Chapter 16 Assisted vaginal delivery and shoulder dystocia

INDICATIONS FOR INSTRUMENTAL ASSISTED VAGINAL DELIVERIES

The incidence of instrumental vaginal delivery should be between 8% and 10% of births.

REQUIREMENTS FOR ASSISTED DELIVERY

FORCES OPERATING IN THE SECOND STAGE OF LABOUR

Successful outcome for assisted delivery is governed by a dynamic balance between the passage, passenger and powers.

Passage and passenger

An accurate assessment of the passage and passenger begins with antenatal care and continues into the intrapartum period.

In the antenatal period, the fetus (or passenger) is continuously monitored for signs of intrauterine growth restriction or macrosomia. Fetal size, presentation, position, attitude and growth are assessed by a combination of abdominal and ultrasound examination.

The passage is assessed by clinical examination and magnetic resonance and radiological pelvimetry. Gross pelvic contracture can be detected, but usefulness of pelvimetry for predicting dystocia has been questioned.

Past obstetric history detailing modes of delivery for various birthweights allows estimation of fetal size against past performances to indicate likelihood of dystocia in the current pregnancy.

Gross cephalopelvic disproportion must be excluded before any attempt at assisted vaginal delivery. Minor degrees of disproportion are difficult to detect. Possible reduced pelvic diameters and/or a moderately big fetus forewarn likely borderline cephalopelvic disproportion and need for assistance.

Powers

Abdominal palpation and tocographic monitoring both detect frequency and duration of uterine contractions but not their intensity. Use of intrauterine pressure catheters for intensity of uterine contractions is not helpful in the management of dystocia.

The forces in the second stage for delivery are:

Maternal expulsive effort

Poor maternal effort is a common indication for assisted deliveries. Pushing is both exhausting and ineffective when it is not synchronised with uterine contractions Advise women to push to coincide with uterine contractions. They should rest between contractions to avoid getting tired.

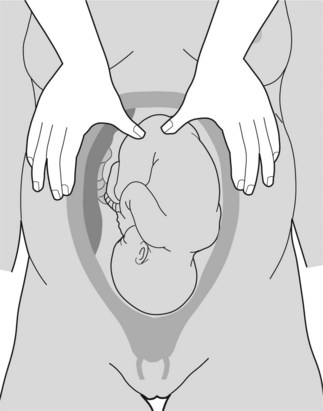

Fundal pressure

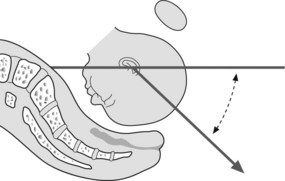

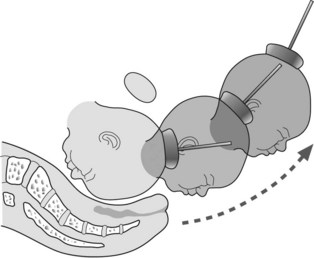

Fundal pressure is used during caesarean births and assisted deliveries (see Figure 16.1). Pressure is applied at the uterine fundus (usually over the buttocks of the fetus) along its longitudinal axis to coincide with uterine contractions and maternal expulsive efforts. Fundal pressure should not be applied in between contractions particularly when maternal effort is absent.

ASSISTED DELIVERY

Assistance should be in synchrony with expulsive forces to overcome soft tissue resistance in the second stage of labour, usually for delivery of the fetal head. Resistance arises from individual difference in pelvic musculo-fascial soft tissue, perineal tissue compliance and to some degree moulding of the fetal head.

Informed consent

Assisted vaginal delivery is an operative procedure with attendant risks and complications, and therefore requires detailed discussion with the woman and her partner. Consent, usually verbal, is often obtained just before an emergency procedure from a distressed woman. Although necessarily brief, discussion and counselling are essential. A more detailed discussion should follow to debrief and answer questions.

Instruments for assisted delivery

Forceps

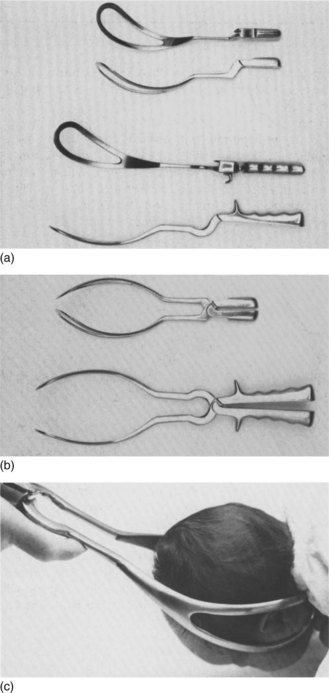

Description of forceps

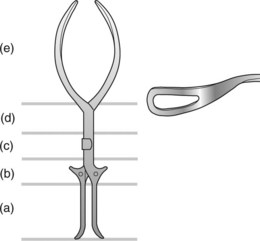

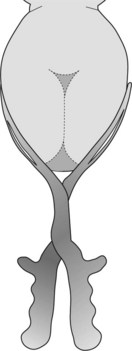

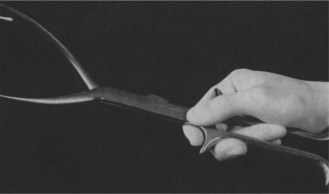

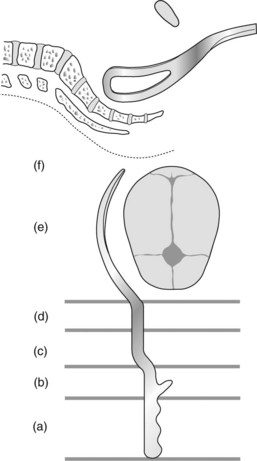

Each forceps has a left and right fenestrated blade. Each traction blade has a cephalic curve for the fetal head and a pelvic curve to accommodate the curvature of the maternal pelvis. When joined as a pair through a fixed lock, these blades form a protective cage which surrounds the fetal head without compression. When traction is applied, pressure transmitted to the fetus is safely contained by the firm fetal malar bones (Figures 16.2, 16.3).

Figure 16.3 Traction forceps illustrating (a) handle (b) shoulder, (c) lock, (d) shank, (e) blade with cephalic curve and (f) pelvic curve.

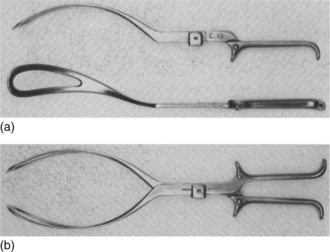

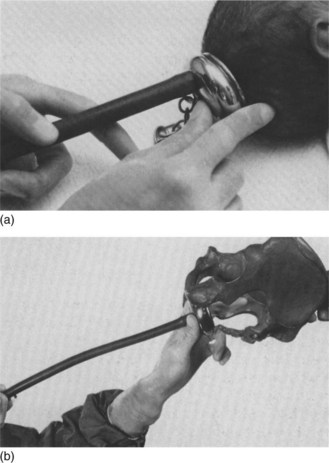

Kjelland’s rotational forceps differs from traction forceps. The shank is long and the blade is thin. The modest pelvic curve allows rotation through a much smaller circumference. The sliding lock allows application when asynclitism is present (see Chapter 19). Knobs on the handles point towards the occiput (also known as occipital knobs) (Figures 16.4-16.6).

Vacuum extractors

Description of vacuum extractor

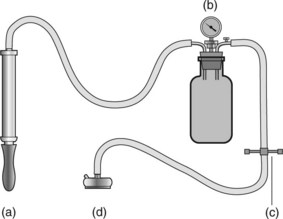

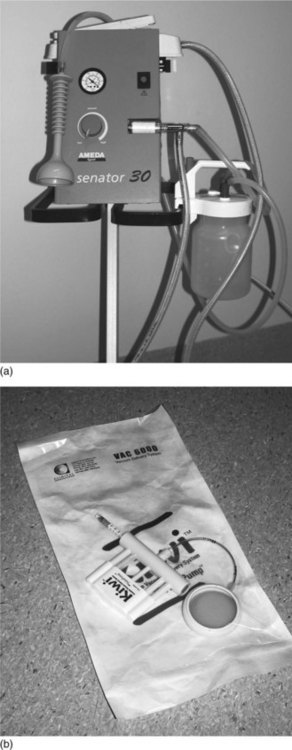

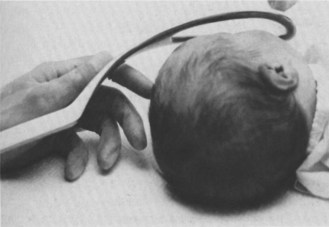

The principal components of the vacuum extractor are the pump, the pressure gauge, the traction piece and the cup used to raise the chignon for traction (Figure 16.7). Figure 16.8 shows a contemporary ventouse extraction and delivery system.

Choosing between forceps and vacuum extraction for assisted deliveries

Contemporary reviews found that vacuum extraction was associated with significantly less maternal trauma than forceps delivery. Fewer caesarean sections were carried out in vacuum extractor groups. However, the vacuum extractor was associated with an increase in neonatal cephalhaematoma and retinal haemorrhages. Forceps were associated with a lower failure rate. The chief disadvantage of forceps is a higher risk of significant maternal perineal injury, especially anal sphincter injuries.

Neither instrument is superior for assisted vaginal deliveries. The forces and requirements for either form of assisted delivery are similar. The choice of instrument depends on the clinical scenario as well as the operator’s experience, training and preferences. Both instruments are equally suited to most assisted deliveries. In circumstances where cephalopelvic disproportion is confidently excluded and speed is of essence (e.g. ominous cardiotocographic tracing), forceps may be the instrument of choice for expediting delivery. The vacuum extractor may be preferred where asynclitism is present, when rotational delivery is needed and there is limited experience with forceps. There is no increased morbidity in completing a delivery by forceps when the vacuum fails provided that the requirements for assisted delivery are fulfilled. Table 16.1 shows a comparison between the two types of instrumental delivery. The long-term outcome is the same for mother and child.

Table 16.1 Instrumental vaginal delivery

| Forceps | Vacuum | |

|---|---|---|

| Popularity | Decreased | Increased |

| Preterm | Yes | Not before 36 weeks |

| Undilated cervix (around 9 cm) | Contraindicated | Yes |

| Anaesthesia | Yes | Need less |

| Failure to achieve delivery | Less likely | More likely |

| Tissue trauma | Possible | Less |

| Cephalhaematoma | Possible | More likely |

| Retinal haemorrhage | Possible | More likely |

| Postpartum perineal pain | Yes | Less |

TRACTION PROCEDURES

Box 16.1 describes the types of traction procedure used in assisted delivery.

Box 16.1 Traction procedures used in assisted delivery

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) classification of forceps deliveries 2000

Outlet procedure refers to the application of the instrument when:

Low procedure refers to the application of the instrument when:

Mid-pelvic procedure refers to the application of the instrument when:

Before application of instruments

During the use of instruments

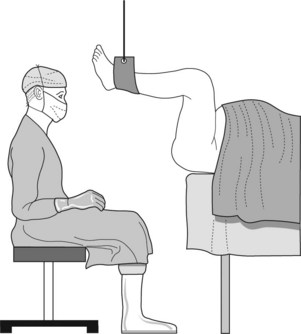

Figure 16.9 Position of an obstetrician for forceps delivery. The woman’s legs are suspended by stirrups or other means.

Box 16.2 Application of instruments

Forceps

Vacuum

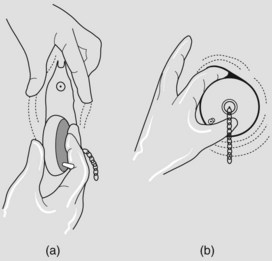

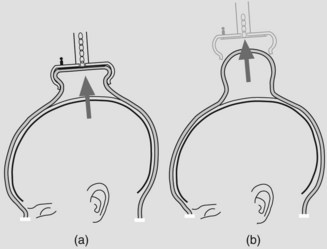

Figure 16.12 (a) Formation of a chignon to assist traction (b) with residue swelling persisting for 24–48 hours after cup is removed.

For forceps

For vacuum

Delivery of the baby

The rest of the delivery is the same as that for normal birth.

Procedures after delivery

ROTATIONAL PROCEDURES

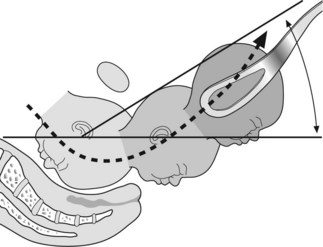

A wider diameter is presented when the vertex is in the occipitolateral or occipitoposterior position. Rotation into the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet may occur on the perineum or at any level between the ischial spines and the perineum. Delivery in the occipitoposterior position may increase perineal trauma unless carefully conducted.

The three most common techniques used for placing the vertex into the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet are:

Requirements

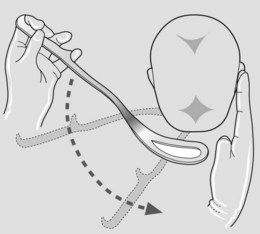

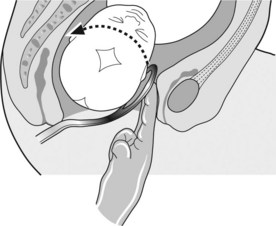

Manual rotation

This is a safe technique. Pressure on the fetal head is easy to judge and trauma to soft tissue is less likely. Check cervical dilatation and adequacy of pelvis.

Technique

Ventouse rotation

Technique

Rotation by Kjelland’s forceps

Designed for rotation, the shank is long and the blade thin. There is no pelvic curve so rotation is through a smaller circumference. The sliding locks allow application when asynclitism is present (see Figures 16.5, 16.6).

Application by wandering anterior blade

Application by the direct method

Rotation and delivery

Inherent dangers of Kjelland’s forceps

There are two inherent dangers in the design of the Kjelland’s forceps. Firstly, the thin blades can cause considerable soft tissue trauma. Secondly, the wandering technique necessitates moving the blades over a large area of vagina. This increases the risk of trauma. Whether Kjelland’s forceps should continue to be used is controversial.

Trial of forceps or vacuum

MATERNAL COMPLICATIONS

Assisted vaginal delivery is associated with the following maternal complications:

NEONATAL COMPLICATIONS

Assisted vaginal delivery is associated with the following neonatal complications:

MEDICoLEGAL ISSUES

Instrumental vaginal delivery followed by complications or poor fetal outcome is a ready situation for complaints and litigation. The following are important from the perspective of clinical governance and risk management:

SYMPHYSIOTOMY

This procedure is seldom used but can be effective for delivery if the aftercoming head of a normal live breech is stuck at the pelvic outlet. Requirements are:

SHOULDER DYSTOCIA

The term shoulder dystocia describes difficulty with delivery of the shoulder after delivery of the fetal head. This unpredictable emergency occurs in 0.5–2% of vaginal deliveries. The complication is usually due to the anterior shoulder becoming stuck above the symphysis pubis (unilateral dystocia). Bilateral dystocia is when both shoulders are impacted above the pelvic inlet. Shoulder dystocia results from failure of the shoulder to rotate to the transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet followed by 90° rotation to the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet.

Management

Antenatal

Intrapartum

All labour ward medical staff must be regularly ‘drilled’ to become practised in managing this emergency. Assess all women admitted for delivery. If risk is suspected make sure an experienced obstetrician attends delivery. When this emergency arises activate the following steps.

HAEMATOMAS

A shearing action between the vagina and deeper tissues during normal, assisted or rotational delivery can rupture the vaginal plexus of veins to form a haematoma. If extensive, this will involve the paravaginal space, the labia, urethra and even extension into the broad ligament. Inadequate haemostasis following episiotomy repair or closure of the caesarean section wound also result in haematoma formation.

BLADDER FUNCTION AND CARE DURING LABOUR AND AFTER DELIVERY

Labour and particularly delivery can potentially affect pelvic floor musculature and nerves causing urinary and bowel dysfunction. Contributory factors include nulliparity, prolonged labour, epidural anaesthesia with bladder overdistension, instrumental delivery and vaginal or perinatal trauma.

In labour

Acker DB, Sachs BB, Friedman EA. Risk factors for shoulder dystocia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985;66:762-766.

Bahl R, Strachan B, Murphy DJ. Outcome of subsequent pregnancy three years after previous operative delivery in the second stage of labour – cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328:311-314.

Cardozo L, Gleeson C. Pregnancy, childbirth and continence. British Journal of Midwifery. 1997;5:277-281.

Chan CCT, Malathi I, Yeo GS. Is the vacuum extractor really the instrument of first choice?. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;39:305-309.

Cheung YW, Hopkins IM, Caughey AB. How long is too long: does a prolonged second stage of labour in nulliparous women affect maternal and neonatal morbidity?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191:933-938.

Drife JO. Choice and instrumental delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;103:608-611.

Dupuis O, Madelenat P, Rudigoz RC. Faecal and urinary incontinence after delivery: risk factors and prevention. Gynaecology Obstetrics Fertility. 2004;32:540-548.

Eustice S. Management of voiding difficulties associated with pregnancy. Nursing Times. 2004;100:50-53.

Fortune PM, Thomas RM. Sub-aponeurotic haemorrhage: a rare but life-threatening neonatal complication associated with ventouse delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:868-870.

Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Soutar I, et al. The McRoberts’ manoeuvre for elevation of shoulder dystocia: how successful is it?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;176:656-661.

Gonen R, Spiegel D, Abend M. Is macrosomia predictable, and are shoulder dystocia and birth trauma preventable?. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;88:526-529.

Gonen O, Rosen DJ, Dolfin Z, et al. Induction of labour versus expectant management in macrosomia: a randomised study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;89:913-917.

Johanson RB, Heycock E, Carter J, et al. Maternal and child health after assisted vaginal delivery: five year follow up of a randomised controlled study comparing forceps and ventouse. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:544-549.

Johnstone FD, Myerscough PR. Shoulder dystocia. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:811-815.

Jolley S. Intermittent catheterisation for post operative urinary retention. Nursing Times. 1997;93:46-47.

Leaphart WL, Meyer MC, Capeless EL. Labour induction with a perinatal diagnosis of fetal macrosomia. Journal of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. 1997;6:99-102.

Leather AT. The management of shoulder dystocia. Contemporary Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;5:61-64.

Louise DF, Raymond RC, Perkins MB, et al. Recurrence rate of shoulder dystocia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;172:1369-1371.

Luria S, Benarie A, Hugay Z. The ABC of shoulder dystocia management. Asia Oceania Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;20:195-197.

Morales R, Adair CD, Sanchez-Ramos L, et al. Vacuum extraction of preterm infants with birthweights of 1,500–2,499 grams. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1995;40:127-130.

Nesbitt TS, Gilbert WM, Herrchen B. Shoulder dystocia and associated risk factors with macrosomic infants born in California. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;179:476-480.

Petroikovksy B. Emergency symphysiotomy: too little too late. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;178:631-632.

Rane A, Frazer M. Intrapartum and post partum bladder care. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology;. 1999;1:311-313.

Schwartz BC, Dixon DM. Shoulder dystocia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1958;11:468-471.

Sultan AA, Johanson RB, Carter JE. Occult anal sphincter trauma following randomised forceps and vacuum delivery. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;61:113-119.

Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, et al. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341:1709-1714.

Vacca A. The trouble with vacuum extraction. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;9:41-45.

Vasket TF, Allen AC. Perinatal implication of shoulder dystocia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;86:142-147.

Yips K, Sahota D, Pang MN, et al. Post partum urinary retention. Acta Obstetrica et Gynaecologica Scandinavica. 2004;85:881-891.