Gathering Information in Naturalistic Inquiry

Gathering information in naturalistic forms of inquiry involves a set of investigative actions that are quite divergent in purpose, approach, and process from experimental-type research. In naturalistic inquiry, knowledge emerges from and is embedded in the unique and shared understandings of human phenomena of interest.

The overall purpose of gathering information in naturalistic inquiry is to uncover multiple and diverse perspectives or underlying patterns that illuminate, describe, relate, and even predict the phenomena under study within the context in which phenomena occur. By “context,” we mean the physical, virtual, intellectual, social, economic, cultural, spiritual, and other types of environments in which human experience unfolds. Thus, different from experimental-type approaches, which also aim to predict, the processes of collecting information in naturalistic inquiry serve as discovery and revelation in a contextual field, not verification or falsification of a theory through the specification, collection, and analysis of data in a carefully controlled environment. The investigator gathers sufficient information that leads to description, discovery, understanding, interpretation, meaning, and explanation of the rich mosaic of human experiences.

As you now know, many distinct perspectives compose the rubric of naturalistic inquiry. Thus, there is wide variation in the information-gathering approaches of researchers conducting naturalistic inquiry. For example, in semiotics the focus of data collection is on discourse, symbol, and context.1 In classic ethnography, the focus of data collection may be broader than in semiotics and may include verbal exchanges, behavioral patterns, and physical objects.2

Four information-gathering principles

Although the process of gathering information differs across the types of naturalistic inquiry, four basic principles provide guidance for action: (1) the nature of involvement of the investigator; (2) the inductive, abductive process of gathering information, analyzing the information, and gathering more information; (3) the time commitment in the actual or virtual field; and (4) the use of multiple data collection strategies.

Investigator Involvement

In experimental-type research, investigators implement a set of procedures designed to remove themselves from informal or nonstandardized interactions with study participants. Naturalistic inquiry, however, is based on investigator involvement and active participation (to a greater or lesser degree) with people and other sources of information, such as artifacts, written historical documents or virtual text and image, and pictorial representations. When working directly with humans, the quality of the data collected often depends on the investigator's ability to develop trust, rapport, and mutual respect with those participating in or being studied. The level and nature of the investigator's involvement with people and other sources of information, however, depend on the specific type of naturalistic study that is pursued (Table 17-1).

TABLE 17-1

Investigator Involvement in Gathering Information from Study Participants in Naturalistic Designs

| Type of Naturalistic Inquiry | Investigator Involvement |

| Endogenous team decisions | Variable; flexible; depends on study |

| Participatory action team decisions | Variable; flexible; depends on study |

| Phenomenological | Active listener |

| Heuristic | Fully participatory |

| Life history | Active listener |

| Ethnographic | Fully participatory |

| Grounded theory | Fully participatory |

In most forms of naturalistic inquiry, but particularly in classic ethnography, life history, grounded theory, and heuristic designs—the process of eliciting stories, personal experiences, and the telling of events—is based on a strong relationship or bond that forms between the investigator and the informant. Some researchers characterize this bond as a “collaborative endeavor” or “partnership.” In these approaches to inquiry, the primary instrument for gathering trustworthy information from study participants is the investigator. As Tedlock stated (in Denzin and Lincoln):

By entering into firsthand interaction with people in their everyday lives, ethnographers can reach a better understanding of the beliefs, motivations, and behaviors of their subjects than they can by using any other method.3

The investigator as a data-gathering instrument is a logical extension of the primary contention of naturalistic inquiry. This position, shared by many forms of naturalistic inquiry, maintains that the only way to “know” about the “lived” experiences of individuals is to become intimately involved and familiar with the life situations or representations of those who experience them. The extreme of this position is found in heuristic inquiry, in which the investigator investigates his or her personal lived experience. In phenomenological research, the investigator develops rapport with study participants but engages in active listening to understand the experiences of others. In ethnography, the researcher, as the primary data-gathering instrument, strives for intimate familiarity with the people and context in the study. By engaging in an active learning process through looking, watching, listening, participating, interviewing, and reviewing materials, the investigator enters the “life world” of others and uncovers what it means to live those experiences.

In endogenous and participatory action research, the level of investigator involvement in data collection varies depending on the way in which the study team chooses to proceed. In these forms of naturalistic inquiry, the investigator tends to serve more as a facilitator of the research process and may or may not be directly involved in the various data collection strategies implemented by the team of participants.

Naturalistic forms of inquiry may employ others in the data-gathering process in addition to the primary investigators. This strategy is particularly useful in studies involving multiple field sites or when the volume of interviews is high and requires assistance from others, who may be researchers, the subjects of the inquiry, or individuals trained in the rigorous procedures that characterize the study. In these cases, the investigator and data gatherers form a team and work together to develop consensus on methods and style to ensure similarity and consistency in the use of techniques for building rapport, as well as for probing and eliciting responses. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the data, the team must also work together to share field impressions, notes, and emerging analytical categories and themes.

For example, let's say you want to conduct a study to examine the attitudes of rural residents toward law enforcement's role in substance abuse prevention in a particular geographic region of the United States. Because the geographic area of interest is vast, more than one investigator is necessary to collaborate on the project and gather data. You form a team of investigators composed of parents, health and social service professionals, and students and you all meet every 2 weeks to discuss and agree upon where to obtain interview data, how to conduct the interviews, and how to record and aggregate responses. Although each member of the investigative team has a particular style and preferred methodologies, all agree to how best to identify and approach informants, type and level of probing questions and initial analytic approach.

Information Collection and Analysis

In naturalistic inquiry, the act of gathering information is intimately entwined with analysis—that is, collecting data and conducting analysis reciprocally inform one another. Thus, once established in the field, the investigator evaluates the information obtained through observation, examination of artifacts and images, recorded interviews, and participation in relevant activities. These initial analytical efforts detail the “who, what, when, and where” aspects of the context, which in turn are used to further define and refine subsequent data collection efforts and directions.

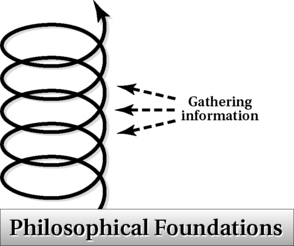

The dynamic process of ongoing data gathering, analysis, and more data gathering can be graphically represented by the “spiral” design used in this text. In the spiral, as analysis and data collection are refined, the investigator moves from a broad conception of the field to a more in-depth, richer, and “thick” understanding and, when indicated in the design, an interpretation of multiple field “realities.”4

Time Commitment in the Field

The amount of time spent immersed in a physical or virtual field setting varies greatly across the types of naturalistic inquiry. In some studies, understanding a natural or virtual setting can be time-consuming because of the complexity of the initial query and the context that is being studied. In any type of naturalistic inquiry, however, the investigator must become totally immersed in the setting or involved with the phenomenon of study. “Immersion” means that the investigator must spend sufficient time in the field to ensure that a complete description is produced. In ethnographic research, spending time “hanging out”—interviewing, observing, and participating—has traditionally been called “prolonged engagement” in the field. In ethnography, prolonged engagement is essential to ensure that the investigator reaches an in-depth understanding of the particular cultural group of focus.5 In other types of naturalistic design, engagement may be structured in diverse sequences, such as immersion on specific days and times or for specific events.

So how much time is necessary? The amount of time spent in the field may vary from specified hours each day or week to a few months to years, depending on the nature of the initial query and its scope, the availability of resources that support the investigator in the endeavor, the amount of time available to the investigator, and the specific design strategy that is followed.

Whether spending a short period or a long time in the field, the investigator must determine the point at which sufficient information has been obtained. At that point, the investigator leaves the field and engages in a final analytic or interpretive process that involves preparing one or more final reports. This point is sometimes referred to as “saturation.” Indications of saturation include the investigator no longer being puzzled or surprised by observations, events, or by what people say in the field; the investigator predicting behaviors or outcomes; and information becoming redundant compared with information already collected and learned by the investigator. When the investigator begins to hear the same story, can predict what a respondent is going to say, or can anticipate image, text, and meaning, it is time to leave the field (see later discussion on saturation).

Multiple Information-Gathering Strategies

Some methodologists suggest that by its nature, all naturalistic inquiry is multimethod.6 Because we define “multimethod” as the use of strategies from more than one research tradition, we do not see naturalistic inquiry as multimethod in itself. However, part of the naturalistic tradition is often characterized by the typical use of numerous data collection methods in a single study. Because different strategies are designed to derive information from numerous sources, the use of multiple approaches to obtain information enhances the investigator's capacity to obtain a complex and rich understanding of the phenomenon under study. It is therefore common practice to use more than one data collection strategy even if a query is small in scope. Throughout and at the end of the data collection process, all sources of information are analyzed to ensure that they support a rich descriptive or interpretive scheme and set of conclusions.

Investigators can use many data-gathering strategies, many of which are discussed later in the book In most types of naturalistic inquiry, investigators may not know before entering the field exactly which strategies they will use. Although thought and planning occur in all phases of naturalistic inquiry, the final decision to use a particular approach to collecting information occurs as the research progresses. As noted, an important part of the naturalistic process of data collection occurs during fieldwork, throughout which the investigator must decide which data collection techniques to use and at which point each should be introduced.

No standard approach is available to indicate which strategy should be used and when it should be introduced across the different forms of naturalistic inquiry. Data collection decisions are specific to the research query, the preferred way of knowing by the investigator, and the contextual opportunities that emerge while in the field. In a phenomenological study, for example, some investigators prefer to interview respondents first and then review written documents, virtual sources, journals, medical records, and other materials. In this type of study, it is considered critical initially to listen in an interview to the emotions and feelings naturally expressed by individuals asked to reflect on their experiences. Reading the literature or other textual sources before the interviewing process may introduce deductive thinking or preconceived analytical frames that may preclude attentive listening to the experiences of individuals. In contrast, some ethnographers prefer to initially “hang out” in the field and use the data collection strategy of observation before introducing interviewing or other collection strategies. Still other investigators initially conduct open-ended interviews with key informants and then engage in observation. Other strategies, such as recordings, standardized questionnaires, or review of documents or images, may be introduced at subsequent stages of fieldwork.5

Consider this example. Suppose you are interested in learning about the benefit of virtual world interaction to individuals who interact on virtual disability sites. There are numerous ways that you could enter the field. You might join and virtually hang out as an avatar, or you might immediately start a conversation with another avatar in the virtual field. Both methods would serve the purpose of gaining entry, but each would elicit a different scope of information and guide you in a different direction for further information gathering.

Overview of Principles

The hallmark of gathering information for the naturalistic researcher is that this action process is purposive and occurs in and is responsive to the context in which the investigation is taking place. Data-gathering actions are designed to examine the context and all that occurs within it. No standardized data collection procedures structure studies or set criteria for rigor. Rather, the critical components of information-gathering actions tend to be diverse, based on the particular form of inquiry and the investigator's ongoing judgments about what approaches can elicit the most relevant and illuminating data. Usually, the investigator is actively involved in the context over a prolonged time to ensure sufficient immersion in the phenomena under study. However, the level of investigator involvement varies depending on the form of inquiry. In all forms of naturalistic inquiry, best practice involves the use of multiple strategies to obtain information in an ongoing and integrated data collection and analytical process.

These basic components or guiding principles in data gathering yield descriptions, interpretations, and understandings of phenomena that are embedded in specific contexts and complex interrelationships. The complexity of phenomena is preserved in all representations and reports by the nature of the data-gathering process. Let us examine how these principles are implemented and how naturalistic inquiry actually works.

Information-gathering process

What is the process of conducting fieldwork or gathering information? Although the process has been variably defined, we have borrowed the classic and enduring structure suggested by Shaffir and Stebbins7 in the early 1990s because of its simplicity and comprehensiveness and continued relevance to the range of designs within the naturalistic tradition. Shaffir and Stebbins view the action process of data collection in naturalistic inquiry as four interrelated parts or considerations: context selection and “getting in the field,” “learning the ropes” or obtaining meanings of the setting, “maintaining relations,” and “leaving the field.”7 Although these actions appear to represent distinct phases or research steps, the process is truly integrated; each component overlaps and shapes the other.

Selecting the Context

The first decision about data collection in naturalistic research is where or in what context information should be obtained. The researcher must “bound” the study by depicting a context that is conceptual, virtual, or locational (see Chapters 12 and 14). Because naturalistic research focuses on the natural research context, as well as what happens in it, selection of a context is an important factor in gathering data. The context may be the private lives of famous people, the interrelationships of a surgical team, the world of hospice specialists, the meaning of disability to avatars in a virtual disability world, or the meanings of caregiving to immigrant families.

Context selection may sound simple, but there are several important considerations. First, the specification of a context must be practical or realistic to study. For example, how realistic is it to propose an inquiry to study the private lives of famous people? Will you be able to gain access to such individuals? Will these people choose to participate in this type of study, given that agreement will jeopardize their privacy?

Second, in bounding a study to a particular context, the researcher must be careful not to limit the focus and thus the opportunity to obtain a full picture of the phenomenon under investigation. Consider the following examples.

It is important to recognize that identifying the context of a naturalistic study will depend, in part, on the nature of the query, the design strategy, and the characteristics of the persons being studied.

Gaining Access

After the context for the research endeavor is identified, the investigator must gain access to it. This is not as simple as it may sound. Gaining access to the context of the study may require strategizing, negotiating with key individuals who may serve as gatekeepers, registering for a virtual world and even creating an avatar, and perhaps renegotiating after initial entry has occurred. In some cases, the investigator may already be a part of the natural context.

Suppose you are a student and want to understand the process of becoming a health professional following graduation. As a student in health care, you are actually an “insider” of part of particular context. Although access is not a problem in student professional socialization, access to other aspects to fieldwork may be challenging. However, even as an “insider student,” you will have to work hard to understand how your new knowledge and previous experiences influence the information you gather and interpret.

If the investigator is an “outsider,” access must be obtained. Mechanisms for gaining access have been extensively discussed in the literature, particularly by ethnographers.5,8 How the researcher gains access into a context can influence the entire course of the research process. Gaining access involves obtaining permission to enter and become part of the social or cultural setting. Investigators may use different strategies, depending on the nature of the context and their initial relationship to it. Formal introduction to an informant by another, slowly building rapport through participation, joining a club or virtual context, and gift giving are techniques used by investigators to enter a field.

Gaining access may be simple but can also take time and hard work. You need to clarify the ways you intend to be involved in the context and the implications of your study for the participants.

An important consideration in obtaining access is the degree to and the way in which the intent of your study is presented to participants (Box 17-1). The researcher must decide on the extent to which the research activity is revealed to those being observed or interviewed. Although disclosure of the purpose and scope of the research is most often made clear to those informants who provide initial access, the specifics of the research activity may remain vague to others who are either observed or interviewed at different times in the course of fieldwork. The extent of overt or covert research activities varies in any type of inquiry depending on the context, varies from study to study, and has important ethical concerns for researchers.

The other aspect of disclosure of research purpose is to ensure your informants that the information they provide will remain confidential and will be useful. Stearns discussed this issue for physicians in her classical descriptive study of how health organizations structure the professional relationship between physician and patient:

Only a few physicians refused to allow me to tape the interview. However, many expressed concerns that the interview remains confidential. This concern as well as their hesitancy to be interviewed meant that I had to be especially careful not to reveal who I had interviewed or what they had said. Confidentiality of physician (and other) responses was thus of great concern in the research.9

As Internet-based research becomes increasingly used, investigators must consider confidentiality in different ways. As mentioned, Web sites can be easily accessed without the knowledge of those who post messages or interact online. Even if you gain access by registering to become part of a listserv and remain an anonymous participant, you still must take all measures to uphold the same ethic of confidentiality that you would exercise in other environments.10

Another consideration in gaining access is the impact of the investigator on the investigated. Whether the researcher is initially an insider or outsider, his or her presence may change the nature of the field and how people present and live their experiences. The reactive effect of the investigator's presence on the phenomenon being observed is a major methodological dilemma for this type of research.

In his classic and well-known study of black men who frequented urban street corners, Liebow described the effect of his presence:

All in all, I felt I was making steady progress. There was still plenty of suspicion and mistrust, however. At least two men who hung around Carry Out—one of them the local numbers man—had seen me dozens of times in close quarters but kept their distance and I kept mine.11

“Learning the Ropes”

After initial entry into the context has been made, the investigator must gain access to different informants, personal stories and experiences, texts, images, and types of observations. Thus, gaining access remains an ongoing process that involves continued negotiation and renegotiation with members of the site or the individual or groups of individuals who are the focus of the study. This ongoing access process is part of the active work of doing fieldwork and has been referred to as “learning the ropes,”7 “obtaining meanings,” or obtaining an “intimate familiarity”12 with the setting or study phenomena. In classic ethnography, this process may appear as if the investigator is simply “hanging out.” However, a range of data-gathering strategies, including looking, watching, and listening; asking questions; recording; and examining materials, is brought into play to describe or learn meanings within a setting. These strategies are purposely chosen, combined, and integrated and are all part of the unfolding process of learning about the field.

The choice of strategy depends on the ebb and flow of the fieldwork situation and the particular issue on which the investigator is focused. Any data-gathering strategy is designed to move the investigator from being an outsider to an insider capable of understanding and experiencing the meanings of symbols, language, and behavior within the setting. The movement from outside to inside involves a reflexive process in which the investigator is constantly comparing and analyzing pieces of information. Data collection strategies are designed to reveal the unknown and examine phenomena that the investigator does not understand or finds puzzling.

This example represents what Agar referred to as a “rich point.”2 A rich point represents a problem in your understanding and is the point at which you learn that your assumptions or previous theory are not adequate to explain how things are working. Rich points reflect the active work of the investigator that bridges the distance between his or her professional, academic world and the world of the people who are the focus of the study. Learning the ropes involves using different data collection strategies that give rise to these rich points.

Information-gathering strategies

Many information-gathering strategies are used in naturalistic inquiry. The main strategies introduced in Chapter 15—observing, asking, and examining materials—have a different purpose and structure when used in naturalistic inquiry than when used in experimental-type designs.

Observing: Looking, Watching, and Listening

The process of looking, watching, and listening is often referred to as “observation.” In naturalistic research, observation occurs within the natural context or field. In this data collection strategy, the investigator can be either a passive observer of people, places, objects, and images or a participant. Passive observation involves the investigators situating themselves in the field or particular activity and simply observing what is present or absent and what occurs. In contrast, active involvement or participation in combination with observation has been classically defined as “the process in which the investigator establishes and sustains a many-sided and relatively long-term relationship with a human association in its natural setting for the purpose of developing a scientific understanding of that association.”12

More recently, Tedlock (in Denzin and Lincoln3) suggested that the process of participant observation, rather than being characterized as the intersection of scientific inquiry with investment in relationships, is a complex human interaction in which meaning and knowledge are generated by the interaction of the investigator, those investigated, and those who hear and read the research report. In participant observation, the investigator is not a passive observer but actively engages in the research context to come to know about it. The investigator begins with broad observations to describe what is seen and then narrows the focus to discover patterns and the meaning of what has been described. In descriptive observation, it is often helpful to think of the investigator as a digital still or video camera that records what it sees as it focuses or scans the boundaries of the research setting. This technique reminds the researcher that description, not interpretation, is the first step in participant observation.

Participant observation, which Tedlock renamed “observation of participation” to remind us of the need to observe ourselves in the process of the investigation, is based on the assumption that an important way of learning about a context and group of people is to participate with them in their daily activities and personally experience and observe what transpires. Participant observation has many behaviors in common with what we do in newly encountered social situations. All of us participate and observe in social situations. As an investigator engaged in participant observation, however, the researcher seeks to become explicitly aware of the way things are. The researcher remains introspective and examines the “self” in the situation and his or her experiences as both the insider participating in the event and the outsider observing the actions.

As described by Rodwell,13 “It is in the doing of data collection that the understanding of the subject of interest is achieved.”

In this classic work, Gubrium summarized the advantages of this approach as follows:

The goal is to wind up with a depiction of “the way it is,” as it were, in a particular setting. [W]e can represent the meanings of a setting in terms more relevant to our subjects than other methods permit. “I've been there,” the participant observer likes to put it, “seen what actually happens, and this is the way it is.”14

In one of his early classic ethnographies on nursing homes, Gubrium described the multiple roles he assumed over several months as a participant observer:

I took many roles, ranging from doing the rather menial work called “toileting” by people there to serving as gerontologist at staff meetings. I attempted to spend sufficient time in the setting to establish trust, to interact with as many people as possible, and to observe the varied facts of life at Murray Manor in their natural states.15

Some types of designs or fieldwork situations warrant less participation in the observation process. Nonparticipatory observation can be used to obtain an understanding of a natural context without the influence of the observer. This approach is particularly relevant to inquiry in which text, image, and other nonhuman phenomena are the focus of the study.

During the fieldwork process, looking, watching, and listening tend to move from broad, descriptive observations to a narrow focus in which the observer looks for not only more descriptive data but also specific understanding of the meanings of what he or she has observed. The degree of participation in the context and the extent of immersion vary throughout fieldwork and are based on the nature of the inquiry, access to the setting, and practical limitations.

Asking

As a method of data collection, asking in the form of interviewing is another essential strategy used in most types of naturalistic inquiry. Often, asking information from key informants is the initial and primary data collection strategy in phenomenology, ethnography, and grounded-theory approaches. The investigator may use an asking strategy to obtain an example of a social interchange to clarify or verify the accuracy of observations or to obtain the informant's experience with and view of the phenomenon under study. Asking, unlike observation, involves direct or mediated contact with persons who are capable of providing information. Thus, to collect data by asking, the researcher must establish a relationship appropriate to the level of involvement with the informant.

Asking can take many forms in naturalistic research, from an informal, open-ended conversation to a focused or long in-depth interview. Asking can occur as a one-to one interaction or in a group.16 The timing of the interview in the research process, the purpose of the asking, and the nature of the relationship with the informant or informant group all influence the type of asking the investigator chooses.

The most common form of asking in naturalistic design is unstructured, open-ended interviewing. This type of interviewing is particularly important in the beginning stages of fieldwork when the investigator is trying to become familiar with the language of the group and everyday occurrences.

The open-ended interview may consist of informal conversation recorded by the investigator; face-to-face, telephone, or online “twosomes”; or small groups in which the investigator sets the context for the interview and the informants offer their knowledge.

The ethnographic interview and life history are frequently used face-to-face interviews. In ethnographic interview, the investigator seeks to understand culture by talking with insiders in the culture under study.17 The investigator not only attends to the content of the interview but also examines the structural and symbolic elements of the social exchange between the investigator and the informant. Contemporary ethnographic interview acknowledges that meanings may be changed and may be made not only within the context of the interview itself, but also at any point from the initial communication through the consumption of the research report.3

Life history, or biography,18 is a form of naturalistic interview that chronicles an individual's life within a social context. In the case of an investigator telling all or part of his or her own life story, the term “memoir” is used to name the data source. The investigator elicits information not only on the important events or “turnings” in an individual's life, but also on the meaning of those events within the contexts in which they occur. This form of interviewing can also serve as an independent design structure.

Common forms of group questioning include focus groups and group interviews with social units, such as families with more than one individual or a cohort of individuals who share a diagnostic condition.

Focus groups are a useful methodology to explore through group discussion a particular topic, experience or phenomena of interest. Focus groups can be composed in different ways depending upon the researcher's purpose. In a focus group the investigator sets the parameters for the conversation. The participants, usually a group of 6 to 12 individuals, then address the specified topic by responding to guiding probes or questions posed by the investigator. This approach is used when it is believed that the interactions and group discussions will yield more meaningful understanding than single, independent interviews.20

Suppose you were interested in learning about adolescent attitudes toward underage alcohol use. You decide to use a focus group because it seems most feasible to elicit participation from adolescents when they are in a social group, not isolated and interacting with one another as well as the researcher.

Group interviews with small social units are also useful in observing group dynamics and symbolic meanings exchanged among group members. In cultural descriptions, questioning social units can be most valuable in understanding the structural groups of a society. This form of interviewing can also be an independent design structure.

Although the structured questionnaire is primarily used in experimental-type designs, it is occasionally incorporated into certain naturalistic inquiries. Investigators have found that structured or even semistructured questionnaires can provide important insights into specific questions that emerge in the course of conducting fieldwork. The use of a standardized instrument or structured questionnaire also enables the investigator to determine the distribution of a particular phenomenon. Consider the following example.

The use of a structured set of questions or standardized scale represents a purposeful and focused approach to asking. This approach is introduced only in naturalistic inquiry when the investigator has been in the field for some time and has developed rapport and “learned the ropes.” Although some methodologist maintain that standardized instrument use can be naturalistic, we would suggest that because of its deductive nature and theory testing purpose, the introduction of structured asking techniques that can be subjected to measurement change the naturalistic design tradition to mixed method. We discuss this point later in the book.

Four Components of Asking Strategies

Although we ask questions every day, posing clear questions that beget the answers we are seeking is not an easy task. We have all been in situations in which the answers to our questions seemed to come from “left field” until we realized that our questions were not understood as we had intended. So now we turn to a more detailed discussion of asking. In naturalistic inquiry, there are four interrelated components of an asking strategy: access, description, focus, and verification.

Access

Asking begins with access. The investigator initially wants to meet and select one or more individuals who can articulate information about the people or a phenomenon that is the focus of the study. You may ask who would be willing to speak to a stranger about personal history, events, experiences, and feelings. It is important to know the reasons someone is willing to speak to you so that you have a context to understand what the person relates. Sometimes the first key informant is someone who is formally or informally designated by the cultural group to speak to an outsider. At other times, the informant may be a person who is considered a “deviant” within the cultural group or a person who has nothing to lose by “hanging out” with a stranger. In other cases, the informant may represent the person with the most knowledge, experience, or seniority in a group.

Regardless of the informant's status, the investigator initially seeks to speak to a person or persons who can orient the researcher to the context or field of inquiry. As the research progresses, the investigator may want to select specific individuals to interview who possess distinct knowledge important to the study. Consider the following examples.

Description

After access is obtained, the initial goal of asking is to describe. Description begins with asking broad questions that become more focused as trends, recurrent patterns, and themes emerge. Frequently the investigator begins the asking process with a broad probe such as, “Tell me about ….”

Focus

On the basis of emerging descriptive knowledge, the researcher's asking becomes more focused and probing. Asking questions requires intense listening, a show of respect, and great interest in each aspect of what the informant is saying. The investigator wants to ask questions that yield answers that are detailed and go into depth about the phenomena of interest. If an informant shows or articulates disinterest or boredom with the interview, the investigator knows the questions are not salient or do not focus on the aspects of the experience or phenomenon important to the interviewee.

In developing an open-ended or semistructured interview in which you want to focus on details and elicit rich description, consider the guidelines listed in Box 17-2.

Verification

As the investigator gains an understanding of the context, asking strategies serve to verify impressions and clarify details of the setting. Verification is the process of checking the accuracy of impressions with informants.

Throughout fieldwork, the interview process may occur in one session, several sessions, or many sessions. It is usually combined with one or more of the other primary data collection strategies of observation and review of existing materials. The decision about length and frequency of asking strategies depends on the nature and scope of the query, the purpose of the interviews, and the practical limitations that influence the conduct of the study.

Examining Materials

Examining source materials and images such as texts (records, diaries, journals, e-mails, articles, narratives, letters) and images (photographs, logos, signs, spaces, architectures, and so forth) is another essential data collection strategy in contemporary naturalistic research. This is particularly the case in health and human service research, in which textual records and images (e.g., charts, progress notes, minutes, X-rays, pictures, brand identities) are routinely maintained as a natural part of the context.

Similar to looking, watching, listening, and asking, review of materials usually begins with a broad examination of items and images. Then the investigator moves to a more focused evaluation to explore recurring themes and emerging patterns. Knowledge about which materials are available may occur at any point in the process. For the most part, to access text documents that divulge personal information, the investigator should obtain appropriate consent, even if he or she is an insider. Exceptions to this principle include unobtrusive data collection in which identity of the individuals studied will not be revealed and cases when consent may not be desirable or possible. The primary aim of unobtrusively collecting information will be to keep the research role covert, with the ethical boundaries of protection of human subjects.

Recording information

While in the field, an investigator can use several strategies to record the information that is obtained by looking, watching, and listening; asking; or reviewing materials. Recording information is an important aspect of collecting information. The record of information serves as a data set that is analyzed by the investigator in the process of doing fieldwork and then more formally after leaving the field. An investigator must decide how he or she will record information while watching and listening, asking, and reviewing material. Usually, multiple recording strategies are used in fieldwork. The decision about which strategy to use is based on the purpose of the study and the resources of the investigator. Let us examine three primary mechanisms for recording information.

Field Notes

Field notes are a basic way in which investigators record information. This type of recording has been a popular topic in the research literature on naturalistic inquiry and has been described in many ways. Usually, field notes have two basic components: (1) recordings of events, observations, and occurrences and (2) recordings of the investigator's own impressions of events, personal feelings, hunches, and expectations. Some investigators separate these two components. They maintain one set of field notes that carefully document major field activities and events. In a separate notebook or computer file, they keep a running account or personal diary of their own feelings and personal dilemmas encountered in the field.

Numerous formats are suggested in the literature for recording descriptive field notes. According to Spradley,21 a matrix design can be used to examine the interaction of persons, places, and objects. Other formats are equally useful. Lofland and Lofland12 suggested recording description and bracketing impressions and interpretation within the context of the description. We have found it useful to use a laptop computer, smartphone, or other handheld device with software that allows for the screen to be divided into two longitudinal columns either through the creation of a table or by using a template. The left side is used to describe, and the right side is used to record the investigator's immediate thoughts, impressions, hunches, and questions as the observation or interview occurs. The ability to separate a description from an interpretation is important to clarify and distinguish among observation, impression, one's emotive responses to the context of inquiry and what occurs within it, and thoughts and queries to guide future inquiry.

When to record field notes has also been discussed in the literature. This decision is an important consideration in doing fieldwork and will depend on the nature of the inquiry. Some investigators find it useful to keep a pencil and pad or electronic device available at all times during participant observation activities.

Other investigators find any act of recording while participating in an event too intrusive and recommend documenting at the conclusion of the day and in privacy. Waiting until the end of the day, however, carries the risk of depending on long-term memory and losing details that may later prove to be important.

Field notes are only one way to record information and are used in conjunction with other mechanisms.

Voice Recording

Voice recording is a fundamental data-recording strategy in naturalistic inquiry primarily used when conducting on-site or virtual interviews. To capture and retain communication as precisely as possible, it is especially important to use voice recording when conducting an open-ended interview. In such interviews, informants provide long, detailed accounts that are usually difficult for the investigator to write verbatim. Naturalistic investigators use two primary technologies to record sound: audiotape and digital recording.

Audio recording requires the use of a microphone, and digital or computer-embedded memory. When using an audio recording, remember to test the equipment before an interview to make certain that it will adequately record both your voice and that of the respondent. We have learned from experience that once you lose an interview, it cannot be recreated from memory. You should plan to have a backup memory source and recorder in case there is equipment failure during the interview. You must plan for every contingency to avoid the risk of losing data.

Many researchers find digital recording extremely valuable and time efficient. Various types of recording equipment can be used, including cellular and smartphones and handheld devices that both record and digitally store information. Remember, digital recording glitches can occur, so make sure that you back up your data. After you record an interview, your next step is to label the data and backup files carefully. Of course, make sure that you use equipment and software that is compatible with your computer platform and that can be downloaded for analysis and storage with ease. If using digital recording that cannot be automatically translated to text, you will need to transcribe the recording. If you do have a voice-to-text program, make sure that the format for translation is compatible with your digital software and provides you with a useful and well-structured transcript.

Transcription is an important step that involves translating the entire recording to text, usually in a word-processing file. In transcribing, you will need to decide whether every utterance should be recorded, such as “uh hum” or laughter. You will need to decide how pauses and silences will be noted in the transcript. Voice-to-text technology is still being developed and is not perfected yet, so if you make a determination that all utterances and silences are important, you might want to type a transcript from the voice recording rather than use a computer program to create a text data file.

Typing a transcript takes time but usually is worth the effort, and it is essential when you are searching for nuances of meaning beyond actual words. Every hour of dense interview can take 6 to 8 hours of transcribing. After transcribing a voice recording, you need to compare the written record with the recording to ensure accuracy. Finally, you will want to listen to the voice recording to examine the nuances in vocalization, as well as read the transcript to analyze the narrative.

There are several considerations in using voice recording. First, you must decide whether recording will be intrusive in your field setting and will prevent informants from expressing private thoughts. Second, when using voice recording, informants must be informed that their conversations with you are being recorded. In most cases, obtaining consent from study participants is not a problem. If you are studying issues that are highly sensitive, however, such as sexual practices of teenagers or drug use among businesspeople, concerns may be expressed by informants. You will need to explain your plan for maintaining confidentiality and decide who will have access to the voice recordings and where they will be kept. Also, it is important to inform research participants that they can request that recording cease at any point in the interview process.

The third consideration in using voice recordings is their analysis. In the beginning phases of fieldwork, some investigators find that it is important to transcribe voice to text immediately after completing an interview. Reviewing these early recordings often informs the initial development of analytical categories, subsequent data collection efforts, and type of follow-up questions that need to be pursued. As throughout all thinking and action processes in research, your study purpose is foremost in guiding your choice of voice-recording method and transcription. Practical considerations, such as cost, time, and available technological capacity, are other important factors in helping you decide how to proceed.

Imaging

Imaging, including both still photography and video, is another data-recording strategy that is being increasingly used in naturalistic inquiry. Imaging is particularly useful in studies that focus on environmental elements, interactions between individuals, and person–environment activity, as well as when observations of both nonverbal and verbal behaviors are the focus of the research study. In participant observation, the investigator is involved with both nonverbal and verbal exchanges and may have difficulty monitoring the details of actions. Video imaging enables the investigator to record such details of spaces, images, and behaviors that may not be detected at the time of the observation. With imaging, the investigator obtains a permanent record that can be viewed and reviewed multiple times.

As in voice recording, many considerations and decisions must be made when using imaging. Choice of and familiarity with the equipment and ability to manage it efficiently in the field setting are clearly important. Imaging devices range from a simple camera on your cell phone or wristwatch to complex digital video camera equipment. Purpose and practical issues will help you decide the best technology and approach.

With imaging, the issue of “reactivity” needs to be considered. Do individuals monitor their appearance and behavior because of the camera? Investigators use various strategies to reduce discomfort and reactivity. Some recommend that the camera be introduced into the field environment before recording the events that are of interest. Having a camera present but not turning it on for several occasions can reduce fear or reluctance of participants to be filmed or photographed. Using a small, unobtrusive camera can also be used to create less interference in the natural setting. Another consideration is the angle of the setting and the behaviors that are captured by the camera. The video image may capture still photos or only a set of activities that are performed in front of the lens, and thus other movements and exchanges that occur simultaneously but outside its range of vision will be lost.

As in voice recording, the investigator must carefully review each still or video image many times. Initial review of an image helps inform the investigator as to how to proceed in the field and which questions to pursue. After leaving the field, formal analysis of the video images may proceed incrementally through the action if the investigator has the appropriate equipment. The use and analysis of images can become quite complex, time-consuming, and expensive.

Imaging can be used in combination with other techniques, such as participant observation, interviewing, and voice recording.

Accuracy in collecting information

At this point, you may be asking how an investigator involved with naturalistic inquiry becomes confident that the information he or she has obtained is accurate and reflects empirically shared observations of the field. This concern has been labeled as the issue of “trustworthiness.”22 After all, the investigator wants to obtain information that correctly captures the experiences, meanings, and events of the field. How are we to know whether the final description or interpretation is not simply a fabrication of the investigator or a reflection of his or her personal biases and presuppositions? A number of techniques in naturalistic inquiry are designed to enhance the “truth value” of the investigator's data collection and initial analytical efforts.

Multiple Data Gatherers

One technique used in naturalistic inquiry is the involvement of two or more investigators in the data-gathering and analytical process. The old adage “Two heads are better than one” is also true in naturalistic inquiry. If possible, two or more investigators should observe and record their own field notes or images independently. This technique checks the accuracy of the observations; more than one pair of eyes and ears are examining and recording the same context. Careful training of both observers is essential to ensure that each observer practice skilled recording and reporting and that all investigators understand the purpose and intent of the study.

Consider an investigator who is studying the culture of a group of hospitalized adolescents. The purpose of such a study may be to determine the norms of the culture as they emerge within the boundaries of the hospital unit. Using the technique of multiple observers, two or more investigators will keep field notes and images independently of one another and will initially analyze these data separately. The investigators will then meet to compare notes and impressions and reconcile any differences through in-depth discourse about the data set. Not only are multiple observers used, but multiple analyzers ensure accurate data collection as well.

Triangulation (Crystallization)

Another technique that increases the accuracy of information gathering is called triangulation.23 To reflect the complexity of multiple approaches to obtaining information, some have suggested replacing triangulation with “crystallization.”8 To dispel the two-dimensional and linear image of a triangle, the metaphor of a crystal has become useful in depicting the multifaceted data collection methods and analysis in naturalistic inquiry.

However, because of the frequency of its current use, we refer to multiple methods of data collection with the traditional term “triangulation.” By triangulation, we mean multiple approaches that bear on the same phenomenon. For example, the use of observation with interviewing, the examination of materials, or the use of all three is characteristic of triangulation in traditional naturalistic research. More recently, quantitative measures and analytical techniques such as “content analysis” have also been introduced to provide the meaning of a phenomenon from a different angle. However, we suggest once again that the introduction of strategies based on deductive logic shift the tradition to mixed methods. In triangulating, the investigator collects information from different sources to derive and validate a particular finding. The investigator may observe an event and combine observations with textual, narrative materials to develop a comprehensive and accurate description.

Saturation

Saturation is another way in which the investigator ensures rigor in conducting a naturalistic study. Saturation refers to the point at which an investigator has obtained sufficient information from which to obtain an understanding of the phenomenon under study. As previously discussed, when the information gathered by the investigator does not provide new insights or understandings, it is a signal that saturation has been achieved. If you can guess what your respondent is going to do or say in a particular situation, you have probably obtained saturation.5 In Tally's Corner, Liebow's prolonged engagement in the field ensured that the investigator obtained a point of saturation.11

However, lengthy immersion in the field may not be practical for service provider researchers, who may have limited time and funds to support such an endeavor.

You might also use random observation as a strategy to ensure saturation. In this technique, an investigator randomly selects times throughout the investigative period to increase the likelihood of obtaining a total picture of the phenomenon of interest.

Member Checking

Member checking is a technique in which the investigator checks out his or her assumptions with one or more informants. For example, if your analysis identified that the adolescents in the shelter were in need of alternative high school settings, you might verify this with your informants by asking them whether your interpretations were accurate. This type of affirmation decreases the potential for the imposition of the investigator's bias where it does not belong. Member checking is used throughout the data collection process to confirm the truth value or accuracy of the investigator's observations and interpretations as they emerge. The informants' ability to correct the vision of their stories is critical to this technique.

Reflexivity

Dissimilar from experimental-type inquiry, the presence of investigator bias is expected and addressed through reflexivity. Reflexivity refers to the systematic process of self-examination. In reflexive analysis, the investigator examines his or her own perspective and determines how it has influenced not only what is learned but also how it is learned. Using our needs assessment example, had we conducted reflexive analysis more rigorously when we initially examined the data set, we may have identified the bias toward training that we held as health professional educators and researchers. Through reflection, investigators evaluate how understanding and knowledge are developed within the context of their own thinking processes.

In discussing the importance of reflexive analysis in their research on disability culture, Gilson and Cramer were interested in the difference in disability identity between those who had birth-based and those who had acquired diagnostic conditions. Gilson noted that he expected to find disability identity and camaraderie among all of his informants and a stronger disability identity among individuals with acquired conditions.19 However, when he did not find this phenomenon in the interview transcripts, with the exception of a college student who had been exposed to the history and current status of disability rights movements, Gilson initially thought that he and his coinvestigator did not conduct a sufficient number of interviews. However, even when they proceeded to recruit and interview more informants, the finds were consistent with the initial round of interviews. Had they engaged in reflexive analysis, they might have been able to identify their own biases and its influence on this method and findings.

A personal diary or method of noting personal feelings, moods, attitudes, and reactions to each step of the data collection process is a critical aspect of the process in naturalistic inquiry. These personal notes form the backdrop from which to understand how a particular meaning or analysis may have emerged at the data collection stage. Fetterman24 suggested that keeping a personal diary is an effective quality control mechanism.

In Gilson and Cramer's study, a diary of their views of others through their personal lenses would have been purposive and important for analysis.

Audit Trail

Another way to increase rigor is to maintain an audit trail as the researcher proceeds analytically. Some suggest leaving a path of thinking and action processes so that others can clearly follow the logic and manner in which knowledge was developed. In this approach, the investigator is responsible not only for reporting results but also for explaining how the results are obtained. By explaining the thinking and action processes of an inquiry, the investigator allows others to agree or disagree with each analytical decision and to confirm, refute, or modify interpretations. In the final report, Gilson and Cramer clearly identified not only this method but also how the thinking and action processes unfolded to yield data, impressions, and theory. In this report, they discussed their reflexive analysis as well, indicating that they entered the study with expectations that were not met.

Peer Debriefing

One technique to ensure that data analysis represents the phenomena under investigation is the use of more than one investigator as a participant in the analytical process. Throughout a coinvestigated study, researchers frequently conduct analytical actions independent of one another to determine the extent of their agreement. Synthesis of analysis and examination of areas of disagreement provide additional understanding on the research query. When only one investigator engages in a project, he or she will often ask an external analyzer to function in the capacity of a coinvestigator. In some cases, a panel of experts or advisors is used to evaluate the analytical process. This form of peer debriefing provides an opportunity for the investigator to reflect on competing interpretations offered in the peer review process, thus strengthening the legitimacy of the final interpretation. In the Gilson and Cramer's study, they recruited an external analyzer who provided important analysis, bringing them to the conclusion that disability identity was not universal but rather was a phenomenon that emerged from awareness and exposure to disability activism or scholarship in disability studies.

Summary

The main purpose of the action process of data collection in naturalistic inquiry is to obtain information that incrementally leads to the investigator's ability to reveal a story—a set of descriptive principles or understandings, hypotheses, or theories. Each piece of information is a building block that the investigator inductively collects, analyzes, and puts together to accomplish one or more of the purposes just stated. The researcher begins with a broad query that gradually narrows, like a funnel, as data collection proceeds and the context becomes clearer to the investigator.

In naturalistic research, the organization and analysis of data collection go hand in hand. Data collection and data management continue to unfold dynamically (see Chapter 18) as analysis reveals further direction for information gathering (see Chapter 20). The investigator is the main vehicle for data collection, although the researcher's involvement may vary among design strategies. To enhance the accuracy of data collection, multiple observers and triangulation of collection methods are two action processes often used by naturalistic investigators.

The naturalistic researcher uses one or more of three basic methods to gather information: observing, asking, and examining materials. Observing, consisting of looking, watching, and listening ranges on a continuum from full to no participation in the context that is being observed. Asking also varies in structure, with interviewing as the primary asking process in naturalistic design. Examination of materials occurs in an inductive way and is intended to reveal patterns related to the phenomena under study. Naturalistic data collection occurs along with analysis and moves from broad information gathering to more focused collection of information. The combination of these approaches is critical to obtain breadth and depth of analysis.

As descriptive data are collected to illuminate the answer to “what, where, and when,” the next step in the process of many naturalistic designs is to focus data collection efforts based on the ongoing analytical process. The process of information collection continues with “why and how” questions. In ethnography, this effort is called “thick” description, or focused observation, in which meanings are sought.

Focused observation hones in on examining the patterns and themes that emerge from descriptive information. The investigator may choose to examine one pattern at a time or may focus on more than one. The investigator narrows the scope of inquiry to themes and the interaction between patterns and themes while remaining open to further discovery. In general, collection strategies provide information that answers the “where, who, how, when, and why” questions. Answers to these five questions yield description, understanding of the context, occurrences within the context, and timing.

References

1. Van Leeuwen, T. Introducing social semiotics: an introductory textbook. Hoboken, NJ: Routledge, 2004.

2. Agar, M.H. The professional stranger: an informal introduction to ethnography, ed 2. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, 1996.

3. Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S. Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2005.

4. Geertz, C. Interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

5. Pole, C. Fieldwork. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2004.

6. Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C. Handbook of mixed methods social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2003.

7. Creswell, J.C. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2006.

8. Maxwell, J. Qualitative research design. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2004.

9. Stearns, C.A. Physicians in restraints: HMO gatekeepers and their perceptions of demanding patients. Qual Health Res. 1991;1:326–348.

10. Fielding, N.G., Lee, R.M., Blank, G. The handbook of online research methods. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2008.

11. Liebow, E. Tally's corner. Boston: Little, Brown, 1967.

12. Lofland, J., Lofland, L. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative research. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, 1984;18.

13. Padgett, D. Qualitative methods in social work. Thousand Oaks, Calig: Sage, 2008.

14. Gubrium, J. Recognizing and analyzing local cultures. In: Shaffir W., Stebbins R., eds. Experiencing fieldwork: an inside view of qualitative research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1991.

15. Gubrium, J. Living and dying at Murray Manor. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1975;X–XI.

16. Rubin, H., Rubin, I.S. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data, ed 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2004.

17. Spradley, J.P. The ethnographic interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1979.

18. Goodley, D., Lawthom, R., Clough, P., et al. Researching life stories. New York: Routledge, 2004.

19. Gilson, S., DePoy, E. Disability, Identity, and Cultural Diversity. Review of Disability Studies. 2004;1(1):16–23.

20. Barbour, R. Doing Focus groups. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2008.

21. Spradley, J.P. Participant observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1980.

22. Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educ Commun Technol J. 1981;29:75–92.

23. Bluebond-Langner, M. The private worlds of dying children. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978.

24. Fetterman, D.L. Ethnography step by step. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 2009.

Assume that you want to examine the initial meanings attributed to the diagnosis of breast cancer among women in their 20s. This approach represents a rather focused query that could require a few months of interviewing women in this age group who have recently learned of their diagnosis. Or you might even spend several hours in a group interview with this same group of informants, significantly reducing the time in the filed. Even if you plan to observe providers interacting with these women, your observations will be confined to this early treatment phase.

Assume that you want to examine the initial meanings attributed to the diagnosis of breast cancer among women in their 20s. This approach represents a rather focused query that could require a few months of interviewing women in this age group who have recently learned of their diagnosis. Or you might even spend several hours in a group interview with this same group of informants, significantly reducing the time in the filed. Even if you plan to observe providers interacting with these women, your observations will be confined to this early treatment phase.