Pigmentation

Skin colour is due to a mixture of the pigments melanin (p. 8), oxyhaemoglobin (in blood) and carotene (in the stratum corneum and subcutaneous fat). Pigmentary diseases are common and particularly distressing to those with darker skin. Disorders of pigmentation mainly involve melanocytes, but other causes are mentioned where relevant.

Hypopigmentation

Pigment loss may be generalized or patchy. Generalized hypopigmentation occurs with albinism, phenylketonuria and hypopituitarism; patchy loss is seen in vitiligo, after inflammation, following exposure to some chemicals and with certain infections (Table 1).

Table 1 Causes of hypopigmentation

| Cause | Example |

|---|---|

| Chemical | Substituted phenols, hydroquinone |

| Endocrine | Hypopituitarism |

| Genetic | Albinism, phenylketonuria, tuberous sclerosis, piebaldism |

| Infection | Leprosy, yaws, pityriasis versicolor |

| Postinflammatory | Cryotherapy, eczema, psoriasis, morphoea, pityriasis alba |

| Other | Vitiligo, lichen sclerosus, halo naevus, scarring |

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is an acquired idiopathic disorder showing white non-scaly macules. The association with thyroid disease, pernicious anaemia and Addison’s disease suggests an autoimmune aetiology in some cases. About 30% of patients give a family history of the disorder. Melanocytes are absent from affected skin on histology.

Clinical presentation

Vitiligo affects 0.5% of the population, is seen in all races and is most troublesome in those with a dark skin. The sex incidence is equal, and the onset, usually between 10 and 30 years of age, may be precipitated by injury or sunburn. The sharply defined white macules are often symmetrical (Fig. 1). The hands, wrists, knees, neck and areas around orifices (e.g. the mouth) are frequently affected. Occasionally, vitiligo is segmental (e.g. down an arm), generalized or universal. The course is unpredictable; areas may remain static, spread or (infrequently) repigment. In light-skinned individuals, vitiligo may be discernible only in summer, when the non-vitiliginous areas become sun-tanned.

Differential diagnosis

Postinflammatory hypopigmentation is often accompanied by other skin changes (Table 1). In chemical leucoderma, a history of exposure to phenolic chemicals should be sought. The hypopigmented macules of leprosy are normally anaesthetic.

Management

Treatment is unsatisfactory. Camouflage cosmetics require patience and skill to apply. Sunscreens help the lightly pigmented patient by reducing the tanning and contrast of the non-vitiligo areas. In patients with a darker skin, topical potent steroids or tacrolimus can induce some repigmentation. Ultraviolet (UV) B or psoralen with UVA (PUVA) may help, although it can take months and any repigmentation might subsequently be lost. Rarely, depigmentation using p(benzyloxy)phenol is considered when vitiligo is near universal and other treatments have failed.

Albinism

Albinism is an autosomal recessive condition in which the melanocytes fail to synthesize pigment in the epidermis, hair bulb and eye.

There are several syndromes of albinism. All are autosomal recessive and show a lack of pigment in the skin, hair, iris and retina. Melanocyte numbers are normal, but melanosome production fails due to defective gene control of tyrosinase (p. 8).

Albinism is uncommon (the prevalence is 1/20 000), although the diagnosis is straightforward. The skin is white or pink, the hair white and pigmentation is lacking in the eye (Fig. 2). Albinos have poor sight, photophobia and nystagmus. ‘Tyrosinase-positive’ albinos may pigment slightly with age, so that black African skin becomes yellow and freckled. In the tropics, albinos risk premature skin photoageing and the early onset of skin tumours, especially squamous cell carcinomas.

Strict sun avoidance from childhood is essential. Opaque clothing, a wide-brimmed hat and sunscreens are needed. Prenatal diagnosis is possible.

Phenylketonuria

Phenylketonuria is an autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism. Phenylalanine hydroxylase, which converts phenylalanine into tyrosine, is deficient. Phenylalanine and metabolites accumulate and damage the developing neonatal brain. The prevalence is 1/10 000 births.

Phenylketonuria is detected after birth by routine screening tests. Untreated, mental retardation and choreoathetosis develop. Patients have fair hair and skin, due to impaired melanin synthesis. Atopic eczema is common. A low phenylalanine diet, given early, prevents neurological damage.

Hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is mostly hypermelanosis (Table 2), but sometimes other pigments colour the skin, e.g. iron deposition (with melanin) in haemochromatosis, and carotene (causing an orange discoloration) in carotenaemia, usually due to eating too many carrots.

Table 2 Causes of hyperpigmentation

| Cause | Example |

|---|---|

| Drugs | Photosensitizers, psoralens, oestrogens, phenothiazines, minocycline, amiodarone |

| Endocrine | Addison’s disease, Cushing syndrome, Graves’ disease |

| Genetic | Racial, freckles, neurofibromatosis, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome |

| Metabolic | Biliary cirrhosis, haemochromatosis, porphyria |

| Nutritional | Carotenaemia, malabsorption, malnutrition, pellagra |

| Postinflammatory | Eczema, lichen planus, systemic sclerosis, lichen amyloidosis |

| Other | Acanthosis nigricans, naevi, malignant melanoma, argyria, chronic renal failure |

Freckles and lentigines

Freckles (ephelides) are small, light-brown macules, typically facial, which darken on sun exposure. Lentigines are also brown macules but are scattered and do not darken in the sun. Freckles have normal basal layer melanocyte numbers but increased melanin. Lentigines have an increased number of melanocytes.

Freckles are common, especially in red-haired children. Lentigines may develop in childhood but are more common in sun-exposed elderly skin. Freckles require no treatment. Lentigines respond to cryotherapy.

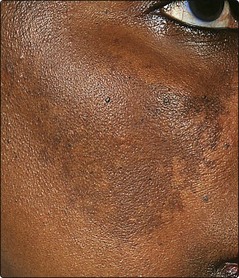

Melasma (chloasma)

Melasma is a patterned macular facial pigmentation occurring with pregnancy and in women on oral contraceptives. The pigmentation is symmetrical and often involves the forehead (Fig. 3). Pregnancy stimulates melanocytes generally, and also increases pigmentation of the nipples and lower abdomen and in existing melanocytic naevi. Melasma may improve spontaneously. Topical tretinoin, azelaic acid or hydroquinone can reduce pigmentation. Sunscreens and camouflage cosmetics can help.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant condition. Lentigines around the lips (Fig. 4), buccal mucosa and fingers are associated with small bowel polyps. The polyps may cause intussusception and rarely undergo malignant change.

Addison’s disease

Addison’s disease is characterized by hypoadrenalism with pituitary overproduction of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). The skin signs are due to excess ACTH, which stimulates melanogenesis. Pigmentation may be generalized or limited to the buccal mucosa (Fig. 5), palmar creases, scars, flexures or areas subjected to friction. Addisonian-like pigmentation is also seen in Cushing syndrome, hyperthyroidism and acromegaly.

Drug-induced pigmentation

Drug-induced pigmentation may be due to stimulation of melanogenesis or deposition of the drug in the skin, but the mechanism is often not well understood (Table 3, p. 86). Of the commonly used drugs, amiodarone, phenothiazines and minocycline not infrequently induce pigmentation.

Table 3 Drug-induced pigmentation

| Drug | Effect |

|---|---|

| Amiodarone | Blue-grey pigmentation of exposed areas (p. 87) |

| Bleomycin | Diffuse pigmentation, often flexural; flagellate pattern |

| Busulfan | Diffuse brown pigment |

| Chloroquine | Blue-grey pigmentation of face and arms |

| Chlorpromazine | Slatey-grey pigment in sun-exposed sites |

| Clofazimine | Red and black pigment |

| Mepacrine | Yellow (drug deposited) |

| Minocycline | Blue-black pigment in scars and sun-exposed sites |

| Psoralens | Topical or systemic photosensitizers (cosmetics) |

Disorders of pigmentation

Vitiligo: common, autoimmune; well-defined depigmented macules.

Vitiligo: common, autoimmune; well-defined depigmented macules.

Albinism: rare, autosomal recessive; lack of skin and eye pigment; need strict sun avoidance; risk of skin cancer.

Albinism: rare, autosomal recessive; lack of skin and eye pigment; need strict sun avoidance; risk of skin cancer.

Phenylketonuria: autosomal recessive enzyme defect; fair skin and hair.

Phenylketonuria: autosomal recessive enzyme defect; fair skin and hair.

Freckles: brown macules darken with sun; normal number of melanocytes.

Freckles: brown macules darken with sun; normal number of melanocytes.

Lentigines: brown macules; melanocyte numbers are increased.

Lentigines: brown macules; melanocyte numbers are increased.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome: autosomal dominant disorder of perioral lentigines and intestinal polyps.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome: autosomal dominant disorder of perioral lentigines and intestinal polyps.

Melasma: facial pigmentation; related to pregnancy and ‘the pill’.

Melasma: facial pigmentation; related to pregnancy and ‘the pill’.

Addison’s disease: ACTH-stimulated melanogenesis of mucosae and flexures.

Addison’s disease: ACTH-stimulated melanogenesis of mucosae and flexures.

Drug-induced pigmentation: due to deposition of pigment or stimulation of melanogenesis.

Drug-induced pigmentation: due to deposition of pigment or stimulation of melanogenesis.