Chapter 17 Caesarean section

Caesarean section describes the surgical procedure for delivery of the fetus by incisions through the abdomen and uterus. The attendant risk of a surgical procedure must be considered. In the UK direct deaths following all caesarean sections is 82.3 per 1 000 000. For elective procedures this is 38.5 per 1 000 000. Death rate following vaginal delivery is 16.9 per 1 000 000 maternities (Department of Health (DoH) 2001). Pulmonary embolism, hypertension haemorrhage and sepsis continue to be salient causes of mortality. Inappropriate delegation, inadequate facilities and poor communication contribute to substandard care and necessitate improvement.

Sequelae of vaginal birth such as rectal and urinary incontinence, the question of choice, increased safety for caesarean section, more older women having babies and ready redress to litigation for complications with operative vaginal deliveries are factors leading to an increase in the rates of caesarean sections.

INDICATIONS FOR CAESAREAN SECTION

Caesarean sections can be subdivided into elective, scheduled or planned of varying emergency, unplanned emergency and peri-mortem and post-mortem categories to facilitate audit. Clearly complications and mortality attributed to the surgical procedure must be distinguished from contributions by obstetric complications and maternal medical problems.

Caesarean sections are performed to:

PREOPERATIVE CARE

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Presence of obstetric or medical complications mean some women will need close observation following caesarean section. The labour ward can serve as an area for recovery and care. Intensive or high dependency care facilities must be readily available in the same hospital. General care for all women includes:

TYPES OF INCISION

Abdominal incisions

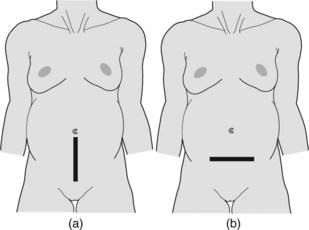

Essentially these are the subumbilical midline and transverse lower abdominal incisions (Figure 17.1).

Subumbilical midline incision

This incision is easy and quick. Access is good with minimal bleeding. It is useful when access to the lower segment is difficult, for example severe kyphoscoliosis or anterior lower segment fibroid. The scar however, is unsightly, there is more postoperative discomfort and dehiscence is more likely compared with transverse incisions.

Where extension upwards into the abdomen is likely a left or right paramedian incision can be performed.

Transverse (Pfannenstiel’s) incision

This is the current incision of choice. It is cosmetically pleasing, is less likely to dehisce and being less uncomfortable, allows better postoperative mobility. The incision can be technically more difficult especially in repeat surgery. It can be associated with greater blood loss and poorer access.

Variations include the Joel Cohen incision (placed higher up the abdomen) and Misgav Ladach (emphasises preservation of anatomical structures).

Uterine incisions

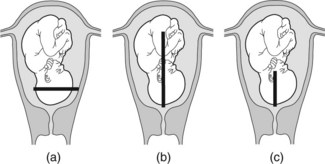

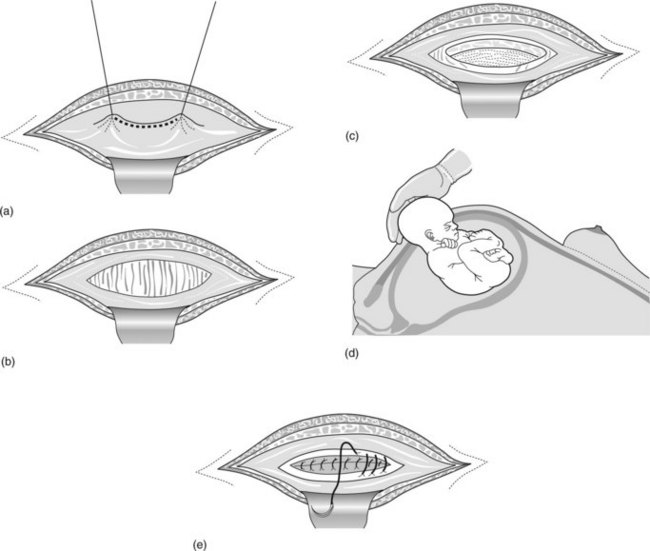

Entry into the uterus can be through a midline or a transverse lower segment incision (Figure 17.2).

Lower segment caesarean section (Figure 17.2a)

This is the most common approach. The transverse incision is placed in the lower segment of the gravid uterus behind the uterovesicle peritoneum. Advantages include:

Classical caesarean section (Figure 17.2b)

This incision is placed vertically in the midline of the uterine body. Indications for use include:

Krönig–Gellhorn–Beck incision (Figure 17.2c)

This is a midline incision in the lower segment. It is used in preterm deliveries where the lower segment is poorly formed or in situations where extension into the upper uterine segment is anticipated to provide more access. It has fewer of the complications associated with a classical Caesarean section. This incision need not preclude vaginal delivery.

Other situations

An inverted T incision or a J incision may on occasion be required when access is found to be inadequate despite a lower segment incision.

These incisions are best avoided. Like classical caesarean sections subsequent pregnancies will need to be delivered by elective caesarean section.

OPERATIVE STEPS FOR CAESAREAN SECTION

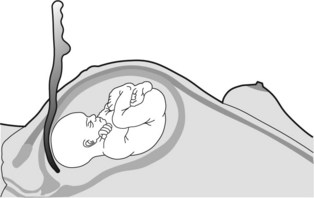

Figure 17.3 The peritoneum is (a) picked up and opened (b) before the lower segment is incised transversely (c). The fetal head (d) is delivered and the uterine wound is closed in two layers (e).

See Box 17.1 for a summary of the dos and do nots of caesarean section.

Box 17.1 Dos and do nots of caesarean section

Do

CAESAREAN SECTION: SPECIFIC ISSUES

Communication

Apart from issues of consent and good practice of forewarning team members such as anaesthetists and neonatologists it is important to define the degree of urgency for need to deliver the baby. In an emergency the current accepted decision to delivery interval is 30 minutes or less. This is however, not an evidence-based standard. Regular drills will ensure smooth assembly for urgent surgical delivery.

Vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC)

Vaginal delivery is contraindicated after a classic caesarean section and if there is need to extend the transverse uterine incision (T, J incisions). Where there is no recurrent indication for caesarean section, vaginal delivery reduces maternal mortality and morbidity. There is however, a 0.3% rate of uterine rupture associated with trial of scar. There is 25% perinatal mortality and a 25% need for hysterectomy following uterine rupture. Although a quarter to a third of women with prior caesarean section can successfully deliver vaginally, the following must be satisfied.

Signs of uterine scar rupture

Mothers with a classic uterine scar may experience uterine rupture prior to onset of labour. The low vertical uterine incision does not contribute an increased risk to uterine rupture compared with the low transverse uterine incision. Signs of uterine rupture are:

Management for uterine rupture

Maternal mortality for uterine rupture was 2.3 per 1 000 000 maternities (Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom, 1994–1996). Correct planning of delivery and induction (judicious prostaglandin usage after one dose), delivery in an appropriate setting, and involvement of experienced obstetric staff in intrapartum care can contribute to improved outcome.

Caesarean section after intrauterine fetal death

This is necessary when vaginal delivery is not feasible (for example impacted shoulders, fetal abnormality) or for the mother’s welfare (for example abruptio placentae, with severe bleeding and fetal death). Exclude coagulation defects. Additional psychological support will be required.

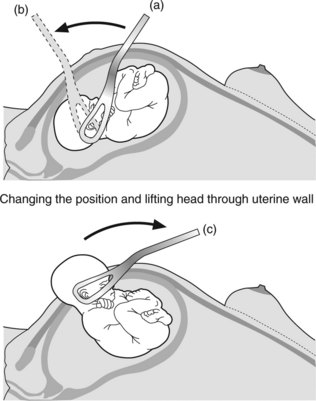

Difficulty with delivery of the fetal head

Caesarean section following a trial of labour or trial of forceps may find the fetal head impacted or deep in the pelvis. Delivery of the presenting part is facilitated by:

Caesarean hysterectomy

Indications include gross uterine rupture or uncontrollable haemorrhage. The woman’s condition is usually compromised hence speed and experience are required. Consider the following:

Classical caesarean section

Remember to check the rotation of the uterus. If possible start at the lower half of the upper uterine segment and extend if required. The uterine wall should be closed in three layers. The herringbone suture technique for closure of the superficial layer minimises oozing.

Holding stitch

Sterilisation

Department of Health. Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 1997–1999. London: HMSO, 2001.

Department of Health. Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom, 1994–1996. London: HMSO, 1998.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Report of the Working Party on Prophylaxis Against Thromboembolism in Gynaecology and Obstetrics. London: RCOG Press, 1995.

Appleton B, Targett C, Rasmussen M, et al. Vaginal birth after Caesarean section. An Australian Multicentre Study. VBAC Study Group. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;40:87-91.

Bergsjo P. Quality assurance: a concept rediscovered. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1993;72:143.

Caughev AB, Shipp TD, Repke JT, et al. Rate of uterine rupture during a trial of labour in women with one or two prior Caesarean deliveries. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;181:872-876.

Chazotte C, Cohen WR. Catastrophic complications of previous Caesarean section. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;163:738-742.

Donald I. Practical Obstetric Problems. London: Lloyd-Luke (Medical Books) Ltd, 1979.

Duff P. Prophylactic antibiotics for Caesarean delivery. A simple cost-effective strategy for the prevention of post-operative morbidity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;157:794-798.

Gregory KD, Korst LM, Cane P, et al. Vaginal birth after Caesarean and uterine rupture rates in California. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;94:985-989.

Guise JM, McDonagh MS, Osterweil P, et al. Systemic review of the incidence and consequences of uterine rupture in women with previous Caesarean section. BMJ. 2004;329:1-7.

Malkasian GD. The conscience of the specialty. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;75:1-4.

Martens MG, Faro S, Philips LE, et al. Postpartum endometritis in high risk C section patients. Surgical Infections. 1987;6:96-99.

Miller DA, Fidelia GD, Paul RH. Vaginal birth after Caesarean section. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335:689-695.

Molmgren G, Sjoholm L, Stark M. The Misgav Ladach method for Caesarean section: method description. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1999;78:615-621.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Guideline 15: Peritoneal closure. London: RCOG, 1998.

Royal College of Obstetrician and Gynaecologists. Guideline 4: Male and female sterilization. London: RCOG, 2004.

Shipp TD, Zelop CM, Repke JT, et al. Intrapartum rupture and dehiscence in patients with prior lower uterine segment. Vertical and transverse incisions. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;94:735-740.

Smith GC, Pell JP, Pasupathy D, et al. Factors predisposing to perinatal death related to uterine rupture during attempted vaginal birth after Caesarean section: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;329:275-379.

Sood AK, et al. Pregnant women with cervical cancer should be delivered by caesarean section. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;95:832-838.

Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Mayr N, et al. Cervical cancer diagnosed shortly after pregnancy: Prognostic variables and delivery routes. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;95:832-838.