5 Palpation

One of the main keys to success with massage lies in the sensitivity of the therapist's hands. A well-developed manual sensitivity is important for:

• Examining and assessing tissues;

• Recognising the end-feel of the tissue, which influences the effectiveness and comfort of the massage;

• Modifying techniques to different tissues and tissue layers;

• Adapting techniques to suit an individual's tissues; and

• Adapting techniques so that they are appropriate to various pathological states and stages of healing.

Exercises to develop palpation skills

The student therapist may increase her sensory awareness by practising on inanimate objects as well as on the human body. To begin, it is helpful to find a friend who is willing to model; it is easier to develop palpatory skills when you do not have to concentrate on giving a massage simultaneously. There are many exercises that can help to develop palpatory awareness; a few of them are listed below but you will also benefit by making up some of your own. Make a habit of touching objects that are a part of your daily life. While you are doing so, describe the sensations to yourself; try giving words to what you feel so that you begin to differentiate—lots of things feel ‘like’ something else, but try to find the subtle differences between them. Palpate with the pads of your fingers and thumbs, which are highly innervated:

• Take two small bowls and put refined white flour into one and wholewheat flour into the other. Simultaneously put one hand into each and rub the flour between your fingers. Describe to yourself the different sensations.

• Collect together a number of different grades of sandpaper. Close your eyes and attempt to sort the paper by grade.

• Compare the differences in the texture of water, cooking oil and a thick body lotion by rubbing a little of each between finger and thumb.

• Place some small objects on a table (e.g. grains of rice, a piece of string, a matchstick, a key, a paperclip). Cover them with a thin cloth and palpate; repeat with thicker coverings such as a blanket and a piece of foam. Distinguish the variation of sensations between the covers and note any differences in the pressure you have applied.

• With one finger stroke your cheek, your arm, your palm, your abdomen, your knee and the sole of your foot. Feel any varying texture, skin temperature and moisture in these parts of the body.

• Practise palpation in the area of your wrist and forearm. The anterior aspect of the wrist is a good place to start; here you can see and feel the tendons and blood vessels. Let the fingers of one hand rest as lightly as a feather on your contralateral wrist. Move them very gently over the skin without stretching and register what you feel. Now apply slightly more pressure, so that the skin moves with your fingers; this should give you more information about the structures under the skin. Apply more pressure still so that the subcutaneous structures are compressed on the underlying bone. With this heavy pressure the sensitivity of your palpation decreases and the structures will not be so easy to differentiate.

• Palpate your own thigh. Note the depth of pressure required to gain information about the tone of the muscles in this region. Using your whole hand pick up and stretch the muscles and register any changes you feel in the resistance of the tissues.

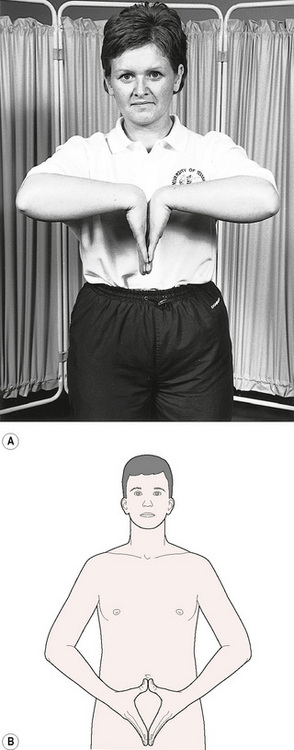

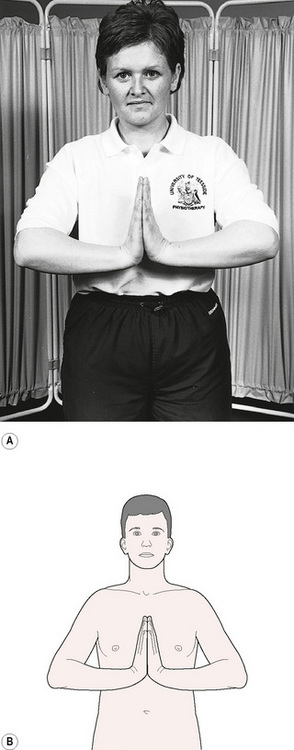

It is useful to perform specific exercises to increase the mobility of your hands before you begin to learn massage. Figures 5.1 and 5.2 show suggested exercises for stretching your fingers and wrists.

Palpation technique

To palpate effectively, the pads—rather than the tips—of the fingers should be used. The fingers should be straight but relaxed, with movement coming from the arm, not the intrinsic muscles of the fingers.

Layer palpation

As your hands progress from layer to layer, you should visualise each one in turn and mentally register differences in the quality of feeling that each layer has.

Epidermis

Rest your hands lightly on the surface of the skin of your patient/model. The first thing you should be aware of is the temperature. If you choose to compare the temperature of different parts of the skin, use the same hand (in case the temperature varies between your right and left hands), and it is best to use the dorsum rather than the palm. Slide the hand slowly over the skin, firmly enough not to tickle. Dryness, scaliness, sweating and smoothness will be immediately detectable. A visual reinforcement of palpation findings can be useful, so look for circulatory alterations in the skin. Any scarring will be palpable, as will any hot inflamed areas. You should note the patient's reaction to touch at this point: observe any alternations in facial expression (unless the patient is prone) and feel changes in underlying muscle tone. If the fingers remain at this depth but move on the skin, rather than over it, a wrinkle of skin will be formed around the fingertips, in front of the movement. This is because the epidermis is being pushed against the points of underlying adherence. A shear force is being created between the layers. As you push the epidermis, you almost immediately reach a point of resistance at which you will start to glide over the skin surface if your pushing continues. This is the end-feel, i.e., the feeling at the end of the movement (see below).

Dermis and subcutaneous layers

Next, ease a little further into the tissues by allowing the fingers to sink down a little. If done lightly, the fingers will come to rest in the subcutaneous layer. You should then ease off a little to feel the dermis.

Fascial layer

To reach the fascia, you should find a place where muscle attaches to bone subcutaneously, or where a fascial intermuscular septum lies immediately under the skin. Elsewhere, from a position where the fingers have come to rest on the subcutis, push down slightly deeper to feel the final layer of tissue surrounding the muscles, but take care not to compress the tissues between your fingers and underlying bone.

Muscle

Knowledge of anatomy will inform you when you are sinking into muscle. This is firmer than subcutaneous tissue, and so offers more resistance to your fingers. It has specific tone. The fibre bundles may also be apparent, as the muscle will feel ‘ridged’. In erector spinae, it may be possible to feel a thick rounded cord which can often extend several inches. This is a group of muscle fibres which have increased in tone over a period of time, common in such a postural muscle. If it has been present for any length of time, surrounding connective tissue will be tight or may be partly fibrotic, in which case it will feel hard and will be less readily responsive to massage. Slide your fingers right over the muscle and feel its edge and then its fascial attachment.

Other structures

• Tendon feels like a thin firm cord which can often be moved or ‘twanged’. This is easy to achieve on the tendons of the wrist which can be seen and palpated on the flexor aspect.

• Ligament is usually felt as a discrete flattened band of dense connective tissue. Careful palpation on the medial side of the knee will identify the edges of a band of slightly denser tissue, which is the medial collateral ligament. On the lateral aspect of the knee it is possible to palpate a cord-like rounded structure stretching from the head of the fibula to the femoral condyle. This lateral collateral ligament is much rounder than the ligament on the medial side, but is denser than a tendon. Compare it with a tendon, which has a more mobile, elastic quality to it.

• Joint capsules or synovium can usually be palpated only if they are thickened. A capsule feels like a thickening over the line of the joint whereas a synovium has a more ‘silky’ feel.

• Peripheral nerves feel like small threads—much thinner than tendon, less elastic and difficult to feel because of their thinness. They are often fairly mobile and, if flicked, movement may be seen a few centimetres further along the course of the nerve.

End-feel

Recognition of the end-feel is essential for accurate localisation of the technique and for pain-free massage. As defined earlier, it is the feeling at the end of the available movement and it can be identified at each tissue layer and in joints. Initially, movement in the tissues is effortless. As the tissues near their limit of movement, a little extra effort is required to move them. The resistance increases until movement stops. Pushing through this end-feel will create traction between this layer and the next, and will cause you to lose your layer localisation. Continuing to push further will then cause discomfort to the patient. The quality of the end-feel varies with different tissues and will give information as to what has stopped the movement—whether it is the microstructure of the tissue itself, and therefore feels normal for that particular tissue, or whether it is altered because of an abnormality. In the epidermis, the fingers slide over the skin before any resistance is felt. In the dermis and subcutis, the end-feel is pliant. It is firm in fascia and elastic in muscle. Working within the end-feel will maintain but not increase mobility. Working at the end-feel will produce stretch in the tissues, which is necessary for mobilisation. Stretching beyond the end-feel will be uncomfortable and may cause damage. If pain occurs before the end-feel, the tissues are hypersensitive and tender, and this should be respected, as normal movement or squeezing will be perceived as painful. In the absence of trauma or underlying pathology, the skin can be desensitised by gentle massage.

Abnormalities

When palpating within a specific layer or structure, the therapist will encounter abnormalities which may be easy to find, but difficult to recognise. Very gentle palpation can detect a soft ‘sponginess’ which indicates excess tissue fluid in the superficial layers. Acute swelling in these layers is extremely soft and it is easily missed when it lies superficially. Very gentle palpation is required. A chronic swelling is more dense and resistant, but still soft in feel. A very superficial sogginess can sometimes be detected, which creates a peau d'orange effect, where the skin looks like orange peel when squeezed. Tiny indentations made by something as small as a matchstick will leave tiny pits. Gunn (1989) refers to this reflex effect as trophoedema. A long-standing pitting oedema will compress to leave a ‘pit’, the size of the palpating fingertip or thumb, which remains after the pressure is removed. A rapidly occurring very ‘boggy’ swelling around a joint may indicate haemarthrosis, which requires further investigation.

When fluid is discovered in the tissues, the therapist should decide:

• Whether it is lymphoedematous or hydrostatic (from its history and quality) (see Chapter 3);

Occasionally a small area in the tissues will be felt to ‘pop’ and disappear. This is thought to be a patch of enclosed fluid which dissipates under pressure. It can happen under the plantar fascia and should not be confused with crystal formation.

Crepitus can be felt or heard in the soft tissues if chronic fibrosis is present. This is a friction effect due to loss of lubrication and fibrosis in an area of tissue.

Cellulite is seen as an uneven surface and felt as tiny dimples and sectioned tissue. It may be moist, in which case it is enlarged (often perceived by the patient as increased fat) with swelling in the subcutaneous layer. If chronic, collagenous separation of groups of fat cells can be shortened and the tissue will feel hardened.

Any fibrous structure (e.g. aponeurosis) can be thickened as a result of continued tension on an adherent structure. A common example is the insertion of levator scapulae at the superior angle of the scapula. Knowledge of anatomy will indicate that what is felt is a thickened structure.

Myofascial trigger spots (Travell & Simons 1992) can be felt as a hardening in the muscle and diagnosed by the ‘twitch’ test. The spot is exquisitely tender and, when a finger is slid over the muscle fibre, it is seen to twitch.

Abnormality of the tissue interfaces can be felt as a loss of mobility. The normal glide between the interfaces is restricted and produces a sensation of being stuck together; rolling the tissues is impaired. In chronic situations the end-feel can be reached before movement has occurred.

Nodules are sometimes palpated in muscles. They can be herniations of fat through the fascia (Grieve 1990) or ischaemic fibrotic muscular lesions. They may be mobile or adherent, and are often painful on pressure. Their tenderness reduces when circulation and mobility are increased following massage.

With practice, you will become familiar with the feel and behaviour of normal tissues. This will enable you to get the most out of your experience of palpating and treating abnormal tissues, ensuring that your palpation and assessment skills become refined enough for effective practice.

Key points

• Palpation should be undertaken using the pads, not the tips, of the fingers.

• Exercises will help you to develop manual sensitivity.

• Different anatomical structures have their own unique feel.

• Working within the end-feel of a tissue maintains mobility; working at the end-feel will stretch the tissues; and stretching beyond the end-feel will cause discomfort and possible damage.

• Abnormalities in the tissues can be recognised by their own distinctive feel.

Grieve G.P. Episacroiliac lipoma. Physiotherapy. 1990;76(6):308-310.

Gunn C.C. Treating myofascial pain: intramuscular stimulation for myofascial pain syndromes of neuropathic origin. Seattle: University of Washington, 1989.

Travell J.G., Simons D.G. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. vol. 2. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1992.