Developing a Knowledge Base Through Review of the Literature

Determine What Research Has Been Conducted on the Topic of Inquiry

Determine Level of Theory and Knowledge Development Relevant to Your Project

Determine Relevance of the Current Knowledge Base to Your Problem Area

With the explosion of information on the Internet, sources of information and knowledge beyond refereed articles and other scholarship appearing in print have been increasingly accepted as part of the “literature” review. In this chapter, we therefore use the term “literature” to refer to the broad spectrum of sources that are relevant to an investigation.

Most of us have had the experience of spending long hours at the library or on the Internet poring through literature and materials to discover what others have written about a topic of interest. Although you probably have participated in this type of activity for various classroom assignments, reviewing information for research is more systematic and serves more specific purposes.

One important purpose of reviewing the literature for research is to help sharpen the focus of your initial research interest and the specific strategy you plan to use to conduct a study. Discovering what others know and how they come to know it is an important function of the review when conducted at the initial stage of developing a research idea. The review, when conducted at this stage, involves a process by which the researcher critically assesses text and other relevant material that is directly and indirectly related to both the proposed topic and the potential strategies for conducting the research.

Another purpose of a literature review is to help determine how your research fits within an existing body of knowledge and what your research uniquely contributes to the scientific enterprise. Reviewing the literature for this purpose occurs as you are formulating your research ideas as well as when you are ready to write up your findings.

A literature review also serves as a source of data. For example, in certain forms of qualitative research, literature and other sources are brought in at different points of the research process to emphasize, elaborate, or reveal emergent themes. Likewise, a systematic literature review is used in quantitative, or experimental-type, methodologies to gather data, such as when the review forms the unit of analysis for a meta-analysis (see Chapter 9) or when ranking the level of evidence for a particular issue.

Thus, reviewing the literature is a significant thinking and action process in the world of research. However, it is often misunderstood and undervalued.

In this chapter, we begin our discussion with a presentation of the various reasons to conduct a literature review. We then detail the specific steps involved in conducting a literature review and share strategies that will help you accomplish this task. Because typically there is so much information directly related to any one topic, as well as literature from related bodies of research that also should be examined, the review process may initially seem overwhelming. However, some “tricks of the trade” can facilitate a systematic and comprehensive review process that is feasible, manageable, and even enjoyable.

Why review the literature?

There are four major reasons to review literature in research (Box 5-1). Let us examine each reason in depth.

Determine What Research Has Been Conducted on the Topic of Inquiry

Why should you conduct a study if it has already been done and done well or to your satisfaction? Here, the key words are “done well” and “to your satisfaction.” To determine whether the current literature is sufficient to help you solve a professional problem, you must critically evaluate how others have struggled with and resolved the same or a similar question. Most novice researchers think that they are not supposed to be critical of published literature. However, being critical is the very point of conducting the literature review. You are supposed to examine previous studies critically to determine whether these efforts were done well and whether they answer your question satisfactorily.

An initial review of the literature provides a sense of the previous work done in your area of interest. The review helps identify (1) the current trends and ways of thinking about your topic, (2) the contemporary debates in your field, (3) the gaps in the knowledge base, (4) the ways in which the current knowledge on your topic has been developed, and (5) the conceptual frameworks used to inform and examine your problem.

Sometimes an initial review of the literature will steer you in a research direction different from your original plan.

Determine Level of Theory and Knowledge Development Relevant to Your Project

As you review the literature, not only do you need to describe what exists, but more important, you need to analyze critically the knowledge level, knowledge generation, and study boundaries in each work (Box 5-2).

Level of Knowledge

When you read a study, first evaluate the level of knowledge that emerges from the study. As discussed in Chapter 7, studies produce varying levels of knowledge, from descriptive to theoretical. The level of theory development and knowledge in your topic area will strongly influence the type of research strategy you select. As you read related studies in the literature, consider the level of theoretical development. Is the body of knowledge descriptive, explanatory, or at the level of prediction? Typically in general inquiry, and necessarily in experimental-type inquiry, the development of knowledge proceeds incrementally such that the first wave of studies in a particular area will be descriptive and designed to describe the characteristics of the phenomenon. After the characteristics of a problem are described, researchers search for associations or relationships among factors that may help explain the phenomenon. On the basis of the findings from explanatory research, attempts may be made to study the phenomenon from a predictive perspective by either testing an intervention or developing causal models to explain the phenomenon further.

Identifying the level of knowledge in the area of interest helps you identify the next research steps.

How Knowledge Is Generated

After you have determined the level of knowledge of your particular area of interest, you need to evaluate how that knowledge has been generated. In other words, you need to review the literature carefully to identify the research strategy or design used in each study. Many people tend to read the introduction to a study, then jump to the discussion section or set of conclusions to see what it can tell them. However, it is important to read each aspect of a research report, especially the section on methodology. As you read about the design of a particular study, you must critically examine whether it is appropriate for the level of knowledge that the authors indicate exists in the literature and whether the conclusions of the study are consistent with the design strategy. This is an important critical analysis of the existing literature that you need to feel fully empowered to perform. You may be quite surprised to find that, unfortunately, the literature is full of research that demonstrates an inappropriate match among research question, strategy, and conclusions.

As you read a study, ask yourself the three interrelated questions in Box 5-3. The answers to these questions will help you understand and critically determine the appropriateness of the level of knowledge generated in your topic area. This understanding in turn will help to shape the direction of your research.

Boundaries of a Study

It is also important to determine the boundaries of the studies you are reviewing and their relevance to your study problem. By “boundaries” we mean the “who, what, when, and where” of a study.

If you do not find any literature in your topic area, you may choose to identify an analogous body of literature to provide direction in how to develop your strategy.

Determining the boundaries of the literature helps you to evaluate the level of knowledge that exists for the particular population and setting you are interested in studying. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has been vigilant about boundaries, recognizing that many studies are applied to populations that have not participated in the study. In efforts to redress this problem, NIH has instituted policies to include populations such as women, children, and minorities who have not been included in research.

Determine Relevance of the Current Knowledge Base to Your Problem Area

Once you have evaluated the level of knowledge advanced in the literature, you need to determine its relevance to your idea.

Let us assume you are considering conducting an experimental-type study. In your literature review, you must find research that points to a theoretical framework relevant to your topic and research that identifies specific variables and measures for inclusion in your study. Your literature review must also yield a body of sufficiently developed knowledge so that hypotheses can be derived for your study. In other words, in the experimental-type tradition, the literature provides the rationale and structure for everything that you investigate and for all action processes.

For each variable you choose to include in your study, even demographics, you must support or justify your inclusion of the variable on the basis of sound literature. Just think of all the extraneous information that could be introduced into a research study. For theoretical, ethical, and methodological soundness, experimental-type approaches require supportive literature for all variables.

If your literature review reveals a clear gap in existing knowledge or a poor fit between a phenomenon and current theory, you probably should consider a strategy in the naturalistic tradition.

With the addition of foundational work to literature and theory, researchers would have the rationale for selecting more diverse and complex design approaches to subsequent and related studies.

Provide a Rationale for Selection of the Research Strategy

After you have determined the content and structure of existing theory and knowledge related to your problem area, the next task is to determine a rationale for the selection of your research design. A literature review for a research grant proposal or a research report is written to support directly both your research and your choice of design. You must synthesize your critical review of existing studies in such a way that the reader sees your study as a logical extension of current knowledge in the literature. Look at Box 5-2 once again. The rationale for conducting an experimental-type design is well supported by the existence of case studies as well as the recommendations that are made by the investigators in their conclusions.

We now turn to the mechanics of how to conduct a literature search, then we offer guidelines for developing a written rationale.

How to conduct a literature search

Conducting a literature search and writing a literature review are exciting and creative processes. However, there may be so much literature and other resources in the area of interest that the review process can initially seem overwhelming. Six steps can guide you in the thinking and action processes of searching the literature, organizing the sources, and taking notes on the references that you plan to use in a written rationale (Box 5-4).

Step 1: Determine When to Conduct a Search

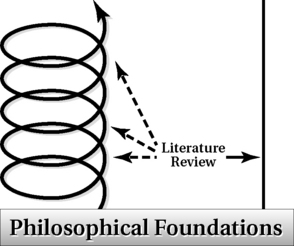

The first step in a literature review is the determination of when a review should be done. In studies in the experimental-type tradition, a literature review always precedes both the final formulation of a research question and the implementation of the study. In the experimental-type tradition, definitions of all variables studied and the level of theoretical complexity underpinning an inquiry must be presented for a study to be scientifically sound and rigorous. (We discuss “rigor” in greater detail in subsequent chapters.)

In the tradition of naturalistic inquiry, the literature may be reviewed at different points throughout the project. Although the literature is not critical for defining variables and instrumentation, it serves multiple purposes. For example, the literature may be used as an additional source of data and included as part of the information-gathering process that is subsequently analyzed and interpreted. Another purpose of the literature review in naturalistic inquiry is to inform the direction of data collection once the investigator is in the field. As discoveries occur in data collection, the investigator may turn to the literature for guidance about how to interpret emergent themes and identify other questions that should be asked in the field.

For example, consider the following scenario.

To the extreme are forms of naturalistic research in which no literature is reviewed before or during fieldwork. In a classic study of prison violence using an endogenous research design (discussed in more detail in Chapter 10), the researcher and the research team of prison inmates did not believe that a review was necessary or relevant to the purpose of their study.3

Usually, however, researchers working in the naturalistic-type tradition review the literature before conducting research to confirm the need for a naturalistic approach. For example, in the study by DePoy and Gilson discussed earlier, the literature provided the rationale for their approach.

Although an extensive review of the literature conducted before undertaking any further thinking or action processes refines the research approach and design, investigators are continually updating their literature review throughout their studies.

Step 2: Delimit What Is Searched

Once you have decided when to conduct a literature review, your next step involves setting parameters as to what is relevant to search; after all, it is not feasible or reasonable to review every topic that is “somewhat related” to your problem. Delimiting the search, or setting boundaries to the search, is an important but difficult step. The boundaries you set must ensure a review that is comprehensive but still practical and not overwhelming.

One useful strategy across all traditions is to base a search on the core concepts and constructs contained in the initial inquiry.

Similarly, these lexical concepts (concepts that are expressed as words) would help you begin a search using these variable names as keywords (words or phrases that are used in online searches to identify and categorize work that contains these specific concepts) to seek literature and determine how your topic has already been studied. As internet searches become the rule rather than the exception, the selection of key words is a critical skill to develop in order to hone and refine your search as well as for efficiency.

Step 3: Access Databases for Periodicals, Books, and Documents

Now that you have determined when the literature search will take place and have established some limits on what will be searched, you are ready to go to the computer at the library or in your home to search databases. Library searches have become technologically sophisticated and are a big advantage over previous searching mechanism such as card catalogues, which are now housed in antique stores. However, the most valuable resource for finding references in the library is still the reference librarian, who may be on site or online. Working with an experienced librarian is the best way to learn how to navigate physical and virtual libraries, find the best search words for your area of interest, and access the numerous databases that open the world of literature to you.

You have many choices about how to begin your search. You can access literature through an online database or through other indexes and abstracts. You can browse hard copies of journals, peruse museum exhibits and online sites relevant to your topic, lurk on listservs, or actively participate in dialogue to direct your search. In health and human service research, you will more likely want to search four categories of materials: books, online and paper journal articles, online resources such as collections of papers and scholarly blogs, and government documents. You may also find newspapers, news Web sites, and newsletters useful, especially those from professional associations. In addition, you can construct a literature search based on the references listed in the research studies and resources you obtain. However, do not depend exclusively on what other authors identify as important. References from other articles may not represent the broad range of studies you may need to review or the most current literature. A year or more may pass between submission of a manuscript and its publication; therefore, the citations that precede each article may be outdated for your needs.

Searching Periodicals and Journals

Most researchers begin their search by examining online and paper periodicals and journals. To begin your search, it is helpful and time-efficient to work with the online databases. Searching databases can be rewarding, but you must know how to use the system. You can search databases by examining subjects, authors, or titles of articles.

Let us first consider a search based on subject. Begin by identifying the major constructs and concepts of your initial inquiry (as discussed earlier). Then, translate these into keywords, which are used to identify works that contain the named concepts. In addition to the title, author, and abstract, most journals require authors to specify and list keywords that reflect the content of their study. Each database groups these studies according to these keywords.

For example, Box 5-5 presents part of a title page of a study on disability and domestic violence. Without these keywords, this study containing disability would not be likely to be identified in a search on domestic violence. This example illustrates how valuable keywords are in adding dimension to a study, ensuring that its future dissemination and use in research can be maximized.

You can obtain help from a reference librarian in formulating keywords, or the computer will help direct you to synonymous terms, if the words you initially select are not used as classifiers. Most online systems are “user-friendly” and interactive; that is, the computer provides step-by-step directions on what to do. If you search any of the keywords listed in Box 5-5, you will find significant studies in that topic area. Omit “disability” as a keyword, and see how your search changes.

Let us return to the example of the exercise study to show the importance of keywords. We will begin our search with the keywords “exercise” and “elder.” The combination of terms is critical in delimiting and focusing your search. For example, when we searched “Google Scholar,” an online database of journal and newspaper articles available to the public, we first entered the keyword “exercise.” The computer indicated 249,000 sources in the past 5 years relevant to the subject of exercise. A review of all these sources obviously would be too cumbersome. We then entered our second keyword, “elder,” at a prompt that requested further delimiting. The computer then searched for works containing both topics and indicated 20,600 articles.

This search raises another important issue. As database options expand, it is important to select options that are feasible. We conducted the same search on the Nursing and Allied Health Collection database that we accessed through the University of Maine. The keyword “exercise” yielded 2396 articles over the past 5 years. Adding the term “elder” decreased the number of articles to 56.

After your chosen database indicates how many citations are found, the next step is to display the sources. Often you have a choice of examining only the citation, the abstract, or the full text. If your online system is connected to a printer, you can select a print command and print your selections. You may also search the system by entering authors' names or words you believe may appear in the titles of sources. This entry expands your search to relevant articles that may not have included the combination of keywords initially used. The computer will search the references and compile a list of sources from which to choose.

In some cases, it is more efficient to ask the librarian to conduct a search for you. Large databases, such as the Educational Information Resources Information Center and Medline, although accessible without assistance, can be easily accessed in this manner. Librarians are also adept at selecting keywords that are productive and targeted to your topic.

You also may want to do a search in important indexes and abstracts, some of which are not available online, such as some library holdings of Dissertation Abstracts and government documents, to ensure that you have fully covered the literature relevant to your study. In health research, indexes and abstracts are numerous and are increasing as a result of the omnipotence of the Internet. We have listed just a few that we have found valuable in Box 5-6.

Among the many abstracting and indexing services, Ulrich's International Periodical Directory is especially useful because it lists all periodicals and databases in which these periodicals are indexed.

One major directory of abstracts that is not frequently used but is extremely helpful in locating sources is Dissertation Abstracts International. We mentioned this source because a literature review in a dissertation is usually exhaustive, and thus obtaining a dissertation in your topic area may provide a comprehensive literature review and bibliography that is immediately available to you.

Within the past several years, online book searching is extremely efficient, enjoyable, and rewarding. One site that is particularly noteworthy, albeit controversial, is Google Books, which provides snippets to full texts of books online. Catalogues listing the collections of libraries from universities across the globe can now be accessed online. We also find sites such as Amazon.com and book publishers extremely helpful in locating and accessing scholarship to support research.

Another strategy is to identify whether an article has been published that comprehensively reviews the literature in your area of interest. A literature review or a meta-analysis of studies on a particular area provides an excellent way to begin your literature search. Also, these reviews usually identify gaps in the literature and make recommendations as to next research steps.

Most beginning investigators are concerned with the number of sources to review. Although there is no magical number, most researchers search the literature for articles written within the previous 5 years. A search is extended beyond 5 years to evaluate the historical development of an issue or to review a breakthrough or classic article. The depth of a review depends on the purpose and scope of your study. Most investigators try to become familiar with the most important authors, studies, and papers in their topic area. You will have a sense that your review is comprehensive when you begin to see citations of authors you have already read, or if you are not finding material that leads to new learning. Also, do not hesitate to contact a researcher who has published in your topic area; ask about the researcher's recent work (which may not be published yet) and recommendations on specific current articles for you to review. You can also access the curriculum vitae of a researcher or, if the individual is noteworthy, an article on his or her work may be found on Wikipedia.

Step 4: Organize Information

With your list of sources identified by your searches, you are ready to retrieve and organize them. We usually begin by reading abstracts of journal articles or book contents to determine their value to the study. On the basis of the abstract or table of contents, we determine whether the scholarship fits one of four categories, as suggested by Findley.4 If a study is highly relevant, it goes into what Findley calls the “A” pile—those works that absolutely must be read. If the work appears somewhat relevant, it is placed in the “B” pile—those studies or sources that probably will be read, depending on the direction taken. If the source might be relevant, it goes into a “C” pile—those resources that may be read, depending on the direction taken. Finally, if a work is not relevant at all, it is put into an “X” pile—those that will not be read but will be kept, just in case.

Next, begin with the “A” pile, and classify the sources according to the major subjects or concepts. It is helpful to pick a reading order to outline a preliminary conceptual framework for your literature review.

Because it is not possible to remember all the important information presented in reading, note taking is critical. There are many schemes for note taking. Some find that taking notes on index cards is effective because they can be shuffled and reordered to fit into an outline. Others take notes on a database or word-processing system. In general, your notes should include a synopsis of the content, the conceptual framework for the work, the method, and a brief review of the findings. Whatever method you use, always be sure to cite the full reference. All researchers have had the miserable experience of losing the volume or page number of a critical source and then spending hours to find it later.

Although investigators organize and write notations in their own way, we offer two strategies—using a chart and using a concept/construct matrix—to help you organize your reading. These two organizational aids will also assist in the writing stage of your review.

Charting the Literature

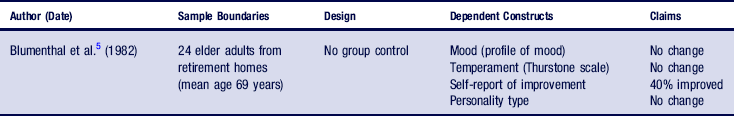

For a literature review chart, you select pertinent information from each work you review and record it using a chart format. To use a chart approach, you need to determine the categories of information you will extract from each resource to record or place on the chart. The categories you choose should reflect the nature of your research project and how you plan to develop a rationale for your study. For example, if you are planning an experimental exercise study for elder patients with diabetes, your review may need to highlight the limited number of adequately designed exercise studies with this particular population. Therefore, the categories of your chart might include the designs of previous studies and the health status of the samples. Table 5-1 shows an excerpt from such a chart. This chart would be used to structure a review of research on exercise intervention studies for healthy older adults and to evaluate research designs and specific outcomes of previous studies.

Charting research in this way allows you to reflect systematically on the literature as a whole and critically evaluate and identify research gaps.

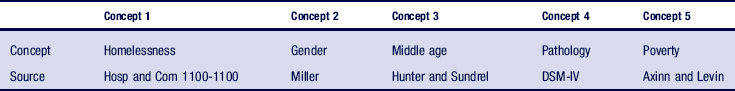

Concept/Construct Matrix

The concept/construct matrix organizes information that you have reviewed and evaluated by key concept/construct (the x axis) and source (the y axis). Table 5-2 shows an excerpt from a concept matrix.

TABLE 5-2

Excerpt from Butler's Concept/Construct Matrix

From Butler SS: Middle-aged, female and homeless: the stories of a forgotten group, New York, 1994, Garland.

As you begin to write the literature review, the concept/construct matrix facilitates quick identification of the scholarship that address the specific concepts/constructs you need to discuss. This approach also provides a mechanism to ensure that you review each core construct of your area of inquiry in the literature and systematically link to the others.

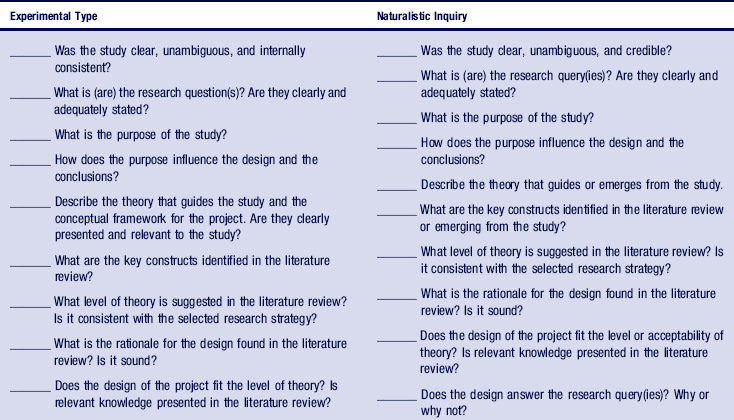

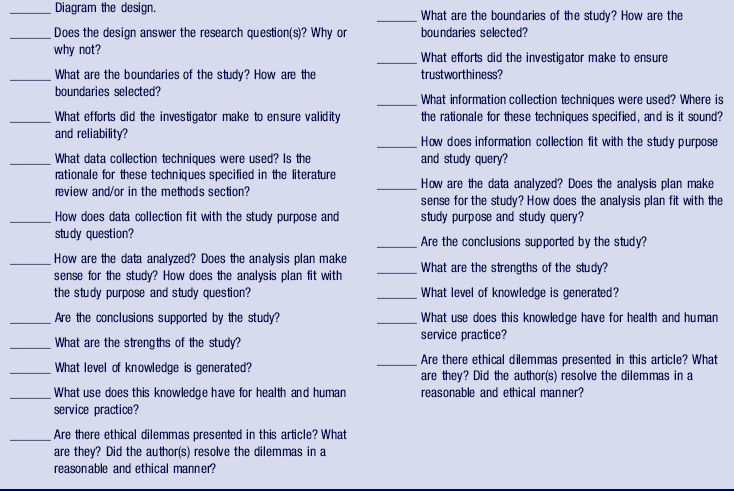

Step 5: Critically Evaluate the Literature

Several guiding questions can help you critically evaluate the literature you read. Use the questions in Table 5-3 to guide your reading of the research literature and the questions in Box 5-7 to assist your evaluation of nonresearch literature. Your responses to these evaluative questions will inform your research direction.

An evaluation of nonresearch sources involves examining the level of and support for the knowledge presented. Nonresearch sources include position papers, theoretical works, editorials, and debates. As mentioned earlier, another important resource is work that presents a critical review of research in a particular area. These published literature reviews provide syntheses of research as ways of summarizing the state of knowledge in particular fields and identifying new directions for research.

Step 6: Write the Literature Review

Now that you have searched, obtained, read, and organized your literature, it is time to write the actual review. You need to summarize your review for a proposal to seek approval from your institution's office for protection of human subjects, for a proposal to seek funding to support your research, or to justify the conduct of your study for a manuscript that describes the completed research project. A good literature review presents an overview of the relevant work on your topic and a critical evaluation of the works. There is no recipe for writing a narrative literature review. Most investigators, whether working in an experimental-type or naturalistic tradition, include in their narratives the categories of information shown in Box 5-8. One suggested outline for writing the narrative of a literature review is presented in Box 5-9.

Summary

The literature review is a critical evaluation of existing literature that is relevant to your study. Because it is a critical evaluation, reviewing the literature is a thinking process that involves piecing together and integrating diverse bodies of literature. The review provides an understanding of the level of theory and knowledge development that exists about your topic. This understanding is essential so that you can determine how your study fits into the construction of knowledge in the topic area.

The literature review is also an action process through which concepts are organized and sources are logically presented in a written review. The literature review chart and concept/construct matrix are two organizational tools that will help you conceptualize the literature and write an effective review. An effective written review convinces the reader that your study is necessary, and it represents the next step in knowledge building. Remember, the primary purposes of writing a literature review and including it in the written report of your research are to establish the conceptual foundation for your research, establish the specific content of your study, and, most important, provide a rationale for your research design.

Also, keep in mind that a systematic review of the literature can also function as a research methodology. Chapter 10 describes two methodologies that use published literature as the unit of analysis.6

References

1. Peters, J. The domestic violence myth acceptance scale: development and psychometric testing of a new instrument. Bangor: University of Maine, 2003. [Ph.D. Dissertation].

2. Sellers, S.L., Hunter, A.G. Private pains, public choices: Influence of problems in the family origin on career choices among a cohort of MSW students. Social Work Education. 2005;24:869–881.

3. Butler, S.S. Middle-aged, female and homeless: the stories of a forgotten group. New York: Garland, 1994.

4. Findley, T.M. The conceptual review of the literature or how to read more articles than you ever wanted to see in your entire LIFE. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;68:97–102.

5. Blumenthal, J.A., et al. Psychological and physiological effects of physical conditioning on the elderly. J Psychosom Res. 1982;26:505–510.

6. Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y. Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2005.

Now suppose you want to examine the extent to which mild aerobic exercise promotes cardiovascular fitness in the elder population. You find several studies that already document a positive outcome, but you question the methodologies used by these studies, including the type of exercise, the research design, and the criteria for inclusion of study participants. Also, you find that many authors suggest further inquiry is necessary to determine the particular exercises that promote cardiovascular fitness, as well as those that maintain joint mobility. Although this area is not what you had originally planned, the literature review refines your thinking and directs you to specific problem areas that need greater research attention than the one originally intended. You need to decide whether replication of the reported studies is important to verify study findings, whether replication with a different sample (e.g., racially and ethnically diverse elder persons not included in previous studies) would be important, and whether your focus should be modified according to the other recommendations specified in the literature (e.g., need to examine different forms of exercise for a wider range of health outcomes).

Now suppose you want to examine the extent to which mild aerobic exercise promotes cardiovascular fitness in the elder population. You find several studies that already document a positive outcome, but you question the methodologies used by these studies, including the type of exercise, the research design, and the criteria for inclusion of study participants. Also, you find that many authors suggest further inquiry is necessary to determine the particular exercises that promote cardiovascular fitness, as well as those that maintain joint mobility. Although this area is not what you had originally planned, the literature review refines your thinking and directs you to specific problem areas that need greater research attention than the one originally intended. You need to decide whether replication of the reported studies is important to verify study findings, whether replication with a different sample (e.g., racially and ethnically diverse elder persons not included in previous studies) would be important, and whether your focus should be modified according to the other recommendations specified in the literature (e.g., need to examine different forms of exercise for a wider range of health outcomes).