5 Hydrolats – the essential waters

Introduction

The subject of aromatic waters is intriguing, yet not one on which very much has been written. It has been necessary to search many books on herbalism and aromatherapy to glean snippets of information. Even then the quality of information is not always very good, and very little would stand up to rigorous examination (save for the information on kekik water (Aydin, Baser & Öztürk 1996)). Most has been found in the French literature, as France is the country that most uses hydrolats, although even there not to a great extent today.

Water has the remarkable capability of picking up information relating to the vibrational energy found in a living plant, of storing this information and, under certain circumstances, of transferring it to the human body. This means that distilled hydrolats pick up and store not only physical plant particles (Roulier 1990) but possibly also subtle energetic information; consequently, such products have an almost homoeopathic aspect.

There are several kinds of water-based aromatic product used in therapies, including infusions, teas (it has been estimated that over 1 000 000 cups of chamomile tea are taken every day worldwide (Foster 1996)), tisanes, wines, vinegars and aromatic waters, which may be distilled or prepared. Distilled aromatic waters – hydrolats – contain the water-soluble compounds of the plant, but not the tannic acid and bitter substances, and make an excellent complement to that other product of distillation, the powerful essential oils. They are, however, very different in nature from the volatile essential oils, albeit obtained from the same plant, in as much as they are without aggression and are active on a different level; these ‘gentle giants’ are subtle, safe and effective, although any treatment must be carried out over a longer period of time than when using essential oils.

Some plants, whether containing essential oils or not, are distilled specifically for the hydrolat and not for the essential oil; when plants are distilled specifically for the hydrolat the quality of the water used is of great importance. Although there may be no volatile or aromatic molecules in these plants, and hence no aromatic oil, all water-soluble molecules within the plant are taken up by the steam; thus the hydrolats stand intermediate between, and to some extent represent a fusion of, aromatherapy and herbalism, containing as they do some of the useful plant molecules from both worlds. Hydrolats are used in conjunction with both essential oil treatments and herbalism, as well as on their own.

As these valuable products of the distillation process are so safe in use, they deserve to be much better known and far more widely used, especially by aromatherapists already familiar with the essential oils. Hydrolats last featured in the French Codex in 1965.

Terminology

In France the term hydrolat is used to describe the condensed steam which has passed through the plant material; the translation of hydrolat is given as ‘aromatic, medicated water’ (Mansion 1971) and this is the nomenclature adopted by Price and Price (2004 p. 31–34) to describe distilled plant waters, but many names are in use, some more accurate than others.

Terms used for these products are:

• Aromatic water – this term does not imply distillation and so is inaccurate.

• Floral waters – this is inaccurate and incomplete, as by no means all distilled waters are from flowers.

• Hydrosol – this is inappropriate, as it is a generic term applied to a wide range of products (including hydrolats) and is not specific: a hydrosol may be defined as a colloidal solution (i.e. a dispersion of material in a liquid, characterized by particles of very small size, of between 0.2 and 0.002 μm) where water is the dispersant medium.

• Essential water – this is an ancient name and aptly describes the aromatic distilled water from the still.

• Prepared water – this is an assembly of products to simulate a natural product.

Prepared aromatic waters

These are not produced by the distillation process but are put together in a laboratory. They consist of distilled water with the addition of one or more essential oils; these oils may be genuine plant extracts (volatile oil, absolute or concrete) or they may be partly or wholly artificial or synthetic. Essential oils are not generally soluble in water – probably on average only about 20% of any given oil is water soluble – but many can be ‘knocked’ into solution by shaking to produce a saturated solution. For each litre of distilled water 2–3 g (40–60 drops) of essential oil can be added; this must be shaken frequently and vigorously for 2 or 3 days and then stored in a cool place; it can be stored successfully at 10–15°C for several months. Essential oils suitable for use by this method are anise, basil, Borneo camphor, caraway, chamomile, cinnamon, citron, coriander, cypress, eucalyptus, fennel, garlic, geranium, hyssop, juniper, lavender, lemon, marjoram, melissa, niaouli, nutmeg, orange, origanum, peppermint, rosemary, sage, savory, tangerine, tarragon, verbena and ylang ylang (Lautié & Passebecq 1979 p. 91).

Prepared waters may be used for gargles, mouthwashes, bathing wounds and for ingestion, where 20 mL of the made water contains one drop of essential oil and therefore one teaspoonful contains about a quarter of a drop (about 0.25% concentration). Many essential oils exhibit significant bactericidal power at a concentration of 0.25%, as found in prepared waters, e.g. in a concentration of 0.18% clove essential oil kills the tubercle bacillus in a few minutes without causing any tissue damage or risk of toxicity, in contrast to some other preparations and antibiotics (Lautié & Passebecq 1979 p. 92).

Prepared waters do not have the same make-up as essential (distilled) waters, and therefore cannot have the same therapeutic properties. Some prepared waters are made with alcohol, and these are not recommended for use alongside aromatherapy. The main volume of sales of prepared waters is to skincare manufacturers for use in ‘natural’ skin toners, refreshers and washes. Water which has had essential oil(s), synthetics or alcohol added to it is not a hydrolat, and the two should not be confused. To achieve a genuine plant water, distillation alone is the true method.

What are hydrolats?

Hydrolats are a product of distillation and can be considered as true partial extracts of the plant material from which they are derived. They may be byproducts of the distillation of volatile oils, e.g. chamomile water and lavender water, or of the distillation of plant material which has no volatile oil, e.g. elderflower, cornflower, plantain. Their method of preparation, by definition, necessitates that they be totally natural products with no added synthetic fragrance components. Hydrolats are obtained from aromatic and other plants by steam distillation, and during this process a proportion of the water-soluble compounds of the essential oil contained in the plant matter is absorbed by and retained in the water. As some essential oils have a relatively high proportion of water-soluble compounds, much of the essential oil can be lost to the water during the distillation process, e.g. Melissa officinalis [lemon balm]; in such cases it is imperative to use cohobation. This is a system whereby the water/steam in contact with the biomass during distillation is continuously recirculated, giving maximal opportunity for the water-soluble elements of the essential oil and the plant to pass into the water. Eventually this water reaches saturation point, when no more of the essential oil components can pass into solution (it is at this stage that the complete essential oil is gained); thus a water is produced that is rich not only in some essential oil molecules but also in other hydrophilic molecules found in the plant which are not usually part of the essential oil. When distilling for hydrolats, it is important that the water used in the distillation process should be of good quality, preferably from a non-polluted spring, and free of any chemical cleansers that may have been used to clean the still.

Aromatic waters contain about 0.02–0.05% (or perhaps more, depending on the plant) of the water-soluble parts of the essential oil freely dispersed in an ionized form; this is equivalent to up to approximately 10 drops per litre of hydrolat (Price & Price 2004 p. 47). They may have similar properties to the parent oils but not to the same degree, and often their properties are different.

Which plants yield a hydrolat?

Many aromatherapists think that only plants containing an essential oil are distilled, but this is not so. Many plants containing very little or no essential oil at all are processed, primarily to gain the hydrolat. The hydrolat from each plant, like the essential oil, is unique and reacts according to its constituents. Hypericum perforatum, often macerated in olive oil to obtain its therapeutic properties (see Carrier oils in Ch. 8), is an example of a plant that contains an essential oil but which is rarely distilled for this on account of the minute yield, which would cause the price to be prohibitive; it is therefore distilled for its hydrolat. Plantago lanceolata [plantain] is an example of a non-aromatic plant which is distilled only for its hydrolat. This illustrates that water-soluble molecules other than volatile essential oil molecules can be taken into the steam, yielding a therapeutic water at the end of the process.

Yield

It is not possible to obtain an almost unlimited or even a large quantity of water from a small amount of plant material. The quantity of hydrolat is proportionately limited to the plant weight, and therefore hydrolats of excellent quality are obtained when cohobation is an integral part of the distilling process. This method is used to produce a number of hydrolats, e.g. rose, and yields a saturated hydrolat; Melissa is another case where a whole essential oil cannot be achieved until the steam water is saturated with the water-soluble molecules of the essential oil, thereby preventing the loss of these from the essential oil.

Yields of distilled waters usually lie between the limits of 1–1.5 and 2–5 L/kg of plant matter, and vary according to the particular plant. The waters of thyme, savory and rosemary require a smaller quantity of plant than do waters of lettuce, hawthorn, yarrow or hemp agrimony. Some waters are known as ‘weight for weight’ products, as the quantities of plant matter and water product are equal, e.g. 100 lb of roses are distilled with sufficient water to yield 100 lb of fragrant rose water (Poucher 1936).

Appearance and aroma

Distilled waters are not strongly coloured and are clear, with the exception of cinnamon water, which is always opalescent; for the most part they have only slight, delicate coloration (Viaud 1983 p. 23). Their smell may be generally reminiscent of the original plant material, but this is not always the case; an example is distilled lavender water, which often disappoints (Price & Price 2004 p. 58–59)

Keeping qualities and storage

Waters need to be stored at a temperature of less than 14°C, and in the shade. At higher temperatures certain waters tend to show flocculation. The maximum storage period under the conditions given must not, in general, exceed 1 year, as some hydrolats are fragile and break down after a relatively short time. They are best purchased in small quantities, although Rouvière and Meyer (1989) say that the plant waters resulting from the distillation process of essential oils have a life of 2–3 years, owing to the presence of soluble compounds from the essential oils, which inhibit bacterial growth: this has been confirmed by the authors (Price & Price 2004 p. 56–57). Those hydrolats that have a good content of antiseptic phenols keep well; the distilled waters of Satureia hortensis and Origanum vulgare can be kept for more than 2 years with no discernible change.

Composition

It is known that, besides certain volatile compounds (isovalerianic, cyanhydric, benzoic and cinnamic acids), distilled plant waters can contain many other volatile principles, although these are rarely properly identified. Analysis of three hydrolats (Lavandula angustifolia, Salvia officinalis, Matricaria recutita) showed that they contain substances present in the plant (Montesinos 1991 p. 24, Price & Price 2004). The pH of a hydrolat is closely linked to the concentration of alcohols and phenols present and to the degree of dissociation; they are sometimes neutral, but usually have a weak acid reaction (Price & Price 2004 p. 58).

Quality

The basic criteria for obtaining a good-quality hydrolat are the same as those for the procurement of a genuine essential oil, i.e. using a known botanical species, grown organically or wild, with a known chemical make-up; a distillation of sufficient duration and at low pressure; and a hydrolat that itself has had nothing added and nothing extracted. It is imperative that only products obtained during steam distillation and without colouring matter, stabilizers and preservatives be used. Products procured from a high-street chemist’s shop do not usually conform to this high standard, often containing synthetic materials; alternatively, they may be entirely artificial.

As with an essential oil, it is difficult to judge the quality of a distilled water from the smell: a true distilled water does not necessarily smell the same as the oil from the same plant because it has a different chemical make-up; when freshly distilled it may have an odour and taste of the still, although this is not long lasting.

Unfortunately, most hydrolats from plants distilled for their essential oils are discarded, and are saved only if ordered beforehand. It is generally thought that because hydrolats are often thrown away, they should be inexpensive; unhappily this is not the case, as the cost of transporting the bulk (volume and weight) of the product is reflected in the final cost.

Uses of hydrolats

A nice attention, however, is certainly necessary in the use of them.

John Farley (1783), principal cook at the London Tavern, Dublin, referring to the water and infusions of bay.

Waters are ultramild in action compared to essential oils and are useful for the treatment of the young, the elderly, and those in a state of delicate health. The less volatile odorous molecules are integrally dispersed in the water in ionized form, therefore irritation of the skin and mucous surfaces is avoided. Hydrolats have a higher concentration of volatile elements than do teas and so are more efficacious and quicker acting, with a very easy method of use, i.e. drinking small quantities.

Hydrolats work synergistically with essential oils and so they can be prescribed as a complement to either phytotherapy (Streicher 1996) or aromatherapy. Herbalists in France do not use these waters on their own to any great extent, but they are used as a complement to other phytotherapeutic treatments, both internally and externally; they are used both singly and as ready-prepared mixes.

General

Being non-aggressive, waters can be used safely for disinfection of open wounds and on mucous surfaces; they have been mentioned for use in cases of eczema, ulcers, bronchitis, tracheitis, colitis, burns and pain, whether local or generalized (e.g. Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile] is said to ease post-zoster pain). They are used in gargles, nasal sprays, skin sprays, compresses and vaginal douches.

Skin care

Hydrolats are nearly free of irritating components, and their mild action and lack of toxicity make them ideal for use as skincare products; they have long

Client assessment

One day, when Harry, 36, lit a ring on his gas stove, the whole space exploded into flames, burning his face and neck. Although he managed to put some cold water on his face, he had to extinguish the fire and comfort his four children. The aromatherapist arrived half an hour after the burning occurred and Harry was in great pain. The hospital was over 25 km away, the burn needed immediate treatment, and Harry was reluctant to go to the hospital anyway.

Intervention

Day 1 – afternoon: Burnt hair was sticking to Harry’s face and neck and he was in shock. First, he was asked to stand in the shower for 10 minutes with cold water pouring over his face and neck. Meanwhile, three basins were prepared as follows:

1. Ice cubes, 200 mL of lavender hydrolat (Lavendula officinalis– all the therapist had with her) and 50 mL of peppermint hydrolat (Mentha x piperita) to help cool the skin.

2. 0.5 L of cold water, 5 mL lavender essential oil and 50 mL of peppermint hydrolat.

• A clean teatowel was torn in half, wrung into basin 1 (keeping it fairly wet) and applied to Harry’s face and neck.

• The second piece was dipped into basin 2 and applied; these two applications were repeated many times, as the towel immediately turned warm on his burn. Ice cubes were continually added to the first and second basins – plus another 50 mL peppermint hydrolat to basin 1 and another 5 mL lavender essential oil to basin 2.

This went on for 2 hours, during which time Harry was given a strong painkiller.

As the skin had cooled down somewhat, the following gel was prepared and thickly but very gently applied to the whole area:

• 25 mL fresh aloe vera (direct from the plant)

• 10 drops Lavandula officinalis– analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, cicatrizant

• 20 drops Melaleuca alternifolia [tea tree] – analgesic, anti-infectious, anti-inflammatory

Harry felt immediate relief and after 5–10 minutes the pain lessened. After 1 hour the gel had formed a strong film (stronger than that on healthy skin) and the pain was gone.

His eyes and lips were very swollen, his face red, and on his upper lip blisters were forming where he had licked off the gel. More was applied there, after which Harry went to bed and slept soundly.

Day 2 – morning: The whole face was sore, the nose having an open wound where the skin was burned off. It was not bleeding, although it was weeping and swollen. There were brown dry patches under his eyes, his eyelids were swollen and red, his lips swollen and cracked, and his cheeks streaked in red and white.

The whole area was sprayed with rose hydrolat (Rosa damascena), a very wet compress was made with the hydrolat to try and help remove the burnt hair still stuck on his skin. When it was removed and the skin was dry the gel blend was applied again to the whole face, upper lip and neck. Photographs were taken.

Day 2 – evening: During the day the brown patches had paled somewhat. His chin and neck were still painful. The nose had dried up and a scab was forming around the edges of the wound. Harry had slept during the day.

The spraying and compress treatments were repeated with the rose hydrolat, and more burnt hair came away. As the emergency was over, a weaker gel blend was then made, using 25 mL aloe vera gel with only 5 drops each of Lavandula officinalis and Melaleuca alternifolia.

Day 3 – morning: The skin was cleansed again with rose hydrolat to remove the last of the burnt hair; the nose and lip had started to dry up, the area was less swollen and the patches under the eyes were almost gone. The whole area was still sensitive.

Day 3 – evening: The nose and lip had started bleeding slightly, but as the face and neck showed only a faint redness by then, the gel blend was applied only to the nose and lip, and carrot oil, which is anti-inflammatory and helpful to burns, to the rest of the area.

Day 4 – morning: This was the turning point! No pain, only itching. Harry’s nose and lip had small scabs and looked clean, with no suggestion of impending infection. A doctor representing the insurance company arrived and said that the nose and lip had second-degree burns, the face and neck first-degree. He did not believe the burn had been as bad as reported, until he was shown the photographs.

Harry took a lukewarm shower, the gel dissolving in the water. Carrot oil was then applied to the whole area except the nose and lip, which was given the gel blend again. The procedure was repeated in the evening.

been used in this way in the form of cleansers, toners (all skin types, especially sensitive skin), conditioning creams and lotions. They are also used in baby care, bath preparations, hair rinses, aftershave preparations and facial sprays.

Children

Hydrolats produced for therapeutic use should not contain added alcohol as a preservative and so are suitable for children, especially as they may be sweetened with honey or sugar. They are recommended for young children for both external and internal use because they do not irritate the skin or mucous surfaces (note: care must be taken when procuring the hydrolat: concentrated waters do contain alcohol (Price & Price 2004 p. 38)).

Eye care

Some hydrolats are used in preparations for eyewashes, e.g. Myrtus communis [myrtle], Centaurea cyanus [cornflower] and Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile] soothe pains resulting from inflammatory states in the eyes.

Traditional medicine

Hydrolats are often prescribed by some complementary practitioners to adjust the ‘energy balance’ and the ‘environment’ (both internal and external) of the person, for instance according to Chinese medicine. The conditions treated include disorders of the digestive system such as constipation; rheumatism, migraine (from liver irritation), parasites, and ear, nose and throat problems.

Routes of absorption

First there is the oral route through the walls of the digestive tract. The culinary aspect is attractive here, as hydrolats are easily added to foods and are palatable (Price & Price 2004 pp. 173–177).

The rectal route using an enema is also used, and the active substance is here absorbed across the mucous surfaces of the large intestine.

Finally there is the skin; here the substance is absorbed from the whole surface of the body.

Methods of use and dosages

• Put 50 mL of hydrolat into a bath to aid relaxation and promote a soothing effect.

• Use it on a cottonwool pad as a skin tonic after cleansing.

• Use it as a mouthwash or gargle.

• Put a teaspoonful (5 mL) into tea (without milk), fruit juice or fruit salads, coffee (petitgrain or orange flower water is delicious in coffee and fruit salads) or in a morning glass of water.

• Oral (internal) use may safely be recommended where appropriate; up to three teaspoonfuls (15 mL) per day may be ingested.

The duration of treatment is dependent on the particular organ and person being treated:

• For treatment of the liver, two teaspoonfuls should be taken before supper or before going to bed.

• For treatment of the kidneys and bladder, three teaspoonfuls should be taken between 3 pm and 7 pm.

• For treatment of the lungs, six teaspoonfuls should be spread throughout the day in acute cases, or three teaspoonfuls for chronic cases.

• For gargles hydrolats may be used neat, but in general use they should be diluted, up to 1 in 10 depending on the water.

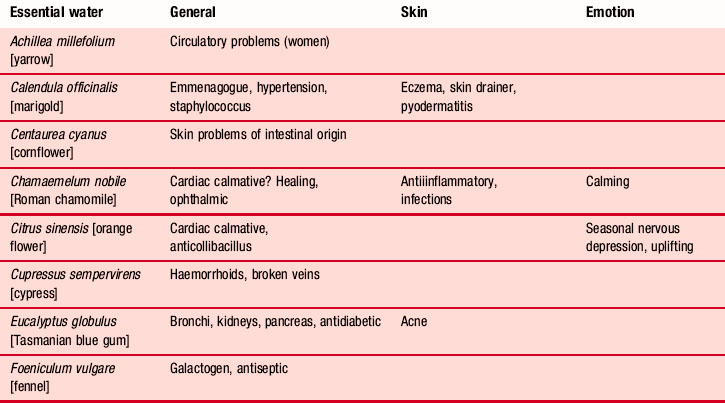

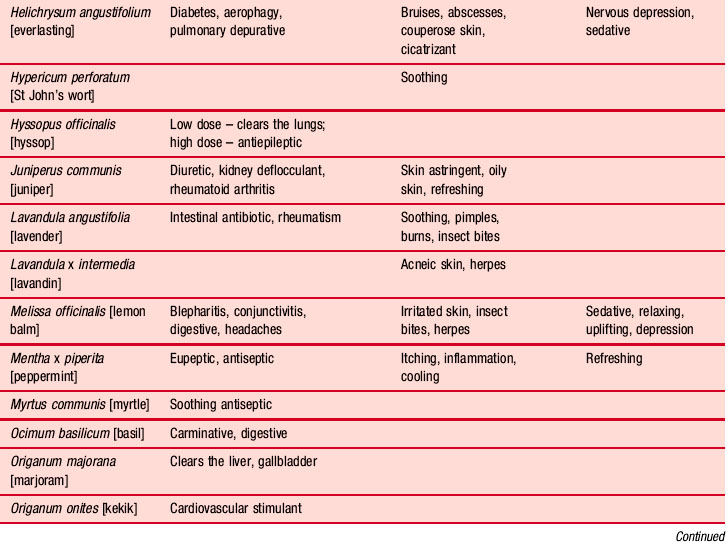

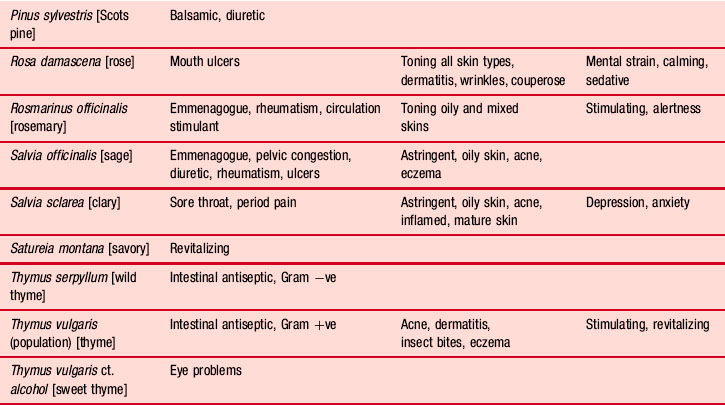

Table 5.1 lists the properties and indications for the use of hydrolats for general conditions, skin conditions and emotional states: in the absence of any other kind of proof these are based almost wholly on anecdotal evidence. There is a general table giving the properties of these waters in Price and Price (2004). Waters have certainly been in continual use for three and a half centuries, and perhaps longer, in cooking, for medicine and for personal cleanliness (Genders 1977).

Cautions

It should be noted that preservative is often added to shop-bought natural hydrolats to improve their shelf-life, and these should be avoided for culinary or therapeutic purposes. When purchasing waters it may also be necessary to obtain a certificate from the supplier to ensure that the proper conditions of harvesting, processing and stocking have been observed.

Like other partial plant extracts, hydrolats will possess the claimed activity of the plant only if its constituents giving this activity are contained within that fraction of the plant forming the partial extract. Many partial plant extracts, particularly distillates, have the advantage of being virtually colourless, making them easy to incorporate into a range of products. Unfortunately, over the years this has led to the production of distillates from a wide range of plant materials which are not suitable for this form of processing, and

Case study 5.2 Menopausal problems

Client assessment

Norma, aged 52, suffered from menopausal symptoms, such as sleepless nights, hot flushes and restless legs. Occasionally she had migraines or severe headaches. She felt tired all the time and was forgetful. The worst symptom was the flushing, which Norma had been suffering from for over 4 years, the problem being so severe that during that time she had not been able to have a cover on her, otherwise she woke up drenched with sweat, needing to change the bed.

Intervention

After a thorough consultation, the following was advised:

• Cut down on processed foods and alcohol.

• Walk rather than drive whenever possible.

• Go to her GP for a thyroxin level check – this can fall during menopause, thereby being a contributory factor to tiredness, memory loss and headaches.

The following hydrolats were blended together 50/50:

Both are beneficial for menopausal symptoms, in particular hot flushes, and help to balance the natural hormone levels in the body. Norma was asked to drink 25 mL of this three times a day, in 25 mL warm water, and to contact the therapist in 7 days to let her know how she was coping. She was also reminded about starting her lifestyle changes.

Outcome

After 5 days an excited Norma phoned to say that she had just had her first good night’s sleep for years, and that she had slept with a sheet over her. She was delighted and amazed that the hydrolats had worked so quickly – as was the therapist! She had not had time to make any serious lifestyle changes – just increase her walking time and practise deep breathing.

Within the month, her intake of hydrolats was reduced to twice a day and the next month to once a day, by which time Norma was sleeping with a duvet and the headaches had notably improved.

Norma enjoyed the taste and was happy to continue the treatment, which she is still on at the time of writing.

Her thyroid test showed that she needed slight supplementation, and within 3 months her tiredness had improved.

therefore little credence can be given to any claimed activity of the plant material or to its extract (Helliwell 1989).

Summary

Continued use of hydrolats over centuries indicates that these substances have a potential for therapeutic use and are worthy of investigation. Physically they contain some water-soluble molecules known to be therapeutic, in common with essential oils and some compounds found in other types of herbal preparation, and it may be that they also carry information and energy in a manner somewhat analogous to homoeopathic remedies. They are gentle in use and may safely be used in some cases where the use of the more powerful essential oils would be inadvisable, and may also be used to complement other forms of treatment; they have the advantage of being relatively inexpensive.

Aydin B., Öztürk. The chemistry and pharmacology of origanum (kekik) water. 27th International Symposium on Essential Oils. 1996. September, Vienna

Farley J. Handbook on the art of cookery and housekeepers complete assistant. 1783:307.

Foster S. Chamomile: Matricaria recutita & Chamaemelum nobile. In: Botanical series 307. Austin: American Botanical Council; 1996:6.

Genders R. A book of aromatics. London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1977;13.

Helliwell K. Manufacture and use of plant extracts. In: Grievson M., Barber J., Hunting A.L.L., editors. Natural ingredients in cosmetics. Micelle: Weymouth; 1989:26-27.

Lautié R., Passebecq A. Aromatherapy; the use of plant essences in healing. Wellingborough: Thorsons, 1979.

Mansion J.E. Harrap’s new standard French and English dictionary. 1971.

Montesinos C. Eléments de reflexion sur quelques hydrolats. Lyons: Study written for Ecole Lyonnaise de Plantes Médicinales, 1991.

Poucher W.A. Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps. London: Chapman & Hall; 1936;II:34-35.

Price L., Price S. Understanding hydrolats: the specific hydrosols for aromatherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Roulier G. Les huiles essentielles pour votre santé. St-Jean-de-Braye: Dangles, 1990;115.

Rouvière A., Meyer M.-C. La santé par les huiles essentielles. Paris: M A Editions, 1989;82-83.

Streicher C. Hydrosols – the subtle complement to essential oils. Plexus. 1996;1:22.

Viaud H. Huiles essentielles – hydrolats. Sisteron: Présence, 1983.

Claeys G. Précis d’aromathérapie familiale. Flers: Equilibres, 1992;74.

de Bonneval P. Votre santé par les plantes. Flers: Equilibres, 1992.

Grace U.-M. Aromatherapy for practitioners. Saffron Walden: Daniel, 1996;84-85.

Price S. Aromatic water. The Aromatherapist. 1997;3(2):44-47.

Price L., Price S. Essential waters. Stratford upon Avon: Riverhead, 1999.

Rose J. Hydrosols: the other product of distillation. California: Aromatherapy correspondence course notes, 1994.