Sharing Research Knowledge During and After the Study

Although you may have completed the collection and analysis of information for a study, your efforts as a researcher are not quite complete. The 10th essential of research, “sharing research knowledge,” involves two important action processes: purposeful reporting and dissemination of knowledge gained from a study. Unless you report and disseminate, you have not completed the research process. Sharing knowledge is critical to knowledge building. Also, communicating knowledge gained from an inquiry with those who can benefit is an important ethical action.

By reporting research knowledge, we mean the preparation of a communication of all or part of an inquiry to one or more audiences. Dissemination follows reporting and is defined as the action process of purposely sharing the report. These action processes usually occur at the conclusion of a research project. Often, however, there are opportunities to communicate the progress of a study or report some of the methodological challenges before completing the actions of data collection and analysis. As example, many researchers participate in conference sessions designed to provide a venue for preliminary sharing of methods and results in order to obtain feedback to improve their projects.

Think about our definition of research in Chapter 1. Do you remember the four criteria to which a study must conform? These four criteria, which apply to any type of research inquiry, are the following: logical, understandable, confirmable, and useful. Reporting and disseminating are two research action processes that also reflect these criteria. However, “usefulness” is the one research criterion that cannot be accomplished without communicating to others the findings of a completed study and their meaning.

Reports are designed to fit a particular avenue or context that is chosen for the dissemination of research findings. The methods chosen for reporting research are purposeful. They are driven by several factors, the most important of which are the question or query and the particular audience or community on whom the researcher wants to have an impact. We believe that three basic principles should inform the action process of reporting: writing guidelines, accessibility, and linguistic sensitivity.

Writing and preparation guidelines

We begin our discussion with writing and preparation. For the mostpart reporting is shared through writing. However, more recent methods have been instrumental in creating new reporting methods, such as the creation of imagery to present research findings. Mapping is an example of images that are powerful in sharing results. It is not unusual for a single inquiry to generate multiple reports in multiple formats.

Because writing remains the primary method for reporting, we discuss this format now. As you probably have surmised by now, each type of inquiry has a distinct language or set of languages, images and structures that organize the reporting action process. However, all written reporting, regardless of the research tradition that the report will reflect, is based in a common set of guidelines.1 These include issues related to clarity, purpose, knowledge of target audience, and citation style.

Clarity

Writing a report serves little purpose if it is not understood.2 Therefore, an investigator should be certain that his or her report is clear and well written. There are many books on writing and many ways to approach this task, which is often difficult, particularly for the new investigator. As in any professional activity, the more you do it, the more proficient you will be and the easier the task will become. It is important to recognize that writing is an important aspect of the research process; it takes time, thought, and creative energy.

Purpose

As we have stated throughout this book, multiple purposes drive the selection of research action processes. These purposes also structure the nature of the reporting action process.3 Consider, for example, two different purposes for writing a report: for publication in a professional journal and a written evaluation for a community organization. Researchers who write for the purpose of publishing their research in scholarly journals must conform to the style and expectations of the journal to which the manuscript is submitted. The researcher may also consider writing an article for practitioners and thus will present results and interpretations somewhat differently. The researcher who has just completed an evaluation of a community program may need to write a report to the board of directors or the funding agency to ensure continuation of financial support. In this case, the researcher may emphasize positive programmatic outcomes and write the research report consistent with the expectations of the funding agency. For the journal, a full and detailed report using the technical and professional language of the journal and readership would be warranted. However, for the agency, an executive summary with bullet points might be a better means through which to report findings. Each purpose for conducting and reporting research must be carefully considered.

Multiple Audiences

As stated earlier, being aware of the many audiences that can benefit from an inquiry is critical to meet the “useful” criterion in our definition of research. Audiences are diverse in their languages, the meanings they attribute to language, and their values regarding credibility. Thus, along with purpose, the audiences for whom the report is written will determine, in large part, how the report will be structured, what information is contained within it, how the information is presented, and the degree of specificity that will be included. The audience may vary in areas of expertise and knowledge of research methodology. The important point is to identify your reason for writing a report to a particular audience and to assess how that purpose can be communicated to that audience. You need to write in a style that is consistent with the level of understanding and knowledge of the targeted reader. As an example, suppose you have completed a participatory action research project in which individuals with intellectual disabilities functioned as researchers and informants to identify recreation needs in rural communities. Careful attention to the literacy levels of multiple audiences including those with cognitive challenges would be warranted. To this end, the concepts of accessibility and linguistic sensitivity are important, as discussed later.

Citations

You need to be aware of several other important points as you develop reports. The first is the issue of plagiarism. We realize that most researchers who plagiarize do not intend to do so. To avoid this potential and devastating mistake, you need to be aware of the norms for citation and credit. All work produced by another person, even if not directly quoted in your work, must be cited. Many different citation formats are used in health and human service research. We refer you to your publication source for the correct format and urge you to become familiar with it. If necessary, have someone else check your work to ensure that you have properly credited other authors.

Another important point to remember in report writing is that it is not an acceptable practice to excessively quote from other research studies in the literature review of an article for a journal. Many students of research like to review a body of literature by stringing together a series of quotes from different articles. However, the review of the literature section in a report must reflect a summation and critical analysis of the most salient aspects of existing studies. Quoting simply reiterates the work of others without synthesis and critical commentary.

Another common error among newcomers to formal writing is the use of citations that you have not directly read. Consider the following example.

Before we leave the section on citation, we call your attention to the wonders of technology. As we noted earlier, citation formats differ according to discipline and venue. Before the advent of electronic databases and automated formatting, one major element of report preparation was formatting the reference section and citations within the text. Now, with software programs such as Endnote and embedded bibliographic databases in word processing programs, citing and referencing is a snap. All you need to do is enter complete information about a source into fields in your database and select the format. The software does the rest by automatically locating citations in the text and formatting your reference or bibliography according to the style that you have chosen.

With these commonsense principles, let us now consider the specific writing considerations for each tradition.

Writing and presenting an experimental-type report

Reports of experimental-type research use a common language and follow a standard format and structure for presenting a study and its findings. The language used by the experimental-type researcher is “scientific” in nature. It is logical and detached from personal opinion. Interpretations are supported by numerical data. There are usually seven major sections of an experimental-type report (Box 22-1). Although investigators sometimes deviate from this order of presentation, these sections are usually considered the critical components of a scientific report. Let us examine each section.

The abstract appears before the full report and briefly summarizes or highlights the major points in each subsequent section of the report. It includes a statement of the research purpose, brief overview of method, and summary of the major findings and implications of the study. Usually the abstract does not exceed one or two paragraphs. Professional journals usually specify the length of the abstract; some journals require brief abstracts that are no longer than 100 words.

The introduction presents the problem statement, the purpose statement, and an overview of the questions that the study addresses. In this section, the researcher embeds the study in a particular body of literature and highlights the study's specific intended contribution to the disciplinary and professional knowledge and practice.

The background and significance section reviews the literature that provides the conceptual foundation for your research study. In this section, key concepts, constructs, principles, and theory of the study are critically summarized. (Refer to your literature chart or concept matrix to help organize the background and significance section.) The degree of detail in presenting the literature will depend on the researcher's purpose and intended audience. For example, in a journal article the researcher usually limits the literature review to an overview of the broad field of inquiry and then focuses on the seminal works that precede the study, whereas in a doctoral dissertation, all previous work that directly or indirectly informs the research question is detailed and critically reviewed. Some researchers combine the introduction and literature review into one section. Grinnell and Unrau3 named the combined introduction and literature review “the problem statement.”

The method section consists of several subsections, including a clear description of the design, an explication of the research question or questions, the population and sample, the measures or instrumentation, the specific data analysis strategies, and the procedures used to conduct the research. The degree of detail and specificity is again determined by the purpose and audience. However, sufficient information must be provided in each subsection of methods so that the reader has a clear understanding of how data were collected and the specific procedures that were implemented.

The analyzed data are presented in the results section. Usually, researchers begin by presenting descriptive statistics of their sample, then proceed to a presentation of inferential and associational types of statistical analysis. A rationale for statistical analysis is presented, and the findings are usually explained. However, interpretation of the data is not usually presented in this section. Data may be presented in narrative, chart, graph, or table form. You should be aware that there are prescribed formats for presenting statistical analyses. Ary et al.4 provided excellent information to guide both the preparation and the evaluation of written reports.

The discussion section may be the most creative part of the experimental-type research report. In this section the researcher discusses the implications and meanings of the findings, poses alternative explanations, relates the findings to published work contained in the literature review, suggests the potential application or use of the research results. Most researchers include a statement of the limitations of the study in this section as well, although this can also be found in the sections that discuss methods or findings.

The conclusion section is a short summary that provides interpretations and application of the study findings to future research directions or health care and human service practices.

As you can see, writing an experimental-type report follows a logical, well-accepted sequence that includes seven essential sections. The degree of detail and precision in each section depends on the purpose and audience for the report.

Also, it is important to note that there is a specific reporting structure for the true experimental design, the randomized controlled trial. Because this design strategy requires highly specified elements, such as randomization, a control group, a treatment group, and analysis and interpretation of treatment effects, the reporting follows a rather uniform presentation.

CONSORT Reporting

To enhance the scientific utility and transparency of each action process in this design strategy, efforts have been made to standardize the reporting of trials. In the 1990s, an international body of researchers engaged in clinical trials put forth the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) in an effort to provide standard language and structure and enhance the ability of readers to evaluate the validity of trials. The CONSORT includes a checklist of the items that should be included in a report of a trial and a flow diagram indicating enrollment and participation status of study subjects. It has been adopted by many medical journals, including The Lancet and the Journal of the American Medical Association, which now require written manuscript submissions that are reporting trials to use the checklist and flow diagram.5 For example, the checklist for the method section indicates the need to report the following design elements: participants, interventions, study and intervention objectives, outcome measures, sample size, randomization procedures, blinding techniques, and statistical methods.6

Preparing tables and figures

Tables and figures are important parts of experimental-type research reports. They reduce complicated data by systematically organizing important findings. Different from narrative, which tells a story, tables and figures present visuals of rankings, relationships, and significance. In experimental-type reports, tables, charts, and figures are used to present data in the results section of a report.

Tables present numeric data in rows and columns, whereas charts are displays of information that may be numeric but may also be in the form of a picture or image. Both tables and charts can be univariate (presenting data from one variable) or multivariate (presenting data depicting the relationships among two or more variables). Tables also can present related numeric information, most typically raw scores adjacent to computed values of a statistic and probability.

Among the most frequently used univariate charts are pie charts (depicting relative percentages), bar charts comparing frequencies, scatterplots, and curves (such as the bell curve) showing the distribution of scores on a variable.

With the increasing use of computer programs, figures and tables are simple to create. Even freeware has built-in automated functions that convert numeric findings from numbers into tables. Of course, we have all seen tables and figures of the same data that visually present different pictures. Care should be taken to create figures, tables, and charts that are not misleading but are designed to clarify and highlight important findings. Your narrative about these visuals should call attention to important points and trends without repeating what is contained within the visual displays.

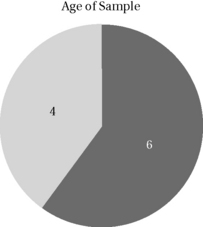

Consider the example of age. Suppose you have the following ages represented in your sample: 21, 25, 56, 67, 30, 32, 35, 65, 62, 32, and 25. What might you want to communicate about age? You could rank order the numbers from youngest to eldest for clarity, but you might want to make it easier for your readers to understand the age trends of your sample.

You might want to use a table to show the two extremes in your sample:

Or you might present these data in the form of a pie chart:

As you can see, the pie chart provides an image that tells a story in a simple but clear format.

Preparing a naturalistic report

Because of the many epistemologically and structurally different types of research designs that reflect naturalistic inquiry, there is no single, accepted format for preparing a final report. However, some basic commonalties among the varied designs can guide report writing in this tradition. Unlike experimental-type reporting, naturalistic reporting does not follow a prescribed format with clear expectations for language, nature of data, and structure. Reports tend to be rich in detail and description and draw on data in the form of narratives, images, or both to illustrate major themes and interpretations. The structure of the presentation is not standardized, and there is great variation in the format, sequencing, and nature of information7 and approach. The approach used by the researcher reflects his or her underlying interpretive scheme. Interpretive schemes are often presented as a “story” in which main themes and subtexts unfold as the story is told. Consider the following examples: in your effort to develop meaningful fitness activity for youth with intellectual impairments who reside in an urban area, you review the evidence-based practice literature and find that for your population, the recommended strategies are not productive. So you plan a naturalistic approach to reveal what activity would be meaningful and engage youth in physical activity. Through observation of the children and interviews with parents and teachers, you find that socialization during physical activity combined with a goal or increasing competition for number of city blocks walked are two strategies that produce the outcome of increasing physical activity and fitness of these youth. Different from a narrative of your observations, you develop your report as a log of the social interactions, activities, and stories told by the youth themselves.

Now consider that you have just moved from an urban to a rural border area in northern New England to develop a similar fitness program in this area. Although there is a significant body of evidence-based practice literature and you have just documented yet another successful programmatic approach, you become aware of different cultural, geographic, and place-bound factors that raise questions about the relevance of urban approaches to your population. For example, you realize that unlike the urban outdoor walking in which youth could compete on sidewalks that have easily measurable distances, walking in rural areas does not occur on sidewalks. Moreover, snow and ice for much of the year may require the use of snowshoes or other equipment. So you decide to conduct another naturalistic inquiry to support a direction and grant application for your program. Although the stories, customs, and recommendations of families and community members are powerful, you find that in this inquiry, your photographs and video images of the youth in context “tell the story” most graphically and are most compelling, particularly in the winter months when outdoor fitness is a challenge. So you seek permission to include these visuals as data, and interpret these images for the audiences reviewing the report in your analysis.

Another important aspect of reporting in naturalistic inquiry is the inclusion of a section that describes the researcher's personal biases and feelings in conducting the study. For example, in the rural study, you realize that your own distaste for being cold has shaped some of your interpretations and recommendations. Many researchers discuss their personal perspective on conducting the study as part of the introduction to their report.

Although the report in naturalistic inquiry may be structured in many ways, it contains some of the same basic elements used in report writing for experimental-type research. Using the language of naturalistic research, Box 22-2 provides the basic sections for writing a report. Reporting in naturalistic research may not follow the sections in the sequence as shown, but each report usually contains these basic elements.

The introduction in naturalistic design contains the purpose for conducting the research. An investigator may include personal purposes, as well as a purpose related to the development and advancement of professional knowledge.

The query, epistemological foundation, and theoretical framework may appear separately or combined in one section of the report. As described in previous chapters, these thinking and action processes are integrated throughout the conduct of naturalistic research and therefore can be presented as such. However, consistent with the principle of clarity in presentation, investigators need to select a format that is clear and easily understood by the target audience and consistent with the purpose of the study and report.

By now you may have noticed that we have not listed literature review as part of the reporting process. Consistent with the naturalistic research tradition, literature may be presented as a conceptual foundation for the query or as evidence that supports the data or main interpretations presented by the investigator. In most reports, the literature is used to ground the research in a body of knowledge, to support the main findings, or to examine competing interpretations of the findings.

Reporting naturalistic research departs from experimental-type reporting in the presentation of the research process and information. Naturalistic investigators rely heavily on the narrative and, increasingly, images to report their data.8 Quotations from informants may be woven throughout the narrative text. Visual and numeric display of information, such as taxonomic charts, photographs, logos, and content analyses, are also used in naturalistic reporting, depending on the query, epistemological foundation, purpose, and intended audience. Let us now consider how the reports from various naturalistic designs may be structured.

Ethnography

Although there are divergent approaches to ethnography, the primary function of this approach is to identify patterns and characterize a cultural group. Therefore, the report tells a story about the underlying values, roles, beliefs, and normative practices of the culture. It is not unusual for ethnographers to begin with “method”; that is, the investigator frequently begins by reporting how he or she gained access to the cultural setting. The report may be developed chronologically, and literature, other sources of information, and conclusions are interspersed throughout and summarized in the end. Liebow9 exemplified this classic structure in Tally's Corner.

A written report in ethnography is usually lengthy because of the expansiveness of the domain and nature of narrative data.

Phenomenology

Because the focus in phenomenological research is on the unique experience of one or more persons, the report is often narrative and written in the form of a story. Photographic images may be included to enhance the data. If specific points about the lived experience of the informants are made, they are fully supported with information from the informants themselves, frequently in the form of direct quotes from the field notes. Because the length of phenomenological studies varies extensively, they may appear as full-length journal articles, books, or other literary styles between these formats. The reports highlight life experience and its interpretation by those who experience it, and they minimize interpretations imposed by the investigator.

The nature and purpose of phenomenological designs differ from those of ethnography, as does the reporting format. In both cases, form follows function. In ethnography the function of the investigator is to make sense of what he or she has observed, whereas in a phenomenological study, the investigator reports how others make sense of their experience. These differences are clearly reflected in the written report.

In summary, naturalistic researchers use a variety of reporting action processes to share their findings. Although there is a heavy reliance on narrative data, the naturalistic investigator has the option of using numeric and visual representations, as well as other media. All reports contain the basic sections (see Box 22-2), but the order and emphasis differ among naturalistic designs and the preferences and personal styles of the investigator.8,9,11

Preparing an integrated report

Because integrated reports have made a relatively recent appearance in the research world, there are no guidelines for language and format.12 In addition, the nature and structure of the report depend on the level of integration, types of designs used, purpose of the work, and audience who will receive the report. We can, however, offer two principles that may help your reporting action process. First, you should include the components of a complete research report (see Boxes 22-1 and 22-2). Regardless of its length, organization, or complexity, your report should contain a statement of purpose, review of the literature, methodology section, presentation of findings, and conclusions. Second, because integrated design is not as well established as designs that are distinctly experimental type or naturalistic, it is often useful to include an evaluation of the methodology in the report and the justification for the use of each design, as well as the way in which each complements the other.

Accessibility

In addition to guidelines for writing and presenting, there is another important reporting principle. Communicating knowledge brings with it an important obligation, that of providing knowledge in accessible formats for all groups who may benefit. Accessible is a term that describes the usability of a product or service. In the case of communicating research, the “product” is the research report.

In the past thirty years, two approaches to expanding information access have emerged: accommodative and universal. Accommodative strategies refer to those that adapt and customize information to meet condition or group-specific needs.13 Universal approaches (often called “universal design” or “universal access”) are distinct from group-specific approaches in that they provide information in forms that all people, to the extent possible and regardless of group-specific diversity characteristics, can access without the need for adaptation.14 Vanderheiden (in Preiser and Ostrow) suggested that because of the huge range of human diversity, universal design is a “process” rather than a tangible outcome:

Universal design is more a function of keeping all of the people and all of the situations in mind and trying to create a product that is as flexible as is commercially practical.15

To the extent possible and purposive, we believe that it is incumbent on researchers to plan communication so that it can be accessed by all who can benefit. Universal approaches to communication of information provide the framework for this goal (see later discussion on dissemination).

Linguistic sensitivity

The third principle we discuss in reporting research concerns how language is used in a particular context, or linguistic sensitivity. By linguistic sensitivity we mean having knowledge about the target audience and the meaning of language to that group. Our point can be best illustrated by two recent incidents that occurred to colleagues.

In both situations, much can be learned about communication and the meaning of words, or language. The Egyptian experience illustrates that people who speak the same language do not necessarily speak the same “meaning.” The conference incident demonstrates that credibility varies between and within groups. That is to say, the language of evidence that is convincing to one group or individual may not be believable or even interesting to another. Keep these stories in mind as you plan and implement the action strategies of sharing knowledge.

As suggested throughout this book, there are multiple research languages and structures. Likewise, there are multiple ways in which you may choose to present and structure the reporting and disseminating of your research. The reporting language and structure you use must be congruent with the epistemological framework of your study; it must fit the purpose for dissemination and the target audience. In all types of communication, keep in mind the important points made earlier about diversity in meaning, differing perceptions of the criterion for credibility, and universal access. Also, remember that research reporting and disseminating are analogous to telling a story. As Richardson stated:

Whenever we write science, we are telling some kind of story, or some part of a larger narrative. Some of our stories are more complex, more densely described, and offer greater opportunities as emancipatory documents; others are more abstract, more distanced from lived experience, and reinscribe existent hegemonies.16

Dissemination

Many ways are available to you to disseminate your research. Let us examine three popular modes of disseminating.

Sharing Written Reports

Sharing a written report is one of the most common ways of disseminating research findings. As discussed, written reports may reflect different formats, depending on the purpose of the report and the audience. Journal articles may be the most popular outlet for disseminating a written report, but many other valuable formats are available. These include research briefs in periodicals and newsletters; summary articles in professional newsletters, local newspapers, and university newsletters; as well as reports to funding agencies, master's and doctoral theses, chapters in edited books, and full-length books. After you have written a report, the next action process is publication. More recently, blogs have become popular methods for sharing research. Although electronic media have made it possible to share findings almost immediately, we suggest that you use caution in evaluating the research methods as well as findings. The guidelines for evaluation of the literature that are suggested in Chapter 5 are relevant for literature in all formats and can help distinguish rigorous from less efficacious reports.

Publishing Your Work

The process of publishing your work is exciting but sometimes frustrating if you are new to the process. The first step in considering publication is to ensure that your work is high quality and meets the rigorous standards for research discussed in previous chapters. However, writing a sound report does not ensure publication. If you are attempting to publish your first piece of work, we suggest that you consult with someone who is knowledgeable about the process.

It is critical to select a medium that is compatible with the design, purpose, focus, and level of development of your work. Each publication has a set of guidelines and requirements for authors that are usually available in one or more of the yearly issues of the publication. Scholarly and professional journals usually publish instructions for authors at least twice a year or now leave them available online throughout the year. These guidelines include a list of the required format for writing, typing, notation style, image clarity and permissions, and submission processes. For refereed journals, after you submit your work, it is sent to several (usually three) reviewers for comment and evaluation. This process takes between 3 and 6 months. Do not be surprised if your work is rejected. Most journals have many more submissions than they can publish, and rejection does not mean your work is poor. It is not unusual for journal editors to suggest alternative journals that may accept your work. If your report is accepted, frequently it will be accompanied with requested revisions from the reviewers or the editor. After revisions, the work is placed in an issue, and galley proofs are sent to you for your review. These galleys are typeset models of your work. Be vigilant in reviewing them to ensure that no mistakes have occurred in the typesetting process.

Celebrate your work as you see it in publication. You have met the research criterion of “usefulness”!

Sharing Your Research Through Other Methods

Written dissemination is not the only method for sharing your work. There are many other outlets, including presentations at professional and scholarly conferences, oral presentations in other forums, continuing and in-service education, collaborative work with colleagues, and presentations on the World Wide Web. Sharing your work is not only useful to others but also helps you receive constructive criticism that will advance your own thinking and conceptual development.

Summary

Disseminating your research is a major and essential part of the research process. Sharing your work provides knowledge to others to inform practice, tests existing knowledge and theory, develops new knowledge and theory, and ultimately promotes the collective advancement of knowledge in health and human services.

References

1. Gitlin, L.N., Lyons, K.J. Successful grant writing: strategies for health and human service professionals, ed 2. New York: Springer, 2004.

2. Babbie, E. The basics of social research, ed 4. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, 2007.

3. Grinnell, R.M., Unrau, Y. Social work research and evaluation, ed 8. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

4. Ary, H., Jacobs, L.C., Razavieh, A. Introduction to research in education. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, 2002.

5. Consort Transparent Reporting of Trials (website), http://www.design.ncsu.edu/cud/. Accessed 4/2/2010.

6. Moher, D., Schulz, K.F., Altman, D.G. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-groups of randomized trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1911–1914.

7. Pink, S. Doing sensory ethnography. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2009.

8. Wolcott, H. Writing up qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2009.

9. Liebow, E. Tally's corner. Boston: Little, Brown, 1967.

10. Gubrium, J.F. Living and dying at Murray Manor. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1975.

11. Emerson, R.M., Fretz, R.I., Shaw, L.L. Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

12. Tashakkori, A., Teddue, C. Handbook of mixed methods in social sciences. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2002.

13. DePoy, E., Gilson, S.F. Evaluation practice. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008.

14. Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State, http://www.design.ncsu.edu/cud/. [Accessed 1997].

15. Vanderheiden, G. Fundamentals and priorities for design information and telecommunication technologies. In: Preiser W., Ostrow E., eds. Universal design handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:65.4.

16. Richardson, L. Writing strategies: reaching diverse audiences. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1990;34.

You read an article by an author, Dr. Smith, and in her review of the literature, she cited a number of other authors and their studies. You are interested in these other studies and include them in your study on the basis of your reading of Dr. Smith's article, and you cite them in your reference list. However, you have never obtained and read the original articles. In this case, you are actually using Dr. Smith's interpretations of these studies. Remember, Dr. Smith selected the most salient points from these studies that supported her particular approach. Therefore, her interpretation may be different from the intent of the original work. If you had read the articles yourself, you may have derived a different understanding. In writing a research report, only primary citations are acceptable.

You read an article by an author, Dr. Smith, and in her review of the literature, she cited a number of other authors and their studies. You are interested in these other studies and include them in your study on the basis of your reading of Dr. Smith's article, and you cite them in your reference list. However, you have never obtained and read the original articles. In this case, you are actually using Dr. Smith's interpretations of these studies. Remember, Dr. Smith selected the most salient points from these studies that supported her particular approach. Therefore, her interpretation may be different from the intent of the original work. If you had read the articles yourself, you may have derived a different understanding. In writing a research report, only primary citations are acceptable.