9 Reflex therapies

This chapter introduces a variety of specialised techniques which are either employed for particular clinical situations or rather complex to use. While the techniques in themselves may not be difficult to learn, their safe application requires sophisticated clinical reasoning and the detailed conceptual framework for this is outside the scope of this book. It is important to emphasise that they are simply introduced here (some very briefly) and must be learned from an experienced practitioner.

Technique: connective tissue manipulation/bindegewebsmassage

Features

Connective tissue manipulation (CTM) is a soft tissue manipulative therapy which is, conceptually, a reflex therapy. It influences cutaneovisceral autonomic reflexes (see Chapter 3) to induce balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. It utilises connective tissue (CT) zones derived from the skin zones of Head and the muscle zones of McKenzie. These are found principally on the back where they can be seen and palpated. The zones are both visible and palpable, with a degree of inter-rater reliability (Holey & Watson 1995) Acute zones are seen as ‘puffy’ raised areas which feel soft to the touch, with underlying tension felt when superficial layers are moved on deeper layers. Chronic zones are recognised as drawn-in areas in which the tissues are palpated as tight and adherent (Haase 1962). They are often hypersensitive. The zones (see Fig. 3.7) are assessed to detect the level of autonomic balance and specific functional problems. For example, a positive liver zone may indicate recent drug therapy, heavy social drinking or disease. The number of visible and palpable zones indicates the generality of autonomic imbalance. The zones can indicate the degree to which imbalance has occurred or can inform progression of treatment or location of strokes to be applied, or can indicate cautions. A specific stretch manipulation is applied to the fascial layer and is thought to stimulate segmental and suprasegmental cutaneovisceral reflexes. All structures sharing the same spinal segmental innervation are stimulated via the autonomic nervous system (ANS), resulting in effects that include vasodilatation and alterations in smooth muscle tone. The suprasegmental effects are mediated in the medulla and wider physiological effects are achieved, such as improved balance between the two components of the ANS, endocrine and hormonal balancing and raised beta-endorphin levels. It produces a feeling of well being and increased flexibility.

CTM must be applied skilfully at the correct tissue interface and must begin at the sacrum to avoid adverse autonomic reactions. The progression of the strokes depends on the aims of treatment and on clinical reasoning. The technique and its clinical application must be learned from an experienced practitioner.

Patients who may benefit from this treatment are those with:

• Local mechanical musculoskeletal problems, for example scarring or shin splints;

• Hormonal problems, for example women experiencing menopausal or menstrual symptoms;

• Visceral problems, for example bowel disorders; and

• Autonomic problems, for example complex regional pain syndrome, intractable nerve root pain.

Application of the different techniques depends on individual patient needs. Generally, the therapist is aiming to use the fascial technique. If this is used inappropriately, adverse reactions such as fainting can occur. The ‘basic section’ must be treated first to induce a parasympathetic response, to prepare the body for stimulation of sympathetic dermatomes. Superficial layers must be prepared first. The preparatory strokes are usually used initially and these are often clinically effective in their own right. Treatment is progressed by working superficial to deep and caudad to cephalad. Care must be taken not to overtreat, due to the possibility of producing adverse reactions. Treatment should always be comfortable, and never painful.

Categories—Preparatory Strokes: Fascial Technique; Skin Technique; Subcutaneous Technique; Flat Technique

Manipulation: fascial (fazien) technique

Purpose

To reduce trophoedematous changes in zonal areas.

To promote fluid level balance.

To achieve balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

To reduce sympathetically maintained pain.

To produce a feeling of well being.

To increase local and general flexibility.

Procedure

This is CTM ‘proper’, which produces the strong autonomic reflex reactions.

The pad of the therapist's third finger makes contact with the skin (Fig. 9.1A).

The finger is reinforced by the ring finger.

The distal interphalangeal joint is flexed, to gather up the slack superficially in the tissues.

The therapist should then push into the end-feel using the hand and arm to exert a traction effect at the fascial layer.

Each stroke must be performed in the palmar or radial direction of the operating hand.

The stroke must be accurately aimed at the correct tissue interface.

The tissues must be adequately prepared by preparatory techniques to produce the desired effect.

Each stroke must produce a cutting sensation and a triple response, or adverse reactions will occur.

All strokes must be within the patient's tolerance of discomfort.

The strokes must begin at the sacrum.

Progression of the strokes depends on the individual patient's response and on the aims of treatment: they can be dictated by the zones, segmental relationships and understanding of the underlying pathological processes.

Manipulation: skin (haut) technique

Procedure

The therapist places all four fingertips on the skin where treatment is required (Figs. 9.1C, D).

The fingertips are lightly and rapidly brushed over the surface of the skin.

The fascial technique is then retried, and should now produce the cutting sensation.

Manipulation: flat (flashige) technique

Procedure

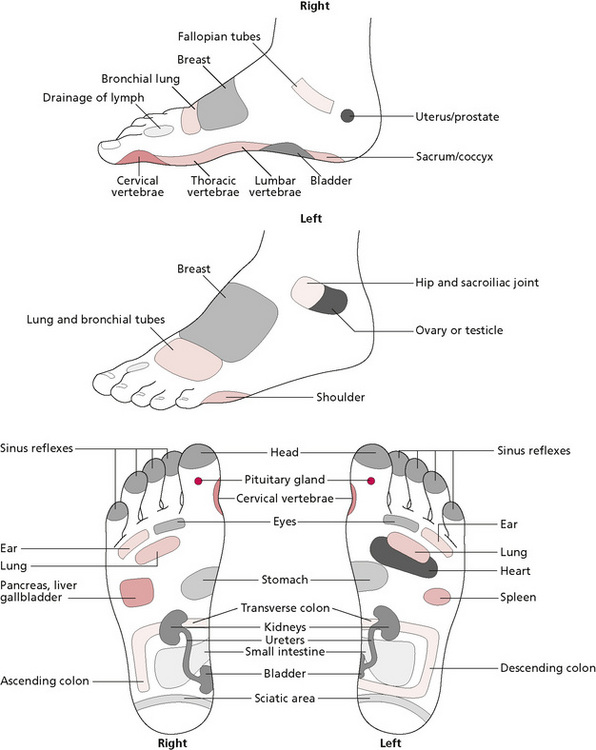

The patient should be side-lying.

The therapist sits behind the patient.

The therapist's thumbs are flexed, the nails placed together and the tips hooked under the subcutaneous tissues at their insertion into the sacral border (Figs. 9.1E, F).

The therapist's fingers are spread over the skin, which they pull gently towards the thumbs.

The thumbs are pushed away, towards the fingers, applying a stretch to the fascia, to the end-feel of the movement.

Do not stretch into the end-feel by exerting an over-pressure, to produce a ‘cutting’ reaction.

Proceed the strokes in the following order: along the sacral border, along erector spinae (both edges), along the vertebral border of the scapula and along the greater trochanter.

Manipulation: subcutaneous (unterhaut) technique

Procedure

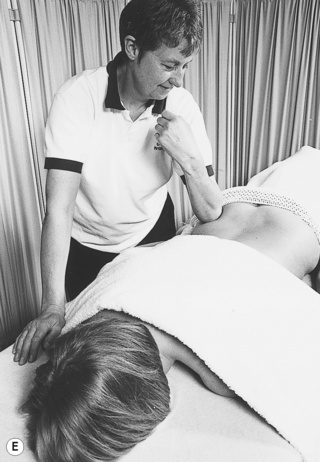

The therapist stands to one side of the patient's trunk.

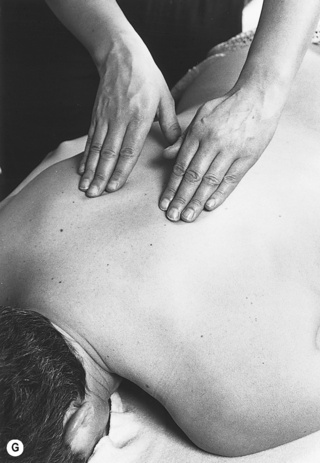

The therapist places the pads of the fingers of both hands lightly on the skin (Figs. 9.1G, H).

The finger pads sink into the subcutaneous layer.

Small pushing movements are made in a cephalad direction.

The skin is moved with the fingers and the stimulus must remain in this layer.

The strokes can be progressed over the area requiring treatment or over an area implicated in a desired reflex effect.

Technique: myofascial release

Features

A stretching technique that recognises and utilises the craniosacral rhythm.

The craniosacral rhythm, believed to be a pulsing of the cerebrospinal fluid, is particularly involved with release of the cranial base, the dural tube and the pelvic and respiratory diaphragms.

Tightening of the myofascia is identified by palpation.

Passive stretching along the direction of the muscle fibres is followed by a hold, until release is felt and the process is repeated until there is no further release.

Somato-emotional release can occur, so it is important that the therapist is qualified to work with and support this release, or functions within a multidisciplinary team.

Procedure

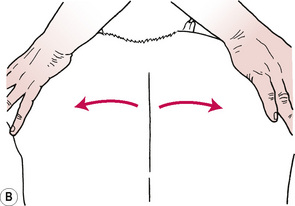

A longitudinal stretch is applied along the direction of the muscle fibres by:

1. Applying the therapist's fingertips on the skin and moving the fingers and underlying skin apart;

2. Placing crossed hands on the skin, exerting pressure through the ulnar border of the hands and separating the hands to stretch the underlying skin (Figs. 9.2A, B);

3. Firmly grasping the limb and pulling along its long axis, the muscle to be stretched dictating the position of the joints (e.g. internal rotation with adduction); and

4. Increasing the localisation of a longitudinal stretch by placing one hand on the proximal border of the muscle under stretch (Figs. 9.2C, D).

Technique: segmentmassage

Features

Effective as a reflex technique.

Works by stimulating the ANS via the skin by a mechanism similar to that of CTM.

It is particularly effective at the maximal tenderness points of CT zones.

It has a more gentle, gradual effect than CTM, working predominantly in the subcutaneous layer but also the fascial layer and the periosteum.

It produces a strong parasympathetic effect and is less likely to produce an adverse reaction.

A wide variety of techniques are included, some of which relate to spinal segments and others to the dermatomes in the limbs.

Assessment of the patient involves stroking segmentally with the thumb tips; a ‘paradoxical reaction’ which leaves white lines rather than the triple response of CTM is produced.

If the skin does not move or react appropriately, vibrations are performed.

Segmentmassage manipulations

The names for these manipulations do not translate easily from the German and this will not be attempted here.

Procedure 1

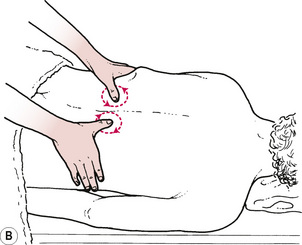

The patient sits on a stool, pelvis tilted forwards to sit on the ischial tuberosities.

The therapist sits behind and places her hands around the patient's iliac crests.

The therapist's thumb tips are placed on the skin on the border of erector spinae and pushed into the muscle layer.

The thumbs are circled away from the spine (Figs. 9.3A, B).

The hands gradually progress in a cranial direction, circling in each spinal segment.

Procedure 2

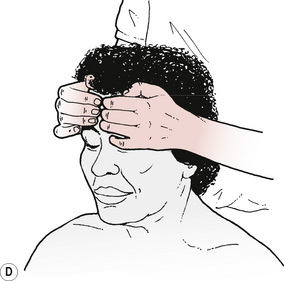

The patient sits on a chair and leans back on to the therapist, who is standing behind.

The patient's head is supported on the therapist.

The therapist places the tips of her fingers on the patient's forehead, with the fingernails of each hand back-to-back (Figs. 9.4C, D).

Small light circles are followed with the fingertips.

The skin should move with the fingers; there should be no glide over the skin.

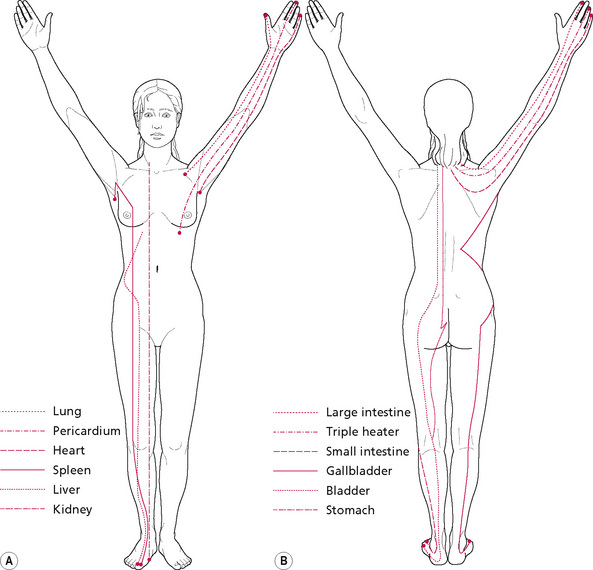

Figure 9.4 • Major meridians of (A) the anterior and medial and (B) the posterior and lateral aspects of the body.

(A) Short dashed line—lung; dash dotted line—pericardium; long dashed line—heart; solid line—spleen; dotted line—liver; dash treble dotted line—kidney. (B) Short dashed line—large intestine; dash dotted line—triple heater; long dashed line—small intestine; dash treble dotted line—stomach; dotted line—bladder; solid line—gallbladder.

Procedure 3

The patient is sitting upright.

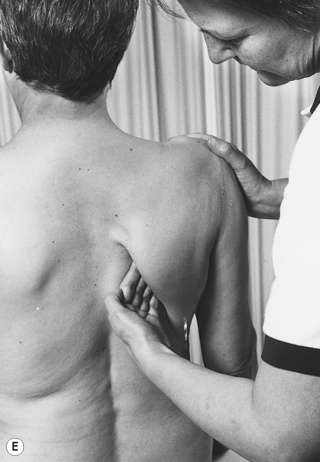

The therapist stands behind and grasps the point of the patient's shoulder.

The other hand slides underneath the scapula, with fingers on teres minor and the thumb under the scapula.

The length of the rhomboid attachment is thumb kneaded (on the periosteum) on the vertebral border of the scapula.

The technique is then modified so that the hand is turned round and small circular movements are applied to the undersurface of the scapula (Figs. 9.4E, F).

Technique: periostealmassage

Procedure

The therapist flexes all the joints of her index finger.

Contact is made between the ulnar border of the proximal interphalangeal joint of the index finger and the point to be treated.

Pressure is increased through this point until the periosteum is reached.

Tiny circular movements are performed with the hand, maintaining the pressure to ensure that the knuckle does not glide over the skin (2 minutes).

Bioenergy therapies

A growing number of therapists incorporate what has come to be known as ‘bioenergy healing’ into their preferred system of massage or touch therapy. This is probably due to an emerging collection of evidence about the biology of human energy. While, historically, more attention has been paid by the medical community to the chemical factors of human biological communication, it is also speculated that electrical and electronic factors may be of equal importance (Oschman 2000a). Clearly, a therapeutic intervention in the nature of bioenergy healing is wholly different in character to the therapies traditionally used in orthodox medicine. It creates a new paradigm in relation to the boundaries of holism.

Very concisely, an accepted explanation of bioenergy healing is that a therapist's intentions can create specific patterns of electrical and magnetic activity in her own nervous system which may interact or influence the electrical and magnetic activity of the patient. The evidence for human energy fields, as with any physical entity, is not in dispute. Seto and co-workers (1992) detected large biomagnetic fields emanating from human hands, confirming the earlier work of Zimmerman (1990). The fields are in the frequency range 0.3–30 Hz, the same frequency as brainwaves. It is well accepted that a 7-Hz frequency of pulsating magnetic fields can stimulate the growth of bone after fracture, an event initiated therapeutically by a medical device. It is thought that similar stimulation can occur with nerves (2 Hz), skin and fibroblasts (15 Hz) and ligaments (10 Hz) (Oschman 2000b), but the relevance of this to therapist/client interaction is not clear but controversial.

Although the proposed mechanism for bioenergy healing is speculative, there are many types of healing intervention being practised where the focus is the therapist's intention to affect, for example in reiki, faith healing, spiritual healing, psi healing, bioenergy therapy and therapeutic touch. These therapies are becoming accepted in mainstream medicine, particularly in oncology and palliative care, albeit for the feeling of well being and hope they induce, rather than any specific bioenergy effect. Their use is justified because of the vast number of reported studies which have shown bioenergy therapies (or ‘healing’) to be effective, thus supplying an evidence base. Benor (1993, 1994) conducted a comprehensive literature review of 131 trials where the standards of research reached modern protocols. Of these trials, 59% reported a statistically significant outcome, considerably more than would have been expected to occur by chance.

Acupressure

Eastern therapies, in particular acupuncture, acupressure and shiatsu, use reflex effects to assist in diagnosis and treatment.

Meridians

In Traditional Chinese Medicine there are 12 major channels (meridians) of the body in which chi (energy or life force) circulates (Fig. 9.4). The meridians are paired and named after the organs with which they are connected: the Lung and Large Intestine; the Stomach and Spleen; the Heart and Small Intestine; the Urinary Bladder and Kidneys; the Pericardium and Triple Heater; the Gallbladder and Liver.

Of each pair, one channel is yin and the other is yang, reflecting the concept of balance between a negative and a positive state of energy. When yin and yang are in dynamic balance this is reflected by a healthy body and mind; if the yin and yang are out of balance this denotes a state of ill-health in the individual.

The channels link together the organs and interact with each other, and there are also regions where they run close to the surface of the body. These superficial regions often coincide with intermuscular or intertendinous depressions, which are easily palpated by a trained therapist. Acupoints are situated along the course of the channels. The points are believed to be three dimensional; that is, not only are they on the surface of the skin but also they extend to a varying depth into the underlying tissues. They also have a different electrical resistance to that of the surrounding tissue. The significance of the acupoints is that they offer a means of access to the channels, the energy of which can then be altered by the application of various treatment modalities, for example needling, finger pressure, electrical current, laser or moxibustion.

Although there is a lack of definitive evidence (in Western terms) for the existence or non-existence of the channels, there is a growing body of research which supports claims that stimulation of acupoints can cause neurohumoral and chemical changes. For example, it has been shown that stimulating acupoints produces significant analgesic effects when compared with non-acupoints (Chapman et al 1977); stimulating an acupoint near the wrist can reduce nausea and vomiting in postoperative patients (Dundee et al 1986).

Acupuncture is being used increasingly by Western orthodox medical practitioners to relieve pain. It is thought both to influence the pain-gate mechanism and to provoke the release of analgesic endogenous opiates.

It has been found that ohmic resistance is generally lower over acupoints in relation to surrounding areas of skin. The phenomenon is used by practitioners of Ryodoraku acupuncture therapy, based on the belief that the points of high conductance correspond with increased excitability of sympathetic nerves. There is, however, some disagreement as to the significance of the difference in electrical conductance, as this can also be influenced by autonomic arousal. (Chinese researchers have found a correlation between acupoints and nerves.)

Although complete mechanisms have not yet been found for the changes produced by stimulation of acupoints, there is a vast body of empirical evidence which supports its clinical effectiveness.

Practice

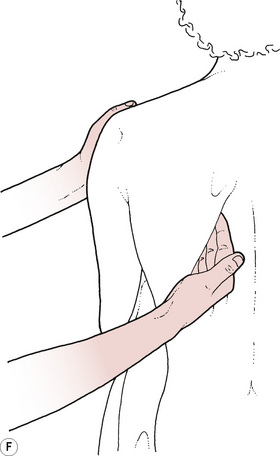

The therapist should at least be aware that there are many types of reflex points suggested by various schools of medicine; she should be wary of their presence and the possible effects of manipulating them. Alternatively, having assessed the individual patient and made decisions concerning treatment goals, she may choose a specific type of reflex massage with the intention of having a wider physiological and therapeutic effect, rather than a purely local mechanical effect. For example, she may also choose to incorporate their therapeutic power as an integral part of a massage treatment, as in massaging the reflex points of the feet (reflexology) for a combined local mechanical and broader reflex effect (see Fig. 9.9).

Acupressure is another example of a therapy that was brought to the West from the East. Early Chinese texts indicate that the practice of applying finger pressure to points on the body predates the practice of acupuncture.

The technique is variously described as Chinese micromassage, pressing the Tsubo (shiatsu) or acupressure. Although the philosophies and practices differ, they all have in common a system of channels (meridians) and the manipulation of points along the channels to effect a change in the balance of energy. The different schools advocate various methods of manipulation and some propose that the channels should be tonified or sedated, depending on the diagnosis, which may be of either excess or deficient yin or excess or deficient yang. The yin-yang theory is based on the belief that all qualities contain the potential of their opposite. Yin is associated with such attributes as passivity, cold and rest, whereas yang is associated with activity, heat and stimulation (Kaptchuk 1983). When yin and yang are in balance, a person is presumed to be in an optimum state of health; conversely, a state of ill-health exists when they are out of balance. Most systems agree that, in a condition where yin is depleted, the treatment should be aimed at tonifying; this is done by working along the channel in the direction of the energy flow, using slow and gentle pressure. If the condition is thought to be yang, sedation is the aim of treatment; this is achieved by working against the flow of energy more quickly and with greater pressure.

The therapist usually uses the pad of a finger or thumb to apply the pressure. Some writers maintain that this is because there is a relative electrical neutrality at the end of the digit, being the location where yin and yang are in equilibrium (Lavier 1977). Whether or not this is so, the digits are clearly the tools of choice. However, on regions of the body covered by thick muscular or fascial layers, and which do not have a low pain threshold for pressure, an elbow or knuckle may be used to apply the pressure, which should always be within the tolerance of the patient. As with acupuncture, the aim of treatment can be to reduce pain, to alleviate symptoms of disease and to promote a balance for maintaining or restoring health. Acupoints should not be overtreated and it is generally recommended that local points be pressed for up to 1 minute, while more distal points may be held for up to 3 minutes.

Cautions and contraindications

Caution is required when working with acupoints because of the potential reflex effects. If acupressure is used as a method of pain relief in musculoskeletal disorders, the therapist should be aware of the possibility of stimulating complex visceral and autonomic effects. For this reason, acupressure should not be used for patients with heart disease and other serious visceral disorders. Neither should it be used for the treatment of any disease state unless the therapist is appropriately qualified.

Manipulation: acupressure

Procedure

There is no requirement for the patient to remove clothing for acupressure. However, if the therapist relies on palpation to find the points, clothing should be removed.

Method 2

The therapist uses the pad of the finger or thumb and, keeping contact with the skin, makes very small rotary movements (Figs. 9.5A, B).

Method 4

Over thick muscular or fascial layers, the therapist may use a knuckle (Figs. 9.5C, D) or the elbow (Figs. 9.5E, F) to apply pressure.

Location of acupoints

Due to individual anatomical variation some of the locations of acupoints are best described with reference to the cun. This is a unit of measurement based on the patient's anatomy. Thus, 1 cun is the distance between the creases of the distal and the proximal interphalangeal joint of the patient's middle finger (the length of the middle phalanx of that finger). The breadth of the index and middle finger, at the level of the distal interphalangeal joint when the fingers are adducted, is 1.5 cun. The breadth of the patient's four fingers, at the level of the proximal interphalangeal joint when the fingers are adducted, is 3 cun.

The following are points commonly used in acupressure massage.

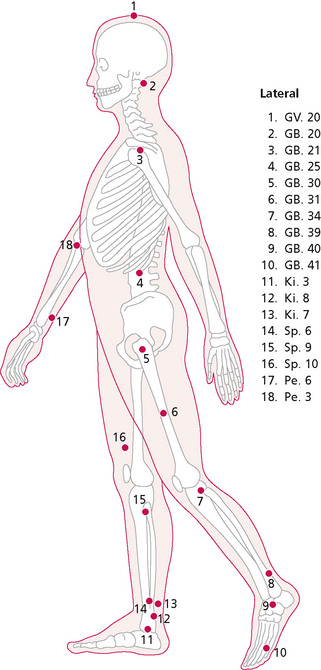

Lateral View (Fig. 9.6)

GV 20

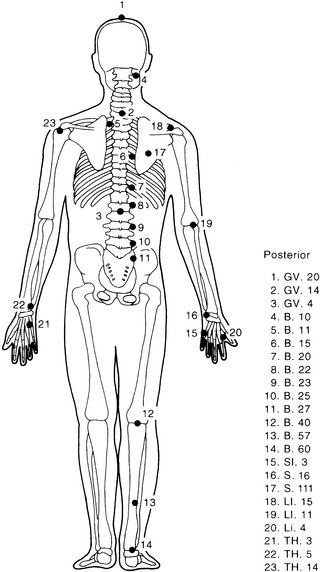

Posterior View (Fig. 9.7)

GV 14

Bl 60

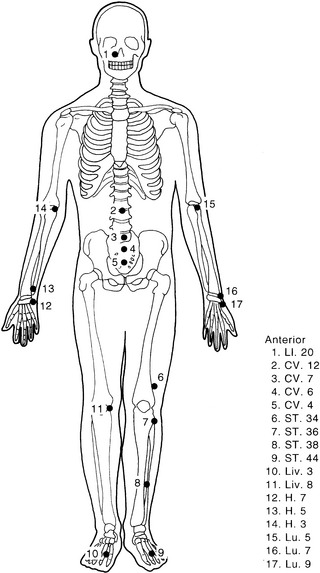

Anterior view (Fig. 9.8)

LI 20

Technique: reflextherapy

Purpose

Reflextherapy is also an example of an ancient therapy which originated in the East. It is known variously as reflextherapy, reflexology or zone therapy. Reflexologists believe that each area of the body is represented by zones on the feet and that the feet can be used as a diagnostic tool to uncover imbalances. The therapist treats the relevant area to produce a reflex response in the connected somatic area (see Fig. 9.9).

Two studies have examined reflexology as a diagnostic tool. Baerheim et al (1998) engaged three reflexologists to find the clinical problems of 76 patients by examination of the soles of the feet. Inter-rater agreement, measured by weighted Kappa, was significantly better than chance for six parts of the body but was too low to be of clinical significance. White et al (2000) investigated whether reflexology charts could be used as a valid method of diagnosis. Two reflexologists examined 18 patients with six specified clinical conditions. The therapists were blinded to the conditions and rated the probability that each of the six conditions were present. Inter-rater reliability scores were very low, providing no evidence of agreement between examiners. The researchers concluded that this method of diagnosis was very poor at distinguishing between the presence and absence of medical conditions. Blood flow has been examined in two further studies. Using Doppler sonography, blood flow changes in the right kidney were measured in a placebo controlled double-blind, randomised study. One group of 15 adults were given reflexology on the zone of the right kidney; the control group had reflexology on other foot zones. There was a significant difference between groups with the kidney group showing an increase in renal blood flow (Sudmeier et al 1999). Support is given to the findings by Mur et al (2001). Here the treatment group (n = 16) received foot massage on the intestinal zone, while the placebo group (n = 16) had foot massage on unrelated zones. Blood flow velocity in the superior mesenteric artery and a resistive index as a parameter of vascular resistance were calculated. During treatment there was a significant reduction in the resistive index for the treatment group, suggesting an increase in blood flow in the superior mesenteric artery and the subordinate vascular system.

Reflexology has been found to significantly decrease premenstrual symptoms (Oleson & Flocco 1993) and to decrease anxiety in patients with breast or lung cancer who were on a medical oncology unit. In the latter study, the patients with breast cancer also experienced a significant reduction in pain. Degan et al (2000) found that of 40 patients with pain associated with a lumbar-sacral disc herniation, 62% reported a reduction in pain after three sessions of reflexology. This supports the earlier work of Kovacs et al (1993) with patients who had low back pain. After reflextherapy they showed significant improvement in pain scores.

Two contrasting studies have examined the role of reflexology in bronchial asthma. Brygge et al (2001) gave 10 weeks of either active or placebo reflextherapy to two groups of 20 with bronchial asthma in a blind, controlled trial. Objective lung function tests did not change for either group; beta2 inhalation and quality of life scores improved in both groups with no significant difference between them. This is at odds with a study by Hui-Xian (1994) in which it was reported that all 45 children with bronchial asthma showed improvements in symptoms after reflexology. These two studies clearly demonstrate the value of controlling for placebo. Frankel (1997) examined the effect of reflexology on baroreceptor reflex sensitivity (BRS), blood pressure and sinus arrythmia. There were two experimental groups, one receiving reflexology and the other foot massage, plus a control group. Both experimental groups showed a decrease in BRS and an increase of over 30% in frequency of sinus arrythmia compared to the control. This may indicate that simple foot massage could be as effective as reflexology in certain conditions but further research is needed. A recent German paper has raised the issue that reflexology is not always beneficial. The researchers investigated the possible usefulness of foot reflexology on recovery after a surgical intervention. A total of 130 patients who had undergone abdominal surgery for gynaecological reasons were given reflexology. The authors concluded that reflexology is not recommended for acute, abdominal post-surgical situations in gynaecology because it can trigger abdominal pain (Kesselring 1999).

Features

The zones of the feet are usually pressed gently with the thumb or fingers of the therapist. Some writers advocate deeper pressure with a knuckle if this is thought appropriate.

Baerheim A., Algroy R., Skogedol K.R., et al. Feet a diagnostic tool? Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen.. 1998;118(5):753-755.

Benor D.J. Healing research. vol 1. Deddington: Helix; 1993. Cited in:Charman R.A., editor. Complemenary therapies for physical therapists. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

Benor D.J. Healing research. vol 2. Deddington: Helix; 1994. Cited in:Charman R.A., editor. Complementary therapies for physical therapists. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

Brygge T., Heinig J.H., Collins P., et al. Reflexology and bronchial asthma. Respir. Med.. 2001;95(3):173-179.

Chapman C.R., Chen A.C., Bonica J.J. Effects of intrasegmental electrical acupuncture on dental pain: evaluation by threshold estimation and sensory decision theory. Pain. 1977;3(3):213-227.

Degan M., Fabris F., Vanin F., et al. The effectiveness of foot reflextherapy on chronic pain associated with a herniated disc. Prof. Inferm.. 2000;53(2):80-87.

Dundee J.W., Chestnut W.N., Ghally R.G., et al. Traditional Chinese acupuncture: a potentially useful antiemitic? Br. Med. J.. 1986;293:583-584.

Frankel B.S. The effect of reflexology on baroreceptor reflex sensitivity blood pressure and sinus arrythmia. Complement. Ther. Med.. 1997;5(2):80-84.

Haase H. Bindegewebsmassage Wirkungsphysiologische grundlagen und methodik. Zschr Artzl Fortbild. 1962;62(13):134-136.

Holey L.A., Watson M. Inter-rater reliability of connective tissue zone recognition. Physiotherapy. 1995;81(7):363-369.

Hui-Xian. A clincial analysis of foot reflex massage for the treatment of 45 cases with infant bronchial asthma. AOR Research Reports, fourth ed. Henfield: AOR, 1994.

Kaptchuk T.J. Chinese medicine: the web that has no weaver. London: Rider, 1983.

Kesselring A. Foot reflexology massage: a clinical study. Forsch. Komplementarmed.. 1999;6(Suppl. 1):38-40.

Kovacs F.M., Abraira V., Lopez-Abente G., et al. Neuro-reflextherapy of non specified low back pain. AOR Research Reports, fourth ed. Henfield: AOR, 1993.

Lavier J. Chinese micro-massage. Wellingborough: Thorsons, 1977.

Mur E., Schmidseder J., Egger I., et al. Influence of reflex zone therapy of the feet on intestinal blood flow measured by color doppler sonography. Forsch. Komplementarmed.. 2001;8(2):86-89.

Oleson T., Flocco W. Randomized controlled study of premenstrual symptoms treated with ear hand and foot reflexology. Obstet. Gynecol.. 1993;82(6):906-911.

Oschman J.L. Energy medicine—the new paradigm. In: Charman R.A., editor. Complementary therapies for physiotherapists. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

Oschman J.L. Energy medicine: the scientific basis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Seto A., Kusaka C., Nakazato S., et al. Detection of extraordinary large biomagnetic field strength from human hand. Acupuncture Electrotherapeutics Research Int Journal. 1992;17:75-94. CitedOschman J.L., editor. Energy medicine: the scientific basis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Sudmeier I., Bodner G., Egger I., et al. Changes of renal blood flow during organ-associated foot reflexology measured by color Doppler sonography. Forsch. Komplementarmed.. 1999;6(3):129-134.

White A.R., Williamson J., Hart A., et al. A blinded investigation into the accuracy of reflexology charts. Complement. Ther. Med.. 2000;8(3):149.

Zimmerman J. Laying-on-of-hands healing and therapeutic touch: a testable theory. BEMI Currents Journal of the Bio-Electro-Magnetics Institute. 1990;2:8-17. Cited in:Oschman J.L., editor. Energy medicine: the scientific basis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.