Bacterial infection – Staphylococcal and streptococcal

The skin is a barrier to infection but, if its defences are penetrated or broken down, numerous micro-organisms can cause disease (Table 1).

Table 1 Bacterial diseases of the skin

| Organism | Infection |

|---|---|

| Commensals | Erythrasma, pitted keratolysis, trichomycosis axillaris |

| Staphylococci | Impetigo, ecthyma, folliculitis, secondary infection |

| Streptococci | Erysipelas, cellulitis, impetigo, ecthyma, necrotizing fasciitis |

| Gram-negative | Secondary infection, folliculitis, cellulitis |

| Mycobacterial | TB (lupus vulgaris, warty tuberculosis, scrofuloderma), fish tank granuloma, Buruli ulcer, leprosy |

| Spirochaetes | Syphilis (e.g. primary, secondary), Lyme disease (erythema chronicum migrans) |

| Neisseria | Gonorrhoea (pustules), meningococcaemia (purpura) |

| Others | Anthrax (pustule), erysipeloid (pustule) |

The normal skin microflora

Normal skin has a resident flora of usually harmless micro-organisms, including bacteria, yeasts and mites. The bacteria are mostly staphylococci (e.g. Staphylcoccus epidermidis), micrococci, corynebacteria (diphtheroids) and propionibacteria. They cluster in the stratum corneum or hair follicles, and their number varies between individuals and between different sites on the body. Micrococci, for example, number 0.5 million/cm2 in the axilla but only 60/cm2 on the forearm. Some individuals are high carriers.

Staphylococcal infections

A third of people intermittently carry Staphylococcus aureus in the nose or, less often, the axilla or perineum. Staphylococci can infect the skin directly or secondarily, as in eczema or psoriasis.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a contagious superficial skin infection caused by either staphylococci or streptococci, or both.

Clinical presentation

Impetigo is now relatively uncommon in the UK, mainly because of improved social conditions, but it is endemic in developing countries. It generally occurs in children and presents as thin-walled, easily ruptured vesicles, often on the face, which leave areas of yellow-crusted exudate (Fig. 1). Lesions spread rapidly and are contagious. A bullous form, with blisters 1–2 cm in diameter, is seen in all ages and affects the face or extremities. Atopic eczema, scabies, herpes simplex and lice infestation may all become impetiginized. Impetigo can be confused with herpes simplex or a fungal infection.

Management

Most localized cases respond to the removal of the crusts with saline soaks and the application of a topical antibiotic (e.g. mupirocin, fusidic acid or neomycin/bacitracin). Systemic flucloxacillin or erythromycin is given for widespread infection. Impetigo caused by Streptococcus pyogenes may result in glomerulonephritis, a serious complication. Methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) carriage (and infection) has increased with the widespread use of antibiotics.

Ecthyma

Ecthyma is characterized by circumscribed, ulcerated and crusted infected lesions that heal with scarring. An insect bite or neglected minor injury may become infected with staphylococci or streptococci (or both). Ecthyma mostly occurs on the legs (Fig. 2) and may be seen in drug addicts or debilitated patients. Treatment is with systemic and topical antibiotics.

Folliculitis and related conditions

Infection can affect hair follicles. Folliculitis is an acute pustular infection of multiple hair follicles; a furuncle is an acute abscess formation in adjacent hair follicles; and a carbuncle is a deep abscess formed in a group of follicles giving a painful suppurating mass.

Clinical presentation

Follicular pustules are seen in hair-bearing areas, e.g. the legs, scalp or face. In men, folliculitis may affect the beard area (sycosis barbae). In women, it may occur on the legs after hair removal by shaving or waxing. Staph. aureus is usually, but not invariably, responsible. Strains carrying the virulence factor Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) are associated with more aggressive disease. A Gram-negative folliculitis (e.g. with Pseudomonas) may occur with prolonged antibiotic treatment for acne. Pityrosporum folliculitis is a separate condition due to a commensal yeast (p. 38).

Furuncles (boils) present as tender red pustules that suppurate and heal with scarring. They often occur on the face, neck, scalp, axillae and perineum. Some patients have recurrent staphylococcal boils of the axillae or perineum. Large suppurating carbuncles (Fig. 3) due to Staph. aureus may cause systemic upset.

Management

Swabs for bacterial culture are taken from the lesion and from carrier sites, e.g. the nose, axilla and groin. Obesity, diabetes mellitus and occlusion from clothing are predisposing factors. Acute staphylococcal infections are treated with antibiotics, both systemic (e.g. flucloxacillin or erythromycin) and topical (e.g. fusidic acid, mupirocin or neomycin/bacitracin). Chronic and recurrent cases are more difficult. Carrier sites, e.g. the nose, need treatment with a topical antibiotic (e.g. mupirocin). General measures such as improved hygiene, regular bathing or showering, the use of antiseptics in the bath and on the skin (e.g. chlorhexidine) can help, but courses of oral antibiotics may be needed. Carbuncles often need prompt surgical drainage. An infrequent complication is thrombosis in the cavernous sinus, associated with facial infection.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is an acute toxic illness, usually of infants, in which there is shedding of sheets of epidermis associated with localized staphylococcal infection in the skin or elsewhere. Large sheets of superficial epidermis are shed, resembling a scald, leaving denuded erythematous areas. Phage group II staphylococci release into the bloodstream epidermolytic toxins, which cause the epidermis to split. A related condition in adults with the same level of epidermal split is pemphigus foliaceus (p. 87).

Although a serious condition requiring inpatient treatment, the prognosis is good when systemic flucloxacillin or erythromycin is prescribed.

Streptococcal infections

Strep. pyogenes, the principal human skin pathogen, is occasionally found in the throat and may persist after an infection. It is sometimes carried in the nose and can contaminate and colonize damaged skin.

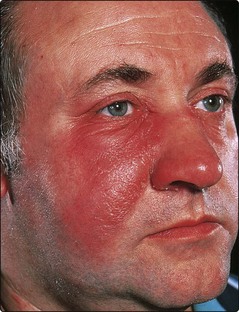

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is an acute infection of the dermis by Strep. pyogenes. It shows well-demarcated raised erythema, oedema and skin tenderness.

Clinical presentation

The skin lesions may be preceded by fever, malaise and ‘flu-like’ symptoms. Erysipelas usually affects the face (where it may be bilateral) or the lower leg, and appears as a painful hot red swelling (Fig. 4). The lesion has a well-defined edge and may blister. Cellulitis may coexist. The streptococci usually gain entry to the skin via a fissure, e.g. behind the ear, or associated with tinea pedis between the toes.

Differential diagnosis and complications

On the face, erysipelas may be confused with angioedema or allergic contact dermatitis, but the condition is usually distinguishable as it causes tenderness and systemic upset. Recurrent attacks in the same place can result in lymphoedema due to lymphatic damage. A fatal streptococcal septicaemia can occur in debilitated patients. Guttate psoriasis (p. 28) and acute glomerulonephritis may follow a streptococcal infection.

Management

A good response is usually seen with prompt treatment. Topical therapy is inappropriate, and penicillin should be prescribed. Strep. pyogenes is nearly always sensitive. Intravenous treatment is needed at first for a severe infection, usually with benzylpenicillin for about 2 days. Oral penicillin V can then be given for 7–14 days. In less severe cases, penicillin V is adequate. Erythromycin is used if there is penicillin allergy. Recurrent erysipelas, i.e. more than two episodes at one site, requires prophylactic long-term penicillin V (250 mg once or twice a day), with attention to hygiene at potential portals of entry.

Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis is an acute and serious infection. It usually occurs in otherwise healthy subjects after minor trauma. An ill-defined erythema, often on the head or limbs and associated with a high fever, rapidly becomes necrotic. Early surgical debridement and systemic antibiotics are essential.

Staphylococcal and streptococcal infections

Normal skin microflora includes staphylococci, micrococci, corynebacteria and propionibacteria, and may number 0.5 million/cm2. Some individuals are higher carriers than others.

Normal skin microflora includes staphylococci, micrococci, corynebacteria and propionibacteria, and may number 0.5 million/cm2. Some individuals are higher carriers than others.

Staphylococcal infection of the skin may be primary, e.g. impetigo, ecthyma or folliculitis, or secondary, e.g. superinfection of eczema, psoriasis or leg ulcers.

Staphylococcal infection of the skin may be primary, e.g. impetigo, ecthyma or folliculitis, or secondary, e.g. superinfection of eczema, psoriasis or leg ulcers.

Streptococcal infections may also be primary, e.g. erysipelas or cellulitis, or secondary, e.g. infection of dermatoses or leg ulcers.

Streptococcal infections may also be primary, e.g. erysipelas or cellulitis, or secondary, e.g. infection of dermatoses or leg ulcers.