Boundary Setting in Naturalistic Designs

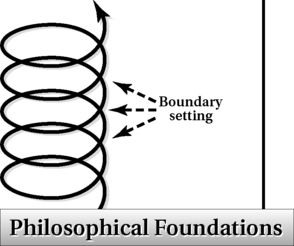

Let us now look at the way in which a researcher engages in the action process of setting boundaries when conducting a study using naturalistic designs. In naturalistic research, setting boundaries is a dynamic, inductive process. It is an action process that is flexible and fluid and that occurs over a prolonged period of engagement in fieldwork.

Because the basic purpose of naturalistic research is exploration, understanding, description, and explanation, the researcher does not often know the specific boundaries of the inquiry or the particular conceptual domains before undertaking the study. Indeed, the very point of the study may be to uncover and establish the specific characteristics that bound or define a group of persons or explicate a particular concept or human experience. Thus, for most naturalistic designs, boundary setting is embedded in the field experience; boundaries emerge and are set on the basis of the process of collecting information and ongoing formative analyses. The final determination of boundaries for a particular concept, or set of constructs, may not actually occur until the formal analysis and reporting phases of the study. Nevertheless, a researcher must start setting boundaries at some point and make decisions as to what to observe, with whom to talk, and how to proceed in the field. Thus, boundary setting in naturalistic inquiry begins broadly and then becomes refined as the research proceeds.

Ways of setting boundaries

Researchers working in the traditions of naturalistic inquiry must consider bounding their study along a number of dimensions. These dimensions include the location or physical or virtual setting, the cultural groups, the range and nature of experiences that will be examined, the particular concepts that will be explored, the artifacts that will be examined, and the ways in which individuals are involved.

Geographic Location

Naturalistic studies can investigate a wide range of locations, from virtual settings (e.g., Second Life, Internet chat rooms, blogs, Web sites) to geographic locations and physical settings. Regardless of the setting, there are basic principles for creating boundaries. Consider the following example of bounding a naturalistic study.

In this classic study, Tally’s Corner, the geographic location initially formed the boundary because the query sought to understand the lives and experiences of African American men who frequented urban street corners. The identification of a specific locale, geographic region, or area is a customary way of initially bounding a study in the naturalistic traditions. It allows the investigator to enter the field, but the location is only an entry point and may be expanded, as in Liebow’s research, to other locales as well.

Choosing the initial boundary or location is a conscious methodological decision, and the investigator may choose to then expand or not expand the location. Consider the following example, in which the location remained very bounded throughout the study.

Now we apply the principles from these examples to a virtual location.

You therefore choose your initial point of entry into the field as the interactive chat room on the Web site, setting this virtual location as your initial boundary.

Cultural Groups

Cultural groups are another way in which researchers in the naturalistic tradition may form their study’s initial boundary and point of entry. A “culture” may be loosely defined as the customs and tacit knowledge held by individuals who belong to a group. A group can be defined by ethnicity, race, or shared experience (e.g., parents of children with chronic illness, substance abusers). Culture may also be identified by the location in which it exists or as the rules, beliefs, and values that guide a person or group of people through a particular experience, such as the “culture of home care therapists,” “culture of disability,” or “culture of caregiving.”

As a researcher collects information about a cultural group, he or she may refine the boundaries of the study to obtain a fuller understanding of the group. In the previous example, you could decide to travel to Cuba to understand the cultural underpinnings and historical forces that have shaped your Cuban American study group. A researcher also might use virtual sites to expand cultural boundaries, such as Web sites devoted to a particular cultural group.

Personal Experience

In studies that focus on the exploration of a particular experience, the phenomenon immediately sets the boundaries for what will be examined; that is, the boundaries of the inquiry lie within the realm of the particular experiences described by the individuals. Experiences such as suffering, healing, aging, poverty, a rite of passages, and terminal illness are examples of potential areas of exploration from a phenomenological perspective. In phenomenological studies, the goal is to understand the experiences of a small set of individuals from their own perspectives or “lived” experience. For example, a phenomenologist who wants to describe the experience of a parent who has a child with a terminal illness may choose to interview and observe that parent. The boundary of the study (and thus the understanding derived from it) applies only to the individual’s lived experience. As stated earlier, however, the researcher must begin somewhere and make a selection decision as to which individual or individuals to interview who possess the specific characteristic of having a terminally ill child. The selection process may be purposeful in that the researcher makes the judgment as to which parent may be a reasonable “informant” given the scope or depth of his or her particular experience. Other decisions about how to delimit the study must be made as well. The researcher must decide what other data materials to examine (e.g., parent’s diaries, e-mails, favorite book, or music selection).

Similarly, suppose you are interested in the following experience.

The investigator must initially establish the immediate study purpose and bound the personal experience that is to be targeted, at least initially, to engage in a feasible research process.

Concepts

As in the previous example, some forms of inquiry explore a particular concept. Thus, it is the particular concept that initially bounds the scope of the study in these types of inquiry. Wiseman’s study3 was limited to the exploration of one concept—loneliness. The study expanded understanding of the dimensions and nature of loneliness by identifying the range of different meanings.

In other types of naturalistic inquiry, the investigator “casts a wide net” and is interested in understanding underlying values or beliefs that guide behaviors.4 In these forms of inquiry, the concepts of interest may not be immediately identified and may emerge only in the course of the study as a consequence of the analytical process.

Some studies, however, begin by setting conceptual boundaries.

The following example further illustrates the process of setting conceptual boundaries in naturalistic research. In his study of the culture of a nursing home, Savishinsky7 was originally interested in describing the behavioral responses of nursing home residents to pet therapy. He stated:

The approach that I took began with two concepts at the very heart of pet therapy—companionship and domesticity. In the broadest terms, I came to realize that the study had to be a cultural and not just a behavioral one. … It had to look at meanings and not simply actions.7

As you can see, the initial boundaries of the study—observing actions during pet therapy—became modified and expanded as the study proceeded to the nursing home culture as a whole, including not only behavioral patterns but also meanings embedded within that culture.

Involving research participants

Involving research participants is perhaps the most critical approach to boundary setting in naturalistic inquiry. It is often believed that researchers who engage in naturalistic inquiry simply select any individual on the basis of convenience or the individual’s availability for study participation. This belief is a misconception and a rather simplistic understanding of the actions undertaken by researchers to involve participants. There is nothing haphazard about selecting participants in naturalistic inquiry. The use of a convenience strategy is only one of many important approaches used by researchers working from these multiple traditions. Selecting individuals is a purposeful action process, and the investigator must be acutely aware of the implications of his or her selection decisions. Selection decisions stem from either the investigator’s theoretical perspective or the study’s purpose and the research query; or selection is informed by judgments or interpretations that emerge in the course of fieldwork.

There are important differences between experimental-type research and naturalistic inquiry with regard to involving humans in research. Knowing these differences provides a basis for a better understanding of the decision-making process used by naturalistic researchers. The concern in identifying subjects in experimental-type research is “representativeness,” as discussed in Chapter 13. Basically, the principle of representativeness suggests that the larger the sample size or the more subjects involved in a study, the better the chances of achieving representation of the target population and detecting group differences or patterns.

In naturalistic inquiry, however, usually the concern is with the selection of individuals who have the potential to illuminate a particular concept, experience, or cultural context. The number of participants in a study is not as important to the naturalistic investigator as the amount of exposure to participants and opportunities to explore phenomena in depth. The investigator therefore develops selection strategies that ensure richness of information and complexity of understanding. The concern is not with selecting individuals who represent a population; rather, naturalistic inquiry is typically characterized by a small number of study participants with whom the investigator has repeated exposures and multiple occasions to observe and interview. Decisions as to whom to interview or observe and when to interview in the course of the study are thus based on this principle. Although some researchers label the approaches used in naturalistic inquiry as sampling techniques, we prefer to call them “strategies for involving individuals.” Sampling techniques in experimental-type designs are based on the premise of representation of and randomization from a population in which the parameters of the population are already known and determined. Because the logic of boundary setting in naturalistic inquiry is inductive, population parameters are not known or even relevant to methodology. Therefore, using the term “sampling” in naturalistic inquiry is misleading and does not capture the intent of the decision-making process within these traditions.

The way in which individuals are selected for study participation in naturalistic designs depends on the study’s purpose and design. Individuals may be involved differently at distinct points in the fieldwork process. This variability is especially the case for large ethnographical studies or forms of naturalistic inquiry that occur over a long period and that focus on a broad domain of concern. In any case, researchers working from the traditions of naturalistic inquiry use a wide range of strategies for involving participants, and these strategies emerge within the context of carrying out fieldwork. Occasionally, probability or nonprobability sampling techniques may be integrated into naturalistic studies when these approaches are appropriate and fit the structure of the study’s purpose and design. These types of strategies have typically been used in large ethnographical studies and after the investigator has identified particular patterns that warrant further explication through the use of these sampling approaches. The ethnographer can use these sampling techniques to determine the representativeness of the particular concept or domain of concern within the cultural group, community, or context. When sampling methods are used in naturalistic designs, we take the position that the design moves to the category of “mixed methods.”

Patton8 and others9–11 have suggested many distinct strategies that can be used separately or in combination for involving individuals in naturalistic inquiry. The following six strategies are commonly used to identify informants. (Some of these strategies are discussed in Chapter 13 and involve nonprobability methods, such as convenience, purposive, and snowball sampling.) A researcher may begin with one strategy, such as identifying individuals to maximize variation, and then switch to another strategy, such as identifying a disconfirming case to challenge emerging interpretations.

Maximum Variation

Maximum variation is a strategy that involves seeking individuals for study participation who are extremely different along dimensions that are the focus of the study. That is, in using this strategy, the researcher attempts to maximize variation among the broadest range of experiences, information, and perspectives of study participants. Maximizing differences and variability challenges the researcher and attempts to involve a universe of experiences. From the different experiences that are unveiled, the researcher attempts to identify common patterns that cut across variations, as well as to determine the study’s boundaries. The challenge for researchers using this approach is uncovering the universe of variations.

Homogeneous Selection

In contrast to maximum variation, homogeneous selection involves choosing individuals with similar experiences. This approach reduces variation and thereby simplifies the number of experiences, characteristics, and conceptual domains that are represented among study participants. This approach is particularly useful in focus group methodology or when group interview techniques are used.

It is important to note that the selection of a homogeneous group does not mean that everyone in that group will express and interpret the experience similarly. The researcher usually discovers wide variation and diversity in expression and interpretation of an identified experience, even among a group initially selected for similarities. DePoy and Gilson12 referred to this phenomenon as “diversity patina.” That is, grouping people by characteristics that are obvious, such as race, class, gender, disability status, and age, may reveal some differences among groups but barely scratch the surface of the diversity within these groups. Thus, homogeneous selection provides an approach by which to uncover diversity within a particular group of individuals initially selected for their similar characteristic(s), or to uncover what DePoy and Gilson refer to as “diversity depth.”

Theory-Based Selection

Theory-based selection involves choosing individuals who exemplify a particular theoretical construct for the purposes of expanding an understanding of the theory. Wiseman’s study3 is an example of a theoretical approach to participant involvement. The individuals selected for this study were those who demonstrated the state of loneliness. Through in-depth interviewing using a phenomenological approach, the investigator was able to elucidate the properties of the theoretical construct. In other words, participants were purposely selected on the basis of a set of experiences that would contribute to a more in-depth examination of the construct “loneliness.”

One way the investigator could expand on this study would be to introduce a second phase of data collection. In this second phase, the investigator could purposively select individuals who did not experience loneliness. This technique would be an example of using disconfirming cases to elucidate the phenomenon under study, as discussed next.

Confirming and Disconfirming Cases

Confirming cases and disconfirming cases are strategies in which the investigator purposively searches for an informant who will either support or challenge an emerging interpretation or theory posited by the investigator. Using disconfirming cases allows the investigator to expand or revise an initial understanding of the phenomena under study by identifying exceptions or deviations. Using data from sources who may provide alternative views and experiences engages the investigator in a process of elaborating and expanding on an understanding that accounts for a fuller range of diverse phenomena than what would have been revealed without this purposive strategy. On the basis of this expanded understanding, concepts, theories, or interpretations are rethought and developed.

Extreme or Deviant Case

In the extreme case, or deviant case, the researcher selects a case that represents an extreme example of the phenomenon of interest.

Typical Case

In contrast to the deviant case, an investigator may choose to select a typical case. A typical case is one that typifies a phenomenon or represents the average.

How Many Study Participants?

There are no specific rules in naturalistic inquiry to assist the researcher in selecting the number of persons needed for interviewing or observation in a study. No procedure for naturalistic inquiry is comparable to a “power analysis” for experimental-type research. Can you guess the reasons for this based on your knowledge thus far of the naturalistic tradition?

Remember that the concern in naturalistic inquiry is not with the number of individuals who are enrolled in a study but rather with the types of opportunities and extent of exposure for in-depth observation and interviewing. Some guidelines, however, can be used to determine the number of participants to include in a naturalistic study. If the intent is to examine an experience that has been shared by individuals, a homogeneous strategy should be used to obtain study participants. Given that the naturalistic researcher is minimizing variation, only a small number of individuals (e.g., 5 to 10) will be necessary to include in the study. The small number of participants provides a “representative picture” of the phenomenon or focus of the study. In contrast, if the intent is to examine approaches to family caregiving of patients with dementia and to develop a theoretical understanding of caregiver management techniques, the naturalistic researcher may want to maximize variation in experiences and approaches to derive the broadest understanding of this activity. Thus, a larger number of caregivers (e.g., 50 to 100 individuals) from diverse backgrounds may be required, each representing different life circumstances and stages of caregiving.

Note that in naturalistic inquiry the term “representation” does not refer to or imply external validity as used by experimental researchers to mean the generalizability of knowledge or its application to others. Rather, it refers to developing a comprehensive understanding of what may be typical of or common to a group, shared experience, or virtual or geographic location.

Process of setting boundaries and selecting informants

The process of boundary setting in naturalistic research follows several principles (Box 14-1).

Boundary setting begins with the investigator determining an entry point into the inquiry. The actual point of entry into the study is often referred to as gaining access.13 Frequently, an investigator will seek introduction to a group through one of its members. This member acts as a facilitator, or a bridge between the life of the group and the investigator. From that entry point, which could be (but is not limited to) establishing rapport with other group members, examining a concept, or observing a location in which a culture lives, communicates, and performs, the researcher collects information or data to describe the boundaries.

After a researcher has gained initial access, other issues of access emerge. For example, although the researcher may be initially accepted into a cultural group or community, it may take a prolonged period before participants will share intimate information. Thus, gaining access refers not only to entering the physical or virtual location where the researcher plans to conduct extensive fieldwork but also gaining entry to the level of information and personal experiences that frame the study’s purpose.

Gaining access is not an easy action process. Much literature has been written on this important research action. The approach to gaining entry will differ depending on the context and whether the investigator is a member or stranger of the context. (Some of these issues are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 17.)

In the process of discovery and within the context of the field, the naturalistic researcher continually makes boundary decisions as to whom to interview, what to observe, and what to read. There may be an overwhelming number of observational points and potential individuals to interview. Selection decisions are based on the specific questions the researcher poses throughout the research process and the practicalities of the field, such as who is available or willing to be interviewed or observed.

Boundary setting in naturalistic inquiry begins inductively, and as concepts emerge and theory development proceeds, the researcher assumes a more deductive way of selecting observations, individuals, or artifacts to observe and the types of questions or probes to ask. For example, observational points may be chosen to ensure representation of what the researcher observes.

Throughout fieldwork, the researcher is actively determining which sources will be most helpful to gain an understanding of the particular question and to derive a complete perspective of the culture, practices, or experiences of the group or single individual. Thus, once in the field, the investigator uses other techniques and approaches to establish the boundaries of the study. For example, to understand certain practices, an ethnographer may seek a key actor or informant to represent the group. This individual is selected because of his or her strategic position in the group or because the person may be more expressive or able to articulate what the researcher is interested in knowing.

One could ask whether the same interpretive framework would have emerged had other individuals been selected and whether Liebow carefully explicated his reason for relying on these four key individuals.

As noted earlier, one strategy in ethnography is to begin broadly. The investigator initially “samples” what is immediately accessible or in view. As fieldwork and interviewing proceed, questions and observational points become increasingly focused and narrowed. The investigator may use a “snowball” or “chain” approach to identify informants, search for extreme or deviant cases, or purposely sample diverse individuals or situations to increase variation.

The process of selecting and adding pieces of information through interview, observation, and review of literature and artifacts, as well as analyzing the data for discovery and description of the boundaries of the phenomenon being examined, is called domain analysis.4 Understanding the domain, or area within the boundaries of a study, is critical in naturalistic inquiry. The intent is to understand, in depth, specific occurrences within the domain of the study. The domain must be clearly understood to ensure that findings or interpretations are meaningful. Although no claim is made about the “representativeness” of a domain in naturalistic inquiry, principles are explicated that that may be relevant to other settings. Therefore, naturalistic boundary setting is unlike boundary setting in experimental-type design, in which the purpose is to maximize representation and external validity. In naturalistic inquiry, selection processes are used to obtain a “thick description” (i.e., detailed or rich data) of a particular domain, allowing the investigator to examine the transferability of principles of one domain to another.14

Ethical considerations

There are numerous ethical considerations in making boundary decisions for naturalistic inquiry. Consider the following examples.

Other ethical issues in naturalistic inquiry involve how to enter and exit the field and how to draw appropriate boundaries between the researcher and the individuals studied. This point is particularly important as global research expands and investigators enter nations and geographies with customs that differ from their country of origin. Thus, the researcher must carefully frame the purpose and scope of the study and be clear and transparent in the relationships that are forged. Fieldwork is intense, personal, and prolonged, and researchers, once involved in a study, may have difficulty extricating themselves from the relationships forged. Also, individuals may come to expect certain favors or ways of behaving that are outside the boundary of being an investigator.

The boundaries of relationships in naturalistic research can easily become tenuous, especially in times of personal and political duress over the course of the research process.

Summary

Boundary setting in naturalistic research is an ongoing and active process. It is part of the process of doing fieldwork and emerges inductively from data collection and analysis. Research is undertaken not only to address a research problem but also to promote further understanding and descriptions of the boundaries of the research. The naturalistic researcher is constantly making decisions and judgments about who should be interviewed and when and what to observe. The investigator uses a range of selection strategies in a study. The selection strategy used to choose an individual to interview, event to observe, or artifact to review is based on the specific focus of the investigator, and this focus usually emerges in the course of fieldwork. These strategies may include probability and nonprobability techniques, as well as others developed specifically for naturalistic inquiry (e.g., typical case, deviant case). Although initially a boundary may be defined globally, the investigator delimits the nature of the group, phenomenon, or concept under investigation through domain analysis, and this occurs through ongoing data collection and analysis.

References

1. Liebow, E. Tally’s corner. Boston: Little, Brown, 1967.

2. Gubrium, J. Living and dying at Murray Manor. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975.

3. Wiseman, H. The quest for connectedness: loneliness as process in the narratives of lonely university students. In: Josselson R., Lieblich A., eds. Interpreting experience: the narrative study of lives. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1995.

4. Neuman, L. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative methods, ed 7. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Allyn Bacon, 2009.

5. Gitlin, L., Luborsky, M., Schemm, R.L. Emerging concerns of older stroke patients about assistive device use. Gerontologist. 1998;3:169–180.

6. DePoy, E. Mastery in clinical occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 1990;44:415–420.

7. Savishinsky, J.S. The ends of time. New York: Bergen & Garvey, 1991.

8. Patton, M.Q. Qualitative evaluation and research methods, ed 3. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2001.

9. Creswell JW: Qualitative inquiry and Research Design: choosing among five approaches, Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage

10. Seidman, I.. Interviewing as qualitative research, New York, Teachers College Press, 2006;vol 3.

12. Depoy, E., Gilson, S.F. The human experience. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2007.

13. Spradley, J. Participant observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1980.

14. Geertz, C. The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

In Tally’s Corner, Liebow

In Tally’s Corner, Liebow