CHAPTER 34 Tobacco Cessation

Tobacco is the chief avoidable cause of illness and death in the United States. Each year over 450,000 people die from tobacco-related diseases.1 It is imperative that all healthcare providers assess and treat tobacco use to increase the likelihood of tobacco cessation. Tobacco cessation occurs when a person stops tobacco use with the goal of achieving permanent abstinence. Although some tobacco users achieve permanent abstinence in an initial quit attempt, the majority persist in tobacco use and typically cycle through multiple periods of abstinence and relapse (reverting to regular tobacco use). All tobacco contains nicotine, a highly addictive drug that creates physical and psychologic dependence on tobacco. Tobacco dependence makes it difficult for individuals to stop tobacco use even if they have health problems. Tobacco dependence is a chronic disorder characterized by a vulnerability to relapse that persists for months and even years. Relapse is likely because of the chronic nature of tobacco dependence, not clinicians’ personal failure nor a failure of their clients. The relapsing nature of tobacco dependence requires the need for ongoing rather than just acute care.2 As with other chronic disorders (e.g., periodontal disease, hypertension, diabetes), dental hygienists encountering tobacco-dependent clients are encouraged to provide ongoing advice, counseling, and referral. Despite the potential for relapse, however, numerous effective treatments are available to promote tobacco cessation.

SYSTEMIC HEALTH EFFECTS

All tobacco products contain cancer-causing chemicals such as N-nitrosamines, aromatic hydrocarbons, and polonium 210. In addition, smoking produces tar, carbon monoxide, and other chemically destructive byproducts present in tobacco smoke. During the inhalation process, smokers absorb nicotine, cancer-causing chemicals contained in tobacco, and the toxic by-products of burning tobacco through the lungs. These toxins enter the bloodstream and are distributed to tissues throughout the body. This exposure to toxic chemicals threatens the health of smokers. For example, smoked tobacco is responsible for 87% of lung cancers, and, on average, one half of smokers lose 20 to 25 years of their life expectancies.3 Box 34-1 lists numerous adverse systemic effects associated with tobacco use.

BOX 34-1 Systemic Effects of Tobacco Use

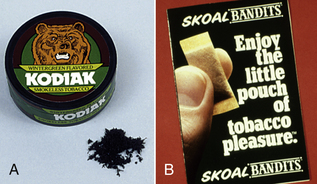

Oral snuff and chewing tobacco, also known as spit (smokeless) tobacco, also are associated with cancer and cardiovascular disease. Oral snuff (known as “snus” in Sweden and some other countries) is a finely ground tobacco leaf, packaged either loose or in a tea bag–like sachet (Figure 34-1). Snuff users place a small amount of oral snuff between the cheek and gum. Chewing tobacco is a more coarsely shredded tobacco leaf. Tobacco chewers place a “chaw” of looseleaf tobacco, or a “plug” of compressed tobacco, in the cheek (Figure 34-2). Oral snuff and chewing tobacco users spit out the tobacco juices and saliva generated; sometimes they swallow them.

Most spit tobacco products contain much larger amounts of nitrosamines (cancer-causing chemicals) than those legally allowed in other consumable products. Moreover, manufacturers control the amount of free nicotine available for uptake into the body by controlling the pH of their products. Free nicotine is ionized nicotine that passes rapidly through the oral mucosa into the bloodstream and into the brain. Because free nicotine is formed in an alkaline environment, the higher the pH of a spit tobacco product, the more available free nicotine. For example, at a neutral pH of 7.0, there is no free nicotine available; however, at a pH of 8.0, about 60% of the nicotine is ionized and available for use by the body to create dependence. The amount of free nicotine available in spit tobacco products is controlled by manufacturers through the addition of alkaline buffering agents. Usually new users start with products with low amounts of free nicotine to avoid the unpleasant side effects of nicotine toxicity (e.g., nausea and vomiting). Eventually, however, because of nicotine dependence, many need to use products with higher amounts of free nicotine. Table 34-1 shows the pH of popular oral snuff brands and the percentage of free nicotine available in each. Brands with high levels of available free nicotine are very addictive, making it difficult for individuals to quit.

TABLE 34-1 The pH and Percentage of Free Nicotine in Oral Snuff Brands

| Brand | PH | % Available Free Nicotine |

|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen | 8.0 | 57 |

| Skoal Fine Cut | 7.5 | 29 |

| Skoal Long Cut (varying brands) | 7.2 | 23 |

| Skoal Bandits | 5.4 | <1 |

From Djordjevic MV, Hoffmann D, Glynn T, Connolly GN: US commercial brands of moist snuff, 1994, I: assessment of nicotine, moisture, and pH, Tob Control 4:62, 1995.

ORAL HEALTH EFFECTS

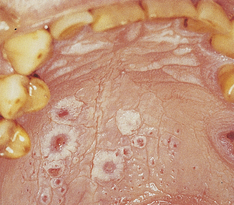

The oral effects of tobacco use3 are listed in Box 34-2. The dental hygienist points out and discusses with clients the visible effects of their tobacco use and documents all relevant findings. For example, a smoker may have nicotine stomatitis (Figure 34-3) on the palate, and smokers are three to six times more likely than nonsmokers to develop periodontal disease.4 In addition, almost half of spit tobacco users have oral mucosal lesions and gingival recession associated with use (Figure 34-4). The oral mucosal lesions are typically characterized as being white, hyperkeritinized, and wrinkled and often disappear if tobacco use is terminated at an early enough stage.

Figure 34-4 Gingival recession and hyperkeratosis of the vestibular mucosa that developed after the use of chewing tobacco.

(From Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 10, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.)

Table 34-2 lists actual or potential unmet human needs related to tobacco use. In addition, the clinical manifestations of tobacco-induced periodontal disease and their biologic bases are presented in Table 34-3. All forms of tobacco are associated with oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal cancer.3 The long-standing relationship between oral cancer and tobacco use is well documented (see Chapter 44). Concomitant use of alcohol with tobacco increases the risk of oral cancer tenfold. Seventy-five percent of oral and pharyngeal cancers are attributed to tobacco and/or heavy alcohol use.3 Consequently, during health history assessment, clients are questioned about alcohol use, tobacco use, and sun exposure, all risk factors for head, neck, skin, and lip cancers. The extraoral and intraoral examination must be thorough and all tissue changes noted in the client’s chart.

TABLE 34-2 The Tobacco-Using Client and the Human Needs Model

| Human Needs | Actual or Potential Deficits∗ |

|---|---|

| Wholesome facial image | Tooth staining, halitosis, periodontal disease, missing teeth, facial wrinkling |

| Protection from health risks | Tobacco-related illness, e.g., heart disease, high blood pressure, cancer; delayed wound healing |

| Biologically sound and functional dentition | Missing teeth, abrasion, erosion, chewing difficulties, abscesses |

| Skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck | Oral lesions, oral cancer, attachment loss, and pocket depths of 4 mm or greater |

| Freedom from fear and stress | Withdrawal due to nicotine addiction |

| Responsibility for oral health | Inadequate ownership of personal oral health and hygiene |

| Conceptualization and problem solving | Misconceptions and lack of knowledge about systemic and oral effects of tobacco use |

∗ All unmet human needs can be addressed by efficient and effective tobacco interventions.

TABLE 34-3 Tobacco-Induced Periodontal Tissue Changes

| Tissue | ||

|---|---|---|

| Changes with Use | Biologic Bases for Changes | Tissue Changes with Abstinence |

| Paler tissue color | Increased vasoconstriction | Increased blood flow |

| Decreased bleeding | Oxygen depletion | Initially, more bleeding, erythema |

| Thickened fibrotic consistency; minimal erythema relative to extent of disease | Compromised immune response | Healthier consistency and anatomy |

| Gingival recession around anterior sextants | Increased collagenase production | |

| Greater probing depths, bone and attachment loss, furcation invasion | Reduction of bone mineral; impaired fibroblast function | Stabilization of attachment levels |

| Refractory status: continued use | Impaired wound healing |

CHALLENGES TO SUCCESSFUL TOBACCO CESSATION

Findings from a national survey report that 70% of smokers want to quit. Each year approximately 46% try to quit, but less than 10% achieve abstinence. Among smokers who attempt to quit, 60% relapse within the first 7 days of quitting and 70% relapse within the first month. Most tobacco users require multiple attempts at stopping their tobacco use before they are ultimately successful.2 Addiction to nicotine makes it very difficult to quit.

NICOTINE ADDICTION

Hallmarks of nicotine addiction are as follows:

Helping a tobacco-using client achieve abstinence requires an understanding of nicotine addiction. Aspects of nicotine addiction can be categorized as physical, psychologic, sensory, behavioral, and social.

Physical Aspects

The physical aspects of nicotine addiction include reinforcing effects, tolerance, and physical dependence.5

Reinforcing Effects

Nicotine causes the brain to release chemicals such as dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, vasopressin, serotonin, and beta-endorphins. These chemicals produce effects in the brain that cause the user to experience pleasure, anxiety and tension reduction, a sense of well-being when one feels down, arousal (perks one up when tired), short-term memory improvement, and appetite suppression. These neurochemical rewards that nicotine provides a tobacco user are called reinforcing effects.5 These reinforcing effects reward tobacco users and increase their desire to continue using tobacco (Table 34-4).

TABLE 34-4 Effects of Chemicals Released by the Brain When Exposed to Nicotine

| Chemical | Effect |

|---|---|

| Dopamine | Pleasure |

| Serotonin | Mood modulation |

| Beta-endorphin | Anxiety reduction |

| Acetylcholine | Cognitive enhancement; perks one up if tired |

| Vasopressin | Short-term memory enhancement |

| Norepinephrine | Appetite suppression |

Tolerance

With chronic exposure to nicotine, brain cells adapt to compensate for the actions of nicotine. This process is called neuroadaptation. Tolerance results from neuroadaptation, so that over time a given level of nicotine eventually has less of an effect on the brain and a larger dose is needed to produce the rewarding effects that lower doses formerly produced. Thus the longer clients use tobacco, the more nicotine they need to achieve the desired reinforcing effects.5

Physical Dependence

Although the brain adapts to function normally in the presence of nicotine, it also becomes physically dependent on nicotine for that normal functioning. When nicotine is not available, the brain function becomes disturbed, resulting in withdrawal symptoms (Table 34-5). Symptoms peak within 12 to 24 hours and last 2 to 4 weeks if tobacco use is discontinued. Not all individuals experience withdrawal symptoms, and the degree of discomfort from withdrawal also varies. In general, however, the nicotine withdrawal symptoms produced by nicotine abstinence necessitates clients to continue to increase their tobacco use to prevent withdrawal symptoms. Therefore, although initially individuals use tobacco for the reinforcing effects of pleasure, enhanced short-term memory, and mood modulation, often tobacco use ends up dominating their lives. Because tobacco use produces tolerance and physical dependence, it results in addiction and loss of control over use. This loss of control is due to the individual’s intense need to use tobacco to self-medicate to prevent withdrawal symptoms.5 In general, the highly dependent tobacco user poses the greatest challenge to cessation efforts, usually requiring pharmacotherapy combined with intense behavioral counseling.

TABLE 34-5 Nicotine Withdrawal Symptoms and Suggested Behavioral Coping Strategies

Modified from Severson H: Enough snuff: a guide to quitting smokeless tobacco, Point Richmond, Calif, 1997, Applied Behavior Science.

Psychologic, Behavioral, Sensory, and Sociocultural Aspects

Psychologic, behavioral, sensory, and sociocultural aspects of nicotine addiction also sustain tobacco use.5

Psychologic Aspects

Psychologic aspects of nicotine addiction relate to a tobacco-using client’s need to use tobacco to cope with stress and/or depression. Many tobacco users perceive their tobacco as “a friend” that is always with them, providing a sense of comfort and security. Tobacco use also initially may be used as passive entertainment to decrease boredom or as a diversion from a strife-filled existence.

Behavioral Aspects

Behavioral aspects of nicotine addiction relate to learned anticipatory responses that tobacco users develop from having experienced various forms of gratification from tobacco use in certain previous situations.5 When a tobacco user encounters these environmental cues, they serve as situational reminders of tobacco use (e.g., after a meal or when drinking alcohol) and its associated pleasure or other reinforcing effects. These cues or stimuli then generate a strong urge to use tobacco known as a learned anticipatory response. Such learned anticipatory responses can last 6 months or longer after physical dependence has been overcome and often are responsible for relapse that occurs beyond the first 2 to 4 weeks of cessation. For successful cessation, tobacco users have to learn to anticipate situational cues that will trigger the desire to use tobacco and to plan ahead to identify alternative rewards and ways to cope with these trigger situations so as to remain tobacco-free.

Sensory Aspects

Puffing on a cigarette or having a dip of a specific size and texture in one’s mouth provides oral gratification, which relates to the sensory aspect of nicotine addiction. Because of the sense of well-being this oral gratification provides, the use of nontobacco oral substitutes (e.g., chewing gum, sunflower seeds) is important to the quitting process.5 In addition, because nicotine is an appetite suppressant, individuals often increase their food intake when they reduce their nicotine exposures. Individuals who successfully stop their tobacco use on average gain 10 pounds. Drinking a lot of water, getting exercise, and eating a balanced low-fat diet can help avoid this weight gain.6

Sociocultural Aspects

Sociocultural aspects of nicotine addiction that pose challenges to cessation include peer pressure, the influence of family members and significant others who use tobacco, and a social network that supports and accepts tobacco use. Tobacco users trying to stop their tobacco use often need to avoid situations where they will be tempted to use until they are secure that they can refrain from using tobacco in these situations.

HELPING CLIENTS BECOME TOBACCO-FREE

When one assists clients in their efforts to stop using tobacco, all aspects of nicotine addiction must be confronted and alternative coping strategies identified. Being supportive and assisting the client with problem solving are critical to promoting tobacco cessation.

The Five A’s Approach

A general framework for helping clients in the healthcare setting to become tobacco-free is the Five A’s approach, a strategy developed by the National Cancer Institute and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.2 The Five A’s approach to tobacco cessation involves asking clients about tobacco use, advising users to quit, assessing readiness to quit, assisting with the quitting process, and arranging follow-up. Table 34-6 provides sample language for the dental hygienist to use while performing components of the five A’s. The Five A’s approach serves as a model for brief, effective interventions that have been successfully implemented in both medical and dental care environments.2,7 Each component of the Five A’s approach is described briefly in the following sections. A team approach involving all office staff facilitates the Five A’s approach.

TABLE 34-6 The Five A’s Approach to Tobacco Cessation: Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange2

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Treating tobacco use and dependence, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Publication No. 69-0692, Washington, DC, 2000, U.S. Government Printing Office.

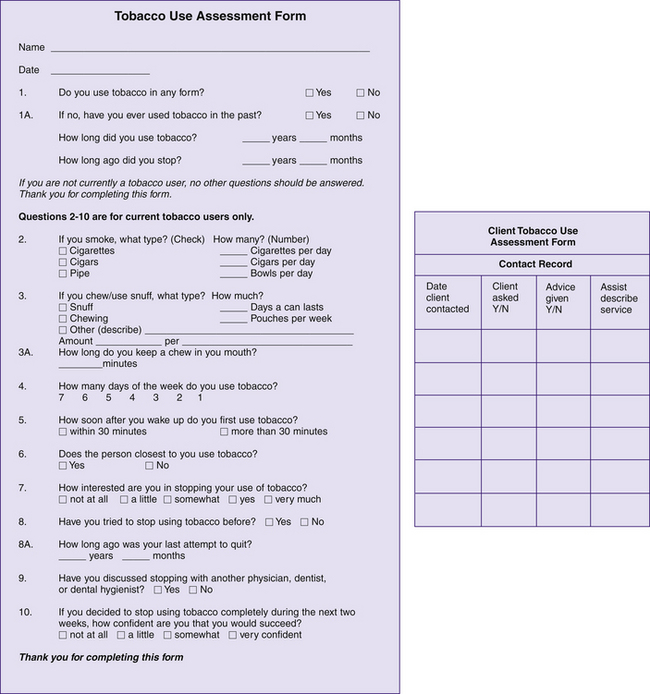

Ask

It is important to identify all tobacco users systematically at every visit. This identification occurs by using an in-office system such as including an item on the health history form that asks about tobacco use and having all tobacco users complete a separate Tobacco Use Assessment Form, such as the one presented in Figure 34-5, for inclusion in the client-care record. In addition, the dental hygienist verbally asks each client about tobacco use (see Table 34-6 for suggested language). Cues or prompts, such as chart stickers or codes on the client schedule, are recommended to remind the hygienist to ask each client.

Advise

The dental hygienist advises all tobacco users to stop their tobacco use to protect their current and future health. Such advice should be clear, unequivocal, nonjudgmental, and related to something immediately relevant to the client (see Table 34-6 for suggested language). For example, if clients have oral mucosal tissue changes as a result of tobacco use (see Figure 34-4), the dental hygienist points out the tissue changes to them in their own mouths and incorporates this information to personalize advice to stop using tobacco. Personalizing cessation advice with findings visible to the client provides a “teachable moment” that can motivate the client to decide to make a quit attempt.2 During the advice component of the Five A’s approach, it is very appropriate to discuss actual and potential adverse health effects associated with tobacco use. After the advice component, however, the dental hygienist replaces discussion of negative health effects with discussions about the benefits of quitting to enhance motivation to stop tobacco use (Box 34-3).

BOX 34-3 Benefits of Stopping Tobacco Use

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Surgeon General report on the health benefits of smoking cessation, 1990.

Assess

For all clients who report tobacco use, the dental hygienist determines which tobacco users are willing to make a quit attempt by assessing their readiness to quit. To assess readiness to quit, the dental hygienist simply asks clients if they would like to stop their tobacco use in the next month. The concept of readiness to quit relates to the stages of change theory.8 According to this theory, tobacco cessation (or any other behavior change) involves movement through a series of five stages. These stages are precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Precontemplation is the stage of change where the client has no thought of stopping tobacco use. Using tobacco is not viewed by the client as a problem. Contemplation is the stage where clients think they should stop tobacco use some day, but not in the next month. Preparation is the stage of change where clients are willing to set a quit date and to begin changing their behavior and thinking related to tobacco use in preparation for quitting in the next month. Action is the stage where clients have stopped their tobacco use for less than 6 months. Maintenance is the stage of change where clients have stopped tobacco use for more than 6 months. Precontemplators and contemplators will respond in the negative when the dental hygienist asks if they would like to try to quit their tobacco use in the next month. It is important for the dental hygienist not to take this rejection personally but to recognize and understand that the client simply is not yet ready to quit. Even sound advice coupled with demonstrating the damaging effects of tobacco use may not move the client who is in precontemplation or contemplation to take action to quit tobacco use (preparation). Only when clients perceive that the personal benefits of stopping tobacco use outweigh the benefits of continued use will they make a decision to quit. Nevertheless, personalized advice to quit delivered in a caring nonjudgmental manner often moves a client in the precontemplation stage to the contemplation stage of change. This shift in stage of change constitutes success because such movement is in the direction of making a decision to quit some day. Clients’ readiness to quit determines the appropriate strategy for assisting them with the quitting process.

As individuals attempt to stop tobacco use, relapse (reverting to regular tobacco use) followed by recycling through the stages of change occurs frequently. When relapse occurs the client will return to the contemplation or precontemplation stage before attempting to quit again. The dental hygienist encourages clients to view relapse as a learning opportunity because what is learned from relapse can be applied to the next quit attempt. See Table 34-7 for a summary and suggested dental hygiene interventions.

TABLE 34-7 Stages of Readiness to Change8

| Stage | Related Client Characteristics and Behavior | Dental Hygiene Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Precontemplation | No thought of quitting in the next 6 months | Dispense educational material on reasons for quitting. Client may be defensive when confronted with the information. |

| Contemplation | Thinking about quitting within the next 6 months | Dispense educational material, and discuss pros and cons of quitting. Ambivalence may be present, but clients will more likely accept information as they are developing more belief in the value of change. |

| Preparation | Willing to set a quit date in the next month and to make small changes in preparation for quitting in the next month | Client believes advantages outweigh disadvantages of behavior change. May need assistance in planning for the change. Implement cessation counseling. |

| Action | Actively engaged in strategies to change behavior. This stage may last up to 6 months. May have stopped using tobacco, but for less han 6 months | |

| Maintenance | Has stopped using tobacco for more than 6 months. Sustained change over time. This stage begins 6 months after action has started and continues indefinitely | Praise. Discuss relapse prevention. Changes need to be integrated into the client’s lifestyle. |

| Relapse | Using tobacco again and may reach higher levels than before | Set new quit date and begin cycle again. |

Adapted from Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC: Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors, Prog Behav Modif 28:184, 1992.

Assist

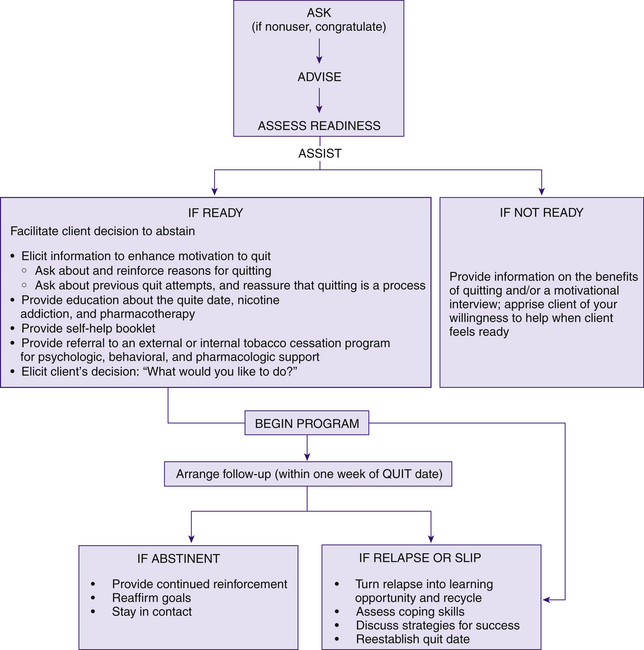

The manner in which the dental hygienist assists clients in quitting tobacco depends on their readiness to quit (see Figure 34-6 for a tobacco intervention flow chart and the detailed discussion that follows). Whether or not clients are ready to quit, it is critical that the dental hygienist engage them by applying patient-centered communication.9,10

Characteristics of patient-centered communication are as follows7,9:

Collaborating, not persuading: The dental hygienist–client relationship involves a partnership that honors the client’s experience and perspectives. The dental hygienist seeks to create a positive interpersonal atmosphere that is conducive to change, but not coercive.

Collaborating, not persuading: The dental hygienist–client relationship involves a partnership that honors the client’s experience and perspectives. The dental hygienist seeks to create a positive interpersonal atmosphere that is conducive to change, but not coercive.Arrange

Scheduling a follow-up contact is the fifth A, and it is comparable to the evaluation phase of the dental hygiene process of care. In follow-up contacts, the dental hygienist checks in on where clients are in their thinking about quitting, or on their progress in coping with the quitting process. For those clients who have made an unsuccessful quit attempt, modifications (e.g., new quit date, other pharmacologic adjuncts, different coping mechanisms, as described in later sections) may be introduced. New goals may be set.2,10

Assisting Clients Who Are Not Ready to Quit

For clients who are not ready to stop their tobacco use within the next month, the primary goal is to help them to think about the benefits of using tobacco versus the benefits of stopping tobacco use. (Once the benefits of stopping outweigh the benefits of using, the client will make a decision to quit.) For this goal to be accomplished, a brief intervention or a motivational interview is recommended.

The Brief Intervention

The brief intervention takes less than 3 minutes to perform. The goal is to communicate acceptance of the client’s stage of change and to provide information on the benefits of stopping tobacco use.10 When a client refuses an offer of help to stop tobacco use in the brief intervention, the dental hygienist does the following10:

States, “I understand that you are not ready to stop smoking now, but if you don’t mind I would like to give you some information on the benefits of stopping for you to consider” (see Box 34-3). This statement communicates to the client that he or she has been heard and that the dental hygienist understands that the client is not ready to stop now. In addition, the dental hygienist offers information on the benefits of quitting to help move the client to the next stage of change and in the direction of making a decision to quit some day.

States, “I understand that you are not ready to stop smoking now, but if you don’t mind I would like to give you some information on the benefits of stopping for you to consider” (see Box 34-3). This statement communicates to the client that he or she has been heard and that the dental hygienist understands that the client is not ready to stop now. In addition, the dental hygienist offers information on the benefits of quitting to help move the client to the next stage of change and in the direction of making a decision to quit some day.The Motivational Interview

In addition to applying the brief intervention as noted previously, the dental hygienist may judge that the client would be open to a motivational interview.9 The motivational interview is a form of patient-centered communication to help clients get “unstuck” from the ambivalence that traps them in their tobacco use so they can start the change process.9 Ambivalence is a common human experience and is a normal stage in the process of change (i.e., contemplation). Once ambivalence is resolved, little else may be required for the client to decide to stop tobacco use. It is interesting to note, however, that attempts to force resolution of ambivalence by direct persuasion to stop tobacco use can lead to strengthening the very behavior that the clinician intended to diminish. For example, nagging may increase rather than decrease smoking. The theory of psychologic reactance9 predicts an increase in the rate and attractiveness of “problem” behavior if a person perceives that his or her personal freedom is being infringed or challenged. Therefore discovering and understanding a client’s motivations for tobacco use are important first steps toward promoting change.

Principles

Four general principles that underlie motivational interviewing are as follows9:

Express empathy: The attitude is one of acceptance. The dental hygienist respectfully listens to the client with a desire to understand his or her perspectives without judging, criticizing, or blaming. The client’s perspectives are responded to as understandable and valid. Paradoxically, acceptance of people “as they are” seems to free them to change, whereas insistent nonacceptance tends to immobilize the change process.

Express empathy: The attitude is one of acceptance. The dental hygienist respectfully listens to the client with a desire to understand his or her perspectives without judging, criticizing, or blaming. The client’s perspectives are responded to as understandable and valid. Paradoxically, acceptance of people “as they are” seems to free them to change, whereas insistent nonacceptance tends to immobilize the change process. Develop discrepancy: Change is motivated by a perceived discrepancy between smoking and important personal goals or values (e.g., “So you enjoy smoking, but you worry about the negative effect your smoking may have on your teenage son”).

Develop discrepancy: Change is motivated by a perceived discrepancy between smoking and important personal goals or values (e.g., “So you enjoy smoking, but you worry about the negative effect your smoking may have on your teenage son”).Tools

The goal of motivational interviewing is to have the client voice the arguments for change, known as change talk. Change talk includes reasons for concern and the advantages of change (i.e., the good things to be gained.) Tools for eliciting change talk include four strategies referred to by the acronym OARS.9,10 These tools are as follows:

Open-ended questions: Open-ended questions are questions that cannot be answered by a simple “yes” or “no” response. Open-ended questions begin with asking “What,” “How,” or “Why” and require the client to explain the response. During the motivational interview the dental hygienist allows the client to express himself or herself and explores both sides of the client’s ambivalence about tobacco use by asking open-ended questions (e.g., “What do you like about tobacco use?” “What is the downside?” “So what kind of roadblocks come to mind when you think about stopping smoking?”)

Open-ended questions: Open-ended questions are questions that cannot be answered by a simple “yes” or “no” response. Open-ended questions begin with asking “What,” “How,” or “Why” and require the client to explain the response. During the motivational interview the dental hygienist allows the client to express himself or herself and explores both sides of the client’s ambivalence about tobacco use by asking open-ended questions (e.g., “What do you like about tobacco use?” “What is the downside?” “So what kind of roadblocks come to mind when you think about stopping smoking?”) Affirming change talk: This strategy reinforces and focuses on client comments that support stopping tobacco use (e.g., “That’s a good point. Do you have any other concerns?”)

Affirming change talk: This strategy reinforces and focuses on client comments that support stopping tobacco use (e.g., “That’s a good point. Do you have any other concerns?”) Reflective responding: This technique acknowledges to the client “Here is what I heard you say” (e.g., “So one of the most important considerations for you is how your smoking may affect your daughter.”)

Reflective responding: This technique acknowledges to the client “Here is what I heard you say” (e.g., “So one of the most important considerations for you is how your smoking may affect your daughter.”) Summarizing results of the dialogue: This strategy brings closure to the session (e.g., “So if I understand you so far, you enjoy smoking because it relaxes you, but you have some real concern that it is beginning to affect your health and that you may be a negative role model for your daughter. These are all important and valid considerations. With what you have shared with me today, it is clear that you have overcome a number of challenges in your life. I have confidence that you’ll be able to resolve this issue of smoking once you make up your mind. If it is all right with you, I’d like to check in with you at your next dental hygiene appointment to see where you are in your thinking about all of this. Just know that if you decide to try to stop smoking, we can help.”)

Summarizing results of the dialogue: This strategy brings closure to the session (e.g., “So if I understand you so far, you enjoy smoking because it relaxes you, but you have some real concern that it is beginning to affect your health and that you may be a negative role model for your daughter. These are all important and valid considerations. With what you have shared with me today, it is clear that you have overcome a number of challenges in your life. I have confidence that you’ll be able to resolve this issue of smoking once you make up your mind. If it is all right with you, I’d like to check in with you at your next dental hygiene appointment to see where you are in your thinking about all of this. Just know that if you decide to try to stop smoking, we can help.”)Assisting Clients Who Are Ready to Stop Tobacco Use

For clients who state they are ready to quit in the next month, the dental hygienist provides brief assistance with referral for more intensive assistance. Such referral may be either to an internal tobacco cessation program in the dental setting or to an external, community-based tobacco cessation resource (e.g., a telephone quitline, support groups associated with the American Cancer Society, the American Lung Association, or hospitals in the area). A list of community tobacco cessation programs should be developed for use in referral of clients. Once clients choose to stop using tobacco, all dental team members lend support to the tobacco user’s goal of abstinence by providing positive reinforcement and by caring.

The Elicit-Provide-Elicit Model

A recommended model for tobacco cessation assistance with referral is the Elicit-Provide-Elicit model promoted by the Mayo Clinic.7 Using this model, the dental hygienist does the following:

Elicits information to enhance motivation to quit

Elicits information to enhance motivation to quit

Provides:

Provides:

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association Ask, Advise, Refer Model

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA), in partnership with the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center at the University of California, promotes a public health action plan for dental hygienists that simplifies tobacco cessation to a three-step process. The three-step process promotes asking about tobacco use at every visit, advising those who use tobacco to quit, and referring tobacco users to a state or national tobacco quitline by distributing a card with a national number: 1-800-QUITNOW. This model addresses time constraints expressed by dental hygienists related to tobacco cessation counseling. To enhance understanding of the Ask, Advise, Refer (AAR) tobacco cessation model, the ADHA has developed a website (www.askadviserefer.org) with resources to download to use for chairside communications.

Statewide Tobacco Use Quit Lines

Excellent external resources for referral for tobacco cessation assistance are tobacco use telephone quitlines in 42 states in the United States. They offer easy access at no cost to the client and address ethnic and geographic disparities. Many tobacco users prefer quitlines to face-to-face programs because telephone counseling is more convenient and provides anonymity. Key factors that increase quitline effectiveness include the use of trained counselors, a proactive format in which staff initiates contact and follow-up, and the combination of the quitline with client self-help materials and approved pharmacotherapy.5

Key Elements of Intensive Tobacco Cessation Treatment Programs

Whether the dental hygienist refers the client to an intensive (i.e., multiple appointment) tobacco cessation treatment program within the dental setting or within the community, key elements shared by high-quality tobacco cessation programs are listed in Box 34-5 and discussed in detail in the following sections.10

Assessment

Initially, the tobacco cessation counselor assesses clients’ motivation to quit, reasons for quitting, previous quit attempts, nicotine dependence level, tobacco use patterns in a typical day (i.e., the number of dips, chews, or cigarettes used per day and associated cravings and mood states), mood disorder history, and pharmacotherapy contraindications. These assessment data are used to tailor client quit plans based on individual needs. The following information relates to this assessment process.

Motivation to Quit

Motivation is fundamental to changing behavior. A client’s level of motivation to stop tobacco use is often a good predictor of outcome.9 To enhance clients’ motivation and to measure motivation to quit, the counselor reads the following question and asks clients to circle an answer7:

The number circled then serves to measure clients’ initial motivation and to monitor motivation to stop tobacco use at subsequent appointments.7 The number circled also serves as the basis of a discussion to increase clients’ motivation to quit. For example, if a client circles the number 5, the counselor might say, “Great! But why did you circle a 5 rather than a 3?” This open-ended question requires clients to talk positively about their motivation to quit, which serves to enhance their motivation. In general, asking clients why they circled a higher number rather than a lower number on the importance of quitting scale triggers clients to respond positively about their motivation to quit. On the other hand, asking clients why they circled a lower number rather than a higher number requires clients to talk negatively about their motivation to quit, which can become discouraging for them and decrease their motivation to make a quit attempt.

Reasons for Quitting

To enhance motivation to quit, the counselor also asks clients about their reasons for wanting to stop their tobacco use. The counselor may suggest that clients write them down, because motivation may be high initially but may wane somewhat with time. Remembering one’s reasons for quitting enhances motivation and provides incentive to get through tough times during the quitting process. Strong motivation is essential for tobacco users who are trying to quit, and success is unlikely without it.9

Previous Quit Attempts

The counselor assesses clients’ previous experience with quit attempts by asking them if they have tried to quit before and, if so, what problems were encountered.6,7,10 If nicotine replacement or other pharmacologic adjuncts were used, it is important to find out what happened. When discussing quit attempts, the counselor promotes client positive self-image by reminding clients that “Quitting tobacco is a process that takes most people several tries before they are able to quit for good, but most people who persist eventually do quit.”10

Nicotine Dependence

There are many ways to assess nicotine dependence. Recommended evidence-based questions to ask clients are as follows:

Clients who respond “yes” to any of these questions, especially with regard to using tobacco within 30 minutes of waking, are determined to be nicotine-dependent.6

Nicotine dependence also can be assessed by asking the question, “When you smoke, how many cigarettes per day do you usually have?” Clients who report they smoke one to 15 cigarettes per day are considered to be nicotine-dependent lighter smokers, compared with those who report they smoke more than 15 cigarettes per day. To minimize discomfort from nicotine withdrawal, it is important for nicotine-dependent tobacco users to wean themselves off of nicotine before the quit date rather than to stop abruptly (i.e., “cold turkey”). Strategies that combine behavioral and FDA-approved adjunctive pharmacologic support achieve the best outcomes for nicotine-dependent clients.2,5

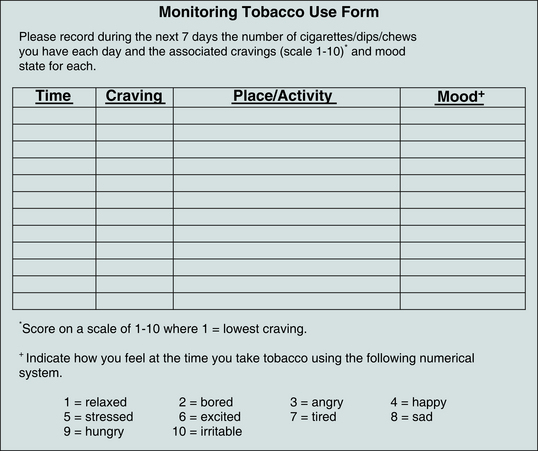

Patterns of Tobacco Use

To assess patterns of use in a typical day, clients are asked to recall each cigarette, chew, or dip they have in a typical day.6 Focusing on a typical day, the counselor helps the client fill out the form shown in Figure 34-7. Beginning with the first dip, chew, or cigarette of the day, the time of day tobacco usually is used and the situation in which the use occurs are recorded.6 Clients are then asked to do the following:

Rate their desire or craving for each recorded tobacco use on a scale of 1 to 10, where a score of 1 represents “do not crave it at all” (the lowest craving) and a score of 10 indicates “have to have it” (the strongest craving). The tobacco uses with lower craving scores are the easiest to eliminate, and it is recommended that clients give them up first in the weaning process.

Rate their desire or craving for each recorded tobacco use on a scale of 1 to 10, where a score of 1 represents “do not crave it at all” (the lowest craving) and a score of 10 indicates “have to have it” (the strongest craving). The tobacco uses with lower craving scores are the easiest to eliminate, and it is recommended that clients give them up first in the weaning process. Describe their mood at each recorded tobacco use by indicating a number between 1 and 10, where 1 = relaxed; 2 = bored; 3 = angry; 4 = happy; 5 = stressed; 6 = excited; 7 = tired; 8 = sad; 9 = hungry; and 10 = irritable.

Describe their mood at each recorded tobacco use by indicating a number between 1 and 10, where 1 = relaxed; 2 = bored; 3 = angry; 4 = happy; 5 = stressed; 6 = excited; 7 = tired; 8 = sad; 9 = hungry; and 10 = irritable.

Figure 34-7 Diary monitoring patterns of tobacco use.

(From Jensen J, Hatsukami D: Tough enough to quit using snuff: a self-help manual for quitting spit tobacco, Minneapolis, 1994, University of Minnesota Tobacco Research Laboratory.)

Understanding the level of craving and the client’s mood when tobacco is used helps to establish a quit plan and to identify coping strategies to prevent relapse once the client quits. After working with the client to monitor tobacco use in a typical day, the counselor may say something like,

“To help you to prepare for quitting, I would like you to continue to monitor your tobacco use over the next week. To accomplish this, I will give you a diary to assess the number of cigarettes you have each day during the next week, the time of day you smoke, the intensity of cravings you have for each cigarette, the place where you are when you use your tobacco, the activity you are doing at the time, and your associated mood state. I would like you to complete the diary I am going to give you and bring it to your next appointment so we can review it together. The craving scores will help us understand which cigarettes might be the easiest to give up first. The mood scores will help us to understand why you use, and that knowledge will help identify ways to help you cope with not using (e.g., if you smoke to relieve stress, then we need to find other ways for you to manage your stress so you won’t need to use tobacco for that purpose).”10

History of Mood Disorders

Because nicotine is a mood elevator, some clients may be using tobacco to self-medicate for depression or anxiety. If this is the case, then there is the potential that stopping tobacco use abruptly may trigger the mood disorder. To assess history of mood disorder, clients are asked if they have ever been treated for depression or anxiety. Clients who have a history of a mood disorder are asked how they currently manage their negative moods. After determining their coping strategies, the client’s physician is contacted to determine the best way to manage the mood disorder during and after the tobacco cessation process.10

Contraindications to Pharmacotherapy

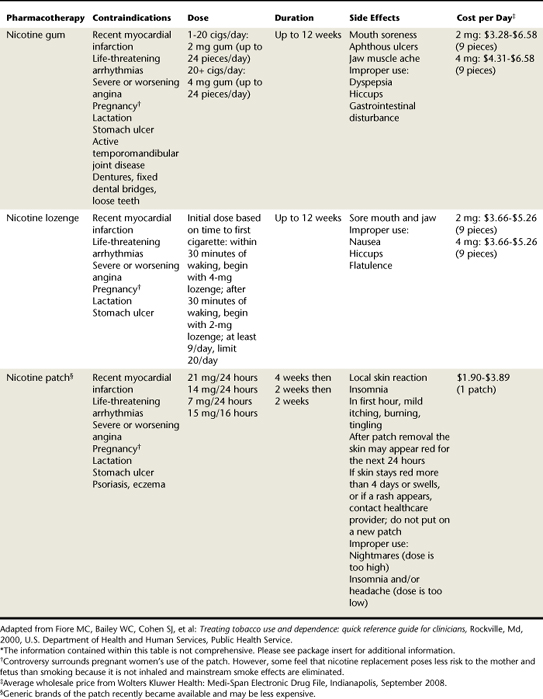

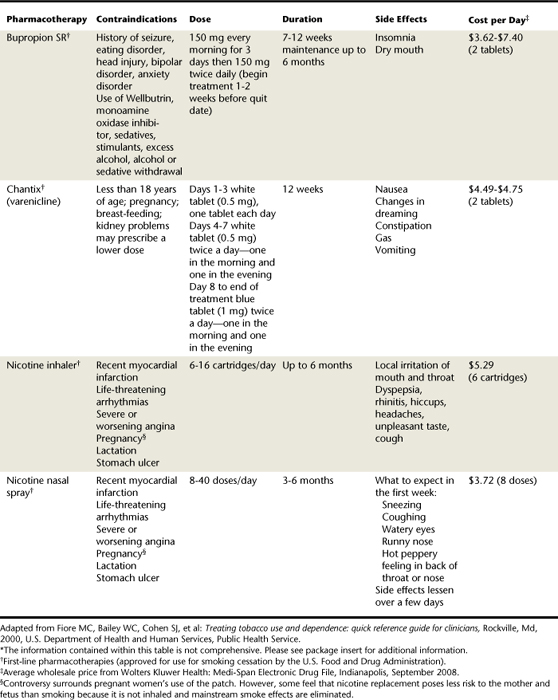

Clinical practice guidelines for treating tobacco use and dependence state, “All patients attempting to quit should be encouraged to use effective pharmacotherapies for cessation except in the presence of special circumstances.” To identify special circumstances that would contraindicate certain types of pharmacologic agents approved for smoking cessation, the cessation counselor assesses the presence of any contraindications to FDA-approved medications. Tables 34-8 and 34-9 list contraindications for specific pharmacologic agents.

Setting a Quit Date

Counselors encourage clients to set a quit date 2 to 4 weeks from the time they decide to quit.5 Then between the time clients decide to quit and their quit date, they can get ready to quit. There is no “ideal” time to quit, but some times are better than others. Low-stress times are best, such as a day when there are no work deadlines. Some clients will select a date of particular significance to them, such as a birthday, anniversary, or new car purchase. On the quit date, total abstinence is essential. The goal is “Not even a single puff or dip after the quit date.”

Choosing a Method

Once a quit date is set, the counselor helps clients establish a method to get ready to quit and to cope with the quitting process. The two basic methods of quitting tobacco use are cold turkey and gradual nicotine reduction. Cold turkey is the approach of quitting tobacco use abruptly on one’s quit date (Box 34-6).5 Gradual nicotine reduction is the approach that slowly and systematically reduces the amount of nicotine clients use so that they will have fewer symptoms of withdrawal on their quit date. Nicotine reduction can be accomplished either by brand switching or by gradually tapering down use of the original brand.6

Brand switching involves changing to another brand of tobacco with a lower level of available nicotine to gradually reduce exposure to nicotine. For example, Table 34-1 lists some brands of spit tobacco according to level of bioavailable nicotine. The counselor emphasizes to clients that if they switch to a brand of tobacco with a lower nicotine content, they must be careful not to increase the amount of tobacco they use in an effort to maintain the same level of nicotine.6

Tapering down use is a method of systematically reducing the number of tobacco uses by a set amount, such as one to two every few days; tapering may also be accomplished with nontobacco oral substitutes. When clients get to the point where they are using half of their original amount of tobacco, they can try to quit cold turkey. For clients who choose to taper down their tobacco use, the counselor refers to their pattern of use in a “typical day” diary collected during the assessment phase of counseling. Based on the diary information, the counselor suggests that clients start cutting back on those cigarettes or dips with the lowest craving scores.6 Table 34-6 lists some helpful suggestions for behavioral strategies to cope with nicotine withdrawal and the temptation to use tobacco. Specific coping strategies clients decide to use and the rewards they plan for themselves on their quit day and for the first week are recorded in the client record.

Coping Skills Training

Coping skills training involves assisting clients to identify action responses (things they can do) and thinking responses (things they can say to themselves) to avoid tobacco use6 when tempted (Box 34-7).

BOX 34-7 Strategies to Cope with Cravings and Temptation to Use Tobacco

From Jensen J, Hatsukami D: Tough enough to quit using snuff: a self-help manual for quitting spit tobacco, Minneapolis, 1994, University of Minnesota Tobacco Research Laboratory.

Action Responses

The following strategies are suggested action responses to cope with temptation to use tobacco.6

Avoidance

During the first 2 weeks of being tobacco-free, many clients avoid situations where their potential for using tobacco is high, such as socializing with other tobacco users. During these high-risk situations (situations where the potential for tobacco use is high), craving and temptation may be strong and motivation to stop using tobacco may waiver.

Distraction

Because a craving disappears in 3 to 5 minutes whether the client uses tobacco or not, teaching clients to focus their attention on doing something else can help them to cope with cravings. For example, when a craving arises, clients could have a glass of water, do a crossword puzzle, doodle, call a friend, brush their teeth, take a walk, or do any number of other activities.

Use of Oral Substitutes

The counselor helps clients make a list of nontobacco oral substitutes for use when they have a strong craving to use tobacco. Clients are counseled to stock up on these substitutes in advance and to put them where they normally keep their tobacco. Examples of nontobacco substitutes include sugarless chewing gum, sunflower seeds in the shell, popcorn, fruits, raw vegetables, flavored toothpicks, hard candy, and herbal substitutes. Clients are instructed to throw out all tobacco and stock up on nontobacco substitutes the night before they quit.6

On Quit Date

Clients are encouraged to change their daily routine on the quit date to break away from tobacco triggers and to decrease temptation to use tobacco (e.g., get right up from the table after meals). It is important for clients to make plans to keep busy. For example, aerobic exercise helps clients to relax and boosts energy and stamina. Also, a dental hygiene care appointment is a good action strategy that promotes health and provides a fresh clean feeling in the mouth.

Thinking Responses

Thinking responses are the client’s thoughts about quitting tobacco use.6 Some thinking responses the client can use to cope with temptation to use tobacco are listed in the following paragraphs.

Positive Thinking

Counselors encourage clients to be as supportive of themselves as they would be to their best friend. It is important for clients to tell themselves, “I will succeed.” When a negative thought or self-doubt comes to mind (e.g., “I can’t do this”), counselors instruct clients to substitute a positive thought such as, “I know it’s difficult, but I can do this, and I will. I just need to get through today or the next hour.” Also, clients need to be encouraged to think in terms of “getting rid of an addiction” rather than “giving up cigarettes or dip.”

Delay

If clients can delay satisfying their craving, it will go away in 3 to 5 minutes. Therefore counselors encourage clients to tell themselves, “I won’t have a cigarette now, I’ll decide again in an hour.” In the meantime, if clients find something else to do to get their mind off the craving, by the time an hour passes they may have forgotten all about it.

Rewards

Helping clients to plan a reward system for attempting to stop their tobacco use is another important strategy. Rewards are important to the quitting process because they help avoid the feeling of deprivation while quitting tobacco. Clients are encouraged to choose rewards for themselves every day for the first week they are tobacco-free and to reward themselves on anniversaries. For example, they could buy a new CD, get a magazine, or go to a movie with a friend. With the money they save from buying tobacco, they could plan to buy something for themselves that they really want. Rewards also can be free, such as sleeping late on the weekend or getting a massage from a friend.

Support from Others

Clients are encouraged to tell family, friends, and co-workers about trying to quit tobacco use and to request their understanding and support.5,6 Stopping tobacco use requires a great deal of effort and energy. Having the support of others is very important. If clients trying to quit are feeling irritable, spouses or partners, family, and friends will be more understanding if they are informed. They can help by not offering tobacco, by giving a pat on the back to reinforce when clients are refraining from tobacco use, and by giving encouragement if things are not going well.

Relapse Prevention

Although nicotine withdrawal lasts only 2 to 4 weeks, the temptation to use can last for years. In order to prevent relapse, it is critical for clients to identify at least three tough situations where they know they will be tempted most to use tobacco, and then to plan ahead to what they will do instead to remain tobacco-free. Planning for these high-risk situations helps clients to out-think their tobacco habit and avoid relapse.6 In addition, because drinking alcohol is highly associated with relapse, counselors often encourage clients to review their alcohol use and consider limiting their alcohol consumption or abstaining from alcohol during the quit process.

Follow-up Contact

Follow-up contact is arranged and scheduled either in person or via telephone. Initial follow-up occurs on the quit date, during the first week after the quit date, and within the first month of the quit date. Additional follow-up contacts are scheduled as needed. During follow-up, the counselor congratulates the client on success. For clients who have experienced a slip (use of tobacco but not a resumption of regular tobacco use), it is important to transform the event into a learning situation. For example, clients may have learned that they really cannot be around friends who smoke or that they need to focus on nontobacco stress reduction techniques. The cessation counselor helps clients identify what caused the slip or relapse and what they can do to prevent a recurrence. If a full relapse has occurred, a new quit date needs to be set. Ongoing support is critical, and for some clients seeking cessation assistance in the dental setting, referral to a more specialized intensive tobacco cessation program may be appropriate.5,10

U.S. FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION–APPROVED PHARMACOLOGIC ADJUNCTS

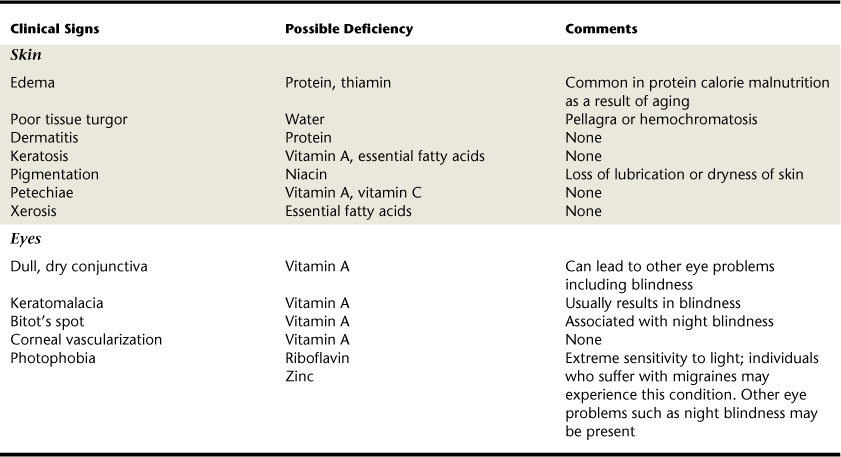

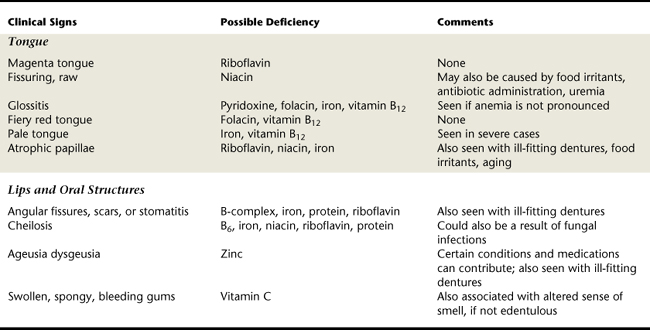

Nicotine-dependent clients usually need pharmacologic support to facilitate their quitting process.2,5 The extent of support the client needs, whether behavioral and/or pharmacologic, drives the tobacco cessation care plan. Although prescribing pharmacologic adjuncts is the dentist’s legal responsibility, the dental hygienist may recommend over-the-counter (OTC) nicotine replacement therapies and other prescription FDA-approved adjuncts. Clients often ask for advice about particular products. The different types of FDA-approved OTC nicotine replacement therapies for smoking cessation are shown in Figure 34-8, and their use and related contraindications and side effects are summarized in Table 34-8. Figure 34-9 shows the FDA-approved nicotine and non-nicotine prescription pharmacologic therapies for smoking cessation, and Table 34-9 summarizes use and related contraindications and side effects. Clients need to be cautioned that no pharmacologic adjunct is a magic bullet. Such adjuncts are helpful in diminishing craving and other withdrawal symptoms, which allows clients to concentrate on action and thinking coping strategies to resist the temptation to use.

Figure 34-8 U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapies for smoking cessation. A, Nicotine gum. B, Nicotine lozenge. C, Transdermal nicotine patch.

Figure 34-9 U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved nicotine and non-nicotine prescription pharmacologic therapies for smoking cessation. A, Nicotine nasal spray. B, Nicotine oral inhaler. C, Bupropion (Zyban). D, Varenicline (Chantix).

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

The purpose of nicotine replacement therapy is to provide some blood concentration of nicotine to reduce or eliminate withdrawal symptoms so clients can focus on psychosocial and behavioral changes necessary to stop their tobacco use.5,10 There may be, however, a period of trial and error to determine the optimum dose of nicotine replacement to avoid nicotine withdrawal symptoms and at the same time avoid nicotine toxicity (nicotine overdose). Nicotine replacement products must be used according to manufacturers’ instructions. Clients must discontinue all tobacco use before starting nicotine replacement therapy to prevent nicotine toxicity, which can cause serious adverse health effects (Box 34-8).

BOX 34-8 Management of Nicotine Toxicity (Overdose)

| Signs and Symptoms of Overdose | Management |

|---|---|

|

If client is using tobacco with nicotine replacement, tell client to discontinue either the use of tobacco or the use of the nicotine replacement product.

|

Current OTC nicotine replacement products are the nicotine transdermal patch system, nicotine polacrilex gum, and the nicotine lozenge (see Figure 34-8). Prescription products available are the nicotine nasal spray and the nicotine oral inhaler (see Figure 34-9). All types of nicotine replacement enhance abstinence when used properly and in conjunction with cognitive-behavioral counseling.2 Choice of modality depends on client history, contraindications, preference, and/or provider experience with a given product. In general, nicotine replacement products are contraindicated for clients with underlying cardiovascular disease, especially those who have had a recent myocardial infarction, life-threatening arrhythmias, or severe or worsening angina. Other contraindications related to specific products are listed in Tables 34-8 and 34-9. Nicotine toxicity also can result if clients overuse nicotine replacement products. See Box 34-8 for symptoms and management of nicotine toxicity.6

Transdermal Nicotine Replacement Therapy (Patch)

Transdermal nicotine patches are marketed for 24-hour usage. An advantage of the patch is that it delivers a constant dose of nicotine across the skin throughout its use. A small percentage of clients using the 24-hour patch have reported sleep interrupted by nightmares, an indication of nicotine toxicity. If this occurs, the dose of nicotine should be reduced either by removing the patch during sleeping hours or by using a lower-dose patch. Clients also may experience dermatitis as a side effect of using the patch (see Table 34-8). Directions for use require the client to place a new patch each day on a nonhairy site of the upper trunk. No one site should be used again in less than a week. Used patches should be disposed of carefully, because residual nicotine could harm small children and animals. Patches work on a dosing-down principle, and the aim is to gradually discontinue use over 12 weeks (e.g., 21 mg for weeks 1 to 8; 14 mg for weeks 8 to 10; and 7 mg for weeks 10 to 12). The client eventually is weaned off nicotine. Each patch dose is generally of a 2- to 4-week duration, depending on client response. Small-framed or obese clients may require dose modification. Triage with the client’s physician is advised, particularly if the client has systemic disease. In general, client compliance is easier to achieve with the patch than with other forms of nicotine replacement that require more behavior modification. Once the patch is placed, a client needs to do no more until the next day.10

Nicotine Polacrilex (Gum)

Nicotine gum is available OTC in 2- or 4-mg doses. Dose is based on smoking pattern. For clients who smoke less than 25 cigarettes per day, 2-mg gum is recommended. For those smoking more than 25 cigarettes per day, 4-mg gum is recommended. The aim is to discontinue gum use gradually over 10 to 12 weeks. The recommended schedule is one piece of gum every 1 to 2 hours per day for weeks 1 to 6; one piece of gum every 2 to 4 hours for weeks 7 to 9; and one piece of gum every 4 to 8 hours for weeks 10 to 12. Proper gum use requires clients to chew the gum very slowly because the nicotine is absorbed through the oral mucosa (in an alkaline environment) and not the gut (an acidic environment). The client should stop chewing at the first sign of a peppery, minty, or citrus taste or tingle and then “park” the gum between the cheek and the gingiva. Overchewing can result in nicotine toxicity, in which the client may experience stomach upset, nausea, and/or vomiting. Success with nicotine gum is greater when the client has a fixed dosage schedule throughout the day to prevent craving. Often if clients wait until a craving arises before using a piece of gum, they will relapse to tobacco use, because a cigarette or dip provides more rapid absorption of nicotine into the blood compared with the gum. To avoid withdrawal and relapse, nicotine gum is sometimes used in the morning in combination with the patch when the patch is first placed. This action enables the client to receive a quick boost of nicotine with the addition of the gum to prevent breakthrough craving (see combination therapy below). The nicotine patch provides nicotine to the bloodstream at a constant rate and dosage. (See Table 34-8 for contraindications and side effects.)

Nicotine Lozenge

The nicotine lozenge is available OTC in 2- or 4-mg doses. The lozenge provides 25% more nicotine than the equivalent nicotine gum dose because the lozenge dissolves in the mouth completely in 20 to 30 minutes. Like the gum, it is used on a regular schedule (every 1 to 2 hours) throughout the day to prevent cravings. The initial dose is based on the time of first cigarette use after waking. Those who have a history of having their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking begin with the 4-mg lozenge. The aim is to discontinue use gradually over 12 weeks on a schedule similar to that used for the gum. The lozenge is meant to be parked next to the oral mucosa. The client should not chew or swallow the lozenge for maximum effectiveness and to avoid adverse side effects similar to those reported for improper use of the gum. (See Table 34-8 for contraindications and side effects.)5

Nicotine Spray

The nicotine nasal spray is available by prescription only owing to the rapid absorption of its nicotine through the nasal membranes into the blood and therefore its potential for abuse. Of all of the nicotine replacement products the nicotine spray provides the fastest nicotine delivery system (i.e., nicotine is absorbed into the blood the fastest). Each dose spray is metered to deliver 0.5 mg of nicotine in each nostril. It is used on a daily fixed schedule beginning with one or two doses per hour. For best results, at least eight doses are recommended daily for the first 6 to 8 weeks. Dosage should never exceed five doses in 1 hour or 40 doses in 24 hours. The aim is to gradually discontinue use over an additional 4 to 6 weeks. (See Table 34-9 for contraindications and side effects.)

Nicotine Oral Inhaler

The nicotine oral inhaler is available by prescription only (see Figure 34-9). It consists of a mouthpiece and plastic cartridge delivering 4 mg of nicotine vapor. The client inhales into the back of the throat by puffing in short breaths. The nicotine is absorbed across the oropharyngeal mucosa. In general, the use of 6 to 16 cartridges per day for 3 to 12 weeks is recommended, however, use depends on clients’ individual smoking history. The inhaler is most effective if puffed frequently for 20 minutes at a time. The aim is to discontinue use gradually over an additional 6 to 12 weeks. (See Table 34-9 for contraindications and side effects.)

Combination Nicotine Replacement Therapy

The nicotine patch is a long-acting formulation that produces relatively constant levels of nicotine. Short-acting, rapidly absorbed formulations such as the nicotine gum, lozenge, inhaler, and spray are often used to augment the patch to prevent or control breakthrough cravings or withdrawal symptoms. These short-acting formulations (gum, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray) allow for acute dose titration as needed in severely nicotine-dependent tobacco users trying to stop their tobacco use.5,10

Sustained-Release Bupropion (Zyban)

Some tobacco users achieve successful abstinence from tobacco by using sustained-release bupropion, a non-nicotine prescription antidepressant drug (see Figure 34-9). Bupropion increases levels of dopamine and norepinephrine released from the brain. Clients can continue their tobacco use for 7 to 14 days once they start the medication. Initially, clients take one tablet (150 mg) in the morning for 3 days. If the drug is tolerated, the dosage is increased to two tablets per day 8 hours apart (300 mg per day) for 7 to 8 weeks. History of head injury, seizure disorder, eating disorder, and/or use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the past 14 days contraindicates use of bupropion. (See Table 34-9 for other contraindications and side effects.)

Varenicline (Chantix)

Varenicline, a prescription drug, binds to nicotine receptors to block the neurochemical effects of nicotine (see Figure 34-9). Clients can continue their tobacco use for 7 days after they start the medication. Initially, clients take one white tablet (0.5 mg) in the morning for 3 days. If the drug is tolerated, the dose is increased to two tablets per day 8 hours apart (1 mg per day) for days 4 to 7. At the end of the first week, clients quit their tobacco use. From day 8 up to 12 weeks, clients take one blue tablet (1.0 mg) twice a day with 8 ounces of water after eating. (See Table 34-9 for contraindications and side effects.)

NEW ADVANCES IN RESEARCH

Nicotine Vaccine

The purpose of a nicotine vaccine is to raise antibodies against the nicotine molecule. A nicotine vaccine is under research with promising results in animal and human trials. Studies have found 16% to 42% of individuals able to quit after 12 months in groups with the highest antibody response. Several companies are developing the vaccine, and the expected launch year is 2010-2012. The benefit of the nicotine vaccine is it does not act on the central nervous system. Instead, antibodies from the vaccine bind to the nicotine in the blood, preventing it from reaching the brain and having an affect on the brain’s dopamine reward system.11

NicoTest

The NicoTest, available in England, analyzes two genes, DRD2 and CYP2A6. The DRD2 gene helps to regulate cell receptivity to dopamine. The CYP2A6 gene influences how quickly tobacco users metabolize nicotine and clear it from the body. In England, physicians use the NicoTest to determine whether an individual goes on nicotine replacement medications or Zyban to assist with the tobacco cessation process.11

IMPLEMENTING A TOBACCO INTERVENTION PROGRAM IN THE ORAL HEALTHCARE SETTING7

Dental hygienists often are the strongest proponents of tobacco intervention activities in their employment settings. Four key steps are necessary to ensure successful incorporation of tobacco intervention programs into clinical settings: generating team support, designating a coordinator, creating a tobacco-free environment, and addressing reimbursement issues (Box 34-9).

BOX 34-9 Key Steps to Implementing Tobacco Intervention Programs

DENTAL HYGIENIST’S ROLE IN THE COMMUNITY

The dental hygienist’s role related to tobacco extends beyond the immediate clinical environment.8 Given its magnitude as a public health issue, tobacco use commands dental hygienists’ action at the professional and societal levels. Ethically, dental hygienists are committed to the health and well-being of society. Involvement with tobacco-related issues helps achieve that goal. Professional and societal activities that dental hygienists can pursue within their professional associations and communities include the following:

Endorse tobacco intervention policies within local, state, national, and international associations.

Endorse tobacco intervention policies within local, state, national, and international associations. Ensure that continuing education related to tobacco issues is on the agenda for professional conferences.

Ensure that continuing education related to tobacco issues is on the agenda for professional conferences. Provide tobacco use education to children, sports teams, parent-teacher associations (PTAs), and other relevant community groups.

Provide tobacco use education to children, sports teams, parent-teacher associations (PTAs), and other relevant community groups.CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Inform that most tobacco users who successfully quit establish a quit date, a date 2 to 4 weeks from the time they decide to quit. Then between the time they decide to quit and their quit date they get ready to quit.

Inform that most tobacco users who successfully quit establish a quit date, a date 2 to 4 weeks from the time they decide to quit. Then between the time they decide to quit and their quit date they get ready to quit.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

As oral healthcare providers, dental hygienists are ethically obligated to address clients’ tobacco use and its relationship to their oral health and overall well-being.

As oral healthcare providers, dental hygienists are ethically obligated to address clients’ tobacco use and its relationship to their oral health and overall well-being. Because tobacco use is a life-threatening habit, all tobacco-using clients must be informed of its deleterious effects and educated and guided toward abstinence.

Because tobacco use is a life-threatening habit, all tobacco-using clients must be informed of its deleterious effects and educated and guided toward abstinence.KEY CONCEPTS

Nicotine addiction is a physical, psychologic, behavioral, and sensory dependence that makes it very difficult for one to stop tobacco use.

Nicotine addiction is a physical, psychologic, behavioral, and sensory dependence that makes it very difficult for one to stop tobacco use. The Five A’s approach, an evidence-based approach to brief, effective tobacco cessation intervention, is a methodology endorsed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Cancer Institute for implementation by oral health and medical care teams in private practice and community settings.

The Five A’s approach, an evidence-based approach to brief, effective tobacco cessation intervention, is a methodology endorsed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Cancer Institute for implementation by oral health and medical care teams in private practice and community settings. The Five A’s approach requires healthcare providers to ask all clients about tobacco use; advise tobacco users to quit, showing them the visible effects of tobacco use in their own mouths; assess their readiness to quit; assist with the quitting process; and arrange follow-up on their cessation progress.

The Five A’s approach requires healthcare providers to ask all clients about tobacco use; advise tobacco users to quit, showing them the visible effects of tobacco use in their own mouths; assess their readiness to quit; assist with the quitting process; and arrange follow-up on their cessation progress. Stages of readiness to change are progressive levels of mental readiness through which clients pass as they work to stop their tobacco use.

Stages of readiness to change are progressive levels of mental readiness through which clients pass as they work to stop their tobacco use. The type of assistance provided to promote tobacco cessation is determined by the client’s readiness to quit.

The type of assistance provided to promote tobacco cessation is determined by the client’s readiness to quit. Characteristics of patient-centered communication are collaboration, not persuasion; elicitation of information, not imparting information; and emphasis on client autonomy, not the authority of the expert.

Characteristics of patient-centered communication are collaboration, not persuasion; elicitation of information, not imparting information; and emphasis on client autonomy, not the authority of the expert. The motivational interview is a form of patient-centered communication to help clients get unstuck from the ambivalence that traps them in their tobacco use.

The motivational interview is a form of patient-centered communication to help clients get unstuck from the ambivalence that traps them in their tobacco use. Once the benefits of quitting tobacco use outweigh the benefits of continuing tobacco use, a client will make a decision to quit.

Once the benefits of quitting tobacco use outweigh the benefits of continuing tobacco use, a client will make a decision to quit. Motivation is fundamental to changing behavior. Asking clients why they circled a higher number rather than a lower number on a 1-to-10 scale rating importance of reasons to quit (where 10 indicates the highest motivation) requires clients to talk positively about their motivation to quit and serves to enhance their motivation.

Motivation is fundamental to changing behavior. Asking clients why they circled a higher number rather than a lower number on a 1-to-10 scale rating importance of reasons to quit (where 10 indicates the highest motivation) requires clients to talk positively about their motivation to quit and serves to enhance their motivation.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

SCENARIO 1

Profile: A 45-year-old white male visits the dental hygiene clinic. He has been dipping snuff for 18 years. He drinks approximately three beers per day.

Chief Complaint: “My tooth hurts on the upper left back.”

Dental History: Client erratically seeks care. He has not seen a dentist or dental hygienist in over 5 years.

Social History: The client is divorced and lives alone. He frequently travels abroad for business reasons. He is a full-time employee for a computer company.

Health History: Client reports no use of medications. He broke his arm in a skiing accident 2 years ago. He reports no systemic disease.

Oral Health Behaviors Assessment: The client reports brushing one time per day with a hard brush. He does not rinse or floss. He uses no aids.

Supplemental Notes: On clinical examination, a 10- × 20-mm mixed leukoplakic and erythroplakic lesion is found on the vestibular right labial mucosa of the maxilla, extending to the surrounding alveolar mucosa and attached gingiva. The client places his oral snuff in that area. He was unaware of the lesion, and the lesion was asymptomatic.

SCENARIO 2

Profile: A 35-year-old female visits for a 3-month recall appointment. The client reports smoking three packs of cigarettes per day.

Chief Complaint: “I am unhappy about the stains on my front teeth and the color of my fillings on my front teeth.”

Dental History: Client makes regular dental visits although she is 9 months overdue for her dental hygiene visit. She consistently has reported interest in tobacco cessation but has rejected the use of nicotine replacement. She states, “I want to do it on my own.”

Social History: Client has been smoking for 25 years. She drinks six to eight cups of coffee per day. She is a recovering alcoholic. She is unmarried and lives with her father. Ms. J is weight conscious.

Health History: Past history of depression. Ibuprofen as needed for back pain from an injury sustained 10 years ago.

Oral Health Behaviors Assessment: The client reports brushing three times per day with a power toothbrush, flossing one time per day, and using a mouth rinse several times per day. She rarely exercises.

Supplemental Notes: Client has thick, heavy black stains, generalized. She reports presence of xerostomia.

1. National Cancer Institute. Tobacco research implementation plan: priorities for tobacco research beyond year 2000. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; 1998.

2. Fiore M.C., Bailey W.C., Cohen S.J., et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: clinical practice guideline. Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: what it means to you. Bethesda, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 2004.

4. American Academy of Periodontology, Research, Science and Therapy Committee: Position paper: tobacco use and the periodontal patient. Available at: www.perio.org/practitioner/tobacco.htm. Accessed November 15, 2007.

5. Walsh M.M., Ellison J. Treatment of tobacco use and dependence: the role of the dental professional. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:521.

6. Jensen J., Hatsukami D. Tough enough to quit using snuff: a self-help manual for quitting spit tobacco. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Tobacco Research Laboratory; 1994.

7. Mayo Clinic University of Minnesota: Stop smoking services. Available at: www.mayoclinic.org/stop-smoking. Accessed November 15, 2007.

8. Prochaska J.O., Norcross J.C., DiClemente C.C. Changing for good: the revolutionary program that explains the six stages of change and teaches you how to free yourself from bad habits. New York: William Morrow; 1994.

9. Miller W., Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. Guilford Press; 2002.

10. Walsh M.M., Heckman B., Murray J., Kavanagh C. UCSF School of Dentistry translating clinical guidelines for treating tobacco use and dependence. San Francisco: University of California–San Francisco; 2006.

11. Shine B: Nicotine vaccine moves toward clinical trials. http://www.nida.nih.gov/nida_notes/NNVol15N5/Vaccine.html. Accessed August 24, 2008.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..