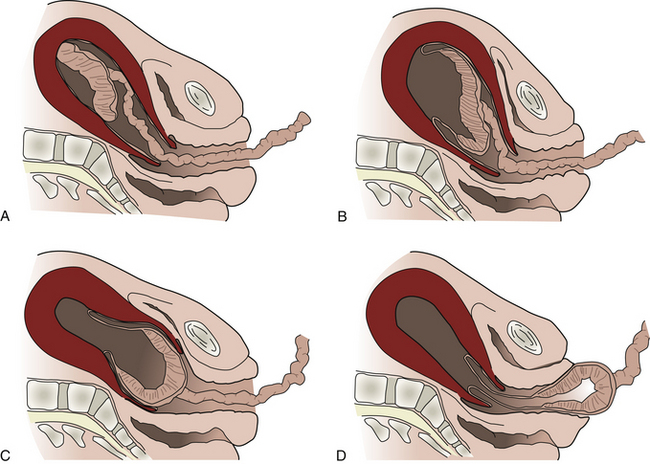

Assess vital signs (temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure using a correct size cuff) on admission. The initial values are used as the baseline for comparison for all future measurements. If the blood pressure is elevated, reassess it 30 minutes later, between contractions, to obtain a reading after the woman has relaxed. Encourage the woman to lie on her side to prevent supine hypotension and fetal distress (Fig. 19-5). Monitor her temperature so that you can identify signs of infection or a fluid deficit (e.g., dehydration associated with inadequate intake of fluids).

FIG. 19-5 Supine hypotension. Note relation of pregnant uterus to ascending vena cava in standing position (A), and in the supine position (B). C, Compression of aorta and inferior vena cava with woman in supine position. D, Compression of these vessels is relieved by placement of a wedge pillow under the woman’s right side.

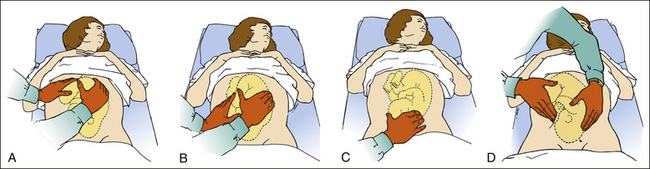

Leopold Maneuvers (Abdominal Palpation)

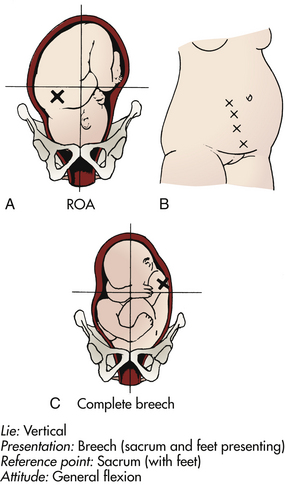

Leopold maneuvers are performed with the woman briefly lying on her back (see the Procedure box: Leopold Maneuvers). These maneuvers help identify the (1) number of fetuses; (2) presenting part, fetal lie, and fetal attitude; (3) degree of the presenting part’s descent into the pelvis; and (4) expected location of the point of maximal intensity (PMI) of the FHR on the woman’s abdomen.

Assessment of Fetal Heart Rate and Pattern

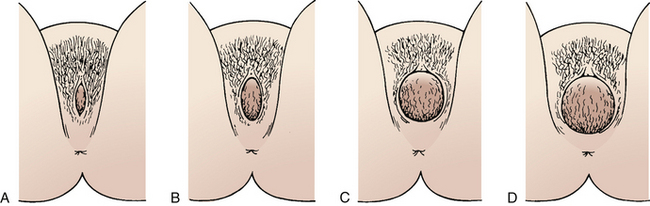

The PMI of the FHR is the location on the maternal abdomen at which the FHR is heard the loudest. It is usually directly over the fetal back (Fig. 19-6). In a vertex presentation, you can usually hear the FHR below the mother’s umbilicus in either the right or the left lower quadrant of the abdomen. In a breech presentation you usually hear the FHR above the mother’s umbilicus. The Nursing Process Box: First Stage of Labor summarizes assessments recommended for determining fetal status. In addition, you must assess the FHR after ROM because this is the most common time for the umbilical cord to prolapse, after any change in the contraction pattern or maternal status, and before and after the woman receives medication or a procedure is performed (Tucker et al., 2009).

FIG. 19-6 Location of the fetal heart tones (FHTs). A, FHTs with fetus in right occipitoanterior (ROA) position. B, Changes in location of point of maximal intensity of FHTs as fetus undergoes internal rotation from ROA to OA and descent for birth. C, FHTs with fetus in left sacrum posterior position. (A and C, Courtesy Ross Laboratories, Columbus, OH.)

Assessment of Uterine Contractions

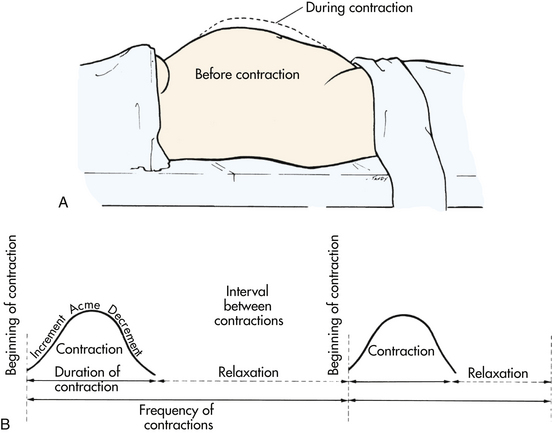

A general characteristic of effective labor is regular uterine activity (i.e., contractions becoming more frequent with increased duration), but uterine activity is not directly related to labor progress. Uterine contractions are the primary powers that act involuntarily to expel the fetus and the placenta from the uterus. Several methods are used to evaluate uterine contractions, including the woman’s subjective description, palpation and timing of contractions by a health care provider, and electronic monitoring.

Each contraction exhibits a wavelike pattern. It begins with a slow increment (the “building up” of a contraction from its onset), gradually reaches a peak, and then diminishes rapidly (decrement, the “letting down” of the contraction). An interval of rest ends when the next contraction begins. The outward appearance of the woman’s abdomen during and between contractions and the pattern of a typical uterine contraction are shown in Figure 19-7.

FIG. 19-7 Assessment of uterine contractions. A, Abdominal contour before and during uterine contraction. B, Wavelike pattern of contractile activity.

A uterine contraction is described in terms of the following characteristics:

• Frequency: How often uterine contractions occur; the time that elapses from the beginning of one contraction to the beginning of the next contraction

• Intensity: The strength of a contraction at its peak

• Duration: The time that elapses between the onset and the end of a contraction

• Resting tone: The tension in the uterine muscle between contractions; relaxation of the uterus

Uterine contractions are assessed by palpation or by using an external or internal electronic monitor (see Chapter 18 for further discussion). Frequency and duration can be measured by all three methods of uterine activity monitoring. The accuracy of determining intensity and resting tone varies by the method used. The woman’s description and palpation are more subjective and less precise ways of determining the intensity of uterine contractions and resting tone than is the electronic fetal monitor. The following terms describe what is felt on palpation:

• Mild: Slightly tense fundus that is easy to indent with fingertips (feels like touching finger to tip of nose)

• Moderate: Firm fundus that is difficult to indent with fingertips (feels like touching finger to chin)

• Strong: Rigid boardlike fundus that is almost impossible to indent with fingertips (feels like touching finger to forehead)

Women in labor tend to describe the pain of contractions in terms of the sensations they are experiencing in the lower abdomen or back, which are sometimes unrelated to the firmness of the uterine fundus. Therefore, their assessment of the strength of their contractions can be less accurate than that of the health care provider, although the amount of discomfort reported is valid.

External electronic monitoring provides some information about the strength of uterine contractions when the appearance of contractions on admission is compared to those that occur later in labor. Internal electronic monitoring with an intrauterine pressure catheter, however, is the most accurate way of assessing the intensity of uterine contractions and resting tone.

On admission, at least a 20- to 30-minute baseline monitoring period of uterine contractions and the fetal heart rate and pattern commonly is done using electronic monitors. The minimal times for assessing uterine activity during the various phases of labor are given in the Nursing Process boxes for the First Stage of Labor; the Second Stage of Labor and the findings expected as labor progresses are summarized in Tables 19-1 and 19-3.

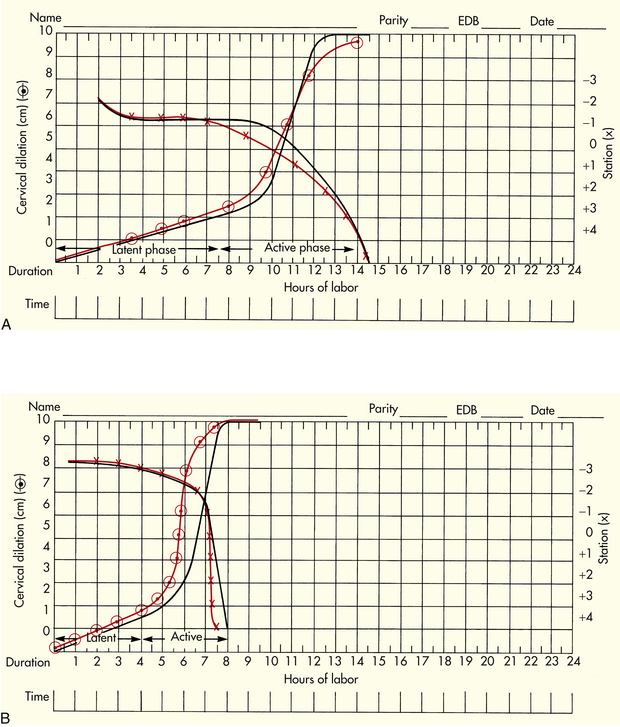

You must consider uterine activity in the context of its effect on cervical effacement and dilation and on the degree of descent of the presenting part (see Chapter 16). You must also consider the effect on the fetus. You can verify the progress of labor effectively through the use of graphic charts (partograms) on which you plot cervical dilation and station (descent). This type of graphic charting assists in early identification of deviations from expected labor patterns. Figure 19-8 provides examples of partograms. Hospitals and birthing centers may develop their own assessment graphs that may include data not only on dilation and descent but also maternal vital signs, FHR, and uterine activity.

FIG. 19-8 Partograms for assessment of patterns of cervical dilation and descent. Individual woman’s labor patterns (colored) are superimposed on prepared labor graph (black) for comparison. A, Labor of a nulliparous woman. B, Labor of a multiparous woman. The rate of cervical dilation is plotted with the circled plot points. A line drawn through these symbols depicts the slope of the curve. Station is plotted with Xs. A line drawn through the Xs reveals the pattern of descent.

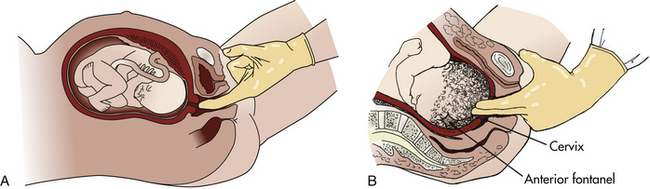

Vaginal Examination

The vaginal examination reveals whether the woman is in true labor and enables the examiner to determine whether the membranes have ruptured (Fig. 19-9). Because this examination is often stressful and uncomfortable for the woman, perform it only when indicated by the status of the woman and her fetus. For example, you should perform a vaginal examination on admission, prior to administering medications (e.g., analgesics, increasing oxytocin infusion), when significant change has occurred in uterine activity, on maternal perception of perineal pressure or the urge to bear down, when membranes rupture, or when you note variable decelerations of the FHR. A full explanation of the examination and support of the woman are important in reducing the stress and discomfort associated with the examination (Simpson, 2008) (see the Procedure box: Vaginal Examination of the Laboring Woman.)

Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

A clean-catch urine specimen may be obtained to gather further data about the pregnant woman’s health. Analysis of the specimen is a convenient and simple procedure that can provide information about her hydration status (e.g., specific gravity, color, amount), nutritional status (e.g., ketones), infection status (e.g., leukocytes), or the status of possible complications such as preeclampsia, shown by finding protein in the urine. In most hospitals this test must be done in the laboratory rather than at the bedside, even if a urine “dipstick” is used.

Blood Tests

The blood tests performed vary with the hospital protocol and the woman’s health status. Currently, all blood tests must be performed in the hospital laboratory rather than on the perinatal unit. Often blood samples are obtained from the hub of the catheter when an IV is started. A hematocrit will likely be ordered. More comprehensive blood assessments such as white blood cell count, red blood cell count, hemoglobin level, hematocrit, and platelet values are included in a complete blood count (CBC). A CBC may be ordered for women with a history of infection, anemia, gestational hypertension, or other disorders. Any woman whose human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status is undocumented at the time of labor should be screened with a rapid HIV test unless she declines (opts out) of testing (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Branson, Handsfield, Lampe, Janssen, & Taylor, et al., 2006).

Most hospitals require that a “type and screen,” to determine the woman’s blood type and Rh status, be performed on admission. Even if these tests have already been performed during pregnancy, the hospital’s laboratory or blood bank must verify the results in-house. If the woman had no prenatal care or if her prenatal records are not available, a prenatal screen will probably be drawn on admission. The prenatal screen includes laboratory tests that would normally have been drawn at the initial prenatal visit (see Table 15-2).

Other Tests

If the woman’s group B streptococci status is not known, a rapid test may be done on admission. The rapid test results are usually available within an hour or so and will determine if the woman must be given antibiotics during labor.

Assessment of Amniotic Membranes and Fluid

Labor is initiated at term by SROM in approximately 25% of pregnant women. A lag period, rarely exceeding 24 hours, may precede the onset of labor. Membranes (the BOW) also can rupture spontaneously any time during labor, but most commonly in the transition phase of the first stage of labor. The Procedure box: Tests for Rupture of Membranes explains how to determine if membranes are ruptured. If the membranes do not rupture spontaneously, the BOW will likely be ruptured artificially at some time during labor. Artificial rupture of membranes (AROM), called an amniotomy, is performed by the physician or certified nurse-midwife using a plastic AmniHook or a surgical clamp.

Whether the membranes rupture spontaneously or artificially, the time of rupture should be recorded. Other necessary documentation includes information regarding the color (clear or meconium-stained), estimated amount, and odor of the fluid. See Chapter 33 for additional information.

Infection: When membranes rupture, microorganisms from the vagina can then ascend into the amniotic sac, causing chorioamnionitis and placentitis to develop. For this reason assess maternal temperature and vaginal discharge frequently (at least every 2 hours) so that you can quickly identify an infection developing after ROM. Even when membranes are intact, however, microorganisms may ascend and cause infection.

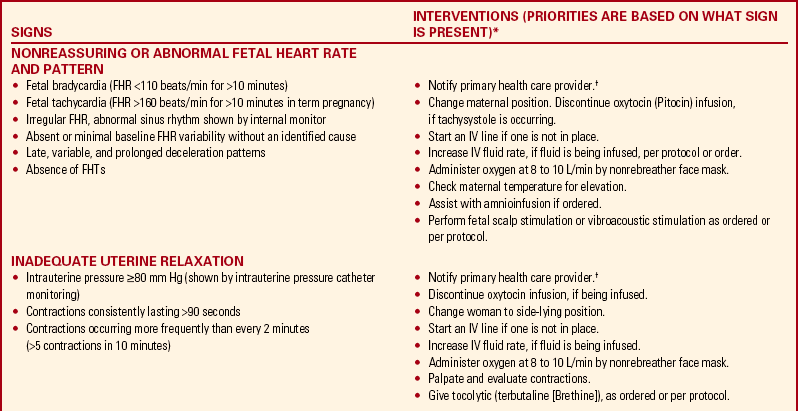

Assessment findings serve as a baseline for evaluating the woman’s subsequent progress during labor. Although some problems can be anticipated, others may appear unexpectedly during the clinical course of labor (see the Signs of Potential Complications box).

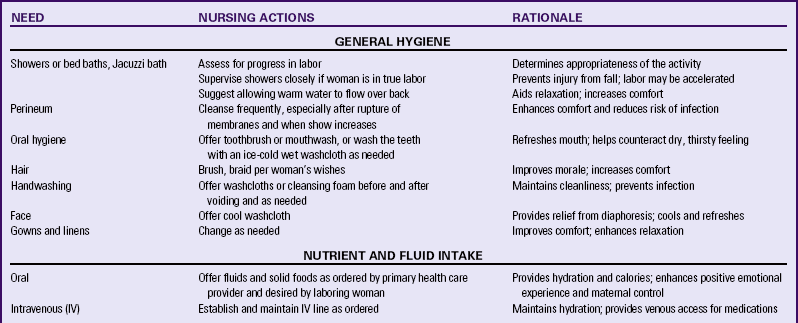

Nursing Care

The nursing process provides the framework for the nursing care management of women in labor. The physical nursing care given to a woman in labor is an essential component of her care. The current emphasis on evidence-based practice supports the management of care by using this approach to enhance the safety, effectiveness, and acceptability of the physical care measures chosen to support the woman during labor and birth (Box 19-4). The various physical needs, the necessary nursing actions, and the rationale for care are presented in Table 19-2, the Nursing Care Plan and the Nursing Process box: First Stage of Labor.

General Hygiene

Offer women in labor the use of showers or warm-water baths, if they are available, to enhance the feeling of well-being and to minimize the discomfort of contractions. ![]() Water immersion during active labor is associated with decreases in the use of analgesia and in reported maternal pain (Berghella, Baxter, & Chauhan, 2008). Also encourage women to wash their hands or use cleansing foam after voiding and to perform self-hygiene measures.

Water immersion during active labor is associated with decreases in the use of analgesia and in reported maternal pain (Berghella, Baxter, & Chauhan, 2008). Also encourage women to wash their hands or use cleansing foam after voiding and to perform self-hygiene measures.

Change the linen if it becomes wet or stained with blood, and use linen savers (Chux), changing them as needed.

Nutrient and Fluid Intake

Prior to the 1940s women were allowed to eat and drink during labor to maintain the energy required to sustain labor and the stamina required to give birth. This practice changed, allowing the laboring woman only clear liquids or ice chips or nothing by mouth during the active phase of labor when concern arose regarding the risk of anesthesia complications and their secondary effects if general anesthesia were required in an emergency. These secondary effects include the aspiration of gastric contents and resultant compromise in oxygen perfusion, which could endanger the lives of the mother and fetus (Simpson, 2008). There have been no randomized trials evaluating the ingestion of solid foods in labor, so current management is based mostly on expert opinions. Ice chips and sips of clear liquids are still the only oral intake recommended during labor in the United States by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetrical Anesthesia (Berghella et al., 2008). This practice is being challenged by some health care providers, however, because regional anesthesia is used more often than general anesthesia, even for emergency cesarean births. Women are awake during regional anesthesia and are able to participate in their own care and protect their airway.

An adequate intake of fluids and calories is required to meet the energy demands and fluid losses associated with childbirth. The progress of labor slows, with a more rapid development of hypoglycemia and ketosis if these demands are not met and fat is metabolized. Reduced energy for bearing-down efforts (pushing) increases the risk for a forceps- or vacuum-assisted birth. This is most likely to occur in women who begin to labor early in the morning after a night without caloric intake. When women are permitted to consume fluids and food freely, they typically regulate their own oral intake, eating light foods (e.g., eggs, yogurt, ice cream, dry toast and jelly, fruit) and drinking fluids during early labor and tapering off to the intake of clear fluids and sips of water or ice chips as labor intensifies and the second stage approaches (Parsons, Bidwell, & Nagy, 2006).

Common practice is to allow clear liquids (e.g., water, tea, fruit juices without pulp, clear sodas, coffee, sports drinks, fruit ice, Popsicles, gelatin, broth) during early labor, tapering off to ice chips and sips of water as labor progresses and becomes more active. Herbal teas can provide not only hydration but also other beneficial effects. ![]() Chamomile tea can enhance relaxation, lemon balm or peppermint tea can reduce nausea, and teas of ginger or ginseng root are energizing (Walls, 2009). A woman’s culture may influence what she will eat and drink during labor. In addition, women who use nonpharmacologic pain relief measures and labor at home or in birthing centers are more likely to eat and drink during labor. The amount of solid and liquid carbohydrates to offer a woman in labor is still unclear. Though it is known that energy needs increase as labor becomes prolonged, there is limited evidence regarding the effect of oral carbohydrate intake in enhancing the progress of labor and reducing the risk for dystocia (Tranmer, Hodnett, Hannah, & Stevens, 2005).

Chamomile tea can enhance relaxation, lemon balm or peppermint tea can reduce nausea, and teas of ginger or ginseng root are energizing (Walls, 2009). A woman’s culture may influence what she will eat and drink during labor. In addition, women who use nonpharmacologic pain relief measures and labor at home or in birthing centers are more likely to eat and drink during labor. The amount of solid and liquid carbohydrates to offer a woman in labor is still unclear. Though it is known that energy needs increase as labor becomes prolonged, there is limited evidence regarding the effect of oral carbohydrate intake in enhancing the progress of labor and reducing the risk for dystocia (Tranmer, Hodnett, Hannah, & Stevens, 2005).

Withholding food and fluids in labor is unlikely to be beneficial, and offering oral fluids is demonstrably useful and should be encouraged (Hofmeyr, 2005). Nurses should follow the orders of the woman’s primary health care provider when offering the woman food or fluids during labor. As advocates, however, nurses can facilitate change by informing others of the current research findings that support the safety and effectiveness of the oral intake of food and fluid during labor and by initiating such research themselves. ![]()

Intravenous Intake

Fluids are administered intravenously to the laboring woman to maintain hydration, especially when a labor is long and the woman is unable to ingest a sufficient amount of fluid orally or if she is receiving epidural or intrathecal anesthesia. In most cases an electrolyte solution without glucose (e.g., Ringer’s lactate or normal saline) is adequate and does not introduce excess glucose into the bloodstream. The latter is important because an excessive maternal glucose level results in fetal hyperglycemia and fetal hyperinsulinism. After birth the neonate’s high level of insulin will reduce his or her glucose stores, and hypoglycemia will result. Infusions containing glucose can also reduce sodium levels in the woman and the fetus, leading to transient neonatal tachypnea. If maternal ketosis occurs, the primary health care provider may order an IV solution containing a small amount of dextrose to provide the glucose needed to assist in fatty acid metabolism.

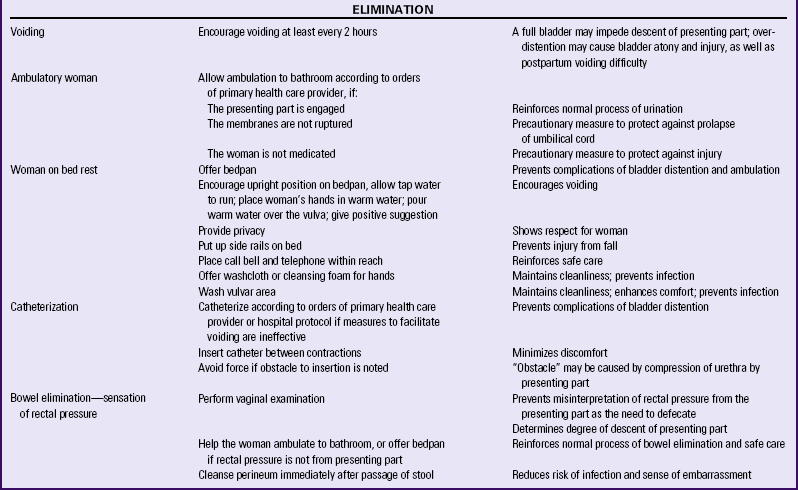

Elimination

Encourage voiding every 2 hours. A distended bladder may impede descent of the presenting part, slow or stop uterine contractions, and lead to decreased bladder tone or uterine atony after birth. Women who receive epidural analgesia or anesthesia are especially at risk for the retention of urine. Therefore, the need to void should be assessed more frequently with them.

Assist the woman to the bathroom to void or use a bedside commode, unless any of the following apply: the primary health care provider has ordered bed rest; the woman is receiving epidural analgesia or anesthesia; internal monitoring is being used; or ambulation will compromise the status of the laboring woman or her fetus. External monitoring can usually be interrupted long enough for the woman to go to the bathroom.

If using a bedpan is necessary, encourage spontaneous voiding by providing privacy and having the woman sit upright (as she would on a toilet). Other interventions to encourage urination, either in the bathroom or on the bedpan, are having the woman listen to the sound of water slowly running from a faucet, placing her hands in warm water, having her blow bubbles into a glass of water using a straw, or pouring warm water over the vulva and perineum using a peri bottle.

Catheterization

If the woman is unable to void and her bladder is distended, she may need to be catheterized. Many hospitals have protocols that rely on the nurse’s judgment concerning the need for catheterization. Before performing the catheterization, clean the vulva and perineum because vaginal show and amniotic fluid may be present. If an obstacle that prevents advancement of the catheter is present, this obstacle is most likely the presenting part. If you cannot advance the catheter, stop the procedure and notify the primary health care provider of the difficulty.

Bowel Elimination

Most women do not have bowel movements during labor because of decreased intestinal motility. Stool that has formed in the large intestine often moves downward toward the anorectal area as a result of pressure exerted by the fetal presenting part as it descends. This stool is often expelled during second-stage pushing and birth. However, the passage of stool with bearing-down efforts increases the risk of infection and may embarrass the woman, thereby reducing the effectiveness of her pushing efforts. To prevent these problems, the nurse should immediately cleanse the perineal area to remove any stool, while reassuring the woman that the passage of stool at this time is a normal and expected event, because the same muscles used to expel the baby also expel stool.

Routine use of enemas on admission for women at term has shown only modest benefits. There is a trend toward lower infection rates and the newborns have fewer lower respiratory tract infections and less need for antibiotics. However, because enemas cause discomfort for women and increase the costs of giving birth, the small benefits do not outweigh the disadvantages of this practice (Berghella et al., 2008). ![]() In addition, a recent Cochrane review of this topic found that the evidence does not support the routine use of enemas during labor (Reveiz, Gaitan, & Cuervo, 2007).

In addition, a recent Cochrane review of this topic found that the evidence does not support the routine use of enemas during labor (Reveiz, Gaitan, & Cuervo, 2007).

When the presenting part is deep in the pelvis, even in the absence of stool in the anorectal area, the woman may feel rectal pressure and think she needs to defecate. If the woman expresses the urge to defecate, the nurse should perform a vaginal examination to assess cervical dilation and station. When a multiparous woman experiences the urge to defecate, this often means birth will follow quickly.

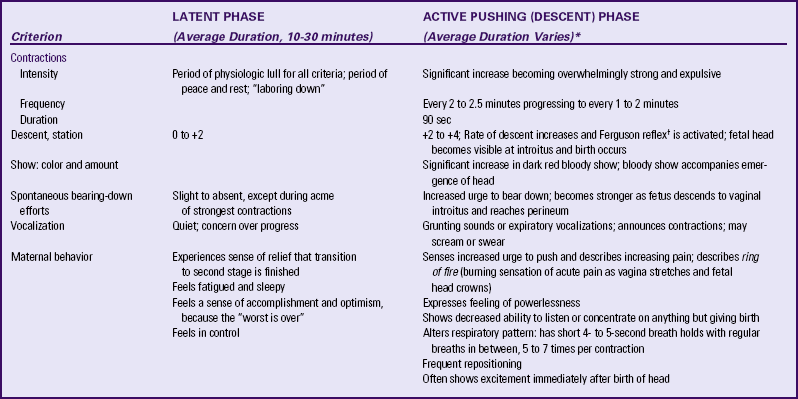

Ambulation and Positioning

Confinement to bed is the norm for labor management in the United States. The increased use of epidurals during childbirth accompanied by multiple medical interventions (e.g., monitors, intravenous infusions) and reduced motor control contribute to this practice, thereby interfering with a woman’s freedom of movement. Upright positions and mobility during labor, however, may be more pleasant for laboring women. These practices have also been associated with improved uterine contraction intensity and shorter labors, less need for pain medications, reduced rate of operative birth (e.g., cesarean birth, forceps- and vacuum-assisted birth), increased maternal autonomy and control, distraction from labor’s discomforts, and an opportunity for close interaction with the woman’s partner and care provider as they assist her to assume upright positions and remain mobile. No harmful effects have been observed from maternal activity and position changes (Albers, 2007; Simpson, 2008; Zwelling, 2010).

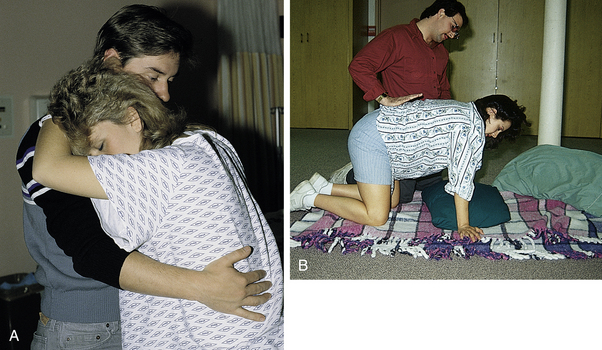

Encourage ambulation if membranes are intact, if the fetal presenting part is engaged after ROM, and if the woman has not received medication for pain (Fig. 19-10). The woman also may find it comfortable to stand and lean forward on her partner, doula, or nurse for support at times during labor (Fig. 19-11, A). Ambulation may be contraindicated, however, because of maternal or fetal status.

FIG. 19-10 Woman preparing to walk with partner. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

FIG. 19-11 A, Woman standing and leaning forward with support. B, Woman in hands-and-knees position. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

When the woman lies in bed, she will usually change her position spontaneously as labor progresses. If she does not change position every 30 to 60 minutes, assist her to do so. The side-lying (lateral) position is preferred because it promotes optimal uteroplacental and renal blood flow and increases fetal oxygen saturation (Fig. 19-12, B). If the woman wants to lie supine, the nurse should place a pillow under one hip as a wedge to prevent the uterus from compressing the aorta and vena cava (see Fig. 19-5). Sitting is not contraindicated unless it adversely affects fetal status, which you can determine by checking the FHR and pattern. If the fetus is in the occiput posterior position, it may be helpful to encourage the woman to squat during contractions because this position increases the pelvic diameter, allowing the head to rotate to a more anterior position (see Fig. 19-12, A). A hands-and-knees position during contractions or a lateral position on the same side as the fetal spine also are recommended to facilitate the rotation of the fetal occiput from a posterior to an anterior position, as gravity pulls the fetal back forward. These positions also provide access to the back for application of counterpressure by the partner, doula, or nurse (Hanson, 2009; Simpson. Cesario, Morin, Trapani, Mayberry, & Snelgrove-Clark, 2008; Zwelling, 2010) (see Fig. 19-11, B). Women with epidural anesthesia may not be able to squat or assume a hands-and-knees position depending on the degree of motor involvement resulting from the epidural.

FIG. 19-12 Maternal positions for labor. A, Squatting. B, Lateral position. Support person is applying sacral pressure while partner provides encouragement. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

Much research continues to focus on acquiring a better understanding of the physiologic and psychologic effects of maternal position in labor. Box 19-5 describes a variety of positions that are commonly used and recommended.

The woman can use a birth ball (gymnastic ball, physical therapy ball) to support her body as she assumes a variety of labor and birth positions (Fig. 19-13). She can sit on the ball while leaning over the bed, or lean over the ball to support her upper body and reduce stress on her arms and hands when she assumes a hands-and-knees position. The birth ball can encourage pelvic mobility and pelvic and perineal relaxation when the woman sits on the firm yet pliable ball and rocks in rhythmic movements. Warm compresses applied to the

FIG. 19-13 Woman laboring using birth ball. (Courtesy Polly Perez, Cutting Edge Press, Johnson, VT.)

perineum and lower back can maximize this relaxation and comfort effect. The birth ball should be large enough so that when the woman sits, her knees are bent at a 90-degree angle and her feet are flat on the floor and approximately 2 feet apart.

Supportive Care During Labor and Birth

Support during labor and birth involves emotional support, physical care and comfort measures, and advice and information. The value of the continuous supportive presence of a person (e.g., doula, childbirth educator, family member, friend, nurse, partner) during labor has long been known. Women who have continuous support beginning in early labor are less likely to use pain medication or epidurals, more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal birth, and less likely to report dissatisfaction with their birth experience. No harmful effects from continuous labor support have been identified. To the contrary, there is good evidence that labor support improves important health outcomes (Albers, 2007; Berghella et al., 2008; Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyer, & Sakala, 2007). ![]()

Labor rooms should be airy, clean, and homelike. The laboring woman should feel safe in this environment and free to be herself and to use the comfort and relaxation measures she prefers. To enhance relaxation, turn off bright overhead lights when not needed, and keep noise and intrusions to a minimum. Control the temperature to ensure the laboring woman’s comfort. The room should be large enough to accommodate a comfortable chair for the woman’s partner, the monitoring equipment, and hospital personnel. Encourage women to bring their own pillows to make the hospital surroundings more homelike and to facilitate position changes. Environmental modifications should reflect the preferences of the woman, including the number of visitors and availability of a telephone, television, and music.

Labor Support by the Nurse

Supportive nursing care for a woman in labor includes:

• Helping the woman maintain control and participate to the extent she wishes in the birth of her infant

• Providing continuity of care that is nonjudgmental and respectful of her cultural and religious values and beliefs

• Meeting the woman’s expected outcomes for her labor

• Listening to the woman’s concerns and encouraging her to express her feelings

• Acting as the woman’s advocate, supporting her decisions and respecting her choices as appropriate, and relating her wishes as needed to other health care providers

• Helping the woman conserve her energy and cope effectively with her pain and discomfort by using a variety of comfort measures that are acceptable to her

• Helping control the woman’s discomfort

• Acknowledging the woman’s efforts during labor including her strength and courage, as well as those of her partner, and providing positive reinforcement

Women who have attended childbirth education programs that teach the psychoprophylactic (Lamaze) approach will know something about the labor process, coaching techniques, and comfort measures. The nurse plays a supportive role and keeps the woman and her partner informed of the labor progress. If necessary, review the methods learned in class and practiced at home because it may be difficult for the woman to effectively use these methods and techniques now that the woman is in labor and in an unfamiliar setting.

Even when a laboring woman has not attended childbirth classes, the nurse can teach her simple breathing and relaxation techniques during the early phase of labor. In this case the nurse provides more of the coaching and supportive care until the support person feels ready to take on a more active coaching role (see Chapter 17). The nurse can demonstrate comfort measures while encouraging the support person to assist and the laboring woman to express her needs and feelings. Observing the comforting approaches of the nurse can help the partner to learn effective comfort measures.

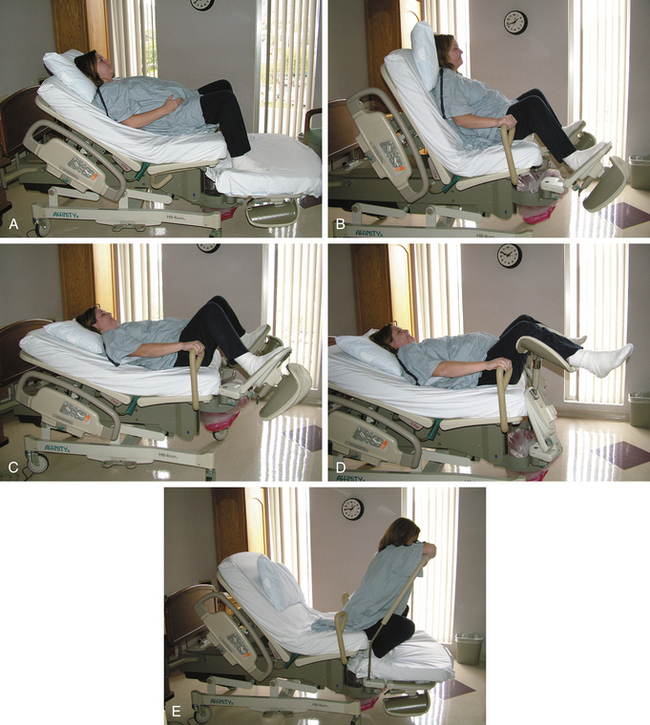

Comfort measures vary with the situation (Fig. 19-14). The nurse can draw on the woman’s list of comfort measures and relaxation techniques learned during the pregnancy and through life experiences. Such measures include maintaining a comfortable, calm, supportive atmosphere in the labor and birth area; using touch therapeutically (e.g., heat or cold applied to the lower back in the event of back labor, a cool cloth applied to the forehead, massage); providing nonpharmacologic measures to relieve discomfort (e.g., hydrotherapy); and most important, just being there (MacKinnon, McIntyre, & Quance, 2005) (see Tables 19-1 and 19-2). See Chapter 17 for a full discussion of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic comfort measures.

FIG. 19-14 Partner providing comfort measures. (Courtesy Marjorie Pyle, RNC, Lifecircle, Costa Mesa, CA.)

Most women in labor respond positively to touch, but you should obtain permission before using any touching measures. Women appreciate gentle handling by staff members. Back rubs and counterpressure may be offered, especially if the woman is experiencing back labor. Teach the support person to exert counterpressure against the woman’s sacrum over the occiput of the head of a fetus in a posterior position (see Fig. 19-12, B). Double hip or knee squeezes can also be helpful in reducing back pain. The back pain is caused by the occiput pressing on spinal nerves, and counterpressure lifts the occiput off these nerves, providing some relief from pain. The partner will need to be relieved after a while, however, because exerting counterpressure is hard work. Hand and foot massage also can be soothing and relaxing.

The woman’s perception of the soothing qualities of touch may change as labor progresses. Many women become more sensitive to touch (hyperesthesia) as labor progresses. This is a typical response during the transition phase (see Table 19-1). They may tell their coach to leave them alone or not to touch them. The partner who is unprepared for this normal response may feel rejected and may react by withdrawing active support. The nurse can reassure him or her that this response is a positive indication that the first stage is ending and the second stage is approaching. Women with increased sensitivity to touch may tolerate it better on surfaces of the body where hair does not grow, such as the forehead, the palms of the hands, and the soles of the feet.

Labor Support by the Father or Partner

Although another woman or a man other than the father may be the woman’s partner, the father of the baby is usually the support person during labor. He is often able to provide the comfort measures and touch that the laboring woman needs. When the woman becomes focused on her pain, sometimes the partner can persuade her to try nonpharmacologic variations of comfort measures. In addition, he usually is able to interpret the woman’s needs and desires for staff members.

The feelings of a first-time father change as labor progresses. Although he is often calm at the onset of labor, feelings of fear and helplessness begin to dominate as labor becomes more active and the father realizes that labor is more work than he anticipated. Capogna, Camorcia, and Stirparo (2007) found that fathers whose partners received epidural analgesia during labor reported less anxiety and stress and more satisfaction with their childbirth experience than fathers whose partners did not. Staff members should tell the father that his presence is helpful and encourage him to be involved in the care of the woman to the extent to which he and his partner are comfortable. He should be reassured that he is not assuming the responsibility for observation and management of his partner’s labor, but that his responsibility is to support her as the labor progresses. The nurse can suggest alternative comfort measures when those he is using are no longer helpful or are rejected by his partner.

The first-time father may feel excluded as birth preparations begin during the transition phase. Once the second stage begins and birth nears, the father’s focus changes from the woman to the baby who is about to be born. The father will be exposed to many sights and smells he may never have experienced. Therefore, the nurse needs to tell him what to expect and to make him comfortable about leaving the room to regain his composure should something occur that surprises him, but make sure that someone else is available to support the woman during his absence.

Nursing actions that support the father convey several important concepts: first, that he is a person of value; second, that he can be a partner in the woman’s care; and third, that childbearing is a team effort. Box 19-6 details ways in which the nurse can support the father-partner. A well-informed father can make an important contribution to the health and well-being of the mother and child, their family interrelationship, and his self-esteem.

Labor Support by Doulas

Continuity of care has been cited by women as a critical component of a satisfying childbirth experience. A specially trained, experienced female labor attendant called a doula can meet this need. The doula provides a continual one-on-one caring presence throughout the labor and birth of the woman she is attending (Pascali-Bonaro & Kroeger, 2004). The primary role of the doula is to focus on the laboring woman and to provide physical and emotional support by using soft, reassuring words of praise and encouragement; touching; stroking; and hugging. The doula also administers comfort measures to reduce pain and enhance relaxation and coping, walks with the woman, helps her to change positions, and coaches her bearing-down efforts. Doulas provide information about labor progress and explain procedures and events. They advocate for the woman’s right to participate actively in the management of her labor.

The doula also supports the woman’s partner, who often feels unqualified to be the sole labor support and may find it difficult to watch the woman when she is experiencing pain. The doula can encourage and praise the partner’s efforts, create a partnership as caregivers, and provide respite care. Doulas also facilitate communication between the laboring woman and her partner, as well as between the couple and the health care team (Simkin & Way, 2008).

Doula support during labor is associated with decreased use of analgesia, decreased incidence of operative birth, increased incidence of spontaneous vaginal birth, and increased maternal satisfaction with the childbirth experience (Berghella et al., 2008).

The roles of the nurse and the doula are complementary. They should work together as a team, recognizing and respecting the role each plays in supporting and caring for the woman and her partner during the childbirth process. The doula provides supportive nonmedical care measures while the nurse focuses on monitoring the status of the maternal-fetal unit, implementing clinical care protocols (including pharmacologic interventions), and documenting assessment findings, actions, and responses (Adams & Bianchi, 2004; Simkin & Way, 2008).

Labor Support by Grandparents

When grandparents act as labor coaches, it is especially important to support and treat them with respect. They may have a way to deal with pain relief based on their experience. Grandparents should be encouraged to help as long as their actions do not compromise the status of the mother or the fetus. The nurse treats grandparents with dignity and respect by acknowledging the value of their contributions to parental support, and by recognizing the difficulty parents have in witnessing the woman’s discomfort or crisis. If they have never witnessed a birth, the nurse may need to provide explanations of what is happening. Many of the activities used to support fathers also are appropriate for grandparents.

Siblings During Labor and Birth

Preparing siblings for acceptance of the new child helps promote the attachment process and may help the older children accept this change. The older child or children who know themselves to be important to the family become active participants. Rehearsal for the event before labor is essential.

The age and developmental level of children influence their responses; therefore, preparation for the children to be present during labor is adjusted to meet each child’s needs. The child younger than 2 years shows little interest in pregnancy and labor. However, for the older child, such preparation may reduce fears and misconceptions. Parents need to be prepared for labor and birth themselves and feel comfortable about the process and the presence of their children. Most parents have a “feel” for their children’s maturational level and their physical and emotional ability to observe and cope with the events of the labor and birth process. Preparation can include a description of the anticipated sights, events (e.g., ROM, monitors, IV infusions), smells, and sounds; a labor and birth demonstration; a tour of the birthing unit; and an opportunity to be around a real newborn. Storybooks about the birth process can be read to or by children to prepare them for the event. Films are available for preparing preschool and school-age children to participate in the labor and birth experience. Children must learn that their mother will be working hard during labor and birth. She will not be able to talk to them during contractions. She may groan, scream, grunt, and pant at times as well as say things she would not say otherwise (e.g., “I can’t take this anymore,” “Take this baby out of me,” or “This pain is killing me”). You can tell them that labor is uncomfortable, but that their mother’s body is made for the job.

Most agencies require that a specific person be designated to watch over the children who are participating in their mother’s childbirth experience, to provide them with support, explanations, diversions, and comfort as needed. Health care providers involved in attending women during birth must be comfortable with the presence of children and the unpredictability of their questions, comments, and behaviors.

Second Stage of Labor

The second stage of labor is the stage in which the infant is born. This stage begins with full cervical dilation (10 cm) and complete effacement (100%) and ends with the baby’s birth. The force exerted by uterine contractions, gravity, and maternal bearing-down efforts facilitates achievement of the expected outcome of a spontaneous, uncomplicated vaginal birth. The median duration of second stage labor is 50 minutes in nulliparous women and 20 minutes in multiparous women. In addition to parity, maternal size and fetal weight, position, and descent influence the length of this stage. The use of epidural anesthesia during labor often increases the length of the second stage of labor because the epidural blocks or reduces the woman’s urge to bear down and limits her ability to attain an upright position to push. The upper limits for the duration of normal second stage labor are (Battista & Wing, 2007):

A prolonged second stage is diagnosed after these time limits are reached, a thorough assessment of the status of the maternal fetal unit should be made as well as a determination regarding the likely effectiveness and safety of further bearing-down efforts (Simpson et al., 2008).

The second stage of labor is composed of two phases: the latent phase and the active pushing (descent) phase. Maternal verbal and nonverbal behaviors, uterine activity, the urge to bear down, and fetal descent characterize these phases (Hanson, 2009; Simpson et al., 2008).

The latent phase is a period of rest and relative calm (i.e., “laboring down”). During this early phase the fetus continues to descend passively through the birth canal and rotate to an anterior position as a result of ongoing uterine contractions. The woman is quiet and often relaxes with her eyes closed between contractions. The urge to bear down is not strong and some women do not experience it at all or only during the acme (peak) of a contraction. Allowing a woman to rest during this phase, and waiting until the urge to push intensifies, reduces maternal fatigue, conserves energy for bearing-down efforts, and provides optimal maternal and fetal outcomes (Simpson, 2005). Although delayed pushing is associated with a longer second stage of labor, it results in a significantly higher incidence of spontaneous vaginal birth. Other benefits of delayed pushing include less FHR decelerations, fewer forceps- and vacuum-assisted births, and less perineal damage (lacerations and episiotomies). Careful monitoring with assurance of normal fetal status should be used during delayed pushing. If descent is slow and the woman becomes anxious, she should be encouraged to change positions frequently or to stand by the bedside to use the advantage of gravity and movement to facilitate descent and progress to the active pushing phase signaled by a perception of the need to bear down (Hanson, 2009). The longer length of second stage labor is not associated with poor neonatal outcome, as long as the fetal status during this time is normal (Berghella et al., 2008; Brancato, Church, & Stone, 2008; Roberts & Hanson, 2007; Simpson & James, 2005).

During the phase of active pushing (descent) the woman has strong urges to bear down as the Ferguson reflex is activated when the presenting part presses on the stretch receptors of the pelvic floor. At this point, the fetal station is usually +1 and the position is anterior. This stimulation causes the release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary gland, which provokes stronger expulsive uterine contractions. The woman becomes more focused on bearing-down efforts, which become rhythmic. She changes positions frequently to find a more comfortable pushing position. The woman often announces the onset of contractions and becomes more vocal as she bears down. The urge to bear down intensifies as descent progresses and the presenting part reaches the perineum. The woman may be more verbal about the pain she is experiencing; she may scream or swear and may act out of control.

The nurse encourages the woman to “listen” to her body as she progresses through the phases of the second stage of labor. When a woman listens to her body to tell her when to bear down, she is using an internal locus of control and often feels more satisfied with her efforts to give birth to her baby. This enhances her sense of self-esteem and accomplishment and her efforts become more effective. Always encourage the woman’s trust in her own body and her ability to give birth to her baby. Validate the woman’s experience of pressure, stretching, and straining as normal and a signal that the descent of the fetus is progressing and that her body is capable of withstanding birth. Honestly explain what is happening and describe the progress being made.

Care Management

The only certain objective sign that the second stage of labor has begun is the inability to feel the cervix during vaginal examination, indicating that the cervix is fully dilated and effaced. The precise moment that this occurs is not easily determined because it depends on when a vaginal examination is performed to validate full dilation and effacement. This makes timing of the actual duration of the second stage difficult. Other signs that suggest the onset of the second stage include the urge to push or feeling the need to have a bowel movement. These signs commonly appear at the time the cervix reaches full dilation. However, they can appear earlier in labor. Women with an epidural block may not exhibit such signs.