Chapter 9 Analgesia and anaesthesia

Obstetric analgesia is the relief of pain in labour; anaesthesia is the abolition of sufficient sensation to allow operative delivery.

The experience of pain represents a complex combination of physiological, psychological, emotional and conditioned responses. Modern regional blocks can relieve pain in labour while preserving some sensation of uterine contractions and the ability to push. If instrumental delivery or caesarean section become necessary, it is possible to produce surgical anaesthesia rapidly by extension of the block. In the vast majority of cases general anaesthesia can be avoided.

General anaesthesia is nowadays reserved largely for those cases where a regional block is either contraindicated or has failed.

ANALGESIA FOR LABOUR

Inhalational analgesia

In the UK, 60–70% of labouring women seek to achieve analgesia by inhalation of a 50 : 50 mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen (N2O/O2). Marketed as Entonox and Equanox, the gas mixture is supplied in cylinders with blue body and blue/white shoulders and is piped to delivery rooms in many hospitals.

The gas is self-administered by inspiration through a facemask or mouthpiece, which opens a demand valve. Diffusion from alveoli to pulmonary capillaries and delivery to the brain by the cardiac output is not instantaneous – inhalation should start as soon as a contraction begins so maximum effect is achieved at its peak (see Chapter 7, Box 7.3).

The drug is non-cumulative, and does not affect the fetus. N2O/O2 causes a variable degree of sedation. Some women appear to be dreaming or drunk; others become somnolent or even briefly unarousable. Hyperventilation with N2O/O2 can be followed by a short period of apnoea, therefore the woman should hold the mouthpiece or mask herself. If she loses consciousness, she will let go. A few breaths of air eliminate the N2O and consciousness will invariably be regained soon. A number of studies have questioned the analgesic effect of N2O/O2. Pain is still perceived under the influence of the drug – it is merely rendered more bearable by the intoxicated state.

The risk of cross-contamination between women sharing breathing systems dictates that mouthpieces and masks should be disposable or sterilised between users. Either a new disposable breathing system should be used for each woman, or a disposable breathing system filter interposed between the tubing and mouthpiece/mask.

Parenteral opioids

Clinical studies of pain scores have cast doubt on the analgesic efficacy of opioids in labour. The drugs are certainly sedative, inducing a feeling of disorientation and thereby making pain more tolerable. All opioids can induce maternal and neonatal respiratory depression (decreased Apgar and neurobehavioural scores). Gastric emptying is inhibited, and the incidence of nausea and vomiting increased.

Midwives can prescribe and administer controlled drugs in accordance with locally agreed policies and procedures. In the UK, pethidine is the most widely used intramuscular opioid. A usual dose of 100 mg lasts around 3 hours. Plasma pethidine concentrations are maximal in the neonate when the mother has received the drug about 3 hours before delivery. It is therefore illogical to withhold the drug if delivery is imminent, for fear of causing neonatal respiratory depression.

Naloxone is a specific opioid antagonist. The neonatal dose is 10 μg/kg intramuscularly, repeated if necessary.

Comparisons of pethidine 100 mg with diamorphine 5 mg, meptazinol 100 mg and tramadol 100 mg have failed to demonstrate any convincing benefits. An antiemetic (e.g. cyclizine 50 mg or prochlorperazine 12.5 mg) should be given intramuscularly along with whatever the chosen opioid. Because of the additive risk of respiratory depression, intramuscular opioids should never be given in the event of inadequate regional analgesia without prior reassessment of the woman by an anaesthetist.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

Electrical impulses applied to the skin via flexible carbon electrodes from a battery-powered stimulator modulate the transmission of pain by closing a ‘gate’ in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The effect is similar to massage of the lower back by a birthing partner.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is used in about 1 in 20 labours in the UK. The technique is completely free from adverse effects, and can diminish the need for other analgesic interventions.

A study comparing TENS and ‘sham’ TENS’ (TENS devices which appeared to be working but had been disabled) failed to demonstrate reduced pain scores in labour. After delivery, however, those women who had had working TENS retrospectively rated their analgesia more highly. More of these women stated they would choose TENS again in a future labour.

Regional analgesia for labour

Regional analgesia is the provision of pain relief by blockade of sensory nerves as they enter the spinal cord. Local anaesthetic can be introduced into the epidural or subarachnoid (intrathecal) space, or both.

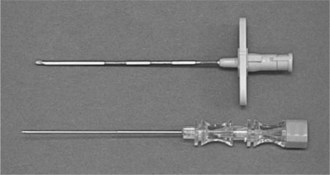

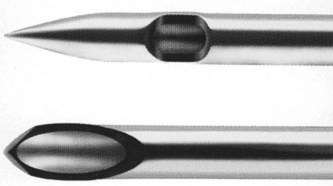

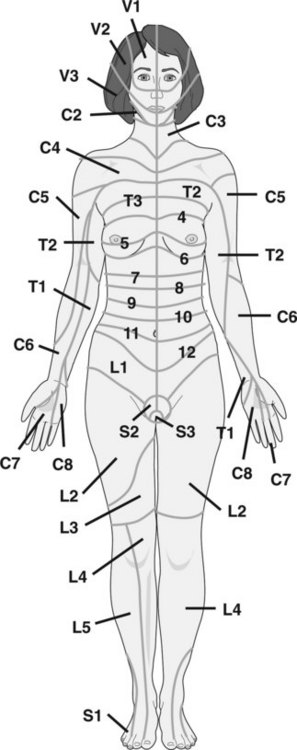

The epidural space is identified by the loss of resistance to depression of a syringe plunger as a Tuohy needle is advanced (Figure 9.1) through the ligamentum flavum. A catheter is then threaded through the Tuohy needle (Figure 9.2) to facilitate top-ups or continuous infusion. The subarachnoid space (containing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)) is a few millimetres deeper, inside the meninges. Needles used for spinal injection are much finer than Tuohy needles (Figure 9.3). A significant advance has been the development of ‘pencil point’ tips (Figure 9.4). Compared with standard cutting bevel or Quincke needle tips, the leak of CSF and likelihood of consequent headache are vastly reduced.

Figure 9.2 Tuohy needle advanced through the ligamentum flavum, with a catheter in the epidural space.

A trained anaesthetist must always be immediately available whenever regional analgesia is provided. Regional techniques improperly administered can be as hazardous as any general anaesthetic. Resources that should be available on every labour ward in the event of complications (see below) which might arise during the provision of regional analgesia are listed in Box 9.1.

Compared with every other analgesic technique, pain relief from regional blockade is undoubtedly superior. In the UK, 90% of consultant obstetric units provide a 24-hour epidural service; the average epidural rate is 24%.

Blockade of motor fibres causes relaxation of pelvic floor muscles and impairs expulsive efforts, therefore provision of adequate maternal analgesia with as little motor block as possible has emerged as a goal common to all regimens. Intermittent epidural boluses, continuous epidural infusions, and patient-controlled epidural analgesia all provide comparable pain relief and maternal satisfaction.

Unlike local anaesthetics, which prevent conduction of nerve impulses, opioids act on specific receptors in the spinal cord. Synergistic mixtures of local anaesthetic and opioids (usually fentanyl) have permitted significant reductions in the amount of local anaesthetic used. Side effects specific to the use of opioids are respiratory depression (in the most unlikely event that opioid spreads cephalad to reach the brainstem) and pruritus.

Combined spinal-epidural analgesia entails an initial subarachnoid injection of fentanyl mixed with a tiny amount of local anaesthetic. The resulting motor block is sufficiently minimal for women to retain sufficient muscle power to walk in labour. However, proprioception (information from joint receptors to maintain balance) can be impaired. In the absence of any proved advantage to mother or baby of walking in labour, some argue that it is hard to justify the risk of falling.

Signed consent is not necessary for regional analgesia in labour. Verbal consent is sufficient, and a brief record should be made in the notes of the risks/benefits that have been discussed.

Table 9.1 outlines the contraindications to regional analgesia, together with the associated risks.

Table 9.1 Contraindications to regional analgesia, with associated risks

| Contraindication | Risk |

|---|---|

| Uncorrected anticoagulation or coagulopathy | Vertebral canal haematoma |

| Local or systemic sepsis (pyrexia >38 °C not treated with antibiotics) | Vertebral canal abscess |

| Hypovolaemia or active haemorrhage | Cardiovascular collapse secondary to sympathetic blockade |

| Maternal refusal | Legal action |

| Lack of sufficient trained midwives for continuous care and monitoring of mother and fetus for the duration of the regional block | Maternal collapse, convulsion, respiratory arrest; fetal compromise |

A full blood count (FBC) is not required unless antepartum bleeding has occurred, anaemia is suspected, or there is evidence of pre-eclampsia. If the platelet count is normal, a coagulation screen is not necessary. If a pre-eclamptic woman’s overall condition is deteriorating an FBC should have been processed no more than 2 hours before a regional block is undertaken. If platelet count is 70–100 × 109/l or if the trend is steadily downwards, a coagulation screen must be normal if spinal/epidural block is to be undertaken. Petechiae or platelet count <70 × 109/l are indications for platelet transfusion. Aspirin therapy alone is not a contraindication to regional analgesia.

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) pose the risk of vertebral canal haematoma and consequent spinal cord or nerve root compression. This risk has to be weighed against the risk of emergency general anaesthesia in a woman denied regional blockade. As far as possible, institution of regional blocks – and removal of epidural catheters – should be undertaken when anti-factor Xa activity is least. After delivery, continued vigilance for signs of haematoma is essential. If symptoms of leg weakness or numbness, back pain, or bowel/bladder dysfunction develop (onset can be delayed beyond 24 hours) neurological/neurosurgical advice should be sought without delay.

Although a vertebral canal haematoma or abscess is exceedingly rare, transient neuropathy has an incidence of about 1 in 2000. Women can be reassured that epidural analgesia does not cause new, long-term backache.

All women should be warned about the possibility of dural tap – the inadvertent tearing of the meninges by the Tuohy needle or epidural catheter, which should have an incidence of <1%. This complication can predispose to two potentially serious sequelae: total spinal anaesthesia, and post-dural puncture headache (PDPH). The vast majority of pregnant women who develop PDPH will require an epidural ‘blood patch’. Other points worthy of explanation before performing a regional block in labour are listed in Box 9.2.

Box 9.2 Counselling before regional block

Before starting a regional block in labour inform women about:

The rate of cervical dilatation, duration of second stage and the instrumental delivery rate are similar when epidural analgesia is established before or after 4 cm cervical dilatation. Regional analgesia does not result in an increase in the overall caesarean section rate or the rates specific for dystocia or fetal distress. However, a significant proportion of those women who undergo caesarean section for dystocia will have had epidural analgesia for labour. Risk factors for dystocia produce painful labour and a desire for epidural analgesia.

It is well worth explaining in advance to women with risk factors for operative delivery that analgesia for labour can be converted to effective anaesthesia to facilitate forceps or caesarean delivery. Some women need time to consider the notion of being awake for a caesarean section.

Complications of regional analgesia

The two principal potential complications of epidural injection of local anaesthetic are local anaesthetic toxicity and total spinal anaesthesia. Aspirating the catheter to exclude intravenous or subarachnoid placement can prevent both. The delivery of local anaesthetic to the brain and heart by the bloodstream causes the symptoms and signs of toxicity (Table 9.2).

Table 9.2 Symptoms and signs of local anaesthetic toxicity

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

| Numbness of tongue or lips | Slurring of speech |

| Tinnitus | Drowsiness |

| Light-headedness | Convulsions |

| Anxiety | Cardiorespiratory arrest |

Epidural venous engorgement in the obstetric patient predisposes to blood vessel puncture in up to 1 in 5 epidurals. If blood is aspirated, flush with saline and withdraw the catheter by another 1 cm. If blood is still present, re-site at another interspace. Local anaesthetic toxicity is not an issue with spinals because the mass of drug injected is so much smaller.

Total spinal anaesthesia is the effect of excessive local anaesthetic within the subarachnoid space. If a dose intended for the epidural space is inadvertently delivered to the subarachnoid space, cephalad spread can cause respiratory arrest by blocking innervation of the diaphragm (C3–C5), and profound hypotension secondary to extensive sympathetic blockade.

A ‘total spinal’ can occur even when no CSF has been apparent on aspiration, and remains a possibility hours after initiation of an epidural block and following several top-ups. The risk of inadvertent subarachnoid block is not eliminated by epidural catheterisation at another interspace after the dura has been punctured, because the dural tear might still allow passage of local anaesthetic to the CSF.

In addition to local anaesthetic toxicity and total spinal anaesthesia, maternal collapse can occur as a result of:

The management of collapse in the obstetric patient is detailed in Box 9.3.

Box 9.3 Collapse in the obstetric patient

All those working on a delivery suite should make sure they know where the resuscitation equipment and emergency drugs are kept, and keep up to date with the latest international algorithms.

Establishing regional analgesia – practical points

Table 9.3 Distinction between CSF and saline

| CSF | Saline | |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Warm | Cold |

| Protein | Present | Absent |

| Glucose | At least a trace | Absent |

| pH | 7.5 | <7.5 |

Box 9.4 Drug regimen for epidural analgesia

Either bupivacaine or levobupivacaine can be used.

Initial dose

Fentanyl 50 μg + (levo)bupivacaine 0.25% 10 ml given in two divided doses 5 minutes apart.

Initial management of dural tap

Epidural blood patch

Pudendal block

This somatic nerve block provides anaesthesia for episiotomy/perineal repair and low forceps delivery. Both pudendal nerves are blocked as they pass under and slightly posterior to the ischial spines (see Chapter 11). Use of lidocaine 0.5% allows injection of a generous total volume (up to 40 ml). If epidural analgesia has been established during labour, pudendal block will be unnecessary. A top-up of (levo)bupivacaine 0.5% with the woman sitting (in order that the local anaesthetic might bathe the sacral nerve roots) will provide excellent anaesthesia.

ANAESTHESIA FOR CAESAREAN SECTION

Pre-operative preparation

Protracted deprivation of food and oral fluid should be avoided. Elective cases should no longer be instructed to be ‘nil by mouth’ from midnight. An appropriate fasting policy is:

Women scheduled for elective caesarean section should receive the following antacid prophylaxis because of the tiny risk of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in the course of general anaesthesia after failed regional block (and the remote possibility of high spinal anaesthesia causing inability to protect the airway):

Results of a recent FBC and blood group/antibody screen should be available. A haemoglobin concentration of 80–100 g/l (8–10 g/dl) should not usually be an indication for pre-operative transfusion, but a check should be made that serum has been saved by the laboratory in case a cross-match becomes necessary. Urea and electrolytes are requested only if specifically indicated.

Non-elective cases

Causes of maternal mortality directly attributed to anaesthesia are listed in Box 9.5.

Spinal anaesthesia

Spinal anaesthesia has become the most common technique for elective caesarean section, on account of its speed and efficacy compared with epidural anaesthesia. Placental blood flow is maintained provided that hypotension is avoided. The possibility of having to resort to general anaesthesia should always be mentioned, and the airway evaluated pre-operatively.

Only rarely should pressure of time preclude institution of a spinal block for a woman who has been labouring without epidural analgesia.

Establishing spinal anaesthesia – practical points

Box 9.6 Contraindications to diclofenac

Epidural anaesthesia

This is most often used when epidural analgesia has been established during labour. There are very few occasions when a woman with a working epidural in labour should need general anaesthesia for caesarean section on the grounds of lack of available time to establish surgical anaesthesia.

Epidural anaesthesia is indicated in certain clinical conditions (e.g. congenital heart disease) when a regional technique is preferable to general anaesthesia but spinal anaesthesia is relatively contraindicated because of its potential for sudden sympathetic blockade.

Epidural anaesthesia might be favoured when provision of optimal postoperative analgesia by infusion of (levo)bupivacaine/fentanyl in a high-dependency area is warranted, e.g. severe pre-eclampsia.

Establishing epidural anaesthesia – practical points

Combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia

General anaesthesia

Tocolysis and oxytocics

On occasions, uterine relaxation might be requested to facilitate procedures such as delivery of a second twin.

POSTOPERATIVE ANALGESIA

PLACENTA PRAEVIA

The anaesthetist should engage in discussion with the obstetrician regarding the placental site and how much bleeding is anticipated. The risk of major haemorrhage is significantly increased if a previous section has been performed and the placenta is adherent to the myometrium (placenta accreta).

PRE-ASSESSMENT

All units should have a referral system between obstetricians and obstetric anaesthetists. Trainees providing out-of-hours cover should never be presented with complex cases ‘out of the blue’. Consider anaesthetic referral for any woman referred to a specialist physician’s clinic (e.g. cardiology).

Anaesthetists’ principal concerns are:

Criteria for referral are listed in Box 9.7.

PRE-ECLAMPSIA

Anaesthetists’ contributions include provision of analgesia, blood pressure control, intravenous fluid/blood product administration and physiological monitoring. Regional analgesia is strongly indicated to eliminate the pain and stress of labour and thus prevent further rises in blood pressure and improve uteroplacental blood flow. A regional block should not be regarded as a first-line treatment for hypertension – specific antihypertensive therapy should be administered first.

Spinal anaesthesia does not cause excessive hypotension (the hypertension of pre-eclampsia is mediated humorally, not neurally by the sympathetic nervous system). Standard IV boluses of phenylephrine or ephedrine do not cause an exaggerated hypertensive response.

General anaesthesia is indicated if there is a coagulopathy or symptoms (especially piercing headache) of impending eclampsia. Specific problems include laryngeal oedema, which might necessitate a smaller tracheal tube. Prior communication with the neonatal paediatrician is essential so that preparation can be made for antagonism of opioid or provision of ventilatory support.

The induction regimen should protect the cerebral circulation from hypertensive surges. Have a low threshold for direct arterial pressure monitoring. Attenuate the pressor response to intubation with alfentanil 10 μg/kg or remifentanil 2 μ/kg prior to rapid sequence induction.

In the presence of therapeutic serum concentrations of magnesium sulphate, use reduced doses of non-depolarising drugs for maintenance of neuromuscular block (e.g. mivacurium 0.15 mg/kg). A peripheral nerve stimulator is essential to monitor the degree of block.

Before extubation, consider specific therapy (e.g. labetalol in 10–20 mg increments) to avert a dangerous pressor response. If a swollen larynx was evident at laryngoscopy or intubation was traumatic, be extremely wary of post-extubation stridor.

ECLAMPSIA

Seizures occurring in late pregnancy and labour should be regarded as eclamptic unless proved otherwise. Alternative diagnoses include epilepsy, amniotic fluid embolism (anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy), intracranial pathology (tumours, vascular malformations, haemorrhage), water intoxication, and local anaesthetic toxicity.

Practical points

Burnstein R, Buckland R, Pickett JA. A survey of epidural analgesia for labour in the United Kingdom. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:634-640.

Carroll D, Tramèr M, McQuay H, Nye B, Moore A. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in labour pain: a systematic review. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:169-175.

Elbourne D, Wiseman RA. Types of intra-muscular opioids for maternal pain relief in labour. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 Issue 2. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

Shibli KU, Russell IF. A survey of anaesthetic techniques used for caesarean section in the UK in 1997. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2000;9:160-167.

Why mothers die. Report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2000–2002. 2004. http://www.cemach.org.uk