Anatomic and Biomechanical Principles Related to Splinting

1 Define the anatomical terminology used in splint prescriptions.

2 Relate anatomy of the upper extremity to splint design.

3 Identify arches of the hand.

4 Identify creases of the hand.

5 Articulate the importance of the hand’s arches and creases to splinting.

6 Recall actions and nerve innervations of upper extremity musculature.

7 Differentiate prehensile and grasp patterns of the hand.

8 Apply basic biomechanical principles to splint design.

9 Describe the correct width and length for a forearm splint.

10 Describe uses of padding in a splint.

11 Explain the reason splint edges should be rolled or flared.

12 Relate contour to splint fabrication.

13 Describe the change in skin and soft tissue mechanics with scar tissue, material application, edema, contractures, wounds, and infection.

Basic Anatomical Review for Splinting

Splinting requires sound knowledge of anatomic terminology and structures, biomechanics, and the way in which pathologic conditions impair function. Knowledge of anatomic structures is necessary in the choice and fabrication of a splint. This knowledge also influences the therapeutic regimen and home program. The following is a brief overview of anatomic terminology, proximal-to-distal structures, and landmarks of the upper extremity pertinent to the splinting process. It is neither comprehensive nor all-inclusive. For more depth and breadth in anatomic review, access an anatomy text, anatomic atlas, or compact disk [Colditz and McGrouther 1998] showing anatomic structures.

Terminology

Knowing anatomic location terms is extremely important when a therapist receives a splint prescription or is reading professional literature. In rehabilitation settings, the word arm usually refers to the area from the shoulder to the elbow (humerus). The term antecubital fossa refers to the depression at the bend of the elbow. Forearm is used to describe the area from the elbow to the wrist, which includes the radius and ulna. Carpal or carpus refers to the wrist or the carpal bones. Different terminology can be used to refer to the thumb and fingers. Narrative names include thumb, index, middle or long, ring, and little fingers. A numbering system is used to refer to the digits (Figure 4-1). The thumb is digit 1, the index finger is digit II, the middle (or long) finger is digit III, the ring finger is digit IV, and the little finger is digit V.

The terms palmar and volar are used interchangeably and refer to the front or anterior aspect of the hand and forearm in relationship to the anatomic position. The term dorsal refers to the back or posterior aspect of the hand and forearm in relationship to the anatomic position. Radial indicates the thumb side, and ulnar refers to the side of the fifth digit (little finger). Therefore, if a therapist receives an order for a dorsal wrist splint the physician has ordered a splint that is to be applied on the back of the hand and wrist. Another example of location terminology in a splint prescription is a radial gutter thumb spica splint. The therapist applies this type of splint to the thumb side of the hand and forearm.

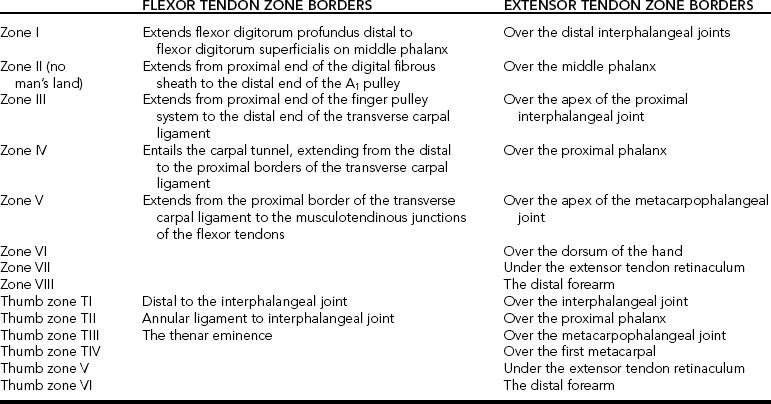

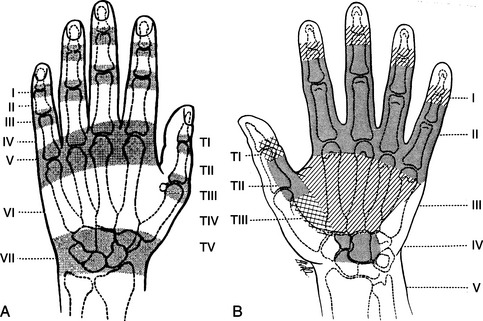

Literature addressing hand injuries and rehabilitation protocols often refers to zones of the hand.Figure 4-2 diagrams the zones of the hand [Kleinert et al. 1981].Table 4-1 presents the zones’ borders. Therapists should be familiar with these zones for understanding literature, conversing with other health providers, and documenting pertinent information.

Shoulder Joint

The shoulder complex comprises seven joints, including the glenohumeral, suprahumeral, acromioclavicular, scapulocostal, sternoclavicular, costosternal, and costovertebral joints [Cailliet 1981]. The suprahumeral and scapulocostal joints are pseudojoints, but they contribute to the shoulder’s function. Mobility of the shoulder is a compilation of all seven joints. Because the shoulder is extremely mobile, stability is sacrificed. This is evident when one considers that the head of the humerus articulates with approximately a third of the glenoid fossa. The shoulder complex allows motion in three planes, including flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and internal and external rotation.

The scapula is intimately involved with movement at the shoulder. Scapulohumeral rhythm is a term used to describe the coordinated series of synchronous motions, such as shoulder abduction and elevation.

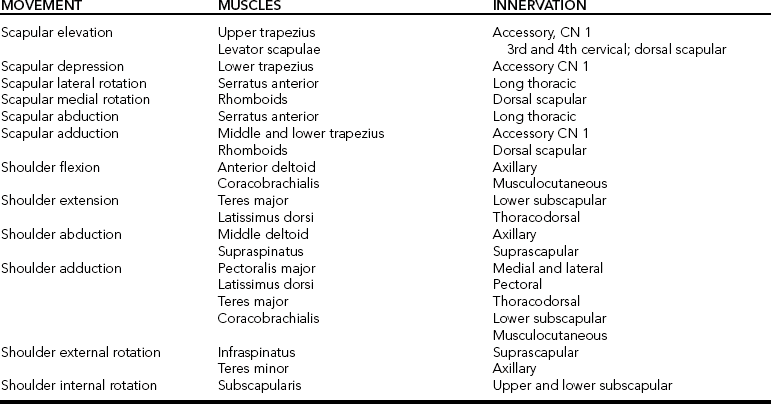

A complex of ligaments and tendons provides stability to the shoulder. Shoulder ligaments are named according to the bones they connect. The ligaments of the shoulder complex include the coracohumeral ligament and the superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments [Kapandji 1970]. The rotator cuff muscles contribute to the dynamic stability of the shoulder by compressing the humeral head into the glenoid fossa [Wu 1996]. The rotator cuff muscles include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.Table 4-2 lists the muscles involved with scapular and shoulder movements.

Elbow Joint

The elbow joint complex consists of the humeroradial, humeroulnar, and proximal radioulnar joints. The humeroradial joint is an articulation between the humerus and the radius. The humeroradial joint has two degrees of freedom that allow for elbow flexion and extension and forearm supination and pronation. The humerus articulates with the ulna at the humeroulnar joint. Flexion and extension movements take place at the humeroulnar joint. Elbow flexion and extension are limited by the articular surfaces of the trochlea of the ulna and the capitulum of the humerus.

The medial and lateral collateral ligaments strengthen the elbow capsule. The radial collateral, lateral ulnar, accessory lateral collateral, and annular ligaments constitute the ligamentous structure of the elbow.

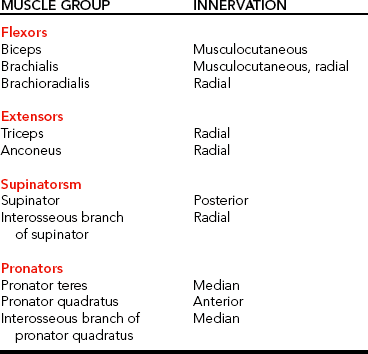

Muscles acting on the elbow can be categorized as functional groups: flexors, extensors, flexor-pronators, and extensor-supinators.Table 4-3 lists the muscles in these groups and their innervation.

Wrist Joint

The wrist joint is frequently incorporated into a splint’s design. A therapist must be knowledgeable of the wrist joint structure to appropriately choose and fabricate a splint that meets therapeutic objectives. The osseous structure of the wrist and hand consists of the ulna, radius, and eight carpal bones. Several joints are associated with the wrist complex, including the radiocarpal, midcarpal, and distal radioulnar joints.

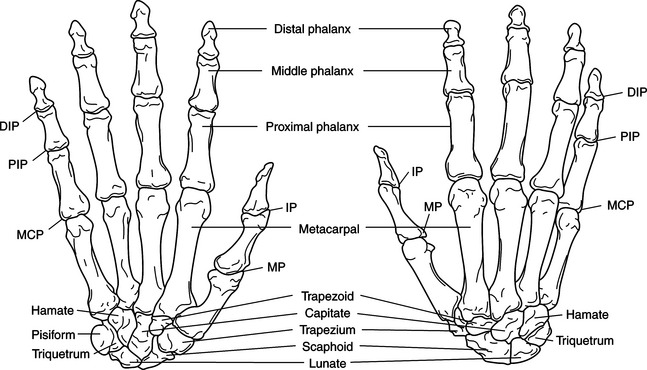

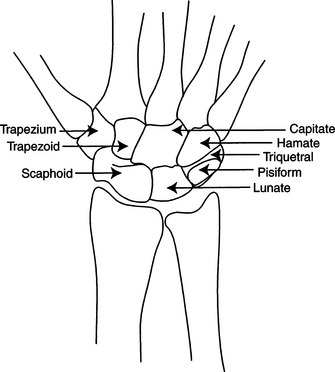

The carpal bones are arranged in two rows (Figure 4-3). The proximal row of carpal bones includes the scaphoid (navicular), lunate, and triquetrum. The pisiform bone is considered a sesamoid bone [Wu 1996]. The distal row of carpal bones comprises the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate. The distal row of carpal bones articulates with the metacarpals.

Figure 4-3 Carpal bones. Proximal row: scaphoid, lunate, pisiform, and triquetrum. Distal row: trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate. [From Pedretti LW (ed.), (1996). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 320.]

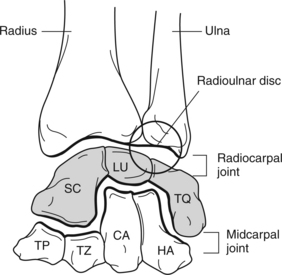

The radius articulates with the lunate and scaphoid in the proximal row of carpal bones. This articulation is the radiocarpal joint, which is mobile. The radiocarpal joint (Figure 4-4) is formed by the articulation of the distal head of the radius and the scaphoid and lunate bones. The ulnar styloid is attached to the triquetrum by a complex of ligaments and fibrocartilage. The ligaments bridge the ulna and radius and separate the distal radioulnar joint and the ulna from the radiocarpal joint. Motions of the radiocarpal joint include flexion, extension, and radial and ulnar deviation. The majority of wrist extension occurs at the midcarpal joint, with less movement occurring at the radiocarpal joint [Kapandji 1970].

Figure 4-4 Radiocarpal and midcarpal joints. [From Norkin C, Levangie P (1983). Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, p. 217.]

F. A. Davis.The midcarpal joint (Figure 4-4) is the articulation between the distal and proximal carpal rows. The joint exists, although there are no interosseous ligaments between the proximal and distal rows of carpals [Buck 1995]. The joint capsules remain separate. However, the radiocarpal joint capsule attaches to the edge of the articular disk, which is distal to the ulna [Pratt 1991]. The wrist motions of flexion, extension, and radial and ulnar deviation also take place at this joint. The majority of wrist flexion occurs at the radiocarpal joint. The midcarpal joint contributes less movement for wrist flexion [Kapandji 1970].

The distal radioulnar joint is an articulation between the head of the ulna and the distal radius. Forearm supination and pronation occur at the distal radioulnar joint.

Wrist stability is provided by the close-packed positions of the carpal bones and the interosseous ligaments [Wu 1996]. The intrinsic intercarpal ligaments connect carpal bone to carpal bone. The extrinsic ligaments of the carpal bones connect with the radius, ulna, and metacarpals. The ligaments on the volar aspect of the wrist are thick and strong, providing stability. The dorsal ligaments are thin and less developed [Wu 1996]. In addition, the intercarpal ligaments of the distal row form a stable fixed transverse arch [Chase 1990]. Ligaments of the wrist cover the volar, dorsal, radial, and ulnar areas. The ligaments in the wrist serve to stabilize joints, guide motion, limit motion, and transmit forces to the hand and forearm. These ligaments also assist in prevention of dislocations. The wrist contributes to the hand’s mobility and stability. Having two degrees of freedom (movements occur in two planes), the wrist is capable of flexing, extending, and deviating radially and ulnarly.

Finger and Thumb Joints

Cutaneous and Connective Coverings of the Hand

The skin is the protective covering of the body. There are unique characteristics of volar and dorsal skin, which are functionally relevant. The skin on the palmar surface of the hand is thick, immobile, and hairless. It contains sensory receptors and sweat glands. The palmar skin attaches to the underlying palmar aponeurosis, which facilitates grasp [Bowers and Tribuzi 1992]. Palmar skin is different from the skin on the dorsal surface of the hand. The dorsal skin is thin, supple, and quite mobile. Thus, it is often the site for edema accumulation. The skin on the dorsum of the hand accommodates to the extremes of the fingers’ flexion and extension movements. The hair follicles on the dorsum of the hand assist in protecting as well as activating touch receptors when the hair is moved slightly [Bowers and Tribuzi 1992].

Palmar Fascia

The superficial layer of palmar fascia in the hand is thin. Its composition is highly fibrous and is tightly bound to the deep fascia. The deep fascia thickens at the wrist and forms the palmar carpal ligament and the flexor retinaculum. The fascia thins over the thenar and hypothenar eminences but thickens over the midpalmar area and on the volar surfaces of the fingers. The fascia forms the palmar aponeurosis and the fibrous digital sheaths [Buck 1995].

The superficial palmar aponeurosis consists of longitudinal fibers that are continuous with the flexor retinaculum and palmaris longus tendon. The flexor tendons course under the flexor retinaculum. With absence of the flexor retinaculum, as in carpal tunnel release, bowstringing (Figure 4-5) of the tendons may occur at the wrist level. The distal borders of the superficial palmar aponeurosis fuse with the fibrous digital sheaths. The deep layer of the aponeurosis consists of transverse fibers, which are continuous with the thenar and hypothenar fascias. Distally, the deep layer forms the superficial transverse metacarpal ligament [Buck 1995]. The extensor retinaculum is a fibrous band that bridges over the extensor tendons. The deep and superficial layers of the aponeurosis form this retinaculum.

Figure 4-5 Bowstringing of the flexor tendons. [From Stewart-Pettengill KM, van Strien G (2002). Postoperative management of flexor tendon injuries. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Skirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 434.]

Functionally, the fascial structure of the hand protects, cushions, restrains, conforms, and maintains the hand’s arches [Bowers and Tribuzi 1992]. Therapists may splint persons with Dupuytren’s disease, in which the palmar fascia thickens and shortens.

Joint Structure

Splints often immobilize or mobilize joints of the fingers and thumb. Therefore, a therapist must have knowledge of these joints. The hand skeleton comprises five polyarticulated rays (Figure 4-6). The radial ray or first ray (thumb) is the shortest and includes three bones: a metacarpal and two phalanges. Joints of the thumb include the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint, the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint, and the interphalangeal (IP) joint (Figure 4-6). Functionally, the thumb is the most mobile of the digits. The thumb significantly enhances functional ability by its ability to oppose the pads of the fingers, which is needed for prehension and grasp. The thumb has three degrees of freedom, allowing for flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and opposition. The second through fifth rays comprise four bones: a metacarpal and three phalanges. Joints of the fingers include the MCP joint, proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, and the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. The digits are unequal in length. However, their respective lengths contribute to the hand’s functional capabilities.

The thumb’s metacarpotrapezial or CMC joint is saddle shaped and has two degrees of freedom, allowing for flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction movements. The CMC joints of the fingers have one degree of freedom to allow for small amounts of flexion and extension.

The fingers’ and thumb’s MCP joints have two degrees of freedom: flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. The convex metacarpal heads articulate with shallow concave bases of the proximal phalanges. Fibrocartilaginous volar plates extend the articular surfaces on the base of the phalanges. As the finger’s MCP joint is flexed, the volar plate slides proximally under the metacarpal. This mechanism allows for significant range of motion. The volar plate movement is controlled by accessory collateral ligaments and the metacarpal pulley for the long flexor tendons to blend with these structures.

During extension, the MCP joint is able to move medially and laterally. During MCP extension, collateral ligaments are slack. When digits II through V are extended at the MCP joints, finger abduction movement is free. Conversely, when the MCP joints of digits II through V are flexed abduction is extremely limited. The medial and lateral collateral ligaments of the metacarpal heads become taut and limit the distance by which the heads can be separated for abduction to occur. Mechanically, this provides stability during grasp.

Digits II through V have two interphalangeal joints: a PIP joint and a DIP joint. The thumb has only one IP joint. The IP joints have one degree of freedom, contributing to flexion and extension motions. IP joints have a volar plate mechanism similar to the MCP joints, with the addition of check reign ligaments. The check reign ligaments limit hyperextension.

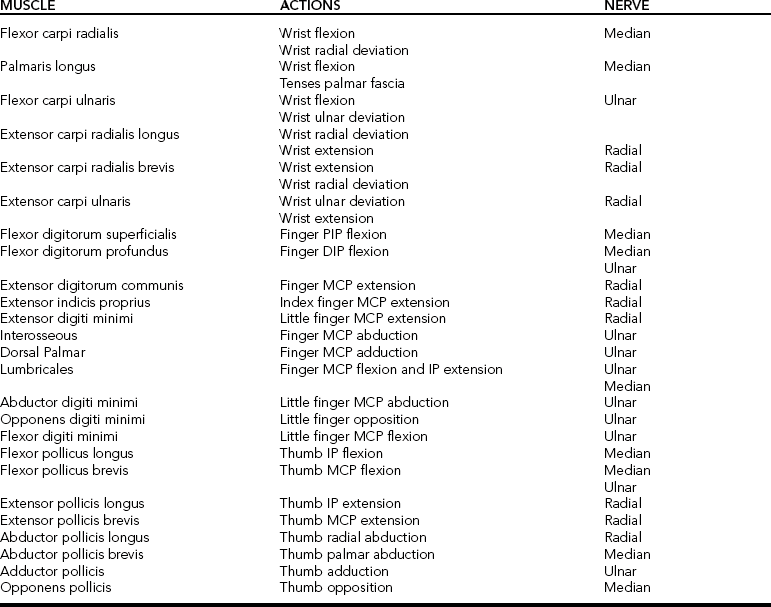

Table 4-4 provides a review of muscle actions and nerve supply of the wrist and hand [Clarkson and Gilewich 1989]. Muscles originating in the forearm are referred to as extrinsic muscles. Intrinsic muscles originate within the hand. Each group contributes to upper extremity function.

Extrinsic Muscles of the Hand

Extrinsic muscles acting on the wrist and hand can be further categorized as extensor and flexor groups. Extrinsic muscles of the wrist and hand are listed inBox 4-1. Extrinsic flexor muscles are most prominent on the medial side of the upper forearm. The function of extrinsic flexor muscles includes flexion of joints between the muscles’ respective origin and insertion. Extrinsic muscles of the hand and forearm accomplish flexion and extension of the wrist and the phalanges (fingers). For example, the flexor digitorum superficialis flexes the PIP joints of digits II through V, whereas the flexor digitorum profundus primarily flexes the DIP joints of digits II through V.

Because these tendons pass on the palmar side of the MCP joints, they tend to produce flexion of these joints. During grasp, flexion of the MCPs is necessary to obtain the proper shape of the hand. However, flexion of the wrist is undesirable because it decreases the grip force. The synergic contraction of the wrist extensors during finger flexion prevents wrist flexion during grasp.

The force of the extensor contraction is proportionate to the strength of the grip. The stronger the grip the stronger the contraction of the wrist extensors [Smith et al. 1996]. Digit extension and flexion are a combined effort from extrinsic and intrinsic muscles.

At the level of the wrist, the extensor tendons organize into six compartments [Fess et al. 2005]. The first compartment consists of tendons from the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB). When the radial side of the wrist is palpated, it is possible to feel the taut tendons of the APL and EPB.

The second compartment contains tendons of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and brevis (ECRB). A therapist can palpate the tendons on the dorsoradial aspect of the wrist by applying resistance to an extended wrist.

The third compartment houses the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL). This tendon passes around Lister’s tubercle of the radius and inserts on the dorsal base of the distal phalanx of the thumb.

The fourth compartment includes the four communis extensor (EDC) tendons and the extensor indicis proprius (EIP) tendon, which are the MCP joint extensors of the fingers.

The fifth compartment includes the extensor digiti minimi (EDM), which extends the little finger’s MCP joint. The EDM acts alone to extend the little finger.

The sixth compartment consists of the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU), which inserts at the dorsal base of the fifth metacarpal. A taut tendon can be palpated over the ulnar side of the wrist just distal to the ulnar head.

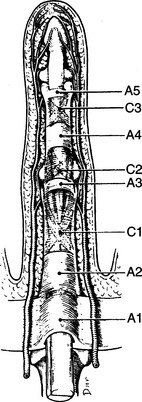

Unlike the other fingers, the index and little fingers have dual extensor systems comprising the EIP and the EDM in conjunction with the extensor digitorum communis. The EIP and EDM tendons lie on the ulnar side of the extensor digitorum communis tendons. Each finger has a flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon. Five annular (or A) pulleys and four cruciate (or C) pulleys prevent the flexor tendons from bowstringing (Figure 4-7).

Figure 4-7 Annular (A) and cruciate (C) pulley system of the hand. The digital flexor sheath is formed by five annular (A) pulleys and three cruciate (C) bands. The second and fourth annular pulleys are the most important for function. [From Tubiana R, Thomine JM, Mackin E (1996). Examination of the Hand and Wrist. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 81.]

In relationship to splinting, when pathology affects extrinsic musculature the splint design often incorporates the wrist and hand. This wrist-hand splint design is necessary because the extrinsic muscles cross the wrist and hand joints.

Intrinsic Muscles of the Hand and Wrist

The intrinsic muscles of the thumb and fingers are listed inBox 4-2. The intrinsic muscles are the muscles of the thenar and hypothenar eminences, the lumbricals, and the interossei. Intrinsic muscles can be grouped according to those of the thenar eminence, the hypothenar eminence, and the central muscles between the thenar and hypothenar eminences. The function of these intrinsic hand muscles produces flexion of the proximal phalanx and extension of the middle and distal phalanges, which contribute to the precise finger movements required for coordination.

The thenar eminence comprises the opponens pollicis, flexor pollicis brevis, adductor pollicis, and abductor pollicis brevis. The thenar eminence contributes to thumb opposition, which functionally allows for grasp and prehensile patterns. The thumb seldom acts alone except when pressing objects and playing instruments [Smith et al. 1996]. However, without a thumb the hand is virtually nonfunctional.

The hypothenar eminence includes the abductor digiti minimi, the flexor digiti minimi, the palmaris brevis, and the opponens digiti minimi. Similar to the thenar muscles, the hypothenar muscles also assist in rotating the fifth digit during grasp [Aulicino 1995].

The muscles of the central compartment include lumbricals and palmar and dorsal interossei. The interossei muscles are complex, with variations in their origins and insertions [Aulicino 1995]. There are four dorsal interossei and three palmar interossei muscles. The four lumbricals are weaker than the interossei. The lumbricals originate on the radial aspect of the flexor digitorum profundus tendons and insert on the extensor expansion of the finger. They are the only muscles in the human body with a moving origin and insertion. The primary function of the lumbricals is to flex the MCP joints [Wu 1996].

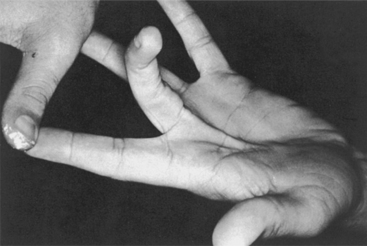

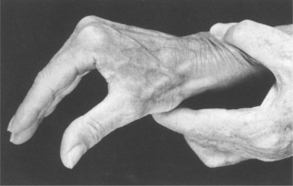

Normally, the interossei extend the PIP and DIP joints when the MCP joint is in extension. The dorsal interossei produce finger abduction, and the palmar interossei produce finger adduction. Functionally, the first dorsal interossei is a strong abductor of the index finger, which assists in properly positioning the hand for pinching. Research shows the interossei are active during grasp and power grip in addition to pinch [Long et al. 1970]. With function of the interossei and lumbricals, a person is able to place the hand in an intrinsic plus position. An intrinsic plus position is established when the MCP joints are flexed and the PIP joints are fully extended (Figure 4-8). Some injuries may result in an intrinsic minus hand (Figure 4-9) caused by paralysis or contractures. With an intrinsic minus hand, the person loses the cupping shape of the hand [Aulicino 1995]. In addition, the intrinsic musculature may waste or atrophy. In relationship to splinting, if intrinsic muscles are solely affected the splint design will often involve only immobilizing or mobilizing the finger joints as opposed to incorporating the wrist. To facilitate function and prevent deformity, joint positioning in splints frequently warrants an intrinsic plus posture rather than an intrinsic minus position.

Figure 4-8 Intrinsic plus position of the hand. MCP flexion with PIP extension. [From Tubiana R, Thomine JM, Mackin E (1996). Examination of the Peripheral Nerve Function in the Upper Extremity. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 308.]

Figure 4-9 (A) Intrinsic minus position of the hand. (B) Notice loss of normal arches of the hand and wasting of all intrinsic musculature resulting from a long-standing low median and ulnar nerve palsy. [From Aulicino PL (2002). Clinical examination of the hand. In EJ Mackin, AD Callahan, TM Skirven, LH Schneider, AL Osterman (eds.), Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 130.]

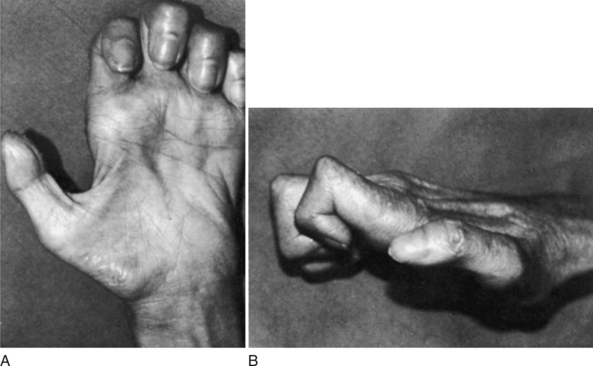

Arches of the Hand

To have a strong functional grasp, the hand uses the following three arches: (1) the longitudinal arch, (2) the distal transverse arch, and (3) the proximal transverse arch (Figure 4-10). Because of their functional significance, these arches require care during the splinting process for their preservation. The therapist should never splint a hand in a flat position because doing so compromises function and creates deformity. Especially in cases of muscle atrophy (as with a tendon or nerve injury), the splint should maintain integrity and mobility of the arches.

Figure 4-10 Arches of the hand: longitudinal arch (1), distal transverse arch (2), and proximal transverse arch (3).

The proximal transverse arch is fixed and consists of the distal row of carpal bones. It is a rigid arch acting as a stable pivot point for the wrist and long-finger flexor muscles [Chase 1990]. The transverse carpal ligament and the bones of the proximal transverse arch form the carpal tunnel. The finger flexor tendons pass beneath the transverse carpal ligament. The transverse carpal ligament provides mechanical advantage to the finger flexor tendons by serving as a pulley [Andrews and Bouvette 1996].

The distal transverse arch, which deepens with flexion of the fingers, is mobile and passes through the metacarpal heads [Malick 1972]. A splint must allow for the functional movement of the distal arch to maintain or increase normal hand function [Chase 1990].

The longitudinal arch allows the DIP, PIP, and MCP joints to flex [Fess et al. 2005]. This arch follows the longitudinal axes of each finger. Because of the mobility of their base, the first, fourth, and fifth metacarpals move in relationship to the shape and size of an object placed in the palm. Grasp is the result of holding an object against the rigid portion of the hand provided by the second and third digits. The flattening and cupping motions of the palm allow the hand to pick up and handle objects of various sizes.

Anatomic Landmarks of the Hand

The creases of the hand are critical landmarks for splint pattern making and molding. Therefore, knowledge of the creases and their functional implications is important. Three flexion creases are located on the palmar surface of digits II through V, and additional creases are located on the palmar surface of the hand and wrist (Figure 4-11).

Figure 4-11 Creases of the hand: distal digital (DIP) crease (1), middle digital (PIP) crease (2), proximal digital (MCP) crease (3), distal palmar crease (4), proximal palmar crease (5), thenar crease (6), distal wrist crease (7), and proximal wrist crease (8).

The three primary palmar creases are the distal, proximal, and thenar creases. As shown inFigure 4-11, the distal palmar crease extends transversely from the fifth MCP joint to a point midway between the third and second MCP joints [Cailliet 1994]. This crease is the landmark for the distal edge of the palmar portion of a splint intended to immobilize the wrist while allowing motion of the MCPs. By positioning the splint proximal to this crease, the therapist makes full MCP joint flexion possible. Below the distal palmar crease is the proximal palmar crease, which is used as a guide during splint fabrication. A splint must be proximal to the proximal palmar crease at the index finger or the MCP joint will not be free to move into flexion.

The thenar crease begins at the proximal palmar crease and curves around the base of the thenar eminence (seeFigure 4-11) [Cailliet 1994]. To allow thumb motion, this crease should define the limit of the splint’s edge. If the splint extends beyond the thenar crease toward the thumb, thumb opposition and palmar abduction of the CMC joint are inhibited.

The two palmar (or volar) wrist creases are the distal and proximal wrist creases. The distal wrist crease extends from the pisiform bone to the tubercle of the trapezium (seeFigure 4-11) and forms a line that separates the proximal and distal rows of the carpal bones. The proximal wrist crease corresponds to the radiocarpal joint and delineates the proximal border of the carpal bones, which articulates with the distal radius [Cailliet 1994]. The distal and proximal wrist creases assist in locating the axis of the wrist motion [Clarkson and Gilewich 1989].

The three digital palmar flexion creases are on the palmar aspect of digits II through V (seeFigure 4-11). The distal digital crease (or DIP crease) marks the DIP joint axis, and the middle digital crease (or PIP crease) marks the PIP joint axis. The proximal digital crease (or MCP crease) is distal to the MCP joint axis at the base of the proximal phalanx. The creation of the proximal and distal palmar creases results from the thick palmar skin folding due to the force allowing full MCP flexion [Malick 1972]. The flexion axis of the IP joint of the thumb corresponds to the IP crease of the thumb. Similarly, the MCP crease describes the axis of thumb MCP joint flexion.

The creases are close to but not always directly over bony joints [Chase 1990]. When splinting to immobilize a particular joint, the therapist must be sure to include the corresponding joint flexion crease within the splint so as to provide adequate support for immobilization. Conversely, when attempting to mobilize a specific joint the therapist must not incorporate the corresponding flexion crease in the splint to allow for full range of motion [Fess et al. 2005]. When one is working with persons who have moderate to severe edema, the creases may dissipate. Creases may also dissipate with disuse associated with paralysis or disuse resulting from pain, stiffness, or psychological problems.

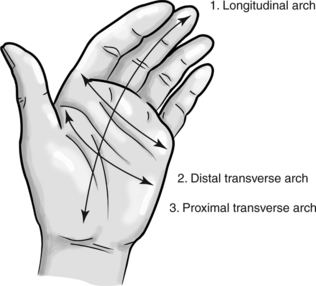

Grasp and Prehensile Patterns

The normal hand can perform many prehensile patterns in which the thumb is a crucial factor. Therapists must be knowledgeable about prehensile and grasp patterns, especially when splinting to assist the performance of these patterns.

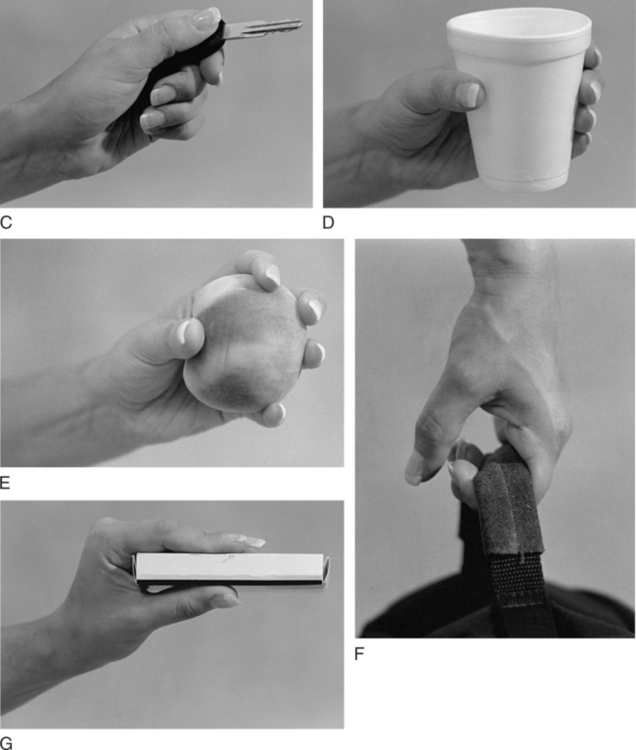

Even though hand movements are extremely complex, they can be categorized into several basic prehensile and grasp patterns, including fingertip prehension, palmar prehension, lateral prehension, cylindrical grasp, spherical grasp, hook grasp [Smith et al. 1996], and intrinsic plus grasp [Belkin and English 1996].Figure 4-12 depicts these types of prehensile and grip patterns. Therapists should keep in mind that finer prehensile movements require less strength than grasp movements. Pedretti [1990, p. 405] remarked, “The grasp and prehension patterns that may be provided by hand splinting are determined by the muscles that are functioning, potential and present deformities, and how the hand is to be used.”

Figure 4-12 Prehensile and grip patterns of the hand. (A) Fingertip prehension, (B) palmar prehension, (C) lateral prehension, (D) cylindrical grasp, (E) spherical grasp, (F) hook grasp, and (G) intrinsic plus grasp.

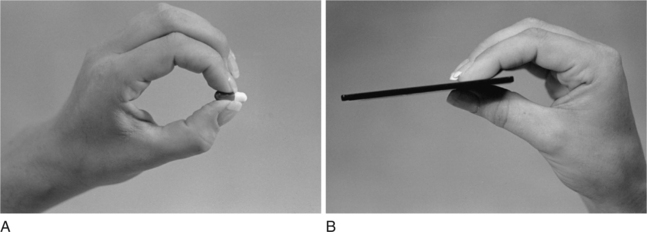

Fingertip prehension is the contact of the pad of the index or middle finger with the pad of the thumb [Smith et al. 1996]. This movement, which clients use to pick up small objects such as beads and pins, is the weakest of the pinch patterns and requires fine motor coordination. A splint to facilitate the fingertip prehension for a person with arthritis may include a static splint to block (stabilize) the thumb IP joint in slight flexion (Figure 4-13) [Belkin and English 1996].

Figure 4-13 Static splint to block the thumb IP joint in slight flexion to facilitate tip pinch. [From Pedretti LW (ed.), (1996). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 327.]

Palmar prehension, also known as the tripod or three jaw chuck pinch [Clarkson and Gilewich 1989, Belkin and English 1996], is the contact of the thumb pad with the pads of the middle and index fingers. People use palmar prehension for holding pencils and picking up small spherical objects. Splints to facilitate palmar prehension include thumb spica splints that position the thumb in palmar abduction, which may be hand or forearm based (Figure 4-14).

Figure 4-14 Thumb spica splint to facilitate palmar prehension by positioning the thumb in opposition to the index and long fingers. [From Pedretti LW (ed.), (1996). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 327.]

Lateral prehension, the strongest of the pinch patterns, is the contact between the thumb pad and the lateral aspect of the index finger [Smith et al. 1996]. Clients typically use this pattern for holding keys. Splints that position the hand for lateral prehension include thumb spica splints that place the thumb in slight radial abduction (Figure 4-15).

Figure 4-15 Thumb spica splint to facilitate lateral prehension by positioning the thumb in lateral opposition to the index finger. [From Pedretti LW (ed.), (1996). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 327.]

Cylindrical grasp is used for holding cylindrical-shaped objects such as soda cans, pan handles, and cylindrical tools [Smith et al. 1996]. The object rests against the palm of the hand, and the adducted fingers flex around the object to maintain a grasp. Splinting to encourage such motions as thumb opposition or finger and thumb joint flexion may contribute to a person’s ability to regain cylindrical grasp (Figure 4-16).

Figure 4-16 This dorsal wrist splint stabilizes the wrist to increase grip force and minimizes coverage of the palm. [From Pedretti LW (ed.), (1996). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 328.]

The spherical grasp is used to hold round objects such as tennis balls and baseballs [Smith et al. 1996]. The object rests against the palm of the hand, and the abducted five digits flex around the object. Splinting to enhance spherical grasp may include splints addressing such motions as finger and thumb abduction (Figure 4-17).

Figure 4-17 This dorsal wrist splint stabilizes the wrist and allows MCP mobility required for a spherical grasp. [From Pedretti LW (ed.), (1996). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 328.]

The hook grasp, which is accomplished with the fingers only, involves the carrying of such items as briefcases and suitcases by the handles [Smith et al. 1996]. The PIPs and DIPs flex around the object, and the thumb often remains passive in this type of grasp. With ulnar and median nerve damage, this position may be avoided rather than encouraged. However, for PIP and DIP joints lacking flexion a therapist may fabricate dynamic flexion splints to gain range of motion in these joints.

The intrinsic plus grip is characterized by MCP flexion and PIP and DIP extension. The thumb is positioned in palmar abduction for opposition with the third and fourth fingers [Belkin and English 1996]. This grasp is helpful in holding flat objects such as books, trays, or sandwiches. The intrinsic plus grip is not present with ulnar and median nerve injuries. A therapist may facilitate the grasp by using a figure-of-eight splint, shown inFigure 4-18.

Biomechanical Principles of Splinting

Splinting involves application of external forces on the hand, and thus understanding basic biomechanical principles is important for the therapist when constructing and fitting a splint. Correct biomechanics of a splint design results in an optimal fit and reduces risks of skin irritation and pressure areas, which ultimately may lead to client comfort, compliance, and function. In addition, knowledgeable manipulation of biomechanics increases splint efficiency and improves splint durability while decreasing cost and frustration [Fess 1995].

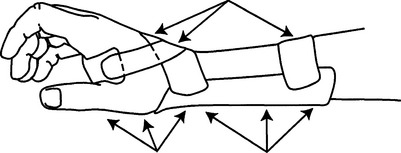

Three-point Pressure

Most splints use a three-point pressure system to affect a joint motion. A three-point pressure system consists of three individual linear forces in which the middle force is directed in an opposite direction from the other two forces, as depicted inFigure 4-19. Three-point pressure systems in splints are used for different purposes [Fess 1995, Andrews and Bouvette 1996]. For example, a splint affecting extension or flexion of a joint exerts forces in one plane or unidirectionally, as shown inFigure 4-20. Three-point systems can be applied to multiple directions. In other words, a splint may immobilize one joint while mobilizing an adjacent joint. An example of a multidirectional three-point pressure system is a circumferential wrist splint, shown inFigure 4-21.

Figure 4-19 Three-point pressure system is created by a splint’s surface and properly placed straps to secure the splint and ensure proper force for immobilization. [From Pedretti LW (ed.), (1996). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 336.]

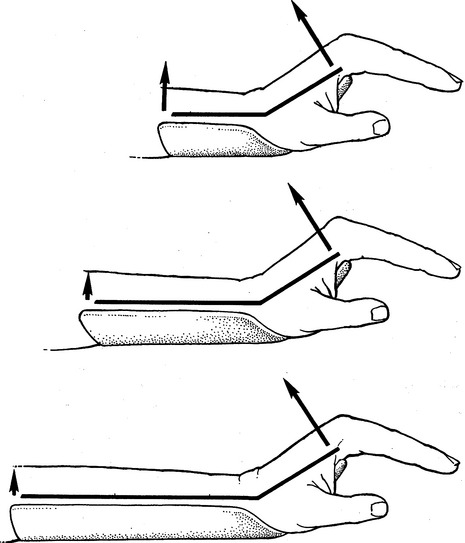

Mechanical Advantage

Splints incorporate lever systems, which incorporate forces, resistance, axes of motion, and moment arms. Splints serving as levers use a proximal input force (Fi), two moment arms, and an axis or fulcrum to move a distal output force [Fess 1995]. Similar to a teeter-totter, the force side of a splint lever equals the resistance side of the lever. The sum of the proximal (Fi) and the distal (Fo) forces equals the magnitude (Fm) of the middle opposing force. The system’s balance is defined as:

In this equation, Fi is the input force and di is the input distance (or the proximal force moment arm). Fo is the resistance (or output) force, and do is the output distance (or the resistance moment arm). Mechanical advantage is defined as:

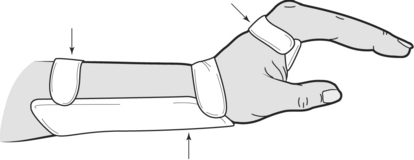

Mechanical advantage principles can be applied and adjusted when one is designing a splint. For example, when designing a volar-based wrist cock-up splint increasing the length of the forearm trough will decrease force on the proximal anterior forearm (Figure 4-22). This results in a more comfortable splint for the client. Application of this concept involves consideration of the anatomic segment length in designing the splint. The length of a splint’s forearm trough should be approximately two-thirds the length of the forearm. Persons wearing volar-based splints should be able to flex their elbows without interference with full motion [Barr and Swan 1988]. The width of a thumb or forearm trough should be half the circumference of the thumb or forearm. The muscle bulk of an extremity gradually increases more proximal to the body, and the splint trough should widen proportionately in the proximal area. When making a splint pattern, the therapist attempts to maintain one-half the circumference of the thumb or forearm for a correct fit.

Figure 4-22 A longer forearm trough decreases the resultant pressure caused by the proximally transferred weight of the hand to the anterior forearm. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Mechanical principles. In EE Fess, CA Philips (eds.), Hand Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 167.]

Torque

Torque is a biomechanical principle defined as the rotational effect of a mechanism. Other terms used synonymously include moment arm or moment of force. Torque is the product of the applied force (F) multiplied by the perpendicular distance from the axis of rotation to the line of application of force (d). The equation for torque is:

It is important to consider torque for dynamic or mobilization splinting (see Chapter 11).

Pressure and Stress

There are four ways in which skin and soft tissue can be damaged by force or pressure: (1) degree, (2) duration, (3) repetition, and (4) direction.

Degree and Duration of Stress

Generally, low stress can be tolerated for longer periods of time, whereas high stress over long periods of time will cause damage [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. It must be noted that low stress and high stress are generic and imprecise terms. A therapist should remember that generally the tissue that least tolerates pressure is the skin. Skin becomes ischemic as load increases. Low stress can be damaging if it is continuous and can eventually cause capillary damage and lead to ischemia. The effects of continuous low force from constricting circumferential bandages and splints and their straps can be damaging at times. However, if a system can be devised to distribute pressure over a larger area of skin a higher load can be exerted on a ligament, adhesion, tendon, or muscle. Such a splint system may include a longer trough or a circumferential component.

Repetitive Stress

If a stress is repetitively applied in moderate amounts, it can lead to inflammation and skin breakdown [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. An example of a repetitive stress may be seen in a person wearing a dynamic flexion splint that has rubber band traction. If the person continually flexes the finger against the tension, the tissue may become inflamed after some time. If inflammation or redness occurs, the therapist adjusts the tension by relaxing the traction. A therapist must realize that persons with traumatic hand injuries or pathology may not be able to tolerate the repetitive amounts of stress a normal person could tolerate. Poor tolerance is usually a result of damaged vascular and lymph structures.

High stress may quickly result in tissue damage [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. High stress can be applied to the skin from any object, such as a splint or bandage. The smaller or sharper the object the greater the amount of stress produced. High stress should be avoided at all times. For example, if a dynamic splint is applying too much stress to a joint, circulation may be restricted (potentially leading to tissue damage).

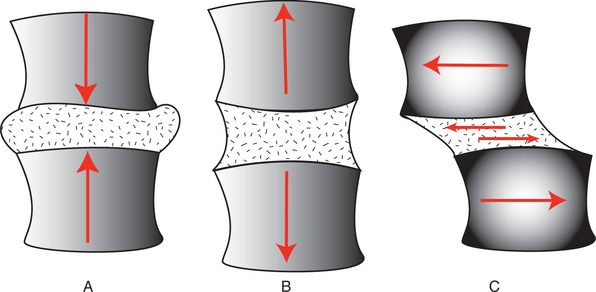

Direction of Stress

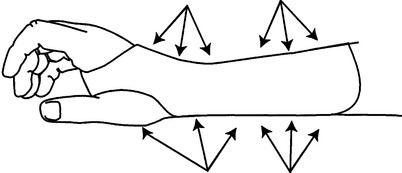

During splinting, consider the direction of stress or force on the skin and soft tissue. There are three directions of force to consider: (1) tension, (2) compression, and (3) shear [Fess 1995]. Tension occurs when forces on an object are applied opposite each other (Figure 4-23A). Compression stress results from forces pressing inwardly on an object (Figure 4-23B). Shear force occurs “when parallel forces are applied in an equal and opposite direction across opposite faces of a structure” [Fess 1995, p. 126] (Figure 4-23C). Research suggests that shear stress is the most damaging to skin [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995].

Figure 4-23 (A) Tension occurs when forces pull in opposite directions (tensile forces). (B) Compression is a force pushing tissues together. (C) Shear forces are parallel to the surfaces they affect. [From Greene DP, Roberts SL (2005). Kinesiology Movement in the Context of Activity, Second Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 21.]

Therapists must be astute in recognizing and knowing how to use the stress of splints in such a way as to not create soft-tissue damage. Generally, therapists avoid excessive stress or pressure from splints by employing wide troughs placed far from the fulcrum of movement while using an appropriate amount of tension on structures [Andrews and Bouvette 1996]. To determine the appropriate amount of tension on structures, the splint’s tension should be sufficient to take the joint to a comfortable joint end range. This means that the tension in the splint should bring the joint just to the maximum comfortable position (flexion, extension, deviation, or rotation) that is tolerable. This should be a position the client can tolerate for long periods of time. The client may need to work up to long wearing time, but the goal is usually at least four hours per day.

Ideally, the four hours will be continuous, but it can be broken up as necessary. Clients can be asked to try to wear their splints to improve passive range of motion (PROM) during sleep. However, this depends on their cognitive, sensory, and substance abuse status. The rationale for this wearing schedule is based on studies that show that low-load prolonged stress at the end range is very effective in increasing PROM. Technically, for dense scars or for tissue that has adaptively shortened over a long period of time higher tension forces can be used as long as the pressure is well distributed along the skin. The skin is the structure that is the “weak link.” The skin cannot tolerate the tension in the splint and becomes ischemic and therefore painful. If the pressure is well distributed, higher forces can be used and the tissue will lengthen more quickly as a result.

Several examples may explicate the effects of force on soft tissues [Fess 1995]. For example, after repair of a tendon rupture a therapist may employ early mobilization with a small amount of tension to facilitate the alignment of collagen fibers for improving tensile strength of the healing tendon. The tendon may be re-ruptured if the tension and repetition applied are not well controlled. A splint may be applied to assist in controlling fluctuating edema in the upper extremity. However, if the splint applies too much compression force on the underlying soft tissue over too much time the splint may restrict vascularity, possibly leading to soft-tissue necrosis. Shear stress between a healing tendon and its sheath must be carefully monitored to minimize and control adhesion shape.

The concepts of stress are considered when splinting. Splints and straps apply external forces on tissues that in turn affect forces or stresses exerted internally [Fess 1995]. The formula for pressure is:

Ideally, splints should be contoured and cover a large surface area to decrease pressure and the risk of pressure sores [Cannon et al. 1985]. Straps should be as wide as possible to distribute pressure appropriately and to prevent restriction of circulation or trapping of edema.

Thermoplastic splints can cause pressure points over areas with minimal soft tissue or over bony prominences. To avoid this risk, the therapist should use a splint design that is wider and longer [Fess et al. 2005]. A larger design is more comfortable because it decreases the force concentrated on the hand and arm by increasing the surface area of the splint’s force application.

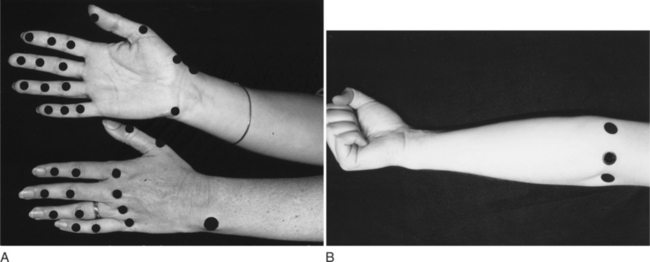

Continuous well-distributed pressure is the goal of a splint, but pressure over any bony prominence should be nonexistent [Cailliet 1994]. Therapists should be cautious of pressure over bony prominences, such as the radial and ulnar styloids and the dorsal-aspect MCPs and the PIPs (Figure 4-24). Therapists can use heat guns to alleviate pressure exerted by the splint. This is done by heating the plastic in problem areas and pushing the plastic away from the bony prominence. Another technique for avoiding pressure on bony prominences is to splint over padding, gel pads, or elastomer positioned over bony prominences. A frequent mistake in splinting occurs when a pad is placed over the localized pressure area after the splint is formed [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. Therapists should keep in mind that padding takes up space, reducing the circumference measurement of the splint and increasing the pressure over an area. Planning must be done before application of the thermoplastic material. The splint’s design must accommodate the thickness of the padding.

Figure 4-24 (A and B) Bony sites susceptible to pressure, which may cause soft-tissue damage. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Principles of fit. In EE Fess, CA Philips (eds.), Hand Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 261.]

Moist substances, such as perspiration and wound drainage, can cause skin maceration, irritation, and breakdown. Bandages help absorb the moisture but require frequent changing for infection control [Agency for Health Care Policy and Research 1992]. Some types of stockinette are more effective in wicking moisture away from skin. Polypropylene and thick terry liners are much more effective than cotton or common synthetic stockinette. Therapists can fabricate splints over extremities covered with stockinette or bandages, but the splint should be altered if the bulk of dressings or bandages changes.

Rolled or round edges on the proximal and distal ends of splints cause less pressure than straight edges [Cailliet 1994]. Imperfect edges are potential causes of pressure areas and therefore should be smoothed.

Contour

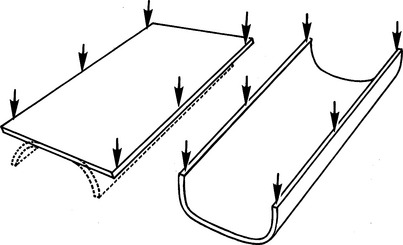

When flat, thermoplastic materials are more flexible and can be bent. Curving and contouring thermoplastic material to an underlying surface will change the mechanical characteristics of the material [Wilton 1997]. Contoured thermoplastic material is stronger and is better able to handle externally applied forces (Figure 4-25). Thermoplastic materials have varying degrees of drapability and conformity properties, which may affect the degree of contour the therapist is able to obtain in a splint.

Mechanics of Skin and Soft Tissue

Therapists often use splints to effect a change in the skin and soft tissue, which may address a client’s performance deficit. It is important to have a basic understanding of the mechanics of normal soft tissue and skin. In addition, one should know when and how the mechanics change in the presence of scar tissue, materials (bandages, splints, cuffs), edema, contractures, wounds, and infection.

Normal skin and soft tissue have properties of plasticity and viscoelasticity, which allow them to resist breakdown under stress in normal situations [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. Plasticity refers to the extent the skin can mold and reshape to different surfaces. Viscoelasticity refers the skin’s degree of viscosity and elasticity, which enables the skin to resist stress. The skin and soft tissue are able to tolerate some force or stress, but beyond a certain point the skin will break down [Yamada 1970].

When edema is present, the hand’s normal soft tissue undergoes mechanical changes because of the volume of viscous fluid present [Villeco et al. 2002, Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. Prolonged or excessive edema can lead to permanent deformity. Therefore, edema must be managed in conjunction with splint application. Splints often assist in controlling edema. Because of the increase in volume of fluid, swollen skin, joints, and tendons have an increase in friction in relation to the resistance to movement. “Swollen tissue, then, in addition to its increased viscosity, is limited in its ability to be elongated, compressed, or compliant. This is why a hand will never have a normal range of motion as long as there is edema in the tissue in and under the skin” [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995, p. 159].

Properties of thermoplastic material should be selected carefully. For example, soft splints with some flexibility and pliability may be more common in the future—once the properties of such materials are better understood [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. According to Schultz-Johnson [personal communication, March 3, 1999], soft splints may be limited in use for additional reasons. In Europe, high levels of immobilization are not deemed as valuable as they are in the United States. The limited use of soft splints may be related to philosophy of care, prior training, physician bias, and therapists’ habits.

Elastic bandages have the potential to apply high amounts of stress and may lead to constriction in the vascular and lymphatic circulation. A therapist must consider the amount of pressure applied to skin and tissue, especially when a second wrap of an elastic bandage covers an initial wrap. The pressure applied by the second wrap is doubled. This occurs even when bandages are applied in a figure-of-eight fashion. Another consideration is the effect bandages have on motion. Movement while bandages are being worn can further concentrate pressure, particularly over bony prominences. If appropriate, bandages should be removed while exercises are being performed.

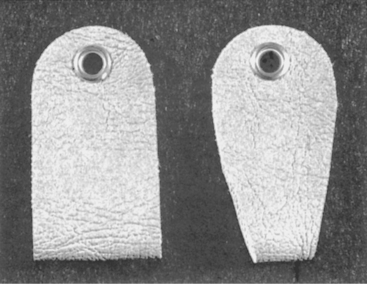

Finger cuffs or loops used with dynamic splinting increase pressure on the underlying skin and tissue. Bell-Krotoski et al. [1995] caution that using very flexible finger cuffs could increase the shear stress on fingers. Leather finger loops may be an appropriate choice because they simulate normal skin by being flexible while providing some firmness to decrease the shear stress. Finger loops should be as wide as possible to avoid edge shear and to distribute pressure (Figure 4-26). Chapter 11 addresses finger loops in more depth.

Figure 4-26 Finger loops apply pressure to the underlying surface. They should be as wide as possible without limiting adjacent joint mobility. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Principles of fit. In EE Fess, CA Philips (eds.), Hand Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 274.]

In joints with flexion contractures, skin on the dorsum of the joints grows with elongation tension on the skin [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995]. Skin on the volar surface of the joints is reabsorbed by a reduction in the elongation tension. There is a natural balance of tension in the skin and muscles. Skin will adjust to the tension required of it. Not only will skin lose length (contracture) but grow new cells to lengthen. The use of stretch gradually produces these changes. If skin is stretched to the point of microtrauma, a scar forms. When skin stretches, it releases proteins that result in scar formation. The scar tissue decreases the elasticity of the skin. To counteract excessive scarring, therapists use scar massage, mobilization techniques, and gentle stretch. Optimal regrowth involves the use of continuous (or almost continuous) tension [Bell-Krotoski et al. 1995].

New healing tissue can be negatively affected by mechanical stress. Tension of a wound site may “reduce the rate of repair, compromise tensile strength, and increase the final width of the scar” [Evans and McAuliffe 2002]. Rather than simply removing a splint and returning the extremity to function, Bell-Krotoski et al. [1995] suggested that immobilization splints should be gradually weaned as the affected skin and tissue become more mobile.

When working with a person who has infected tissues, caution must be taken to avoid mechanical stress from motion (as from a dynamic splint). Blood and interstitial fluids are forced into motion, and this pushes infection into deeper tissue and results in a more widespread infection and delay in healing. In the presence of infection, it is best to immobilize a joint with a splint for a few days and then remove the splint to maintain normal or partial range of motion.

Summary

A therapist’s knowledge of anatomic and biomechanical principles is important during the entire splinting process. One must be familiar with terminology to interpret medical reports, therapy prescriptions, and professional literature. In addition, the therapist uses medical terminology in documenting evaluation and treatment. The application of biomechanical principles to splint design and construction results in better fitting splints and thus contributes to compliance with therapeutic regimens. Ultimately, adherence to such principles impacts therapeutic outcomes.

1. To what do the terms palmar, dorsal, and radial (or ulnar) refer in regard to splint fabrication?

2. What are the three arches of the hand?

3. Why is support for the hand’s arches important when therapists splint a hand?

4. What is the significance of the distal palmar crease when therapists fabricate a hand splint?

5. If a splint’s edge does not extend beyond the thenar crease toward the thumb, what thumb motions can occur?

6. What is an example of each of the following prehensile or grasp patterns: fingertip prehension, palmar prehension, lateral prehension, cylindrical grasp, spherical grasp, hook grasp, and intrinsic plus grasp?

7. How can a therapist determine the correct length of a forearm splint?

8. What is the correct width for a splint that has a forearm or thumb trough?

9. What precautions should a therapist take when using padding on a splint?

10. What are two methods a therapist can use to prevent the edges of a splint from causing a pressure sore?

11. Why is it important to consider contour when fabricating a splint?

12. How do skin and soft-tissue mechanics change in the presence of scar tissue, material application, edema, contractures, wounds, and infection?

References

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Pressure ulcers in adults: Prediction and prevention (No. 92-0047). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1992.

Andrews, KL, Bouvette, KA. Anatomy for management and fitting of prosthetics and orthotics. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: State of the Art Reviews. 1996;10(3):489–507.

Aulicino, PL. Clinical examination of the hand. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Barr, NR, Swan, D. The Hand. Boston: Butterworth, 1988.

Belkin, J, English, CB. Hand splinting: Principles, practice, and decision making. In Pedretti LW, ed.: Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1996.

Bell-Krotoski, JA, Breger-Lee, DE, Beach, RB. Biomechanics and evaluation of the hand. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Bowers, WH, Tribuzi, SM. Functional anatomy. In: Stanely BG, Tribuzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1992.

Buck, WR. Human Gross Anatomy Lecture Guide. Erie, PA: Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, 1995.

Cailliet, R. Hand Pain and Impairment, Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1994.

Cailliet, R. Shoulder Pain, Second Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1981.

Cannon, NM, Foltz, RW, Koepfer, JM, Lauck, MF, Simpson, DM, Bromley, RS. Manual of Hand Splinting. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

Chase, RA. Anatomy and kinesiology of the hand. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Third Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Clarkson, HM, Gilewich, GB. Musculoskeletal Assessment: Joint Range of Motion and Manual Muscle Strength. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1989.

Colditz, JC, McGrouther, DA. Interactive Hand: Therapy Edition CD-ROM. London: Primal Pictures, 1998.

Evans, RB, McAuliffe, JA. Wound classification and management. In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman L, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Fess, EE. Splints: Mechanics versus convention. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1995;9(1):124–130.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

Kapandji, IA. The Physiology of the Joints. London: E&S Livingstone, 1970.

Kleinert, HE, Schepel, S, Gill, T. Flexor tendon injuries. Surgical Clinics of North America. 1981;61(2):267–286.

Long, C, Conrad, PW, Hall, EA. Intrinsic-extrinsic muscle control of the hand in power grip and precision handling: An electromyographic study. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery. 1970;52:853.

Malick, MH. Manual on Static Hand Splinting. Pittsburgh: Hamarville Rehabilitation Center, 1972.

Pedretti, LW. Hand splinting. In: Pedretti LW, Zoltan B, eds. Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction. Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1990:18–39.

Smith, LK, Weiss, EL, Lehmkuhl, LD. Brunnstrom’s Clinical Kinesiology, Fifth Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1996.

Villeco, JP, Mackin, EJ, Hunter, JM. Edema: Therapist’s management. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremities. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:183–193.

Wilton, JC. Hand Splinting Principles of Design and Fabrication. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1997.

Wu, PBJ. Functional anatomy of the upper extremity. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: State of the Art Reviews. 1996;10(3):587–600.

Yamada, H. Strength of Biological Materials. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1970.