6 The abdomen

At the end of this chapter you should be able to

1. Find, recognize and name the constituent bony components of the boundaries of the abdomen, including the lower ribs, cartilages, xiphoid process, lumbar vertebrae and pelvic girdle.

2. Palpate many of the bony features, being able to relate one to another.

3. Locate, name or number the spines and transverse processes of all the lumbar vertebrae.

4. Recognize and palpate the main bony landmarks of the pelvis, sacrum and coccyx.

5. Name all the joints of the lumbar spine and pelvis, noting their active and passive range of movement.

6. Give the class and type of all the joints named.

7. Palpate the joint lines, where possible, and give their surface markings.

8. Demonstrate any accessory movements which may be possible in the joints of the lumbar spine and pelvis.

9. Locate and name the muscles which surround the abdomen.

10. Draw the shape of the muscle on the surface and give its attachments.

11. Demonstrate the actions of all of the muscles covering the abdomen.

12. Give an account of their actions and functional significance.

13. Describe the main anatomical regions of the abdomen.

14. Give the surface markings of the liver, spleen, pancreas, gall bladder, small intestine, large bowel, kidneys and bladder.

15. Demonstrate the cutaneous distribution of the nerves covering the abdomen, giving an outline of the course each takes.

16. Describe the arrangement of the main arteries in the abdomen, giving their surface markings.

17. Describe the arrangement of the main veins in the abdomen, giving their surface markings.

Bones

The abdomen consists mainly of soft tissue contained with predominantly muscular walls. Its only bony features are:

• above: the xiphoid process at its centre in the front, the lower border of the seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth costal cartilages, the tip of the eleventh rib and the inferior border of the twelfth rib

• posteriorly: the body of the twelfth thoracic vertebra completes the ring

• below: the pelvic inlet comprises the pubis anteriorly, its superior rami on either side, the anterior border and the crest of the ilium and posteriorly the base of the sacrum

It is, however, important to mark out these boundaries as they provide useful landmarks for some of the organs the abdomen contains.

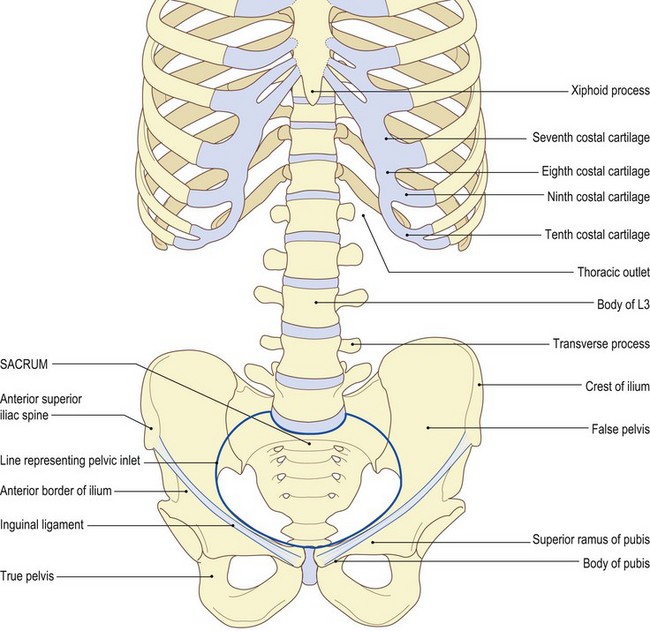

The thoracic outlet (Fig. 6.1a, b)

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model is in the supine lying position.

• The thoracic outlet. Find the xiphoid process, which is the most inferior portion of the sternum. Trace along the costal margin beyond the costal angle (the ninth costal cartilage) to its lowest extremity, which is normally the tenth rib. Continuing posteriorly, the eleventh rib becomes evident, with its tip just anterior to the mid-axillary line, with the tip of the twelfth rib slightly lower and just posterior. The tip of the twelfth rib normally lies on the same level as the spine of the first lumbar vertebra.

The pelvic girdle

Palpation

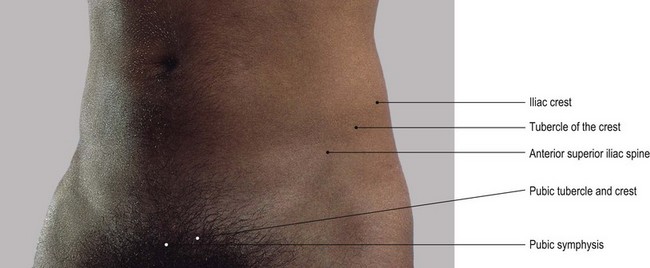

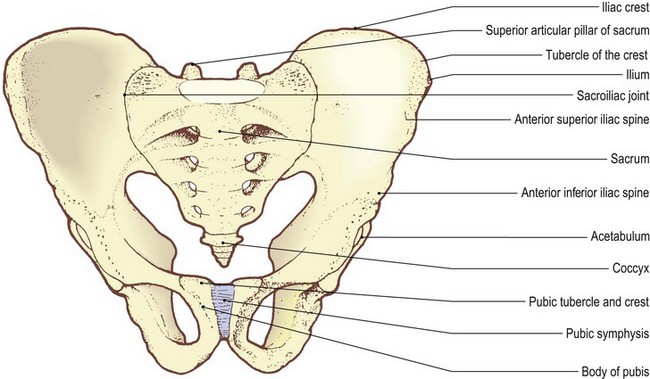

• The pelvic girdle. Identify the anterior superior iliac spine at the anterior extremity of the iliac crest. Trace the lateral lip of the iliac crest posteriorly, beyond the iliac tubercle to the posterior superior iliac spine and sacrum. Now, run the pads of your fingers down the central part of the abdominal wall to about 5 cm above the genitalia. The pubic tubercles become evident on either side, with each pubic crest running medially to a central space which marks the pubic symphysis. The bony ring is completed by the superior ramus of the pubis, which is difficult to palpate, and anterior border of the ilium, easily identifiable in its upper section. The inguinal ligament stretches above this region from the pubic tubercle to the anterior superior iliac spine.

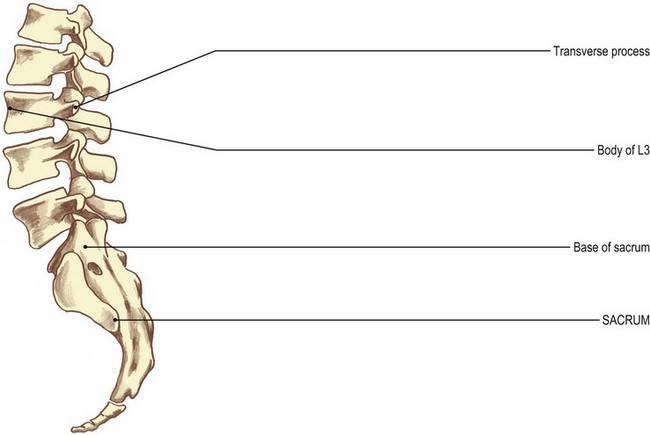

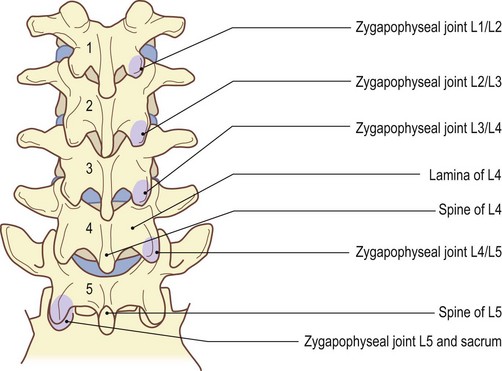

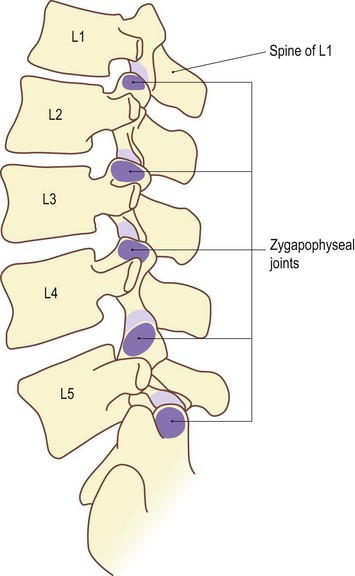

The lumbar vertebrae

There are five lumbar vertebrae, L1 being the smallest and L5 the largest. As in all other vertebrae, their bodies are anterior and their spines are posterior. Laterally, they present transverse processes, the fifth being much larger than the rest. Their upper articular processes face inwards and their lower facets face outwards, those of the fifth facing more anteriorly. There is a large neural canal in the lumbar region which is more triangular in shape.

Palpation

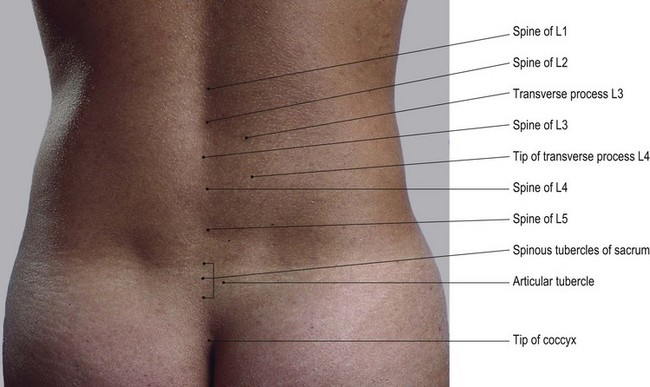

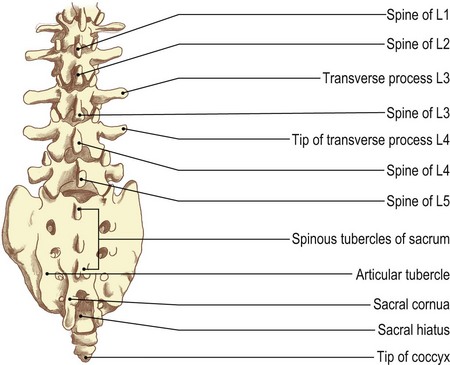

Posteriorly, the spines of the lumbar vertebrae project backwards and are individually identifiable.

For palpation in this region, the model is in the prone lying position.

• The lumbar vertebrae. Place a firm pillow under the abdomen which flattens the lumbar lordosis. This makes the spines of the lumbar vertebrae become more pronounced, appearing as a line of flattened edges forming a crest down the centre of the lumbar region (Fig. 6.1c, d). The spines are continuous with those of the sacrum below and the thoracic vertebrae above.

• The spines of the lumbar vertebrae. Immediately above the central part of the sacrum is a hollow, due to the spine of the fifth vertebra being shorter and the body being situated slightly more anterior than the rest. The small gaps between the spines tend to disappear when the vertebral column is flexed, owing to the tension of the supraspinous ligament.

• The transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. Apply deep pressure approximately 5 cm lateral to the vertebral spines beyond the bulk of the erector spinae muscles. Palpate the tips of the transverse processes.

• Note 1. The transverse process of the first lumbar vertebra is particularly easy to identify.

• Note 2. The transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae are relatively thin compared with those of the thorax and may be tender to palpate.

The sacrum

The sacrum comprises five fused vertebrae, S1 being the largest and S5 being the smallest. The sacrum is triangular in shape with its base uppermost. Evidence of the separate vertebral bodies is still clear on the anterior surface. A line of spinous tubercles runs vertically down the centre of its posterior surface and it is marked on either side by articular tubercles. Laterally the sacrum presents large lateral masses beyond its neural foramina. The sacrum is tilted forwards above, with its lower section projecting backwards.

Palpation

• The sacrum. Identify the posterior surface of the sacrum between the posterior borders of the two ilia. Its lower section projects backwards and is easy to palpate. Its upper section (the base) lies more anterior and is more difficult to examine. Identify its central, vertical series of spinous tubercles which are in line with the lumbar spines and the coccyx. These are accompanied on either side by a row of articular tubercles which are all palpable (Fig. 6.1c, d).

The coccyx

The coccyx comprises three or four rudimentary vertebrae normally fused into one bone, the uppermost being the largest and the lowest being a very small tubercle of bone. Normally it is tilted, with its inferior tip pointing downwards and forwards.

Palpation

• Note. As the coccyx varies considerably in size and shape it may prove a little difficult to palpate. Several alternative methods can be employed:

• Note. In many subjects the coccyx is angled forwards and the finger must be pressed deep into the cleft to identify the shape. Care must be taken as pressure on the bone can cause pain, particularly if the joints between it and the sacrum have been damaged at any time.

Joints

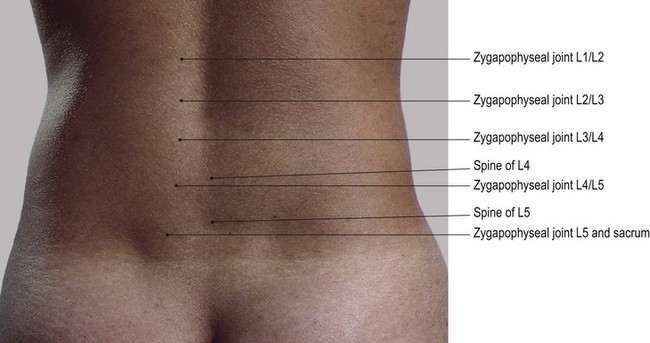

The lumbar spine (Fig. 6.2)

Palpation

The zygapophyseal joints are the most superficial in the lumbar region. They are nevertheless covered by thick, strong muscle, making the task of palpation extremely difficult.

For palpation in this region, the model is in the prone lying position.

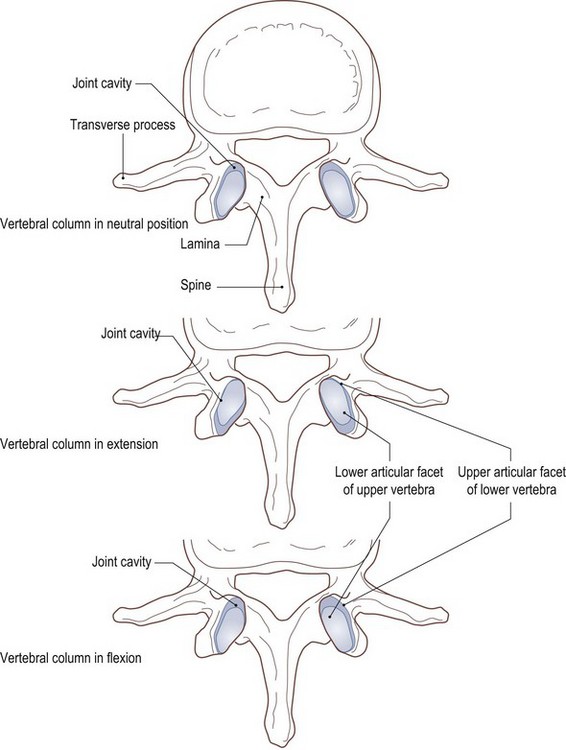

• The zygapophyseal joints. Press your fingers between the sides of the vertebral spines and the parallel-running column of muscle (sacrospinalis). Identify the sides of each of the spines. In some subjects, it may also be possible to palpate the laminae of the vertebra. Each is a little higher than its corresponding spine, being almost totally hidden by the thick muscle layer.

• Posterior-anterior pressure. Using the tips of your thumbs, apply deep pressure through the muscle. This exerts pressure on the posterior aspect of the zygapophyseal joints, which lie 1 cm lateral and slightly lower than the vertebral spine. With great care and precision, this pressure can be targeted on to the upper articular pillar of the vertebra below by moving lateral to the joint, or on to the lower articular pillar of the vertebra above by moving just medial to the joint.

• Note. The lower facets of the vertebrae are convex anteriorly and fit snugly into the concave anterior edge of the upper facets of the vertebra below. Thus, anterior pressure on the lower vertebra causes its articular facet to glide forwards, slightly parting its anterior segments, whereas pressure on the upper vertebra pushes the lower facet into the socket, preventing any further movement (Fig. 6.2d, e).

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Distraction. Distraction (traction) of the joints of the lumbar spine is the only true accessory movement possible. All other movements of gliding, gapping and compression of the zygapophyseal joints, together with twisting and compression of the intervertebral discs, occur in the area during normal lumbar activities.

• Note 1. Traction can be applied to this area in many ways, either manually or mechanically. The lumbar column, however, can be placed in many different positions to achieve the therapeutic result required.

• Note 2. Extension of the lumbar spine tends to create a ‘close-packed’ position for the individual joints as the articular surfaces come into full contact and ligaments become taut. This, therefore, is not a desirable position in which to achieve traction. All other positions towards flexion allow space for the joint surfaces to part or glide. In full flexion, however, the ligaments again become taut, preventing the required movements. Traction in full flexion is almost impossible to apply.

• Note 3. The optimum position in which to apply traction is midway between extension and flexion.

• Note 4. Simple traction can be applied to the lumbar spine by applying a distraction force to either the pelvis or the lower limbs, with the subject lying either supine or prone. It is preferable to place a pillow under the abdomen in the latter position to prevent extension.

• Note 5. Manual traction can also be applied with the model sitting or standing. This is achieved by raising the upper trunk and allowing the pelvis and lower limbs to act as the traction force.

• Note 6. Mechanical traction can be applied in many positions of the lumbar spine, avoiding full extension and full flexion for the same reasons as outlined above. It may be applied continuously or intermittently over a set period of time. These therapeutic techniques are complex and need skill and knowledge of procedures and precautions. For further study, reference should be made to literature dedicated to this subject.

The pelvis (Figs 6.3 and 6.4)

Posteriorly, the sacrum articulates on either side with the ilium (innominate) bone at the sacroiliac joints (also discussed in Chapter 3). Anteriorly, the two pubic bodies articulate with each other at the pubic symphysis. The former is a very stable plane synovial joint supported by powerful interosseous and accessory ligaments. The latter is also stable, but is a secondary cartilaginous joint containing a modified disc of fibrocartilage. The sacroiliac joints allow a small degree of rotation of the sacrum, with respect to the innominate bones, about an axis through its interosseous ligament. Movement is more noticeable in young females, particularly during pregnancy and childbirth, reducing considerably after the third decade. In males, movement is negligible and virtually nil after the second decade.

The pubic symphysis allows a slight rocking and twisting movement which accompanies any movements occurring at the sacroiliac joints.

The sacroiliac joint

Palpation

surface marking

For palpation in this region, the model is in the prone lying position.

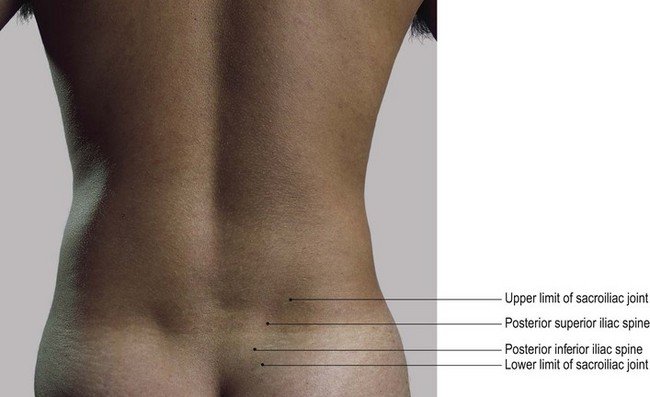

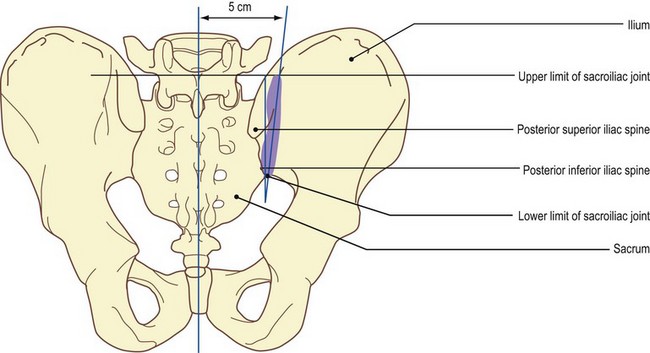

• The sacroiliac joint. Place a pillow under the abdomen. Now identify the posterior superior iliac spine. The sacroiliac joint can be identified, lying 1 cm lateral and 1 cm anterior to this spine. It lies on an oblique line which extends above and below for a further 2 cm. The joint can also be marked by an oblique line passing downwards and medially from a point 5 cm lateral to the spine of the fifth lumbar vertebra to a point just lateral to the posterior inferior iliac spine (Fig. 6.3b). It is impossible to palpate this joint.

Accessory movements

Palpation

Little movement occurs at the sacroiliac joint. There is more movement in young females and less in middle-aged and elderly males (see above).

• Rocking. Rocking the sacrum around a frontal axis can be achieved. Place the heel of one hand over the apex and the heel of your other hand over the base of the sacrum. Now apply alternate pressure to the apex and base. This produces a slight rocking movement of the sacrum between the two innominate bones.

• Localization of movement. This movement can be increased locally on one side. Place one hand on the apex of the sacrum and the other on the posterior aspect of the crest of the ilium. The opposite movement can be produced if you place one hand on the base of the sacrum and the other on the ischial tuberosity.

• Note. The pressure applied to these two areas must be downwards and towards each other, in the same direction as the movement of each component. It is a difficult movement to obtain and some skill and practice are necessary before it can be achieved.

• Gapping. The model is in the supine lying position. In this position, the posterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint can normally be gapped or at least stressed by using the leverage of the femur. Flex the model’s opposite knee and hip and roll the limb and pelvis towards you. When the pelvis is rotated approximately 45°, apply a downward and medial pressure towards the opposite hip joint to the femoral condyles.

• Note. This technique is used in the examination and treatment of sacroiliac problems and is covered in greater detail in the manipulation literature.

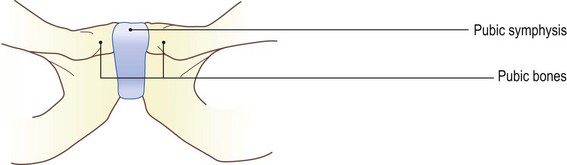

The pubic symphysis

This joint is situated centrally at the lower aspect of the abdomen between the two pubic bones and just above the external genitalia.

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model is in the supine lying position.

• The pubic symphysis. Locate the pubic tubercles on the upper border of the body of the pubis on either side of the midline. Note that there is a depressed line between the two tubercles. Trace this line downwards for about 2.5 cm. This indicates the anterior marking of the pubic symphysis, being the medial surfaces of the pubic bones separated only by the intervening interarticular disc.

Accessory movements

Palpation

The slight twisting and gapping that occurs at this joint is due to stresses on the pelvis and sacrum which occur during movements at the sacroiliac and hip joint.

• Twisting and gapping. Apply pressure to the anterior surface of the pubic body on one side only. This will produce a slight gliding movement.

• Compression and stressing. The model is in the side lying position. Apply a downward compression force to the upper part of the ilium. This increases compression at the pubic symphysis while also stressing the posterior sacroiliac ligament.

• Lateral stressing. The model is in the supine lying position. The two ilia can be stressed laterally if you apply a downward and lateral pressure to the two iliac crests. This produces a distraction force to the pubic symphysis. In addition, it produces an anterior gapping and stress on the anterior ligament of the sacroiliac joint.

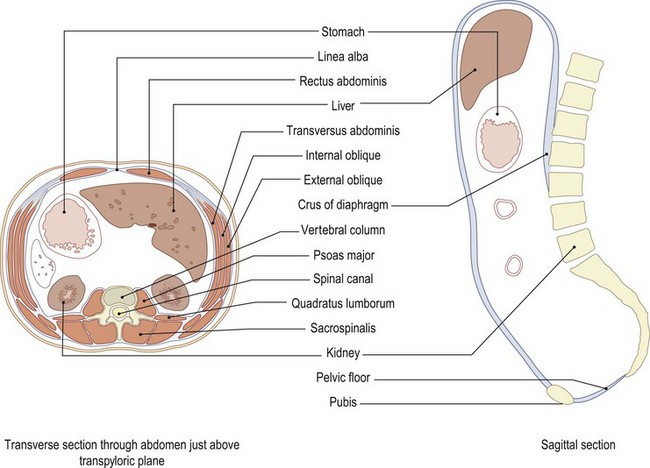

Muscles

The abdominal muscles form a continuous wall around the abdominal viscera. The cavity so formed is enclosed:

• posteroinferiorly: the vertebral column and psoas major

• posterolaterally: quadratus lumborum

• anterolaterally: the internal and external oblique abdominal muscles

• anteriorly: the above muscles supported on their deep surface by transversus abdominis

• anteriorly: rectus abdominis

• inferiorly: the muscles which form the pelvic floor (i.e. levator ani and coccygeus).

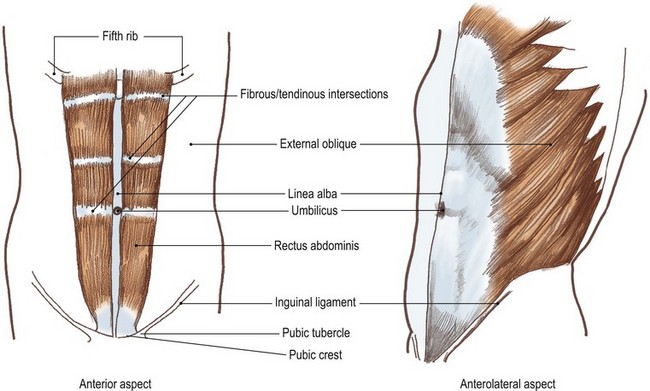

Some of these muscles may be palpable when they are contracting, although they may not always appear distinct (Fig. 6.5).

Identification of structures and muscles in this area is dependent, to a certain extent, on the physique of the subject. Subcutaneous fat in the superficial fascia covering the abdomen can hinder accurate identification.

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model is in the supine lying position.

• Rectus abdominus. Place both your hands on the central area of the abdomen, one above and one below the umbilicus. Now ask the model to raise the head. Palpate the column of muscle running down either side of the central depressed line (the linea alba) (Fig. 6.5a–d). These two columns of muscle are the left and right sections of the rectus abdominus muscle.

• Note 1. Each muscle is narrow inferiorly. It can be traced from the pubic tubercle and crest below to its broader superior attachment to the fifth, sixth and seventh ribs.

• Note 2. The upper attachment of rectus abdominus is V-shaped, as the attachment to the fifth rib laterally is higher than that to the seventh costal cartilage centrally. The lateral border of each muscle is convex. The muscle is interrupted by three transverse depressed fibrous intersections. These are at the level of the xiphoid, the umbilicus and midway between the two. These appear as transverse grooves across the muscles.

• The internal and external oblique muscles. Ask the model to flex the trunk. Palpate the contraction of both these muscles.

• Note. Each of these muscles can be identified more easily if its action is resisted.

• The right external oblique muscle. Stand on the model’s left-hand side. Ask the model to rotate the trunk to the left against resistance. This will be easier if you apply resistance to the right shoulder, preventing the head and shoulder from being lifted and turned to the left. Palpate the contraction of the muscle. Contraction of the muscle tightens the aponeurosis just above its attachment to the right iliac crest.

• The left internal oblique. This muscle lies deep to the external oblique so that, if you repeat the technique described above (rotation of the trunk to the left) the left internal oblique also contracts. The contraction can be palpated between the left iliac crest and the umbilicus.

• Quadratus lumborum. The model is in the prone lying position. Ask the model to raise the head and shoulders. The muscle can be palpated on either side of the vertebral column, between the twelfth rib above and the posterior part of the iliac crest below. It mostly lies deep to latissimus dorsi, but its anterior border can be palpated just posterior to the mid-axillary line.

In this region sacrospinalis (erector spinae) lies close to the spinous processes of the lumbar vertebrae. These muscles form two firm columns passing from the posterior part of the iliac crest and sacrum below, to the angle of the ribs and transverse processes of the thoracic vertebrae.

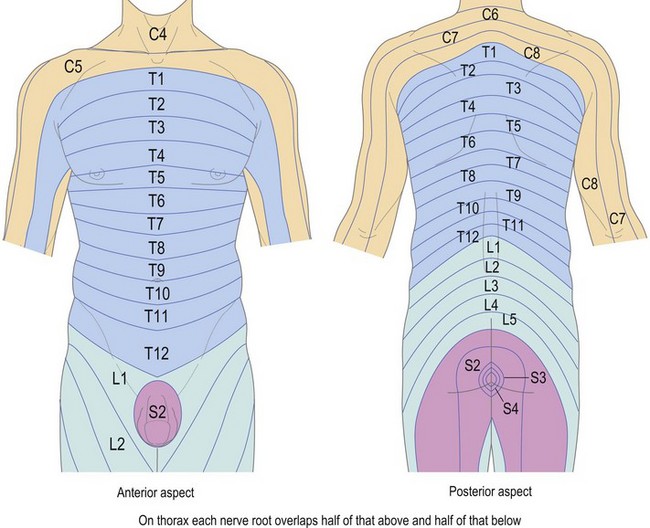

Nerves (Fig. 6.6 a, b)

The nerve supply to the abdomen and lower limbs is derived from the T8–12, all five lumbar, all five sacral and the coccygeal nerve roots. The arrangement of these nerves is extremely complex (see Palastanga et al 2002) and is dealt with here in outline only.

The thoracic nerves

Nerve roots T8–11 behave in a similar manner to intercostal nerves, supplying muscles in intercostal spaces and anteriorly contributing to the supply to the abdominal muscles. Their cutaneous branches follow the same general direction, supplying a band of skin running downwards and forwards.

The lumbar plexus

This is formed by part of T12 and L1–4. It supplies muscles of the lower abdomen, pelvis and front and inner side of the thigh. Its cutaneous supply is to the lower back and running downwards and forwards to the lower abdomen and the front and inner side of thigh and the inner side of the leg and foot.

The sacral plexus

Deriving its fibres from the ventral rami of L4, L5 S1, S2, S3 and S4 the sacral plexus supplies the muscles of the gluteal region, hamstrings, leg and foot. Its cutaneous supply is the gluteal region, back of the thigh, anterior, lateral and posterior aspects of the leg and plantar and dorsal aspects of the foot.

The coccygeal plexus supplies an area of skin around the anus.

The larger nerves of this region are situated deeply within the abdomen. Those of the lumbar plexus are formed within psoas major, while those of the sacral plexus mainly lie in front of the sacrum. All nerves that reach the surface of the abdominal and lumbar areas are too small to palpate. Nevertheless, these cutaneous nerves often influence their areas of distribution, with palpable signs such as changes in temperature and sweating. It is therefore important to study the cutaneous distribution over the abdomen and lumbar areas. As in the costal area, there is an overlap of root supply, each nerve covering an area of skin above and below.

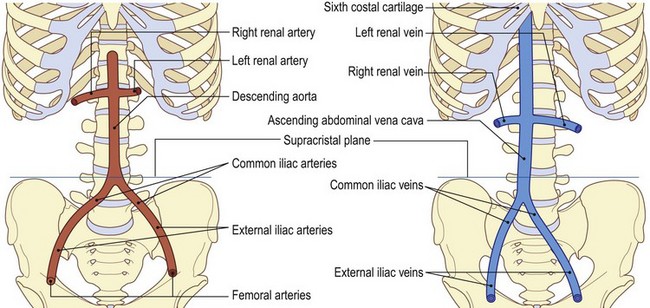

Arteries (Fig. 6.6c)

All the larger arteries of the abdomen are also situated deeply within the abdominal cavity and are difficult or impossible to find.

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model is in the supine lying position.

• The pulsations of the abdominal aorta. Using your fingers, apply deep pressure to the left of the umbilicus. This compresses the abdominal aorta against the lumbar vertebral bodies.

• Note. This technique is unpleasant. It can be improved by encouraging the model to relax the abdominal muscles.

• The surface marking of the abdominal aorta. Draw a line vertically from a point on the midline 2.5 cm above the transpyloric plane (see Fig. 6.7b) to a point just to the left of the midline 2.5 cm below the supracristal plane (Fig. 6.6c).

• The common iliac arteries. At this point, the aorta divides into the common iliac arteries. These diverge from each other at an angle of approximately 37° to bifurcate again one vertebra below (lower border of the fifth lumbar vertebra) into the internal and external iliac arteries.

• The external iliac artery. This artery can be marked as it passes to the mid point of the inguinal ligament to be continued below the ligament as the femoral artery.

Veins (Fig. 6.6d)

Again, all the large veins of the abdomen are deep within the cavity and impossible to palpate. It is, however, quite important to know where the abdominal portion of the inferior vena cava commences and leaves the abdominal cavity.

Palpation

surface marking

For palpation in this region, the model is in the supine lying position.

• The abdominal portion of the inferior vena cava. This vein commences at the junction of the two common iliac veins at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. It progresses upwards and slightly to the right. It is initially accompanied on its left by the abdominal aorta. It leaves the abdominal cavity by passing behind the liver and through the diaphragm at the level of the spine of T8 (Fig. 6.6d).

• The inferior vena cava. Draw a line 2.5 cm wide, commencing at a point just to the right of the midline 2.5 cm below the supracristal plane (lower body of the fourth lumbar vertebra), to a point just above the sixth costal cartilage on the right, where it passes through the vena caval opening in the tendinous portion of the diaphragm (Fig. 6.6d).

Structures within the abdominal cavity

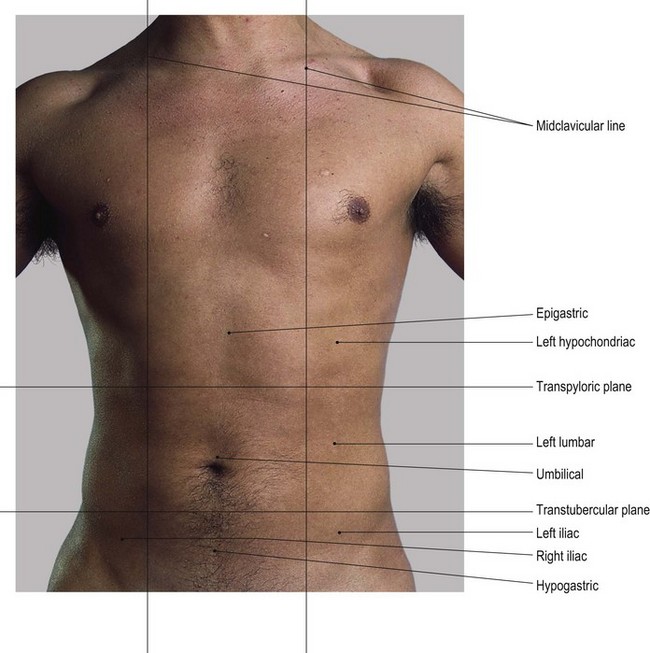

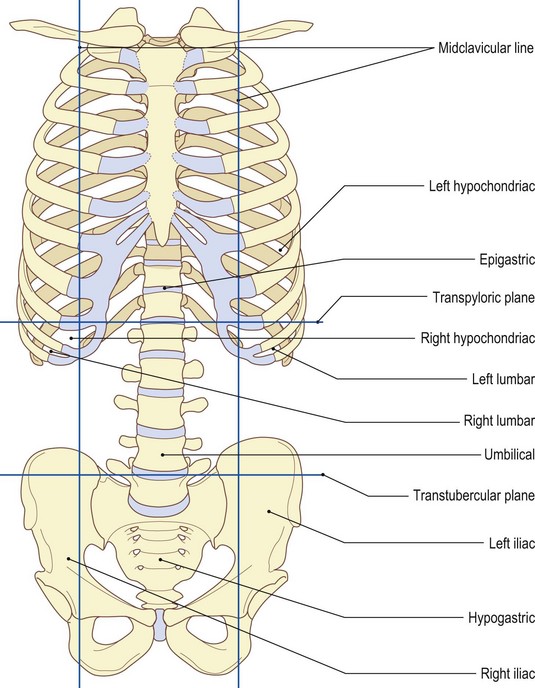

For convenient location of viscera, the abdomen may be divided into nine regions by two vertical and two horizontal lines (Fig. 6.7a, b). Other methods of dividing the abdomen into regions also exist but will not be covered here (Keogh and Ebbs 1984).

Palpation

surface marking

For surface markings in this region, the model is in the supine lying position.

• The mid-clavicular lines. Trace the two vertical lines as follows. They pass superiorly from the mid-inguinal point, which is halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle, to the mid point of the clavicle. They are usually referred to as the mid-clavicular lines.

• The upper horizontal line and the transpyloric plane. This is drawn level with the tip of the ninth costal cartilage. It crosses the tip of the twelfth rib and the spine of the first lumbar vertebra. This is known as the transpyloric plane as it also passes through the pylorus of the stomach.

• The lower horizontal line and the transtubercular plane. This is drawn across the abdomen between the tubercle of the crest of each ilium and is known as the transtubercular plane (Fig. 6.7a, b). It crosses the vertebral column level with the upper portion of the body of L5. It may serve as a useful landmark when identification of lumbar vertebrae is necessary.

The three regions above the transpyloric plane are the right and left hypochondriac, with the epigastric centrally. The three regions between the transpyloric and transtubercular planes are the right and left lumbar, with the umbilical centrally. The three lower regions are the right and left iliac, with the hypogastric centrally.

Organs in the abdominal cavity are normally quite movable, some changing their shape and size according to their contents. This makes surface marking difficult and often unreliable. It is, however, important to be able to mark the areas in which the particular organ lies and note any fixed sites where markings are constant.

General locations and overview

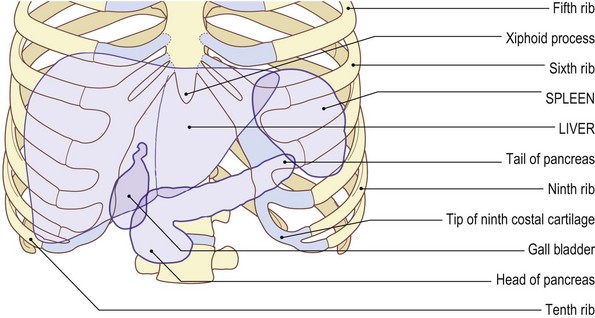

• The liver. This organ lies mainly in the right hypochondriac and epigastric areas.

• The spleen. This organ is located mainly in the left hypochondriac and extends posteriorly into the epigastric area.

• The pancreas. This organ lies on the transpyloric plane between the epigastric and umbilical areas.

• The gall bladder. This organ lies on the transpyloric plane where it crosses the right mid-clavicular line.

• The stomach. The stomach varies considerably in size but is normally in the left hypochondriac and umbilical areas.

• The duodenum. This organ lies partly in the umbilical and partly in the epigastric areas, the transpyloric plane passing through its second part.

• The small intestine. This organ lies mainly in the hypogastric area.

• The caecum and appendix. These organs lie in the right iliac region.

• The large intestine. This organ passes through the right iliac and lumbar, umbilical, left lumbar and iliac areas and passes down through the hypogastric area.

• The kidneys. These organs lie partly in the epigastric and partly in the umbilical areas.

• The bladder. This organ lies behind the two pubic bones and pubic symphysis.

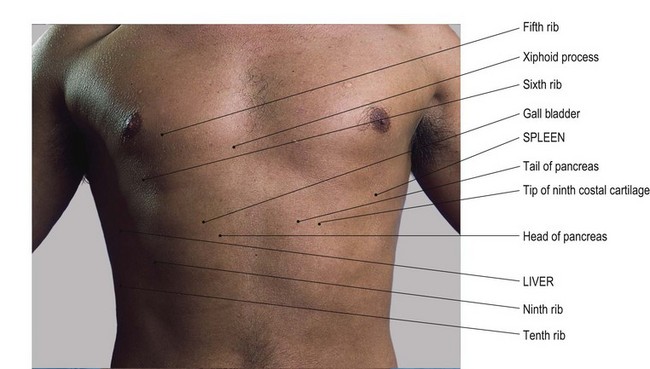

The liver (Fig. 6.7c, d)

The liver is a large wedge-shaped organ situated mainly in the right hypochondriac and epigastric regions of the abdomen just below the diaphragm. Its upper surface is moulded by the undersurface of the diaphragm. The right side is thicker, narrowing as it passes towards the left. Posteriorly, it is grooved by the inferior vena cava.

Palpation

surface marking

• Note. For identification of the following organs, the model is either in the supine or prone lying position.

• The liver. The model is in the supine lying position. The position of the liver is fairly constant in healthy subjects. Mark its upper boundary by drawing a line horizontally at the level of the xiphisternal joint, extending some 7 cm to the left of the midline and all the way round the right side of the thoracic cage. Mark its lower border by drawing an oblique line beginning 7 cm to the left of the midline, crossing the left costal margin at the eighth costal cartilage, reaching the right costal margin at the ninth costal cartilage and continuing around the costal margin.

The spleen (Fig. 6.7c, d)

The spleen [splen (L) = spleen] is a reservoir for blood. It is soft and highly vascular and is just deep to the lower left ribs below the diaphragm and behind the stomach. In addition to the storage of blood, it is part of the reticuloendothelial system. It contains phagocytes which engulf microorganisms, foreign particles and damaged cells. It is involved with the manufacture of white blood cells and in the infant it will also produce red blood cells.

The spleen lies under cover of the ribs, although it is an abdominal organ. This is due to the domes of the diaphragm rising into the thorax from its costal attachments.

Palpation

surface marking

• The spleen. The model is in the supine lying position. The spleen lies posteriorly on the left side of the body. It is situated deep to the ninth, tenth and eleventh ribs and extends as far forwards as the mid-axillary line. It is approximately 10 cm long, 7 cm deep and 3–4 cm thick. Although it occasionally projects just below the costal margin, the spleen cannot usually be palpated unless it is enlarged to approximately three times its normal size.

• Note 1. The spleen is often ruptured in severe accidents where the chest is crushed and may well be overlooked. This will lead to large amounts of blood escaping into the abdominal cavity.

• Note 2. The spleen can be removed without affecting the human body too seriously.

The pancreas (Fig. 6.7c, d)

The pancreas [pan (Gk) = all, keras (Gk) = flesh] is a strangely shaped gland resembling a large tadpole, having a head to the right with a body and tail which narrows as it passes to the left.

Palpation

surface marking

• The pancreas. The model is in the prone lying position. The organ is approximately 10 cm long and 4 cm broad at its head. It is situated anterior to the vertebral column, level with the body of the first lumbar vertebra. The head is surrounded by the four sections of the duodenum, the pylorus of the stomach lying anterior to the body. The pancreatic duct passes from the head to the right, emptying into the second part of the duodenum at a point on the transpyloric plane 2 cm to the right of the median line (Fig. 6.7c, d). Behind the body lie the superior mesenteric and splenic veins; just below, they form the portal vein. The head is related posteriorly with the inferior vena cava and the right crus of the diaphragm. The body lies just in front of the abdominal aorta. The tail is related to the spleen at its far left and with the stomach anteriorly. The pancreas is not palpable in the normal subject.

The gall bladder (Fig. 6.7c, d)

The gall bladder is a small reservoir, approximately 3 cm in diameter, with a short tail passing posteriorly.

Palpation

surface marking

• The gall bladder. The model is in the supine lying position. The organ is situated below the centre of the anterior border of the liver, projecting a little below the right costal margin deep to the costal angle level with the ninth costal cartilage (Fig. 6.7c, d). In the normal subject, the gall bladder is difficult to palpate. It discharges bile through the bile duct into the second part of the duodenum, which aids in the breakdown of fatty foods during digestion.

• Note. Sometimes stones are formed in the gall bladder and are passed down the tortuous and sometimes narrowing tubes of the cystic and bile ducts. The blockage of these tubes causes acute pain and often irritates other structures in this area. If this is a recurring problem, the gall bladder can be removed (cholecystectomy).

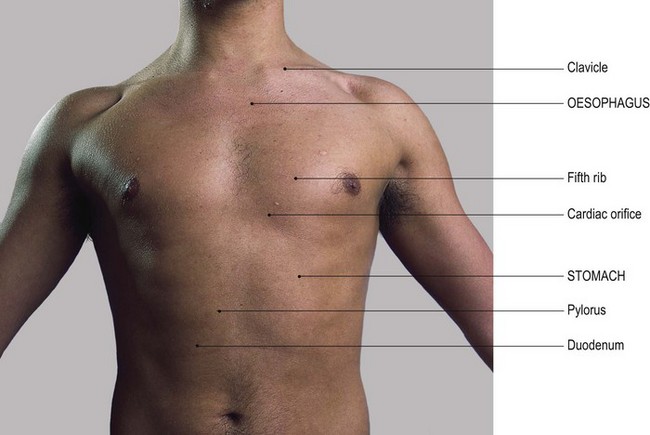

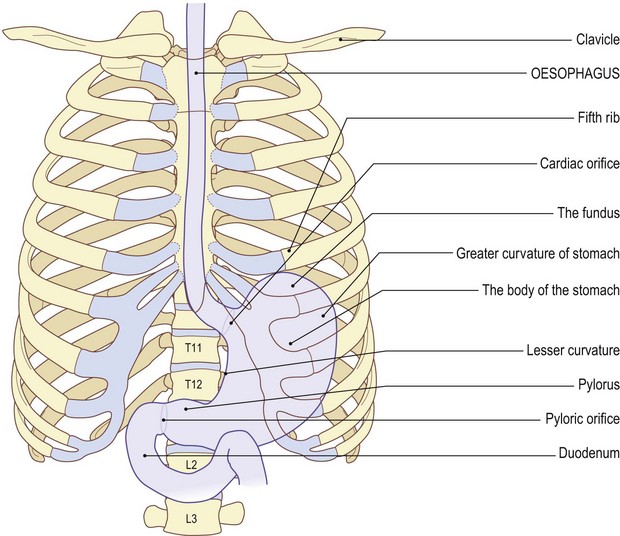

The stomach (Fig. 6.8)

The stomach [stomachos (Gk) = the Greeks used this word for the gullet and the oesophagus; later, they used ‘gaster’ to denote its lower end]. This is a mobile, muscular, highly vascular organ. Its function is as a container in the digestive system. It is situated deep to the lower left rib cage, below the diaphragm, to the left of the liver and in front of the spleen. It receives food from the oesophagus [oiso (Gk) = I carry, phagein (Gk) = food] through its cardiac orifice into its upper part (the fundus). After passing through the body of the stomach, the partially digested food is passed on through the pylorus and pyloric orifice into the first part of the duodenum. The stomach varies enormously in shape and size according to its contents. It is basically J-shaped, its upper section being thicker and more expanded. Its lower end becomes narrower as it passes medially and slightly upwards, continuing as the first part of the duodenum.

Palpation

surface marking

• The stomach. The model is in the supine lying position. Although the central section of the stomach varies in shape and size, its two openings – the cardiac and pyloric orifices – remain comparatively fixed.

• The cardiac orifice. Mark this orifice by drawing a short oblique line, approximately 2 cm long, along the seventh costal cartilage, 2.5 cm to the left of the midline, where it is level with the tip of the xiphoid process.

• The pyloric orifice. This orifice can be identified lying on the transpyloric plane, 1.5 cm to the right of the midline.

• The fundus. The fundus, or upper part of the stomach, may rise up as far as the fifth intercostal space, 7 cm left of the midline, or as far down as the tenth costal cartilage.

• The lesser curvature of the stomach. Mark this area by drawing a curved line, concave to the right, joining the cardiac and pyloric openings.

• The greater curvature of the stomach. Mark this area by drawing a line, convex to the left, joining the upper limit of the stomach at the fifth intercostal space to approximately the tenth costal cartilage (Fig. 6.8a, b).

The duodenum (Fig. 6.8)

The duodenum [duoden arius (L) = continuing twelve. Herophilus in 344 bc measured the duodenum as twelve finger breadths] is the continuation of the digestive tract beyond the pylorus of the stomach.

Palpation

surface marking

• The duodenum. The model is in the supine lying position. The duodenum is approximately 25 cm long.

• First part. Initially, the duodenum passes upwards, backwards and to the right for 5 cm as far as the costal margin.

• Second part. This passes downwards to the left for 7.5 cm, to reach the level of the tenth costal cartilage across the front of the body of L3.

• Third part. This passes upwards and to the left for approximately 10 cm.

• Fourth part. This finally ascends for 2.5 cm to become continuous with the jejunum at the duodenojejunal flexure at the level of L2, 2 cm left of the mid line.

• Note. The common bile duct and pancreatic duct drain into the duodenum midway along its second part.

The small intestine

The small intestine is described in two parts, the first being termed the jejunum and the second, the ileum.

Palpation

surface marking

• The jejunum. The model is in the supine lying position. The jejunum begins as a continuation of the duodenum (Fig. 6.8a, b). It starts at the level of L2, 2 cm to the left of the midline and continues as the ileum.

• The ileum. This ends at its junction with the caecum (Fig. 6.9a, b) at the junction of the right mid-clavicular line with the transtubercular plane (drawn through the tubercles of the crest of the ilium). Each end is fixed in its position.

• Note. The central portion, which may be up to 8 m long, is continually mobile. It is, however, contained within the confines of the large bowel.

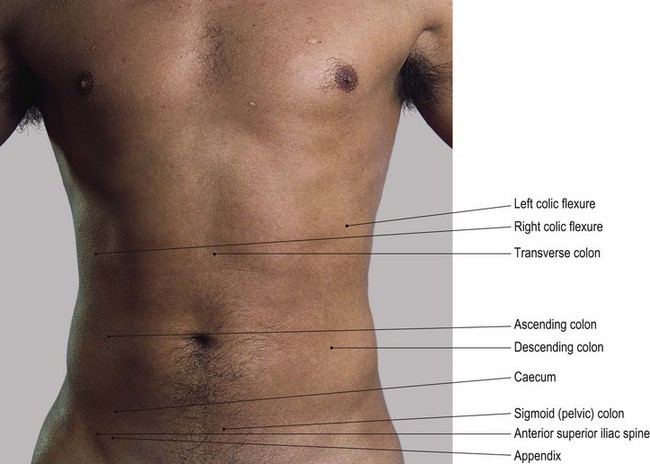

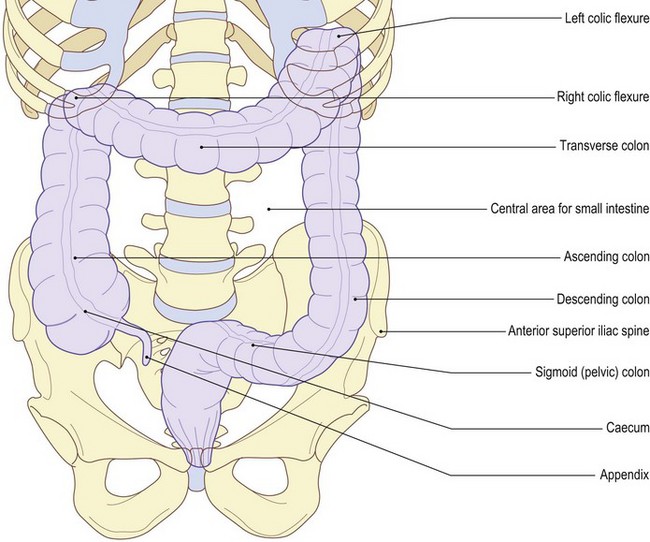

The caecum (Fig. 6.9a, b)

The caecum [caecus (L) = blind. Galen confused the caecum with the appendix]. This is the first section of the large intestine and receives the contents of the small intestine.

Palpation

surface marking

• The caecum. The model is in the supine lying position. The caecum fills the right iliac region of the abdomen. It lies above the lateral half of the right inguinal ligament.

• The appendix. This organ lies in the mid-clavicular line, 1.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine.

• Note. The caecum and appendix are not palpable, but pressure applied to this region can be extremely painful, particularly if the appendix is inflamed.

The large intestine (large bowel) (Fig. 6.9a, b)

For descriptive purposes, the large intestine is normally divided into four sections: ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid (pelvic). It can be represented by a band, approximately 5 cm wide, but varies considerably according to its contents.

Palpation

surface marking

• The ascending colon. The model is in the supine lying position. The ascending colon commences in the right iliac region at the caecum. It ascends through the right lumbar region, deep to the costal margin, to the level of the transpyloric plane. At the transpyloric plane it arches backwards and to the left, forming the right colic (hepatic) [hepar (Gk) = liver] flexure.

• The transverse colon. This section passes from the colic flexure, across the umbilical region below the liver towards the spleen. There it turns downwards, forming the left colic (splenic) flexure just above the transpyloric plane.

• The descending colon. This section passes through the left lumbar and iliac regions. It turns backwards at the inguinal ligament to become the sigmoid [sigma (Gk) = letter S, -oeides (Gk) = shape, form] colon.

• The sigmoid colon. This section passes backwards and downwards in an S-shaped curve to pass vertically downwards in front of the sacrum, becoming the rectum. This is continuous with the anal canal and reaches the surface at the anus.

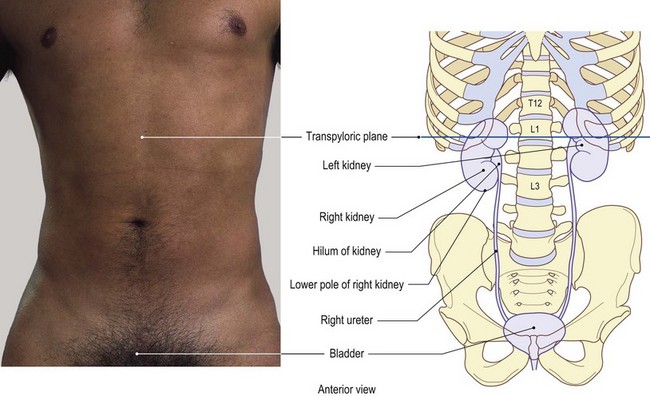

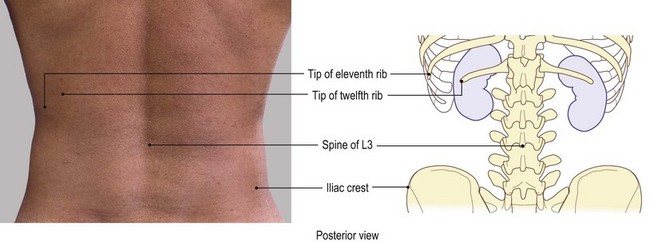

The kidneys (Fig. 6.10)

The kidneys are situated on the posterior abdominal wall anterior to quadratus lumborum behind the peritoneum. Each kidney lies obliquely with its anterior surface facing slightly laterally. The anterior relations of the right kidney are the right suprarenal gland and liver superiorly, the duodenum and right colic flexure inferomedially. The left kidney has the left suprarenal gland above, the tail of the pancreas and splenic vessels, the stomach and left colic flexure anteriorly, with the spleen postero-superiorly. Each kidney is related posteriorly to quadratus lumborum, the diaphragm and the medial and lateral arcuate ligaments. The right kidney lies mainly in front of the twelfth rib, while the left lies anterior to the eleventh rib. Each kidney is approximately 11 cm in length, 6 cm wide and 3 cm thick. The hilum lies level with the spine of the first lumbar vertebra (the transpyloric plane), the right normally slightly lower than the left.

Palpation

surface marking

• The kidneys: general points. The model is in the prone lying position. Each kidney can be located between two horizontal and two vertical lines, forming a rectangle on either side of the vertebral column. The upper and lower limits of both kidneys lie between horizontal lines through the upper margin of T12 above and L3 below.

• The kidneys. To facilitate the location of these lines, first draw a horizontal line through the lower edge of the spine of L1. Now draw a second line 5.5 cm above this (i.e. level with the upper border of T12). Then draw a third line 5.5 cm below (i.e. level with L3).

• Note. Because the two kidneys lie obliquely, the two vertical lines enclosing them are closer together than the width of the organ. Draw two vertical lines, one 3 cm and one 6.5 cm, lateral to the lumbar spines. These represent the medial and lateral margins of the kidneys.

Palpation

The kidneys are well protected, lying anterior to the lower ribs and strong back muscles, below the diaphragm. The vertebral column, with the attachments of the crura of the diaphragm, lies between the two kidneys and psoas major and minor lie behind them. The kidneys are protected in front by the large and small bowel and the powerful abdominal muscles. They are thus virtually impossible to palpate.

The bladder (Fig. 6.10a, b)

The bladder is a thin-walled muscular reservoir which varies in size according to the volume of fluid it contains. It is estimated that it is able to hold about 250 mL of urine before having to be emptied, but this estimate appears to be a little on the low side practically. Its volume obviously grows according to the frequency it is filled with large quantities of fluid.

• The bladder. The model is in the prone lying position. The bladder is situated directly behind the two pubic bones and pubic symphysis, with its upper border reaching to the crest on either side. When full, however, it rises above the pubic rami by up to 5 cm.

• Note. The empty bladder is not palpable in the normal subject but when full it can be felt as a soft swelling just above the pubic symphysis.