CHAPTER 19 Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

DIAGNOSIS DEFINED

A diagnosis is an identification of a condition, problem, or situation based on the analysis of its cause and defining characteristics. The diagnostic process is generic but can be applied to specific disciplines; a diagnosis becomes discipline-specific when it is applied to the practice of that discipline. The dental hygienist diagnoses client conditions within the scope of dental hygiene to prevent oral disease, minimize the risk of oral disease, and promote wellness.

Miller introduced the concept of the dental hygiene diagnosis to describe the expression of dental hygiene judgment and decision making.1 The dental hygiene profession has accepted diagnosis as part of the dental hygienist's role. The American Dental Education Association's Competencies for Entry into Dental Hygiene, the American Dental Hygienists' Association's Code of Ethics and Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice, and the Commission on Dental Accreditation's Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs all use the term dental hygiene diagnosis.2-4

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

A dental hygiene diagnosis is a clinical decision made by a dental hygienist that identifies an actual or potential human need deficit that the dental hygienist is educated and licensed to treat (meet) and/or to refer for care. A dental hygiene diagnosis has the following characteristics:

Is necessary for planning and implementing effective dental hygiene care and evaluating its outcomes

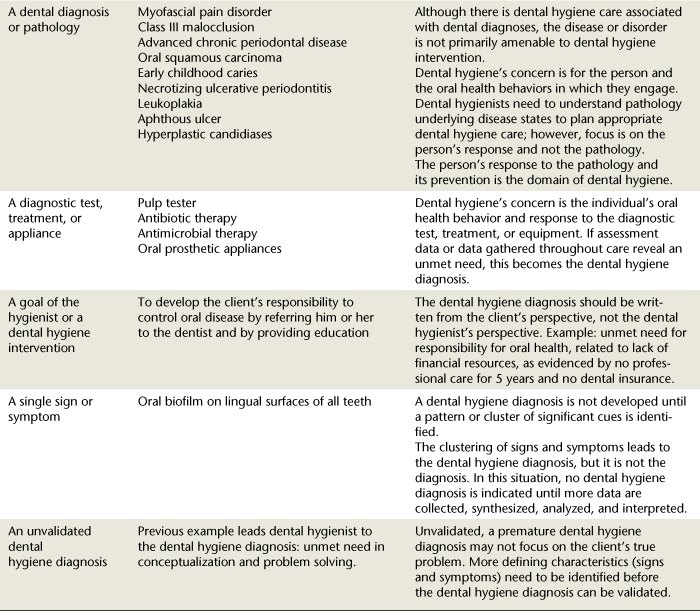

Is necessary for planning and implementing effective dental hygiene care and evaluating its outcomesTherefore after the assessment phase of the dental hygiene process the diagnostic process begins (Figure 19-1). Making a dental hygiene diagnosis includes identifying the following

Figure 19-1 The concept of diagnosis within the dental hygiene process. The term dental hygiene diagnosis is used to describe actual or potential oral health problems that can be prevented or resolved by dental hygiene interventions. Broken line indicates completion of care until next continued care visit.

In making a dental hygiene diagnosis the dental hygienist works within the scope of dental hygiene practice. The process requires a concrete understanding of the scope of dental hygiene and collaboration between the dental hygienist and dentist.5

Historically, dental hygienists were cautioned to not diagnose, but to identify dental problems and then communicate the observations using phrases such as the following

Such observations are neither dental nor dental hygiene diagnoses and create confusion for the client. If state law permits preliminary diagnostic services provided by the dental hygienist, the dental hygienist could say the following

“Mr. Jones, my preliminary diagnosis suggests dental caries on several of your teeth; the final dental diagnosis must be made by the dentist.”

“Mr. Jones, my preliminary diagnosis suggests dental caries on several of your teeth; the final dental diagnosis must be made by the dentist.” “Ms. Smith, the periodontal probing depths of 5 to 7 mm, mobility of 2, and bleeding around the lower front suggest moderate periodontitis; however, the final diagnosis must be confirmed by the dentist.”

“Ms. Smith, the periodontal probing depths of 5 to 7 mm, mobility of 2, and bleeding around the lower front suggest moderate periodontitis; however, the final diagnosis must be confirmed by the dentist.” “Mrs. Carson, your son has a radiolucent area on the root tip of his top front tooth suggesting a pathologic condition; however, a dental diagnosis must be made by the dentist.”

“Mrs. Carson, your son has a radiolucent area on the root tip of his top front tooth suggesting a pathologic condition; however, a dental diagnosis must be made by the dentist.”When a dental hygienist identifies oral disease, such as gingivitis or early periodontitis, this is called a preliminary diagnosis, which must be referred to a dentist for a definitive diagnosis and treatment or for possible delegation by the dentist back to the dental hygienist for nonsurgical periodontal care. When the client displays signs and symptoms of oral conditions that require diagnosis and treatment by a dentist, a dental consultation and referral are indicated for high-quality client care. When a client displays signs and symptoms of systemic conditions that require medical diagnosis and treatment by a physician, a medical consultation and referral are indicated.

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis versus Dental Diagnosis

Legal, professional, and social responsibilities require clear distinctions between a dental hygiene diagnosis and a dental diagnosis. Diagnostic decision making and therapeutic care fall within precise legal and professional boundaries. Dental diagnoses identify diseases or conditions for which the dentist directs or provides the primary treatment; dental hygiene diagnoses identify unmet human needs (also known as human need deficits) that can be met by dental hygienists within the scope of dental hygiene practice. Both types of diagnoses serve different purposes as related to the professional's scope of practice (Table 19-1).

TABLE 19-1 Dental Hygiene Diagnosis versus Dental Diagnosis

| Dental Hygiene Diagnosis | Dental Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Identifies an unmet human need (human need deficit) | Identifies a specific oral disease |

| Identifies conditions or problems (unmet human needs) within the scope of dental hygiene practice | Identifies conditions or problems for which the dentist directs the primary treatment |

| Often deals with the client's perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and motivations regarding his or her own oral status | Often deals with the actual pathophysiologic changes |

| May change as the client's responses and behaviors change | Remains the same for as long as the disease is present |

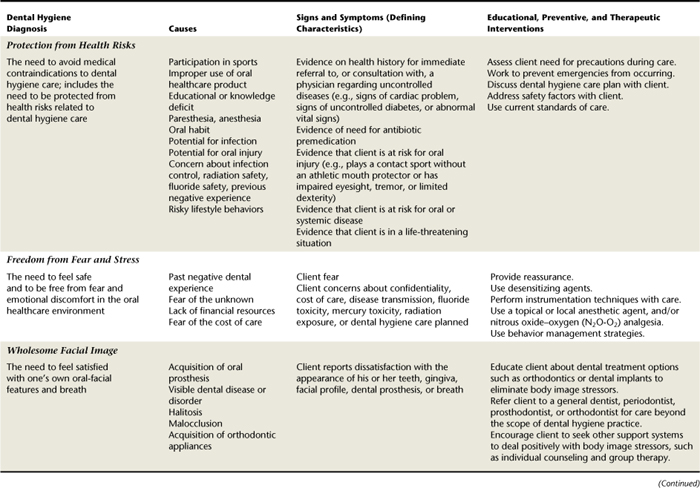

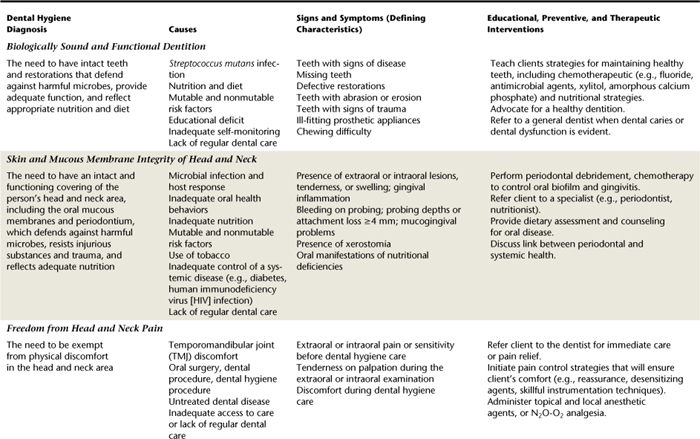

Dental Hygiene Diagnostic Classifications6

Making a dental hygiene diagnosis that is recognized as separate from a dental diagnosis requires a unique system to classify relevant clinical data about the client. Currently a classification of eight possible diagnoses (i.e., eight human needs) creates a standardized language for identifying client oral health conditions amenable to dental hygiene care. The dental hygiene diagnostic classification uses descriptors that focus on the client's human needs, thus emphasizing the client as an integrated human being rather than as a disease entity. This classification, based on eight human needs, is designed to work synergistically with the diagnosis of the dentist and other healthcare professionals. The diagnostic classification allows dental hygienists to focus on client needs and to communicate this information to both the client and other health professionals (Table 19-2).

DENTAL HYGIENE DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

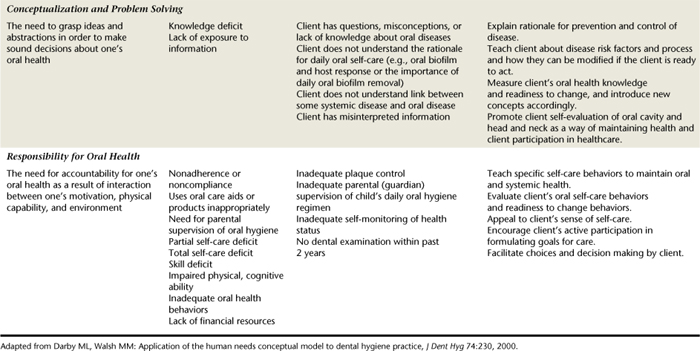

The diagnostic process, a problem-solving approach to clinical decision making, guides the intellectual activity of the dental hygienist (Figure 19-2). The dental hygiene diagnostic process uses eight human needs related to dental hygiene care as its foundation (see Table 19-2). Dental hygiene diagnoses focus on professional care and allow dental hygienists to assess and manage client conditions within their scope of practice. After diagnosis, goals are developed in conjunction with the client. Client goals—the desired outcome of care—clarify what the client needs to do to promote, maintain, or achieve oral health and wellness. Planning care is contingent on the dental hygiene diagnosis (see Chapter 20).

Synthesis, Analysis, and Interpretation of Assessment Data

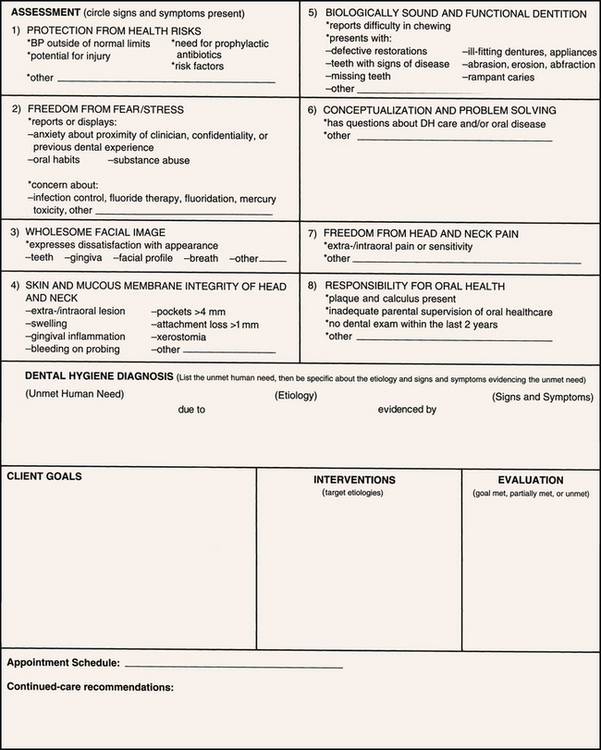

Dental hygienists begin data synthesis, analysis, and interpretation during assessment. Figure 19-3 provides a tool that can be used to assess the client's unmet human needs. The dental hygienist looks for significant clusters of data that signal the presence of an actual or potential unmet human need, formulates a diagnosis, and develops a care plan (see Chapter 20).

Using Standards to Validate Diagnoses

To arrive at a valid dental hygiene diagnosis, the dental hygienist can compare observed data (objective and subjective) with an accepted standard. Appropriate standards include normative values for the client's age and oral status. For example, a child's gingival architecture may be normal given the child's developmental level but may be considered abnormal at another age. Similarly, a blood pressure of 130/90 mm Hg might be within the expected range for an individual with hypertension under the control of a physician but abnormal for a person not under a physician's care. To recognize significant data, consider the following

Recognizing Patterns

Dental hygiene diagnoses should always be based on a cluster of significant information rather than on a single sign or symptom. The danger of arriving at a dental hygiene diagnosis from a single factor is evident from this example: The dental hygienist diagnoses an Eastern Indian woman as having an unmet human need for a wholesome facial image. The diagnosis looks to be related to a lack of dental care as evidenced by malpositioned teeth and a prognathic profile, but the observed data may have been misinterpreted. The dental hygienist mistakenly identified the cause as lack of dental care when really it is rooted in the client's culture, which accepts malocclusion as within the range of normal. The woman has had regular dental care throughout her life, but no orthodontic care because of her cultural orientation. Gathering complete data to support a recognizable pattern prevents the dental hygienist from formulating an incorrect diagnosis.

Identifying Unmet Human Needs

The next step in the diagnostic process is to determine the client's unmet human needs. The dental hygienist distinguishes between oral health conditions that only a dentist is qualified to treat (dental diagnosis), which requires a dental referral, and oral health conditions that require dental hygiene care (dental hygiene diagnosis). Here, critical thinking determines whether the identified condition requires a dental diagnosis, a dental hygiene diagnosis, or a medical diagnosis.

The client may also present information during the assessment indicating that he or she is at risk for developing an unmet human need (i.e., an at-risk problem). For example, the dental hygienist records that a client has signs of possible uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, but a hemoglobin A1c test has not been done for at least 6 months. The dental hygienist then predicts problems this client is likely to experience as a result: a diabetic emergency, longer healing period than normal, continued breakdown of collagen and alveolar bone, and elevated risk for infection. These potential problems are related to the diagnosis of unmet human needs for protection from health risks and for skin and mucous membrane integrity.

Dental hygiene diagnoses have implications for planning interventions. For example, interventions may include collaboration with and referral to the dentist and physician of record, analysis of the client's diet and nutrition, review of the client's medication schedule, reduction in length of appointment, prophylactic antibiotic premedication, use of antibacterial dentifrices and mouth rinses to control the bacterial load, and establishment of a personal oral self-care program.

Identifying Strengths (Protective Factors)

At times a client may present no unmet human needs. This situation is an opportunity for the dental hygienist to identify the client's protective factors, build on these strengths for greater levels of oral wellness, and reinforce oral health promotion interventions to maintain and augment wellness. Protective factors may include maintaining good systemic health, living a healthy lifestyle, not smoking, eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables and low in animal fats, exercising regularly, valuing personal health, seeking regular professional medical and oral care, and meticulously performing daily oral self-care behaviors.

FORMULATING AND VALIDATING DENTAL HYGIENE DIAGNOSES

Writing Dental Hygiene Diagnostic Statements

After analyzing the client's data, the dental hygienist reaches one of four conclusions, all of which require different actions. These conclusions and actions are shown in Table 19-3.

TABLE 19-3 Possible Conclusions and Actions Taken by the Dental Hygienist after Analyzing Client Assessment Data

| Conclusion | Dental Hygiene Actions |

|---|---|

| No unmet human needs related to dental hygiene care | Initiate oral health promotion strategies to achieve higher levels of oral and systemic wellness.Reinforce client's oral health beliefs and behaviors. |

| Possible unmet human needs related to an oral health problem | Collect more assessment data to validate suspected problem, which may require a dental hygiene diagnosis, a dental diagnosis, or a medical diagnosis. |

| Actual or potential unmet human needs related to dental hygiene care (dental hygiene diagnosis) | Plan, implement, and evaluate dental hygiene care. |

| Actual or potential unmet human needs requiring a diagnosis by another healthcare professional | Consult with and refer to appropriate healthcare professional; work collaboratively to solve problem. |

If the action requires a diagnosis, the dental hygienist formulates, validates, and prioritizes dental hygiene diagnoses before care. Formulation of the dental hygiene diagnosis is based on the identification of the client's human needs as supported by the assessment data. More than one unmet human need may be found, and multiple dental hygiene diagnoses may be identified.

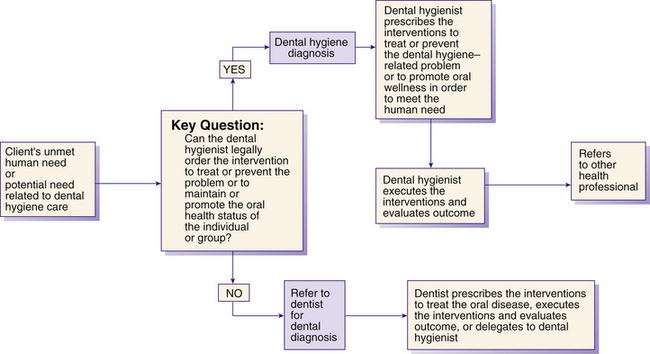

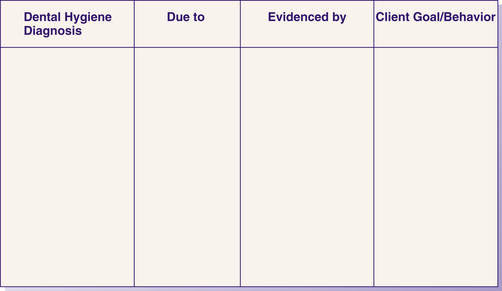

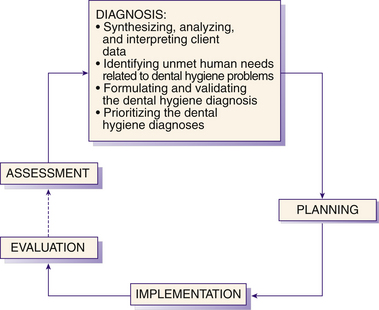

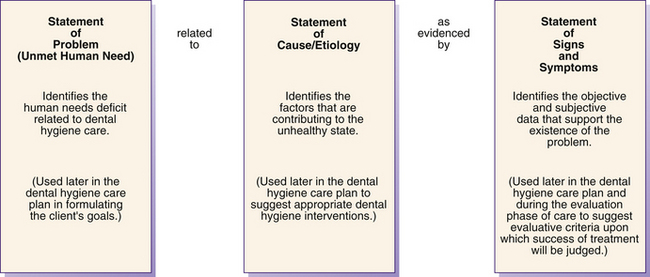

Three components comprise a diagnostic statement (Figure 19-4)

Unmet human need: Oral health condition or potential (at-risk) health problem amenable to dental hygiene intervention

Unmet human need: Oral health condition or potential (at-risk) health problem amenable to dental hygiene intervention

Figure 19-4 Three parts of a dental hygiene diagnostic statement.

(Adapted from Darby ML, Walsh MM: Application of the human needs conceptual model to dental hygiene practice, J Dent Hyg 74:230, 2000.)

A diagnostic statement links the client's problem and its cause, guides the selection of interventions, and facilitates the definition of expected outcomes to evaluate the efficacy of care (see Chapter 20 for a discussion of expected outcomes).

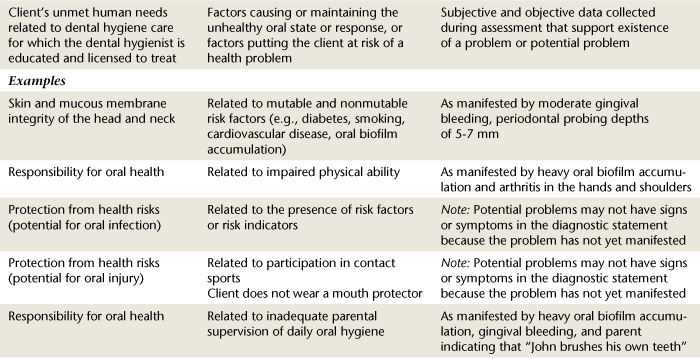

Table 19-4 presents examples of dental hygiene diagnostic statements. Eight diagnostic categories (i.e., eight human needs) presented in Table 19-2 outline possible dental hygiene diagnoses. In this approach to diagnosing, the organizing principle guiding the diagnosis is human needs theory. The diagnostic statement provides a focus on specific client unmet needs so that the routine approach, characteristic of traditional dental hygiene care (a 45-minute appointment for oral prophylaxis, bitewing radiographs, fluoride application, and 6-month continued care) is no longer an appropriate standard.

TABLE 19-4 Formulation of Dental Hygiene Diagnostic Statements

| Dental Hygiene Diagnosis | Cause | Signs and Symptoms/Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Definitions | ||

| Client's unmet human needs related to dental hygiene care for which the dental hygienist is educated and licensed to treat | Factors causing or maintaining the unhealthy oral state or response, or factors putting the client at risk of a health problem | Subjective and objective data collected during assessment that support existence of a problem or potential problem |

| Examples | ||

| Skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck | Related to mutable and nonmutable risk factors (e.g., diabetes, smoking, cardiovascular disease, oral biofilm accumulation) | As manifested by moderate gingival bleeding, periodontal probing depths of 5-7 mm |

| Responsibility for oral health | Related to impaired physical ability | As manifested by heavy oral biofilm accumulation and arthritis in the hands and shoulders |

| Protection from health risks (potential for oral infection) | Related to the presence of risk factors or risk indicators | Note: Potential problems may not have signs or symptoms in the diagnostic statement because the problem has not yet manifested |

| Protection from health risks (potential for oral injury) | Related to participation in contact sportsClient does not wear a mouth protector | Note: Potential problems may not have signs or symptoms in the diagnostic statement because the problem has not yet manifested |

| Responsibility for oral health | Related to inadequate parental supervision of daily oral hygiene | As manifested by heavy oral biofilm accumulation, gingival bleeding, and parent indicating that “John brushes his own teeth” |

| Wholesome facial image | Related to a Class II, division I malocclusion | As manifested by client's malocclusion and consistent derogatory remarks about her teeth |

Each diagnosis has a cluster of defining characteristics that must be observed during client assessment. The defining characteristics are the signs and symptoms that must be evident for the diagnostic label to be used correctly (see Table 19-2). The signs and symptoms are predictors for judging the presence of an unmet human need related to an oral health condition or a potential problem. The client's signs and symptoms enable the dental hygienist to focus on the true problem and to eliminate others. (The result of this process is referred to as the differential diagnosis.)

Sometimes the client may not have a problem yet but has risk factors and risk indicators suggesting that he or she is at risk for a problem. At-risk problems are conditions that should also be diagnosed so that actions can be taken to prevent the potential problem from developing. If the client is at risk for an oral health problem, there may not be signs and symptoms because the problem has not yet occurred; however, it is still preventable if risk factors are modified.

A diagnosis should be accompanied by noting

The objective signs observed by the dental hygienist and the subjective symptoms reported by the client (defining characteristics as evidence of the problem)

The objective signs observed by the dental hygienist and the subjective symptoms reported by the client (defining characteristics as evidence of the problem)Thus a dental hygiene diagnosis is written as a three-part diagnostic statement:

Dental hygiene diagnoses should be documented as a permanent entry on the client's record. Guidelines for writing dental hygiene diagnoses are in Box 19-1. An example of a diagnostic statement is an unmet human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck, related to skill deficiency in removing oral biofilm, as evidenced by plaque and gingival bleeding scores of 5 and 3, respectively.

BOX 19-1 Guidelines for Writing Dental Hygiene Diagnoses

Potential health problems may not require specification of the cause. In these situations the observed risk factors are the defining characteristics. A dental hygiene diagnosis regarding an at-risk problem is written with its presenting risk factors as the defining characteristics. For example, a potential unmet need for freedom from health risks, as manifested by the daily use of spit tobacco.

Errors in Writing a Dental Hygiene Diagnostic Statement

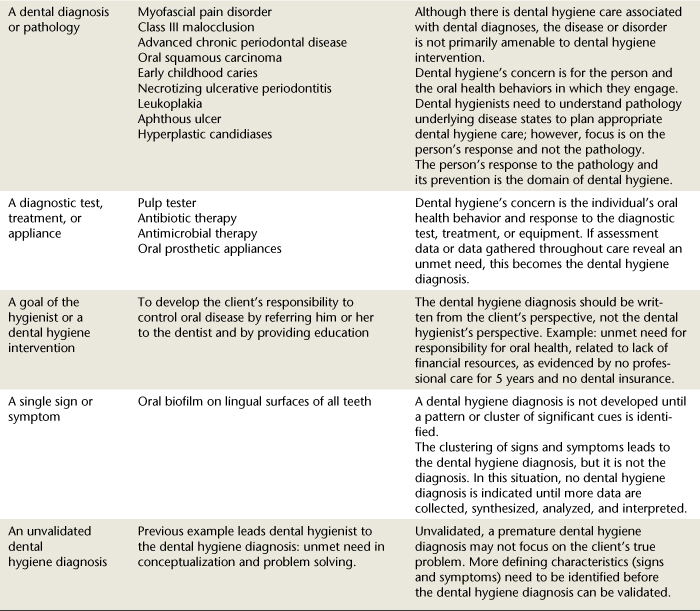

The most frequent errors found in dental hygiene diagnostic statements include using emotional terms, including a dental diagnosis, including a medical diagnosis, presenting the cause as the diagnosis, or presenting signs and symptoms as the diagnosis rather than phrasing the diagnosis in terms of the client's unmet needs. These common errors are listed in Table 19-5, with guidelines on how these errors can be corrected. The dental hygienist must also avoid personal beliefs and values in the diagnostic statement by always referring to the documented data as assessed and/or reported by the client and recorded in the dental chart. Nothing should be recorded that insinuates negligence in the treatment rendered by another practitioner. For example, an unmet need for a biologically sound dentition, due to poor dentistry, as manifested by overhanging restorations. Table 19-6 provides examples of conditions that are not dental hygiene diagnoses.

TABLE 19-6 What a Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Is Not

| It Is Not… | Examples | Rationales |

|---|---|---|

| A dental diagnosis or pathology | ||

| A diagnostic test, treatment, or appliance | Dental hygiene's concern is the individual's oral health behavior and response to the diagnostic test, treatment, or equipment. If assessment data or data gathered throughout care reveal an unmet need, this becomes the dental hygiene diagnosis. | |

| A goal of the hygienist or a dental hygiene intervention | To develop the client's responsibility to control oral disease by referring him or her to the dentist and by providing education | The dental hygiene diagnosis should be written from the client's perspective, not the dental hygienist's perspective. Example: unmet need for responsibility for oral health, related to lack of financial resources, as evidenced by no professional care for 5 years and no dental insurance. |

| A single sign or symptom | Oral biofilm on lingual surfaces of all teeth | A dental hygiene diagnosis is not developed until a pattern or cluster of significant cues is identified. The clustering of signs and symptoms leads to the dental hygiene diagnosis, but it is not the diagnosis. In this situation, no dental hygiene diagnosis is indicated until more data are collected, synthesized, analyzed, and interpreted. |

| An unvalidated dental hygiene diagnosis | Previous example leads dental hygienist to the dental hygiene diagnosis: unmet need in conceptualization and problem solving. | Unvalidated, a premature dental hygiene diagnosis may not focus on the client's true problem. More defining characteristics (signs and symptoms) need to be identified before the dental hygiene diagnosis can be validated. |

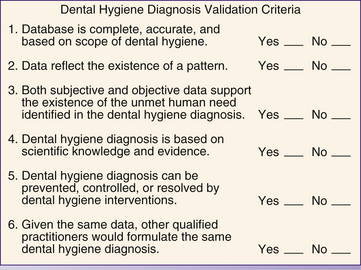

Validation of the Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

Once the diagnosis is formulated, it must be validated. An affirmative response to each of the statements in Figure 19-5 validates the dental hygiene diagnosis7 (see Chapter 20). The format in Figure 19-6 can be used to practice the process of diagnostic decision making. The dental hygienist can begin by reviewing Scenarios 19-1 to 19-3, in which the dental hygiene diagnostic process is applied clinically.

SCENARIO 19-1 YOUNG WOMAN WHO RECENTLY OBTAINED ORTHODONTIC APPLIANCES

SCENARIO 19-1 YOUNG WOMAN WHO RECENTLY OBTAINED ORTHODONTIC APPLIANCES

Brenda Smith, age 16, Asian American, and a junior in high school, received full orthodontic appliances 1 month ago. Although she wanted the orthodontic appliances to correct the severe crowding of her anterior teeth, she is now experiencing an adjustment problem. Although she was last treated for gingivitis before placement of the orthodontic appliances, she decides to visit her dental office for a 3-month checkup. On assessment, the dental hygienist finds Ms. Smith to have significant loss of weight, slight generalized plaque-induced gingivitis, and fair oral biofilm control. All other findings are within normal limits. Ms. Smith verbalizes that not very many 16-year-olds at her school wear braces, that she can't wait to get them off, and that she can't stand to look at herself in the mirror. One of her high school friends said that she looked weird. She obviously has been experiencing high anxiety since the orthodontic appliances were placed. She said that she has a difficult time eating because food sticks to the appliances, and she feels embarrassed if the appliances are retaining food. She no longer likes to eat with her friends in the school cafeteria or when she is out on weekends.

SCENARIO 19-2 CHILD WITH AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS

SCENARIO 19-2 CHILD WITH AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS

Devan Prince, age 12, female African American, is a new client in the dental practice and has been scheduled for dental hygiene care. Devan is in the seventh grade and is one of the star players on the girls' soccer team. She is with her mother Margaret (age 32) and her sister Bridget (age 10). After completing health and dental histories, the dental hygienist initiates a baseline assessment of the head and neck, intraoral and extraoral examination, a complete dental and periodontal assessment, assessment of human needs related to dental hygiene care, and client education and skill level assessment. Significant findings include 6-mm probing depths around teeth 19 and 30 and a 4- to 5-mm loss of clinical attachment around teeth 22 to 27. Oral hygiene is generally poor, and tooth mobility of periodontally involved teeth ranges from 2 to 3. Client has a knowledge deficit regarding oral biofilm, periodontal disease process, and status of the oral cavity.

SCENARIO 19-3 YOUNG CHILD WITH EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES

SCENARIO 19-3 YOUNG CHILD WITH EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES

Blake Olds, age 4, Caucasian, is brought to the dental hygiene care facility by his mother Caren, age 28. Caren is unemployed and on public assistance; therefore finances are a major concern. Blake has been in pain associated with his teeth. His mother reported that “he has been crying on and off for about 4 days, saying that his mouth hurt.” She indicates that she tries to appease his discomfort with sweets to eat. The dental hygienist conducts a complete health, dental, pharmacologic, and cultural history and initiates the assessment phase of the dental hygiene process. Given the immediate need for relieving the child's pain, she collaborates with the attending dentist, who extracts J, K, and L at that visit and who prescribes an antibiotic to control the infection. Blake's significant findings includes early childhood caries and periapical abscesses on J, K, and L, with caries also on teeth A, B, E, F, I, M, O, P, S, and T. After oral surgery the client is given postoperative instructions and is dismissed, and the dental hygienist analyzes the findings. Because of extraction and interproximal caries, the maintenance of space for the permanent teeth is a major concern. Although no significant periodontal probe depths were found, green and orange extrinsic stain, heavy materia alba, and oral biofilm were present throughout the mouth.

OUTCOMES OF DENTAL HYGIENE DIAGNOSES

Dental hygiene diagnoses facilitate the development of professional autonomy and accountability by focusing on phenomena within the scope of dental hygiene practice and by providing a language for communication. By identifying the client's unmet human needs that can be fulfilled through dental hygiene care, the dental hygiene diagnosis clarifies the role of the dental hygienist and allows for a defined scope and domain of dental hygiene practice. “Diagnosis by dental hygienists is not, and should not be, an attempt to move into the domain of the dentist; it is a vehicle for distinguishing roles professionally and legally.”1

Dental hygiene diagnosis facilitates the delivery of high- quality dental hygiene care and provides a criterion for establishing professional fees. Because dental hygiene diagnoses are based on a diagnostic classification system, communication among oral health professionals is facilitated. Diagnosis facilitates the measurement of clinical outcomes, which has implications for professional accountability, client education, research, regulatory mechanisms, direct access to care, and direct reimbursement. Use of dental hygiene diagnoses appears promising for the development of a computerized system of dental hygiene diagnosis and care planning, with expansion to a system of cost accounting for dental hygiene. The dental hygienist can review expected outcomes and dental hygiene interventions in Scenarios 19-1 to 19-3 as focused by the dental hygiene diagnoses.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Dental hygiene diagnoses reflect the scope of dental hygiene practice and never the scope of the dentist's practice. Avoid terminology in the diagnostic statement that implies blame or negligence, which could lead to litigation.

Dental hygiene diagnoses reflect the scope of dental hygiene practice and never the scope of the dentist's practice. Avoid terminology in the diagnostic statement that implies blame or negligence, which could lead to litigation. When client manifests signs and symptoms of oral conditions that require dental treatment by a dentist, a dental referral is indicated for high-quality care and legal protection. When client manifests signs and symptoms of systemic conditions that require medical evaluation and treatment, a medical consultation and referral are indicated for high-quality care and legal protection.

When client manifests signs and symptoms of oral conditions that require dental treatment by a dentist, a dental referral is indicated for high-quality care and legal protection. When client manifests signs and symptoms of systemic conditions that require medical evaluation and treatment, a medical consultation and referral are indicated for high-quality care and legal protection.KEY CONCEPTS

A dental hygiene diagnosis states the client's actual or potential (at-risk) problem related to oral health and disease.

A dental hygiene diagnosis states the client's actual or potential (at-risk) problem related to oral health and disease. Current standards (e.g., American Dental Education Association's Competencies for Entry into Dental Hygiene, the American Dental Hygienists' Association's Code of Ethics and Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice, the American Dental Association Commission on Dental Accreditation's Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs) expect dental hygienists to make dental hygiene diagnoses.

Current standards (e.g., American Dental Education Association's Competencies for Entry into Dental Hygiene, the American Dental Hygienists' Association's Code of Ethics and Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice, the American Dental Association Commission on Dental Accreditation's Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs) expect dental hygienists to make dental hygiene diagnoses. The diagnostic process includes analysis of assessment data; identification of the client's problem, health risks, strengths; and formulation of the diagnostic statements.

The diagnostic process includes analysis of assessment data; identification of the client's problem, health risks, strengths; and formulation of the diagnostic statements. Dental hygiene diagnoses improve communication among the dental hygienist, the client, and other health professionals.

Dental hygiene diagnoses improve communication among the dental hygienist, the client, and other health professionals. The related to part of the diagnostic statement provides the dental hygienist with direction regarding selecting interventions.

The related to part of the diagnostic statement provides the dental hygienist with direction regarding selecting interventions. The as evidenced by part of the diagnostic statement provides the dental hygienist with defining characteristics to evaluate the outcome of care.

The as evidenced by part of the diagnostic statement provides the dental hygienist with defining characteristics to evaluate the outcome of care. Dental hygiene diagnostic statements allow the dental hygienist to focus care on the client's unmet needs and individualize care.

Dental hygiene diagnostic statements allow the dental hygienist to focus care on the client's unmet needs and individualize care. Dental hygiene diagnostic statements should be clear, client centered, and based on reliable assessment data and should reflect only one problem (human need related to oral health and disease).

Dental hygiene diagnostic statements should be clear, client centered, and based on reliable assessment data and should reflect only one problem (human need related to oral health and disease).CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

1. Miller S. Dental hygiene diagnoses. RDH. 1982;2:46.

2. American Dental Education Association. Competencies for entry into dental hygiene. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:745.

3. American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA). Code of ethics. Chicago: ADHA, 1997.

4. American Dental Association Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental hygiene education programs. Chicago: Commission on Dental Accreditation, 1998.

5. Darby M.L. Collaborative model of practice: the future of dental hygiene. J Dent Educ. 1983;47:589.

6. Darby M.L., Walsh M.M. Application of the human needs conceptual model to dental hygiene practice. J Dent Hyg. 2001;74:230.

7. Price M.R. Nursing diagnosis: making a concept come alive. Am J Nurs. 1980;80:668.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..