Blistering disorders

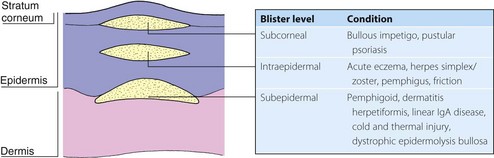

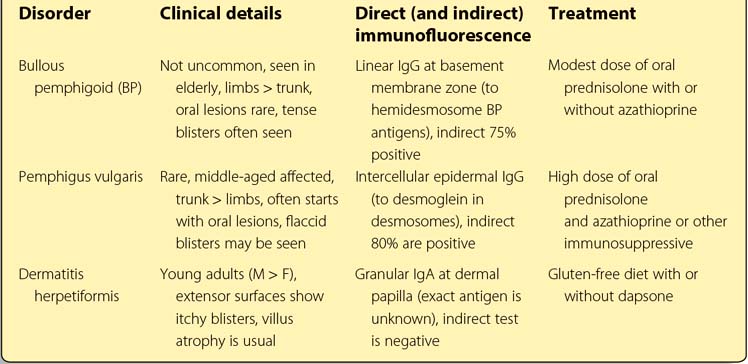

Blistering is often seen with skin disease. It is found with common dermatoses such as acute contact dermatitis, pompholyx, herpes simplex, herpes zoster and bullous impetigo, and it also occurs after insect bites, burns and friction or cold injury. The type of blister depends on the level of cleavage: subcorneal or intraepidermal blisters rupture easily, but subepidermal ones are not so fragile (Fig. 1). The primary acquired autoimmune bullous disorders, dealt with here, are rare but important.

Pemphigus

Pemphigus is an uncommon, severe and potentially fatal autoimmune blistering disorder affecting the skin and mucous membranes.

Aetiopathogenesis

Over 80% of patients have circulating immunoglobulin (Ig) G autoantibodies detectable in the serum by indirect immunofluorescence (p. 127), which bind with desmoglein, a desmosomal cadherin involved in epidermal intercellular adhesion. The antibodies, possibly with complement activation and protease release, result in loss of adhesion and an intraepidermal split. Direct immunofluorescence shows the intercellular deposition of IgG in the suprabasal epidermis. Pemphigus is associated with other organ-specific autoimmune disorders such as myasthenia gravis.

Clinical presentation

In Europe, pemphigus is much less common than pemphigoid, and tends to affect middle-aged or young adults. Oral erosions signal the onset of pemphigus vulgaris in 50–70% of patients and often precede cutaneous blistering by months. Flaccid superficial blisters develop over the scalp, face, back, chest and flexures. The blistering is not always obvious, and lesions may consist of crusted erosions. Untreated, the blistering is progressive and, prior to the introduction of steroids, three out of four patients died within 4 years, usually from uncontrolled fluid and protein loss or secondary infection.

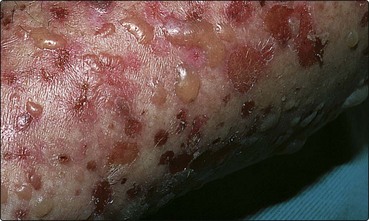

Less common variants include pemphigus foliaceus, in which shallow erosions appear on the scalp, face and chest (Fig. 2), and pemphigus vegetans, in which pustular and vegetating lesions affect the axillae and groins. In Brazil, an endemic form of pemphigus foliaceus, fogo selvagem, seems to be induced by an infective agent. Paraneoplastic pemphigus describes a variant associated with underlying malignancy.

Differential diagnosis

Aphthous ulcers or Behçet’s disease can simulate the oral erosions of pemphigus. Cases with rapid onset need to be differentiated from toxic epidermal necrolysis. Widespread skin erosions may suggest epidermolysis bullosa or pemphigoid. The diagnosis relies on the histological examination of a bulla and direct immunofluorescence.

Management

Systemic steroids and other immunosuppressive agents are required. Prednisolone is given initially in a high dose (1.0–1.5 mg/kg daily), often with azathioprine or cyclophosphamide. Once blistering is controlled, the steroid dosage can be lowered. Treatment usually needs to be continued for years, although remission occurs occasionally. Mortality and morbidity are now more likely to be due to side-effects of the steroid and immunosuppressive therapy than to the disease itself. Recent reports have shown depletion of B cells with rituximab (anti-CD20) monoclonal antibody therapy to be useful in this condition.

Pemphigoid

Pemphigoid is a chronic and not uncommon blistering eruption of the elderly.

Aetiopathogenesis

IgG autoantibodies to bullous pemphigoid antigens BP230 and BP180 in the hemidesmosomes at the basement membrane zone bind complement, which induces inflammation and protease release, leading to subepidermal bulla formation. The IgG and C3 are detected by direct immunofluorescence (p. 127). Indirect methods demonstrate circulating autoantibodies in 75% of cases.

Clinical presentation

Bullous pemphigoid usually affects the elderly. Tense large blisters arise on red or normal-looking skin, often of the limbs, trunk and flexures (Fig. 3). Oral lesions occur in only 10% of cases. A pruritic urticarial eruption may precede the onset of blistering. Pemphigoid is sometimes localized to one site, often the lower leg. The differential diagnosis of pemphigoid may include dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease or pemphigus. Immunofluorescence and histology reveal the diagnosis.

Cicatricial pemphigoid mainly affects the ocular and oral mucous membranes. Scarring results, and this can cause serious eye problems. Pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis is a rare but characteristic, intensely itchy bullous eruption associated with pregnancy, which remits after the delivery but can recur during subsequent pregnancies.

Management

Pemphigoid responds to a lower dose of steroids than pemphigus: 0.5 mg/kg daily of oral prednisolone is usually sufficient, and this can normally be reduced to below 15 mg within weeks. Azathioprine is sometimes also prescribed. The disease is self-limiting in many cases, and steroids can often be stopped after 2–3 years. Cicatricial pemphigoid does not respond so well, but pemphigoid gestationis is controlled by standard doses. Steroid-induced side-effects may be a problem, especially in the elderly.

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an uncommon eruption of symmetrical itchy blisters on the extensor surfaces. Jejunal villus atrophy is an associated finding in most cases.

Aetiopathogenesis

DH is characterized by the finding of granular IgA at the dermal papillae on immunofluorescence, and by the response of the skin lesions (and the villus atrophy seen in over 75% of patients) to a gluten-free diet. Despite this, the cause of the eruption – and its relationship to the undoubted gluten sensitivity of both the gut and the skin – remains unclear. It is doubtful whether the IgA induces the itch, as it is present in asymptomatic patients.

Clinical presentation

DH usually presents in the third or fourth decade and is twice as common in males as in females. The classical onset is with groups of small, intensely itchy vesicles on the elbows, knees, buttocks and scalp (Fig. 4). The blisters are often broken by scratching to leave excoriations. Although most patients have small bowel villus atrophy, symptoms of gastrointestinal disturbance and malabsorption are uncommon.

Differential diagnosis

Distinction from scabies, eczema and linear IgA disease is important. Biopsy shows a subepidermal bulla, and direct immunofluorescence of normal-looking skin demonstrates granular IgA at the dermal papilla (p. 127). The small bowel can be investigated by jejunal biopsy. Serum folate, vitamin B12 and ferritin estimates detect any biochemical malabsorption. Antiendomysial antibodies are present.

Management

A gluten-free diet is the treatment of choice, as this corrects both the bowel and the skin lesions. Dapsone (50–200 mg daily) will control the eruption and is often given until the gluten-free diet has its beneficial effect. A haemolytic anaemia may occur with dapsone. Regular blood counts are necessary.

Linear IgA disease

Linear IgA disease is a rare heterogeneous condition of blisters and urticarial lesions on the back or extensor surfaces (Fig. 5). The disorder responds to dapsone and may resemble DH or pemphigoid. Direct immunofluorescence reveals linear IgA at the basement membrane. In the childhood variant, blisters occur around the genitalia. Linear IgA disease induced by medication (commonly vancomycin) is well recognized.