Chapter Eleven Observation

Introduction

Observation is a common method for data collection in both health research and clinical practice. Observation involves being close to things, such that the observer is in a position directly to perceive and record the phenomena under study. The advantage of observational data collection over questionnaires and interviews in research is that the researcher is in a position directly to see and hear what people actually do, rather than relying on the participants’ interpretations and perceptions of their actions.

Overview of different approaches to observation

Depending on the phenomenon being studied and the research questions being asked, one or more of a number of different observational approaches may be employed in the data collection. Each of these approaches has associated advantages and disadvantages. The basic issues are:

Who is to make the observations?

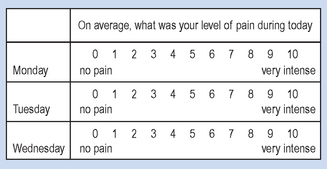

When research involves the observation of human subjects, self-observation becomes feasible and, at times, desirable. As an example, consider the study of pain. Here the patients themselves are uniquely positioned to provide subjective evidence concerning the intensity and location of pain over a period of time. Figure 11.1 shows a typical chart for guiding self-recorded pain observations in chronic pain patients, which is used in both research and clinical assessment.

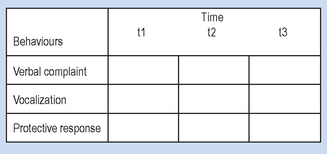

The self-observations of the patients provide data for understanding how patients’ pain experiences change over time, events correlating with the onset and offset of the pain and also evidence for evaluating the relative effectiveness of pain management strategies. Given that the experience of pain may be expressed in the sufferer’s overt behaviour, we may observe such pain-related behaviours when assessing pain. For instance, in a study involving comparison of pain behaviours of surgical patients with different cultural backgrounds, independent observers recorded pain-related behaviours in patients at agreed time intervals during physiotherapy treatments. Figure 11.2 is based on whether the observers recorded a yes or no for each category for each time interval in which the behaviours were sampled.

There are probable relative advantages and disadvantages to using self-observation or outside observers, as shown in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Advantages and disadvantages of using self-observation or outside observers

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-observation | ||

| Outside observer |

Settings in which observation is conducted

Some disciplines, such as astronomy or geography, focus on phenomena which are best studied as they occur, in their natural settings. Other disciplines, such as anatomy or chemistry, are more likely to be studied in a laboratory. In the broad range of health sciences research, phenomena are studied in either laboratory or natural settings, and observational data collection may be appropriate in both of these settings.

The general advantage of laboratory environments is that we can impose a considerable degree of control over extraneous variables which may systematically influence our observations. In addition, equipment for facilitating or recording observations is more readily available. For example, in the 1960s, Masters & Johnson began a series of studies to examine the physiology of the human sexual response. The controlled laboratory setting and the use of appropriate instrumentation enabled these researchers to observe and accurately record poorly understood aspects of human sexual functioning. This work was thought to be fundamental for developing clinically useful interventions aimed at helping people with sexual dysfunction, although it must be noted that this work has not been without controversy.

The disadvantage with laboratory settings is that the phenomenon being observed may change when it is being observed in an artificial setting. This is particularly true for human behaviour, where the social contexts are fundamental determinants of the behaviours and experiences. Indeed, the discipline of social psychology is devoted to the study of these effects. In other words, laboratory research sometimes has problematic ecological validity in that the findings discovered in this context may not generalize well to other contexts. Table 11.2 summarizes some of the relative advantages and disadvantages of laboratory and natural settings for making observations.

Table 11.2 Advantages and disadvantages of laboratory and natural settings for making observations

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory setting | ||

| Natural setting |

Unaided observation or the use of instrumentation

The accurate observation of a variety of phenomena is possible through the unaided senses; for example, observing aspects of human behaviour or clinical symptoms such as abnormal postures, discoloration of the skin, or abnormalities in patients’ eye movements. Other phenomena may be inaccessible to unaided observation such as, for example, very small objects and events, where we might need to use a microscope for accurate observations. Some events are also extremely complex and occur relatively quickly in relation to the observer. An example of this is human locomotion where recording the event using a device such as a video camera greatly enhances the accuracy of the observation. A fundamental reason for the advancement of science and clinical practice has been the development of sophisticated instrumentation.

There are, however, certain disadvantages associated with using instrumentation. These issues are discussed later in this book, when we review instrumentation and measurement. We can note here, however, that the use of instruments may distort the event being observed; for example, the preparation of tissue for electron microscopy changes to some extent the internal organelles of a cell being observed. It requires considerable expertise to use more complex instruments, and a strong theoretical background to separate the artefacts from useful data and interpret the observations. Human subjects also react to being observed. The more intrusive the observer is with equipment and instruments, the more likely that the subjects’ behaviour will change.

The use and relative advantages and disadvantages of recording techniques were discussed in the context of interviewing techniques earlier in the book. Table 11.3 represents the relative advantages and disadvantages of using instruments for aiding observations.

Table 11.3 The advantages and disadvantages of using instruments for aiding observations

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Unaided observations | ||

| Instrumentation |

Observer roles

Whether or not instrumentation is used as an adjunct, observation involves a person perceiving and recording an event. There are various positions observers may take in relation to observing human behaviour in health care settings. The fundamental issue is the extent to which the observer becomes involved or participates in the events being observed. There are generally considered to be four main roles that an observer may take. These are: complete participant, participant as observer, observer as participant and complete observer. These are discussed below.

The complete participant assumes the role of participant in the setting under investigation and does not normally disclose his or her intent to the other participants. Thus, the researcher actively participates in the setting without the knowledge or consent of the other participants. The purpose behind this approach is to minimize any changes in behaviour of the other participants as a result of their being observed. It can, however, border on the edge of unethical practice and must be used with caution. An example of the use of the complete participant method is provided by Rosenhan’s (1975) classic study of ‘pseudo-patients’ in psychiatric hospitals. Here, the observers posed as (and were admitted as) psychiatric patients in order to study the experiences of psychiatric patients. The pseudo-patients were not recognized as impostors by the staff or the institutions. In this way, they could make and record observations about the interpersonal interactions between the staff and patients. However, in order to be admitted, the observers deliberately misled the staff, who were in fact under study.

The participant as observer participates fully in the situation under study, but discloses his or her identity and purpose to the other participants. Examples of this can be seen in anthropological studies, where the observer attempts to participate as an active member of a cultural group.

The observer as participant makes no pretence of participation but interacts with the other participants. When using this method in a health setting, the observer obtains permission to record events and observe patients, while interacting with the staff and the patients. An example of this method is provided by a study performed by a PhD student with a nursing background, supervised by one of the authors. The student’s objective was to investigate how psychiatric nurses working in the community make decisions to act in a crisis situation with a disturbed person. He accompanied the nurses on their crisis visits. While travelling to the crisis scene, he interviewed the nurses about their expectations. He observed the crisis scene and its participants and, immediately following its conclusion, interviewed the nurses about it.

The complete observer does not interact with the other participants at all and, as with complete participation, does not disclose his or her identity or purpose. As an example, one might investigate therapist–patient interactions by observing from behind a one-way mirror. Observers can, if they wish, use a structured schedule for making the observations.

The level of participation chosen involves a tension between the requirements of objective and independent analysis, and the proximity from which the social and clinical phenomena can be studied. Clearly, the participation of the observer introduces changes in the phenomenon under study. It is a question of whether these changes are so large as to negate the benefits obtained by closer observation afforded by actual participation. This question has generated much discussion in the social, behavioural and clinical sciences.

Observation in qualitative field research

Observation data collection in the context of qualitative field research requires providing authentic pictures and reports of individuals functioning in their natural environments. Lofland (1971) outlined the following four important principles for conducting field research:

Lofland (1971) suggested that, when observing subjects in the context of field research, the investigator might focus on the following categories:

All pseudo-patients took extensive notes publicly. Under ordinary circumstances, such behaviour would have raised questions in the minds of observers, as, in fact, it did among patients. Indeed, it seemed so certain that the notes would elicit suspicion that elaborate precautions were taken to remove them from the ward each day. But the precautions proved needless. The closest any staff member came to questioning these notes occurred when one pseudo-patient asked his physician what kind of medication he was receiving and began to write down the response. ‘You needn’t write it’, he was told gently. ‘If you have trouble remembering, just ask me again.’

| Mary: | I used to hold my breath because my mother used to go on so quick and (pause). |

| Interviewer: | Moving you mean? |

| Mary | Yes. |

| Interviewer: | You mean your mother was |

| moving about the house quickly? | |

| Mary: | Yes and everything. |

| Interviewer: | And what did you do? |

| Mary: | Sort of stand like that. |

| Interviewer: | Can you demonstrate to me – sitting in a chair? |

| Mary: | Yes. I just sort of (shows what she did). |

| Interviewer: | With your elbows? |

| Laing & Esterson (1970) | |

The pseudo-patient behaved afterward as he normally behaved. The pseudo-patient spoke to patients and staff as he might ordinarily. Because there is uncommonly little to do on a psychiatric ward, he attempted to engage others in conversation. When asked by staff how he was feeling, he indicated that he was fine, that he no longer experienced symptoms. He responded to instructions from attendants, to calls for medication (which was not swallowed), and to dining-hall instructions. Beyond such activities as were available to him on the admissions ward, he spent his time writing down his observations about the ward, its patients, and the staff. Initially these notes were written secretly, but as it soon became clear that no one much cared, they were subsequently written on standard tablets of paper in such public places as the day-room. No secret was made of these activities.

Her absence of social life, her withdrawal, appears to be an unwitting invention of her parents that never seems to have been called into question.

| Ruth: | Well the places I like to go to my parents don’t like me to go to. |

| Mother: | Such as? |

| Ruth: | Eddie’s club. |

| Mother: | Oh, goodness. You don’t really – |

| Father: | ? |

| Ruth: | I do. |

| Interviewer: | What is ‘Eddie’s’? |

| Mother: | It’s a drinking club. She doesn’t really drink. It’s just that she likes to meet different types. |

| Interviewer: | She sounds as though the people that she does want to go out with are people she feels you disapprove of. |

| Mother: | Possibly. |

| Father: | Yes. |

| Mother: | Possibly. |

A stranger entering an ICU is at once bombarded with a massive array of sensory stimuli, some emotionally neutral but many highly charged. Initially, the greatest impact comes from the intricate machinery, with its flashing lights, buzzing and beeping monitors, gurgling suction pumps, and whooshing respirators. Simultaneously, one sees many people rushing around busily performing lifesaving tasks. The atmosphere is not unlike that of the tension-charged strategic bunker. With time, habituation occurs, but the ever-continuing stimuli decrease the overload threshold and contribute to stress at times of crisis.

As the newness and strangeness of the unit wears off, one increasingly becomes aware of a host of perceptions with specific stressful emotional significance. Desperately ill, sick, and injured human beings are hooked up to that machinery. And, in addition to mechanical stimuli, one can discern moaning, crying, screaming and the last gasps of life. Sights of blood, vomitus and excreta, exposed genitalia, mutilated wasting bodies, and unconscious and helpless people assault the sensibilities. Unceasingly, the ICU nurse must face these affect-laden stimuli with all the distress and conflict that they engender.

Observations of the above classes of behaviours and settings will provide a report representing individuals’ experiences and their interactions in a natural setting.

Observation in quantitative research

Research involving human subjects may be conducted using either qualitative or quantitative approaches. With non-human phenomena, quantitative approaches are obviously more relevant. The following are common features of observations in the context of quantitative research.

We have examined two different types of observation guides (shown in Figs 11.1 and 11.2). If they are to be useful for conducting observational data collection, considerable effort must be made in the design of such guides and in establishing their reliability and validity, as we shall see in the next chapter.

The advantages of an observation guide are that the recording of the observations is made simple, and the data are easily summarized and evaluated using descriptive and inferential statistics, as discussed in later chapters of this book. The disadvantage of highly structured observations (as with interview and questionnaire techniques) is that the spontaneity and uniqueness of certain events may be lost, to the extent that only predetermined categories are recorded.

Summary

Data collection based on observation is appropriate for a wide range of research designs, ranging from laboratory-based experiments to qualitative field research. A basic issue is the extent to which a structure is imposed on the observer. Highly structured observational frameworks are most suited for quantitative research while more loosely structured participant observation is better suited for qualitative research. In general, when making observations involving human subjects, researchers attempt to minimize subject reactivity and enhance the accuracy of recording the evidence. When appropriate, instrumentation may be used to enhance or record observations. It is worth noting that data collection using questionnaires, interviews and observations may well be used in combination in both research and clinical case work.

Self-assessment

Explain the meaning of the following terms: