Chapter 57Physitis

Physitis occurs in the horse in three principal forms: infectious physitis and type V and type VI Salter-Harris growth plate injuries.1 Type V growth plate injury can arise secondary to congenital but persistent angular limb deformities in foals, but these, infections, and type VI injuries are not considered in this chapter. Type V Salter-Harris injuries are considered a manifestation of acquired physitis, one of the group of disorders known as developmental orthopedic disease.2 The inclusion of acquired physitis under the umbrella of osteochondrosis may be more debatable. Jeffcott3 considered that the condition was better defined as physeal dysplasia, implying a disturbance of endochondral ossification rather than an inflammatory condition. Bramlage4 outlined two forms of physitis based on radiological interpretation of the site at which changes were seen. The two forms were those that were seen at the periphery, usually on the medial aspect, and those that were seen in the axial or central section of the growth plate.

Physitis is largely confined to the lighter-boned, faster-growing breeds of horse, particularly Thoroughbreds and Thoroughbred crossbreeds. Milder physitis is relatively common, and rarely does experienced stud management allow the condition to develop far enough for severe lameness and conformational changes to occur. Only in horses with more extreme or persistent physitis would radiographic examination be undertaken in the United Kingdom. Clinical recognition of enlargement of the growth plate or slight change in conformation usually results in a presumptive diagnosis of physitis and indicates an immediate change of the horse’s management as the first line of treatment.

Pathogenesis

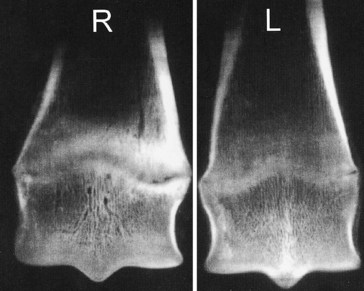

I consider the pathogenesis of physitis to be consistent with a type V Salter-Harris growth plate injury. This implies a compression lesion that arises medially as a consequence of the greater weight being borne on the medial aspect of the forelimb. Although the medial aspect of the forelimb is the most frequent site, physitis also occurs laterally in a foal with a carpal valgus deformity. Physitis arises at a time in the most active growing phases of young horses, when endochondral ossification is at its peak in the affected physis. It also occurs in the contralateral limb after a chronic lameness, at the fetlock in a younger foal, or at the carpus in older foals and yearlings. For example, I have encountered physitis in the contralateral forelimbs of foals with severe acquired flexural deformity of the distal interphalangeal joint (Figure 57-1). Although physitis may result in an upright conformation of the fetlock joint, probably from off-loading the limb to relieve pain, physitis does not cause other flexural deformity.

Fig. 57-1 Dorsopalmar radiographic images of frontal sections of the distal aspect of the third metacarpal bones of a 5-month-old foal with chronic and severe flexural deformity of the left (L) distal interphalangeal joint and physitis in the contralateral distal metacarpal physis (R). Note the more intense mineralization of the growth plate cartilage and bridging at the medial aspect (to the right of the image) of the right forelimb, typical of Salter-Harris type V growth plate injury.

Physitis is more common on farms that use rigorous or heavy feeding programs. Owners whose stock lives on lush pasture and is supplemented with concentrate feed have a higher incidence of physitis among their horses than those who keep their horses on leaner management. A higher incidence of developmental orthopedic disease is noted in foals and yearlings raised on young (<7 years old) pastures.

I have seen balanced mineral supplementation and withdrawal of concentrates dramatically reduce the incidence of physitis on some farms. Diet and forage analysis can be helpful when high incidence of developmental orthopedic disease is persistent (see Chapter 55), but mineral clearance ratios (creatinine phosphate in particular) are rarely necessary to adjust supplementation. Certain mares may also produce more foals with physitis compared with similarly managed mares, which implies a hereditary predisposition.

Clinical Signs

Clinical physitis is recognized at three main sites: the distal aspect of the third metacarpal or metatarsal bone, the distal aspect of the radius, and, less frequently, the distal aspect of the tibia. During lameness investigations, physitis has been noticed at other sites, such as the distal aspect of the femur and cervical vertebrae.

Physitis is seen in the fetlock region in foals aged 3 to 6 months and occurs at the distal aspect of the radius from 8 months to 2 years of age. Clinical signs are characterized by firm, warm, and painful enlargement of the growth plate, most commonly on its medial aspect. The proximal physis of the proximal phalanx also may be enlarged at the fetlock, giving the fetlocks an hourglass shape when viewed from the dorsal aspect (Figure 57-2). Early signs at the distal radial or tibial growth plates include a convex appearance in the medial contour of the metaphysis just proximal to the physis; this should be a straight or slightly concave outline. Swelling also is located around the distal dorsomedial aspect of the radius (Figure 57-3). This dorsal component can lead the clinician to suspect that the condition has arisen from external trauma. As with the fetlock joint, warmth on palpation is present, as is tenderness when pressure is applied across the growth plate while the leg is held partially flexed. Full and forced flexion of the fetlock, carpus, or tarsus also may be resented. Most affected horses have changes at the distal medial aspect of the radius, but a few with preexisting carpus valgus conformation may develop the condition laterally. Bilateral lameness may be seen as a stilted gait. The conformation may become more upright through the pastern, and fetlock varus deformity may develop because the horse walks on the outside of the hoof to alleviate pain from pressure on the medial physis. I suspect that foals and yearlings that develop a carpus varus conformation (start to go bandy) are likely to have a subclinical form of physitis that encourages them to bear more weight on the lateral aspect of the forelimbs. If physitis continues unchecked, growth ceases on the medial side, exacerbating the carpus varus deformity, and ultimately, premature closure of the growth plate fixes the abnormal conformation. This chain of events also occurs in horses that develop physitis in the distal lateral aspect of the radius, resulting in a permanent carpus valgus conformation.

Treatment

Treatment centers on stable rest. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs can be helpful, particularly in horses that are very lame or have inflamed and painful growth plates. I have no experience of using corticosteroids or anabolic steroids in horses with physitis. Although body condition and conformation can vary, it is important to assess the nutrition of affected foals and other horses. Reduction of body weight and particularly a reduction in energy content in the diet must be made. Starving these horses completely is unwise, and it is important that mineral intake includes the correct balance of calcium and phosphorus and adequate copper and zinc. The length of rest required varies with the severity of the physitis and ranges from 2 weeks to 2 months. Corrective hoof trimming must also be undertaken, especially if the horse has developed an angular limb deformity (see Chapter 58). For varus deformity the unworn medial hoof wall must be removed (inside is lowered), and if the angulation is severe, fitting a lateral hoof extension is necessary.

Surgery usually is unsuccessful in horses that develop severe varus limb deformity resulting from physitis. This experience, coupled with the disappointing results obtained when operating on yearlings with congenital angular deformities, has led me to stop recommending periosteal elevation or physeal retardation techniques in these groups of affected horses.

The prognosis for racing or other extreme athletic activities is good, provided the condition was not so severe that the conformation is permanently affected. If carpus varus and bench-knee conformation is marked, then the animal is likely to develop lameness from splints, carpitis, sesamoiditis, or suspensory branch desmitis when more serious training is undertaken.