Elbow Immobilization Splints

1 Define anatomic and biomechanical considerations for splinting the elbow.

2 Discuss clinical/diagnostic indications for elbow immobilization splints.

3 Identify the components of elbow immobilization splints.

4 Describe the fabrication process for an anterior and posterior elbow splint.

5 Review precautions for elbow immobilization splinting.

6 Use clinical reasoning to evaluate a problematic elbow immobilization splint.

7 Use clinical reasoning to evaluate a fabricated elbow immobilization splint.

8 Apply knowledge about the application of elbow immobilization splints to a case study

Anatomic and Biomechanical Considerations

The elbow joint consists of three bones: distal humerus, proximal ulna (olecranon process), and the head of the radius. The elbow joint is comprised of three complex articulations: ulna-humeral, radio-capitellar, and proximal radio-ulnar. Flexion and extension of the elbow occur at the ulnohumeral joint. Flexion, extension, and rotation occur at the radiohumeral joint. Forearm rotation occurs at the proximal and distal radioulnar joints along a longitudinal axis [Morrey 2000a].

The elbow is particularly prone to contracture and stiffness due to the high congruity, multiple articulations, and the close relationship of ligaments and muscle to the joint capsule [Hotchkiss 1996]. For this reason prolonged immobilization is to be avoided whenever possible. The bony prominences, lateral and medial epicondyle, radial and ulnar heads, and olecranon require protection and special consideration during splinting.

Clinical Indications and Common Diagnoses

Splints are commonly constructed for elbow fractures, elbow arthroplasty, elbow instability, biceps and triceps repair, and cubital tunnel syndrome (Table 10-1).

Table 10-1

Conditions That Require an Elbow Immobilization Splint

| CONDITION | SUGGESTED WEARING SCHEDULE | TYPE OF SPLINT AND POSITION |

| Elbow fractures | After removal of the postoperative dressing, the therapist fabricates an elbow immobilization splint. The splint is worn at all times, and removed for exercises and hygiene if permitted. | Posterior angle depends on which structures need to be protected. |

| Elbow arthroplasty | After removal of the postoperative dressing the therapist fabricates an elbow immobilization splint or fits the client for a brace. The splint is worn at all times, and removed for protected range-of-motion exercises until the joint is stable. | Posterior in 90 degrees of flexion, or Bledsoe brace or Mayo elbow brace in 90 degrees. |

| Elbow instability | After removal of the postoperative dressing a posterior elbow immobilization splint in 120 degrees of flexion is provided. Therapist-supervised protected range-of-motion exercises are performed until the joint become more stable. The client is not permitted to remove the splint unsupervised. | Posterior in 120 degrees of flexion or brace locked in 120 degrees. |

| Biceps/triceps repair | Splint is worn at all times and removed for protected range-of-motion exercises. | Posterior elbow splint immobilized in prescribed angle based on structures requiring protection. Splint is usually adjusted to increase the angle of immobilization by 10 to 15 degrees per week at 3 weeks postoperatively. |

| Cubital tunnel syndrome | A nighttime splint is provided for use while sleeping. Proper positioning during work and leisure activities is reviewed. | Volar splint elbow immobilized in 30 to 45 degrees extension or reverse elbow pad. |

Splinting for Fractures

Elbow trauma can result in a simple one-bone fracture or a complex fracture/dislocation involving a combination of bones. These injuries vary by the bones and structures involved, and the extent of the injury. Elbow dislocations occur in isolation or along with a fracture. Both fractures and dislocations often include concomitant soft-tissue injury such as ligament, muscle, or nerve. Seven percent of all fractures are elbow fractures [Jupiter and Morrey 2000], and of this one-third involve the distal humerus. The mechanism of injury is a posterior force directed at the flexed elbow, often a fall to an outstretched hand, or axial loading of an extended elbow. Thirty-three percent of all elbow fractures occur in the radial head and neck by axial loading on a pronated forearm, with the elbow in more than 20 degrees of flexion [Morrey 2000c].

Radial head fractures are often associated with ligament injuries. Radial head fractures associated with interosseous membrane disruption and distal radial ulnar joint dislocation are termed Essex-Lopresti lesions. Twenty percent of elbow fractures occur in the olecranon as a result of direct impact or of a hyperextension force [Cabanela and Morrey 2000]. When the radial head dislocates anteriorly along with an ulnar fracture, the result is a Monteggia fracture. Another common fracture location along the proximal ulna is the coronoid process [Regan and Morrey 2000]. Elbow fractures are managed conservatively with closed manipulation or immobilization and surgically with open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) or external fixation.

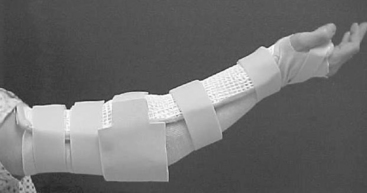

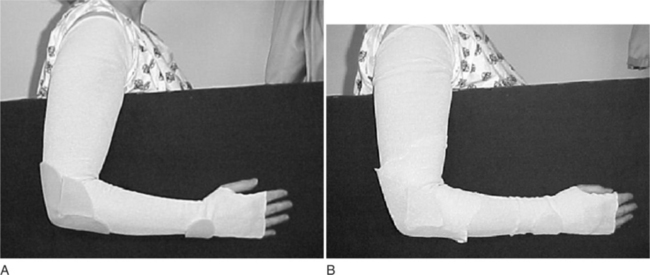

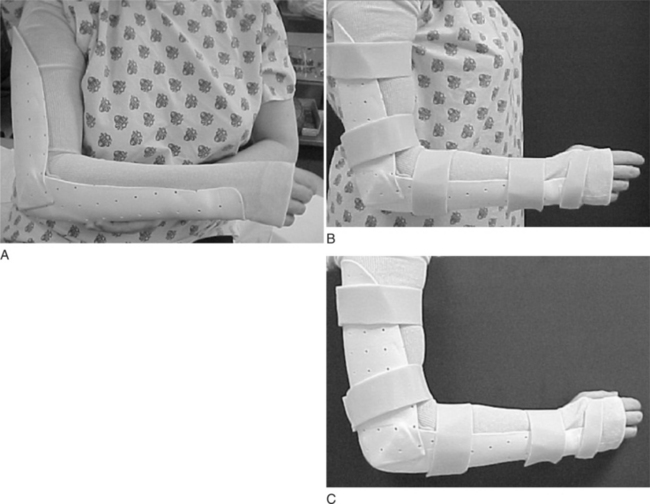

Healing structures are protected in a brace, cast, or custom-molded thermoplastic splint to maintain alignment and prevent deformity. Splint designs vary and are based on the surgeon’s preference, therapist’s experience, and the client’s needs. The protective splint is worn for as long as 2 to 8 weeks postoperatively, depending on the stability of the fracture/joint and the severity of the injury. The position and angle of immobilization are based on the type of fracture. Distal humeral fractures are immobilized in 90 degrees of elbow flexion, with the forearm in neutral rotation (Figure 10-1A).

Figure 10-1 (A) A posterior elbow immobilization splint in 90 degrees of flexion. (B) A posterior elbow immobilization splint in 75 degrees of flexion. (C) A posterior elbow immobilization splint in 120 degrees of flexion.

Olecranon and proximal ulna fractures often involve injury to the triceps tendon. To protect the injured tendon, the elbow is immobilized in 60 to 70 degrees of flexion, the forearm in neutral, and the wrist in slight extension (Figure 10-1B). Complex radial head fractures/dislocations and radial head replacements are immobilized in up to 120 degrees of flexion to stabilize the radial head (Figure 10-1C). The protective splint is worn continuously at first, and is removed only for protected exercises (when indicated) and for hygiene. Once the fracture/joint is considered stable, the splint is removed more frequently for exercises and light functional activities. The splint is gradually weaned during the day, and continues to be worn for sleep and protection until the fracture is completely stable [Barenholtz and Wolff 2001].

Splinting for Total Elbow Arthroplasty

Elbow arthroplasty refers to resurfacing or replacement of the joint. The primary goal of total elbow arthroplasty is pain relief with restoration of stability and functional motion (arc of 30 to 130 degrees). An elbow replacement is considered when the joint is painful, is restricted in motion, or has destroyed articular cartilage. Clients who are elderly or have low demands that present with rheumatoid arthritis, advanced post-traumatic arthritis, advanced degenerative arthritis, or nonunion and comminuted distal humeral fractures are good candidates for this surgery [Morrey 2000b]. Total elbow arthroplasty includes three types of implants: constrained, nonconstrained, and semiconstrained. The choice for a specific implant is based on the extent and cause of the disease, the specific needs of the client, and the surgeon’s preference [Cooney 2000, Morrey et al. Wolff 2000].

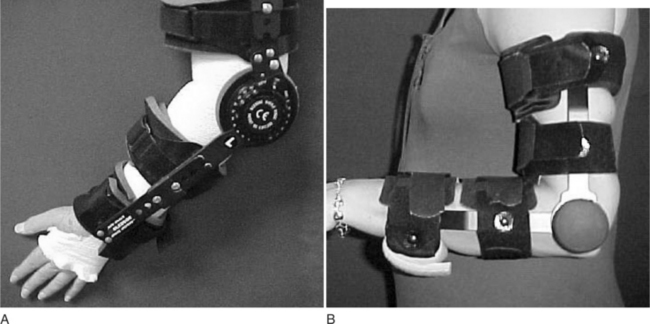

An immobilization splint or brace is provided on the first postoperative visit. Several options are available based on the preference of the surgeon and the experience of the therapist. Some surgeons prefer a brace such as the Bledsoe brace (Bledsoe Brace Systems, Grand Prairie) (Figure 10-2A) or Mayo Elbow Universal Brace (Aircast, Summit, NJ) (Figure 10-2B). The brace provides medial and lateral stability while allowing flexion and extension of the elbow. The parameters of the brace are preset to limit end range in both flexion and extension. Extension is set to tolerance, and flexion is determined by the condition of the triceps muscle and surgical repair. Protected range of motion exercises are initiated with the brace on for 2 to 3 weeks.

Figure 10-2 (A) A Bledsoe brace (Bledsoe Brace Systems, Grand Prairie, TX). (B) The Mayo elbow universal brace (Aircast, Summit, NJ).

Another common option is a posterior elbow immobilization splint (seeFigure 10-1A), a custom-molded thermoplastic splint positioned in 80 to 90 degrees of flexion. The advantages of this splint are that it fits well by conforming to the client’s elbow and that it can be remolded to accommodate changes in edema. Disadvantages of the splint include posterior pressure at the incision site and development of an elbow flexion contracture if the splint is not removed regularly for exercise. The splint is removed 3 to 4 times daily for the performance of protected range-of-motion exercises. In the presence of infection or instability, the splint is worn continuously and for a longer period of time. Many surgeons prefer no splint at all. Instead, the arm is wrapped lightly in an Ace bandage and positioned in a sling. This approach encourages early functional use and is comfortable and well tolerated. The rationale is that pain and postsurgical swelling will limit the end range of motion.

Splinting for Instability

Elbow instability results from a dislocation of the ulnohumeral joint and injury to the varus and valgus stabilizers of the elbow and the radial head [Hotchkiss 1996]. This injury often results from a forceful fall on an outstretched hand. The impact drives the head of the radius into the capitellum of the humerus [O’Driscoll 2000]. This may result in radial head and coronoid process fracture, medial collateral, and posterolateral and/or lateral collateral ligament disruption. When all of these structures are injured, the condition is described as the “terrible triad” [Hotchkiss 1996].

The treatment plan begins with fabrication of a custom thermoplastic posterior elbow shell with the elbow positioned in 120 degrees or more of flexion and the forearm in full pronation (seeFigure 10-1C). The wrist is included and splinted in neutral. A figure-of-eight strap may be added to further stabilize the elbow in 120 degrees for a larger-framed individual (Figure 10-3). The splint is worn at all times and removed 3 to 5 times daily for protected exercises. The elbow must be in 120 degrees or more of flexion to ensure approximation of the radial head.

If this is not achieved, an instability may occur. An alternative to the thermoplastic splint, and a preference of some surgeons is a Bledsoe brace (Bledsoe Brace Systems, Grand Prairie, TX) or the Mayo elbow universal brace (Aircast, Summit, NJ). The brace is locked in 120 degrees of elbow flexion and neutral foream rotation. The brace is worn at all times, and exercises are performed within protected range with the brace on. Some surgeons immobilize the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion if adequate stability was achieved intraoperatively.

Splinting for Biceps and Triceps Rupture

Distal biceps tendon rupture is uncommon and occurs more frequently in men than in women. The mechanism of injury is a strong extension force applied to the elbow in the flexed position, such as attempting to catch a heavy object with an outstretched hand [Kannus and Natri 1997]. Treatment varies from conservative management via immobilization to surgical repair via a one-incision or two-incision approach. The position and method of immobilization is determined by the preference of the surgeon. Common methods of immobilization include a brace or posterior elbow splint locked at 90 degrees of flexion and the forearm immobilized in pronation.

Some physicians prefer that the forearm be immobilized in neutral rotation, and yet others immobilize in supination. Elbow flexion is permitted as tolerated from the locked position of 90 degrees. Three weeks postoperatively elbow extension is increased by 10 to 15 degrees per week. The brace is generally worn for a period of 6 to 8 weeks. The benefit of using a brace for biceps tendon repairs is that it is easily adjusted to accommodate the change in the angle of motion. A thermoplastic splint requires frequent readjustment and remolding that can be cumbersome and time consuming.

Triceps rupture is commonly seen in olecranon fractures. Following a triceps repair, the elbow is immobilized in a splint 70 to 90 degrees. The client is instructed to actively extend the elbow to tolerance and to flex to the parameters of the splint or brace. Either a posterior or anterior splint is appropriate, although a posterior splint may be required to protect the incision.

Splinting for Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common site of nerve compression in the upper extremity following carpal tunnel [Blackmore 2002, Rayan 1992]. Anatomically, the ulnar nerve is susceptible to injury at the elbow. Injury to the nerve may occur as a result of trauma or prolonged or sustained motion that compresses the nerve over time [Fess et al. 2005]. Symptoms include pain and parasthesias (numbness, tingling) over the sensory distribution of the ulnar nerve, the ulnar two digits of the hand.

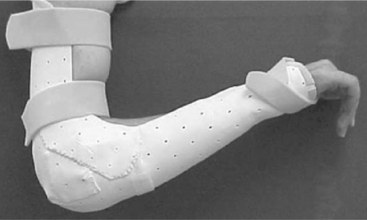

In advances stages, weakness and atrophy of the hypothenar muscles and thumb adductor may be seen. Conservative management focuses on avoiding postures and positions that aggravate the symptoms. Clients are instructed to avoid repetitive or sustained elbow flexion. For this purpose, a nighttime anterior elbow extension splint is fabricated with the elbow positioned in 30 to 45 degrees of extension (Figure 10-4). A commercial elbow pad is helpful to protect the ulnar nerve at the elbow. The pad can be reversed and worn anteriorly as an alternative to the splint to prevent elbow flexion.

Serial Static and Static Progressive Splinting of the Elbow

Serial static and static progressive splints are designed to increase motion in a stiff joint by providing a low-load and prolonged stretch [Flowers and LaStayo 1994]. Posttraumatic stiffness following elbow fractures and dislocations is the most common cause of elbow contracture. Other causes include osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis, congenital or developmental deformities, burns, and head injury. The elbow joint is prone to stiffness for several reasons. Anatomically, the joint is highly congruent. In most joints of the body, the tendinous portions of the muscles that act on the joint lie over the joint capsule. In the elbow, however, the brachialis muscle belly lies directly over the anterior joint capsule—making adhesion formation between the two structures inevitable following injury.

The elbow is often held in 70 to 90 degrees of flexion post-injury, as that is the position of greatest intracapsular volume for accommodation of edema. The thin joint capsule responds to trauma by thickening and becoming fibrotic, quickly adapting to this flexed position of the elbow. This results in a tethering of joint motion, particularly in the direction of extension [Wolff and Altman 2006]. Biomechanically, the strong (and often co-contracting) elbow flexors overpower the weaker elbow extensors—which challenges the ability to regain extension [Griffith 2002]. Last, the elbow joint is prone to heterotopic ossification following trauma and surgery.

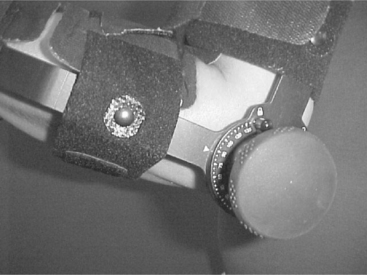

For extension contractures of less than 45 degrees, an anterior thermoplastic serial static elbow extension splint (Figure 10-5) is fabricated for use at night. This provides low-load prolonged positioning at the end range of elbow extension [Gelinas et al. 2000]. It is remolded into greater extension as tolerated. For extension contractures of greater than 45 degrees, a static progressive elbow splint is either fabricated or provided. An effective design for a static progressive elbow extension splint is the turnbuckle splint (Figure 10-6). It should be noted that this splint requires experience, expertise, and time. A simpler alternative is the Mayo elbow universal brace (Aircast, Summit, NJ), described previously. The brace can be locked in position and has a static progressive component that can be used to gain motion in both flexion and extension (Figure 10-7).

Figure 10-7 Static progressive component of Mayo elbow universal brace with dial shown up close. [Courtesy of Coleen Gately, DPT.]

For a custom static progressive elbow flexion splint, the D-ring design (referred to as a “come-along” splint) is often used effectively (Figure 10-8). It is often necessary to fabricate multiple static splints for limitations in elbow motion and forearm rotation, depending on the range-of-motion deficits of the client. Clients are instructed to wear the splint for 2-hour intervals, for a total of 6 hours daily. At first, only short intervals are tolerated. The goal is to develop a tolerance for longer intervals. Clients are instructed to adjust the tension, to allow increased motion as tolerated.

When more than one splint is required, the client may alternate the splints during the day or wear one during the day and the other at night for sleeping. The splint regimen is highly individualized and tailored to meet the specific needs and limitations of each client. Dynamic splinting is often not well tolerated, and is not recommended. Off-the-shelf prefabricated static progressive flexion/extension splints are currently available and are effective in many cases. The shape of the client’s arm, the degree of joint stiffness, and the firmness of joint end feel all impact the fit (and therefore effectiveness) of commercial splints.

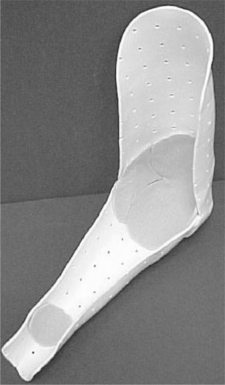

Features of the Elbow Immobilization Splint

The elbow splint immobilizes the elbow joint from moving in flexion and extension. A splint that extends distally to include the wrist will partially immobilize the forearm. For forearm immobilization splinting to prevent forearm rotation, a better choice would be a sugar tong or Muenster-type splint (Figure 10-9). The exact angle of immobilization is dictated by the structures requiring protection. A strong rigid material that conforms well is required to properly immobilize the elbow joint.

The wrist is most often included to prevent wrist drop and hand edema. The wrist is splinted in a neutral position of 15 degrees of extension. Unless otherwise indicated, the forearm is positioned in neutral rotation. The proximal portion of the splint should extend as high as possible while allowing clearance of the axilla. It is important to maximize the length of the lever arm in order to stabilize the joint in the splint. Reinforcement is required at the joint to add strength to the splint and prevent buckling of the material. The distal portion extends beyond the wrist to the distal palmar crease to allow thumb and digit motion while providing wrist support (Figure 10-10).

Indications for Anterior Elbow Splinting

Anterior elbow splinting is indicated in situations where there is a posterior wound that cannot tolerate posterior pressure or contact. It is also used to prevent or correct elbow flexion contractures. Following a contracture release of a stiff elbow, an anterior elbow splint would be used as a serial static splint to slowly gain extension of the elbow over time by remolding the splint in increased extension at weekly intervals. In addition, the anterior design is effective in blocking elbow flexion such as with ulnar nerve compression neuropathies.

Fabrication of an Elbow Immobilization Splint

The initial step in the fabrication of an elbow immobilization splint is the drawing of a pattern. Elbow splint patterns differ from hand patterns in that measurements of the client’s arm, elbow, and forearm are taken and recorded. A pattern is drawn based on the recorded measurements. The following materials will be required to fabricate the splint: a strong rigid perforated thermoplastic material such as Ezeform (Northcoast), ⅜-inch open cell contour padding,  -inch polycushion padding, 2-inch Velcro hook, 2-inch cushion strap, 2- or 3-inch stockinette, a tape measure, wax pencil, and scissors. It is important that a strong rigid material be used to support the elbow joint and weight of the arm, and to properly immobilize the joint.

-inch polycushion padding, 2-inch Velcro hook, 2-inch cushion strap, 2- or 3-inch stockinette, a tape measure, wax pencil, and scissors. It is important that a strong rigid material be used to support the elbow joint and weight of the arm, and to properly immobilize the joint.

The material must also be able to contour easily and should be of medium to low plasticity. Perforated material is chosen to provide ventilation and prevent moisture from accumulating in the splint. The following steps describe the fabrication process for a posterior elbow immobilization splint in 90 degrees of flexion. The angle of the splint is determined by the structures to be protected. For an anterior splint (seeFigure 10-4), the same procedures are followed (additional clearance is required at the axilla) and the splint is applied to the volar surface of the arm.

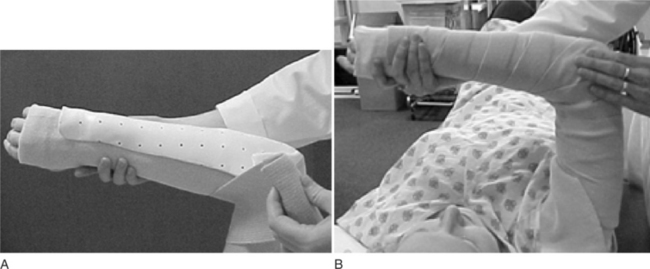

1. The client is positioned in the position of immobilization, and the joint is prepared for splinting. The position of the client is dependent on the diagnosis and the client’s tolerance. The easiest position for molding the splint is with the client supine, the shoulder in 90 degress of flexion, and the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion (Figure 10-11). Alternatively, the client may be seated with the shoulder slightly abducted.

Figure 10-11 Supine position for molding posterior immobilization splint. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

2. A stockinette is applied to the arm.

3. The bony prominences are padded prior to measuring and fabricating the splint (Figure 10-12A). This includes the olecranon, lateral epicondyle and radial head, medial epicondyle, and ulnar head and styloid at the wrist. Polycushion padding ( inch) is used to pad the prominences. The padding is then covered with an additional layer of stockinette to prevent the padding from adhering to the splint material (Figure 10-12B).

inch) is used to pad the prominences. The padding is then covered with an additional layer of stockinette to prevent the padding from adhering to the splint material (Figure 10-12B).

Figure 10-12 (A) Bony prominences are padded. (B) Padding is covered with additional layer of stockinette. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

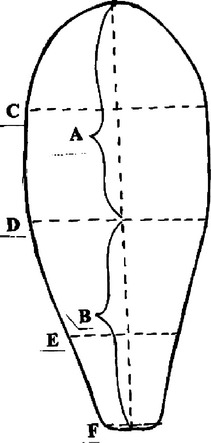

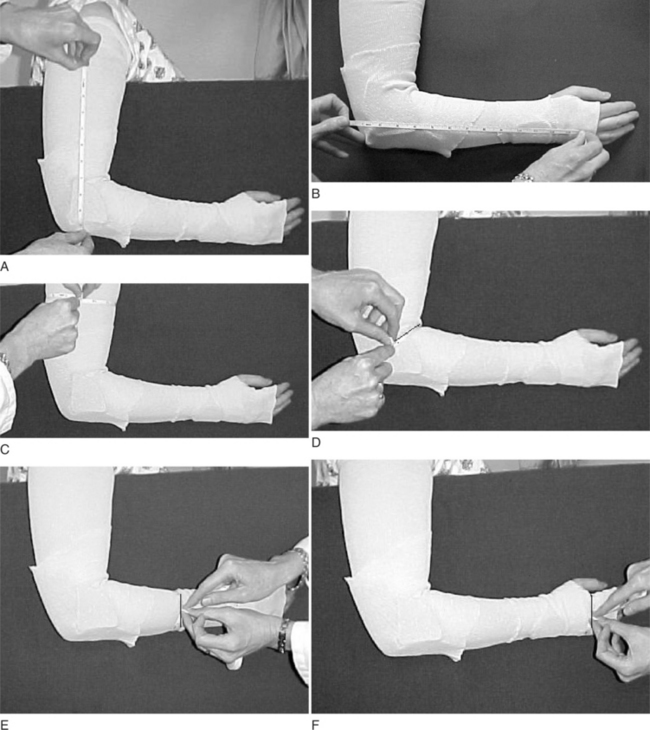

4. The following measurements are taken (Figure 10-13A through F):

Figure 10-13 (A) Length of axillary crease to olecranon process. (B) Length from olecranon process to the distal palmar crease. (C) Two-thirds the circumference of the upper arm. (D) Two-thirds the circumference of the elbow. (E) Two-thirds the circumference of the mid-forearm. (F) Two-thirds the circumference of the hand at the distal palmar crease level. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

a. The length from level of axillary crease to olecranon process. One inch is added to provide sufficient proximal support (Figure 10-13A).

b. The length from the olecranon process to the distal palmar crease on the ulnar aspect of the hand (Figure 10-13B).

c. Two-thirds the circumference of the upper arm (Figure 10-13C).

d. Two-thirds the circumference of the elbow (Figure 10-13D).

e. Two-thirds the circumference of the mid-forearm (Figure 10-13E).

f. Two-thirds the circumference of the hand at the distal palmar crease level (Figure 10-13F).

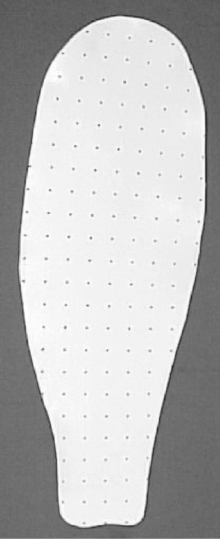

5. A pattern is drawn on paper towel (two pieces taped together will be needed) using the measurements taken (Figure 10-14).

6. The pattern is cut and measured on the client. The pattern should clear the axilla and extend laterally higher than the axilla to ensure proper support. The elbow portion must be wide enough to cover two-thirds of the circumference. A common error is to make the elbow portion too narrow. This compromises the stability of the splint, and does not provide adequate support. The distal portion extends to the distal palmar crease. The thenar eminence and distal palmar crease are cleared to allow full digit and thumb motion. Another common error is when the distal portion of the splint ends just distal to the wrist. The wrist is not sufficiently supported and is placed in an uncomfortable and often intolerable position. If errors are noted while the pattern is measured, adjustments are made or a new pattern is drawn.

7. Once it has been determined that the pattern is accurate, the pattern is traced with the wax pencil on the splint material and cut out (Figure 10-15).

8. The material is heated in a splint pan, removed, and patted dry.

9. The material is cut and reheated.

10. The material is dried and carefully draped over the arm in the proper position (Figure 10-16).

Figure 10-16 Material is draped over the arm in the proper position. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

11. The sides at the elbow are pinched and folded, carefully checking the elbow position. A common error is for the client to extend the elbow slightly during the molding process, causing a loss of the flexion angle (Figure 10-17).

Figure 10-17 (A) The sides at the elbow are pinched. (B) The sides at the elbow are folded carefully. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

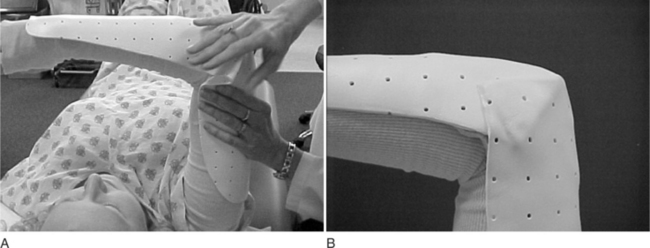

12. Light Ace wrap is used to position and mold the material, while continuing to support the arm in the correct position. Care should be taken to contour around the elbow and wrist joints (Figure 10-18A).

Figure 10-18 (A and B) A light Ace wrap is used to mold the material. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

13. Once the splint has cooled off, the Ace wrap is removed. The padding and outer stockinette layer is removed.

14. The elbow seams are smoothed and a space for pressure relief over the olecranon is created by gently pushing the material out (Figure 10-19).

Figure 10-19 (A and B) Elbow seams are smoothed and a space for pressure relief over the olecranon is created. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

15. The padding is inserted in the splint (Figure 10-20).

16. The fit is checked and adjustments are made as needed (Figure 10-21A).

Figure 10-21 (A) Fit is checked. (B) Velcro straps are applied. (C) Splint is applied and fit rechecked. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

17. Velcro straps are applied (Figure 10-21B) to the following:

18. The splint is applied and the fit rechecked (Figure 10-21C).

19. The client is educated in proper donning/doffing and wearing schedule.

Technical Tips for a Proper Fit

• Select a thermoplastic splinting material that is rigid enough to support the elbow yet conforms well to the arm and joint.

• Align the material along the arm. Make sure to properly position the material before you start molding.

• Use Ace wrap to position and hold the material in place. This will free up your hands to support the arm in the correct position and to contour around the elbow joint.

• Always determine that the client has full finger and thumb range of motion when wearing the splint by having him or her flex the digits and oppose the thumb.

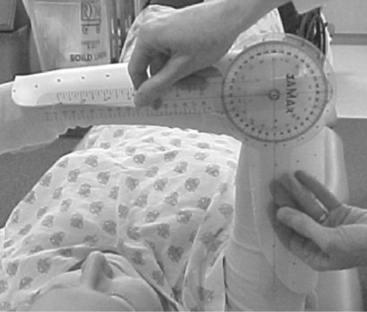

• Make sure the elbow, wrist, and forearm are at the correct angle. A frequent fabrication mistake when molding in the supine position is for the elbow to push into more extension during the molding process. To avoid this, continue to check the position of the elbow until the splint material is completely cool. Use a goniometer to check the position before the material cools (Figure 10-22).

Figure 10-22 A goniometer is used to check the angle at the elbow before the material cools. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

• Make sure the wrist is in neutral extension and deviation. It is common for the wrist to posture in flexion and ulnar deviation in the supine position. This mistake can occur because of a lack of careful monitoring of the person’s wrist position as the thermoplastic material is cooling. The therapist should closely monitor the wrist position in any splint that positions the wrist in neutral, because it is easy for the wrist to move in slight flexion. A quick spot check before the thermoplastic material is completely cool can address this problem.

• The forearm position should be carefully monitored so that the forearm does not posture in either pronation or supination.

• Make sure the splint extends as high as possible up the axilla, particularly on the lateral side. This will provide adequate support and leverage to properly immobilize the elbow.

• Make sure the medial side of the proximal portion clears the axilla to prevent irritation.

• Be careful not to wrap the Ace wrap tightly around the warm thermoplastic. This will leave marks and distort the material. It can also compress the proximal and forearm portion, making it too narrow. This will dig into the arm and forearm. To avoid this problem, lightly Ace wrap the material and while the material is still pliable pull the edges lightly away from the arm.

• If a mistake occurs, it is better to remold the entire splint rather than spot one area.

• Make sure there is enough material to support the elbow laterally and medially (two-third the circumference of the elbow). Often in larger individuals a thermoplastic strut must be added to provide adequate support (Figure 10-23).

Figure 10-23 A thermoplastic strut provides lateral support at the elbow. [Courtesy of Carol Page, PT, CHT.]

• In large-frame individuals a figure-of-eight strap may be required to properly secure the elbow in the splint.

• If you have access to assistance, an extra pair of hands is helpful in molding these large splints.

Precautions for Elbow Immobilization Splints

• Smooth all edges and line with moleskin or padding for clients with sensitive skin, particularly under the axilla and at the distal palmar crease and thumb web space.

• Edema in the elbow is common after injury or surgery to the joint. Make sure the client is scheduled for a follow-up visit within several days to modify and adjust the splint to accommodate for changes in edema.

• Open, draining, or infected wounds may require an alternative posterior elbow shell to protect and immobilize the joint while avoiding pressure over the wound (Figure 10-24).

1. What are three main indications for use of an elbow immobilization splint?

2. What are the precautions for splinting the elbow?

3. When might a therapist consider serial splinting with an elbow immobilization splint?

4. What are the purposes of immobilization splinting of the elbow?

5. What are the advantages of a custom splint over a commercial splint?

6. What are the advantages of a commercial splint over a custom splint?

References

Barenholtz, A, Wolff, A. Elbow fractures and rehabilitation. Orthopedic Physical Therapy Clinics of North America. 2001;10(4):525–539.

Blackmore, S. Therapist’s management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. In Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, et al, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition, St Louis: Mosby, 2000.

Cabanela, MF, Morrey, BF. Fractures of the olecranon. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:365–379.

Cooney, W. Elbow arthroplasty: Historical perspective and current concepts. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:583–601.

Fess, E, Gettle, K, Philips, C, Janson, J. Splinting for work, sports and the performing arts. In: Fess E, Gettle K, Philips C, Janson J, eds. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods. Third Edition. St Louis: Mosby; 2005:470–471.

Flowers, KR, LaStayo, P. Effect of total end range time on improving passive range of motion. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1994;7(3):150–157.

Gelinas, JJ, Faber, KJ, Patterson, SD, et al. The effectiveness for turnbuckle splinting for elbow contractures. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br). 2000;82(1):74–78.

Griffith, A. Therapist’s management of the stiff elbow. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, et al, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St Louis: Mosby; 2002:1245–1262.

Hotchkiss, R. Fractures and dislocations of the elbow. In Green DP, ed.: Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, Fourth Edition, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996.

Jupiter, JB, Morrey, BF. Fractures of the distal humerus in adults. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:293–330.

Kannus, P, Natri, A. Etiology and pathophysiology of tendon ruptures in sports. Scandinavian Journal of Science and Sports. 1997;7(2):107–112.

Morrey, BF. Anatomy of the elbow joint. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:13–42.

Morrey, BF. Complications of elbow replacement surgery. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:667–677.

Morrey, BF. Radial head fractures. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:341–364.

Morrey, BF, Adams, RA, Bryan, RS. Total replacement for post traumatic arthritis of the elbow. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1991;73(4):607–612.

O’Driscoll, S. Elbow dislocations. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:409–420.

Rayan, G. Ulnar nerve compression. Hand Clinics. 1992;8:325.

Regan, W, Morrey, BF. Coronoid process and monteggia fractures. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Third Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:396–408.

Wolff, A. Postoperative management after total elbow replacement. Techniques in Hand and Upper Extremity Surgery. 2000;4(3):213–220.

Wolff, A, Altman, E. Contracture release of the elbow. In: Mosca J, Cahill JB, et al, eds. Hopsital for Special Surgery: Cioppa-Postsurgical Rehabilitation Guidelines for the Orthopedic Clinician. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2006.