11 Massage for people with long-term and terminal illness

Long-term conditions present specific problems and therefore require that health care workers take an appropriate approach. Patterns of progression may differ and these conditions may be chronic but stable, or may deteriorate, as, for example, in motor neurone disease. Alternatively they may exacerbate and remit, as with multiple sclerosis, for example. In terminal illnesses, progress may be either slow or rapid from the time of diagnosis.

Common to all these conditions is distress, fear, stress, unavoidable symptoms and a severe disruption of lifestyle. In all cases, health care workers should emphasise the maintenance of quality of life (QoL) for these patients, reducing stress and supporting the patients by equipping them with coping strategies. If cure is not an option, then acceptance and learning how to cope and maintain independence are the challenges facing patients and their carers. Carers are an integral part of the process and helping the patient to maintain close supportive relationships is important.

Although the difficulties and emotional trauma must not be minimised in any way (these diagnoses are clearly devastating and the trauma not fully appreciated by anyone without personal experience), care should be directed towards assisting patients and those close to them through this time in shared experience, rather than feeling they are under an impossible burden. Thus, goals are not focused on cure or passive receipt of care but on patient-led strategies and therapies which respect and involve their personally identified unit of significant others.

• Reduce musculoskeletal symptoms;

• Desensitise hypersensitive skin;

• Help prevent pressure sores;

Massage may therefore be an obvious choice as a useful and often powerful tool when working with this client group, as it can help in the ways listed above. It should be stressed, however, that the problems faced by this client group are complex—massage by itself cannot achieve these effects but it can make an important contribution to all of them.

Massage for people with cancer

Patients with cancer often endure a long period of anxiety and uncertainty as they wait for diagnosis, medical test results, unpleasant drug treatments, sometimes disfiguring surgery and new prognoses. Their physical fight against the disease may be accompanied by emotions such as denial, fear, anxiety, sorrow and loss. They may have to let go of work, leisure pursuits and loved ones at the same time as they endure pain and sometimes disablement. A stress management programme incorporating health education, muscle relaxation and massage has been found to be helpful in reducing stress in people with cancer (Lin et al 1998). A systematic review conducted by Fellowes et al (2004) concluded that short-term benefits may be conferred by massage and aromatherapy on psychological well being, and possibly anxiety, but evidence is mixed. A later review by Wilkinson et al (2008) concluded that further well-designed and large trials were necessary to draw firm conclusions in relation to massage in cancer management. Billhult et al (2008) found that, in a sample of 22 women with breast cancer who were undergoing radiotherapy, effleurage massage had no effect on circulating lymphocytes, or the degree of anxiety, depression or QoL. The radiation department as the study environment may have influenced these results.

Modern medicine can sometimes cure cancer and can offer considerable relief from symptoms. This section relates more specifically to the terminally ill patient who may be at home, in hospital or in a hospice. Massage has been found to be beneficial in reducing perceptions of distress, fatigue, nausea and state anxiety in cancer patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplant (Ahles et al 1999). A randomised controlled clinical trial, which was conducted within a hospice, examined the effects of massage on cancer pain intensity, prescribed intramuscular morphine equivalent doses (IMMEQ), hospital admissions and QoL. Pain intensity was significantly reduced after the massage and current QoL scores were significantly higher in the massage group. IMMEQ doses were comparable in the massage and control group, as were hospital admissions (Wilkie et al 2000). These two studies underscore the benefit of massage in both hospital and hospice environments with patients at different stages of disease.

Relationships with carers are crucial at this stage, as they offer love, support and intimacy to the patient. It is important, then, that therapeutic intervention helps to strengthen relationships rather than disrupt them. Touch can be a strong need of the cancer sufferer, who may have lowered self-esteem, particularly if disfiguring surgery has been necessary. Touch may also be important for carers, as something they can give to the patient, ‘something to offer’ that is positive and therapeutic, enabling them to take an active role rather than one of passive observation which can lead to feelings of helplessness and uselessness. It has positive benefits as a supportive care intervention (Hughes et al 2008) and can be applied safely (Corbin 2005). If a carer wishes to learn massage a good starting point would be for the therapist to instruct him/her in how to give a foot massage. There is evidence that a 10-minute foot massage (5 minutes each foot) can have a significant effect on perceptions of pain, nausea and relaxation (Stephenson et al 2000). A further study has examined the effects of foot reflexology on anxiety and pain in patients with breast or lung cancer who were on a medical/ oncology ward. All the patients treated with massage experienced a significant decrease in anxiety and patients with breast cancer showed a significant decrease in pain (Stephenson et al 2000).

Touch can also help to restore intimacy, which may be lost due to fear of hurting the patient, or because of separation through periods of medical treatment. Touch itself, as well as massage, may have immediate beneficial effects on pain and mood (Kutner et al 2008), so the deprivation of touch may be very significant. The therapist must work with those close to the patient, and must sometimes relinquish her role and pass it on to the carer. Carers may also be stressed and in need of massage themselves, in which case ‘time out’ should be encouraged. Another option is reciprocal massage, between patient and carer, which may facilitate communication and intimacy. It can be a non-strenuous but fulfilling form of sensuality. It may restore the early experiences in a relationship—exploration, physical awareness and gentle, sensitive responses to each other's needs. Scented oils and music may enhance the experience. The advice and support of the therapist may facilitate this activity. The relaxation effects of massage can also aid in reducing sleep disturbance (Richards 1998).

McCaffery and Wolf (1992) suggest that massage is especially helpful when the patient is confined to bed (either because of specific treatment or the terminal stage) and lies supine much of the time, as it improves circulation to the skin and reduces skin breakdown. This can enhance nursing strategies to reduce pressure sores such as turning and positioning regimens. Care should be taken if the skin has become reddened, as this can indicate that there is tissue breakdown underneath the skin, and manipulation of skin may worsen the situation.

Modifications usually make a treatment possible and it is always worth pursuing, as a study with female cancer patients showed that massage gave them ‘meaningful relief from suffering’ (Billhult & Dahlberg 2001).

Patients should be respected as individuals and encouraged to direct the best time for the massage and how long it should last, and to decide whether the massage should be conducted in silence or whether it offers a welcome opportunity for talking, either general discussion or expression of feelings. The areas to be massaged may be modified by the presence of any open lesions. The hands and feet may be good options if accessibility to other parts of the body is limited by surgical wounds, drips or drains. These areas are often acceptable to the individual who does not welcome further personal intimacy. The addition of an essential oil to the lubricant may enhance the effects of massage. Wilkinson et al (1999) found that the addition of Roman chamomile essential oil to a carrier oil enhanced the therapeutic effects of reduced anxiety and improved overall QoL. A follow-up RCT study of 288 cancer sufferers found no long-term benefit on anxiety or depression, but a clinically important benefit up to 2 weeks after the intervention (Wilkinson et al 2007).

Is massage a safe intervention for people with cancer?

Early writers on massage placed little emphasis on cancer as a contraindication to massage. It was not listed by Goodall-Copestake (1926) or Tidy (1932), although this omission could indicate the scant attention the disease received generally in physiotherapy texts. Hollis (1987) gives tumour as a contraindication and Tappan (1988) lists melanoma, as this type of cancer metastasises easily through lymphatic and blood vessels. In its traditional use, within orthodox medical care, massage has previously been regarded as being contraindicated for patients with active malignant disease.

Physiotherapists, by taking a detailed medical history and having access to patients' medical records, have avoided techniques that might increase local metabolic rate or blood flow in the vicinity of active disease. This statement needs some clarification, as massage has been used to reduce local symptoms, or to aid relaxation in the terminally ill patient, when emphasis is on comfort rather than cure. Massage has also proved useful, for example, in spinal cancer which has produced uncomfortable sensory changes such as hyperaesthesia. This can be sufficiently severe to make touch uncomfortable to the point where washing becomes distressing. Gentle rhythmical stroking can prove useful for desensitising the skin, and the use of warm water for massaging the skin gently (via gentle movements in a hydrotherapy pool, for example) may be helpful. Heavier stroking can be used as a counterirritant, acting through the pain gate to reduce pain. Also, after radical mastectomy for example, patients can be given or taught oedema massage for the arm following removal of the lymph glands. Effleurage was formerly the main treatment of choice; it has now largely been superseded by the more superficially applied manual lymphatic drainage. Traditionally, however, massage has been taboo in the earlier active stages of the disease, but acceptable at the later and terminal stages.

Of course, patients with cancer have the right to treatment of other injuries and physical problems unrelated to the cancer. They also have the right to support for symptoms of stress, and help with coping mechanisms. Thus, as long as the tissues are not actively manipulated over any active disease site, an increase in lymphatic and venous flow is avoided in patients with melanoma or Hodgkin's disease and the lymph nodes are not directly stimulated mechanically, then massage can be a useful adjunct to other therapies. Stationary and light pressure techniques are probably the safest (holding, therapeutic touch, acupressure, for example); the more superficial techniques—as used in gentle stroking, whole body sedative massage or through an oily medium—would be the next treatment of choice from a safety viewpoint. It is unlikely that these techniques would be physiologically more stimulating than everyday activities such as walking or housework. Hadfield (2001) used aromatherapy massage in patients with a primary malignant brain tumour who were attending their first follow-up appointment after radiotherapy. There was a statistically significant reduction in four physical parameters of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) which suggested a relaxation response.

In relation to drug therapy, it has been suggested that massage may increase the rate at which chemotherapeutic agents flow around the body when administered into the bloodstream, that it increases the rate at which drugs enter the bloodstream when administered by other means and that the dosage should be reduced accordingly (McNamara 1994). However, this has not yet been substantiated experimentally. Also, it has been suggested that massage increases the rate at which chemotherapy and its toxins will be lost from the body, although it should be recognised that we have insufficient experimental evidence to support these suppositions. Of course, as in all conditions, techniques and approaches should be modified to match the stage of disease.

Another pertinent study was undertaken by McNamara (1994). She sent out questionnaires to 24 volunteer massage practitioners and asked for their views and knowledge on the use of massage for people with cancer. The main findings in relation to dangers and contraindications were that practitioners had often been taught or had read that massage was contraindicated in the earlier stages of the disease but not in the terminal stages. There was obviously some concern about the lack of research evidence to support or refute this suggestion, but massage was generally being offered to people with cancer.

An absolute contraindication for massage is undiagnosed cancer. It is important that the massage therapist is alert to the possibility and that any patient experiencing symptoms which may relate to a serious condition should be urged to seek advice from a doctor immediately. Look for:

• Intractable pain—no relief on rest, significantly disturbed sleep (this may indicate inflammatory or malignant disease);

• Feeling of being generally unwell;

• Inflammation and heat in the absence of trauma;

• Unexplained weight change; and

• Any lump bigger than 5 cm, especially if it is a recurrence of a previous lump or is deeper than fascia or is increasing in size (Grimer & Dalloway 1995).

Within the physiotherapy profession there has been a long tradition of concern about the safety of massage for patients with cancer. Its unwritten nature leaves an apparent controversy in this area, which has prompted research in the subject (McNamara 1994). The consensus is that massage is not acceptable if:

• The cancer is metastasising;

• The massage is in the region of a contained tumour;

• The therapist is not sensitive to any fragile areas of bone.

Generally, massage is considered quite appropriate for use in the terminal stages of the disease.

If a therapist is unsure of any of these factors and is unable to receive specific guidance from the patient's doctor, then she should err on the side of caution.

If in doubt, stationary holding or therapeutic touch techniques can be used as there is no evidence to suggest that these are unsafe in any circumstances.

Gentle stroking, a back rub, foot massage or whole body massage are techniques of choice for relaxation.

Heavier stroking or classical Swedish massage techniques can be used to influence the pain gate or to have a counterirritant effect to relieve pain.

The reflex techniques of acupressure may be preferred, to promote relaxation or for their balancing effect to strengthen immunity and improve general health.

Massage should be modified to match the medical condition and desires of the individual patient, and the type of massage and structure of the sessions negotiated beforehand. Essential oils may be found to be pleasant, or they may worsen nausea. If tolerated, specific oils, such as rosemary, can be applied as a shampoo to the head or as a massage oil, to stimulate hair growth following chemotherapy. If applied in excess, however, it may cause convulsions and fitting, so the therapist should be cautious. Massage may be preferred for a whole hour or may be tolerated only for short periods of time.

Tyler and colleagues (1990) demonstrated that the 1-minute back rub (a traditional nursing procedure) showed no statistically significant worsening of mixed venous oxygen saturation and heart rate levels when applied to 173 patients in receipt of critical care. This suggests that massage is safe even in critically ill patients, though the considerable variability shown reinforces the principle of close monitoring of physiological responses in this client group. Dunn et al (1995) also found that massage and aromatherapy with lavender oil did not adversely affect vital signs in patients being nursed on an intensive care unit. Stress or coping measures were not altered to statistically significant levels post-massage, or aromatherapy, or rest; but aromatherapy significantly improved mood and decreased anxiety levels.

Oedema in oncology

A specific use of massage is in the treatment of oedema. Hydrostatic oedema may result from the pressure of a malignant growth, whereas lymphoedema may be caused by the removal of lymph glands during cancer surgery or their obliteration by radiotherapy or tumour mass, and may occur in Kaposi's sarcoma, associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). This oedema is protein rich and must therefore be removed by the lymphatic system.

To summarise, the principles of treating hydrostatic oedema are to clear proximal areas first; thence to direct strokes from distal to proximal; increase pressure in the tissue spaces; and supplement massage by elevation of the limb, compression and circulatory exercises. The principles of lymphoedema treatment are that massage is light in order that lymph vessels, which are placed superficially in the tissues, are stimulated; healthy glands are stimulated first, before clearing trunkal areas; swelling is then drained into these cleared areas before being moved towards healthy glands; and massage is accompanied by compression bandages, exercises and benzopyrone therapy for maximum effect. Manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) is the technique of choice for lymphoedema. The selection of strokes includes stationary circles, light effleurage, pump technique, scoop technique and rotary technique, which can be applied with a little oil. The effectiveness of this regimen in the treatment of lymphoedema has been demonstrated by Bunce et al (1994), who studied 25 women referred for post-mastectomy lymphoedema treatment. Massage (Foldi MLD), pneumatic compression, compression bandaging and exercises were undertaken for 3 hours daily, 5 days per week for 4 weeks. The length of time since mastectomy was found not to affect the results. After the intensive phase of treatment, there was a mean reduction in excess volume of the affected limb of 40%. At 12 months, the affected limbs were no more than 5% larger than the unaffected limbs. The results in this well-designed study were statistically significant.

Massage for lymphostatic oedema

Lymphoedema is swelling due to an abnormality in the lymphatic system, often occurring in one limb. It is classified according to cause.

Primary lymphoedema

Secondary lymphoedema

Parasitic lymphoedema is caused by filarial parasites, transmitted through mosquito bites. The parasites block the lymphatics causing massive oedema and large skin vesicles, when it is often called elephantiasis.

Iatrogenic lymphoedema results from surgical removal or radiotherapeutic destruction of the glands in the treatment of cancer.

Additionally, obliterative lymphangitis can occur secondary to deep vein thrombosis, trauma can damage vessels or glands, and kinetic insufficiency can occur in paralysis.

Lymphoedema is also classified according to severity (Casley-Smith & Casley-Smith 1992, Foldi 1994):

Grade 1: Pitting oedema which reduces on elevation.

Grade 2: No pitting or reduction on elevation; fibrosclerosis, which may feel hard; skin changes.

Traditional techniques for the removal of excess tissue fluid, such as deep massage, electrical stimulation under pressure, compression devices and muscle pump exercises, have been used with variable results in this condition. The current treatment of choice is a regimen termed complex physical therapy (CPT) or complex decongestive physical therapy (CDP), which is time-consuming and therefore costly, but which achieves excellent results. An integral part of the regimen is the specialised massage technique of MLD, which was originally developed by Vodder (1936) and has since been modified by Leduc (Leduc et al 1981) and Foldi (1994) (see also Chapter 9).

MLD is thought to be preferable to other forms of massage in the treatment of lymphoedema as it is based on the anatomy and physiology of the lymphatic system and deeper forms of massage are thought to damage the lymphatics. Rapid massage at a pressure of 70–100 mmHg has been found to create artificial cracks in lymphatic vessel walls, loosen subcutaneous tissue, form large tissue channels and release lipid droplets (Eliska & Eliskova 1995). The massage in this study, however, was particularly vigorous.

Manual lymphatic drainage

Aims

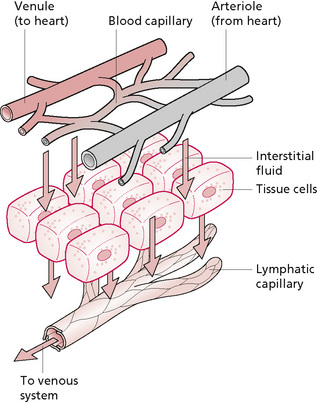

To stimulate lymphatic drainage (Fig. 11.1) and to clear proximal lymphotomes (adjacent areas of the trunk).

To promote movement of lymph across lymphatic watersheds.

To open up superficial collateral lymphatic vessels.

To facilitate lymph removal by opening up the flaps in the vessel walls.

To stretch and assist in the reabsorption of fibrous tissue.

Principles

Lymphatic oedema cannot be removed via the bloodstream as it is protein-filled. The plasma proteins are too large to be reabsorbed through blood vessels, so must be removed via lymph channels. If the lymphatic system is poor, the proteins will increase the colloid osmotic pressure in the tissue spaces, drawing fluid out of the bloodstream. This results in massive oedema. Fibrin is formed which traps the swelling, and the cells are separated from their source of nutrition. The skin becomes hard and altered in quality. Compressive techniques do not open the flaps in the walls of lymphatic vessels, to allow fluid in. Massage should therefore gently move the skin, opening the flaps in the superficial vessels and have a pumping effect on the deeper vessels. It should also bypass the damaged vessels and facilitate removal across the lymphatic watersheds. Massage should be given for 1 hour daily. It should not be undertaken in the presence of untreated acute infection (cellulitis) and reddening of the skin must be avoided, as histamine is thought to increase oedema (Kurz 1989, 1990).

Strokes

Treatment should start in the left supraclavicular space, to drain the ductus thoracicus followed by clearance of the adjacent lymph gland area (axilla or groin) (Kurz 1989, 1990). If the lymph glands are removed or damaged, the strokes should sweep across to the glands on the opposite aspect of the body. For example, if the oedema is in the arm and the axillary glands have been removed during mastectomy, the massage should continue to the opposite axilla. In severe cases it may be necessary to clear the opposite side of the trunk and adjacent quadrants on the opposite side of the trunk before moving towards the affected limb. Once the starting point has been decided, the areas of treatment must progress by clearing proximal areas before distal. The massage cannot continue across a scar: it should progress on the opposite aspect of the body.

Self-care

The patient should be advised that MLD is only one component of a complex programme of treatment. Treatment is much more effective if the patient conscientiously follows the regimen of prescribed benzopyrones (a form of vitamin P which causes resorption of the tissue proteins), pressure garments, measured to a precise fit and worn 24 hours a day, and skin care. Mechanical pumps may occasionally be used in secondary lymphoedema under supervision, but should be used judiciously. If used in primary oedema, they merely shunt the swelling to a proximal area, for example the genital region. They can also result in the formation of a fibrous band around the top of the limb, which reduces the effectiveness of other treatments.

When severe, the fluid can sometimes be felt to ripple in the tissues under the therapist's hand. Aching within the trunk, for example over the thoracic spine area, often reduces as the swelling reduces.

Progress can be monitored by measuring the girth along a limb, every 10 cm, with a tape measure. The volume of the limb is then calculated by dividing the limb into four, then adding the volumes of each segment using the formula for a cylinder (volume = π (circumference/2π) 2h, where circumference is the mean of adjacent circumferences and h is 100 mm).

Effectiveness of massage in oedema

Some time-consuming techniques have been described here. Just how effective is massage in oedema? Ladd et al (1952) examined the effects of massage on lymph flow. They cannulated the lymph channel in the neck of 17 dogs and collected lymph in a test tube during an experimental procedure. The nearest limb of each dog was put through a routine of massage, passive movement and electrical stimulation interspersed with 10 minutes' rest, the whole cycle being repeated between two and four times and rotated in order between dogs. The massage was a modified Hoffa-type routine of stroking, effleurage, petrissage and Hoffa frictions, and it was found to raise lymph flow to significant levels above those found in the other techniques. Passive movements worked better than electrical stimulation. Of further interest was the finding that, in one dog which shivered, lymph flow was as good as when massaged. This mirrors the findings of Wakim and co-workers (1949) that blood flow is increased more by active movement than passive movement or massage, suggesting that in normal healthy individuals massage is not required to improve certain physiological parameters. This does not, of course, negate its use for psychological or musculoskeletal benefits.

In 1990, a study was conducted in which Mortimer et al measured skin lymph flow by an isotope clearance technique in anaesthetised pigs. It was found that the flow rate varied naturally between pigs and between parts of the body, and that subdermal flow was faster than deep flow. Local massage, described as ‘Gentle, local massage using a hand-held massager’ increased flow rates to highly significant levels statistically. These results are interesting, because they suggest that local mechanical manipulation of the tissues will increase the lymphatic flow. It can be postulated that this is due to a mechanical movement of the tissues opening the flaps in the lymphatic vessel walls, to allow passage of the proteinous fluid. Further evidence was provided by Ikomi & Schmid-Schonbein in 1996. They measured the effects of passive leg movement and massage on lymph flow rates in a dog and found that both movement and massage increased the rate of lymph flow. The rate was dependent on the frequency of tissue movement and the amplitude of skin displacement. These results were independent of heart function, indicating that expansion and compression of the lymphatics provide a mechanism for the pumping of lymph.

There is much interest in the specific effectiveness of MLD. One such study was undertaken by Kurz (1989, 1990) who gave MLD (Vodder method) to 29 patients suffering from lymphoedema due to varying causes. The results were compared with those of 10 healthy controls. It was found that three to four times the quantity of urine was excreted after the massage. The subjects underwent controlled food and drink intake before the study and full urine analysis was conducted after the massage phase. The significant findings were that urine levels of 17-OH-cortisone and serotonin decreased, whereas those of adrenaline (epinephrine) increased by 50% and histamine by 129%. The authors found the results elucidating in that cortisone is sodium retaining and oedema producing, so its elimination will have obvious effects on oedema. The reduction in serotonin levels demonstrates destruction of this oedema-producing hormone. The researchers thought that the increases in adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) were due to the fact that they were stimulated to increase the circulation, and that the presence of large quantities of histamine indicates that this might contribute to the oedema formation as it creates and sustains tissue fluid. They consider that this research substantiates Kuhnke's (1975) claims that MLD causes reabsorption of oedema, contraction of vascular muscle (as shown in the catecholamine levels) and decompression of nociceptors (as evidenced by the reduction in the concentration of serotonin and other metabolites). This research, however, did not have an experimental and control group equal in size and the explanation for the meaning behind the urine analysis is speculative.

Zanolla et al (1984) studied 60 patients, aged between 37 and 80 years, and divided them into three groups. No difference was found between the groups in terms of sex, age and disease status. MLD was compared with uniform pneumatic pressure and differentiated pneumatic pressure and the circumference of the arm was measured in seven places before and after treatment. MLD produced the best results, and uniform pneumatic pressure also showed a significant improvement over differentiated pressure. The results for the differentiated pressure and control device were not significant. Unfortunately, the groups were not large enough for between-group comparison of effectiveness. What was interesting, however, was that the massage was very effective, although it was applied for only 1 hour three times weekly for 1 month, whereas the mechanical treatments were applied for 6 hours daily over 1 week. Not only has intermittent mechanical pressure been found clinically to worsen the problem in some cases, it was not shown to be particularly effective in this research. These findings suggests that MLD is the treatment of choice for lymphoedema but the use of pressure garments (which mimic the uniform pressure applied in this study) can considerably enhance the treatment. A complex approach of MLD, pressure garments, exercises and skin care is advocated as the treatment approach of choice by lymphoedema specialists (Casley-Smith & Casley-Smith 1994, Foldi 1994) and is recommended in the UK Department of Health guidelines for managing the treatment of post breast cancer lymphoedema (Kirshbaum 1996).

The effectiveness of using a combined approach has been documented by Casley-Smith & Casley-Smith (1992), who described their results of treating 78 patients with oedema following mastectomy with CPT (including the Foldi method of MLD). In the first 4 weeks of treatment, the mean reduction of swelling in grade I lymphoedema was 103% of its initial volume and the mean volume reduction in grade II lymphoedema was 60%, both sets of results being highly significant. A smaller but significant drop in volume was maintained over the following year. When each leg was examined separately, mean losses of fluid were 1.1 L for grade I, 1.3 L for grade II and 3.7 L in elephantiasis. Ko et al (1998) found similarly good results with a reduction in per cent volume and reduced infection rate following CPT in this large study. These positive results have been substantiated by Wozniewski et al (2001) who found that the milder the lymphoedema, the better the results of CPT.

MLD may be more effective than a simplified version often taught to patients for self-massage (simple lymphatic drainage, SLD), as suggested by the results of a small pilot study conducted by Sitzia et al (2001). In addition, aromatherapy with lavender oil can be included in a CPT programme to enhance the comfort, relaxation and self-esteem of women who have had breast cancer (Kirshbaum 1996).

Conclusion

Oedema is present in many of the patients who consult or are referred for physical therapy. It must be controlled immediately it occurs, because chronic oedema can cause fibrosis, adhesions, resultant loss of joint movement and pain. The excess fluid itself causes pain as pressure is exerted on nociceptors; it further prevents cells from being bathed in fresh, newly nourished tissue fluid, thereby reducing normal cellular metabolism. Metabolic circulation may be reduced, together with metabolites, and protein remains in the tissues. Prevention, containment and removal of swelling is the essential hierarchy of care for the tissues, regardless of cause, and massage can be a cornerstone of effective treatment, with skilful application of MLD being essential in the treatment of lymphoedema.

Technique: manual lymphatic drainage

This is the treatment of choice for lymphoedema.

Features

The strokes are extremely light and superficial.

The strokes are directed towards lymph glands along lymphatic channels.

Proximal areas must be cleared before distal areas.

Treatment may need to work across lymphatic watersheds from one area to another.

The trunk often needs clearing before the affected limb.

Progress should be made towards healthy lymph glands.

‘The softer the tissue, the lighter the pressure’ (Wittlinger & Wittlinger 1982).

All techniques should be done as stationary ones or continuous spirals; there is no glide over the skin.

Manipulation: pump technique

Procedure

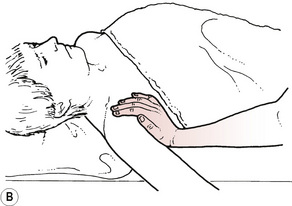

The therapist's hand should be placed flat on the skin, palm down.

The wrist is lifted to pull the hand slightly backwards.

The wrist is then lowered to move the hands forwards, applying a slight forwards pressure (Figs. 11.2A, B).

Hand movements should be controlled so that they follow a slight oval circular pathway.

The skin must move with the hand, which does not glide over the skin.

Manipulation: stationary circles

Procedure

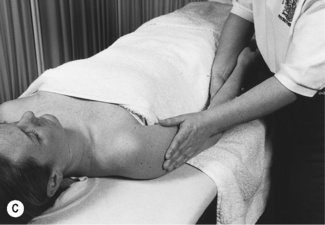

The therapist's fingers should be placed flat on the patient's skin.

The hands should be placed side by side or one on top of the other for reinforcement.

The hands should exert a light pressure in a circling motion (Figs. 11.2C, D).

The skin should move with the hands, which do not glide at all on the skin.

The pressure should go on into the circle and come off out of the circle.

The circles should be applied in the direction of lymph drainage.

Stationary circles should be applied over the lymph nodes and face.

Manipulation: scoop technique

Procedure

The dorsum of the therapist's hand should lie on the patient's skin.

The arm should be rotated so that the carpometacarpal joint of the index finger bears the weight of the hand.

The wrist is then rotated from side to side by slight pronation and supination of the forearm.

The therapist's body position should be appropriate for minimising end-of-range wrist movements.

Manipulation: rotary technique

Procedure

The therapist's hand should lie palm down on the patient's skin.

The fingers and thumb are separated to increase the web space between the thumb and index finger.

As the wrist is lowered, pressure is applied downwards through the heel of the hand.

Pressure is then transferred from the base of the thumb across the heel of the hand to the little finger.

The skin is moved with each rotatory movement.

Each new stroke should begin slightly further along to overlap with the previous one.

Massage in HIV/AIDS

The issues already discussed may apply to individuals who have HIV or AIDS, who may also experience particular problems which warrant further discussion. As with all seriously ill patients, patients with HIV or AIDS may have skin highly sensitive to touch, and the type of massage used must be chosen with care. Slow stroking may appear to be less desirable but may work to desensitise the skin, if the patient is able to tolerate this approach and to persevere with a technique that may initially have been uncomfortable. Some patients have Kaposi's sarcoma, which appears as brown, reddish or purple lesions which can be several inches across. Of course, any open lesions should be avoided and closed lesions massaged lightly.

Hygiene is very important: many people with AIDS suffer from skin rashes and these should be diagnosed accurately before massage. Fungal infections, for example Candida albicans, may be highly contagious. Direct contact with herpes must also be avoided. Hand or foot massage may be appropriate if skin problems are widespread, or sensitive acupressure massage can be given through clothing or bedcovers. Depending on the general medical condition of the patient with AIDS, there may be coughing, vomiting or diarrhoea. No one should be excluded from treatment should they desire it, but massage may have to be interrupted to assist with other needs. When helping with bodily fluids or to change soiled clothing or bedding, gloves should be worn and hands washed thoroughly before recommencing treatment. The therapist should be fully aware of the unit's infection control policy and an appropriate standard of hygiene must be maintained at all times.

The therapist may treat individuals with this diagnosis at an early stage when they may want to boost their immune systems and acquire relaxation and coping skills. Alternatively, she may treat people at the opposite extreme, in the later stages of terminal illness. In the latter situation, the therapist must be prepared to deal with the presenting symptoms, which may be neurological or respiratory, or involve the eyesight. Lang (1993) found, in a retrospective study of community physiotherapy with 10 people with AIDS, that pain was often musculoskeletal in origin.

There is some evidence that massage can decrease stress and increase natural immunity. Ironson et al (1996) studied 29 gay men, of whom 20 were HIV positive, and their responses to daily massage over 1 month. The subjects had a significant increase in natural killer cell number and cytotoxicity, and soluble CD8; a significant decrease was found in anxiety and urinary cortisol levels. The massage was designed specifically to be relaxing; it included elements of Swedish, Trager, polarity, acupressure and craniosacral therapy. Interpretation of the term ‘massage’ was, therefore, very loose and it would be difficult to replicate, either clinically or in a subsequent study. However, the results are supported by later research with adolescents who were HIV positive (Diego et al 2001). Massage twice a week for 12 weeks was compared with a group who received progressive muscle relaxation. It was reported that the immune changes in the massage group included increased natural killer cell number (CD56); in addition, the HIV disease progression markers CD4/CD ratio and CD4 number showed improvement. This study contrasted with that of Birk et al (2000), who found massage did not enhance immune measures. The study by Birk et al was a randomised prospective controlled trial of adults with HIV infection; massage alone was compared with massage in combination with either exercise or stress management-biofeedback treatment and a control group receiving a standard treatment intervention. No significant changes were found in any enumerative immune measure and the conclusion was that massage administered once a week to HIV-infected people does not enhance immune measures. However, all these studies add support to the supposition that massage reduces feelings of stress, anxiety and depression and this can affect natural immunity. There are clear implications, therefore, for the treatment of people with immune-related conditions.

Essential oils may be beneficial for any of these clients, but allergies should be considered as immunity is compromised. As with all clients, but more so with this group, the therapist should ask what the patient's body needs are at each treatment session; a preordained programme may be inappropriate with a fluctuating medical condition and a patient who may feel very ill or be in acute pain. Treatment may be further restricted by drips and drains. Working with this client group can be demanding both professionally and emotionally. It is important to encourage and allow expression of feelings and emotions. It is better for the therapist to attempt to advise and to give clients what they desire in support of their personal strategy, rather than trying to achieve great things. If you work with the client on equal terms, leaving self aside, then you can remain strong, conserving emotional energy for personal, non-professional life, and so work with this client group can be long term rather than transient.

Key points

• Goals of care should not focus on cure or passive receipt of care, but should support and reinforce patient-led strategies.

• Massage may be preferred for short periods of time.

• Be flexible if the condition is fluctuating.

• Abdominal massage may alleviate constipation.

• Massage can reduce oedema, and manual lymphatic drainage is effective in lymphoedema.

• Be prepared to hand over your role to a carer.

• Ensure your intervention enriches, rather than disrupts, relationships.

• Massage can reduce pain and muscle tone, and promote relaxation and well being.

Ahles T.A., Tope D.M., Pinkson B., et al. Massage therapy for patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation. J. Pain Symptom Manage.. 1999;18(3):157-163.

Billhult A., Lindholm C., Gunnarson R., et al. The effect of massage on cellular Immunity, endocrine and psychological factors In woment with breast cancer—a randmosied controlled clinical trial. Auton. Neurosci.. 2008;140(1–2):88-95.

Billhult A., Dahlberg K. A meaningful relief from suffering: experiences of massage in cancer care. Cancer Nurs.. 2001;24(3):180-184.

Birk T.J., McGrady A., MacArthur R.D., et al. The effects of massage therapy alone and in combination with other complementary therapies on immune system measures and quality of life in human immunodeficiency virus. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2000;6(5):405-414.

Bunce I.H., Mirolo B.R., Hennessy J.M., et al. Post-mastectomy lymphoedema treatment and measurement. Med. J. Aust.. 1994;161:125-128.

Casley-Smith J.R., Casley-Smith J.R. Modern treatment of lymphoedema. I. Complex physical therapy: the first 200 Australian limbs. Aust. J. Dermatol.. 1992;33:61-68.

Casley-Smith J.R., Casley-Smith J.R. Information about lymphoedema for patients. Adelaide: Lymphoedema Association of Australia, 1994.

Corbin L. Safety and efficacy of massage therapy for patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2005;12(3):158-164.

Diego M.A., Field T., Hernandez-Reif M., et al. HIV adolescents show improved immune function following massage therapy. Int. J. Neurosci.. 2001;106(1–2):35-45.

Dunn C., Sleep J., Collet D. Sensing and improvement: an experimental study to evaluate use of aromatherapy massage and periods of rest in an intensive care unit. J. Adv. Nurs.. 1995;21(1):34-40.

Eliska O., Eliskova M. Are peripheral lymphatics damaged by high pressure manual massage? Lymphology. 1995;28(1):21-30.

Fellowes D., Barnes K., Wilkinson S. Armoatherapy and massage for symptom relief in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (2):2004. CD002287

Foldi M. Treatment of lymphedema [editorial]. Lymphology. 1994;27:1-5.

Goodall-Copestake B.M. The theory and practice of massage. London: Lewis, 1926.

Grimer R.J., Dalloway J. Tumour recognition - signs and symptoms [letter]. Physiotherapy. 1995;81(7):413.

Hadfield N. The role of aromatherapy massage in reducing anxiety in patients with malignant brain tumours. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs.. 2001;7(6):279-285.

Hollis M. Massage for therapists. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

Hughes D., Lada E., Rooney D., et al. Massage therapy as a supportive care intervention for children with cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2008;35(3):431-442.

Ikomi F., Schmid-Schonbein G.W. Lymph pump mechanics in the rabbit hind leg. Am. J. Physiol.. 1996;271(1–2):H173-H183.

Ironson G., Field T., Scafidi F., et al. Massage therapy is associated with enhancement of the immune system's cytotoxic capacity. Int. J. Neurosci.. 1996;84(1–4):205-217.

Kinmonth J.B. The lymphatics: surgery, lymphography and diseases of the chyle and lymph systems. London: Edward Arnold, 1982.

Kirshbaum M. Using massage in the relief of lymphoedema. Prof. Nurse. 1996;11(4):230-232.

Ko D.S., Lerner R., Klose G., et al. Effective treatment of lymphedema of the extremities. Arch. Surg.. 1998;133(4):452-458.

Kuhnke E. Die physiologischen grundlagen der mannuellen lymphdrainage. Physiotherapie. 1975;66:12.

Kurz I. Textbook of Dr Vodder's manual lymphatic drainage. vol. 2. Heidelberg: Therapy. Haug; 1989.

Kurz I. Textbook of Dr Vodder's manual lymphatic drainage. vol. 3. Heidelberg: Treatment. Haug; 1990.

Kutner J.S., Smith M.C., Corbin L., et al. Massage therapy versus simple touch to Improve pain and mood in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised trial. Ann. Intern. Med.. 2008;149(6):369-379.

Ladd M.P., Kottke F.J., Blanchard R.S. Studies of the effect of massage on the flow of lymph from the foreleg of the dog. Arch. Phys. Med.. 1952;33(10):604-612.

Lang C. Community physiotherapy for people with HIV/AIDS. Physiotherapy. 1993;79(3):163-167.

Leduc A., Caplan I., Lievens P. Traitment physique de l'oedeme du bras. 1981. Paris

Lin M.L., Tsang Y.M., Hwang S.L. Efficacy of a stress management program for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving transcatheter arterial embolization. J. Formos. Med. Assoc.. 1998;97(2):113-117.

McCaffery M., Wolf M. Pain relief using cutaneous modalities positioning and movement. Hosp. J.. 1992;8(1–2):121-153.

McNamara P. Massage for people with cancer. London: Wandsworth Cancer Support Centre, 1994.

Mortimer P.S., Simmonds R., Rezvani M., et al. The measurement of skin lymph flow by isotope clearance—reliability, reproducibility, injection dynamics and the effect of massage. J. Invest. Dermatol.. 1990;95(6):677-682.

Richards K.C. Effect of a back massage and relaxation intervention on sleep in critically ill patients. Am. J. Crit. Care. 1998;7(4):288-299.

Sitzia J., Sobrido L., Harlow W. Manual lymphatic drainage compared with simple lymphatic drainage in the treatment of post-mastectomy lymphoedema. Physiotherapy. 2001;88(2):99-107.

Stephenson N.L., Weinrich S.P., Tavakoli A.S. The effects of foot reflexology on anxiety and pain in patients with breast and lung cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2000;27(1):67-72.

Tappan F.M. Healing massage techniques. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange, 1988.

Thibodeau G.A., Patton K.T. Anatomy and physiology, sixth ed. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2007.

Tidy N.M. Massage and remedial exercises. London: John Wright, 1932.

Tyler D.O., Winslow E.H., Clark A.P., et al. Effects of a one minute back rub on mixed venous saturation and heart rate in critically ill patients. Heart Lung. 1990;19(5):562-565.

Vodder E. Le drainage lymphatique: une nouvelle methode therapeutique santé pour tous. Wittlinger H., Wittlinger G., editors. Textbook of Dr Vodder's manual lymphatic drainage, vol. 1. Heidelberg: Haut, 1936.

Wakim K.G., Martin G.M., Terrier J.C., et al. Effects of massage on the circulation in normal and paralyzed extremities. Arch. Phys. Med.. 1949;30:135-144.

Wilkie D.J., Kampbell J., Cutshall S., et al. Effects of massage on pain intensity analgesics and quality of life in patients with cancer pain: a pilot study of a randomized clinical trial conducted within a hospice care delivery. Hosp. J.. 2000;15(3):31-53.

Wilkinson S., Aldridge J., Salmon I., et al. An evaluation of aromatherapy massage in palliative care. Palliat. Med.. 1999;13(5):409-417.

Wilkinson S.M., Love S.B., Westcombe A.M., et al. Effectiveness of aromatherapy massage In the management of anxiety and depression In patients with cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2007;25(5):532-539.

Wilkinson S., Barnes K., Storey L. Massage for symptom relief in patients with cancer: systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs.. 2008;63(5):430-439.

Wittlinger H., Wittlinger G. third ed. Textbook of Dr Vodder's manual lymphatic drainage. vol. 1. Heidelberg: Haut Verlag; 1982. Basic course

Wozniewski M., Jasinski R., Pilch U., et al. Complex physical therapy for lymphoedema of the limbs. Physiotherapy. 2001;87(5):252-256.

Zanolla R., Monzeglio C., Balzarini A., et al. Evaluation of the results of three different methods of postmastectomy lymphedema treatment. J. Surg. Oncol.. 1984;26:210-213.