Chapter 112National Hunt Racehorse, Point to Point Horse, and Timber Racing Horse

Description of the Sport

For as long as horses have been domesticated and ridden, they have been raced. The oldest record of racing in Britain shows that the Romans used to race their horses in Chester. Subsequently, little is known about any organized horse racing during the Middle Ages, but by about 1150 racing had become established at Smithfield, a horse market, where horses were tried and sometimes raced before sale. By the early part of the sixteenth century, racing had returned to Chester, where the prize for the winner in 1511 was a silver bell.

All of these races were on turf with no obstacles to negotiate. At about the same time that horses were competing for the Chester bell, fox hunting (rather than hunting deer or wild boar) started to become established and rapidly increased in popularity. One reason for this may have been the changing agricultural landscape as more and more land was enclosed, providing natural obstacles for those following the hunt to jump. Inevitably, rivalry developed among those who regularly followed fox hunts across country regarding who had the fastest horse, and a new sport was born, known as steeplechasing. The origin of the name is simple. Because no courses were defined over which the races could take place, the participants had to race from one church to another, using the high church steeple toward which they were heading as a landmark. The riders could choose their own route and had to jump a variety of fences such as hedges, banks, walls, timber fences, and brooks during the course of the race. The first steeplechase of this type was held in Buttevant in Ireland in 1752, when two neighbors raced between Buttevant church and the St Leger church, a distance of  miles (7.2 km).

miles (7.2 km).

Eventually this new sport was formalized, with specially constructed courses that allowed more participants to take part and more spectators to watch. The first such organized race meeting in Britain was held at St Albans in 1830. The Grand National was first staged in 1839, the National Hunt Steeplechase followed at Market Harborough in 1859, and the first meeting at Cheltenham (Prestbury Park), arguably the best known modern jump racing venue, was in 1898.

As the sport developed, regulating it became important, but the Jockey Club, which had been regulating flat racing since the mid-eighteenth century, regarded the new sport with suspicion. Accordingly, a separate National Hunt Committee was established in 1866 and continued to run jump racing until 1969, when it and the Jockey Club merged to bring all racing, on the flat and over jumps, in Britain under one governing body. The National Steeplechase Association oversees racing over fences in the United States.

Modern National Hunt racing now consists of several categories, all run on turf on clockwise and counterclockwise courses. Horses run under similar rules in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and France. Elsewhere in Europe, racing over fences takes place but on a much lower scale. Most races are hurdle races or steeplechases, but some races run over more natural obstacles remain—some that are run over exclusively timber fences, and some, called National Hunt flat races, that are run without obstacles.

Apart from the fences, three major differences exist between National Hunt and flat racing, which are important in the epidemiology of the injuries that may occur in the different sports. These differences are the race distance, the age of the horses, and the weights of the riders. All National Hunt races are more than a minimum of 2 miles (3.2 km) compared with the minimum distance of 5 furlongs (1 km) on the flat, and the horses are at least 3 years of age. Forty percent of National Hunt Flat races involve horses of 4 years of age, a slightly higher percentage are 5 years of age, and less than 20% are 6 years of age or older. Most horses competing in flat races are 2 or 3 years old, but it is not unusual for horses over the age of 10 to race in National Hunt races, especially in steeplechases. Finally, National Hunt horses carry 10 stone (63.5 kg) to 11 stone 12 lb (75.3 kg), considerably more weight than flat horses.

Hurdle races are held over fences smaller than those encountered in steeplechasing. In Britain, most hurdles are derived from the simple portable fences used to create temporary pens for sheep, although small brush hurdles are being trialed. They are usually 72 inches (1.83 m) wide and must be not less than 42 inches (107 cm) from top to bottom bar and constructed of ash or occasionally oak. Several hurdle sections are placed end to end to produce an obstacle that must be at least 30 feet (9 m) wide. Each hurdle section consists of two uprights with pointed legs that are driven into the ground and five horizontal rails, between which is interwoven birch or another suitable material. Gorse, which is durable but has sharp thorns, is not permitted. The hurdles must be driven into the ground at an angle of 62 degrees so that the top bar is set back 20 inches (51 cm) from the vertical, and the effective height of the hurdle is 37 inches (94 cm). All of the exposed timber parts must be padded with a minimum of  inch (1.3 cm) of high-density polyethylene or closed cell foam rubber (Figure 112-1).

inch (1.3 cm) of high-density polyethylene or closed cell foam rubber (Figure 112-1).

Fig. 112-1 A hurdle race. The jump of the leading horse, which has almost run through the hurdle, is awkward, the hindlimbs are positioned asymmetrically, and the horse’s back is hollow.

Timber hurdles have the advantage that if a horse misjudges the fence and does not jump it cleanly, the hurdle gives way on impact. Old style hurdles were not padded as well as the modern versions and occasionally led to lacerations on the dorsal aspects of the hindlimbs, which could be extensive with degloving injuries of much of the metatarsal region. These injuries have been virtually abolished by the new padding.

In countries other than Britain and Ireland, timber hurdles are replaced by fences that look like small versions of steeplechase fences. Such fences also are seen on a small number of racecourses in Britain, and proponents of these types of fences argue that they provide a better introduction to racing over obstacles for horses that ultimately are intended to be steeplechasers. This may be true, but only 35% of horses that run over hurdles convert to steeplechasing, indicating that hurdle racing has become a specialty sport that draws many of its participants from horses that have raced previously on the flat.

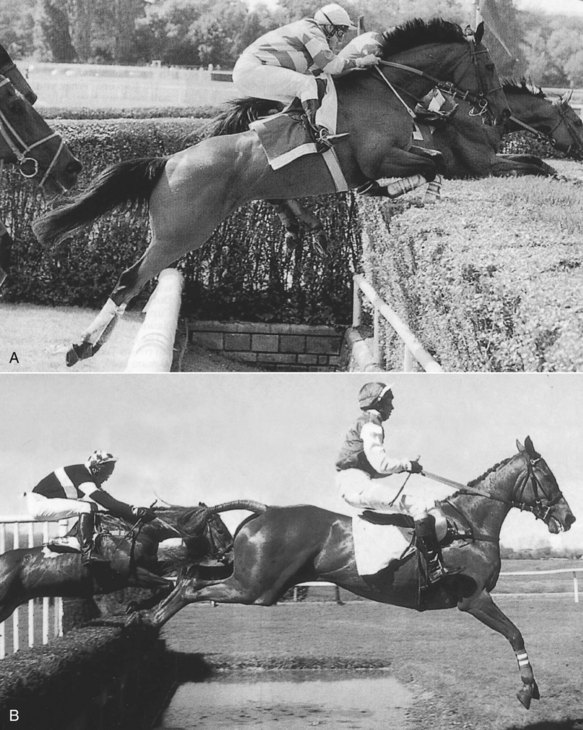

Steeplechases are run from 2 to  miles (3 to 7 km) over fences that, with the exception of those at Aintree, over which the Grand National is held, have a standard construction. The course must have at least six fences per mile, one of which must be an open ditch, with the other plain fences. The plain fences must be a minimum of 54 inches high (1.37 m) and constructed of birch, or birch and spruce, in a frame. The use of gorse is not permitted. The base of the fence must be 72 inches (1.83 m) from front to back, with the thickness of the fence at its top not less than 18 inches (46 cm) (Figure 112-2, A). Plain fences usually have a guard rail on the face of the fence that usually is padded with the same material as the hurdles. An open ditch has similar overall dimensions, but the ditch in front of the fence, which may or may not be dug out, must be at least 72 inches (183 cm) from front to back and be delineated by a takeoff board that is up to 24 inches high (146 cm). Designers of racecourses also, if they wish, may include a water jump in steeplechases. These consist of a smaller fence, up to 36 inches (91 cm) high, with a 108-inch (2.74-m)–wide water ditch, which must be 3 inches (7.6 cm) deep, on the landing side of the fence.

miles (3 to 7 km) over fences that, with the exception of those at Aintree, over which the Grand National is held, have a standard construction. The course must have at least six fences per mile, one of which must be an open ditch, with the other plain fences. The plain fences must be a minimum of 54 inches high (1.37 m) and constructed of birch, or birch and spruce, in a frame. The use of gorse is not permitted. The base of the fence must be 72 inches (1.83 m) from front to back, with the thickness of the fence at its top not less than 18 inches (46 cm) (Figure 112-2, A). Plain fences usually have a guard rail on the face of the fence that usually is padded with the same material as the hurdles. An open ditch has similar overall dimensions, but the ditch in front of the fence, which may or may not be dug out, must be at least 72 inches (183 cm) from front to back and be delineated by a takeoff board that is up to 24 inches high (146 cm). Designers of racecourses also, if they wish, may include a water jump in steeplechases. These consist of a smaller fence, up to 36 inches (91 cm) high, with a 108-inch (2.74-m)–wide water ditch, which must be 3 inches (7.6 cm) deep, on the landing side of the fence.

Fig. 112-2 A, A steeplechase race in France. B, A point to point race. The fences are smaller than in steeplechase races, and the amateur jockeys tend to be less well positioned.

Point to point races (see Figure 112-2, B), named because originally they were run from one point to another, represent the amateur branch of steeplechasing and are restricted to horses that have qualified to race by hunting with a registered pack of hounds. Races for such horses also take place on licensed racecourses and are known as Hunters’ Steeplechases (or Hunter chases).

Some races, notably in France, at Punchestown in Ireland, and at Cheltenham in Britain, are run over more natural obstacles, including banks and growing hedges. Timber races are held over upright (United States) or sloping (Britain) post and rail fences (Figure 112-3). To make the obstacles less dangerous, the top rails may be sawn through so that they will knock down if they are hit hard.

Finally, National Hunt flat races are staged for horses that have not run previously on the flat and are at least 3 years old. The races are intended to teach horses to acclimatize to the environment of a racecourse and the rigors of a race, without the additional hazard of obstacles. They also provide a way of demonstrating a horse’s ability so that it can be sold. Colloquially, National Hunt flat races are known as “bumpers,” because originally they were restricted to amateur riders, and the combination of inexperienced riders and horses led to their pejorative nickname.

National Hunt Horses

British and Irish National Hunt horses may be Thoroughbreds, which are registered in the General Stud Book, or non-Thoroughbreds, which are in the Non-Thoroughbred register. Many top-quality French jumping horses are of the Selle Français breed. Horses are started in jump racing by one of two routes. They are raced on the flat at 2 or 3 years of age before moving on to hurdling and possibly to steeplechasing, or they are bred specifically for National Hunt racing. Red Rum, who won the Grand National on three occasions, is an example of a horse that started racing in flat races as a 2-year-old. In general, however, horses that graduate from the flat tend to stay in hurdle races, and only 35% of horses that race over hurdles go on to race in steeplechases. Geldings tend to predominate in both types of race.

Steeplechasers tend to be bred for that particular type of racing and are usually bigger-framed Thoroughbreds compared with flat racehorses. Breeding steeplechasers is less straightforward than breeding for flat races, because most steeplechasers are geldings, meaning that it is unlikely that males can be chosen based on racecourse performance. Finding performance-tested mares also is difficult, because the average age of steeplechasers is the highest of all racing categories, and by the time a mare has proved her ability, she may be past her breeding prime. Therefore most stallions that are popular as sires of steeplechasers are horses that have shown stamina on the flat and then prove to sire successful progeny. Many mares that are used to breed steeplechasers are chosen because of pedigree rather than performance.

Once foaled, many horses destined for steeplechasing are left unbroken until 3 or 4 years of age, when they are often sold as National Hunt stores (horses bred specifically for National Hunt racing) intended to start a racing career at 4 or 5 years of age. This traditional system has been used for many years and could be said to have stood the test of time. Recently, National Hunt breeze-up sales have been introduced and are gaining in popularity. However, some research suggests that horses benefit from an early introduction to regular exercise and from early racecourse experience, and this may reduce the risks of injury.1 Moreover, the later that horses enter training, the higher the risk of fatal injury.

Training National Hunt Horses

At its simplest, training involves conditioning the cardiovascular, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems of horses to tolerate maximal exercise. The skill of the trainer is to exert the horse sufficiently to achieve this while avoiding physical injury and without inducing an aversion to hard work. Human athletes, being motivated to succeed, tolerate extreme discomfort during training to achieve their goals. Horses have to be encouraged to exercise and never to anticipate that the result of exercise will be discomfort or pain.

Horses that move to National Hunt racing from flat racing receive the basic conditioning as yearlings and young 2-year-olds. Store horses, however, may do little regular exercise until they are virtually skeletally mature at 4 years. Because they are older, thinking that they require less time to adapt to exercise is tempting, whereas the reverse may be true. It is therefore essential that early preparation is graduated gently and that early signs of failure to adapt, such as sore shins or joint effusions, are noted and training intensity adjusted. If clinical signs go unrecognized or ignored, more serious skeletal defects may develop, such as stress fractures of the tibia, humerus, or pelvis, which may precede catastrophic fractures on the gallops or racecourse. Traditionally, store horses spent at least 6 weeks walking and trotting on quiet roads and tracks before they commenced any faster work. This initial slow preparation has now been abandoned by many trainers, partly because of the difficulty of finding a suitable safe, quiet environment and partly because of the economic pressure to see the horse on the racecourse.

Most trainers of National Hunt horses now use a simple adaptation of interval training over distances of about 1000 m, almost invariably up an incline that may be steep. An average morning workout would be an initial slow warm-up, followed by two brisk canters up the incline on an easy morning, alternating with three faster ascents on a work morning.

One of the most important aspects of training National Hunt horses is teaching them to jump appropriately. Hurdle races are conducted at a fast pace, and some trainers believe that horses that jump the obstacles without touching them, and with the same action as a show jumper, use energy unnecessarily and concede ground to rivals who jump low and flat. This is possible because the timber hurdles give way if the horse hits them, although the ease with which they do this depends on the ground into which the legs of the hurdles have been driven. Once horses have acquired this style of jumping, some trainers argue that the horse finds it difficult to jump the larger, more solid, steeplechase fences. This accounts for the relatively low number of horses that make the transition from hurdling to steeplechasing and the demand in Britain by some trainers for a brush hurdle that, although relatively small, has to be jumped with care. Specialist steeplechasers are encouraged to jump much as horses intended for other disciplines that involve jumping, and they jump low poles and logs, with and without a rider, before progressing to larger obstacles. However, the amount of training carried out over fences by steeplechasers is proportionately much less in the United Kingdom and Ireland than for event horses or show jumpers.

Racing National Hunt Horses

Jump racing developed as a winter sport, probably originally because of the connection with fox hunting, which also is conducted during the winter months. However, jump racing is now held in Britain throughout the year, although those courses that hold summer jump meetings are required to ensure by artificial irrigation that the ground conditions are kept no worse than good to firm. This is because epidemiological studies have shown that firm ground conditions are more likely to be associated with serious injuries. The reason for such a relationship is complex. It is probably related to the speed at which the horses travel, but other complex factors influence the interaction of the horse’s foot with the ground under various conditions, some of which are related to ground hardness, and these require further research and elucidation. Jump racing remains seasonal, however, because the major races take place from November to March, and many horses spend a few weeks turned out during the summer. Seasonal racing influences injury management, because if a horse sustains a clinically significant injury in, for example, late February, the owner or trainer applies pressure for the horse to be ready for the next season—that is, to resume training by October of the same year.

Horses are trained by individual trainers spread throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland, and France and may travel long distances to compete. Therefore any single veterinary surgeon usually does not deal with more than four or five trainers and their horses. At race meetings the horses are subjected to prerace veterinary inspections, and each race is monitored carefully by veterinary surgeons driving on the outside of the track alongside the race and a veterinarian observing the entire race from an appropriate vantage point.

Point to point races are held from January to June. Point to point racing is an amateur sport, raced over obstacles that are smaller and softer versions of the steeplechase fences on licensed racecourses. Some horses that perform well in point to points successfully graduate to steeplechasing, and this route to steeplechasing is chosen by some owners in preference to hurdle racing, possibly after one or more National Hunt flat races. While National Hunt horses run on average between four and five times per year, point to point horses may run more frequently during the season, because the race meetings are usually held at weekends. However, the average number of starts per point to point horse in 2000 was only three.

Because of the two distinct sources of horses that enter National Hunt racing, a wide variety of injuries is seen, ranging from injuries related to beginning training to degenerative injuries associated with overuse. In addition to the injuries sustained while the horse is in training, a National Hunt horse is more prone to injury after a fall than is a flat racehorse (Figure 112-4). It is also important to be aware that horses that are skeletally mature when they begin training (4- to 5-year-old store horses) still undergo the same pathophysiological processes that lead to stress fractures, albeit in different sites from the 2- or 3-year-old Thoroughbred. Because National Hunt racing continues throughout the year, the going under foot (footing) can vary, and extremes of both soft and firm going place the National Hunt horse under extra stress from injury.

A substantially higher death rate occurs in National Hunt racing compared with flat racing.1-7 In a retrospective analysis of data from all starts from January 1990 to December 1999, 2015 deaths were recorded on racecourses from 719,099 starts.1 The death rate per 1000 starts was substantially higher in steeplechasers (6.7; 34.5% of the total) and hurdlers (4.0; 43.4% of the total) compared with flat racehorses (0.9; 18.8% of the total). Spinal injuries occur much more frequently in hurdlers (19% of all hurdler deaths) and steeplechasers (23% of steeplechaser deaths) compared with flat racehorses (1% of flat racehorse deaths). Tendon breakdown injuries resulting in humane destruction at the racecourse were also substantially higher in hurdlers (20% of hurdler deaths) and steeplechasers (14% of all steeplechaser deaths) compared with flat racehorses (8% of flat racehorse deaths). Risk of mortality was associated with a number of variables. With steeplechase horses a higher risk occurred in horses that started steeplechase racing at 8 years of age or older. The weight carried was also influential, with horses carrying more than 70 kg minimum weight being at greater risk. Races longer than 4 miles were associated with a higher risk than shorter races. Heavy going, resulting generally in slower speeds, reduced the risk. Good to firm or hard going increased the risk of mortality in hurdlers and steeplechasers.

Timber Racing

Timber racing is considerably more popular in the United States than in the United Kingdom and is more structured. Novice or stakes horses compete only against one another, with greater prize money for stakes races, the most valuable being the Maryland Hunt Cup. The most prestigious race in the United Kingdom is the Marlborough Hunt Cup. Historically the stakes races with the largest amounts of prize money have been open only to amateur jockeys; however, recent rule changes have allowed for professionals to ride in these races in the United States. Timber racing horses often have raced previously on the flat or over hurdles, are usually 6 to 12 years of age, and may have injuries from earlier racing, particularly osteoarthritis (OA) of numerous joints and stable superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) injuries.

Track Surface or Training Surface and Lameness

The surfaces and terrain over which horses train vary extremely because the trainers are dispersed widely geographically. Much of the work is done on grass, but fast work often is done on all-weather purpose-built gallops. Many horses hack up to a mile to and from the gallops, ensuring good warm-up and cool-down. However, the standard of maintenance of the gallops varies. Poor gallops with an inconsistent surface varying from soft to deep may increase the risk of tendon injuries or predispose horses to stumbling and accidents such as third carpal bone fractures. Many trainers are based in areas of chalk downland (natural rolling hills with a chalk subsoil), which drains well, but the large number of flints (sharp stones) in the soil may result in a high incidence of bruised soles or sole punctures unless the horses have well-conformed feet. The steepness of the terrain over which the horses do fast work may influence injury. An increased number of pelvic fractures was noted after a new gallop was laid, the last section of which was up a steep incline (RvP). In a yard of 40 horses, one or two horses per year sustained pelvic or tibial stress fractures, but after the new gallop there were seven ilial wing fractures (three right, four left), two sacroiliac subluxations (one bilateral, one right), and two tibial stress fractures. These injuries may have been caused by hind foot slippage. After the gallop was recontoured, the problem resolved.

The influence of falls on the nature of injuries is substantial.2-7 Most falls occur on landing over a fence. Falls may result from the horse or jockey making a jumping error, from interference by another horse still in the race, or from a loose horse that had previously unseated its rider. The fall of one horse may result in the fall of one or more other horses (Figure 112-5). Thus injuries may result from the fall and impact with other horses. Falls may result in fatal fractures of the cervical or thoracolumbar vertebrae. Rib fractures usually result from a fall and may cause severe lameness and/or respiratory signs. Other fractures seen commonly, usually resulting from a fall, include scapular, radial, and humeral fractures; fractures of the accessory carpal bone; and fractures of the lateral malleolus of the tibia. Major muscle ruptures, especially in the hindlimbs (e.g., semimembranosus, quadriceps, or adductor) also usually result from a fall. Rupture of the fibularis tertius may occur if the horse falls with forced hyperextension of the hock.

A significant statistical correlation exists between certain factors and the incidence of injury on racetracks:

miles with only a few obstacles (six to eight), the casualty rate increases compared with the same distance with nine or more fences.

miles with only a few obstacles (six to eight), the casualty rate increases compared with the same distance with nine or more fences.Digital flexor tendon lacerations frequently are sustained as horses race over fences and generally occur on the palmar aspect of the metacarpal region, proximal to the proximal sesamoid bones (PSBs). It is important to recognize that the site of a skin laceration may not coincide with the site of a tendon laceration.

Some important injuries occur more commonly during racing than training. Luxation of the SDFT from the tuber calcanei sometimes occurs. Rupture of the musculotendonous junction of the superficial digital flexor (SDF) muscle is an unusual injury, but is an important injury in steeplechasers. SDF tendonitis is common in National Hunt horses,5-7 and recurrent injuries may result in complete rupture of the tendon.

Conformation and Lameness

With an increasing proportion of National Hunt horses starting training earlier and running first on the flat at 3 years of age and then over hurdles at 4 years of age, the trend has been toward using smaller, lighter-framed horses. Although such horses are not necessarily more prone to injury, they seem less able to cope with deep, holding going often encountered in the winter months compared with the more traditionally bred rangy National Hunt store horses, which are often rather late maturing.

For a National Hunt steeplechaser or hurdler to race until 10 years of age is not uncommon, so the racing career is considerably longer than for a European flat racehorse. Horses should be well balanced and proportioned, with good feet and adequate bone for body size and weight. Horses with back-at-the-knee conformation, carpus valgus, offset knees, or substantial toed-in or toed-out conformation particularly may be predisposed to forelimb problems. A long back may be associated with an increased risk of back problems. A horse with straight hocks or long, sloping hind pasterns may have an increased risk of hindlimb lameness.

In a study evaluating variation in conformation in a cohort of National Hunt horses, Thoroughbreds were found to be different from other breeds in lengths, joint angles, and deviations, but variation was small.8 In a group of 108 National Hunt horses an increase in intermandibular width, flexor angle of the shoulder joint, and coxal angle (angle between the ilium and ischium) had a positive effect on race performance.9 Performance decreased with increases in girth width and hind digit length and with valgus conformation of the metacarpophalangeal joint, and the risk of superficial digital flexor tendonitis increased with increased metacarpophalangeal joint angle and carpus valgus limb deformity.9 The risk of pelvic fracture decreased with an increase in coxal angle, but risk increased with greater tarsus valgus limb deformity.9

Lameness Examination

Diagnosis of lameness starts with a full history, which should include stage of training, because, for example, a 6-year-old store horse starting training is as susceptible to stress fractures as an immature athlete. The clinician should establish whether the horse has run recently. Is the lameness of recent onset, or is it a chronic problem that has been getting progressively worse? Some trainers request advice as soon as lameness is recognized, whereas others may restrict the horse to light work and seek veterinary advice only if lameness persists. Some trainers treat a lame horse with phenylbutazone. Many trainers are happy for horses to come out rather short, shuffly, and stiff and warm up to move more freely; however, more overt lameness usually supervenes, or a back problem develops secondarily.

It is important to determine if the horse has had any time off recently with the present trainer or a previous trainer that may suggest a previous injury. There may be a history of warmth associated with the palmar metacarpal region that, if the horse has been subsequently rested, may not be obvious on clinical examination. Does the horse have any history of trauma? Jumping history is also important: did the injury occur while the horse was schooling over fences or in a race? Did the horse fall or collide with another horse (Figure 112-6)? Does the lameness resolve with rest or does the horse warm out of lameness?

Fig. 112-6 A fall at the Chair at the Grand National. The horse pitches steeply and lands on its neck.

If the horse had a history of a fall, it is important to establish how the horse fell. It may be possible to review video footage. Did the horse turn a full somersault, land on its pelvis, and develop lameness thereafter? A pelvic injury should be suspected. Did the horse fall at the end of a 3-mile race on heavy going and lay winded? Information from the racecourse veterinarian may be particularly useful.

If a horse has a history of poor jumping performance, trying to establish if the horse has ever been a good jumper over hurdles or fences is worthwhile. Many of these horses are lame. The veterinarian needs to find out how the horse is jumping. Does the horse stand off the fences or jump flat? If a horse does not want to take off, it may have a hindlimb problem. If the horse jumps flat, it may have a back problem. If the horse is reluctant to land, it may have a forelimb problem.

If a horse is presented for evaluation for poor performance, it is important to try to assess the orthopedic component. About 50% of horses with poor performance are lame. When did the horse last race, and over what ground conditions? Did the jockey make any comments when he dismounted? Has the horse coughed? Is rectal temperature routinely monitored? Routine hematological examination and measurement of fibrinogen, comparing results with a baseline for that horse, are useful for detecting systemic abnormalities. Endoscopic examination of the upper airways and trachea, combined with a tracheal wash, are useful screening tools to eliminate a respiratory component to the problem.

The clinical examination does not differ from a routine lameness evaluation of any other type of horse, but because many horses have chronic problems with which they have been living until more obvious lameness supervened, the entire horse should be assessed, not just the postulated lame limb. In view of the high incidence of SDF tendonitis and suspensory desmitis, particular attention should be paid to the palmar metacarpal soft tissues. If the horse has a history of a fall while jumping, particular attention should be paid to the neck, back, and pelvic regions.

A thorough clinical examination may reveal palpable abnormalities in the palmar metacarpal region, evidence of effusion, or pain on flexion of a particular joint. Skeletal pelvic asymmetry or muscle wastage over the quarters also may be evident. Back and pelvic reflexes and the tone of the back and pelvic muscles should be assessed. Is any evidence of guarding apparent? Abnormal shoe wear may give clues about which limb or limbs are lame, which is otherwise not always easy to determine in a horse moving short because of pain in several limbs.

Dynamic examination at the walk and trot in a straight line, followed by flexion tests, should be followed by examination on firm and soft going on the lunge at the trot and canter. The horse should be turned tightly to the left and to the right. If a history of a fall exists, a complete neurological examination should be performed.

If a horse is lame after a recent fall, the investigative approach depends on the degree of lameness and the rate of improvement. A horse with a pelvic injury is usually very lame initially, although lameness associated with an ilial wing fracture usually improves substantially within 24 hours. Lameness associated with an ilial shaft fracture is usually persistent, and the horse remains extremely lame. These horses should be crosstied, assuming the horse’s temperament is suitable. Some ilial wing fractures can be detected with ultrasonography, but the diagnosis of others requires nuclear scintigraphy. Nuclear scintigraphy may give false-negative results if done before 5 to 7 days after injury. If a horse shows only mild to moderate lameness after a recent fall, the horse generally is allowed rest for 7 to 10 days and is then reassessed, and only if lameness persists is further investigation carried out.

Diagnostic Analgesia

If no obvious cause of lameness is apparent, then diagnostic analgesia is performed, but no particular differences in approach exist for this type of horse. However, if clinical signs suggest an intraarticular problem, such as synovial effusion and pain on passive manipulation of a joint, then intraarticular analgesia of the suspect joint may be performed first. If intraarticular analgesia is carried out, clipping a small area is preferred, but some trainers are reluctant to allow this, and provided that the hair coat is not excessively long, a timed 5-minute surgical scrub is performed before injection.

If a fracture is suspected based on the history or clinical signs, diagnostic analgesia is not performed. A horse that pulled up lame on the gallops or finished work and then became severely lame while walking home may have a stress fracture. Stress fractures of the third metacarpal bone (McIII), the third metatarsal bone (MtIII), and the tibia are common. If a stress fracture is suspected, the horse is examined radiographically or scintigraphically.

If soft tissue swelling is identified clinically, then ultrasonography is performed routinely as the next diagnostic step.

Imaging Considerations

Radiography is performed routinely using standard radiographic images. Special images at different angles may be required for demonstrating specific lesions, based on the preliminary examination. Some stress fractures are difficult to identify radiologically, and if a fracture is suspected on clinical grounds, radiographic examination is repeated 10 to 14 days later.

If the clinician suspects an abnormality of the palmar metacarpal soft tissues, an ultrasonographic examination should be performed. In view of the high incidence of bilateral lesions, both limbs should be examined routinely. A systematic approach is essential, focusing on the SDFT, deep digital flexor tendon, and suspensory ligament (SL) in turn. It is almost invariably necessary to clip the metacarpal and metatarsal regions to achieve satisfactory image quality, because most National Hunt horses have thick guard hairs. However, satisfactory images of the pelvis usually can be obtained after washing with chlorhexidine for about 10 minutes, soaking with alcohol, washing off (to avoid alcohol-induced damage to the transducer), and liberally applying coupling gel.

Transverse and longitudinal images of the metacarpal and metatarsal regions are required to gain a full appreciation of the severity of injury. An injury index giving a quantitative assessment of damage can help in communication with trainers and may help to convince them of the clinical significance of an injury associated with only mild clinical signs. Each structure should be evaluated sequentially from proximally to distally at predetermined measured intervals (4 or 5 cm) distal to the accessory carpal bone or each zone should be examined (see Chapter 16). Cross-sectional area (CSA) or circumferential measurements are made at comparable sites in each limb. Measurement of the size of damaged fibers is also useful. One author (RvP) describes the severity of a core lesion by multiplying the percentage of CSA of the tendon damaged by the length of the lesion and by the percentage of the fibers damaged within the injury (assessed visually). For example, a core lesion that occupies 10% of the CSA of the tendon, extends 10 cm proximodistally, and is assessed visually as having 75% of the fibers within the core lesion damaged has an index of 10 × 10 × 0.75 = 75. A similar lesion occupying 30% of the CSA has an injury index of 30 × 10 × 0.75 = 225. All images should be recorded routinely for future comparisons.

Nuclear scintigraphy is indicated as a screening tool when a lame horse is presented after a bad fall, particularly when a moderate-to-severe lameness has persisted for more than 3 or 4 days. Scintigraphy also may be indicated if severe, sudden-onset lameness occurs with no localizing clinical signs to rule out fracture before a dynamic workup is contemplated. Scintigraphy often is more rewarding in horses with acute injuries than those with chronic lameness. Scintigraphy usually can be targeted to specific areas such as the pelvis or both hindlimbs unless the horse has lameness involving several limbs. During evaluation of the pelvis, radioactive urine in the bladder can confound interpretation. The use of furosemide may help, but this drug may make the horse fidgety, and catheterization of the bladder, followed by flushing with warm water, may be preferable.

Proceeding without A Diagnosis

National Hunt horses have a longer career than flat racehorses, and less prize money is available to be won. Therefore the pressure to get a horse sound quickly often is less, and many trainers accept resting the horse if a diagnosis cannot be achieved by the techniques described previously. However, an attempt to reach a diagnosis always should be made.

Shoeing Considerations and Lameness

Most National Hunt horses train and run in light steel shoes with one toe clip in front and two side clips on hind shoes. Some trainers change to a hind shoe with a single toe clip for racing. Good shoeing is essential. Given the high incidence of foot problems causing lameness, a good relationship with a skilled farrier is invaluable. Poor foot conformation, especially low collapsed heels, may predispose the horse to SDF tendonitis. Bar shoes combined with a rolled toe often are used for horses with collapsed heels. If a foot is conformed poorly, the risk exists of shoes being pulled off repeatedly in training, particularly if the branches of the shoe are set too far medially or laterally.

Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in Steeplechasers, Hurdlers, and Point to Point Horses

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a 16% to 43% incidence of SDFT injuries in National Hunt horses, with some reports but not all studies documenting variations among trainers (10% to 40%).7,10,11 Although most of the injuries occur in the forelimbs, hindlimb injuries also occur. Horses 5 years old or younger were less at risk, whereas the maximum injury rate was seen in horses 12 to 14 years of age.9 Many trainers routinely assess forelimb SDFTs daily, and some are adept at detecting relatively subtle lesions. Veterinary involvement may enhance these skills. Many, but not all, trainers are keen to have ultrasonographic assessment of suspected tendon injuries. Some trainers tend to ignore suspicious injuries at the end of a season, contrary to veterinary advice. This may be one reason why a peak incidence of tendon injury tends to occur at the beginning of the season when horses start galloping after a short summer break. Other horses may have been kept in training late in the season to get an extra race and may have sustained injury, which may or may not have been manifested clinically. A second peak incidence of injuries tends to occur at the end of the season, perhaps related to races run on faster going. SDF tendonitis is more common in steeplechasers than in hurdlers, but this may reflect the older population of the horses rather than the type of racing itself. The degree of lameness at the time of acute injury may reflect the severity of tendon damage.

Horses with acute lesions are managed with aggressive antiinflammatory treatment for 5 days, including systemic nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (e.g., phenylbutazone and eltenac), with or without a single dose of corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone), and cold hosing several times daily. Cold water bandages or cold kaolin is applied to the limbs. Some thin-skinned horses are prone to blistering, so any bandaging must be done with care. Other popular proprietary poultices, such as Animalintex (Robinson Animal Health Care, Chesterfield, United Kingdom) and a variety of clay-based preparations, may irritate small unnoticed wounds and are therefore avoided.

An initial ultrasonographic examination is performed about 7 days after the injury is first recognized. Horses with central core lesions may be treated by decompression, using needle fenestration or a fixed blade. This is performed with the horse sedated and with use of regional analgesia. Follow-up ultrasonographic examinations frequently are performed 3 to 4 weeks after injury, because the preliminary examination may underestimate the degree of damage because of ongoing enzymatic degradation. This gives a baseline scan for the injury.

Many differing views are given on the best management of SDF tendonitis in National Hunt horses. Adequately rehabilitating a tendon that was injured late in a season so that the horse can race the following season without a disproportionately high risk of reinjury is difficult. Firing remains a popular treatment, and because many owners and trainers are prepared to rest a horse for 12 months after firing when they would not give such a long convalescent period if rest alone was recommended, this treatment still is carried out widely. Nonetheless, the reinjury rate remains high, so many alternatives have been tried with various success. These alternatives range from at least 9 months of field rest, intralesional injection of hyaluronan, polysulfated glycosaminoglycan, a phenol derivative, β-aminopropionitrile fumarate, platelet-rich plasma, or growth factors, combined with a variety of exercise regimens. Intralesional β-aminopropionitrile fumarate combined with a strictly controlled exercise program has produced good results in selected horses (RvP, SJD) but is no longer commercially available; however, the time for return to racing often is prolonged, in part dictated by the time of injury and the seasonal nature of racing. The average time to return to racing was 17 months. Preliminary results with cultured mesenchymal stem cell injections indicate that recurrent injury rate after treatment may be reduced compared with other treatments.12 The reinjury rate in the injured or contralateral limb 2 years after returning to full work was approximately 33% in 83 horses treated with mesenchymal stem cells12 compared with 55% of 28 horses managed conservatively or with β-aminopropionitrile fumarate.13 Forty-two percent of horses treated with mesenchymal stem cells were still racing 2 years after returning to full work.12 The owner or trainer must be committed to at least 3 to 4 months of walking exercise after treatment, and some horses are unsuited to this temperamentally, unless a horse walker is available. Regardless of the methods of management, a slow, gradual rehabilitation before resumption of ridden work seems beneficial. Ideally the horse should be walking on a horse walker daily for 3 months before resuming ridden exercise. The horse can be turned out during this 3-month period. A cage horse walker in which the horse is free and in which the speed can be set manually to encourage the horse to walk briskly is best.

Serial ultrasonographic examinations are particularly useful as exercise is resumed—about 1 month after walking begins, then again before cantering commences, and a third time before fast work commences. Commonly as work intensity increases, small hypoechogenic areas develop, especially in areas in which the fiber pattern is not parallel. In some horses these lesions disappear, provided the horse is maintained at the same exercise level, whereas in others a core lesion redevelops, and the trainer should be warned accordingly.

The prognosis is related partly to the severity of injury.14 In a follow-up study of 73 National Hunt and point to point racehorses, lesions were graded by ultrasonography as mild (<50% CSA or <100 mm in length), moderate (50% to 75% CSA or 110 to 160 mm in length), or severe (>75% CSA or >160 mm in length). All mildly affected horses returned to training, and 63% raced. Fifty percent of horses with a moderate lesion resumed training, and 23% raced. However, only 30% of horses with severe lesions resumed training, despite up to 6 months longer convalescence, and 23% raced. The mean reinjury rate of those resuming work was 40% in the period of follow-up (9 to 30 months).

The type of racing in which the horse is involved may influence the prognosis for return to racing after SDF tendonitis. Fifty-one (73%) of 70 hurdlers raced five or more times after desmotomy of the accessory ligament of the SDFT for treatment of tendonitis compared with 39 (58%) of 67 steeplechasers.15

Cellulitis, skin necrosis, and necrosis of the underlying SDFT are poorly understood conditions that have been recognized in National Hunt horses (SJD) and flat race horses that have run over long distances (> miles) (RvP). Many horses run in boots or exercise bandages, which are removed after racing. Whether exercise bandages would be on long enough to cause pressure necrosis is debatable. The typical history is that a proprietary claylike substance (Kaolin, Ice-Tite) or commercial poultice (e.g., Animalintex) is applied to the metacarpal regions after racing, with or without overlying bandages. The applied substance is removed the following day. Clinical signs may be apparent within 24 to 72 hours, with the development of peritendonous edema and serum ooze, progressing to skin slough and slough of deeper tissues, which may take several weeks. The degree of damage varies among horses, and one or both limbs may be affected. One author (SJD) has seen this unassociated with SDF tendonitis, whereas another (RvP) often has seen concurrent SDF tendonitis. The prognosis depends on the depth of the lesions. One author (RvP) recommends that horses be thoroughly cooled after racing before anything is applied topically to the limbs, to minimize the risks of these complications. If a SDFT injury is suspected, then the advice of the course veterinarian should be sought.

miles) (RvP). Many horses run in boots or exercise bandages, which are removed after racing. Whether exercise bandages would be on long enough to cause pressure necrosis is debatable. The typical history is that a proprietary claylike substance (Kaolin, Ice-Tite) or commercial poultice (e.g., Animalintex) is applied to the metacarpal regions after racing, with or without overlying bandages. The applied substance is removed the following day. Clinical signs may be apparent within 24 to 72 hours, with the development of peritendonous edema and serum ooze, progressing to skin slough and slough of deeper tissues, which may take several weeks. The degree of damage varies among horses, and one or both limbs may be affected. One author (SJD) has seen this unassociated with SDF tendonitis, whereas another (RvP) often has seen concurrent SDF tendonitis. The prognosis depends on the depth of the lesions. One author (RvP) recommends that horses be thoroughly cooled after racing before anything is applied topically to the limbs, to minimize the risks of these complications. If a SDFT injury is suspected, then the advice of the course veterinarian should be sought.

Suspensory Desmitis

Suspensory desmitis is a major problem in National Hunt horses, especially steeplechasers and point to point racehorses.3,10,11 However, in a study of 1119 horses in training followed over two seasons, SDFT lesions were more common (1.71/100 horse months in training) than SL injuries (0.23/100 horse months).11 Injuries of the body or branches occur in forelimbs and hindlimbs, sometimes with a fracture of the distal third of the second metacarpal bone (McII) or second metatarsal bone (MtII), fourth metacarpal bone (McIV) or fourth metatarsal bone (MtIV), apical or abaxial proximal sesamoid fractures, or sesamoiditis. Proximal suspensory desmitis does occur in forelimbs and hindlimbs and is recognized more commonly in hindlimbs, but the true incidence may be underestimated.

Body and branch injuries of the SL often go unrecognized until the ligament is grossly enlarged; possibly some of these are cumulative injuries rather than single-event injuries. More careful monitoring of the SLs by regular palpation with the limb not bearing weight may lead to earlier detection of important lesions. The degree of swelling sometimes makes it difficult to palpate accurately the distal end of the McII and the McIV.

Assessment of structural damage is done by ultrasonography in a way similar to that described for SDFT lesions. Lesions are assessed acutely (up to 7 days after injury and 4 to 6 weeks later) to determine the baseline degree of injury. Some of the swelling contributing to the apparent swelling of a SL branch is often a periligamentous reaction. Radiographic examination is necessary to evaluate the McII or the MtII, the McIV or the MtIV, and the PSBs.

Body and branch injuries are associated with a prolonged convalescence irrespective of the way in which they are managed, and returning to racing often takes longer than for a horse with SDF tendonitis. The rate of recurrent injury is high. Surgical removal of fractures of the McII or the McIV (or the MtII or the MtIV) has little bearing on the horse’s final outcome.

Conservative management of rest alone, splitting the SL, intralesional injections of β-aminopropionitrile fumarate, and pin firing have been used with no clinically significant differences in outcome. There is anecdotal evidence that mesenchymal stem cell treatment or platelet-rich plasma may improve healing and reduce reinjury rate.

Lameness Associated with the Carpus

Synovitis and OA of the middle carpal joint are common and are treated by intraarticular injection with hyaluronan, with or without triamcinolone acetonide. A horse with synovitis may be treated more conservatively than a flat racehorse when the pressure is great to maintain the horse in training if at all possible. With a young National Hunt horse with a career of several years ahead, restricting the horse to walking exercise until clinical signs have resolved fully often is more prudent.

Chip fractures of the dorsal border of any of the carpal bones are common and often are associated with preexisting OA. Treatment is by surgical removal of the fragment(s), and prognosis depends on the degree of OA; most horses are able to return successfully to racing. Slab fractures of the third carpal bone are also common but are not always associated with obvious clinical signs. Lameness is often mild and associated with only slight effusion of the middle carpal joint.

Accessory carpal bone fractures usually result from a fall and are common in National Hunt horses. Most fractures are longitudinal (vertical) and occur midway between the dorsal and palmar borders of the bone, but less commonly articular chip fractures occur on the proximal or distal dorsal articular margin. The latter must be removed surgically; otherwise, severe OA ensues. Horses with the more common longitudinal fractures do not require treatment other than prolonged rest. Some fractures heal only by fibrous union, but the prognosis for return to racing is good. Some horses have effusion in the carpal sheath when work is resumed, which responds well to the intrathecal administration of triamcinolone acetonide and for which retinacular release is seldom necessary.

Lameness Associated with the Hock

The degree of lameness caused by hock pain varies, and lameness is more commonly unilateral, unlike the bilateral lameness usually seen in the flat racehorse. The most common cause is osteoarthritis (OA) of the distal hock joints, although traumatic injuries also occur. The horse may adduct the lower limb as the leg is brought forward at the walk and trot. The lameness often worsens after flexion and when the lame limb is on the inside on the lunge. More subtle signs of poor jumping or back pain may herald a problem originating in the hocks.

Lameness most often is alleviated by intraarticular analgesia of the tarsometatarsal joint. It is rare to have to inject the centrodistal joint as well, despite the variable communication between the joints and the fact that osteoarthritic changes seen radiologically often affect both joints. Radiography of the hocks should include four standard views, because radiological changes may be visible only on one projection. Abnormalities range from mild periarticular osteophyte formation to osteolysis, with narrowing of the joint spaces, with or without periarticular new bone. Occasionally, young horses in the first year in training have clinically significant radiological changes in one limb. The damage was probably present before onset of training and may be associated with collapse of the distal tarsal bones or a traumatic incident earlier in the horse’s life.

Care should be taken when interpreting scintigraphic images of the hocks in National Hunt horses. Often areas of increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU) are seen but do not appear to correlate with clinical signs of lameness. Treatment of horses with OA of the distal tarsal joints usually consists of intraarticular medication of the tarsometatarsal joint with combinations of hyaluronan and corticosteroids. Consideration should be given to chemical fusion of painful distal hock joints in young National Hunt horses.

Traumatic injuries involving the hock are common. Injuries frequently sustained after a fall include fracture of the lateral malleolus of the distal aspect of the tibia and tearing of the attachments of the collateral ligaments. The lameness in horses with lateral malleolar fractures can be mild, and lesions may be missed if radiography is not carried out. Ultrasonography may be more useful than radiology for the early diagnosis of collateral ligament injury. Follow-up radiology some weeks later may reveal some entheseous new bone formation. Horses with these injuries have a good prognosis for a return to racing, although improvement in lameness may be slow. Some debate exists about the optimal management of horses with lateral malleolar fractures: conservative or surgical. Both treatments carry favorable prognoses. Surgical removal is usually easiest by making an incision directly over the fracture fragment(s) rather than by attempting arthroscopic removal. Arthroscopic surgical techniques can be used successfully, particularly if motorized equipment such as a synovial resector is available to improve visibility and help with dissection of ligamentous attachments (Editors).

Lameness Associated with the Pelvis

Lameness associated with the pelvis in the National Hunt horse is more likely to result from a traumatic incident than a stress fracture. Falls or poor landings while jumping (see Figure 112-4) may lead to subluxation of the sacroiliac joint or pelvic fractures. However, ilial stress fractures also occur, especially in horses entering training at 5 years of age or older. A strong correlation between pelvic lameness and working horses on loose all-weather surfaces, especially on unmanaged wood chip surfaces and particularly uphill, has been noted (AS, RvP). In a study of 1119 horses in training followed over two seasons there were 111 fractures, 17% of which were pelvic fractures.11

Clinical signs can vary from severe lameness with obvious crepitus to mild stiffness. It is important to examine the pelvis per rectum when pelvic damage is suspected. A horse with an ilial fracture sustained during a fall may be lame initially and improve rapidly within 48 hours. If an ilial wing fracture is nondisplaced, the horse could return to cantering exercise before lameness recurs. Muscle spasm may result in substantial asymmetry of the tubera coxae in the acute stage, but this usually also resolves within 24 hours. Severe lameness associated with an ilial shaft or acetabular fracture is invariably persistent. Ilial stress fractures may cause only mild clinical signs, and sometimes the most important abnormality is shortening of the contralateral forelimb stride as the horse moves off from standing still. This gait abnormality rapidly resolves.

Fractures of the ilial wing involving the dorsal surface often can be diagnosed by ultrasonography, but incomplete stress fractures involving the ventral aspect cannot be seen.

Nuclear scintigraphy is invaluable for assessing pelvic pain. Assessment of pelvic fractures should be delayed for at least 5 to 7 days after injury to avoid false-negative results. If scintigraphy indicates IRU in the region of the coxofemoral joint, obtaining numerous oblique scintigraphic images is worthwhile to try to assess whether the fracture involves the joint. Other scintigraphic changes seen include IRU at the greater and third trochanters of the femur associated with damage to the insertions of the deep and middle gluteal tendons and the superficial gluteal insertion, respectively.

Horses with nondisplaced ilial wing fractures have a good prognosis, whereas the prognosis for those with fractures of the ilial shaft16 or ilial fractures involving the acetabulum is poor.

Lameness Associated with the Front Feet

Lameness associated with the front feet may vary from a shortened gait to obvious lameness. The most common causes of foot lameness include solar bruising, corns, and subsolar abscesses. Other commonly recognized causes of foot lameness in the National Hunt horse include pedal osteitis, palmar foot pain, and fractures of the distal phalanx. Palmar foot pain may be caused by bruising of the heel bulbs or may be caused by deeper pain associated with the deep digital flexor tendon or navicular bone, with a much poorer prognosis. Horses that train on downland are particularly at risk for bruising of the feet or penetrating injuries of the sole caused by flints. The latter may result in infectious osteitis of the distal phalanx. Protective aluminum pads may prevent solar penetrations but do not prevent bruising, because the pad is distorted and puts pressure on the sole if a horse stands on a flint.

In horses with chronic lameness associated with foot pain, local analgesia, radiography, and ultrasonography sometimes can be unrewarding or give equivocal results. Nuclear scintigraphy using soft tissue and bone phase images is sometimes helpful. Magnetic resonance imaging is increasingly useful.

Fractures of the Third Metacarpal and Metatarsal Bones

The most common long bone fractures in National Hunt horses are condylar fractures of the McIII (or the MtIII) and pelvic and tibial fractures. In a study of 1119 horses followed in training over two seasons, there was a total of 111 fractures, 17% of which involved the McIII or the MtIII.11 Former store horses were more at risk of fracture than former flat racehorses, although this difference was not significant. Fractures of the MtIII frequently involve the medial condyle and may spiral proximally. Full evaluation of the fracture may require numerous oblique radiographic images of the MtIII. Such fractures are more common in hurdlers than in steeplechasers. With prompt surgical treatment by internal fixation, the prognosis is good. Compound, comminuted fractures of the distal aspect of the McIII and the MtIII may occur during racing and may be associated with luxation of the fetlock. These horses have a guarded prognosis for return to racing.

Incomplete proximal palmar cortical fatigue fractures of the McIII occur commonly, especially in horses older than 4 years of age entering National Hunt or point to point training for the first time. Preexisting increased radiopacity in the proximomedial aspect of the McIII detected when lameness is first recognized in some horses suggests that abnormal bone modeling has existed for some time, subclinically or without clinical signs being recognized. Lesions are often bilateral. Lameness is characterized by the horse becoming lamer the farther it trots and then improving if walked a few steps. Usually no localizing clinical signs are apparent, and diagnosis depends on localizing pain to the proximal palmar metacarpal region and identifying radiological lesions or scintigraphic evidence of increased bone turnover, in the absence of ultrasonographic abnormalities of the proximal aspect of the SL. Treatment of 3 months of rest with a graduated return to work is usually successful, and recurrent injury is unusual.

Less commonly, transverse stress fractures of the distal metaphyseal region of the McIII cause acute-onset lameness. No localizing signs may be apparent, but lameness is alleviated by a four-point nerve block of the palmar and palmar metacarpal nerves. Usually preexisting callus formation is evident on the distal metaphyseal region of the McIII on the dorsal or palmar aspects.

Lameness Associated with the Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Most lameness associated with the metacarpophalangeal (fetlock) joint is degenerative. Fetlock lameness is often present bilaterally with a shortened forelimb gait, warmth around the joint, and reduction of range of motion. Flexion often exacerbates lameness. Lameness often is improved by intraarticular analgesia of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Radiography may reveal periarticular osteophytes or a small fragment on the dorsoproximal border of the proximal phalanx. If the PSBs and SL attachments are involved in sesamoiditis, a low palmar or four-point nerve block is required to alleviate lameness. New bone formation and osteolysis may occur on the abaxial surface of the PSBs at the attachments of the SL. This form of sesamoiditis more commonly is associated with damage to the attachments of the SL onto the PSB rather than a primary PSB disease and is seen much more frequently in National Hunt horses than other types of horses. The condition is related to the stress to which the palmar metacarpal soft tissues are subjected during jumping and galloping.

Treatment options include the following:

The prognosis for lameness affecting the fetlock is more guarded in the National Hunt horse than in the flat racing horse but such lameness occurs much less frequently.

Neck Lesions

Neck trauma usually results from a fall (see Figure 112-6) and is more common in steeplechasers and point to point racehorses than in hurdlers.2-7 Neck trauma may result in ataxia or a stiff neck, with or without forelimb lameness, and can cause death. Ataxia may be transient or persistent. Radiographic examination should be performed if ataxia or neck pain and stiffness persist for more than a few days. Fractures in the cranial or midneck regions are most common, but occasionally fractures occur caudally, which may be difficult to assess without a fixed, high-output x-ray machine. Nuclear scintigraphy can be helpful in localizing such fractures, but false-negative results in the caudal cervical spine are possible. Horses with persistent ataxia have a guarded prognosis. Most horses with a fracture unassociated with ataxia can return to racing despite residual neck stiffness.

Back Pain

Back pain in the National Hunt horse may be primary or may develop secondary to chronic lameness in one or more limbs and is being recognized with increasing frequency. Nuisance problems include the development of seromas underneath the saddle, which are probably attributable to an ill-fitting saddle and poor riding. Most trainers regularly use a physiotherapist, who may be the first person asked to look at a horse that is not right. Only if the horse fails to respond to one or two treatments, or if the physiotherapist recognizes obvious lameness, is veterinary advice sought. A good working relationship with the physiotherapist is valuable, because without a doubt the rehabilitation and long-term management of horses with chronic back pain can be helped by regular physiotherapy treatment. Moreover, certain findings on palpation have been shown to predict the occurrence of some pelvic and hindlimb fractures.17 However, the veterinarian should have responsibility for both the diagnosis and the development of the treatment program.

Knowledge of back problems in National Hunt horses has increased greatly with more routine use of nuclear scintigraphy. Thorough investigation of the back is warranted in horses with chronic back pain, with a history of jumping awkwardly (see Figure 112-1), or after bad falls. Physical examination of the back often can be unrewarding concerning specific diagnosis, because the examination may reveal only stiffness and pain on palpation. Underlying problems such as active kissing spines (impinging, overriding, or overlapping dorsal spinous processes) or OA of the synovial intervertebral articulations (facet joints) are common in National Hunt horses and can be ruled in or out using scintigraphy and radiography. In a horse with an acutely sore back after a fall, scintigraphy can be used to determine if any bony damage occurred. The clinician should bear in mind that falls may involve more than one horse, and a fallen horse may get shunted (pushed) by one behind. Serious vertebral fractures can produce nothing more than severe stiffness and guarding in some horses after a fall, if the spinal cord itself is not compromised. For example, scintigraphy may reveal intense focal IRU suggesting a fracture in the region of the second or third lumbar vertebra. Radiology may demonstrate an obvious change in orientation of the spinous processes at this level, without being able to demonstrate a fracture. Lateral and dorsal scintigraphic images are useful to identify fractures of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae.

Ultrasonographic examination is also useful for identifying some soft tissue injuries such as desmitis of the supraspinous or dorsal sacroiliac ligaments.

Horses with traumatic injuries often respond well to prolonged rest combined with physiotherapy. Horses with kissing spines often improve after local infiltration with corticosteroids.

Successful management of chronic back pain needs a broad approach. Many National Hunt horses have an inadequate jumping education and poor technique (see Figure 112-1). Traditionally in the United Kingdom and Ireland, horses learn to jump by loose schooling over small fences; horses are schooled ridden over two or three small fences, once or twice when they are fresh. In France horses often are trained to jump out of deep going, when they are tired, providing a better grounding for racing conditions. The standard of riding of the work riders is often only moderate, and employing some staff with a background of working with event horses or show jumpers may be beneficial. Time should be spent teaching the horse to jump properly. Often more time is available in the summer break period to devote to such problems.

Additional work from the field, or keeping the horse in work, or bringing the horse in early should be advised. The horse should be encouraged to work in a round outline by exercising in draw reins to improve the development of the epaxial muscles. The horse can be given a warm-up period on a horse walker before being ridden. Use of a well-fitting hunting saddle rather than a racing saddle should be encouraged. After exercise the horse may benefit from being led home from the gallops rather than ridden.

Other Injuries

National Hunt horses seem particularly vulnerable to lacerations involving the distal palmar (plantar) aspect of the metacarpal (metatarsal) region, which may involve the SDFT or the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS), usually resulting from the horse being struck or from penetration by a sharp stone. Such horses with these injuries should be treated early and aggressively, especially if the DFTS is involved. With early lavage of the DFTS using an arthroscope, combined with intravenous broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment for 5 to 7 days, the prognosis is usually excellent unless substantial damage of the SDFT has occurred.

A high number of complex injuries to the palmar (plantar) soft tissues of the pastern have been seen in National Hunt horses as sequelae to previous SDF tendonitis in the metacarpal region or as primary injuries. Although injury to one or both branches of the SDFT may occur alone, simultaneous injuries of the oblique and straight sesamoidean ligaments are not uncommon. The prognosis for horses with such injuries is generally guarded.

Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in Timber Racing Horses

Lameness falls into three groups: acute injury or breakdown after racing, chronic wear injury caused by the horse’s age and length of competitive career, and traumatic injuries caused by interference from another horse or hitting a fence.

Eighty-five percent of acute injuries after racing are caused by SDF tendonitis and SL desmitis. Many timber horses have had previous SDFT injuries from earlier flat racing. The long courses (up to 4 miles), variable turf quality and terrain, fatigue, and poor weather conditions predispose horses to injury. Injuries range from small tears to catastrophic breakdowns that may necessitate humane destruction. Regular clinical and ultrasonographic monitoring is useful for detecting subtle changes and for making recommendations about running on specific footing (ground) conditions (KK).

Once recognized, horses with OA of the metacarpophalangeal and the distal hock joints require management, because increased lameness may be induced by the increased work leading up to a race. Keeping horses as comfortable as possible throughout training is preferable, which may necessitate intraarticular medication two or three times during a season, using hyaluronan for the metacarpophalangeal joints and hyaluronan and corticosteroids for the distal hock joints (KK). Orally administered glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are used commonly. It is important to keep the horse well shod and to use cold hydrotherapy after strenuous exercise.

Traumatic injuries sustained during racing are common, with the hindlimbs particularly vulnerable because of the horse hitting fences at speed. Damage to the quadriceps muscles, periarticular soft tissues of the stifle, and stifle joint is common, although determination of the severity of injury is usually easiest several hours after a race rather than immediately. Radiological examination is indicated to rule out a patellar fracture, which requires surgical management. Bruising of the patellar ligaments is common, with or without effusion of the femoropatellar joint, and is treated by drainage of excess synovial fluid and injection of hyaluronan (4 to 6 mL) combined with controlled exercise and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Timber shin describes firm enlargement of the dorsal aspect of the metatarsal region because of chronic bruising of the long digital extensor tendon, with fibrosis of the tendon and peritendonous soft tissues. Timber shin is unsightly and is not associated with long-term lameness, but recent trauma results in lameness from severe swelling of the leg, with pain on protraction.

Injuries sustained by interference from another horse, for example, traumatic heel bulb laceration or strike injuries on the palmar or plantar aspect of the fetlock, are common (see other injuries on this page). Injuries also can result from falls—for example, fracture of the accessory carpal bone—or from a galloping horse treading on a faller.