CHAPTER 44 Oral Care of Persons with Cancer

Today, clients in need of oral care are living longer and may very well have survived, or may be coping with, a life-threatening disease such as cancer. The dental hygienist will need to understand the oral, physical, and psychologic issues surrounding a client currently battling or having survived cancer. Cancer is not a single disease but a broad classification of more than 100 types of diseases. The common element in cancer is the abnormal and unrestricted growth of cells that can invade and destroy surrounding normal body tissues, sometimes spreading to other parts of the body. The difference between a malignant and a benign neoplasm is that a benign tumor is usually circumscribed and encapsulated, usually grows slowly, and is composed of cells that resemble the tissue from which it arises. A malignant neoplasm or cancer not only infiltrates locally but also has the potential to metastasize or spread to distant sites. The cells are usually atypical or dysplastic and may not resemble the parent tissue. The branch of medicine that studies and treats cancer is called oncology, and the physician specialist is an oncologist.

CANCER

Incidence

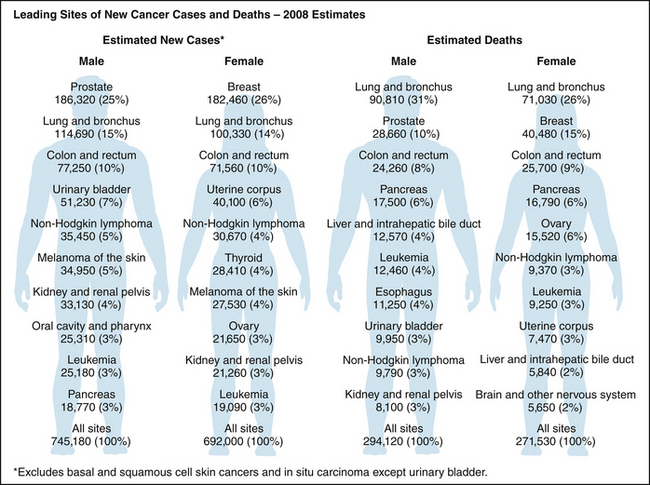

To many, a cancer diagnosis evokes immediate fear of suffering and death. Fortunately there has been a significant decline in cancer deaths in recent years primarily owing to a decrease in tobacco use and an increase in cancer screening, early detection, and effective treatment.1 Figure 44-1 lists the leading types of new cancer cases and deaths according to the American Cancer Society (ACS) 2007 estimates.2 Of the estimated 559,650 deaths annually resulting from cancer, 168,000 deaths are caused by tobacco use; another 184,685 deaths are caused by obesity, poor nutrition, and inactivity; and many of the remaining deaths are caused by infectious agents and sun exposure. Although anyone could potentially develop cancer, approximately 77% of newly diagnosed cancer cases are in people 55 years of age and older. When cancers are left untreated, they result in significant morbidity and death. In the United States, only heart disease causes more deaths in adults.2

Risk Factors

Carcinogenic, or cancer-causing, influences may be environmental, behavioral, viral, or genetic. The National Cancer Institute implicates tobacco use as the single major cause of preventable cancer deaths. Other environmental carcinogenic agents are alcohol, chemicals, radiation, sunlight, hormones, and asbestos. Behavioral factors that could lead to the development of cancer include smoking, alcohol abuse, overweight or obese condition, poor nutrition, and inactivity. There is also evidence that certain viruses, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human papillomavirus (HPV), and Helicobacter pylori may be linked to the development of cancers, especially cancers of the liver, nasopharynx, cervix, and lymphatic system.2 Many of these risk factors could be minimized through behavior change as well as the use of vaccines and antibiotics.

Common Signs and Symptoms

In early stages most cancers exhibit no symptoms. Box 44-1 lists the most common presenting signs and symptoms of early cancer, which vary depending on cancer type. Pain is not often a symptom in early stages of cancer. A person who has one of the seven common signs of cancer for longer than 2 weeks should see a doctor promptly.

Oral Cancer Incidence and Risk Factors

In 2008 the ACS estimated that approximately 35,310 new cases (25,310 men and 10,000 women) of oral or pharyngeal cancer, or oral cancer, would be diagnosed.2 Approximately nine of every 10 oral malignancies are squamous cell carcinomas, often manifesting as a painless swelling or lump in the oral cavity or pharynx and larynx area (Box 44-2). The average age of a person with newly diagnosed oral cancer is 62 years.3 Of the newly diagnosed cases, 5210 men and 2380 women were expected to die from these cancers. Fortunately, oral cancer incidence rates have been on the decline for both men and women since 1980.2 The overall 1-year survival rate for all stages of oral cancer is about 84% with a 5-year survival rate of 60%.2 Even though there is a decline in incidence, oral cancer screening remains a very important component of dental hygiene care, as do continued efforts to educate the public about this life-threatening cancer.

Specific oral cancer risk factors include the use of all tobacco products (cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and smokeless tobacco) and alcohol (Box 44-3). Cigarette smokers have an approximately tenfold-increased chance of developing squamous cell carcinoma when compared with people who have never smoked.4 The risk of developing any cancer increases with both amount and duration of tobacco product use. Individuals who smoke and drink alcohol heavily account for approximately 80% to 90% of oral cancer in the United States.

BOX 44-3 Oral Cancer Risk Factors

From American Cancer Society: Cancer facts and figures 2008. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/2008CAFFfinalsecured.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2008.

Recent studies have suggested that the small increase in the number of oral cancers reported in the United States may be related to HPV-16. These cancers are primarily found in the tongue and the oropharyngeal area (throat, back third of tongue, soft palate, side and back walls of the throat, and tonsils) of adults younger than 45 years old.4

The prognosis for a specific oral cancer is highly variable and depends on the stage and location of the disease when it is first diagnosed. National Cancer Institute data collected between the years 2000 and 2004 demonstrated that persons with a small, localized oral squamous cell cancer have an 82% 5-year survival rate, compared with only 27% for a late-stage oral cancer.1 Early detection is the key to survival. The most common intraoral sites for squamous cell cancer are the lateral borders and ventral surfaces of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the oropharynx. Any of the signs and symptoms that persist for longer than 2 weeks after removal of potentially irritating factors and/or application of therapeutic measures must be considered to result from cancer until the condition is proven benign by biopsy (surgical removal of all or part of the lesion) and microscopic evaluation.

CANCER THERAPY

Forms of Cancer Therapy

The choice of cancer treatment is dependent on the type and stage of cancer. Therapy may include one or a combination of the following: chemotherapy, bone marrow and blood transplantation, radiation, surgery, hormone therapy, and immunotherapy. Some cancers respond to a single mode of treatment, whereas others require multimodal treatment strategies. The goal of cancer treatment is to remove or totally destroy the malignant cells from the body. Unfortunately, treatments available today are not able to target only the cancer cells, and normal healthy cells must sometimes be destroyed during the treatments. This may result in significant psychologic stress and physical morbidity or death.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs for the treatment of cancer. Combinations of chemotherapeutic agents have resulted in significant improvement in cure rates for some cancers.

Other cancers are not cured by chemotherapy alone, but the drugs are used in combination with surgery and/or radiation to destroy cancer cells that may have spread systemically. Sometimes chemotherapy is used by itself for a period of time to control a tumor that cannot be eradicated.

The most common overall complication of chemotherapy is infection as a result of myelosuppression (decreased immune response). Oral infections may spread systemically, leading to sepsis and death. Other complications of chemotherapy include electrolyte imbalances, bleeding and hemorrhage, and acute toxicity from the drugs, including nausea and vomiting, photosensitivity, central nervous system dysfunction, alopecia (hair loss), and poor nutritional status. Drugs are available for the control of nausea and vomiting.

Chemotherapy is not only physically demanding but also stress-producing. Persons undergoing cancer therapy need support from family, friends, and caregivers who are good listeners, who allow a full range of emotions, and who encourage hope. Chemotherapy for head and neck cancers, as well as malignancies in other parts of the body, may result in oral complications.

Bone Marrow and Blood Stem Cell Transplantation

Bone marrow and blood stem cell transplantation (BMT) is a therapeutic procedure used to treat a variety of hematologic diseases including aplastic anemia, leukemias, lymphomas, neuroblastoma, and immunodeficiency diseases. BMT is also used to treat some solid tumors.

Bone marrow and blood transplantation begins with the donation of normal bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells. The individual with cancer then goes through a “conditioning phase” in which superlethal doses of chemotherapy and sometimes total body irradiation (TBI) are administered. The goal is to destroy all of the malignant cells and suppress the immune system to permit engraftment of the normal bone marrow. After clients have been conditioned, the marrow or peripheral blood stem cells are intravenously infused into their blood. If engraftment takes place, the cells begin to reproduce new marrow within 2 to 4 weeks.

A significant problem that exists for clients who receive marrow or peripheral blood stem cells from another individual (allogeneic bone marrow transplant) is graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). This disease results from an immunologic reaction wherein the donor cells react against the host tissue antigens. If this occurs within the first 100 days after transplant, it is called acute GVHD and is characterized by dermatitis, enteritis, and hepatitis. If it occurs after the first 100 days, it is termed chronic GVHD and has manifestations similar to those of autoimmune disorders. These may include skin diseases, keratoconjunctivitis, oral mucositis, salivary gland dysfunction or xerostomia, esophageal and vaginal strictures, pulmonary insufficiency, intestinal problems, and chronic liver disease. Both forms of GVHD can result in fatal infections. To prevent GVHD, various types of immunosuppressive therapy are used.

During the first 30 days after transplantation the client experiences cytotoxic and immunosuppressive oral manifestations from the chemoradiotherapy conditioning. These may include severe mucositis, ulceration, hemorrhage, infection, and salivary gland dysfunction. Infections during the first 30 days intensify the mucositis and ulcerations, opening a portal of entry for organisms into the blood.

During the next several months the client's acute manifestations begin to resolve unless GVHD develops. Common complaints with GVHD are xerostomia and mucositis. Also, there may be evidence of lichen planus–like or lupuslike lesions, sometimes becoming erosive. Generalized atrophy of the mucosa and changes consistent with scleroderma may be seen. Viral infections, including herpes simplex virus and fungal infections, are common.

After the first 100 days after transplantation, persons with no evidence of GVHD usually do not have any oral complaints other than varying degrees of xerostomia. Those persons with persistent xerostomia may develop rapid demineralization of the tooth structure and oral infections. Patients who are scheduled for bone marrow or blood transplantation should undergo a thorough oral and dental evaluation and necessary treatment before transplant. All potential sources of infection and irritation should be treated because chronic, asymptomatic oral infections may become acute during immunosuppression and/or GVHD and may lead to sepsis and even death.

Head and Neck Radiation and Surgical Treatment

Both head and neck radiation and surgical treatment for oral cancer have unique client care issues that differ somewhat from chemotherapy and BMT. These specific issues are addressed later in this chapter. The following section reviews oral side effects common to many cancer therapies.

ORAL CONSIDERATIONS OF GENERAL CANCER THERAPY

Oral side effects of cancer treatment that result from unintended disruption and destruction of healthy tissue can be so debilitating that patients may tolerate only lower, less-effective doses of cancer therapy or they may delay or discontinue scheduled treatments. Preventing and managing oral complications helps support optimal cancer treatment and enhances patient survival and quality of life. The National Institutes of Health formally recognize the critical role that dentists and dental hygienists play in the overall care of the individual with cancer.5 Dental hygiene care is critical to the prevention or amelioration of the oral complications associated with all forms of cancer treatment.

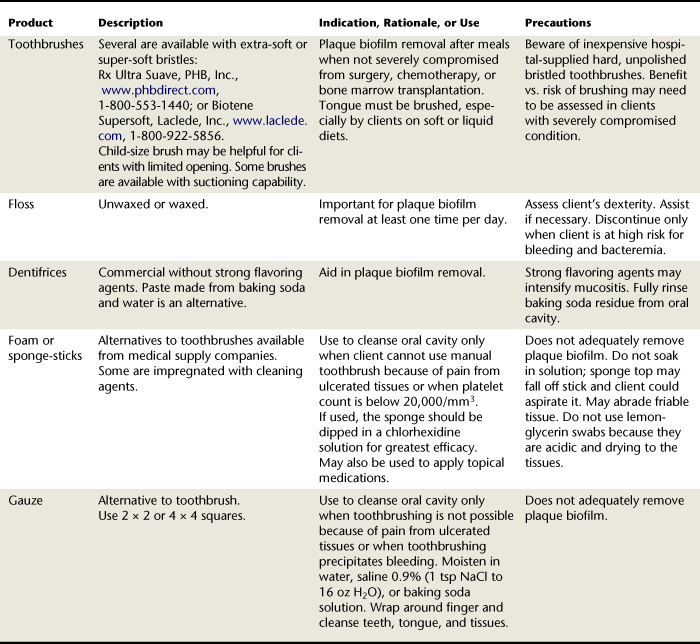

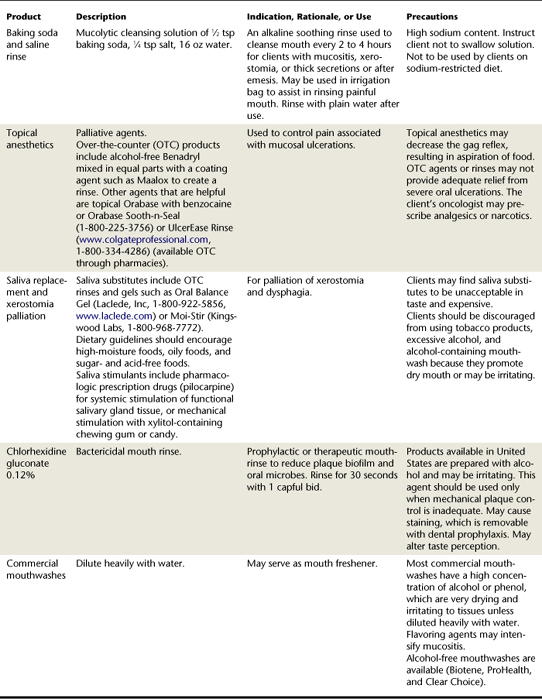

All patients receiving radiation for head and neck malignancies, 80% of bone marrow transplant recipients, and 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy for any malignancy have oral complications. Risk for oral complications varies with the treatment regimen (Box 44-4). Some oral complications occur only during cancer therapy, whereas others, such as xerostomia (dry mouth) and salivary gland dysfunction, may be lifelong in the case of radiation therapy. Before, during, and after radiation and chemotherapy, the dental hygienist plays a key role in helping clients with cancer understand that good oral hygiene care prevents or reduces oral complications, which in turn improves clients’ quality of life and the likelihood that they will be able to tolerate optimal doses of cancer treatment (Box 44-5). For example, the dental hygienist collaborates with the client to establish an oral self-care regimen to protect mouth tissues and to minimize oral complications. To that end the dental hygienist reviews toothbrushing and interdental cleaning techniques and other approaches such as the use of antimicrobial and fluoride mouth rinses and fluoride gel to keep the mouth as moist and clean as possible to reduce risk of dental caries, oral infection, and pain (Table 44-1). The importance of the role of the dental hygienist in enhancing quality of life and potential survival cannot be overemphasized.

BOX 44-4 Risk Levels for Oral Complications

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health: Oral complications of cancer treatment: what the oncology team can do, Publication No. 99-4360, Bethesda, Md, 2008, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

BOX 44-5 Benefits of Good Oral Hygiene Care before and during Cancer Therapy

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health: Oral complications of cancer treatment: what the oncology team can do, Publication No. 99-4360, Bethesda, Md, 2008, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

Oral Complications of Chemotherapy and Bone Marrow and Blood Stem Cell Transplantation

Not all chemotherapy protocols result in oral manifestations, but many have either a direct or indirect effect on the mouth. Oral problems related to myelosuppression may be significantly prevented or diminished through aggressive preventive dental hygiene interventions. The oral manifestations of chemotherapy listed in Box 44-6 and described in the following sections are not permanent, but the client will be at risk for these complications throughout the entire period during which the drugs are being administered.

BOX 44-6 Oral Complications of Chemotherapy

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health: Oral complications of cancer treatment: what the oncology team can do, Publication No. 99-4360, Bethesda, Md, 2008, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

Mucositis

Some chemotherapeutic drugs are toxic to the oral mucosa and cause edema, inflammation, and ulcerations (mucositis) within a few days after the administration of the drug. Ulcerations from chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy are alike in their clinical presentation, with red, swollen tissue that later develops into a yellowish membrane-covered ulcerated tissue (Figure 44-2). If the tissues do not become secondarily infected, the ulcerated tissue will heal within a few weeks of the drug delivery or radiation therapy. Clients with mucositis report burning, pain, and general discomfort, which can interfere with talking, swallowing, and obtaining proper nutrition.

Management

Mucositis may be prevented or lessened in severity by dental hygiene interventions that create a clean and well-hydrated oral environment, good nutritional status, and control of secondary infection (Box 44-7). The client should be encouraged to rinse frequently with sodium bicarbonate and saline water rinses and alcohol-free mouth rinses (see Table 44-1). These rinses soothe and hydrate the inflamed tissues, aid in bacterial plaque biofilm removal, and neutralize pH if the client is vomiting. Pain management begins with mild topical anesthetics and may progress to systemic analgesics and even narcotics.

BOX 44-7 Managing Mouth Pain from Mucositis

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health: Oral complications of cancer treatment: what the oncology team can do, Publication No. 99-4360, Bethesda, Md, 2008, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

Neurotoxicity

Some chemotherapeutic agents derived from plant alkaloids (such as vincristine) are toxic to nerve tissue and may cause severe, deep, and often bilateral odontogenic-like pain known as neurotoxicity. When no dental pathology can be found, the drug may be implicated. The pain subsides within a few days after administration of the drug.

Infection

Some chemotherapeutic agents suppress the bone marrow, resulting in immunosuppression (decreased immune response) and bleeding problems. During these periods the client will be at risk for developing oral infections (fungal, viral, and bacterial) that may increase the risk for a systemic infection, especially if there is a break in mucosal integrity that allows organisms to enter the blood. Oral infections can result in significant morbidity for the client undergoing chemotherapy. Oral infections not only intensify mucositis, but with a breach in the oral mucosa, oral infections may lead to septicemia and death in clients with profound immunosuppression.5 Inappropriately timed dental and dental hygiene procedures can result in bacteremia, causing sepsis and death.

Management

The final decision regarding the safest time to schedule oral healthcare appointments is made by the oncologist. If necessary, the oncologist may recommend antibiotic prophylaxis before dental and dental hygiene care.

A potential rationale for antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment exists when the client has an indwelling central venous catheter for chemotherapy delivery. Some individuals begin chemotherapy without a central venous catheter but have one placed later during therapy. Therefore each time a client is seen it is necessary to ask if a catheter has been placed since the last appointment, because it may become colonized with oral organisms after a dental or dental hygiene procedure. Although no data are currently available to document the absolute need for prophylactic antibiotics in this patient population before dental procedures, the oncologist should be consulted as to what antibiotics may be necessary (see Chapter 10 for a discussion of antibiotic premedication).

Some cancer centers have clients discontinue toothbrushing and flossing during severe myelosuppression. This practice is controversial, however, because there is evidence that toothbrushing and flossing during immunosuppression are not detrimental, and a decrease in plaque biofilm and local infection reduces the risk for potentially life-threatening systemic infection.

Clients with dentures should be evaluated frequently and encouraged to call the dental office whenever necessary to seek early intervention for an oral complication or dental-related sources of pain, irritation, or dental trauma. Oral tissues may change significantly during chemotherapy from edema, inflammation, ulceration, and/or weight loss. Clients should understand that when denture irritation occurs, the prosthesis should be removed from the mouth to avoid further trauma. Persons with oral infections may reinfect their mouths with poorly cleansed dentures. It is important for the client to clean and disinfect the dentures daily and keep them out of the mouth while sleeping. Denture soaking solutions must be changed daily, and the soaking container cleansed and rinsed thoroughly (see Chapter 55).

Hemorrhage

Myelosuppression from chemotherapy may result in thrombocytopenia, reduction of clotting factors. Clients with platelet counts under 50,000/mm may experience oral hemorrhaging (bleeding) during invasive dental and dental hygiene procedures.5 The occurrence of spontaneous gingival bleeding increases with a platelet count below 20,000/mm.5 When there is a disruption of the mucosal integrity and/or periodontal disease, clients are at greater risk for bleeding. This fact emphasizes the need for early debridement and periodontal maintenance care.

Management

When scheduling a client undergoing chemotherapy for a dental hygiene appointment, it is imperative to consult the oncologist regarding the status of the client's blood counts and clotting factors to avoid potential bleeding problems associated with chemotherapy. Generally, a platelet count of at least 50,000/mm is recommended before invasive dental or dental hygiene procedures.5 If a dental or dental hygiene procedure is absolutely necessary during periods of thrombocytopenia, platelet support therapy may be given by the oncologist. Adequate bleeding times are dependent on the extent of the oral procedure. The client also should be warned that trauma from improper toothbrushing or a poorly fitting dental prosthesis may initiate bleeding when platelets are low.

Salivary Gland Dysfunction

Not all persons on chemotherapy experience xerostomia or ropy saliva. Some clients, however, complain of a dry mouth, thickened secretions, or excessive drooling during chemotherapy. Studies are inconclusive as to the drugs’ effects on salivary glands; however, persons who complain about salivary dysfunction should be offered palliative measures such as adequate hydration (Table 44-2) to help manage this debilitating and uncomfortable side effect and to prevent further exacerbation of other oral complications.

Dental Caries

Rampant tooth decay is not directly caused by the toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs. However, clients with chronically dry mouths or persons who increase their intake of high-carbohydrate foods because of eating problems may experience an increase in caries development. For example, children who are chronically ill may be given nighttime bottle feedings and/or diets high in sugar. During periods of stress, parents and caregivers may allow an unbalanced diet to avoid additional stress from confrontation. Such eating patterns may increase dental caries risk.

Management

Depending on the severity of this problem, various preventive regimens may be prescribed. A fluoride rinse or brush-on 1.1% sodium fluoride gel may be adequate. If, however, there is evidence of demineralization and if dryness continues over months, the client may require custom-fit gel trays for daily gel application. In addition, in-office fluoride varnish applications may be beneficial. The dental hygienist educates about the importance of daily fluoride application, good nutrition, and oral hygiene. The dental hygienist also counsels clients and primary caregivers about cariogenic foods and behaviors and suggests alternatives (see Chapters 31 and 33).

ORAL CANCER–SPECIFIC THERAPY

Choice of treatment for oral squamous cell cancer depends on the stage of disease at the time of diagnosis. A small lesion of less than 1 cm may require only surgery or radiation therapy. Larger cancers, especially those that have spread to the lymph nodes in the neck, may require surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

Head and Neck Radiation

Radiation therapy employs the use of ionizing radiation, either from external beams or from internally implanted sources. Radiation therapy may be used by itself for the treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma when the lesion is small and superficial and when a surgical procedure would result in significant functional or cosmetic morbidity. Radiation also may be used in combination with chemotherapy, to enhance its ability to reduce the tumor, or with surgery, postoperatively to eliminate residual disease or preoperatively to reduce the size of the tumor. Radiation therapy also may be used in the treatment of other head and neck cancers, including lymphomas and salivary gland tumors.

Radiation damage to some normal cells (e.g., taste buds) may be acute and may resolve after therapy completion. Other normal cells affected (e.g., salivary gland cells) may not have the capacity to repair themselves, resulting in long-term complications. After the first week of radiation the client begins to experience some of the acute side effects (e.g., loss of taste and dry mouth), whereas other complications may not become evident until later in radiation therapy.

Oral Side Effects or Complications of Radiation Therapy

The complications associated with head and neck radiation will vary among clients, depending on the field and treatment and total dose of radiation required. Only the tissues in the direct field of radiation are affected. For example, a client undergoing lymphoma treatment may receive only 20 radiation treatments that involve only a portion of the salivary glands and cervical lymph nodes and will therefore experience fewer complications than a client who is undergoing treatment for a squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity. To avoid unnecessarily alarming the client, and to be able to offer sound advice, the dental professional must establish good communication with the radiation oncologist to understand the anticipated radiation side effects.

The client undergoing radiation therapy to the oral cavity and salivary glands begins to experience some side effects after the first week of therapy. Throughout therapy it is important to support the client with suggestions to prevent and reduce side effects or complications of radiation therapy. These complications are summarized in Box 44-8 and are described in the following paragraphs.

BOX 44-8 Potential Complications of Radiation to the Head and Neck Area

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health: Oral complications of cancer treatment: what the oncology team can do, Publication No. 99-4360, Bethesda, Md, 2008, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

Xerostomia and Salivary Gland Dysfunction

Salivary gland exposure to radiation is unavoidable during treatment for oral cavity and neck tumors because they are in close proximity to the lymphatic system and cannot be shielded. Ionizing radiation induces fibrosis and atrophy of the salivary gland tissue. Clients begin to experience a change in their saliva after the first week of radiation. They first complain of a thickened and ropy saliva, and as the treatments progress their mouths become drier. The degree of dryness is dependent on the radiation dose and the extent of salivary tissue within the radiation field. One study at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center demonstrated that persons undergoing high doses of radiation therapy to all of the major salivary glands experience a 67% decrease in saliva after 1 week of radiation, a 76% loss after 6 weeks, and a 95% loss 3 years after completion of radiation.

Xerostomia due to thickened, reduced, or absent salivary flow compromises speaking, chewing, and swallowing and increases risk of impaired nutrition owing to an inability to eat all foods. Persistent dry mouth also increases the risk of dental caries and other oral infections. Because the irradiated salivary glands are permanently damaged, the change in both the quality and the quantity of saliva remains, although the client may over time perceive a partial return in salivary flow. Clients often complain bitterly about the complications associated with xerostomia.

Management

Clients who undergo radiation therapy to the neck involving the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands with only partial inclusion of the parotid glands complain mostly of a thick, ropy saliva. These clients benefit greatly from baking soda and saline water rinses. A baking soda solution is mucolytic, which aids in cleansing and refreshing the mouth. A prescribed medication such as pilocarpine can be provided by the oncologist or dentist to help stimulate residual salivary gland tissue to produce saliva. Also, commercial saliva substitutes are available as over-the-counter products. Although the latter may be palliative, they do not contain the protective proteins and mucoproteins found in saliva, and some clients do not feel the cost is justified for the limited relief. In addition, the lips should be lubricated with a moisturizing lip balm or cream recommended by the radiation oncologist, not pure petrolatum, which provides only an occlusive agent and does not moisturize the perioral tissues. These and other suggestions for management of a dry mouth are listed in Box 44-9.

BOX 44-9 Recommendations for Clients with Xerostomia

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health: Oral complications of cancer treatment: what the oncology team can do, Publication No. 99-4360, Bethesda, Md, 2008, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

Alteration of Taste

When the tongue is in the field of radiation, the client experiences partial or full taste loss. Loss of taste is an acute effect and usually occurs after the first few treatments. Taste returns a few months after the completion of radiation therapy but may be altered from preradiation status. Taste loss is a significant side effect that makes radiation therapy almost intolerable. Eating becomes a chore; clients complain that all food tastes like mush or straw. Eating ceases to be a pleasurable activity, and clients must force themselves to eat to maintain nutritional status.

Management

Clients are helped by having someone listen to their complaints. They should be assured that taste dysfunction is a normal radiation side effect and that taste will return several months after treatment. In addition, clients should be encouraged to continue eating. Use of nutritional liquid substitutes such as Ensure and/or referral for nutritional counseling may be necessary to avoid weight loss and medical complications. If patients do not maintain adequate nutrition during the treatment process, then a stomach tube is surgically placed for liquid feeding at home.

Mucositis, Stomatitis, and Infection

If all nonsurgical dental or dental hygiene procedures have not been accomplished before initiation of radiation, they should be done within the first 2 weeks of therapy before the onset of mucositis. Usually, by the third week of radiation the client begins to experience mucosal inflammation and pain. Like chemotherapy mucositis, the mucosa first becomes edematous and inflamed, then the tissue becomes thinned, pseudomembranes form, and the tissue becomes denuded (see Figure 44-2). As the treatments progress, small ulcerations may enlarge to a confluent and pseudomembranous mucositis. Oncologists sometimes schedule a short interruption of therapy to allow regeneration of normal cells. Mucositis can increase the risk of severe pain, oral and systemic infection, unpleasant odors, difficulty in talking, and nutritional compromise. Lack of saliva increases ulceration and bleeding risk. Also, the patient may experience dysphagia (the inability to swallow) as a result of salivary gland dysfunction and painful ulcerated tissue within the radiation field.

Because of mucositis, secondary oral mucosal infections are common and may intensify the mucosal irritation. The fungal organism Candida albicans is most often implicated, but any organism may be responsible for infection when the tissues are severely compromised from xerostomia, mucositis, altered nutrition, and inadequate oral hygiene. Early detection and treatment of an oral infection are imperative to prevent exacerbation of mucositis that may require cancer therapy interruption. After all radiation treatments have been completed, gradual resolution of the mucositis can be expected, although the epithelium undergoes permanent fibrosis and the tissue may be thin and fragile and may show evidence of telangiectasia (a vascular lesion of dilated small blood vessels).

Management

Box 44-9 summarizes ways to help clients with mouth pain from mucositis. A clean, well-hydrated mouth during radiation therapy reduces the severity of mucosal ulceration and risk for oral infection. Toothbrushes are available that are supersoft and nonabrasive. Once the client begins to experience mucositis, it is necessary to modify oral hygiene procedures to be nonirritating and atraumatic but adequate to remove plaque biofilm and thickened saliva. Toothbrushes should be extra soft and may be further softened in hot water. Use of commercial toothpastes with strong flavoring agents may have to be temporarily discontinued and replaced with use of a paste made of baking soda and water. If toothbrushing becomes impossible because of painful tissues, the teeth, gingiva, and tongue may be swabbed with gauze moistened in warm water. Dental flossing should be continued as long as possible and resumed as soon as the mucositis resolves.

Sponge-tipped swabs are supplied for oral care to hospitals through medical supply companies but are not effective in plaque biofilm removal. However, if their use is necessary owing to ulcerated tissue, they should be dipped in a nonalcoholic antimicrobial solution for greatest efficacy.

All commercial mouthwashes with alcohol or phenol should be avoided because of their drying and irritating effects. Although half-strength peroxide and water solutions are sometimes used in hospitals to remove encrusted secretions or for acute infections, they are not recommended for long-term use because they are acidic and may alter the normal oral flora. Frequent mouth rinses with baking soda and saline water should be suggested. When the mouth is too sore to swish the mouth rinse, gentle irrigation of the mouth with a solution of 1 tsp of baking soda, 1 to 2 tsp of salt, and 32 oz of water can be recommended.

Chlorhexidine gluconate mouth rinse has not been shown conclusively to be beneficial in reducing oral infections and severity of mucositis during cancer therapy. Such a rinse, when prepared with alcohol, should be evaluated for its antimicrobial benefit versus the irritating effect of the alcohol. Topical anesthetics and coating agents in addition to the soothing bland rinses (see Table 44-1) give temporary relief. However, all clients, especially children and their parents, should be cautioned that topical anesthetic agents may anesthetize the soft palate and epiglottis, potentially causing aspiration of food. Excessive use also may potentiate mucositis. Some clients may require systemic analgesics and sometimes even narcotics to control the pain of mucositis.

During radiation therapy, perioral tissue care should be directed by the radiation oncologist. Some lip lubricants can potentiate the effects of the radiation and cause significant radiation dermatitis. Physicians order their preferred product for skin care during therapy.

Clients whose condition is not compromised should be scheduled for regular preventive oral healthcare. The role of the dental hygienist in providing professional mechanical oral hygiene care and supportive patient education is important to prevent mucositis and oral infection. Clients with dentures should be instructed to leave the dentures out of their mouths as often as possible. If the field of radiation encompasses all of the oral tissues, it may be impossible for the client to wear dentures because of significant oral tissue changes from edema and inflammation. The client should keep the dentures as clean as possible and store them in a soaking solution that is changed daily to avoid microbial contamination. These clients often eat a soft or liquid diet, and the tongue becomes coated and infected. Therefore keeping the mouth well cleansed and the tongue brushed are extremely important.

Trismus, Tissue Fibrosis, and Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction

Limited ability to open the mouth (trismus) may result from loss of elasticity of masticatory muscles or temporomandibular joint ligaments after a high dose of radiation. Trismus usually occurs within 3 months after therapy and remains a lifelong problem. It can result in significant discomfort and can interfere with eating, talking, and posttreatment examination.

Radiation Caries and Demineralization

Rampant caries and demineralization of the tooth structure usually begin within the first year after radiation therapy unless intensive oral hygiene and preventive measures are instituted. Figure 44-3 shows the typical clinical appearance of radiation-related caries. Enamel demineralization (loss of minerals without decay) and/or rapid decay is a result of changes in both the quality and the quantity of saliva after cancer treatment. The decreased salivary flow limits the availability of calcium and phosphate in the saliva to prevent the natural remineralization of the tooth structure and to buffer acids produced by cariogenic bacteria in the plaque biofilm. With dry and friable tissues, these clients may change to a soft, high-carbohydrate diet, adding to the lifelong risk of rampant dental decay.

Management

All clients receiving cancericidal doses of radiation therapy to any of the salivary glands must have custom fluoride trays made for daily application of a 1.1% neutral-pH sodium fluoride gel to aid in prevention of rampant tooth demineralization. The dental hygienist may be responsible for making impressions for study models to fabricate the custom tray. Impressions may be sent to a dental laboratory, or the trays may be made in the dental clinic using a vacuum unit. The fluoride trays are made from a soft, vinyl mouthguard material. They should be adapted to extend slightly above the cervical line of the teeth, with full coverage of all teeth. The tray edges must be absolutely smooth and nonirritating to the client’s oral tissues to prevent soft-tissue breakdown.

The client should begin use of the fluoride trays at the initiation of therapy. Clients are instructed to first brush and floss their teeth and then place a thin ribbon of 1.1% neutral-pH sodium fluoride gel in each of the trays. They place the trays on their teeth and leave them in place for 5 to 10 minutes. On removal clients rinse the trays well with water but do not rinse the mouth or eat anything for 30 minutes. This fluoride therapy must be done once each day. Many clients feel it is easiest to use the trays when they are bathing or showering. In this way, the procedure is incorporated into a regular daily routine.

There may be a period of time during therapy when severe mucositis prevents fluoride application with trays. During this time the client is encouraged to use nonalcohol and bland fluoride rinses, increase hydration of tissues, and resume the daily fluoride gel application as soon as the mucositis resolves.

In addition, dietary habits and daily food intake should be discussed to assess the intake of sugar, acidic juice, or soda pop (diet included). The dental hygienist plays a critical role in helping clients prevent radiation caries by educating them about the importance of daily fluoride application, good nutrition, and oral hygiene.

Altered Tooth and Jaw Development

The latent effects of therapeutic radiation therapy on children with cancers of the oral cavity and associated structures vary with radiation dose and field and stage of growth and development. Radiation has the potential to alter or arrest craniofacial growth and tooth development. Older children who receive minimal doses may experience only slightly altered root development, whereas younger children treated at an age when their jaws and teeth are under development may experience gross malformation of the dentition and may suffer significant skeletal deformities.

Soft-Tissue Necrosis and Osteoradionecrosis

Radiation therapy may irreversibly injure the vascularity of soft tissue and bone, resulting in decreased ability to heal if traumatized and in increased susceptibility to infection.5Osteoradionecrosis is defined as exposed bone that does not respond to treatment over a 6-month period of time as a result of radiation treatment. There is a higher risk of osteoradionecrosis as the dose of radiation and the volume of irradiated bone and tissue increase. Nonhealing soft tissue or bone may become secondarily infected, and the client may eventually experience intolerable pain and jaw fracture. The mandible appears to be more susceptible than the maxilla because of its dense bone and limited blood supply. Clients who are at the greatest risk are those who have surgery or trauma to irradiated tissue and bone and those who have dental infection in close proximity to bone compromised by radiation. Prevention of osteoradionecrosis by undergoing dental evaluation and treatment before radiation therapy is mandatory. After radiation the teeth and periodontium must be professionally managed at intervals to ensure excellent oral hygiene, early intervention, and minimal disease. The dental hygienist is an extremely important member of the professional team to manage this potentially very serious problem.

Surgical Treatment of Oral Cancer

Surgery is chosen as primary treatment when oral cancer is small; when the cancer is completely excisable without complication; when the cancer is not sensitive to radiation therapy; when lymph nodes, salivary glands, or bone are involved; or when there is a recurrence of tumor in an area that has already received a therapeutic dose of radiation. The disadvantage of surgery is the sacrifice of important functional oral structures.

Potential Complications

Physical

Acute physical complications after head and neck surgery may include infection; airway obstruction; fistula formation; necrosis in the surgical site; impairment of swallowing, hearing, vision, smell, and speech; and compromised nutritional status. Long-term complications include speech impairment, malnutrition from the inability to swallow foods, drooling, malocclusion, temporomandibular disorders, facial deformity, and chronic pain in the shoulder muscles.

Psychosocial

There may be significant psychosocial problems associated with head and neck surgery because the results of the cancer and its treatment are often visible and humiliating and can be psychologically devastating. Physical impairments cannot be completely disguised by clothing, prostheses, or cosmetics. These surgical defects may result in long-term disability, but these problems may be short-term when reconstructive surgery and rehabilitation are available. In today’s society, self-image is often equated with body image. As a result, some individuals experience depression, withdrawal and social death, anger, and stigmatization. Some who are heavy smokers and drinkers experience guilt because of the association of these habits with oral cancer.

Management

The person who has surgery for oral cancer often requires a long postoperative hospital course. To assist with postoperative management, a dental hygienist working in a hospital can do the following:

Provide in-service programs for nursing staff on oral assessment and oral hygiene care during cancer therapy.

Provide in-service programs for nursing staff on oral assessment and oral hygiene care during cancer therapy. Teach the client to maintain the oral cavity and all remaining teeth in optimal condition with frequent gentle cleansing and hydration. Cleansing and hydration are usually accomplished with irrigation bag or bulb syringe saline rinses and gentle debridement with large cotton-tipped applicators, sponge swabs, or gauze. Care must be taken when cleansing and suctioning not to disrupt new granulation tissue.

Teach the client to maintain the oral cavity and all remaining teeth in optimal condition with frequent gentle cleansing and hydration. Cleansing and hydration are usually accomplished with irrigation bag or bulb syringe saline rinses and gentle debridement with large cotton-tipped applicators, sponge swabs, or gauze. Care must be taken when cleansing and suctioning not to disrupt new granulation tissue. Encourage clients who have been cleared by the surgeon to take food by mouth to use a spoon to place small bites of food on the unaffected side of the mouth and as far back as possible. Forks should be avoided until incisions heal. (Immediately after surgery, a client may not be able to take food and drink by mouth, at which time a tube is placed in the stomach for liquid nutritional supplementation.)

Encourage clients who have been cleared by the surgeon to take food by mouth to use a spoon to place small bites of food on the unaffected side of the mouth and as far back as possible. Forks should be avoided until incisions heal. (Immediately after surgery, a client may not be able to take food and drink by mouth, at which time a tube is placed in the stomach for liquid nutritional supplementation.)A client who has had a recent head and neck surgical procedure may be in the process of accepting the facial deformity and functional alterations. Encouragement to talk about these issues aids the client in moving toward acceptance of the new body image. It is important for the dental hygienist to listen empathetically to the client's concerns and fears. Taking time to do so decreases client stress and promotes cooperation with recommendations. It is important to remember that although the surgical treatment may have removed head and neck tissue, it did not remove the person of the client. The client, as a whole person, has human needs related to oral health and disease. It is very important to actively listen to the client, communicate respectfully with good eye contact, and interact directly about ways to promote oral health and cope with the challenges that the surgery has presented.

Prosthetic Rehabilitation

Planning for rehabilitation of the person with head and neck cancer by the dentist begins at the time of medical diagnosis. When a surgical resection creates facial defects and oral dysfunction, the client must be assured that there is a plan to restore at least partial function and improve cosmetic appearance. The oral and maxillofacial surgeon, the maxillofacial prosthodontist, the general dentist, and the dental hygienist all may play a role in the initial care planning.

Maxillary defects result in unintelligible speech because of nasal voice quality, difficulty in eating, thickened nasal and sinus secretions, and facial disfigurement. Optimal management begins at the time of surgery, when the prosthodontist may place a surgical obturator (a temporary prosthetic device) to help correct these problems. Approximately 3 to 4 months after surgery, if no complications arise, a permanent prosthesis is fabricated. This prosthesis usually allows the most effective restoration for the client because speech, swallowing, mastication, and facial contour all can effectively be restored with a prosthesis instead of reconstructed with plastic surgery.

Mandibular defects are often created during oral cancer surgery. Immediate reconstruction is sometimes possible. After extensive intraoral surgery the client may need additional surgical procedures to release the tongue from the floor of the mouth, to graft skin, to create a vestibule for saliva pooling, and to allow for extension of denture flanges. These procedures also aid in speech, mastication, and swallowing.

After surgical and radiation therapy to the oral cavity, clients who are partially or fully edentulous require conservative prosthetic management. The thinned and friable tissue, scarring and fibrosis from surgery, and lack of lubrication and protective qualities of the saliva from radiation treatment make denture placement difficult and place the client at risk for soft-tissue breakdown and osteoradionecrosis. Some clients are never able to wear dentures. Detailed education, close professional supervision, and client acceptance of recommendations are necessary for successful prosthetic rehabilitation.

Bisphosphonates and Osteonecrosis

A potentially painful oral lesion related to a bone strengthening drug has become an additional concern for clients diagnosed with multiple myeloma or breast, thyroid, lung, or prostate cancer. These individuals may experience metastatic lesions or tumors that spread to the bones. The cancerous bone lesions can lead to hypercalcemia (excess calcium in the blood due to malignancy) and extreme pain and heighten potential for bone fractures. In order to diminish these conditions, oncologists often administer intravenously a class of medications called bisphosphonates (pamidronate [Aredia], zoledronic acid [Zometa], and clodronate [Bonefos]). These drugs alter or inhibit the ability of osteoclasts to resorb, thus suppressing bone turnover. As a result, bisphosphonates stabilize the skeletal matrix and reduce the formation of solid cancerous tumors attempting to spread from distant sites such as the lungs.7 Bisphosphonates are also prescribed in pill form (alendronate [Fosamax], risedronate [Actonel], and ibandronate [Boniva]) to treat osteoporosis and Paget’s disease of the bone; they act by increasing bone density.

A potential side effect of intravenously administered bisphosphonate is a condition called bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ). This often painful oral or extraoral lesion may resemble a osteoradionecrosis lesion and presents as an irregular ulceration with exposed necrotic bone (Figure 44-4). Bisphosphonate-related bone death in the mandible and maxilla is believed to occur as a result of the unique conditions to which the oral cavity is subjected. The mouth, unlike the rest of the body, is constantly being assaulted with small traumas through mastication or poorly fitting dentures as well as oral infection such as periodontitis and apical abscesses. When bisphosphonates are administered, they attach to the bone matrix and may remain in the bone for several years. The presence of this drug in the skeletal system prevents the jaw bones from the forming and reforming which are necessary for normal healing. If traumatized the bone may then become necrotic and form subsequent lesions. Typical symptoms include loose teeth, pain, drainage, swelling, a heavy feeling, or numbness.

Figure 44-4 A client with metastatic prostate cancer was treated with an intravenously administered bisphosphonate. Osteonecrosis of the right mandible developed after an extraction.

(Courtesy Dr. Salvatore Ruggiero.)

Approximately 0.8% to 12% of patients receiving intravenously administered bisphosphonates, and a much smaller number using oral bisphosphonates, develop BRONJ. Lesion development risk increases with the form, amount, and duration of bisphosphonate use.6 The majority of BRONJ lesions are reported to follow invasive dental procedures such as an extraction or implant placement, but BRONJ has also been reported to develop spontaneously in limited cases. Unfortunately, other than palliative care, there currently exists no effective way to treat BRONJ once it has formed.

Management

As with other aspects of cancer treatment, the dental hygienist remains an important treatment team member. In general, the guidelines developed for the oral and dental care of patients about to receive head and neck radiation therapy should be followed. Meticulous oral hygiene homecare and professional maintenance during cancer and bisphosphonate therapy can reduce the number of bacterial-induced pathology in the oral cavity, thus lowering the risk of developing BRONJ. In addition, the dental hygienist must carefully review the health history and explore any medications used during or after cancer treatment. Vigilance must be exercised during intraoral and extraoral examinations for evidence of BRONJ ulcers if an intravenous or oral form of bisphosphonates has ever been used. The patient also must be informed of risks associated with the use of both oral and intravenous bisphosphonates.

DENTAL HYGIENE PROCESS OF CARE

The dental hygienist, either as a member of a hospital oncology team (see the Web Resources section of the website) or as a clinician in consultation with the oncologist, has the opportunity to prevent and/or ameliorate many of the oral and systemic complications associated with cancer treatment by designing a dental hygiene care plan that promotes a clean and healthy oral cavity. Before the initial dental hygiene care appointment, consultation must be sought with other oncology team members involved in the care of the person with cancer. Open and continuous communication with physicians and nurses reduces the risk of providing care that compromises the client’s condition.

Assessment

The dental hygienist collaborates with the dentist to identify sources of infection that may delay postoperative healing for a client scheduled for surgery to the oral cavity. In addition, the pretherapy assessment also is critical for a client scheduled for intravenous bisphosphonate therapy or radiation therapy to the oral cavity and/or salivary glands. Any part of the maxilla and/or mandible that will be irradiated is at lifelong risk for the development of osteoradionecrosis. Therefore, all infections and teeth that cannot be maintained for the client’s lifetime should be identified for removal. Teeth to be extracted include not only those with gross caries and refractory periodontal disease but also those that potentially may not be maintained because of the client’s lack of personal motivation, physical or mental ability, and/or financial resources.

Because intraoral infection may spread through the bloodstream and result in sepsis and possibly death during immunosuppression, all potential sources of irritation that may potentiate mucositis also must be identified and eliminated. Assessment of a potential BMT recipient should identify any oral problem that may arise within the first year after the transplant when the client is in an immunosuppressed condition.

Client Interview

The client interview provides critical information that influences future oral hygiene care and dental treatment. Taking time to listen to the client’s perceptions decreases client and family stress, promotes consistency, encourages cooperation among members of the oncology team, and assists the dental hygienist in assessing the client’s human needs that shape the dental hygiene process of care.

The client's current oral status and health and dental histories are reviewed, including frequency of care, dental experiences that were unpleasant or painful, oral self-care habits, and current attitude and knowledge about the teeth and mouth. This information assists the dental hygienist in planning dental hygiene care. The interview also reveals the client’s socioeconomic status and cultural and ethnic influences that may affect perceptions of cancer, health beliefs, coping strategies, social support system, dietary habits, and ability to adhere to the supportive care.

Diagnosis

Dental hygiene diagnoses identify human needs related to direct dental hygiene care before initiation of cancer therapy, during therapy, and after the client has completed all proposed therapy. As therapy progresses and the client moves through various physical changes and psychosocial stages related to the cancer, the dental hygiene diagnoses change and the care plan is continually revised.

Planning

The client undergoing cancer therapy or in end-stage disease requires a care plan directed toward meeting actual or potential needs associated with the oral and systemic complications of cancer therapies.

Initially when clients are faced with a life-threatening cancer diagnosis, they are unable to conceptualize the importance of care beyond their most basic physiologic and survival needs. As these needs appear to be no longer at imminent risk, the client often begins to accept the diagnosis and may be capable of participating in supportive care. Clients in the dental office with a previously positive attitude about their teeth and oral hygiene may reveal totally different values during times of stress. It cannot be assumed that clients involved in cancer therapy will continue the previous level of personal oral hygiene care. On the other hand, it should not be assumed that persons with a seemingly overwhelming cancer diagnosis do not have the ability to participate in successful rehabilitation. At appropriate times, a clear understanding of the oral problems associated with cancer therapy must be effectively communicated and trust established by mutual participation in the development of oral health goals.

Oral and Dental Management before Cancer Therapy

Referral to a Dentist

Conditions found by the dental hygienist that require diagnosis by a dentist should be referred immediately for evaluation and treatment. Before chemotherapy begins, clients should have all surgical procedures done at least 7 days before periods of immunosuppression, all sources of infection and irritation removed, and all projected dental needs met. For clients scheduled for surgery, all oral surgical procedures need to be scheduled 14 to 21 days before initiation of radiation therapy to the oral cavity and salivary glands. Restorative needs should be cared for before the onset of painful mucositis. Fabrication of new dental prostheses is delayed until several months after radiation therapy ends, when all acute side effects of radiation have resolved (Box 44-10).

BOX 44-10 Reasons for an Oral Evaluation before Cancer Treatment

Psychosocial Issues

The initial client appointment is an important time when trust and assurance are established. Clients must feel acceptance in a nonjudgmental environment and sense that their self-esteem will be preserved. The client is a “person living with cancer,” not a “cancer case.” Additional time is necessary to allow the client to express feelings. All feelings should be acknowledged, and anger should not be mitigated too quickly. The client should be encouraged to participate in care planning, which provides an opportunity to regain some of the sense of control that was lost to the cancer.

Education

Adequate time must be allotted for education because the stress related to a cancer diagnosis can easily impede the normal learning process. It is important to engage in the teaching process with full regard for the client’s psychologic human need status. Clients in a state of denial are not able to comprehend the importance of preventive oral healthcare until they begin to accept their cancer and therapy plan. Others, stressed by the financial burden of medical treatments, may not place priority on dental and dental hygiene treatment when compared with their impending lifesaving cancer therapy. Those who are depressed and see their prognosis as grave do not value the importance of long-term dental hygiene care until they begin to see cause for hope.

Oral Hygiene Instruction and Self-Care

Oral hygiene self-care assistance is important before cancer therapy initiation to establish good hygiene before the oral tissues are compromised. Disclosing agent use aids in instruction and helps the client identify areas that need closer attention in self-care procedures. This educational approach also provides an opportunity for the dental hygienist to explain the composition of plaque biofilm and the risk of oral and systemic infections during cancer therapy. Oral hygiene technique should be assessed, if possible, and the client assisted in establishing plaque removal techniques that will be useful before and during therapy. If a client is scheduled for therapy that will significantly compromise the oral tissues, initial instruction should be given verbally and in print regarding methods for cleansing the mouth and preventive and palliative products recommended (see Table 44-1). These methods are then elaborated on during therapy. Gentle tooth and gingival brushing can continue during cancer therapy.

Tobacco and Alcohol Cessation Counseling

Usually the oncologist strongly urges the client to stop using tobacco products and to limit excessive alcohol intake during cancer therapy. Tobacco cessation support and assistance from the dental hygienist are important (see Chapter 34). Referral to the national tobacco cessation quitline (1-800-QUITNOW), a local tobacco cessation program, or a support group may be necessary and desired by the client.

Nutritional Counseling

Clients' nutritional status affects their overall response to cancer therapy and their psychologic well-being. The nutritionist on the oncology team assumes primary responsibility for monitoring the client’s nutritional status and providing counseling on diet selection. The dental hygienist consults with the nutritionist and educates the client about diet selection and dietary habits to promote a clean and healthy oral environment and to reduce caries development. It is important for the dental hygienist to determine the client's understanding of the relationship of a well-balanced diet to dental caries, periodontal disease, and infection. When the client is ready psychologically to assimilate preventive behaviors, the client and the dental hygienist choose foods that are desirable to the client but are low in sugar, acid, and oral retention qualities. The client needs to understand, however, that it is often difficult during therapy to eat a well-balanced diet containing foods that promote oral health.

Dental Hygiene Instrumentation

Dental hygiene instrumentation may need to be altered to accommodate the client's physical condition related to recent surgery, disease manifestations, and the status of the client’s blood counts and clotting factors. The oncologist is consulted regarding the safest time to schedule an appointment and the need for antibiotic prophylaxis before dental hygiene instrumentation. Overall, dental hygiene care promotes a clean and well-hydrated oral environment and control of periodontal disease to reduce the risk of oral infection and bacteremia.

Fluoride Therapy

When the client is scheduled for radiation therapy to the salivary glands or TBI for BMT, custom fluoride gel trays are fabricated for daily application of a 1.1% neutral-pH sodium fluoride gel to prevent rampant dental caries. Clients who complain of a dry mouth during chemotherapy require at least a daily fluoride rinse and possibly a 1.1% sodium fluoride toothpaste or gel.

Oral and Dental Care during Cancer Therapy

Once therapy is initiated, it is important to continue to support the client and to understand that most cancer therapy is physically and psychologically demanding. With each appointment the dental hygienist repeats the oral assessment, updates the health history, and assesses the client’s level of disease acceptance and readiness for new interventions. Clients’ anger and bargaining may be signs of acceptance of the diagnosis and an attempt by clients to regain control of their own lives. These times offer the dental hygienist an opportunity to direct the client’s interest to positive involvement in oral self-care and dietary planning. Education during care is centered on the immediate real and impending complications of therapy.

Management of Oral Complications

Table 44-2 summarizes dental hygiene interventions that may prevent or ameliorate the oral complications associated with radiation and chemotherapy.

After a client scheduled to undergo BMT enters the transplant center, the client is not allowed to leave the unit until the bone marrow has engrafted and blood counts have returned to a normal range. Therefore all dental treatment must be accomplished before the transplant.

Nutritional Counseling during Cancer Therapy

Cancer therapy side effects often result in high risk for dental caries. Clients may be placed on a soft and bland diet or liquid high-carbohydrate diet because of recent oral surgery or mucositis from therapy. They also may be encouraged to eat small, frequent meals and snacks to increase their caloric intake and to counteract nausea and vomiting. Additional complications arise from a dry mouth or thickened saliva, taste dysfunction, inability to practice good oral hygiene because of an oral surgical procedure, and/or a lack of interest in eating because of depression and stress. A severely malnourished client may be placed on parenteral nutrition, completely eliminating the mechanical oral cleansing action of foods.

Diets of children during cancer therapy are often a problem because there are so many times when they are too sick to eat that parents allow them to eat anything they want when they are feeling well. In working with the nutritionist, the dental hygienist continues to emphasize the importance of a well-balanced, low-sugar diet for prevention of infection and promotion of healing after the insult of therapy.

Clients with mouth pain may be helped by suggesting use of a topical anesthetic or coating agents before eating (see Table 44-1). Also, clients with oral ulcerations or dry mouth may find it helpful to eat foods high in moisture, or they may thin their food with liquids and take frequent sips of water while eating. Irritating hot, spicy, or acidic foods should be avoided.

Oral and Dental Care after Cancer Therapy

After any kind of cancer therapy the dental hygienist continues to have an important role in client care. At each client appointment, the dental hygienist reassesses the client's human needs related to oral health. Even when clients have been reassured that their cancer has successfully responded to therapy, they continue to experience stress, anxiety, and concern about possible recurrence of the cancer. Continued education and frequent contact and support are essential. The dental hygienist tailors the client’s oral self-care to the individual’s status and human needs and places as much responsibility on the client as possible.

After Chemotherapy

After a client has completed the required rounds of chemotherapy, most of the oral manifestations completely resolve. With full bone marrow recovery, all problems associated with acute cytotoxicity, immunosuppression, and thrombocytopenia disappear. Some clients, after long and intensive chemotherapy, take months to recover fully and experience chronic oral infections such as candidiasis and herpetic infections. Continual assistance with oral hygiene is required to prevent unnecessary infections. Assessment of clients’ nutritional intake is important to determine if they have resumed a noncariogenic and normal diet.

After Bone Marrow or Blood Stem Cell Transplantation

After clients are released from a transplant unit they may have residual effects of the conditioning phase of treatment and may remain susceptible to infections for several months because of immunosuppressive therapy. Some continue to experience xerostomia, which predisposes them to an altered oral flora and infections, trauma, and rampant dental caries. Clients with GVHD may experience additional complications of thinned and friable mucosa and mucosal lesions.

The dental hygienist assists the client in establishing consistent and effective oral hygiene methods that do not create additional trauma and irritation. Bland rinses, gentle but thorough and consistent cleansing of the teeth and tissues, and saliva substitutes are important.

Dental procedures deemed necessary are done only after consultation with the oncologist to assess the client's immune status and need for antibiotic prophylaxis or platelet support. Elective dental procedures are delayed until the client has full hematologic function, sometimes up to a year or longer after treatment. Rampant dental caries from xerostomia are prevented with daily application of fluoride gel in custom fluoride trays.

After Radiation Therapy

Client care after radiation therapy specific to the oral cavity and salivary glands requires lifelong frequent dental and dental hygiene maintenance care. Because damage to the salivary glands and jaw bones from cancer radiation therapy is permanent, clients are at permanent risk for development of rampant “radiation caries,” demineralization of the tooth structure, and/or osteoradionecrosis. Continued-care appointments are scheduled at intervals to ensure excellent oral hygiene, sound tooth structure maintenance, and avoidance of soft-tissue irritation. The daily use of the custom fluoride trays with 1.1% neutral-pH sodium fluoride gel for 5 to 10 minutes followed by 30 minutes of abstinence from food and water must continue for the rest of the client’s life. If there is evidence of dental decay despite compliance with daily fluoride applications, the client should be placed on a 2-week chlorhexidine regimen to decrease cariogenic bacteria and scheduled for in-office fluoride varnish applications. A daily remineralizing gel application may also be necessary in addition to the daily fluoride gel application.

With each appointment, the dental hygienist assesses the client’s nutritional status and dietary intake. Adjustments are made to return to a normal and noncariogenic diet as the acute radiation therapy side effects resolve. Referral for nutritional counseling may be necessary.

A thorough head and neck assessment for oral cancer and function of the muscles of mastication, the temporomandibular joint, and prosthetic appliances is done at each appointment. Deficits in the needs for integrity of the skin and mucous membrane of the head and neck and for biologically sound dentition require immediate referral to the dentist. Dental disease in an area of irradiated bone is managed as conservatively and as atraumatically as possible by the dentist; management sometimes includes antibiotic prophylaxis. If trismus occurs, treatment consists of introducing tongue blades between the teeth for several minutes each day, gradually increasing the number of blades until adequate opening is achieved. This strategy may be painful and requires patience and perseverance. Dental treatment of osteoradionecrosis is conservative but generally requires conservative surgical removal of necrotic tissue, antibiotics to prevent infection, and, ideally, hyperbaric oxygen therapy to stimulate visualization and new bone growth. When conservative measures fail,surgical resection is usually indicated.

Clients with End-Stage Disease

Oral and dental care is sometimes ignored during this stage of life, but a mouth free of discomfort and bad odors is extremely important. The mouth becomes the center of existence during terminal disease because it maintains nutritional status and is used to communicate needs and emotions to loved ones. A mouth free of bad odors helps to maintain self-esteem and aids in social communication, preventing some of the loneliness experienced during the terminal stage. All care must be designed to provide quality of life and the best care for the client's needs. Care that enhances the person's dignity and facilitates personal comfort, normal eating, and social communication is of critical importance.

The dental hygienist educates family, hospice volunteers, and other caregivers about the importance of oral hygiene for the client. Many people do not realize how important the mouth becomes to the dying individual. Simple explanations and procedures related to oral hygiene reduce the stress related to this time. Such explanations may also provide a significant opportunity for family members to assist in the care of their loved one, because oral hygiene care aids so much in their overall comfort. This assistance with care may be especially important for parents of dying children. Many medical procedures must be performed by nurses or physicians, but oral care procedures are simple and provide an opportunity for the parent to participate with tender care.

Evaluation

Client goals planned for dental hygiene care vary tremendously, depending on the client's human needs assessment, stage of the disease, treatment, and psychologic status. Goals and outcomes of care are evaluated repeatedly by assessing clients’ responses as they move through the various treatment phases and psychologic adjustments to their disease. Outcomes of care are evaluated based on whether the planned goals are met, partially met, or unmet.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Educate clients about the potential oral complications associated with the type of cancer therapy they will undergo and about ways in which such conditions can be prevented or ameliorated.

Educate clients about the potential oral complications associated with the type of cancer therapy they will undergo and about ways in which such conditions can be prevented or ameliorated. Emphasize the importance of excellent oral hygiene during cancer therapy. Individualize self-care plans based on the proposed cancer therapy and the client’s needs.

Emphasize the importance of excellent oral hygiene during cancer therapy. Individualize self-care plans based on the proposed cancer therapy and the client’s needs.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

KEY CONCEPTS

Cancer is a term that defines a broad variety of malignant processes, usually treated with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or bone marrow or blood transplantation.

Cancer is a term that defines a broad variety of malignant processes, usually treated with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or bone marrow or blood transplantation. Approximately 40% to 80% of persons treated for non–head and neck malignancies experience oral complications.

Approximately 40% to 80% of persons treated for non–head and neck malignancies experience oral complications. Pre-existing oral or dental pathology can adversely affect the individual undergoing cancer therapy.

Pre-existing oral or dental pathology can adversely affect the individual undergoing cancer therapy.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Profile: A 45-year-old woman with a soft-palate lesion and a large right-neck mass. The biopsy reveals squamous cell carcinoma. She is scheduled for surgery followed by unilateral radiation therapy to the right posterior mandible and maxilla and lateral neck.

Chief Complaint: “I need a dental evaluation and dental hygiene care before starting my cancer therapy.”

Dental History: Her pretherapy radiographic and clinical oral and dental evaluation reveals no dental caries, generalized gingivitis, and moderate plaque, calculus, and tobacco stain.

Social History: Client is single and lives with her parents.

Health History: Client has been diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the soft palate. She currently takes no medications, and her blood pressure is within normal limits.

Oral Health Behavior Assessment: Client states that she brushes her teeth once a day, does not use floss, and visits her dentist every year. She takes OTC antacids, chewable vitamin C, and Aspergum for her sore throat. She has smoked one or two packs per day for 25 years.

Supplemental Notes: She has dental insurance, demonstrates a sincere interest and motivation to maintain her teeth, and is very interested in tobacco cessation intervention.

Profile: A 23-year-old woman who has been undergoing radiation for Hodgkin’s disease.

Chief Complaint: “I need a dental evaluation and necessary treatment before the next phase of my cancer therapy.”

Social History: She is single and lives alone.

Health History: She is scheduled for an allogeneic bone marrow transplant for which she will receive total body irradiation and chemotherapy. She will enter the bone marrow transplant unit in 3 weeks.

Dental History: She had no dental support during her previous cancer treatment. Her dental evaluation reveals a sensitive maxillary premolar with a large carious lesion and radiolucent periapical lesion, several areas of mild demineralization, moderate plaque and calculus, and chapped lips. No other gross caries or periodontal disease is evident. There are no impacted teeth or bony lesions detected by radiographs.

Oral Health Behavior Assessment: She reports that she brushes her teeth once a day but does not use any interdental cleaning devices.

Supplemental Notes: She has dental insurance and appears motivated to improve her oral hygiene care.

1. Espey D.K., Wu X., Swan J., et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska natives. Cancer. 2007;110:2119.

2. American Cancer Society: Cancer facts and figures 2008 Available at: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/2008CAFFfinalsecured.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2008

3. Reis LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al, eds: Seer cancer statistics review, 1975-2005, Bethesda, Md, 2008, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/index.html. Accessed October 8, 2008.

4. Sturgis E.M., Cinciripini P.M. Trends in head and neck cancer incidence in relation to smoking prevalence: an emerging epidemic of human papillomavirus–associated cancers. Cancer. 2007;110:1.

5. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health: Oral complications of chemotherapy and head/neck radiation (PDQ), health profession version. Available at: www.nci.nih.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/oralcomplications. Accessed October 2007.

6. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws, approved September 25, 2006. Available at: www.aaoms.org/docs/position_papers/osteonecrosis.pdf. Accessed November 2007.