Mobilization Splints: Dynamic, Serial-Static, and Static Progressive Splinting

1 Understand the biomechanics of dynamic splinting.

2 Identify effects of force on soft tissue.

3 Understand the way to apply appropriate tension.

4 Identify common uses of dynamic splinting.

5 List the goals of dynamic splinting.

6 List the materials necessary for fabrication of a dynamic splint.

7 Explain the risks of applying dynamic force.

8 Identify contraindications for application of a dynamic splint.

9 Understand the fabrication steps of three dynamic splints.

10 Identify instances in which dynamic splinting is appropriate.

Mobilization splints or dynamic splints have movable parts and are designed to apply force across joints [Brand 2002]. Mobilization splints use constant or adjustable tension, or both, to achieve one of the following goals [Fess 2002]:

• Substitute for loss of muscle function

• Correct deformities caused by muscle-tendon tightness or joint contractures

• Maintain active or passive range of motion

• Provide controlled motion after tendon repair or joint arthroplasty

This chapter provides basic information on the principles of dynamic splinting. Specifically, this chapter reviews the construction process of dynamic splints for a flexor tendon repair, radial nerve injury, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion contracture. Even though early attempts at dynamic splint construction may seem challenging, the process becomes easier with practice and experience.

Implications of Mobilization Splints

There are many implications for the use of dynamic splinting that become more familiar to the therapist with increased exposure to various hand injuries. Some specific indications for the use of dynamic splints are presented in this chapter. However, it is important to note that the therapist must first understand the person’s injury, surgical procedures, and physician’s protocol for treatment. If any of these conditions are in question, the therapist should seek clarification prior to splinting.

Substitution for Loss of Motor Function

Whether the person has a peripheral nerve injury, spinal cord injury, or other debilitating disease, a splint can increase the functional use of a hand. The goals of splinting for loss of muscle function are to substitute for loss of motor use, prevent overstretching of nonfunctioning muscles, and prevent joint deformity. Both dynamic and static splints can accomplish these goals [Fess et al. 2005].

A common peripheral nerve injury is high radial nerve palsy. A hand with radial nerve damage has limited functional use due to the inability to extend the wrist and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and because of the lack of palmar abduction and radial abduction of the thumb. A splint that provides passive assistance to the wrist and MCP joints in extension while allowing active composite flexion of the fingers will greatly increase the functional use of the hand (see also Chapter 13,Figure 13-8).

Another example of substitution for loss of motor function involves persons with spinal cord injuries. A person who has a C7 lesion may also benefit from dynamic splinting. The person’s active wrist extension will become the force to transmit motion for finger flexion in a tenodesis splint (Figure 11-1).

Finally, persons who have debilitating diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Guillain-Barrè syndrome, or other neurologic disorders may benefit from specialized dynamic splints. However, the presence of spasticity might preclude candidates for dynamic splinting (see Chapter 14).

Correction of a Joint Deformity

Limited passive joint range of motion might be a result of multiple factors, including prolonged immobilization, trauma, or significant scar formation. A person who exhibits limited passive joint motion may be a candidate for a dynamic splint. However, if a large discrepancy exists between active and passive joint motion the goal of treatment should focus on active range of motion and strengthening prior to splinting. If active range of motion and passive range of motion are similar, greater active motion can be gained through mobilization splinting [Colditz 2002a].

The best results from dynamic splinting are attained when the therapist initiates treatment soon after edema and pain are under control. As mentioned previously in this text, the best way to lengthen tissue is to provide a tolerable force over a long period of time. Research indicates a direct correlation between the length of time a stiff joint is held at its end range and the resulting gain achieved with passive joint motion [Flowers and LaStayo 1994]. The focus of dynamic splinting should be on increasing the length of time the splint is worn rather than increasing the force. However, certain conditions (such as dense ligaments or scar tissue) generally always require a greater amount of force to achieve tissue remodeling.

Application of external force necessitates careful attention to the distribution of pressures over the skin surface because the skin is always the weak link in the system. A general goal for a mobilization splint is to increase passive joint range of motion by 10 degrees per week [Brand 2002]. Should passive range of motion not improve following two weeks of splinting, the splinting and treatment program should be reevaluated [Fess and McCollum 1998].

Provision of Controlled Motion

Therapists use dynamic splinting to control motion after the completion of joint implant arthroplasty and flexor tendon repairs. Because of the altered joint mechanics of a person who has arthritis and undergoes joint replacement surgery, the dynamic splint has multiple functions. First, dynamic splints provide controlled motion and precise alignment of the repaired soft tissue while minimizing soft-tissue deformity. For example, after joint replacement the splint may provide forces on one finger in both extension and radial deviation. Second, the splint maintains alignment of the joints for the healing structures while allowing guarded movement of the joint [Fess et al. 2005].

After flexor tendon repairs, the therapist uses a dynamic splint to provide controlled motion to the healing structures. The reasons for controlled motion are threefold. First, moving the tendons increases the flow of nutrient-rich synovial fluid to enhance healing. Second, tendons allowed early mobilization have demonstrated increased tensile strength compared to immobile tendons. Third, by allowing 3 to 5 mm of tendon excursion adhesion formation between tendons and surrounding structures is minimized [Stewart and van Strien 2002].

Aid in Fracture Alignment and Wound Healing

Dynamic traction should be used for the treatment of selected intra-articular fractures of the finger [Hardy 2004]. A dynamic traction splint involves the use of static tension while allowing joint movement. Traction provides tension to the ligaments, which incorporates the use of ligamentotaxis to bring boney fragments back into anatomic alignment. With constant traction applied throughout the range of motion, the splint allows the fracture to heal while maintaining adequate glide of surrounding soft tissues. Mobilization splints may also be used following a severe burn to assist in wound healing. The use of such splinting during wound healing will facilitate proper collagen alignment and scar formation.

Biomechanics of Dynamic Splinting

To fabricate a dynamic splint accurately, a therapist must understand the principles of hand biomechanics and must know in what ways the application of external force affects normal hand function [Fess 2002]. Knowledge of complex mathematical calculations is not required for a therapist to have a basic understanding of the biomechanics of dynamic splinting.

The goal of a mobilization splint is to restore a joint’s normal range of motion, and to minimize the effects of inflammation and scar tissue. Application of an external force to healing joint structures raises the following questions. During what stage in the healing process should a splint be used to apply force? How much force should the splint apply? Where should the force be applied? The therapist should exercise caution when applying force to an injured joint until the inflammation and pain are under control. Mild inflammation is acceptable, but edema should not fluctuate significantly. A mobilization splint applied too early after injury might result in increased inflammation and decreased motion.

Soft-tissue structures respond to prolonged stress by changing or reforming. This activity is called creep and results from the application of prolonged force [Brand and Hollister 1993b]. Soft tissue responds to excessive force with increased pain and a reintroduction of the inflammatory process [Fess and McCollum 1998]. By applying controlled stress to the tissue over a prolonged period of time, the therapist can create tension gentle enough to allow creep without tissue injury. Provided it remains within elastic limits, the stress from a mobilization splint can positively affect the gradual realignment of collagen fibers (resulting in increased tensile strength of the tissue) without causing microscopic tearing of the tissue. The ability to alter collagen formation is greatest during the proliferative stage of wound healing but continues to a lesser degree for several months during scar maturation [Colditz 2002].

Torque and Mechanical Advantage

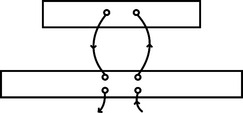

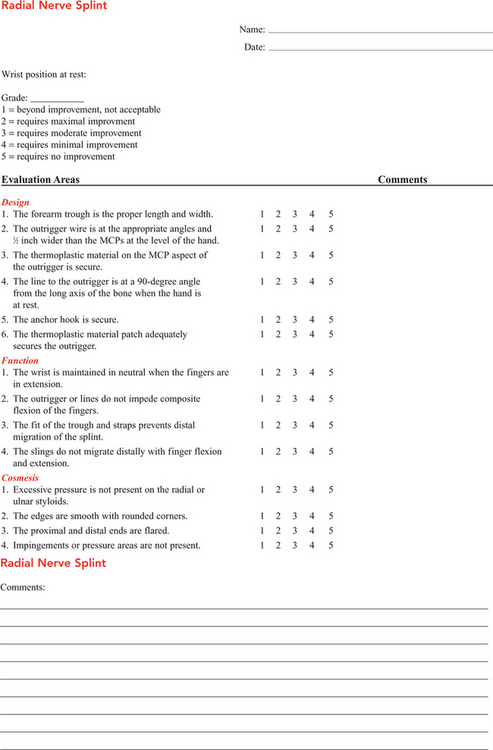

To provide the greatest benefit from a mobilizing splint, the therapist must understand relevant theories of physics. Mechanical advantage involves the consideration of various forces applied by the splint base and the dynamic portion of the splint. As seen inFigure 11-2, Fa refers to the applied force and Fr refers to the resistance force. Fm is determined by the sum of the opposing forces (Fa+ Fr) [Fess 1995]. Mechanical advantage is defined as [Brand 2002]:

By adjusting the length of the splint base or the length of the outrigger, the mechanical advantage can be altered (Figure 11-2) [Smith et al. 1996]. The goal of a splint is to maintain a mechanical advantage of between 2/1 and 5/1, meaning that the lever arm of the applied force is at least twice as long as the lever arm of the applied resistance [Brand 2002]. A splint with a greater mechanical advantage will be more comfortable and durable [Fess 1995]. A mobilizing MCP flexion splint that is forearm and hand based rather than just hand based will disperse pressures in addition to providing a greater mechanical advantage due to the longer lever areas of the applied force.

Figure 11-2 Mechanical advantage is determined by the ratio of the lever arm length (la) of the applied force (Fa) to the lever arm (lr) of the applied resistance (Fr). Splint A has a better mechanical advantage than splint B.

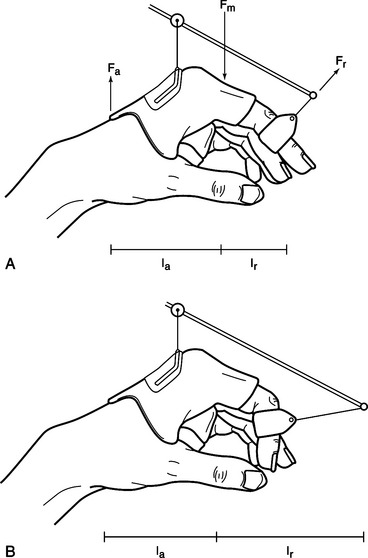

Torque is defined as the effect of force on the rotational movement of a point [Fess et al. 2005]. The amount of torque is calculated by multiplying the applied force by the length of the moment arm (Figure 11-3). A correlation exists between the distance from a pivot point and the amount of force required. To achieve the same results, a force applied close to the pivot point (i.e., short moment arm) must be greater than the force applied on a longer moment arm. This force is called torque because it acts on the rotational movement of a joint.

Figure 11-3 The 2-inch moment arm produces 24 inch ounces of torque. The 3-inch moment arm produces 36 inch ounces of torque.

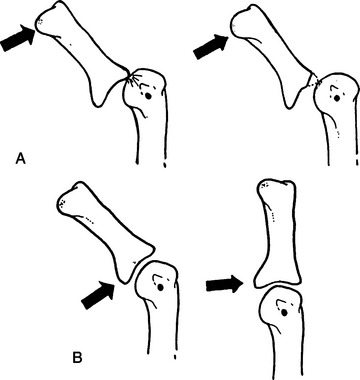

In practical terms, the therapist should place the force as far as possible from the mobilized joint without affecting other joints [Brand and Hollister 1993b]. A forearm-based dynamic wrist extension splint should be constructed so that its mobilizing force is on the most distal aspect of the palm, while not affecting MCP movement. An exception to placing the force as far from the mobilized joint as possible occurs when rheumatoid arthritis is involved. If the joint is unstable, a force applied too far from the joint will result in tilt rather than a gliding motion of the joint (Figure 11-4) [Hollister and Giurintano 1993]. Therefore, when splinting a hand with rheumatoid arthritis the force should be applied as close to the mobilizing joint as possible.

Application of Force

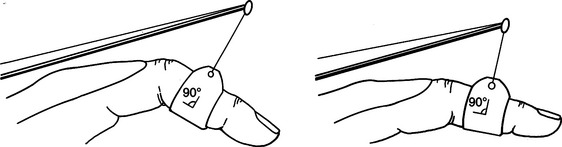

In dynamic splinting, the therapist applies force to a joint or finger through the application of nail hooks, finger loops, or a palmar bar. When applying force to increase passive joint range of motion, the therapist must keep the direction of pull at a 90-degree angle to the axis of the joint and perpendicular to the axes of rotation [Cannon et al. 1985]. As range of motion increases, the therapist must adjust the outrigger to maintain the 90-degree angle (Figure 11-5) [Fess et al. 2005]. The outrigger should not pull the finger or hand toward ulnar or radial deviation.

When excessive force is applied to the skin for a prolonged period, tissue damage can result. The amount of pressure the skin can tolerate dictates the maximum tolerable force. As a general rule, the amount of acceptable pressure or force per unit area is 50 g/cm2 [Brand and Hollister 1993a]. As the area over which force is applied becomes larger, the pressure per unit area becomes less. A leather sling with a skin contact area on a finger of approximately 4 cm2 should provide a maximum pressure of 200 g [Fess at al. 2005]. A smaller sling with less skin contact area concentrates the pressure and is less tolerable.

Skin grafts, immature scar tissue, and fragile skin of older persons have less tolerance for sling pressure. The person’s tolerance ultimately determines the amount of force. The person should report the sensation of a gentle stretch, not pain [Fess 2002]. To avoid harm, the therapist should monitor the splint for the first 20 to 30 minutes of wear and at every treatment session thereafter. The person must also be educated on the importance of monitoring the splint for signs of pressure areas and skin breakdown, as well as how to don and doff the splint properly.

Features of a Mobilization Splint

Two features unique to mobilization splinting are the use of an outrigger and the application of force. The outrigger is a projection from the splint base the therapist uses to position a mobilizing force. The outrigger material depends on the amount and position of the desired force. If the outrigger and attachment to the base are not secure, the direction of the mobilizing force may change—reducing the effectiveness of the splint [Colditz 1983].

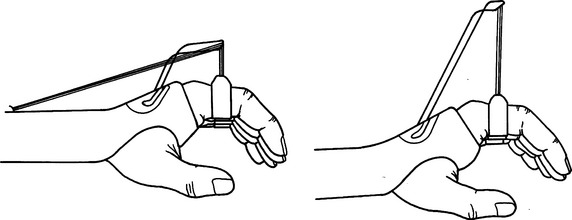

An outrigger can be a high or low profile (Figure 11-6). Each type has advantages and disadvantages. With a significant change in range of motion, the high-profile outrigger will result in slightly less deviation from the 90-degree angle of pull than the low-profile outrigger. Clients should be seen in the clinic frequently enough that increases in range of motion can be accommodated by regular adjustments to the outrigger, thus maintaining the 90-degree angle of pull [Austin et al. 2004]. It should be noted that a high-profile outrigger, on the other hand, is bulky and may decrease the person’s compliance with wearing the splint. A low-profile outrigger requires adjustments more frequently but is more aesthetically pleasing and less cumbersome.

Various materials might be used for outriggers. The therapist may roll a thermoplastic material that has a high level of self-adherence to form a thick, tubular outrigger. This material offers easy adjustment by reshaping the plastic. However, a thermoplastic material outrigger may make the splint more cumbersome and thus reduce the person’s compliance with the wearing schedule. There are also commercially available low-temperature tubes that are easily formed and less cumbersome.

A therapist can form an outrigger from  -inch wire rod. This diameter is thick enough to provide stability yet pliable enough to manipulate with pliers. Construction of an outrigger using a wire rod requires precise shaping, a skill that necessitates practice. Commercial adjustable wire outrigger kits are also available. Although the use of a commercial kit may increase the material cost of the splint, the application of the adjustable components is easier and may thus reduce splintmaking time. The therapist should bear in mind that charges for fabrication time are the most costly part of the splint.

-inch wire rod. This diameter is thick enough to provide stability yet pliable enough to manipulate with pliers. Construction of an outrigger using a wire rod requires precise shaping, a skill that necessitates practice. Commercial adjustable wire outrigger kits are also available. Although the use of a commercial kit may increase the material cost of the splint, the application of the adjustable components is easier and may thus reduce splintmaking time. The therapist should bear in mind that charges for fabrication time are the most costly part of the splint.

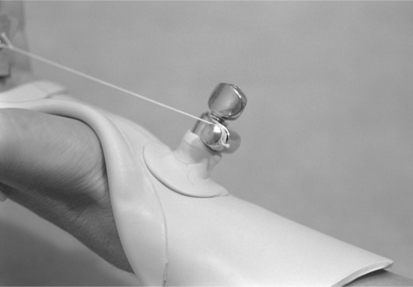

The therapist can use various methods for applying dynamic force to a joint. Finger loops from strong pliable material are usually best because of the increased conformability to the shape of the finger [Fess et al. 2005]. The therapist can supply force by using rubber bands, springs, or elastic thread. Although rubber bands are more readily available and easy to adjust, springs offer more consistent tension throughout the range. A long rubber band stretched over the maximum length of the splint provides more constant tension than a short rubber band [Brand and Hollister 1993a]. Elastic thread is the easiest to apply and adjust. A nonstretchable string or outrigger line is necessary to connect the finger loop to the source of the force (Figure 11-7). The choice is usually based on clinical experience and preference.

Figure 11-7 The therapist uses nonstretchable nylon string to attach finger loops to the source of tension.

Another method of applying force is through static progressive tension. Rather than providing the variable tension of a dynamic splint, a static tension splint uses nonelastic tension to provide a constant force. An advantage of properly applied static tension is that tissue is not stretched beyond the elastic limit [Schultz-Johnson 2002]. In place of the rubber band or spring (as used on a dynamic tension splint) the therapist may use a Velcro tab, turnbuckle, or commercially available static progressive components to apply the force (Figure 11-8). Tension is increased by gradually moving the Velcro tab more proximally on the splint base or adjusting the turnbuckle. The force is static rather than dynamic but is readily adjustable by the person throughout the wearing time (Figure 11-9). Because the person has control over the amount of applied tension, the static progressive splint is more tolerable to wear than a dynamic tension splint [Schultz-Johnson 2002].

In determining whether to apply dynamic or static tension, the therapist must identify the “end feel” of a joint. End feel is assessed by passively moving a joint to its maximal end range. A joint with a soft or springy end feel indicates immature scar tissue. A joint with a hard end feel indicates a more mature scar tissue or long-standing contracture. A splint with static or dynamic tension is appropriate for a joint with a soft end feel, whereas a joint with a hard end feel will respond only to static tension. Regardless of the end feel, static tension will increase passive range of motion faster than dynamic tension for any joint [Schultz-Johnson 1996].

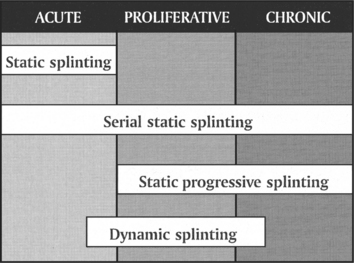

Another determinant in selecting the type of tension to be used with mobilization splinting is the stage of tissue healing. As seen inFigure 11-10, different types of splints are more appropriate at various stages of healing. The acute stage is primarily characterized as the initial inflammatory stage. The proliferative stage occurs after the initial inflammation subsides and tissues are in the early stages of reorganization. The chronic stage is attained when the cells have realigned and the joint response to stress is a hard end feel [Colditz 1995].

Technical Tips for Dynamic Splinting

When applying an outrigger to the base, the therapist must ensure that both surfaces to be bonded are clean. If a plastic has a glossy finish, the two surfaces might require light scratching or a bonding agent to increase self-adherence. After placing the outrigger on the base appropriately, the therapist should hold the surfaces firmly together and smooth the edges until the plastic cools. To speed hardening, a vapocoolant spray may be used.

The therapist should use caution when spot heating near an outrigger wire. Wire conducts heat more greatly than plastic, and thus the wire may push through the thermoplastic material. When splinting over bandages or a dressing, the therapist may place a damp paper towel or stockinette over the area to prevent the thermoplastic material from adhering to the dressing. The therapist should check the line of pull so that a 90-degree angle is present on the finger loops when axial and lateral views are observed. Finally, all joints should be checked from various angles to ensure that joints are not being pulled into hyperextension, ulnar deviation, or radial deviation.

Materials and Equipment for a Dynamic Splint

In addition to the equipment necessary to fabricate a static splint, a variety of items are required to fabricate a dynamic splint. The following is a list of materials and equipment therapists use for dynamic splinting, although all items are not necessary for every splint.

• Thermoplastic material with a high level of self-adhesion

• Nail hooks, an emery board, and super-glue

• Nonstretchable nylon string (outrigger line)

• A wire rod ( inch) with tools to bend

inch) with tools to bend

• Rubber bands, springs, elastic string, Velcro tabs, turnbuckles, or commercially available static progressive components

Mobilization splinting can be both fun and challenging. Three common mobilization splints include the flexor tendon splint, the mobilization PIP extension splint, and the radial palsy splint. These are described in the sections that follow.

Fabrication of a Flexor Tendon Splint

One common use of a dynamic splint is for a person who has an injury to one or more finger flexor tendons. The goals of postoperative flexor tendon repair are to [Loth and Wadsworth 1998]:

The splint assists in attaining these goals by maintaining the hand in a protected position while allowing controlled motion of the fingers [May et al. 1992]. This type of dynamic splint is one of the least complicated to fabricate because an outrigger is not required. However, it is a very demanding splint because initially it must be worn 24 hours per day (with removal only for therapy). Therefore, the fit must be very good to ensure comfort and to prevent migration of the splint. The therapist should also check the physician’s preference in regard to the type of splint and wearing schedule because various protocols exist for tendon repairs. Although no protocol is universally accepted, two of the most common are the Kleinert [1983] and the Duran and Houser [1975] [Stewart and van Strien 2002]. The following splint is a modification of both protocols:

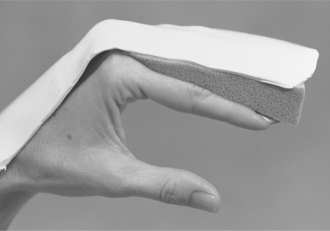

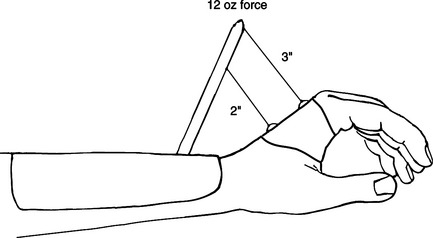

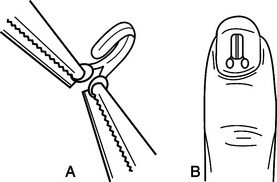

1. Apply the nail hooks to the person’s fingernails so that the super-glue thoroughly dries before application of the force. Explain to the person the reason for the application of the hooks, and assure the person that removal of the hooks is possible. To increase the adherence of the hook, roughen the fingernail with an emery board and then clean the fingernail with an alcohol wipe. The hook may require an adjustment with two pairs of pliers to fit the contour of the nail (Figure 11-11A). Position the hooks so that they face the person. Hooks should be applied to the proximal nail bed to prevent avulsion of the fingernail (Figure 11-11B). When applying the hook, do not use on an excessive amount of glue. Glue that comes in a gel form may be easier to manage. Give the person extra hooks and application instructions because hooks may occasionally break off. Alternatives to the nail hooks are adhesive Velcro loop applied to the nail and sutures placed through physician-created holes in the nail during surgery.

Figure 11-11 (A) Pliers may be used to adjust the hook to fit the contour of the fingernail. (B) The nail hook is applied to the proximal nail bed.

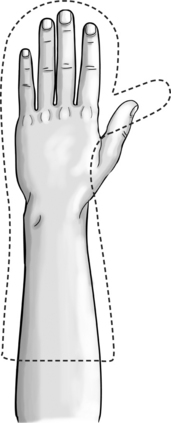

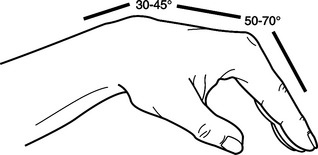

2. Construct the pattern for a dorsal hand and forearm splint, similar to that shown inFigure 11-12. Select thermoplastic material with a property of drapability. Remember to design the pattern to cover two-thirds the length of the forearm and half the circumference of the forearm. The distal end of the splint should extend about 1 inch beyond the tips of the fingers. Form the splint base over the dorsal surface of the forearm, wrist, and hand while molding the palmar bar. The ideal hand position is 30 to 45 degrees of wrist flexion, 50 to 70 degrees of MCP flexion, and the interphalangeals (IPs) in full extension [May et al. 1992] (Figure 11-13). If the hand has just been removed from the postoperative bulky dressing, the person may not tolerate the ideal position. If this occurs, splint as close as possible to the ideal position and adjust the splint when tolerable. Plastics with memory are helpful in reforming the splint’s positions.

Figure 11-13 The ideal position after flexor tendon repair is 30 to 45 degrees of wrist flexion, 50 to 70 degrees of metacarpal phalangeal flexion, and full interphalangeal extension.

3. Use a heat gun to create a bubble over the radial styloid and distal ulna to avoid pressure, or pad the bony prominence.

4. Apply straps with hook-and-loop Velcro at the following locations: across the palmar bar, at the wrist, 3 inches proximal to the wrist, and across the forearm (Figure 11-14).

Figure 11-14 Straps are applied across the palmar bar, at the wrist, 3 inches proximal to the wrist, and at the forearm. The safety pin is fixed to the strap 3 inches proximal to the wrist crease.

5. Attach a safety pin to the strap that crosses the wrist approximately 3 inches proximal to the wrist crease (seeFigure 11-14).

6. Apply traction using elastic thread attached to the nail hooks at the distal end and to the safety pin at the proximal end. Use elastic thread due to its ability to stretch while maintaining a fairly constant tension. Apply the force to hold the fingers in flexion, but allow the person to achieve full active extension of the IP joints against the force of the elastic (Figure 11-15). It may take a few days before full IP extension is attained if the client had been immobilized previously with the fingers flexed. As IP extension improves, adjust the splint elastic tension to maintain passive finger flexion while allowing full active extension.

Achieving full PIP and distal IP extension is important because flexion contractures are a common complication following flexor tendon repair [Jebson and Kasdan 1998]. If the person is unable to attain full PIP extension, a wedge may be placed behind the involved finger(s). The purpose of the wedge is to increase MCP flexion, thus decreasing flexor tension and increasing PIP extension (Figure 11-16).

Zone II Flexor Tendon Repairs

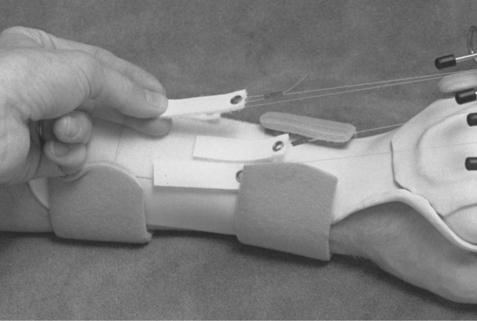

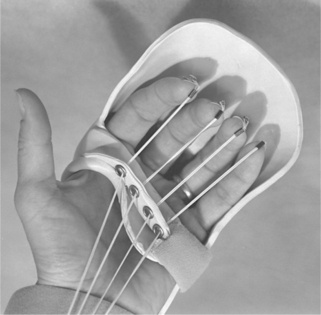

Due to the confined arrangement of tendons within the pulley system, flexor tendon injuries in zone II are highly susceptible to adhesions (Figure 11-17) [Duran et al. 1990]. A palmar pulley might provide greater excursion of tendons from these lesions. This pulley can be created by firmly securing an additional piece of thermoplastic with eyelets for each finger (Figure 11-18). The palmar bar also serves to maintain the palmar arch and prevents splint migration. The elastic thread runs through the palmar pulley as the person actively performs approximately 10 repetitions of active finger extension every hour. The treatment rationale is to increase excursion of the tendon, limit scar formation, and increase tensile strength of the repair [May et al. 1992].

Figure 11-18 An attachment may be added to the palmar bar to increase tendon excursion in zone II injuries.

The therapist may apply a strap to the distal aspect of the fingers in order to maintain full IP extension (Figure 11-19). This application may also reduce the loss of extension at the IP joints [May et al. 1992]. Generally, the strap is intended only for night wear—traction being maintained throughout the day. If, however, the person has developed or is developing an IP flexion contracture the person may alternate between flexion traction and the extension strap during the day. The therapist should issue the person a written home program consisting of a splint-wearing schedule, instructions regarding splint care, and therapeutic exercises.

Fabrication of a Mobilizing PIP Extension Splint

The PIP joint is the most important joint of the finger with regard to functional hand use. A PIP joint that cannot fully extend limits the ability of the hand to grasp large objects, inhibits the person’s ability to place a hand in a pocket, and hinders other functional activities [Prosser 1996]. A mobilizing PIP extension splint is designed to help regain limited passive extension of the PIP joint. A loss of PIP extension may occur following soft-tissue damage at the PIP joint; crush injury, burn, or fracture around the PIP joint; or flexor tendon repair. There are many splint options to regain PIP motion, including both custom-fit and prefabricated splints.

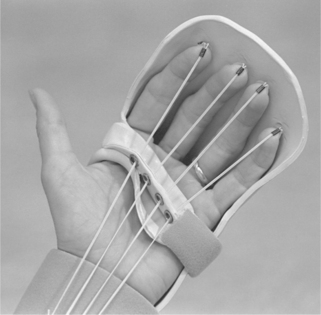

For a custom-fit splint, an outrigger kit with extender rods is practical to use due to the ease of adjustment as the person’s range of motion increases. The commercial outrigger usually contains a wire outrigger, extender rod, Allen wrench, rubber cap for the rod, and adjustment wheel to secure the rods to the outrigger. This PIP extension splint is hand based in order to prevent immobilization of the non-involved wrist joint. Instead of springs or Velcro tabs, the therapist uses a rubber band to provide a dynamic progressive force. Multiple-finger outrigger kits are also available for this type of splint (Figure 11-20). The following are instructions for creating a hand-based splint.

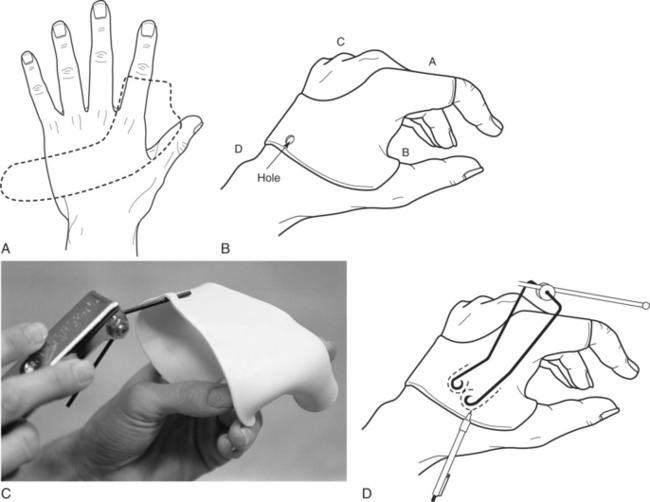

1. Fabricate a pattern for a hand-based splint. The splint is primarily dorsally based, with the MCP joint of the involved finger immobilized (Figure 11-21A). A thermoplastic material that has high drapability is the most appropriate for this splint. As the splint is conformed to the person’s hand, maintain a 45-degree angle of MCP flexion while molding the splint around the proximal phalanx and the first web space. If necessary, the ulnar bar may be reheated later and conformed to the ulnar aspect and palm of the hand. The following is a checklist for the splint base (letters in parentheses correspond to those inFigure 11-21B).

Figure 11-21 (A) Splint pattern for a hand-based PIP extension splint. (B) Splint base checklist. (C) An Allen wrench or other small tool may be used to raise the edge of the splint to form a site for attachment of the elastic tension. (D) With the extender rod appropriately positioned above the finger, the therapist draws an outline of the outrigger on the splint base.

• The distal aspect of the splint must be proximal to the PIP joint in order to allow unrestricted motion (A).

• At the first web space, the splint should not limit thumb opposition (B). This edge of the splint may be rolled if necessary.

• MCP extension of non-involved fingers should not be limited (C).

• Wrist motion should not be limited by the proximal aspect of the splint (D).

2. Remove the splint from the person. Using a leather punch, make a small hole in the dorsal ulnar aspect of the splint (Figure 11-21B). Using the heat gun, warm the area around the hole. With an Allen wrench, lift the area (Figure 11-21C) to form a site for later attachment of the rubber band. The rubber band may also be attached using and adhesive strap with a D-ring.

3. Reapply the splint to the person. Attach the outrigger as follows:

a. With the adjustment wheel and extender rod loosely attached to the outrigger, position the outrigger on the splint so that the rod is parallel to and centered on the proximal phalanx.

b. With the outrigger in place, mark the splint where the ends of the wire are to be attached to the base (Figure 11-21D).

4. Remove the splint from the person. If the extender rod is in the way, remove it before attaching the outrigger to the base.

5. Cut a piece of thermoplastic material large enough to extend beyond the outrigger base by at least ½ inch on each side.

6. Heat the outrigger wire over a heat gun, and slightly embed the wire into the splint base.

7. Lightly scratch the surface or apply solvent to the warm piece of thermoplastic material to increase the bonding.

8. Place the warm thermoplastic material over the outrigger base, and secure the material to the splint base by pressing the material securely around the outrigger wire.

9. Loosely reattach the extender rod to the outrigger.

10. Apply the splint to the person’s hand.

11. If a prefabricated finger loop is not available, one can be made using soft leather or polyethylene. A sling that is 4 inches long and 1 inch wide will be appropriate for most adult fingers. Holes are punched at the two ends of the sling for the line attachment. The long edges may need slight trimming so that the sling does not interfere with movement of non-involved joints. With the loop in place on the middle phalanx and nylon string placed through the rod, position the extender rod to obtain a 90-degree angle of pull (Figure 11-22A). Gently tighten the rods in place using the Allen wrench.

Figure 11-22 (A) The extender rod is adjusted to provide a 90-degree angle of pull on the middle phalanx. (B) A rubber band or elastic thread is attached to nylon string and adjusted to provide appropriate tension.

12. Secure the appropriate rubber band to the nylon string so that the tension pulls the joint to a well-tolerated end range (Figure 11-22B).

13. Remove the splint from the person and finish securing the extender rod. If the rods extend more than ½ inch proximal to the adjustment wheels, the rod may be cut using heavy-duty wire cutters. For safety reasons, snip the excess extender rod when the person is not wearing the splint.

Fabrication of a Composite Finger Flexion Splint with Static Progressive Tension

Following trauma to the wrist or hand, a person may often experience joint pain or stiffness that limits the ability to attain composite finger flexion. Whereas therapy will focus on restoring joint range of motion of the individual joints in addition to composite finger flexion, a splint that focuses on providing a low-load prolonged stress to all of the joints will maximize the return of function. This splint uses static progressive tension to allow the person to control the amount of force required to maintain the tissue at a maximum tolerable stretch [Schultz-Johnson 2002]. Although a custom-made component will be utilized for this splint, a commercially available “Bio-dynamic” component for finger sleeves is available through Smith-Nephew, Roylan.

1. Fabricate a volar-based wrist immobilization splint with straps as directed in Chapter 7. Ensure that the distal aspect of the splint does not limit MCP flexion of the index through small fingers.

2. With the splint applied to the person, mark on the distal palmar bar where the fingers would touch with full composite finger flexion (Figure 11-23A). Remove the splint from the person.

Figure 11-23 A mark is applied to the palmar bar at the point where each finger achieves composite flexion.

3. A line guide for the monofilament will be created using a metal non rubber-coated paper clip. Using wire cutters, snip a section of the paper clip to form a ?-inch loop. With pliers, bend at the midsection to form a 90-degree angle (Figure 11-24).

4. Grasping the bent paper clip with a pair of pliers, hold over a heat gun for approximately 10 seconds. Carefully insert the metal clip into the rolled aspect of the palmar bar where previously marked (Figure 11-25).

Figure 11-25 Using pliers, the open end of the heated wire is pushed through the distal aspect of the palmar bar where previously marked.

5. For each finger to be included in the splint, two finger sleeves will be required: one for the proximal phalanx and one for the distal phalanx. Cut two ¾-inch by 3-inch pieces of Velfoam or other similar hook-and-loop material for each finger.

6. On the proximal sleeve, punch four (4) small holes at the midpoint and on the distal sleeve punch two small holes at the midpoint. As inFigure 11-26, the monofilament thread or other suitable material is threaded through the proximal sleeve to the distal sleeve and returning to the proximal sleeve.

7. Following reapplication of the thermoplastic splint, the finger sleeves are secured on the proximal and distal phalanges with a piece of Velcro hook. The monofilament pulley line will be located at the midpoint on the volar aspect of the finger. Note that the finger sleeve may need to be trimmed for a secure fit.

8. The long ends of the monofilament are threaded through the metal line guide.

9. While applying light tension to the finger sleeves, secure a Velcro hook tab to the end of the monofilament thread. Be sure to secure the tab on the distal end of the Velcro loop strip so as to allow improvements in range of motion without having to make further adjustments.

10. The person is then asked to secure the Velcro tab at a place that provides a gentle stretch to the finger(s). After 5 to 10 minutes of wearing the splint, the person may be able to increase the amount of tension. A mark may be placed on the Velcro loop where the tab is located in order for the person to note improvements as progress is made in range of motion and the tab is moved more proximally (Figure 11-27).

Finger Flexion Splint Wearing Schedule

Initially the person is instructed to wear the splint for 30 minutes three to four times per day. If there are no complications, the splint wear time can be increased significantly. The static progressive splint may be worn for extended periods of time because the person can control the amount of tension. Some people may tolerate wearing the splint at night, thus eliminating the need for daytime splinting when the splint may interfere with functional activities [Schultz-Johnson 2002].

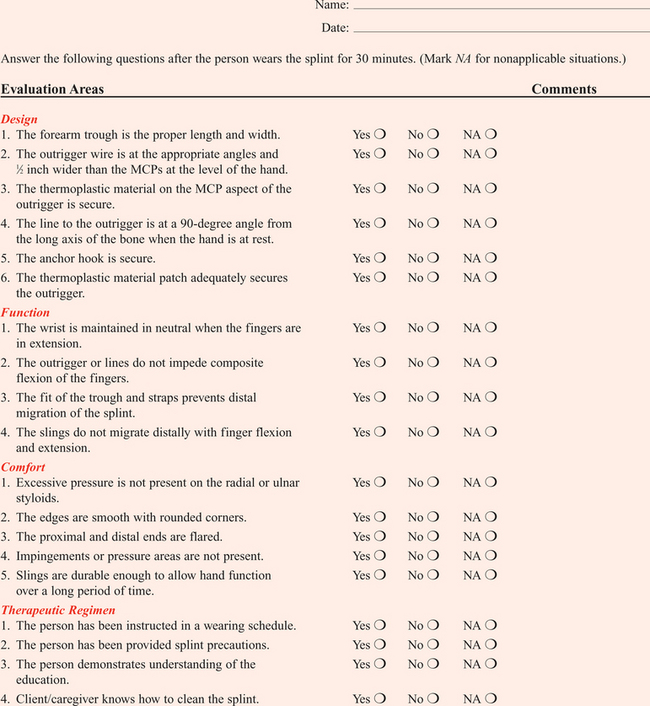

Fabrication of a Radial Palsy Splint

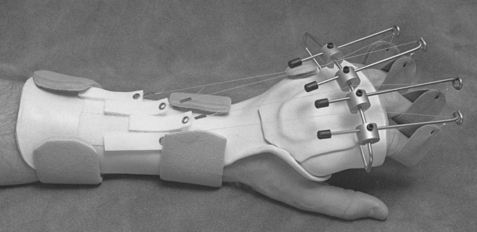

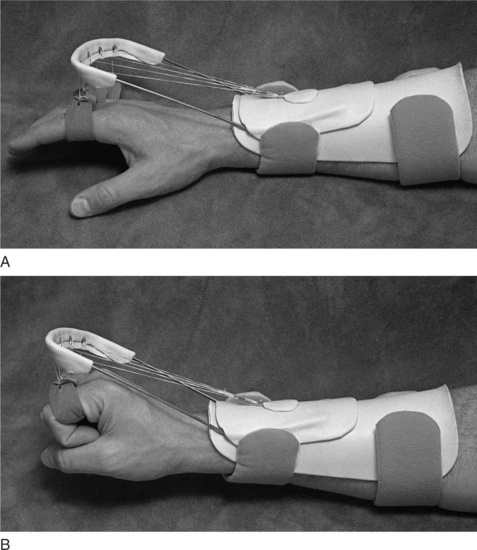

The radial nerve palsy splint does not involve the application of force to “mobilize” a joint, a process that typically defines dynamic splinting. Instead of a dynamic force, the splint uses a static line to support the fingers [Colditz 2002b]. The splint does, however, use an outrigger—which makes the construction similar to that of a dynamic splint. The splint described by the following instructions was initially designed by Crochetiere and was modified by Hollis and Colditz [Colditz 2002b].

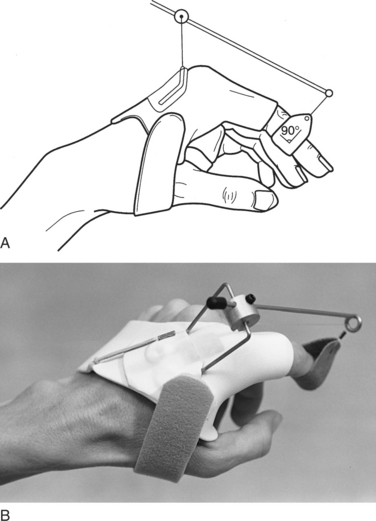

A lesion to the radial nerve above the elbow results in loss of active wrist, thumb, and finger MCP extension. The inability to actively extend and stabilize the wrist and fingers limits the functional use of the hand. For many people with a high radial nerve injury, a static wrist support that maintains wrist extension will greatly enhance the function of the hand. However, for tasks that require full finger extension (such as keyboarding, grasping large objects, and repetitive factory work) a splint that provides thumb and MCP support is necessary. The goal of this splint is to create a limited tenodesis action to allow functional grip [Colditz 1987]. The splint includes a dorsal base with a low-profile outrigger that spans from the wrist to the proximal phalanx of each finger.

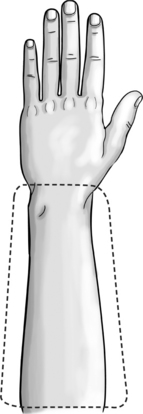

1. Draw a pattern that is the circumference and two-thirds the length of the forearm (Figure 11-28). Fabricate the dorsal forearm base of the radial nerve splint from a thermoplastic material that has self-adherence and drapability properties. Position the splint on the dorsal aspect of the forearm. Construct the splint so that it extends from the proximal aspect of the forearm to just proximal to the distal ulna. The base must be at least half the circumference of the forearm to prevent distal migration of the splint.

2. Apply straps to stabilize the splint base during formation of the outrigger.

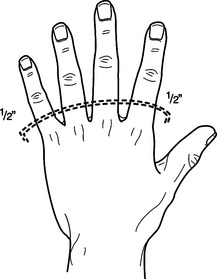

3. Make the outrigger from  -inch wire rod. The outrigger must be wider than the hand at the level of the MCPs by approximately ½ inch (Figure 11-29).

-inch wire rod. The outrigger must be wider than the hand at the level of the MCPs by approximately ½ inch (Figure 11-29).

4. To form the outrigger properly, draw an outline of the hand and mark the MCP and PIP joints. Draw a curved line halfway between the joints and extend it ½ inch beyond the hand on each side. Form the distal aspect of the outrigger along this curved line (Figure 11-29).

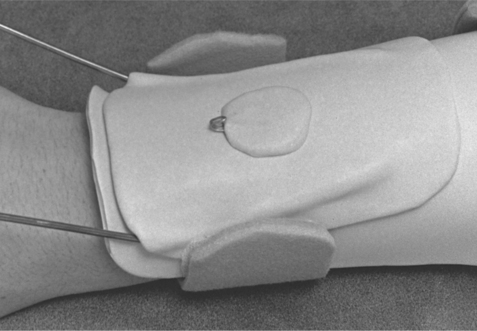

5. Conform the proximal end of the outrigger wire to the splint base. The wire will have a slight dorsal angle at the level of the wrist (Figure 11-29). Excessive outrigger wire may be snipped. After forming the outrigger, secure it to the base with a piece of thermoplastic material prepared with solvent.

6. Drape an additional piece of thermoplastic material over the distal aspect of the outrigger (over the phalanges). Punch holes directly above each finger.

7. To decrease wear on the cord, metal eyelet reinforcements may be placed in each hole.

8. Form a hook from a paper clip and place it in the middle of the dorsal forearm splint (Figure 11-30). Apply the hook to the base with a small piece of thermoplastic material prepared with solvent.

9. Place the splint on the person to secure the finger loops and cord. The length of the cord should allow full finger extension when the wrist drops to neutral (Figure 11-31). During active finger flexion, the wrist should extend slightly. If the finger loops impinge on the MCP or PIP joints, the loops can be trimmed on the volar surface.

Radial Palsy Splint Wearing Schedule

This splint should be worn throughout the day as tolerated to assist the person with functional activities. When not completing specific activities, and during the night, the radial nerve splint is replaced with a static wrist support splint for greater comfort.

Precautions for Dynamic Splinting

Therapists should consider specific precautions during application of dynamic splints. The first rule of dynamic splinting, and of all treatment, is to do no harm. Therapists should follow this rule by adhering to the following guidelines [Fess 2002].

• The person must be responsible enough to care for the splint and to follow a guided wearing schedule. A mobilization splint is not appropriate for a child or adult who cannot follow instructions.

• Keep in mind normal functional anatomy and biomechanics of the extremity.

• Apply minimal force. The amount of force should provide a low-grade stretch that is tolerable over a long period of time [Colditz 1990]. Signs indicating too much force include reddened pressure areas, cyanosis of the fingertips, and complaints of pain or numbness. A person will most likely not wear a splint that causes discomfort.

• Keep in mind the risks of wearing an ill-fitted splint (e.g., pressure points, skin breakdown, prolonged immobilization of noninvolved structures).

• Remember aesthetics. A person is more likely to wear a splint that has a finished, professional appearance. A low-profile splint may be more aesthetically pleasing.

• Monitor and adjust the splint frequently for accurate fit.

• Listen to the person. The splint must fit well, have a tolerable amount of tension, and cause minimal interference with daily activities. Complaints by the person require reevaluation of the splint’s fit.

• Use extreme caution when applying an external force to a hand that has decreased sensation. An increased risk of skin breakdown exists if a splint creates an excessive amount of force in the absence of sensory feedback.

• The altered joint mechanics of a person who has rheumatoid arthritis make static splinting more appropriate than dynamic splinting. A therapist may use dynamic splinting on a person who has rheumatoid arthritis, but only if specific indications are met. A dynamic splint may be used with rheumatoid arthritis with only very gentle tension applied as close to the joint as possible. The goal of splinting is to gently stretch involved soft tissue or to provide gentle resistance to strengthen weakened muscles [Cailliet 1994]. The therapist must be careful to avoid adverse reactions.

1. What are four possible goals of mobilizing splinting?

2. What are the complications associated with application of too much force?

3. What is the angle of pull between the long axis of the bone and the outrigger line the therapist must maintain?

4. What is the acceptable force per unit area for sling pressure?

5. What patient information should the therapist gather before considering a person for a mobilizing splint?

6. What is the difference between a high-profile and a low-profile outrigger? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each?

7. What are three methods for the application of force?

8. What criteria are used to determine whether to use static tension or elastic/dynamic tension?

9. What are the steps for attaching an outrigger wire to a splint base?

References

Austin, G, Slamett, M, Cameron, D, Austin, N. A comparison of high-profile and low-profile dynamic mobilization splint designs. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2004;17:335–343.

Brand, PW, Hollister, A. External stress: Effects at the surface. In Clinical Mechanics of the Hand. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993.

Brand, PW, Hollister, A. Terminology, how joints move, mechanical resistance, and external stress: Effect at the surface. In Clinical Mechanics of the Hand. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993.

Brand, PW, The forces of dynamic splinting. Ten questions before applying a dynamic splint to the hand. Rehabilitation of the Hand. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002.

Cailliet, R. Functional anatomy and joints: Injuries and disease. In Hand Pain and Impairment, Fourth Edition, Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1993:243–245.

Cannon, N, Foltz, R, Koepfer, J, Lauck, M, Simpson, D, Bromley, R. Mechanical principles. In: Manual of Hand Splinting. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1985:6–7.

Colditz, J. Low profile dynamic splinting of the injured hand. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1983;37:182–188.

Colditz, JC. Splinting for radial nerve palsy. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1987;1:18–23.

Colditz, JC. Dynamic splinting of the stiff hand. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Colditz, JC. Splinting the hand with a peripheral nerve injury. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Colditz, JC. Therapist’s management of the stiff hand. In Rehabilitation of the Hand. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995.

Duran, RJ, Coleman, CR, Nappi, JF, Klerekoper, LA. Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand. St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Fess, EE. Principles and methods of splinting for mobilization of joints. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Third Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Fess, EE. Splints: Mechanics versus convention. J Hand Therapy. 1995;8:124–130.

Fess, EE, McCollum, M. The influence of splinting on healing tissues. J Hand Therapy. 1998;11:125–130.

Fess, EE, Gettle, K, Philips, C, Janson, J. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Flowers, K, LaStayo, P. Effect of total end range time on improving passive range of motion. J Hand Ther. 1994;7:150–157.

Hardy, M. Principles of metacarpal and phalangeal fracture management: A review of rehabilitation concepts. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2004;34:781–799.

Hollister, A, Giurintano, D. How Joints Move: Clinical Mechanics of the Hand. St. Louis: Mosby, 1993.

Jebson, PL, Kasdan, ML. Hand Secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 1998.

Loth, TS, Wadsworth, CT. Orthopedic Review for Physical Therapists. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

May, E, Silfverskiold, K, Sollerman, C. Controlled mobilization after flexor tendon repair in zone Il: A prospective comparison of three methods. J Hand Surg. 1992;17A:942–952.

May, E, Silfverskiald, K, Sollerman, C. The correlation between controlled range of motion with dynamic traction and results after flexor tendon repair in zone II. J Hand Surg. 1992;17:1133–1139.

Prosser, R. Splinting in the management of proximal interphalangeal joint flexion contracture. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9:378–386.

Schultz-Johnson, K. Splinting the wrist: Mobilization and protection. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9:165–176.

Schultz-Johnson, K. Static progressive splinting. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002;15:163–178.

Smith, LK, Weiss, EL, Lehmkuhl, LD. Brunnstrom’s Clinical Kinesiology, Fifth Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1996.

Stewart, KM, van Strien, G. Postoperative management of flexor tendon injuries. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fifth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.