Chapter 31 Fracture of the Navicular Bone and Congenital Bipartite Navicular Bone

Fractures of the navicular bone occur in a variety of configurations. The most common is a slightly oblique parasagittal fracture, medial or lateral to the midline. Y-shaped fractures and other comminuted fractures are less common. Avulsion of the entire distal border is rare. Distal border fragments are discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 30). Fractures occur more commonly in forelimbs than hindlimbs. In a series of 40 horses with navicular bone fractures, 28 (70%) occurred in a forelimb.1 Fractures usually are traumatic in origin, although it is not always possible to identify the cause. Some fractures in hindlimbs have been the result of kicking a wall. Bipartite and tripartite navicular bones have also been described and should be differentiated from a fracture.2 These may occur unilaterally, bilaterally or sometimes in 3 or 4 limbs in forelimbs or hindlimbs. It has been suggested that many fractures are pathological secondary to severe navicular disease,3 but this confusion probably arises because lucent zones adjacent to the fracture line and along the distal border of the navicular bone develop rapidly, within months of fracture occurrence.4 Palmar (plantar) displacement of fracture fragment(s) may result in laceration of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT).5 Other fractures of the middle or distal phalanx occasionally occur concurrently.

History

Lameness associated with a fracture is usually acute in onset and severe. However, sometimes a horse may develop less severe lameness, and radiographic examination reveals evidence of an old fracture, which presumably healed by fibrous union but has recently become unstable. Instability between separate ossification centers can cause unilateral or bilateral mild to moderate lameness or occasionally lameness in three or four limbs.

Clinical Examination and Diagnosis

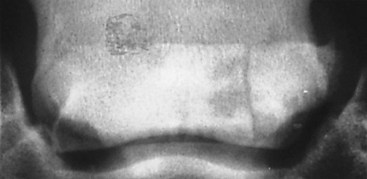

A horse with a fracture may be reluctant to bear full weight on the limb. Digital pulse amplitudes may be increased, and in some horses, pain can be elicited by application of hoof testers to the heel or frog regions. Percussion of the frog may be resented. Lameness usually is severe with an acute fracture and may be accentuated as a horse turns. Lameness is usually substantially improved by perineural analgesia of the palmar digital nerves, although it sometimes is unaffected. Diagnosis depends on radiological identification of the fracture(s). Most fractures are best identified in a dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique image (or an “upright pedal” plantarodorsal image in a hindlimb) (Figure 31-1). It is important that frog cleft artifacts not be confused as a fracture. The clinician should examine any radiolucent line carefully to see whether it extends beyond the bone margins or changes position relative to the medial and lateral margins of the bone if the x-ray beam is reoriented 5 degrees medially or laterally. The frog clefts should be well packed with a moldable compound (e.g., Play-Doh, Hasbro, Pawtucket, Rhode Island, United States) and, if necessary, repacked. If doubt persists, a weight-bearing dorsopalmar view and a palmaroproximal-palmarodistal oblique image of the navicular bone should determine whether a fracture is present. The palmaroproximal-palmarodistal oblique image is also useful for determining the presence of comminution or displacement. The presence of radiolucent zones along the fracture line indicates that it is not of recent origin but rather is likely to have been present for at least several months (Figure 31-2). With fractures of unusual configurations occasionally radiological findings are equivocal or negative and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography is required for diagnosis.

Fig. 31-1 Dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique radiographic image of a navicular bone. There is an acute parasagittal fracture lateral to the midline. Lateral is to the right.

Fig. 31-2 Dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique raidographic image of a navicular bone with a chronic fracture involving the lateral aspect. There are large radiolucent areas adjacent to the fracture line and modeling of the lateral proximal margin of the navicular bone.

A bipartite, or less commonly a tripartite, navicular bone is usually characterized by a wider gap between the ossification centers than an acute fracture. There may or may not be radiolucent zones adjacent to the radiolucent gap between the bone fragments. Occasionally this is an incidental finding unrelated to current lameness. Alternatively, it may be seen in association with foot pain resulting from another related cause, such as a DDFT lesion in the same parasagittal plane. In such horses there is no increase in radiopharmaceutical uptake in the navicular bone, whereas in horses with fractures or bipartite navicular bones contributing directly to pain and lameness there is increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the navicular bone. Bipartite navicular bones may be present in more than one limb, and if lameness is unilateral, it is recommended that the contralateral limb is also examined radiographically.

Proximal displacement of a hindlimb navicular bone secondary to complete rupture of the distal sesamoidean ligament has been reported in a steeplechaser.6 The navicular bone was displaced proximally in a lateromedial radiographic image. The horse was managed conservatively and did return to racing.

Treatment

Lameness associated with a simple sagittal fracture usually improves progressively with rest, but the prognosis for complete resolution of lameness or return to full athletic function is guarded. Some horses do become sound enough for light hacking, but lameness may be recurrent.3,7 Better results have been described in a limited number of horses by trimming the foot to establish a normal hoof-pastern axis followed by application of four 3-degree wedge pads and a flat shoe to reduce the weight-bearing function of the navicular bone.8 The horse is confined to box rest for 60 days and then starts walking exercise for an additional 2 months. The shoe is refitted every 4 weeks with 3 degrees less elevation at each shoeing. However, healing probably is only by fibrous union. Treatment by palmar digital neurectomy may provide symptomatic relief in some horses, but a substantial proportion develop osteoarthritis of the distal or proximal interphalangeal joints and associated lameness.7 Internal fixation using a lag screw technique with a specially designed limb jig and radiographic control offers the best prognosis for simple, oblique sagittal fractures.1,9 Twenty-three (68%) of 40 horses resumed work. The prognosis was significantly better for horses with fractures of less than 4 weeks’ duration than for those with older fractures. Potential complications include splitting the fragment, inability to reduce the fracture resulting in a step deformity, and poor stabilization of the fracture. Experience with MRI has shown that in association with an acute fracture there may be concurrent lesions of the DDFT, which may influence prognosis. The prognosis for horses with more complicated fractures is guarded.

Palmar digital neurectomy has been used successfully in horses with lameness associated with a bipartite navicular bone; however, it is important to be aware that there may also be a related DDFT injury.