Chapter 92Acupuncture

Equine Acupuncture for Lameness Diagnosis and Treatment

Equine Acupuncture for Lameness Diagnosis and Treatment

Interest in veterinary acupuncture for lameness diagnosis and treatment has increased greatly in the public and veterinary medical communities. With this increased awareness has come an increase in veterinary acupuncture research and thus a better understanding of the physiological basis of acupuncture and its clinical applications. Acupuncture may be used as an adjunct diagnostic and therapeutic tool to our traditional lameness examination and to the treatment of lameness, but it is not meant to be a substitute.

With the increased interest in equine acupuncture, there has also been additional controversy and use and misuse of this modality. It is important to understand the scientific basis, traditional Chinese medical theories, and clinical indications and limitations if acupuncture is to be used in a professional manner as part of an integrated approach to equine lameness. Currently, equine acupuncture is practiced by veterinarians trained in the Western medical perspective of scientific acupuncture and the traditional Chinese and Japanese medical theories. The approach may vary slightly based on the practitioner’s perspective.

The history of equine acupuncture dates back to 2000 to 3000 bce during the Shang and Chow dynasties in China. Around 650 bce Bai-le wrote Bai-le’s Canon of Veterinary Medicine, one of the first veterinary textbooks, which described acupuncture and moxibustion in equine medicine. The first atlas of equine acupuncture points and channels, Ma Jing Kong-xiue Tu, was written during the Sui period, from 581 to 618 ce.1 Equine back pain was first addressed in the ancient veterinary textbook Yuan-Heng Liao Ma Ji (Yuan-Heng’s Therapeutic Treatise of Horses).2 Periodically, anecdotal reports of using equine acupuncture would come to the Western world. The first substantial introduction occurred in the 1970s, when the International Veterinary Acupuncture Society was established and developed training programs in veterinary acupuncture in the United States. In 1996 the American Veterinary Medical Association stated, “Veterinary acupuncture and acutherapy are considered valid modalities, but the potential for abuse exists. These techniques should be regarded as surgical and/or medical procedures under state practice acts. It is recommended that extensive continuing education programs be undertaken before a veterinarian is considered competent to practice acupuncture.”3 Postgraduate education in veterinary acupuncture throughout the world—including Australia, Europe, Scandinavia, North and South America, and other areas—is offered by the International Veterinary Acupuncture Society, based in Fort Collins, Colorado.4 The Chi Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Reddick, Florida5; Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine continuing education program in Fort Collins, Colorado6; Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine in North Grafton, Massachusetts7; and the Veterinary Institute for Therapeutic Alternatives in Sherman, Connecticut8 also offer postgraduate programs. All of the programs are in the United States.

Scientific Basis

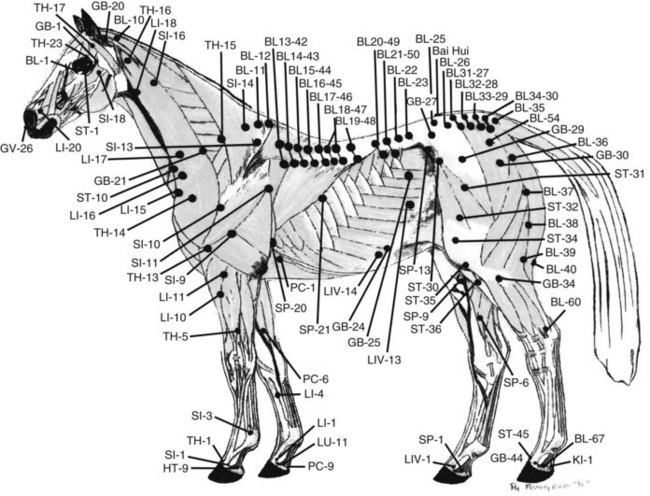

Acupuncture may be defined in a Western medical perspective as the stimulation of specific predetermined points on the body to achieve a therapeutic or homeostatic effect. Recent research has provided evidence for the anatomical classification of acupoints. Acupuncture points are areas on the skin of decreased electrical resistance or increased electrical conductivity. Acupuncture points correspond to four known neural structures. Type I acupoints, which make up 67% of all acupoints, are considered motor points. The motor point is the point in a muscle that, when electrical stimulation is applied, will produce a maximal contraction with minimal intensity of stimulation. Motor points are located near the point where the nerve enters the muscle. Type II acupoints are located on the superficial nerves in the sagittal plane on the midline dorsally and ventrally. Type III acupoints are located at high-density foci of superficial nerves and nerve plexuses. For instance, acupoint GB-34 is located at the point where the common fibular (peroneal) nerve divides into the deep and superficial branches. Type IV acupoints are located at the muscle-tendon junctions, where the Golgi tendon organ is located.9 Recently, histological studies have revealed that small microtubules, consisting of free nerve endings, arterioles, and venules, penetrate through the fascia at acupuncture points (Figure 92-1).10

Fig. 92-1 Schematic drawing of the skin, showing a neurovascular bundle wrapped by a sleeve of loose connective tissue deep to an acupoint.

(From Schoen AM, ed: Veterinary acupuncture: ancient art to modern medicine, ed 2, St Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

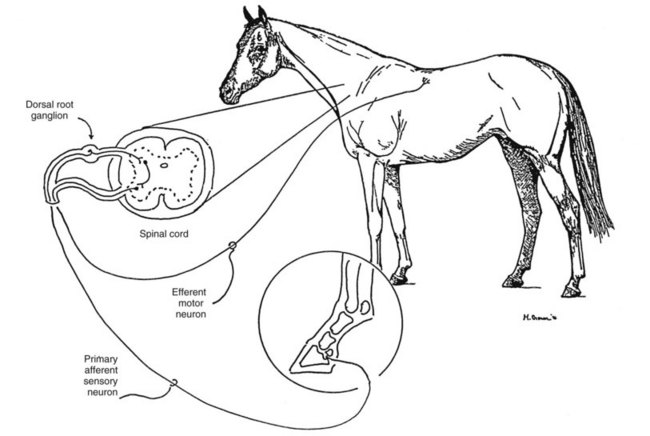

Acupuncture has many varied physiological effects on all systems throughout the body. No one mechanism can explain all the physiological effects observed. Traditional Chinese medical theories have explained these effects for 4000 years, based on empirical observations and descriptions of naturally occurring phenomena. Western medical theories include the gate and multiple gate theories, autonomic theories, humeral mechanisms, and bioelectric theories.10 Detailed discussions of the neurophysiological basis of acupuncture are reviewed in a number of texts.9-12 Essentially, acupuncture stimulates various sensory receptors (pain, thermal, pressure, and touch), which stimulate sensory afferent nerves, which transmit the signal through the central nervous system to the hypothalamic-pituitary system (Figure 92-2). The acupoints correlate with cutaneous areas containing higher concentrations of free sensory nerve endings, mast cells, lymphatics, capillaries, and venules. Various neurotransmitters and neurohormones are then released and have subsequent effects throughout the body. Research in rabbits using electroacupuncture-induced neural activation, detected by the use of manganese-enhanced functional magnetic resonance imaging, demonstrated a corresponding cerebral link between peripheral acupoints and central neural pathways. Research such as this is aiding in further understanding the effects of local peripheral stimulation on specific areas in the brain.13 Electroacupuncture has also been found to stimulate endogenous opioids, vasoactive peptides, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, cortisol, and catecholamine in cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral plasma in ponies.14 Bossut and colleagues15 documented changes in plasma cortisol and β-endorphin in horses subjected to electroacupuncture for cutaneous analgesia. Changes in serum protein and blood gas concentrations also have been demonstrated in donkeys after acupuncture.16,17 Xie and colleagues18 documented that electroacupuncture could relieve experimental pain in the horse via the release of β-endorphin. They found that acupuncture stimulation using local acupuncture points with high frequency (80 to 120 Hz) is more effective than using distal points with low frequency (20 Hz). They found that acupoints close to the painful areas require high-frequency electroacupuncture stimulation, whereas the acupoints far from the painful areas may be stimulated with low-frequency electroacupuncture. Electroacupuncture generally is considered to have stronger effects than other types of acupuncture methods.18 The degree of stimulation appears to depend on the location of the specific acupoints.19,20

Fig. 92-2 Cutaneous nerve entering the dermis at an acupuncture point along the bladder meridian.

(From Schoen AM, ed: Veterinary acupuncture: ancient art to modern medicine, ed 2, St Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

Through understanding the neurophysiology and neuroanatomy of acupuncture, one can appreciate that acupuncture may stimulate nerves, increase local microcirculation to joints and muscles, relieve muscle spasms, and cause a release of various neurotransmitters. Clinically, one may see the benefits of these effects in treating equine lameness caused by soft tissue injury, muscle spasms, nerve trauma, and other conditions.

Traditional Chinese Medical Theories

Acupuncture has been used in China to treat equine lameness for a few thousand years. Chinese acupuncture was based on the empirical use of acupoints for certain conditions. Historically, acupuncture meridians were not acknowledged in animals. Specific empirical points based on experience were identified and named for location or function. Equine acupuncture meridians, or pathways, have been transposed onto horses from human acupuncture maps only in the past 40 years.

Traditional Chinese medicine acupuncture diagnosis and treatment are based on the pattern differentiations that are developed from two main theories of traditional Chinese medicine: the Five Element theory and the Eight Principles, which require a great deal of study.21 The traditional Chinese medicine diagnosis is defined as a specific pattern based on imbalances in the five elements (also called five phases), imbalances and disorders in specific meridians or organs, or specific patterns of disharmony. The diagnosis is based on a physical examination of the horse, including evaluation of the tongue and pulse. Tongue inspection includes evaluation of the color of the tongue, the moistness, and the color and thickness of any tongue coating. Palpation of the jugular pulse would be described as weak, strong, wiry, and so on. Tongue and pulse examination and an overall examination would lead to a traditional Chinese medicine diagnosis and treatment of appropriate acupuncture points. Xie22 describes a traditional Chinese medicine five-step method for diagnosis and treatment. This includes the following:

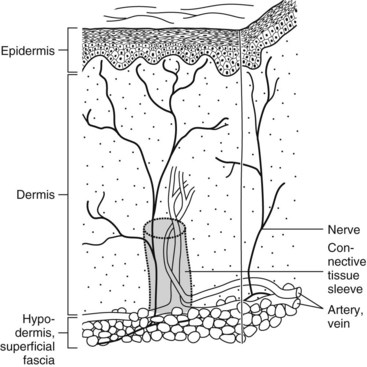

In contrast, the Japanese technique, frequently termed meridian therapy, is based more on palpation of the acupuncture points and the reaction. The anatomical location of equine acupoints is based on the traditional Chinese acupuncture atlases or a transpositional atlas based on transcribing human acupuncture points onto the equine anatomy. The location of the points is similar in each method, though anatomical variation exists, as discussed by Fleming23 (Figure 92-3).

Techniques and Instrumentation

Numerous techniques exist to stimulate acupuncture points. The following modes of stimulation are commonly used in equine acupuncture: dry needle stimulation, electroacupuncture, aquapuncture, moxibustion, laser stimulation, gold implants, and acupressure. Each method has its indications and limitations. Dry needle stimulation and aquapuncture are used most routinely in the West.

Aquapuncture is the injection of various solutions into the acupuncture points. The hypodermic needle is stimulating the acupuncture point as a traditional acupuncture needle would. In addition, the solution is stimulating the pressure receptors for a period, and the solution is having its specific effect as well. Solutions injected include saline, vitamins such as B12, nonsteroidal analgesics, local anesthetic solutions such as lidocaine, and occasionally homeopathic and herbal solutions, depending on the veterinarian’s preference. Electroacupuncture, using a portable electroacupuncture unit, normally is used for nerve stimulation to treat severe chronic cervical, thoracolumbar, or lumbosacral problems or an affected joint, tendon, or ligament. These electroacupuncture units have electrodes attached to the acupuncture needles. Positive results with electroacupuncture have been documented for treatment of lameness in horses. Electroacupuncture decreased the lameness score in horses (P < .001).24 Although poorly documented, electroacupuncture without needles is sometimes applied as well. Moxibustion is a form of thermostimulation using a Chinese herb, Artemisia vulgaris. Low-level or cold laser therapy is also used to stimulate acupuncture points. Gold implants have been used to treat navicular disease and chronic back pain and provide long-term stimulation of acupoints. This approach is an adaptation of the Chinese technique of sutures embedded into acupoints. Acupressure often is taught to the client to administer between acupuncture treatments to potentiate the effect. Detailed descriptions of these techniques are provided by Altman.25

From a Western medical perspective, acupuncture point selection is based on locating points on the body where stimulation produces a beneficial change in the central nervous system by modulating ongoing physiological activity, releasing local muscular spasms, and increasing local microcirculation. From a traditional Chinese medicine perspective, acupoints are selected based on a pattern differentiation developed from the Five Element theory or Eight Principles. The choice of acupoints based on the Eight Principles depends more on tongue and pulse findings and a comprehensive history. The Japanese approach to point selection follows a diagnostic acupuncture point examination, palpating diagnostic acupoints, including association (Shu) points on the dorsal aspect of the thoracolumbar region, alarm (Mu) points on the ventral aspect of the abdomen, and other diagnostic points. Many clinicians choose their points based on a combination of Chinese, Japanese, and Western diagnostic techniques, including tongue and pulse examination and diagnosis, diagnostic acupuncture point examination, sometimes including Ting points (points around the coronary band), and a comprehensive Western medical examination and history.26,27 The number of acupuncture points treated may vary from one to more than 20, depending on the condition treated and the approach and experience of the practitioner. The depth of needle insertion varies from 1 mm to 12 cm, depending on the location of the point, such as the coronary band versus dorsal lumbar musculature. The number of treatments required depends on the condition treated and the chronicity of the problem, usually ranging from one to eight treatments. The length of treatment varies from 5 to 30 minutes.

Manual therapies, such as chiropractic or osteopathy, are often applied along with acupuncture. They appear to work synergistically, acupuncture relieving muscle spasms and increasing circulation, chiropractic helping to correct skeletal fixations (see Chapter 93), and osteopathy affecting the fascia and skeletal structures (see Chapter 95). The combination of these therapies often leads to a more rapid response and greater efficacy, with fewer treatments required.

Clinical Applications in Lameness Examination and Treatment

Acupuncture Diagnostic Examination

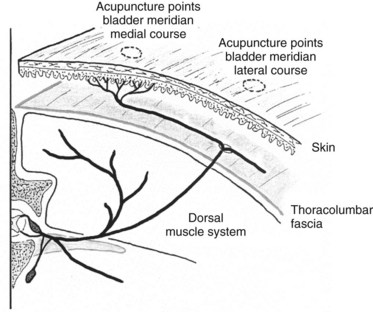

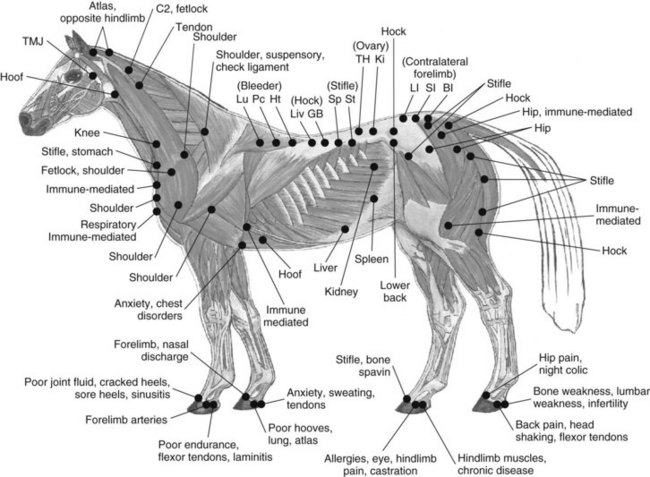

Acupuncture and manual therapies may be used diagnostically to aid in evaluating various lameness and performance problems. Acupuncture is an excellent diagnostic aid as an adjunct to a conventional lameness examination. Many of the diagnostic acupoints are located lateral to the dorsal midline, between the longissimus and iliocostalis muscles, along the acupuncture meridian known as the bladder meridian.26 In addition, some diagnostic points are actually trigger points, knots or tight bands in a muscle. For instance, a triceps trigger point is often sensitive to palpation when a distal forelimb lameness is present and correlates with the acupoint Small Intestine 9. A triceps trigger point may not indicate exactly where the lameness is or what the cause is, but it does indicate that something is reactive in that region (Figure 92-4).

Fig. 92-4 Diagnostic acupuncture palpation points.

(Courtesy Peg Fleming. From Schoen AM, ed: Veterinary acupuncture: ancient art to modern medicine, ed 2, St Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

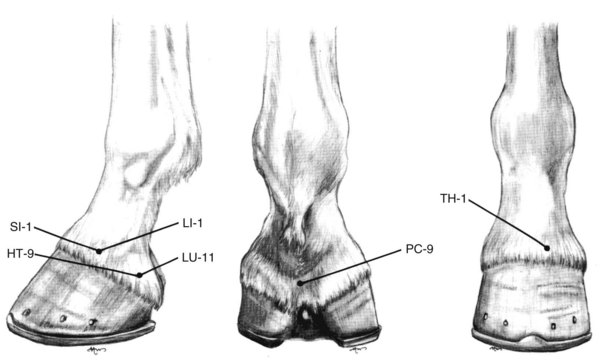

Diagnostic acupoints also are located around the coronary band on the forelimb and hindlimb, known as Ting points (Figure 92-5).15 Each diagnostic acupuncture point may have four or five meanings, depending on which other points show up as reactive on the examination. For instance, one point, Large Intestine 16 (located in a depression on the cranial border of the scapula, at the intersection of the cranial margin of the scapular muscles and the caudal margin of the brachiocephalicus muscle, cranioventral to the first thoracic vertebrae) may be reactive in horses with forelimb lameness, cervical conditions, or a contralateral hindlimb lameness.26 Sensitivity on acupoints along the bladder meridian, lateral to the dorsal midline, along the back may indicate that a hindlimb lameness is related to the stifle or hock, or that a primary back problem is related to the saddle fit, the rider, or a conformational problem. Sensitivity at acupoints suggesting a problem in the hock region also may be reactive with nearby injuries, such as a proximal suspensory problem. In addition, reactivity may indicate internal organ problems via a somatovisceral reflex. The combination of reactive points often aids the clinician in localizing the cause of the problem and determining a diagnosis. Often a horse may have a localized distal limb lameness along with a back problem. Sometimes acupoint diagnosis assists the veterinarian in figuring out which may have come first, the distal limb lameness or the back problem, based on the degree of sensitivity of the various points. Acupuncture diagnosis can be an excellent adjunct to conventional lameness examination, flexion tests, diagnostic analgesia, radiography, ultrasonography, and other diagnostic approaches. Not uncommonly we use all of our diagnostic capabilities, including nuclear scintigraphy and magnetic resonance imaging, and still do not arrive at a diagnosis. Acupuncture is often an excellent adjunct technique that may assist in elucidating the problem. In people, musculoskeletal pain often is accompanied by muscle shortening in peripheral and paraspinal muscles from spasms and contractures, and secondary trigger points and autonomic manifestations of neuropathies are also present in chronic musculoskeletal pain.28 Patterns of trigger points distant to the primary problem, compensating for the primary musculoskeletal problem, also have been found.29 These patterns are also evident in equine acupuncture lameness examinations. For instance, the horse may have a primary hock or stifle problem and may then develop compensatory patterns of trigger points in the back and neck and contralateral forelimb. These patterns show up as standard patterns of trigger points that may assist the veterinarian in the primary diagnosis.

Fig. 92-5 Ting points of the equine front foot. In a lateral position the points are SI-1 and HT-9; in a medial position the points are LI-1 and LU-11.

(From Schoen AM, ed: Veterinary acupuncture: ancient art to modern medicine, ed 2, St Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

An integrative approach to diagnosis is incorporated along with the acupuncture diagnostic palpation examination and includes evaluation of conformation, saddle fit, shoeing, and rider and training programs and the conventional lameness examination. Chiropractic evaluation, including static and motion palpation, also is included, which allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of all potential causes of lameness.

Acupuncture Therapy for Lameness

Acupuncture has been reported to be effective for treating various musculoskeletal pain–producing conditions and has been found to be beneficial in treating cervical, thoracolumbar, and lumbosacral hyperpathia,30,31 chronic back pain, chronic lameness, osteoarthritis, and colic. Hyperpathia, increased pain sensation detected as muscle spasms and increased sensitivity of acupuncture points, is often secondary to numerous causes, including work-related muscle soreness and injuries, metabolic diseases, infectious diseases, and underlying soft tissue and orthopedic problems. Wherever possible, primary underlying causes of lameness should be explored with appropriate diagnostic procedures. Conventional and complementary therapies should be considered based on what is most appropriate for the particular condition.

Back Pain

Chronic back pain can be a major cause of poor performance and may be caused by soft tissue damage or lesions to the thoracolumbar vertebrae. Numerous studies have documented the benefits of acupuncture for equine back pain.32-42

Xie and colleagues24 documented the success of electroacupuncture for treating chronic back pain in performance horses in a controlled clinical trial. They found that three electroacupuncture sessions were needed for clinical improvement. Conventional medical approaches, including the administration of muscle relaxants and analgesics, usually offer only temporary and minimal improvement, decreasing the clinical signs but not addressing the specific problems. Acupuncture is able to address specific muscle spasms and trigger points. Research suggests that electroacupuncture may be stronger and more effective than dry needle techniques or aquapuncture.24 Clinically, aquapuncture and dry needle techniques appear to be effective.

Pain Associated with Lameness of the Distal Aspect of the Limb

Acupuncture has been reported to be beneficial in horses with various distal limb lameness43-65 and has been beneficial in treating lameness related to the shoulder, elbow, carpus, tarsus, fetlock, stifle, hip, and numerous soft tissue injuries. In one study evaluating acupuncture in the treatment of distal limb lameness, Xie and co-workers24 found that electroacupuncture can partially relieve pain caused by the mechanical pressure induced by tightening a screw against the sole. They found that electroacupuncture significantly reduced the degree of lameness (P < 0.001). Electroacupuncture simultaneously increased plasma β-endorphin concentration, which suggests that endorphin release may be one of the pathways in which acupuncture relieves experimental pain. Electroacupuncture did not alter adrenocorticotrophic hormone concentrations, which indicates that the hormone may not be involved in this type of analgesia. This indicates that the mechanism of acupuncture analgesia is not merely a nerve block, as with local anesthetic solution, but that acupuncture analgesia also has central-acting effects. This correlates well with other clinical studies demonstrating the benefits of acupuncture in relieving equine lameness caused by joint contusion, muscular atrophy, rheumatic pain, and laminitis. Using a similar experimental design in a controlled clinical trial, Hackett and colleagues65 found that acupuncture alleviated equine pain, based on heart rate measurements as an indicator of pain response. In this study acupuncture was found to be more beneficial than nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications.

The experience of numerous clinicians suggests that acupuncture, combining local and distant points and using various techniques, can be beneficial as a primary or secondary modality. In clinical practice, acupuncture is beneficial in resolving chronic back pain. Establishing a primary cause of back pain is critical and includes evaluating the feet, saddle fit, rider, training, and conformation. If pain primarily is caused by conformation problems, long-term resolution may include periodic electroacupuncture, traditional acupuncture, or gold bead implantation.

Acupuncture and chiropractic are used successfully in treating various equine musculoskeletal conditions as primary treatments or as adjuncts to conventional veterinary therapeutic techniques. For instance, a horse may have primary distal hock joint pain and may be treated with an intraarticular injection. However, the injection may not completely resolve hock lameness. The horse may still “not be right” or may “be off.” Often secondary compensation and subsequent patterns of trigger points, muscular spasms in the longissimus, and vertebral fixations in the lumbar and cervical regions remain unresolved. Acupuncture and chiropractic therapy may then be used to treat the sequelae of the primary hock problem successfully. Hence the clinician then may resolve 100% of the lameness and increase client satisfaction.

Acupoint selection for lameness may include specific local points or ah shi (tender points) around a specific joint or region, points related to the secondary compensation for the primary lameness, and points based on traditional Chinese medicine or Japanese meridian therapy. Acupuncture may be used as primary therapy for distal limb lameness if conventional medical approaches have not demonstrated substantial improvement, or as an adjunct to conventional therapy. Horses with limb lameness that may benefit from acupuncture include those with laminitis; navicular disease; carpal, metacarpal, tarsal, fetlock, and pastern problems; soft tissue injuries; and some idiopathic problems. Horses with acute and chronic laminitis have responded favorably to acupuncture using dry needles, hemoacupuncture, or electroacupuncture. In the treatment of laminitis, local points around the coronary band are used along with distant points based on traditional Chinese medicine therapy.

Summary

Acupuncture can be beneficial in diagnosing and treating various lameness conditions, including distal limb and back problems. A thorough conventional diagnostic examination should be conducted along with an acupuncture diagnostic examination. All therapeutic options appropriate for a specific lameness condition should be considered. The advantages and disadvantages of each therapy should be discussed. Acupuncture can be considered as a primary therapy or as an adjunct treatment, depending on the condition. No one form of medicine has all the answers. Clinicians should consider the most appropriate conventional and complementary diagnostic and therapeutic modalities for the particular horse and its owner to develop a comprehensive, integrative approach to equine lameness. Acupuncture is one of these complementary approaches that may be beneficial for the lame horse.

Acupuncture Channel Palpation and Equine Musculoskeletal Pain

Acupuncture Channel Palpation and Equine Musculoskeletal Pain

The key to the diagnosis and treatment of equine musculoskeletal pain with acupuncture is the Oriental examination. The preferred use of acupuncture in a healthy, nonlame sports horse implies the anticipation and rectification of abnormalities before they become clinical entities. However, in the presence of overt pathology, the descriptive methodology and therapeutic protocol of acupuncture will proceed as in a presupposed normal horse. The basic principle of Traditional Oriental Medicine (TOM) as stated in Mandarin Chinese is bien jheng lun jhi, or in translation, “treatment is based on pattern differentiation.”1 The si jhun, or four examinations of (1) looking, (2) asking, (3) palpating, and (4) listening and smelling, are the criteria for determining patterns. A patient’s pattern is defined by the sum total of the signs, symptoms, tongue, and pulse as determined by the si jhun.2 Palpation is the most easily adapted of the four examinations for horses. In current equine practice the underpinning logic of TOM is combined with the precise palpation of the Japanese tradition and the linear analysis of Western equine lameness diagnosis.

How does the Oriental pattern-based therapy differ from the Western disease-based approach? The Western practitioner arrives at a diagnosis by physical examination supported by the available technologies such as nerve blocks, radiography, nuclear scintigraphy, and other techniques. The strict practitioner of TOM must rely on the patterns demonstrated by the horse using the si jhun without technical support. For example, in a horse with pain in the palmar aspect of a foot one might expect the following patterns, to name only a few: Blood Stasis, or fixed pain; Qi Stagnation, or moving, referred muscle pain; Liver Depression, or anger expressed in stereotypical behavior; and Heart Qi Vacuity, or anxiety. The total of the patterns is a description of the presentation of the disease in TOM. Most diseases exhibit a number of different patterns. Furthermore, therapy is defined by the pattern, because each pattern must be addressed in the subsequent therapeutic principles. In other words, the pattern of Blood Stasis (fixed pain) requires the use of a TOM therapy that will Quicken the Blood and Resolve Stasis. Qi Stagnation requires Moving Qi. The stated functions of each acupoint or herbal medicinal are used to determine which acupoints or medicinals to select. The proper use of the descriptive methodology of TOM forces a practitioner to describe each individual in terms of patterns that will then be used to determine therapy. None of this replaces Western structural diagnosis, but the scope of one’s physical examination is greatly enhanced.

One must evaluate the use of acupuncture by the elimination of abnormal pattern(s). However, any other therapy, be it Western or Oriental, can also be evaluated in terms of its effect on the pattern(s). For the purpose of practical illustration, consider that a horse with pain in the palmar aspect of the foot is not lame, but the rider complains of a change in performance caused by pain—for example, stiff in the corners, late leaving the ground when jumping, sore back. In such a horse the TOM pattern may add important information, whereas radiography, scintigraphy, and magnetic resonance imaging are technological overkill, expensive, unwieldy, and perhaps misleading. It may be less invasive and more efficient to treat the horse with available modalities such as shoeing, drugs, acupuncture, and herbs and to subsequently evaluate the change in pattern and performance. Sophisticated imaging techniques can and should be used to establish a structural anatomical diagnosis when possible. The therapeutic advantage of an integrated Western and Oriental approach is most applicable to a subclinically or functionally sore horse, as opposed to a horse with a structural lameness.

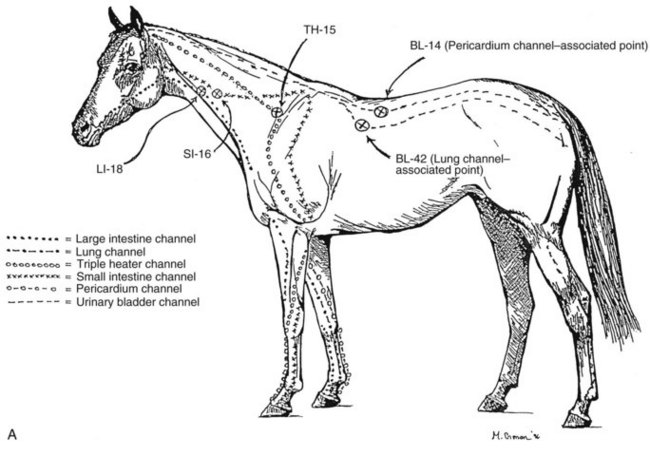

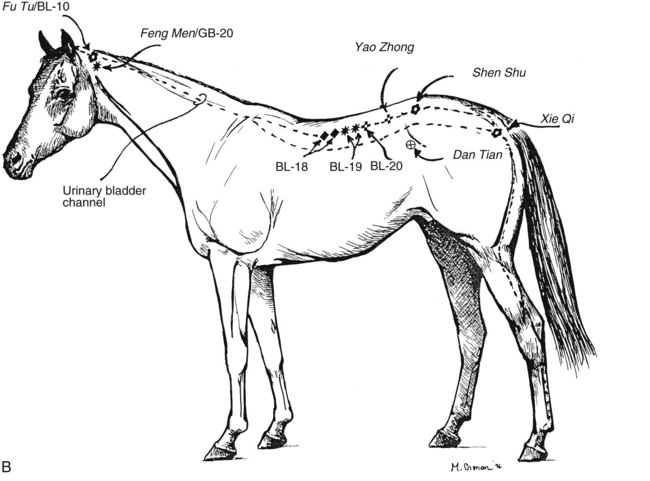

There is one examination within TOM that can be conducted in a timely manner and that can add information about every horse’s response to musculoskeletal pathology. Channel Diagnosis is a technique by which individual acupoints are palpated to determine the characteristics of those sites. Most acupoints are linked in groups called channels, which allow for a systematic organization. The acupoints themselves are specific anatomical sites on the body that a practitioner can use for diagnosis and treatment (Figure 92-6).3 Usually an acupoint is in a palpable depression in regions of high electrical conductance.4 Although there are 173 acupoints described in the traditional veterinary literature,5 less than 20 diagnostic acupoints are needed for the assessment of the response of the horse to exercise.

Fig. 92-6 A, The principal acupoints used in the diagnosis of channel pain referable to the equine forelimb. B, The principal acupoints used in the diagnosis of channel pain referable to the equine hindlimb.

(Courtesy William E. Jones.)

The qualitative acupoint description attained through palpation can be useful in a Western context. Acupoint examination should include a grading system for reactivity and a recording of those reactions over time. I use the following simple grading system for acupoints in Excess. As opposed to the characteristic of Deficiency, acupoints in Excess are the easiest to appreciate and locate, because they are actively sensitive and energetically rise to meet the examiner’s palpation. The grading scheme is as follows: Grade I is a normal, supple, and nonpainful response to deep (1 to 5 cm) palpation. Grade II is a slight muscle twinge that is fatigable. Grade III is consistent pain or avoidance response to deep palpation. Palpation of an acupoint with Grade IV sensitivity will elicit a sharp avoidance response accompanied by a kick or a bite. Sensitivity of Grades III and IV are of sufficient severity to warrant therapy.

The Deficiency pattern is the mirror image of the Excess pattern. Whereas the Excess pattern reflects the superficial response of the organism to adversity, the Deficiency pattern reflects a more subtle depth of pathology.6 Unfortunately, the determination of the presence of a Deficiency pattern requires the clinician to recognize the horse’s minimal passive resistance to palpation. The Deficiency pattern can best be appreciated after the practitioner has injected intraarticular antiinflammatory medication in a degenerative joint. In such a horse the Excess pattern of muscle hyperreactivity related to the joint will be dramatically dissipated, but there will remain a low resistance that can easily be missed in superficial palpation. The sharper the Excess perceived by the examiner the greater the probability of the presence of underlying, hidden Deficiency. The difference between these two patterns in sports horses is theorized to be caused by the difference in reflex muscle tension caused by synovial receptors (Excess) and extrasynovial structures (Deficiency). A nonarticular example of extreme Excess and Deficiency patterns in the horse occurring simultaneously would be that of tying-up, in which the “boardlike” quality of the superficial muscles prevents any deep palpation of Deficiency in the underlying structurally affected tissues.

Each of the following acupoints corresponds to a TOM channel or meridian, which in turn is named after an internal organ. The twelve channels govern the flow of Qi, or life forces, for the whole body. I mix TOM acupoints with International Veterinary Acupuncture Society (IVAS) transpositional points to give the best overall assessment of a horse (Box 92-1).

BOX 92-1 Traditional Oriental Medicine Acupoints and International Veterinary Acupuncture Transpositional Points for Best Overall Assessment of a Horse

What meaning can we attribute to reactive acupoints? I published a series of articles on the use of reactive acupoints in Excess for pain referable to the shoulder joint,12 metacarpophalangeal joint,13 distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint,14 and the joints of the distal aspect of the hindlimb.15 These articles were based on 712 lame and “sore” horses. Over 14 years, which succeeded 13 years of strictly Western lameness practice, many thousands of examinations were conducted to establish a protocol and to subsequently confirm the principles for evaluating reactive acupoints. In another study 350 working sports horses and racehorses were represented as serviceably sound, but 37% of the horses were lame and 39% had reactive acupoints.16 When the lame horses were compared with the sound horses with respect to reactive acupoints, 25% of the sound horses had Grade III or IV reactive acupoints, whereas 63% of lame horses had similar abnormalities.16 Therefore, reactive acupoints in the channels were frequently observed and bore a close relationship to lameness and, by implication, a similar relationship to subclinical musculoskeletal pain.

The following is a set of guidelines for palpating acupoints in Excess:

When a horse with subclinical pain but with a multipattern acupoint abnormality is examined, intraarticular medication may remove one or more patterns. If a horse has acupoint examination abnormalities reflecting the extremities of both the forelimbs and hindlimbs and the distal hock joints are injected, and if, indeed, the primary source of inflammation is the tarsus, then the whole acupuncture presentation will change. But if there is concomitant involvement of the hind fetlock, stifle, or forelimb joints, then only the pattern reflecting the distal aspect of the tarsus will change. The patterns that reflect the other joints will remain the same. Nonarticular peritarsal pathology such as painful hind splints or suspensory desmopathy will not directly cause a pattern that is reflected in reactive acupoints in Excess. Rather, the Excess pattern will reflect only the distal aspect of the tarsus. Joint infection is also not reflected in Excess acupoints.

It is good practice to routinely reexamine horses that have received joint therapy or acupuncture on both day 1 and day 7. Reexamination allows for a rider or trainer’s evaluation as well as a careful reassessment by the veterinarian. If the pattern is balanced and the horse is doing well, then one’s efforts should be directed toward maintaining the acupuncture balance. The remaining points of low reactivity can be managed using acupuncture or manual therapy. However, if lameness or sharply reactive acupoints remain, then the basic premise of one’s diagnosis must be reevaluated.

The effect of other medications and management changes can be assessed. Shoeing changes will directly affect acupuncture balance, as will the forgiveness of track surfaces and training and management regimens. It is the responsibility of the trainer to bring the equine athlete up to the peak of fitness without going over the edge. The acupuncture examination is one of the ways that “the edge” can be defined. From the Western point of view, the presence of acupoints in Excess in musculoskeletal conditions indicates that affected joints have not been able to spontaneously recover from exercise-induced hyperflexion. Excess acupoint reactivity in joint pain is a function of highly innervated intraarticular synovial structures that are activated by the mediators of traumatic inflammation,21 which in turn are activated by joint hyperextension. The distribution, incidence, and severity of Excess acupoint activity depend on the spatial distribution of nociceptor sites within specific joints and the quantity and characteristics of released inflammatory mediators within those joints. Lameness is a function of a much broader range of pain perception.

Joints that project reactive acupoints vary according to the horse’s use. Thoroughbred racehorses have a greater incidence of synovial inflammation in the metacarpophalangeal joint, reflecting the proximal dorsal aspect of the proximal phalanx versus the DIP joint, whereas the converse is true for show hunters. In both types of horses I find a high incidence of distal hock joint pain. Steeplechase horses and show jumpers have a high incidence of hind fetlock inflammation, and numerous ipsilateral joints can be involved. It is difficult to determine multiple joint inflammation if lameness is not severe enough to abolish using diagnostic analgesia. Careful examination of horses after joint therapy and over time should reveal changes in acupoint reactivity. Horses returning to competition after a long rest tend to revert to the same acupuncture patterns that they displayed during previous training. In horses recovering from surgery, the acupuncture pattern is a sensitive early sign of a need for changes in management.

Two papers published in English define the limits of acupuncture in sports horses. Martin and Klide’s work on back pain showed the efficacy of modulation of muscle tension on the performance of equine athletes.22 Steiss showed that acupuncture in foot lameness was no better than that expected in untreated controls.23 Martin and Klide were treating the TOM pattern of Qi Stagnation or abnormal muscle tension as opposed to Steiss’s fixed pain pattern of Blood Stasis. The strength of acupuncture is its ability to restore normal physiological activity in the face of functional abnormality. Hackett, Spitzfaden, and May showed that pain modulation after digital electroacupuncture is similar to that provided by phenylbutazone therapy.24 However, foot pain cannot be as easily reversed as abnormal back muscle tension. Acupuncture can be used effectively as an adjunctive therapy if muscle hyperactivity is part of the pattern. Careful examination of the channels should provide evidence of patterns with a good therapeutic potential.

The basis of acupuncture diagnosis and therapy in musculoskeletal disease depends on pattern differentiation. The patterns most easily determined by the Western practitioner involve the precise palpation of key acupoints in Channel Diagnosis. Acupoint reactivity of musculoskeletal dysfunction is a reflection of the body’s response to intraarticular trauma. Because only highly innervated synovial structures of a small number of joints of the extremities are reflected by reactive acupoints, the primary disease may be reflected only indirectly or not at all. However, abnormal patterns are extremely common and are worth investigating regardless of the type of therapy contemplated. At the least, the abnormal pattern is a warning. The ease that one has in elimination of a pattern over time will give an idea of the persistence and severity of the underlying traumatic pathology.

The pattern projected by synovial structures is a protective mechanism, the presence of which is the teleological function of limitation of joint excursion. Therefore, effective treatment must go beyond the elimination of acupoint imbalance and address all the underlying problems as well. Because disease in TOM consists of all of the existent abnormal patterns, treatment of multipattern abnormalities must be undertaken. In my experience the channel approach to horses with subclinical pain is effective and useful. With the exception of lameness from muscle tension, acupuncture is generally not sufficient by itself to address lameness that is obvious enough to abolish using diagnostic analgesia.