CHAPTER 20 Dental Hygiene Care Plan and Evaluation

Explain the purpose of the planning phase in the dental hygiene process of care and the client’s role in care plan development.

Explain the purpose of the planning phase in the dental hygiene process of care and the client’s role in care plan development. Identify the sequence for developing a dental hygiene care plan and how each step relates to the dental hygiene diagnosis.

Identify the sequence for developing a dental hygiene care plan and how each step relates to the dental hygiene diagnosis.Care planning and evaluation are processes applied daily by the dental hygienist in practice. Both are integral to the process of care and dependent on the preceding phases of care, assessing and diagnosing. Integrating care planning and evaluating into dental hygiene care ensures a client-centered approach when treating clients. Dental hygienists must be competent in using principles of care planning and evaluation.

PLANNING

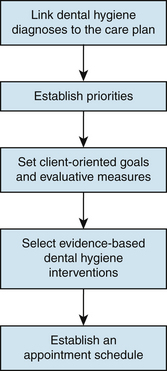

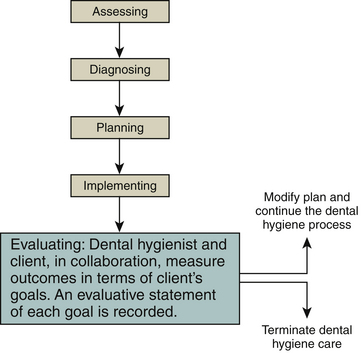

Planning is that phase of the process of care in which diagnosed client needs are prioritized, client goals and evaluative measures are established, and intervention strategies are determined (Figure 20-1). The purpose of the planning phase is to develop a plan of care that will result in the resolution of an oral health problem amenable to dental hygiene care, the prevention of a problem, or the promotion of oral and general health. Therefore care plan rather than treatment plan is intentionally used to denote the broad range of preventive, educational, therapeutic, and support services within the scope of dental hygiene practice. In keeping with standards of practice and evidence-based interventions, the dental hygienist engages the client in formulating a client-centered plan with clearly defined tangible outcomes.

To formulate a care plan the dental hygienist must effectively do the following:

Develop dental hygiene diagnoses, formulate client goals, and select supportive dental hygiene interventions.

Develop dental hygiene diagnoses, formulate client goals, and select supportive dental hygiene interventions.Dental Treatment Plan

The general dentist or dental specialist, develops a comprehensive dental treatment plan for the client. This plan includes the dental diagnosis; all essential phases of therapy to be carried out by the dentist, dental hygienist, and client to eliminate and control disease or promote health; and the prognosis. Components of a dental treatment plan are shown in Table 20-1. The dental hygiene care plan supports the overall dental plan. Ongoing collaboration between the dental hygienist, dentist, physician when warranted, and client is critical to attaining a successful outcome.

TABLE 20-1 Components of the Overall Dental Care Plan

| Components | Included in the Dental Hygiene Care Plan |

|---|---|

| Preliminary Phase: Emergency Care | |

| Relief of pain | |

| Laboratory tests for suspected pathology | |

| Emergency needs (e.g., treatment of periodontal or periapical abscess) | |

| Extraction of hopeless teeth | |

| Provisional replacement to restore function, as needed | |

| Phase I: Nonsurgical Therapy | |

| Client education and self-care instruction | x |

| Nutritional counseling (e.g., caries prevention, tissue healing) | x |

| Tobacco cessation | x |

| Fluoride and remineralization therapy | x |

| Placement of pit and fissure sealants | x |

| Therapeutic periodontal debridement | x |

| Hard-tissue desensitization | x |

| Correction of restorative and prosthetic irritative factors, excavation of caries | |

| Antimicrobial (anti-infective) therapy (local or systemic) | x |

| Occlusal therapy, minor orthodontics | |

| Selective coronal polishing | x |

| Evaluation of Response to Nonsurgical Therapy | |

| Reassessment of gingival and periodontal health, hard and soft deposits, host response | x |

| Review and reinforcement of self-care | x |

| Phase II: Surgical Therapy | |

| Periodontal surgery | |

| Implant surgery | |

| Endodontic therapy | |

| Phase III: Restorative Therapy | |

| Evaluation of response to restorative procedures (e.g., periodontal status, host response) | |

| Phase IV: Maintenance Therapy | |

| Supportive, preventive, and therapeutic periodontal maintenance therapy | x |

| Self-care education | x |

| Evaluation and recommendation of continued-care interval | x |

Adapted from Carranza FA, Takei HH: The treatment plan. In Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold, PR, Carranza FA, eds: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 10, St Louis, 2006, Saunders; Nield-Gehrig JS, Willmann DE: Decision-making during treatment planning. In Nield-Gehrig JS, Willmann DE: Foundations in periodontics for the dental hygienist, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2008, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Dental Hygiene Care Plan1

The dental hygiene care plan is the written blueprint that directs the dental hygienist and client as they work together to meet the client’s oral health goals. Primarily the plan increases the likelihood that the oral healthcare team will work collaboratively to deliver client-centered, goal-oriented care. The plan facilitates the monitoring of client progress, ensures continuity of care, serves as a vehicle for communication among healthcare professionals, and increases the likelihood of high-quality care (Box 20-1).

The dental hygiene care plan is written immediately after the assessment and diagnosis phases of the process of care and in conjunction with the overall dental treatment plan, prepared by the dentist. The care plan specifies the following:

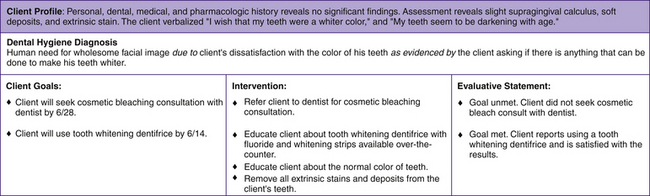

During the planning phase of care, dental hygiene diagnoses are prioritized and each component of the care plan is sequentially developed and linked to the dental hygiene diagnoses. Establishing this link between the dental hygiene diagnosis, client goals, and dental hygiene interventions is critical to the outcome of the care plan (Figure 20-2). Each dental hygiene care facility may have its own care plan format to document assessment findings, dental hygiene diagnoses, client-centered goals, dental hygiene interventions, appointment schedule, and an evaluative statement of outcome. Although formats may differ, the critical point is that these components are documented in the client’s permanent record and are followed to ensure high-quality dental hygiene care. The plan may use standardized abbreviations and key phrases as specified in the policy manual of the healthcare institution with which the dental hygienist is affiliated (Box 20-2). Figure 19-3 in Chapter 19 is a dental hygiene care plan form for documenting unmet human needs.

BOX 20-2 Characteristics of a Well-Written Dental Hygiene Care Plan

Sequence of Dental Hygiene Care Plan Development

Linking the Diagnosis and the Care Plan

A dental hygiene diagnosis is the foundation for care plan development. Basing dental hygiene care plans on the dental hygiene diagnosis, rather than on oral symptoms alone, ensures that care will be comprehensive and focused on client needs. A care plan may include a single or multiple dental hygiene diagnoses.

A complete dental hygiene diagnosis includes a statement of the problem (unmet human needs related to oral health), cause of the problem (contributor), and signs and symptoms of the problem (evidence). By focusing on the contributors and evidence of the unmet human needs, the clinician is able to develop client goals and intervention strategies that will best meet the need or eliminate the problem. Therefore client care is individualized, as opposed to the same routine care being provided to all. Because signs and symptoms related to dental hygiene problems may have numerous causes, interventions must be carefully selected to ensure that the fundamental cause is being addressed in dental hygiene care. For example, a dental hygiene diagnosis of an unmet human need in the area of wholesome facial image may result from the following:

Middle-aged client’s loss of self-esteem associated with mobile teeth and oral malodor from chronic periodontal disease

Middle-aged client’s loss of self-esteem associated with mobile teeth and oral malodor from chronic periodontal disease Nursing home resident who no longer wants to interact with friends and family because of lost dentures

Nursing home resident who no longer wants to interact with friends and family because of lost denturesThese problems require the establishment of unique client goals and dental hygiene interventions to resolve them. Figure 20-3 uses the aforementioned examples as the basis for establishing client-centered goals and planning dental hygiene interventions that focus on the unique needs of the client who is dissatisfied with his tooth color.

Establishing Priorities1

In collaboration with the dentist, the dental hygienist considers the dental and dental hygiene diagnoses and determines their urgency. Priorities are based on the degree to which the dental hygiene diagnosis does the following:

Threatens the client’s well-being; it is important to distinguish unmet needs that pose the greatest threat to client safety, health, and comfort from those that are non–life-threatening and/or related to a current oral disease

Threatens the client’s well-being; it is important to distinguish unmet needs that pose the greatest threat to client safety, health, and comfort from those that are non–life-threatening and/or related to a current oral diseaseOnce these criteria are applied to the dental hygiene diagnoses, the dental hygienist ranks the unmet human needs in priority to be addressed. Other than meeting the client’s unmet human need for safety (prevention of health risks), which in some instances requires emergency care or referral to a physician, dentists and dental hygienists would most likely identify the client’s ability to assume responsibility for oral health as a primary priority. Factors influencing how priorities are established include the following:

Setting Goals1

A client-centered goal is a desired outcome that the client aims to achieve through specific dental hygiene intervention strategies to satisfy an unmet human need. These goals reflect the signs and reported symptoms of the client’s unmet human needs. By setting goals based on the dental hygiene diagnosis, a relationship is established that enables the clinician and client to measure the extent to which goals have been achieved in terms of changes in the client’s initial signs and symptoms.

A client-centered goal may address cognitive, psychomotor, affective, or oral health status needs:

Cognitive goals target increases in the client’s knowledge. nPsychomotor goals reflect the client’s skill development and skill mastery.

Cognitive goals target increases in the client’s knowledge. nPsychomotor goals reflect the client’s skill development and skill mastery. Oral health status goals target the signs and symptoms of oral disease and reflect a desired health outcome achievable through dental hygiene interventions.

Oral health status goals target the signs and symptoms of oral disease and reflect a desired health outcome achievable through dental hygiene interventions.Knowledge and skill development alone may not correlate with client adherence to self-care. The client must internalize the desire and make modifications in behavior, so a variety of goals are necessary.

Writing Client-Centered Goals

Adopting a format for writing client-centered goals will simplify the task (Box 20-3). Each client-centered goal should have a subject, a verb, a criterion for measurement, and a time dimension for evaluation:

The verb is the action desired of the client to achieve the desired outcome; it is not the action of the dental hygienist.

The verb is the action desired of the client to achieve the desired outcome; it is not the action of the dental hygienist. Time dimension denotes when the client is to have achieved a goal. This target time may be a specific date or a statement (e.g., by next appointment, by the evaluation appointment, by end of treatment). Assigning a time frame to each client goal gives both the client and the clinician a point of reference. Clients need time to:

Time dimension denotes when the client is to have achieved a goal. This target time may be a specific date or a statement (e.g., by next appointment, by the evaluation appointment, by end of treatment). Assigning a time frame to each client goal gives both the client and the clinician a point of reference. Clients need time to:

BOX 20-3 Guidelines for Writing Client-Centered Goals

Goals evaluated too early restrict the clinician’s and the client’s ability to determine the impact of the care provided. At least one goal should be established for each dental hygiene diagnosis (Table 20-2).

TABLE 20-2 Some Dental Hygiene Diagnoses with Related Client-Centered Goals

| Dental Hygiene Diagnosis | Goals |

|---|---|

| Unmet human need for protection from health risk due to blood pressure elevated above normal limits as evidenced by a reading of 160/100 mm Hg. | Client will report having blood pressure evaluated by physician before rescheduled visit on 10/5. |

| Unmet human need in wholesome facial image due to use of spit tobacco as evidenced by client dissatisfaction with stained teeth. | Client will successfully complete a formal program for spit tobacco cessation by 12/30. |

| Unmet human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck due to subgingival biofilm accumulation in 4-mm pockets as evidenced by gingival bleeding. | Client will exhibit a gingival bleeding score of no more than 2 by 6/15. |

Involving the Client

Client goals are best established by the dental hygienist in collaboration with the client. Too often, individuals receiving care are referred to as “the Class II cavity preparation in treatment room 2” or “the advanced periodontal case at 4 pm.” These phrases communicate insensitivity to the individual, who is central in care. The oral healthcare professional who views the person as the focus of attention is more likely to establish a collaborative, co-therapeutic relationship with the client. This philosophy of care sets the stage for active client participation in identifying needs, readiness to change, priorities, goals, and interventions. Clients encouraged to participate in the process of care are more likely to communicate their wants, needs, and expectations than to relinquish decision making about their care to the dentist or dental hygienist. Individuals are more likely to express commitment to a care plan and their willingness to change if they shared in the development of goals, priorities, interventions, and appointment planning. Furthermore, when clients participate in care planning and believe that they have a key role in the success of the plan, compliance is augmented (Box 20-4).

At times, specific goals are valued more highly by the dental hygienist than by the client. When this occurs, the dental hygienist explains the professional judgment and decision, with a clear message that the client’s readiness to change, wants, and needs are equally important to the overall plan. Although these points are important for obtaining client commitment and adherence to the final dental hygiene care plan, dental hygienists must also keep in mind that respecting the client’s role as a co-therapist and partner in decision making is an effective risk management strategy for avoiding legal problems.

Selecting Dental Hygiene Interventions1

Dental hygiene interventions are the evidence-based strategies, products, and procedures that if applied will reduce, eliminate, or prevent the oral health problem. Interventions, like client-centered goals, are linked to the dental hygiene diagnosis. However, interventions address the factors contributing to the client’s human need.

Various factors may contribute to a client’s unmet need for a biologically sound and functional dentition, including but not limited to:

Therefore not every client with a high caries risk is cared for in the same way. For dental hygiene care to achieve the desired outcomes, evidence-based interventions must specifically address the factors contributing to the client’s unmet human need. For example, a dental hygiene intervention for “lack of knowledge about self-care for the prevention of dental caries” may include educating the client on the benefits of self-applied fluoride agents or teaching a parent with active caries about vertical transmission of the infectious disease to the children.

Evidence-based interventions enable the clinician and client to achieve the proposed client-centered goals and resolve the client’s unmet human need. Therefore professional dental hygiene care involves the careful tailoring of interventions to meet the unique needs of the client, as directed by the dental hygiene diagnosis.

Appointment Schedule

Once the interventions have been decided, they must be put into action at planned appointments. The appointment schedule becomes a guide for implementing the proposed interventions and specifies the following:

Number of visits and sequencing of interventions at appointments vary among clinicians and clients. The following are considered when an appointment schedule is planned:

When unmet client needs and proposed care plan goals are easily attainable, the related interventions may be implemented in one visit. When diagnoses, client goals, and interventions are complex, multiple appointments are indicated.

Scheduling time for educational interventions and the sequencing of self-care strategies must be given consideration during appointment planning. Too often client education is squeezed in at the end of an appointment as time permits. Effectively addressing the client’s cognitive, psychomotor, and affective needs will influence oral health outcomes and the client’s long-term responsibilities for self-care. Sequencing small increments of instruction into each visit may successfully shape the client’s self-care responsibilities. For example, multiple appointment care plans may spread client education over several visits to include time to review and reinforce previously introduced self-care behaviors. Box 20-5 suggests strategies for planning client self-care.

BOX 20-5 Strategies for Care Planning Self-Care Interventions

Care Plan Presentation

Before presenting the care plan to the client, the dental hygienist assesses the comprehensiveness of the plan by answering the following questions:

When the dental hygienist is satisfied with the completeness of the dental hygiene care plan, the plan is discussed with the client. The dental hygienist must explain all aspects of the care plan and involve the client in the discussion. Presentation and discussion of the dental hygiene care plan include the following:

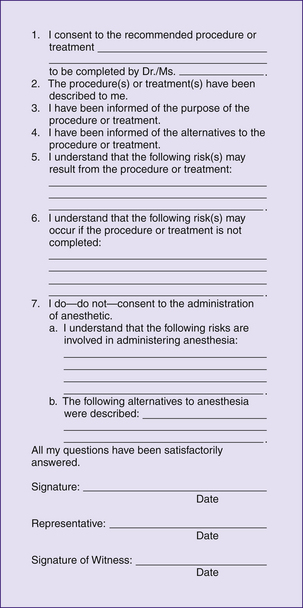

Once agreed on in writing by the client, the care plan becomes a legal contract between the dental hygienist and the client.

Most consumers expect to participate in decision making regarding their healthcare needs and know they have the right to accept or refuse services. If the care plan is to achieve the desired outcomes, both the clinician and client must support it. Therefore the care plan is presented to the client before preventive and therapeutic dental hygiene services are implemented. Failure to discuss the care plan with the client can result in services being performed without the client’s knowledge or informed consent. Also, the client may not recognize the importance of self-care or may have unrealistic expectations of care.

Informed Consent

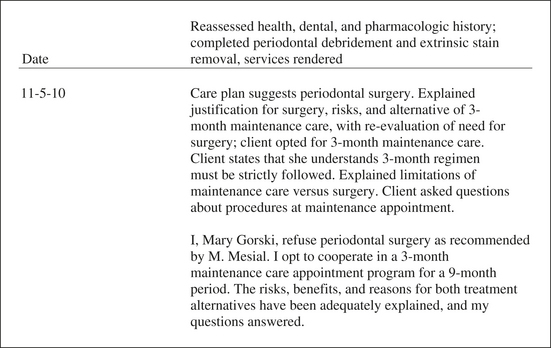

The process of informed consent is the client’s acceptance of care after a discussion with the healthcare provider regarding the proposed care plan and risks of not receiving care (Figure 20-4). Informed consent should not be viewed as a one-time activity but as an ongoing process in which the client is continuously reinformed and reminded of the terms of care. For informed consent to be achieved, the client must be knowledgeable about what the healthcare provider plans to do, have enough information to make a rational choice, and give permission for the plan to be carried out. The client must:

Give consent under truthful conditions (e.g., the consent cannot be obtained through fraud, deceit, misrepresentation, or trickery)

Give consent under truthful conditions (e.g., the consent cannot be obtained through fraud, deceit, misrepresentation, or trickery)In addition to the client being informed, the client must be legally competent to give consent for care. For example, in the case of a minor, consent must be given by the parent or legal guardian (healthcare decision maker). Although implied consent is given when a client voluntarily comes to the oral care setting and sits in the dental chair, this consent applies only to the assessment, diagnosis, and planning components of the dental hygiene process of care. The dental hygienist cannot assume that the client consents to any further care. The client’s expressed consent, which is given verbally or in writing, must be obtained for additional services to be implemented.

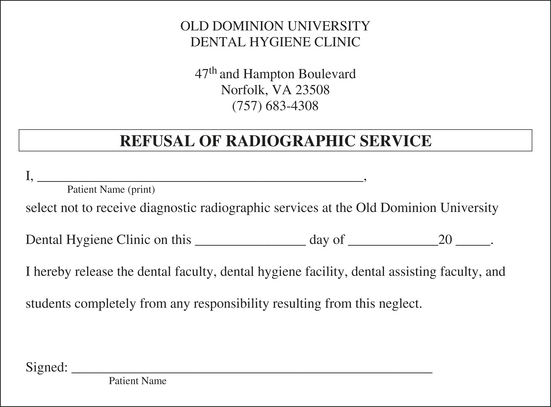

Informed Refusal

Given all information necessary for a client to make an informed decision, the possibility exists that a client may decline all or part of the proposed care plan, such as in the following situations:

Refusal to give up a behavior that increases the risk of periodontal disease progression (e.g., tobacco use)

Refusal to give up a behavior that increases the risk of periodontal disease progression (e.g., tobacco use)Although troubling, client refusal must be analyzed to determine how or why the client arrived at that decision. The clinician should engage the client in conversation, listen, and evaluate the client’s reasons for declining the services. At this time the clinician may choose to reopen the discussion of treatment needs. If after this discussion the client makes an informed refusal, the clinician should have the client sign a declaration of informed refusal (Figure 20-5). A copy of the refusal form can be given to the client, and a copy kept in the client’s record. Box 20-6 offers suggested client reasons for refusal of care, clinician actions, and documentation of informed refusal as a legal risk management strategy.

BOX 20-6 Client Reasons for Refusal of Care, Dental Hygiene Actions, and Documentation of Informed Refusal

| Client Reasons | Clinician Actions | Documentation |

|---|---|---|

In some situations the client may request care that, in the opinion of the dentist or dental hygienist, is unwarranted, inappropriate, or dangerous. If the dental hygienist is faced with this dilemma, she or he should refuse to provide the care and should encourage the client to seek a second professional opinion. As a rule, the client should never be allowed to dictate treatment.

See Procedure 20-1 for steps for dental hygiene planning.

Procedure 20-1 DENTAL HYGIENE CARE PLANNING

STEPS

EVALUATION

Goal of Evaluation

The goal of evaluation is to document achievement of desired therapeutic outcomes, that is, fulfillment of the client’s unmet human needs related to oral health and wellness. Evaluation is a critical component to the success of dental hygiene care. Specifically, evaluation allows the clinician to measure the short-term achievement of client-centered goals as well as to anticipate the client’s long-term prognosis in maintaining the goals achieved.

Although evaluation is indicated as the final phase of the dental hygiene process, evaluation is inherently linked to each phase of care (Figure 20-6). The foundation for establishing an evaluation strategy consists of the baseline signs and symptoms that support the dental hygiene diagnosis. Evaluation strategies are defined by the client-centered goals during the planning phase and applied during the implementation of care to support the client in achieving a desired outcome.

As the appointment schedule is put into action and interventions are implemented, the clinician continually measures client progress toward achieving the goals, that is, the desired outcome. Evaluation includes monitoring (reassessing) the client’s goal attainment, that is, oral self-care behaviors, indicators of oral health and disease, and adherence to professional recommendations. Both the dental hygienist and the client have an active role in this process. For example, a dental hygienist may have performed an intervention competently, but if the intervention or therapy was unsuccessful at helping the client achieve the desired goal, a new strategy must be considered. Therefore evaluation of a client’s progress toward achieving a desired outcome is ongoing so that the clinician can do the following:

Failure to evaluate the client can lead to what has been referred to as supervised neglect. Supervised neglect occurs when the client continues to require further dental hygiene care to achieve higher levels of oral wellness or to prevent or control oral disease progression, yet the client has been erroneously discharged from care thinking that a healthy state was achieved. Supervised neglect can occur in practices that have a one-approach-fits-all philosophy, manifested by employer statements such as the following:

In these situations the focus of care is task-oriented rather than client-centered. The emphasis is on completing the mechanics of a procedure, without considering the needs of the client, risk factors, and the influences of care on the client’s health status. In contrast, the focus of the dental hygiene process of care is the client and satisfying the client’s unmet human need. When the desired outcomes have been satisfied, a continued-care cycle is recommended to reactivate the process of care. Integrating evaluation into care demonstrates the dental hygienist’s commitment to achievement of the desired client outcomes. Evaluation does not meet every person’s need, but it provides assurance that unmet needs will not be overlooked or neglected.

Evaluation of Client-Centered Goals

Evaluation of client-centered goals determines whether dental hygiene care has achieved the client’s unmet human need. Evaluation methods should reflect the intent of the goal statement (e.g., cognitive, psychomotor, affective, or oral health status). An evaluation strategy may be as follows:

Showing the client clinical improvements in oral health (e.g., decrease in probing depth, elimination of bleeding points, no new carious lesions) (oral health status)

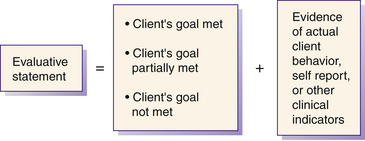

Showing the client clinical improvements in oral health (e.g., decrease in probing depth, elimination of bleeding points, no new carious lesions) (oral health status)Each client-centered goal is judged to determine the degree to which it has been achieved (Figure 20-7). Based on the new findings the dental hygienist determines one of the following outcomes:

A written evaluative statement includes the dental hygienist’s decision on the degree to which the goal was achieved and concrete evidence that supports the decision. This statement is recorded in the client’s permanent record, signed, and dated by the dental hygienist. Samples of evaluative statements as they relate to a dental hygiene diagnosis and client goal are displayed in Table 20-3.

TABLE 20-3 Sample of Evaluative Statements as Related to the Dental Hygiene Diagnosis and Client-Centered Goal Statements

| Dental Hygiene Diagnosis | Goal Statement | Evaluative Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Unmet human need for responsibility for oral health due to impaired physical ability as evidenced by a plaque-free index score of 30%. | 11/1 Goals met. Client reported using modified toothbrush twice daily, and plaque-free index has increased to 80%. | |

| Unmet human need for wholesome facial image due to wearing a denture and halitosis as evidenced by client’s concern with appearance of dentures, and client states that spouse complains she has frequent bad breath. | ||

| Unmet human need for conceptualization and problem solving due to a knowledge deficit about the periodontal disease process as evidenced by bleeding on probing and attachment loss. | Client will verbalize the periodontal disease process and identify oral biofilm as a prime causative agent by 9/20. | 9/20 Goal met. Client can describe the role of oral biofilm and the periodontal disease process. |

| Unmet human need for biologically sound dentition due to infrequent dental visits as evidenced by signs of four carious lesions. | Client will follow up on a referral made to the dentist of record and have the four carious lesions diagnosed and restored by 8/1. | 8/15 Goal not met. Client canceled dental appointment. |

| Unmet human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck due to inadequate self-care as evidenced by gingival bleeding. | Client will decrease bleeding by 75% by 5/8. | 5/10 Goal met. Client no longer shows clinical signs of gingival bleeding. |

Failure to evaluate the client’s status after care leaves the clinician unaware of the impact that the care may or may not have had. From a legal perspective, failure to evaluate the outcome of care may be grounds for negligence (malpractice). Unknown to the clinician and the client, the client’s oral health knowledge, behaviors, oral health status, or values may still be contributing to an oral health deficit. When a dental hygienist completes the cycle of care by measuring the extent to which client goals have been achieved and recommending continued care based on the outcome, the dental hygienist demonstrates professional practice.

Factors Influencing Client Goal Attainment

Characteristics of the client, dental hygienist, and clinical environment interact to enhance or hinder attainment of client goals. The astute dental hygienist identifies both positive and negative factors that may affect goal attainment. To facilitate the desired oral health outcome, positive factors are reinforced and negative factors managed.

A work environment that values high-quality healthcare and offers incentives for care that meet or exceed recognized standards of practice

A work environment that values high-quality healthcare and offers incentives for care that meet or exceed recognized standards of practiceTable 20-4 presents common variables that can detract from quality of care. Possible dental hygiene responses are presented to initiate thinking about overcoming factors that impede goal attainment.

TABLE 20-4 Factors That May Detract from the Quality of Dental Hygiene Care

Adapted from Taylor C, Lillis C, LeMone P, Tynn P: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2008, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Modifying or Terminating the Care Plan

When evaluation reveals that the client has made little progress toward goal attainment (i.e., goal partially met or goal not met), the dental hygienist reassesses the client’s readiness to change, attitudes, beliefs, and practices, and new findings are discussed with the dentist. Implications of these findings may lead to new diagnoses, revised goals, and alternative interventions. Client reassessment identifies barriers that continue to contribute to the client’s unmet human need, such as:

Care plan that does not specifically address the client’s goals and unique socioethnocultural characteristics; plan contains only general information

Care plan that does not specifically address the client’s goals and unique socioethnocultural characteristics; plan contains only general informationOnce it is clear why the client has failed to achieve goals, the evaluative statement can be used to redirect the care plan.

When client goals have been met and no new problems identified, the dental hygienist and client have achieved the outcome of care. The care plan is terminated, and responsibility for continued oral health falls on the individual. Written and verbal instructions are given to the client to take home, and signs and symptoms of any possible future problems should be clearly understood by the client.

Dental Hygiene Prognosis and Continued Care

At termination of the care plan, a new process-of-care cycle is recommended to the client for continued care. A continued-care interval that will support the client’s efforts to maintain the oral health status achieved during active therapy is determined. Each continued-care visit begins with the reassessment of the client’s oral health to provide evidence of the long-term success of the previous care plan and need for supportive care. The dental hygienist determines the cycle of periodic reassessment and continued care from the client’s prognosis.

The dental hygiene prognosis is contingent on the following:

A favorable prognosis occurs when risk for a new disease or recurrence of the previous conditions is low. A prognosis is guarded when risk for a new disease or recurrence of the previous condition is moderate to high.

Client-centered goals may be successfully achieved during active therapy; however, the prognosis may be guarded because of risk factors such as smoking or an uncontrolled systemic disease. Therefore the client and dental hygienist would select a frequent continued care interval to monitor oral health. Periodically the continued care plan is reviewed and adjusted to meet client needs. Continued-care appointments are scheduled at 2- to 12-month intervals based on client need.

Documentation of Services Rendered

A legal risk management strategy is to document the process of care in each client’s permanent dental record.2,3 Documentation that demonstrates a relationship among assessment, diagnosis, client-centered care plan, and evaluative statement of outcome is evidence that the services rendered reflected client needs. Documentation in the client record is the best defense against a client’s accusation of negligence (Figure 20-8).

Documentation of services rendered represents a written, legal record of all services performed for the client. Services should be recorded in the client record at the time they are performed. Entries are written in narrative form and describe relevant events of client care. All entries must be accurate and factual and provide enough detail to describe how the client progressed through the each phase of care to attain the proposed desired outcome. The narrative of services rendered and the client’s response to those services should be documented by the clinician who performed the services, signed, and dated. The example in Table 20-5 lists care planning and evaluation services that should be in the client’s record under “services rendered.”

TABLE 20-5 Guidelines for Documenting Planning and Evaluation in Client Records

Scenarios 20-1 and 20-2 and care plans are provided as examples.

SCENARIO 20-1 CLIENT WITH PLAQUE-INDUCED GINGIVITIS AND DENTAL CARIES AND SAMPLE DENTAL HYGIENE CARE PLAN

SCENARIO 20-1 CLIENT WITH PLAQUE-INDUCED GINGIVITIS AND DENTAL CARIES AND SAMPLE DENTAL HYGIENE CARE PLAN

Susie S., a healthy 19-year-old single woman without dental insurance, is a second-year student living at the local university. Her last preventive dental appointment was 2 years ago and included a prophylaxis and four bitewing radiographs. She brushes twice daily with fluoride toothpaste and flosses occasionally. Her chief complaint is “I hate the brown stain on my teeth.”

Clinical assessment reveals soft tissues within normal limits, Class I malocclusion with a slight anterior overbite, and crowding in mandibular anteriors. Gingival evaluation indicates localized slight papillary inflammation, sulcus depths within 3 mm, no attachment loss, and slight bleeding on probing in sextant 5. Plaque-free index is 85%. Dental examination indicates that 30 teeth are present, including partially erupted third molars (No. 17/ No. 32), extrinsic brown stain from coffee, and slight lingual and proximal calculus in sextant 5. No restorations are present; molars have pit-and-fissure sealants. Bitewing radiographs reveal Class II carious lesions on the mesial surface of teeth 2 and 15 and incipient carious lesions on the mesial surface of teeth 19 and 30. Susie reports that she drinks three to four cups of coffee with 2 teaspoons of sugar daily.

APPOINTMENT SCHEDULE

SCENARIO 20-2 CLIENT WITH PLAQUE-INDUCED GINGIVITIS MODIFIED BY SYSTEMIC FACTORS (PREGNANCY-ASSOCIATED GINGIVITIS) AND SAMPLE DENTAL HYGIENE CARE PLAN

SCENARIO 20-2 CLIENT WITH PLAQUE-INDUCED GINGIVITIS MODIFIED BY SYSTEMIC FACTORS (PREGNANCY-ASSOCIATED GINGIVITIS) AND SAMPLE DENTAL HYGIENE CARE PLAN

Renee B. is a 29-year-old married woman with a 5-year-old child. Renee, 8 months pregnant and in good health, is taking Pepcid at bedtime for heartburn. She reports that her pregnancy is becoming uncomfortable.

Her last oral prophylaxis was 6 months ago and included oral hygiene instruction. Full-mouth radiographs were taken 1 year ago, and findings were within normal limits. She brushes once daily and flosses sometimes. Her chief complaint is that “My gums are bleeding when I brush and I always have a bad taste in my mouth.”

Clinical examination reveals soft tissues within normal limits, Class I malocclusion, generalized moderate marginal gingival erythema and edema, moderately bulbous interdental papilla, spontaneous heavy bleeding on probing, and probing depths of 4 to 5 mm with no attachment loss evident. Plaque-free index is 75.8%. Generalized subgingival calculus can be felt with the explorer and probe; supragingival calculus is visible on the mandibular anterior lingual teeth and facial surfaceof the maxillary molars. Dental examination reveals 28 teeth present (third molars were previously extracted) and multiple Class I and II amalgam restorations.

APPOINTMENT SCHEDULE

| Phase I: Nonsurgical Therapy Appointment 1 (1 hour)—4/16 | CDT-2007-2008 Procedure Code |

|---|---|

| Update personal, health, dental, pharmacologic health history; measure vital signs; perform comprehensive oral evaluation: head and neck, dental, and periodontal; determine plaque-free index. | D0150 |

| Inform client of diagnosis and recommended care plan, including clinical findings, and obtain informed consent. | |

| D1330 | |

| Therapeutic periodontal debridement of quadrants 1 and 4. | D4341 |

| Appointment 2 (1 hour)—4/26 | |

| Update health history and measure vital signs. Assess tissue response to self-care and periodontal debridement of quadrants 1 and 4, determine plaque-free index. | |

| Self-care instruction: review toothbrushing if needed and instruct on flossing. | D1330 |

| Therapeutic periodontal debridement of quadrants 2 and 3. | D4341 |

| Phase I: Evaluation of Response to Nonsurgical Therapy Appointment 3 (1 hour)—5/10 | |

| Update health history and measure vital signs. Assess all quadrants for tissue response to self-care and periodontal debridement, determine plaque-free index. | D0120 |

| D1330 | |

| Adult prophylaxis to remove residual calculus (if any) and extrinsic stain with mild abrasive. | D1110 |

| Continued-care interval: 3 months. |

Additional scenarios are found on the  website:

website:

See Procedure 20-2 for steps for evaluation of care.

Procedure 20-2 EVALUATION OF CARE

STEPS

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Inherent in the process of care is the legal and ethical responsibility of healthcare providers to do the following:

Inherent in the process of care is the legal and ethical responsibility of healthcare providers to do the following: Keep adequate client records that are legible, dated, and signed with the title of the individual making the entry.

Keep adequate client records that are legible, dated, and signed with the title of the individual making the entry. Document clinical and radiographic findings as evidence that the diagnosis and care plan are based on client needs.

Document clinical and radiographic findings as evidence that the diagnosis and care plan are based on client needs. Provide evidence of medical consultation, when needed, and written response with information requested.

Provide evidence of medical consultation, when needed, and written response with information requested.KEY CONCEPTS

A dental hygiene care plan is an evidence-based, client-centered written proposal to meet the unmet human needs of a client that are related to oral health and within the scope of dental hygiene practice.

A dental hygiene care plan is an evidence-based, client-centered written proposal to meet the unmet human needs of a client that are related to oral health and within the scope of dental hygiene practice. The care plan reflects the dental hygiene diagnosis, client-centered goals, dental hygiene interventions, detailed appointment schedule, and expected outcomes.

The care plan reflects the dental hygiene diagnosis, client-centered goals, dental hygiene interventions, detailed appointment schedule, and expected outcomes. A well-formulated and executed care plan will increase the likelihood of a positive outcome in the dental hygiene care process.

A well-formulated and executed care plan will increase the likelihood of a positive outcome in the dental hygiene care process. Evaluation is a critical component of the dental hygiene process and a necessary step to document evidence of care plan success in achieving a desired outcome in the client’s oral health status.

Evaluation is a critical component of the dental hygiene process and a necessary step to document evidence of care plan success in achieving a desired outcome in the client’s oral health status.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Client Profile 1: James W., a 50-year-old man, is a long-haul truck driver who is taking hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension, drinks two to three cups of coffee per day, and smokes one pack of cigarettes per day.

Dental History: James’ last dental appointment was 1 month ago for extraction of tooth 2, which was periodontally involved; before this time, 10 years had passed since his last dental appointment. He brushes once daily with fluoride toothpaste, and his chief complaint is that “I have pain in the upper left molar region, and I do not want to lose any more teeth.”

Assessment: Clinical examination reveals nicotine stomatitis, Class II malocclusion with a moderate overbite, and a coated tongue. Dental examination reveals missing third molars and maxillary right second molar; generalized moderate brown stain; slight subgingival calculus; localized moderate supragingival calculus in sextant 5; and Class I and II amalgam restorations.

Gingival and periodontal assessment findings reveal generalized moderate marginal inflammation, generalized slight recession; localized moderate recession on facial surfaces of sextants 3 and 4; bleeding on probing; pocket depths of 3 to 5 mm, with attachment loss at 4 to 5 mm; Class II and III furcations and Class I mobility on teeth No. 14 and No. 15. Full-mouth periapical and vertical bitewing radiographs show evidence of a recurrent carious lesion on tooth 30 and root caries on the distal surface of tooth 14, generalized moderate horizontal bone loss in molar regions, and localized vertical bone loss on the distal surface of tooth 14.

Client Profile 2: Mrs. Wilton is a 57-year-old woman who has been married for 35 years. She cares for her two grandchildren, Dayne, age 2, and Katie, age 4, 3 days per week while the children’s mother works.

Health History: Mrs. Wilton has type 2 diabetes, controlled by oral hypoglycemic medication and diet, and hypertension, controlled by Avapro. She sees her physician on a regular basis for her diabetes and hypertension.

Dental History: Mrs. Wilton has not seen a dentist in 7 years. She is a client of record at the local University dental hygiene clinic where she has been treated every 4 to 6 months for the past 4 years because she does not have dental insurance. At each past continued-care appointment, she has had generalized type 2 I chronic periodontal disease. Each past care plan has indicated the dental hygiene diagnosis “Human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck due to inadequate oral biofilm management by the client and generalized moderate to heavy calculus as evidenced by generalized bleeding on probing.” The care plans have emphasized the same intervention strategies, i.e., modified Bass toothbrushing and flossing followed by a series of quadrant root debridement appointments. Appointment notes indicate that the client keeps her scheduled appointments and properly demonstrates recommended toothbrushing and flossing skills; however, she states she does not like to floss.

Supplemental Notes: Mrs. Wilton arrives today at the dental hygiene clinic for a scheduled continued-care visit. No changes have occurred in her health history; all medications are taken as prescribed; blood pressure is within normal limits. Assessment findings reveal no change in oral health status since the last continued-care appointment. Reason for her visit: “to have my teeth cleaned.”

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedures presented in this chapter.

1. Darby M, Walsh M : A pplication of the human needs conceptual model to dental hygiene practice. Presented at the 14th International Symposium on Dental Hygiene, Florence, Italy, July 1998 .

2. Vaughn L. Common areas of legal risk. Access. 2007;21:37.

3. Vaughn L. Common areas of legal risk. Access. 2007;21:49.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..