Immunization

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

Identify diseases of importance to dental practices for which there are vaccines.

Identify diseases of importance to dental practices for which there are vaccines.

Identify diseases of importance to dental practices for which there are no vaccines.

Identify diseases of importance to dental practices for which there are no vaccines.

Discuss the CDC list of vaccine-preventable diseases for health care workers.

Discuss the CDC list of vaccine-preventable diseases for health care workers.

Describe the vaccination processes for tetanus, influenza, and hepatitis B.

Describe the vaccination processes for tetanus, influenza, and hepatitis B.

Health care is the second-fastest growing sector of the American economy. In the United States, an estimated 12 million persons work in the health care industry. About 6.5 million persons are employed in the nation’s 6000 hospitals. However, a significant portion of health care that in the past was provided only in hospitals now occurs in offices, freestanding clinics (e.g., surgery and emergency care clinics), nursing homes, and many dental specialty offices (e.g., oral surgery, periodontics, and endodontics). Health care workers in hospitals and at off-site locations are at risk for the occupational acquisition of infectious diseases. After infection, disease could be spread to patients, co-workers, household members, and possibly to the community at large.

Ensuring that dental personnel are immune to vaccine-preventable diseases is an essential part of a successful infection control plan. Optimal use of vaccines can prevent transmission of disease and can help eliminate unnecessary work restrictions. Vaccination prevents illness and is far more cost-effective than individual case management or outbreak control.

Compliance with a vaccination scheme is known to be greater when the program is mandatory rather than voluntary. When the employer pays for the vaccinations, compliance is known to be significantly higher than if the employees must pay all or part of their immunization costs.

The types of health care provided, characteristics of the patient pool, and the age and experience of the health care workers influence the decision as to which vaccines should be included in an immunization program. In some cases, screening can help determine susceptibility to certain vaccine-preventable diseases. Hepatitis B is an example.

Dental personnel are exposed daily to a variety of communicable diseases present in their work environments. Protection is best afforded through the use of engineering and work practice controls. Also, personal protective equipment/barriers such as gloves, masks, gowns, and protective eyewear help prevent the majority of cross-infections. However, when immunization is available, it is the most effective method to reduce the chances of disease acquisition. Maintenance of immunity is an essential component of any effective infection control program. Current OSHA standards require certain immunization records to be maintained for all at-risk employees.

Unfortunately, vaccines do not exist for all diseases. Important “missing vaccines” for dentistry include immunization against hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus type 1, tuberculosis, and some forms of human herpesviruses.

To have the most effective and efficient office/clinic infection control program, personnel health elements must be an essential component. In addition, immunization, education and training, postexposure management, identification of medical conditions, work-related illnesses and work restriction, maintenance of records, data management, and confidentialityare important components.

Immunizations (including screenings and postexposure prophylaxis in some cases) must be combined with other elements to provide the best level of protection to health care workers. Occupational risk assessment and management, personnel health and safety education, and the proper handling of job-related illnesses and exposures are essential. Proper record keeping and data management help generate valuable information, which report the vaccination histories of the personnel and could aid in the investigation and analysis of job-related illnesses and injuries.

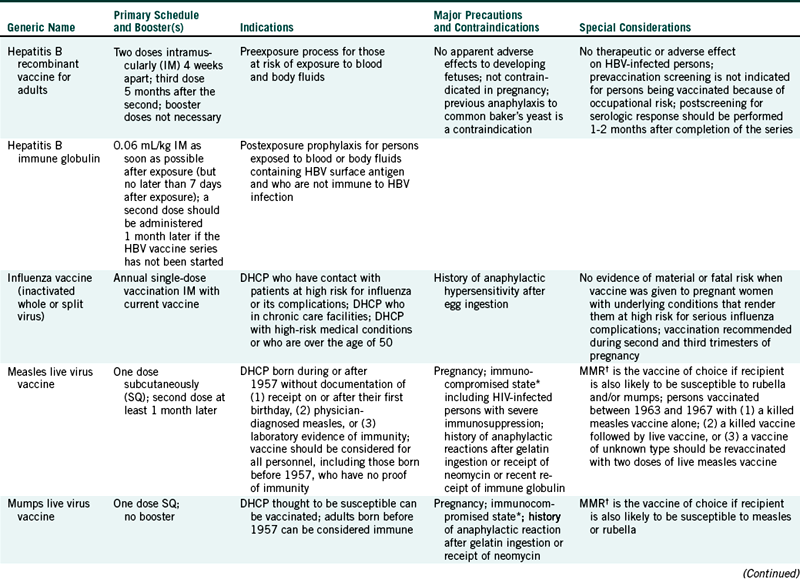

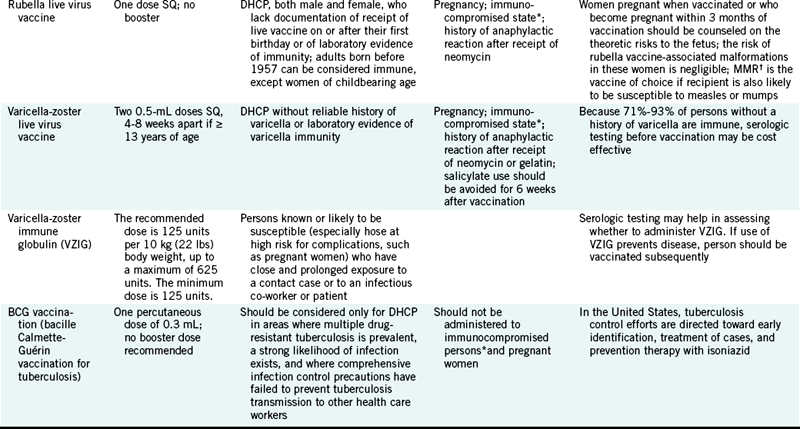

This chapter reviews tetanus, influenza, and hepatitis B in depth. Other vaccine-preventable diseases, however, are presented only for review in Table 9-1.

TABLE 9-1

Strongly Recommended Immunobiologicals and Immunization Schedules for Dental Health Care Personnel

DHCP, Dental health care personnel; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MMR, measles-mumps-rubella vaccine.

∗Persons immunocompromised because of immune deficiencies, infection with human immunodeficiency virus, leukemia, lymphoma, generalized malignancy, or immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids, alkylating drugs, antimetabolites, or radiation.

†The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that the combined measles-mumps-rubella vaccine be used when any of the individual components is indicated.

Modified from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guideline for infection control in dental health-care settings, 2003, MMWR 52(RR-17):65, 2003; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Tetanus. Retrieved May 2004 from http://www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/pink/tetanus.pdf.

TETANUS

Tetanus (“lockjaw”) is a severe disease with a high case-fatality ratio. Tetanus in the United States is primarily a disease of older adults, who usually are unvaccinated or are poorly vaccinated. Tetanus can be an infectious complication of any cut or puncture wound and is caused by the toxins (tetanospasmins) of Clostridium tetani. Proliferation of the implanted bacilli under the anaerobic conditions present in deep wounds can result in the production of the tetanospasmins.

Tetanus is usually a clinical diagnosis based on acute onset of hypertonia or painful muscular contractions (usually of the muscles of the jaw and neck first) and generalized muscle spasms. Death is often an expected outcome of infection. However, other medical problems must be ruled out first by physical and serologic examination.

Worldwide, tetanus is an important disease. In many developing countries, aseptic perinatal care and vaccination schemes are suboptimal. The result is an unacceptably high infant mortality rate. In contrast, tetanus has become rare in the United States. For example, in 1947, when reporting of tetanus started, there were 560 cases. Tetanus immunization became widely available in the mid-1940s. During the period from 1991 to 1994, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received notification of 201 cases. The impact of vaccination can be appreciated through a comparison of the 560 cases in 1947 to the 35 reported cases in 2001. Fifteen percent of the cases proved fatal.

Only two cases of neonatal tetanus have been reported in the United States during the last 20 years. Worldwide, however, an estimated 600,000 annual deaths can be attributed to neonatal tetanus. Cases involving older adults who had never been vaccinated, were vaccinated improperly, or had not received booster injections are also common worldwide.

Tetanus endospores are present in the environment continually, and because they are resistant to disinfection procedures, control of their spread requires an overt effort. Meticulous handling of all wounds and the monitoring of immune status are essential. Chemoprophylaxis against tetanus is neither practical nor useful in the management of wounds.

Tetanus is a preventable disease. Tetanus toxoid (inactivated toxin) usually is given as part of a triple childhood immunization that includes diphtheria and acellular pertussis vaccines (DTP). The initial DTP vaccine may be given as early as 6 weeks of age but always before the age of 7 years. A common regimen includes injections given at 2, 4, and 6 months. At least a 4-week interval must be allowed between each injection. A fourth dose is recommended at 15 to 18 months. The vaccine is designed to maintain protection during preschool years.

The scheme for boosters is straightforward and includes an injection when a child is 4 to 6 years old (which will protect through most of the school years). Another booster can be given when the child is 11 to 12 years old, if 5 years have elapsed since the last injection. If wounds are minor and uncontaminated, the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that boosters need be given only every 10 years. Efficacy is considered to be nearly 100%.

Routine tetanus booster immunization, usually combined with diphtheria toxoid, is recommended for all persons over the age of 7 years. Traumatic injury (large, extensive wounds exposed to soil and bacterial spores) may necessitate the earlier application of a booster. Arthus-type hypersensitivity reactions to the tetanus toxoid are known, as well as adverse effects for those in their first trimester of pregnancy and for individuals who have a history of neurologic reaction or immediate hypersensitivity.

Many wounds, especially when received during the summer (when greater numbers of viable bacilli are present in the soil), can transmit organisms more readily. However, the injured often decide not to visit a physician’s office or hospital for examination and possible treatment.

Protection against tetanus is based on the establishment and maintenance of adequate tetanus antitoxin levels and is achieved only through proper primary and routine booster injections. One should discuss the need for vaccination regularly with one’s primary health care provider.

INFLUENZA

Seasonal Influenza (the flu) is an acute respiratory disease caused by influenza type A or B virus. Incubation ranges from 1 to 4 days. Maximum viral shedding occurs 1 day before the onset of symptoms and for the first 3 days of clinical illness.

Typical features of influenza include an abrupt onset of fever, coryza, a sore throat, and a nonproductive cough. Also commonly present are systemic symptoms such as headache, muscle aches, and extreme fatigue. The flu often can be confused with the common cold (Table 9-2).

TABLE 9-2

Differences Between a Cold and the Flu

| Cold | Flu | |

| Symptoms | ||

| Onset | Protracted | Sudden |

| Fever | Rare | As high 104° F |

| Headache | Rare | Prominent |

| General aches/pains | Slight | Common, even severe |

| Fatigue/weakness | Mild | Can last 2-3 weeks |

| Extreme exhaustion | Never | Early and prominent |

| Stuffy nose | Common | Sometimes |

| Sneezing | Usual | Sometimes |

| Sore throat | Common | Sometimes |

| Chest discomfort | Mild/moderate | Common, maybe severe |

| Cough | Hacking | Common |

| Complications | Sinus congestion and earache | Bronchitis, pneumonia; can be life threatening |

| Prevention | None | Annual vaccination and antiviral medications |

| Treatment | Temporary relief of symptoms | Antiviral medications |

Unlike other common respiratory infections, influenza can cause extreme malaise for several days. More severe disease can result if viruses invade the lungs (primary viral pneumonia) or if a secondary bacterial pneumonia occurs. Complications (including hospitalization and even death) are most common among older adults and individuals with chronic health problems such as cardiopulmonary disease. Acute symptoms usually last for 2 to 4 days. However, malaise and cough may persist for up to 2 weeks.

Influenza is transmitted via aerosolized or droplet transmission from the respiratory tract of infected persons. A less important mode of transmission is by direct contact with contaminated items. Maximum communicability occurs 1 to 2 days before the onset of symptoms to 4 to 5 days thereafter. Flu season runs from November through April in the United States with a peak of activity from late December through the end of March.

Influenza causes epidemics of severe illness and life-threatening complications almost every winter. Flu epidemics affect 10% to 20% of the population and are associated with an average of 36,000 deaths and 114,000 hospitalizations in the United States. More than 90% of deaths involve persons 65 years and older. However, more than 50% of infections requiring a hospital stay involve persons under the age of 65. The economic impact of a severe epidemic in the United States could approach $15 billion.

Two measures available in the United States are capable of reducing the impact of influenza. These are immunoprophylaxis with vaccines and chemoprophylaxis or chemotherapy. Although antiviral drugs are available, chemoprophylaxis cannot be considered a substitute for vaccination.

Since the influenza viruses change frequently, new influenza vaccines are developed two times a year, one for the Northern hemisphere’s flu season (November to April) and one for the Southern hemisphere’s flu season (May to October). These trivalent vaccines consist of the three strains of influenza viruses (two type As and one type B) that are most likely to cause disease that season. There are now two types of trivalent influenza vaccines available. One is an inactivated (killed) influenza vaccine administered as a single dose intramuscularly, and the other is a live, attenuated (weakened) influenza vaccine (LAIV) administered intranasally.

Individuals at high risk for influenza complications such as persons at or over age 50, especially those in long-term care facilities or with a serious chronic disease, should be vaccinated each year. Other individuals who are clinically or subclinically infected and who live with, attend, or treat high-risk persons can transmit the virus.

The CDC recommends that all health care workers be vaccinated annually against influenza with either the inactivated influenza vaccine or LAIV. LAIV is approved for use only among nonpregnant healthy persons aged 5 years to 49 years. Health care workers who work with severely immunocompromised patients who require a protected environment should not receive LAIV. Inactivated influenza vaccine is approved for all persons older than 6 months who lack vaccine contraindications, including those with high-risk conditions. LAIV is contraindicated for:

• Persons less than 5 years or greater than 50 years old∗

• Persons with asthma, reactive airways disease, or other chronic disorders of the pulmonary or cardiovascular systems

• Persons with other underlying medical conditions, including metabolic diseases such as diabetes, renal dysfunction, and hemoglobinopathies

• Persons with known or suspected immunodeficiency diseases or who are receiving immunosuppressive therapies∗

• Children or adolescents receiving aspirin or other salicylates (because of the association of Reye syndrome with wild-type influenza infection)∗

• Persons with a history of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS)

• Pregnant women∗

• Persons who have close contact with severely immunosuppressed persons (e.g., patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplants) during those periods in which the immunosuppressed person requires care in a protective environment

• Persons with a history of hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, to any of the components of LAIV or to eggs

When properly administered, the influenza vaccine produces high levels of protective antibodies in most children and young adults. Some elderly recipients, especially those with chronic diseases (e.g., pulmonary or cardiovascular system diseases, diabetes mellitus, renal dysfunction, or immune suppression, even when caused by medication) develop lower postvaccination antibody titers and may remain susceptible to infection. However, current information indicates that 70% to 80% of healthy persons under the age of 65 are protected to the point that they will not become ill.

Since the influenza viruses used in the vaccines are grown in eggs, the vaccine should not be given to persons known to have anaphylactic hypersensitivity to eggs or some component of the vaccine without first consulting a physician. In some cases, the physician may attempt desensitization.

Annual vaccination of persons at high risk (and their close contacts) for influenza-associated complications is the most effective means of reducing the impact of influenza. Because influenza viruses undergo regular antigenic shifts, vaccination must be repeated annually. The vaccine from last year may have little to no preventive ability against the prevailing influenza viruses this year. One should discuss regularly the need and regimen for vaccination with one’s primary health care provider.

The new H1N1 virus can result in illness, doctor's visits, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States during the normally flu-free summer months and especially during the traditional seasonal winter months. Vaccines are the best way to prevent influenza. The seasonal flu vaccine is unlikely to provide protection against the H1N1 influenza. Both types of vaccines for H1N1 will be available in late 2009 - the inactivated “flu shot” injections and the live attenuated nasal spray.

The groups recommended to receive the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine include: 1) pregnant women, who are at higher risk of complications and can potentially provide protection to infants who cannot be vaccinated; 2) household contacts and caregivers of children younger than 6 months of age because younger infants are at higher risk of influenza-related complications and cannot be vaccinated; 3) healthcare and emergency medical services personnel because infections among healthcare workers have been reported, and this can be a potential source of infection for vulnerable patients plus increased absenteeism in this population could reduce healthcare system capacity; 4) children from 6 months through 18 years of age because cases of 2009 H1N1 influenza have been seen in children who are in close contact with one another in school and daycare settings, which increases the likelihood of disease spread, 5) young adults 19 through 24 years of age because many cases of 2009 H1N1 influenza have been seen in these healthy young adults and they often live, work, and study in close proximity and are a frequently mobile population; and 6) persons aged 25 through 64 years who have health conditions associated with higher risk of medical complications from influenza.

HEPATITIS B

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an infectious agent associated with acute and chronic inflammation of the liver. Worldwide, HBV is a major cause of necrotizing vasculitis, cirrhosis, and primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatis B virus can be found primarily in blood and blood products but also can be present in other body fluids, such as semen, tears, feces, urine, vaginal secretions, and saliva.

As discussed in Chapter 6, hepatitis B virus is a blood-borne pathogen transmitted by percutaneous or mucosal exposure (e.g., intravenous drug abuse and needlestick accidents by health care workers), by sexual contact, and from mother to fetus or infant. Hepatitis B virus is environmentally stable, especially when surrounded by blood. This stability allows for the potential of indirect transmission such as contact with contaminated instruments.

Hepatitis B is one of the most frequently reported vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. Each year between 15,000 and 20,000 cases of acute hepatitis B are reported. However, many persons with acute infections are asymptomatic, and many cases of symptomatic disease are not reported. Only 30% to 50% of cases have clinical symptoms indicating infection.

The CDC estimates that about 1000 health care workers occupationally acquired hepatitis B in 1994. This represents a 90% decline since 1985. The decrease is attributable to the use of vaccine and adherence to other preventive measures (e.g., universal and standard precautions).

Chronic HBV infection is defined as the presence of HBV viral markers in serum for at least 6 months. Risk of developing chronic infection is age dependent and is greatest for infants infected at birth (90% probability). Overall, 30% to 50% of children and 4% to 10% of adults with acute infections will develop chronic infections. Chronicity increases dramatically the chances for HBV transmission, cirrhosis, delta hepatitis virus infections, and the development of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. About 1.25 million persons in the United States are estimated to be infected chronically.

Hepatitis B is a major occupational hazard for dental personnel, with attack rates among unvaccinated individuals 3 to 10 times the 4% rate present in the general population. Hepatitis B is an especially difficult problem because many dental workers have repeated intimate contact with patient body fluids and with items soiled with such fluids. Hepatitis B virus infection appears to be related more to the extent of exposure to blood than to the number or type of patients treated.

Personal protective barriers cannot eliminate all body fluid exposures, especially sharps injuries. Therefore the best protection against HBV infection is immunization. Two single antigen vaccines are available in the Unites States, Recombivax HB (Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ) and Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium). Three combination vaccines are available. One (Twinrix—GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used to vaccinate adults, and two (Comvax—Merck & Co., Inc. and Pediarix—GlaxoSmithKline) are used to vaccinate infants and young children. Twinrix contains the HBsAg and inactivated hepatitis A virus. Comvax immunizes against hepatitis B and invasive disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). Pediarix vaccinates against hepatitis B, diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus.

The most common adult vaccine regimen consists of 1.0 mL doses given at 0, 1, and 6 months (see Table 9-1). Vaccination of infants (often in the delivery hospital) is common. The goals are to vaccinate at a very young age (which usually positively influences seroconversion rates) and to attempt to prevent perinatal infection from an infected mother.

Injections of the adult hepatitis B vaccine given in the deltoid muscle have produced seroconversion rates from 95% to 97% in immunocompetent, seronegative younger adults. Lower conversion rates are noted in persons over 40 years of age, smokers, those who are overweight, and individuals who received injections in the buttocks (as low as 70% seroconversion). Recent studies indicate that genetic factors may influence seroconversion rates significantly.

All at-risk dental personnel need to be vaccinated, including clinicians, laboratory workers, and associated cleanup crews. A person such as an office receptionist may be considered as not being at risk. However, many dental offices practice multitasking because when an emergency or special patient need arises, “office workers” temporarily participate in chairside dentistry.

Unless one has some reason to suspect infection, serologic screening before vaccination is not recommended. Complete protection against HBV, however, does include postscreening for antibody (anti-HBsAg)levels. This procedure should be conducted 1 to 2 months after completion of the 3-dose vaccination series. If seroconversion occurs after vaccination, protective levels of antibodies have been shown to persist for at least 23 years. If a vaccine recipient fails to seroconvert, the person should, according to CDC, receive a second series of three injections and be retested. If no response to the second 3-dose series occurs, nonresponders should be tested for HBsAg, the presence of which would indicate a hepatitis B carrier state or current infection. One characteristic of a chronic HBV infection is a person’s inability to produce a defensive antibody response to HBV.

The need for a booster injection still is debated. The CDC currently does not recommend boosters. This recommendation, however, is based on a proper immune response to vaccination verified through serologic postscreening. The antibody levels of thousands of individuals will have to be measured for a period of years before a booster recommendation can be made. However, if an individual was vaccinated more than 5 years ago and was not evaluated serologically at that time, the best course probably would be to give a single injection and then determine the antibody titer of this person. However, one’s personal physician should be consulted first over all other recommendations.

Compliance with HBV vaccination among health care workers has not been universal. Concerns expressed include vaccine safety, cost, efficacy, pregnancy-related issues, lack of information on the vaccine, and consideration of oneself to be at low risk. Hospital studies indicate that vaccination levels improve greatly when the employer pays the cost of the series. National studies show that dentists (more than 98% have been vaccinated or have been infected) are among health care worker groups with the highest rates of vaccination. Similar levels of compliance are noted for dental hygienists, with lower vaccination rates for dental assistants.

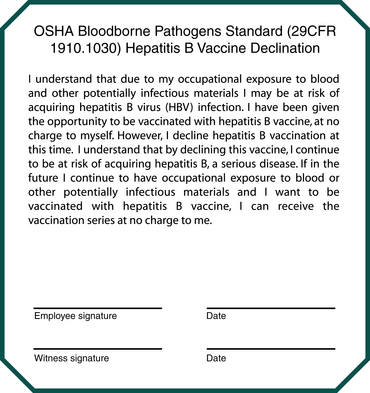

Despite the presence of a proven occupational risk and the availability of safe and effective vaccines, not all at-risk health care workers have been vaccinated. Health care workers have not been vaccinated universally for several reasons. Some still question the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. The vaccine has been shown to produce only minimal side effects. The most common complaints include transient injection site soreness and redness, headache, and fever. Individuals with severe allergies to yeast or iodine (the preservative in the vaccines) must consult their physicians before vaccination, as should individuals with pregnancy-related concerns. Another major noncompliance factor is the cost of the vaccine series ($150 to $200). The blood-borne pathogens standard of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (29 CFR 1910.1030, Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens, Final Rule, December 6, 1991) specifically recognizes the important occupational hazard that HBV presents for health care workers (see Chapter 6, Appendix H, and Box 9-1). The rule involves several employer and employee performance functions. Employers must assume all costs associated with HBV vaccination. Employees have the right to refuse vaccination. However, the employee must read and sign a declination statement. The wording must be as described in the standard. Figure 9-1 is a copy of the necessary statement.

RISK OF MISSING AN IMPORTANT OPPORTUNITY

Immunization programs have been successful in preventing diseases among children. However, most of us are not aware of the continuing need for vaccinations during adulthood. An important number of vaccine-preventable diseases occur today in the adult population. Anyone who passes through childhood without immunization or infection is at risk. Many diseases are considerably more severe when contracted as an adult. The occupations or social behaviors of adults also increase the chances of disease acquisition.

In addition to immunization against influenza, tetanus, and hepatitis B, dental personnel should discuss with their primary health care providers their immune status to other vaccine-preventable diseases. These diseases include hepatitis A, pneumococcal pneumonia, measles, rubella, mumps, and poliomyelitis. Also, whenever possible, dental personnel should make themselves available for disease screenings. Persons are screened regularly for cholesterol and blood sugar levels, blood pressure, the presence of blood in feces, and heart rate. Screenings for infectious diseases also exist. Some screenings are serologic, for example, antibody testing for hepatitis B and C, the human immunodeficiency virus, and herpesviruses. Other screenings include external monitoring for pathogen exposure; the most important of these is an annual interdermal Mantoux tuberculin skin test.

American Dental Association. Council on Scientific Affairs and Council on Dental Practice: Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:672–680.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices: Recommended adult immunization schedule—Unites States, October 2007-September 2008. MMWR. 2007;56(41):1–4.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for infection control in dental health-care settings, 2003, I. 2003;52(RR-17):1–68.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Hepatitis B vaccine: fact sheet. Accessed May 2008 at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/b/vaxfact.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Influenza vaccination of health-care personnel. Accessed May 2008 at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5502a1.htm#top.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Tetanus. Retrieved September 2003 from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/tetanus.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Viral hepatitis. Retrieved September 2003 from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/index.htm.

Cottone, J.A., Puttaiah, R. Hepatitis virus infection: current status in dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 1996;40(2):293–307.

Miller, C.H., Palenik, C.J. Sterilization, disinfection and asepsis in dentistry. In: Block S., ed. Sterilization, disinfection, preservation and sanitation. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1049–1068.

Occupational Health and Safety Administration. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens, final rule. 29 CFR 1910.1030, Fed Regist. 1991;56:64175–64182.

Review Questions

______1. A preventive vaccine is available in the U.S. against:

______2. Usually, adults need to receive the tetanus vaccine every ______________ years.

______3. The influenza vaccine is given:

______4. In what month should health care workers receive the influenza vaccine?

______5. The costs associated with hepatitis B vaccination of at-risk employees are:

a. the responsibility of the employees themselves

b. to be paid for by the employer

c. usually covered by a grant from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration

______6. Which of the following is a killed or attenuated viral vaccine?