Splinting for the Fingers

1 Explain the functional and anatomic considerations for splinting the fingers.

2 Identify diagnostic indications for splinting the fingers.

4 Describe a boutonniere deformity.

5 Describe a swan-neck deformity.

6 Name three structures that provide support to the stability of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint.

7 Explain what buddy straps are.

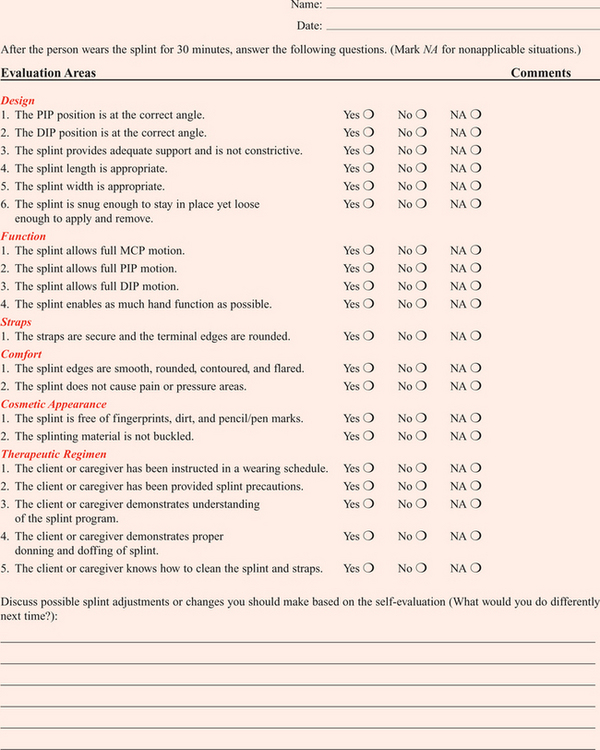

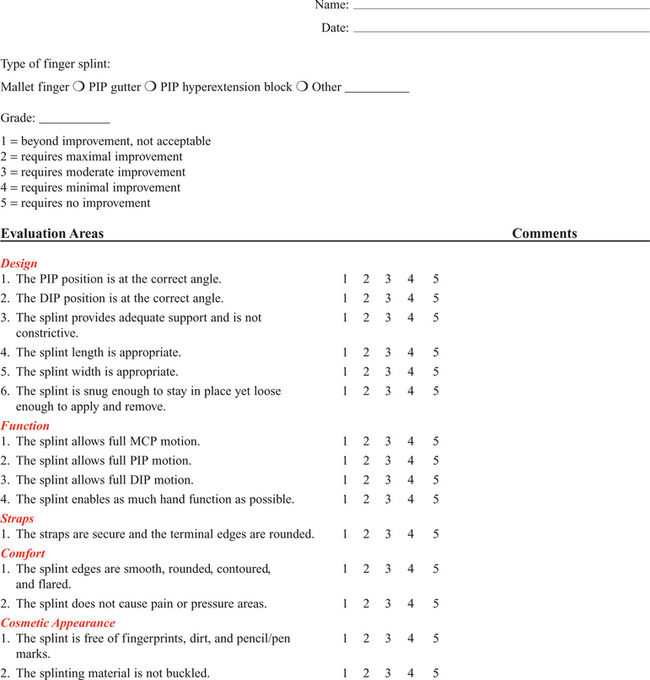

8 Apply clinical reasoning to evaluate finger splints in terms of materials used, strapping type and placement, and fit.

9 Discuss the process of making a mallet splint, a gutter splint, and a PIP hyperextension block splint.

Depending on the diagnosis, finger problems may require splints that cross the hand and wrist—or they may be treated with splints that are smaller. This chapter describes the smaller splints that are finger based, crossing the PIP and/or distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint—leaving the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint free.

Functional and Anatomic Considerations for Splinting the Fingers

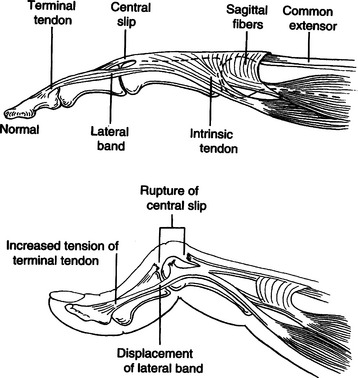

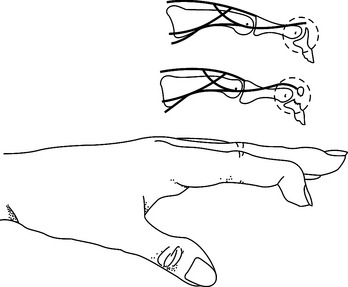

The PIP and DIP joints are hinge joints. These joints have collateral ligaments on each side that provide joint stability and restraint against deviation forces. The radial collateral ligament protects against ulnar deviation forces, and the ulnar collateral ligament protects against radial deviation forces. On the palmar (or volar) surface is the volar plate, which is a fibrocartilaginous structure that prevents hyperextension. The central extensor tendon crosses the PIP joint dorsally and is part of the PIP joint dorsal capsule. It is implicated in boutonniere deformities. The lateral bands, which are contributions from the intrinsic muscles, and the transverse retinacular ligament are additional structures that contribute to the delicate balance of the extensor mechanism at the PIP joint. They are implicated in boutonniere deformities and swan-neck deformities. The terminal extensor tendon attaches to the distal phalanx and is implicated in mallet finger injuries (Figure 12-1) [Campbell and Wilson 2002].

Figure 12-1 Structures that provide PIP joint stability include the accessory collateral ligament, the proper collateral ligament, the dorsal capsule with the central extensor tendon, and the volar plate. [From Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL. Hunter (2002). Mackin & Callahan’s Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby.]

For any finger problem, it is always important to prioritize edema control. Treatment for edema can often be incorporated into the splinting process. Examples of this would be the use of self-adherent compressive wrap under the splint or to secure the splint on the finger. For diagnoses that require splint use 24 hours per day but permit washing of the digit, it may be appropriate to fabricate one splint for shower use and another for use during the rest of the day. In general, thinner LTT is typically used on digits because it is less bulky yet strong enough to support or protect these relatively small body parts. On a stronger person or a person with larger hands, 3/32-inch material may be better to use than 1/16-inch thickness. Selecting perforated versus nonperforated splinting material is partly a matter of personal choice, but use caution with perforated materials because the edges may be rougher and there can be the possibility of increased skin problems or irregular pressure—particularly if there is edema. Smaller perforations seen in microperforated materials minimize the risk.

Because finger splints are so small, there is an increased possibility of them being pulled off in the covers during sleep or during activity. It is often necessary to tape them into place in addition to using Velcro straps. Be careful not to apply the tape circumferentially so as not to cause a tourniquet effect. An alternative solution is to use a long Velcro strap to anchor the splint around the hand or wrist.

Diagnostic Indications

Commonly seen diagnoses that require finger splints are mallet fingers, boutonniere deformities, swan-neck deformities, and finger sprains. These diagnoses are discussed separately in the sections that follow in terms of splinting indications, including consideration of wearing schedule and fabrication tips. Prefabricated splinting options are also addressed.

Mallet Finger

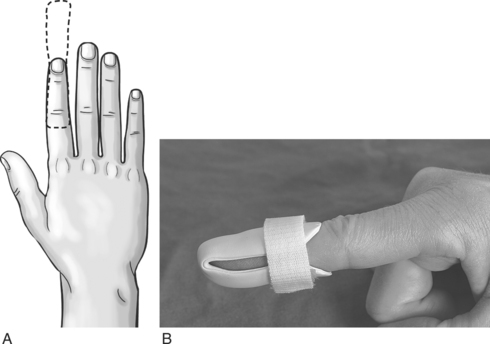

A mallet finger presents as a digit with a droop of the DIP joint (Figure 12-2). This posture often occurs as a result of axial loading with the DIP extended or flexion force to the fingertip. The terminal tendon is avulsed, causing a droop of the DIP. A laceration to the terminal tendon may also cause this problem [Hofmeister et al. 2003].

Figure 12-2 Mallet finger deformity. [From American Society for Surgery of the Hand (1983). The Hand: Examination and Diagnosis, Second Edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.]

With a mallet injury, the DIP joint can usually be passively extended to neutral—but the client is not able to actively extend it himself. This is called a DIP extensor lag. If the DIP joint cannot be passively extended, this is called a DIP flexion contracture. It is unlikely the DIP joint will develop a flexion contracture early on, but this can be seen in more long-standing cases.

Splinting for Mallet Finger

The goal of splinting for mallet finger is to prevent DIP flexion. Some physicians prefer the DIP joint to be splinted in slight hyperextension, whereas others prefer a neutral DIP position. It is good to clarify this with the doctor. If hyperextension is desired, care must be taken not to excessively hyperextend because this may compromise blood flow to the area. Either way, it is very important that the splint does not impede PIP flexion unless there are specific associated issues such as a secondary swan-neck deformity that would justify limiting the PIP joint’s mobility.

The DIP joint should be splinted for about 6 weeks to allow the terminal tendon to heal. This terminal tendon is a very delicate structure, and for this reason the joint should not be left unsupported or be allowed to flex for even a moment during this 6-week interval. It can be challenging to achieve this continuous DIP support because there is also the need for skin care and air flow. Practice with the client so that there is good understanding of techniques to support the DIP joint while performing skin hygiene and when applying and removing the splint [Cooper 2007].

After about 6 weeks of continual splinting and with medical clearance, the client is weaned off the splint. It is usually still worn at night for several weeks. At this time, it is very important to watch for the development of a DIP extensor lag. If this is noticed, resume use of the splint and consult the physician.

Boutonniere Deformity

A boutonniere deformity is a finger that postures with PIP flexion and DIP hyperextension (Figure 12-3). This deformity can result from axial loading, tendon laceration, burns, or arthritis. The central extensor tendon (also called the central slip) is disrupted, which leads to the imbalance of the extensor mechanism as the lateral bands displace volarly. If not treated in a timely manner, the PIP joint extensor lag may become a flexion contracture. In addition, the DIP joint may lose flexion motion due to tightness of the oblique retinacular ligament (ORL), also called the ligament of Landsmeer.

Splinting for Boutonniere Deformity

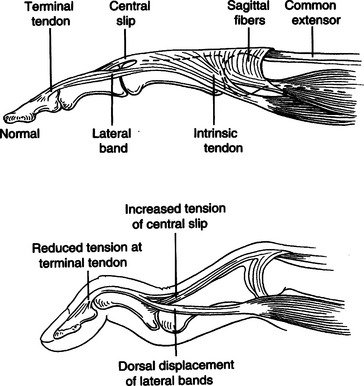

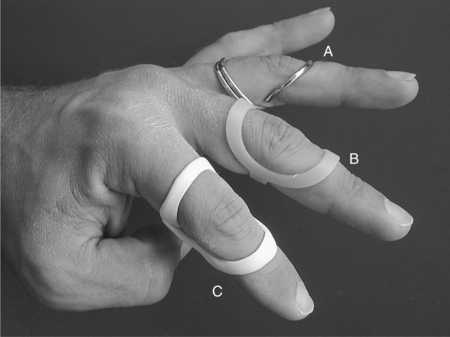

The goal of splinting for boutonniere deformity is to maintain PIP joint extension while keeping the MCP and DIP joints free for about 6 to 8 weeks. If there is a PIP flexion contracture, a prefabricated dynamic three-point extension splint might be used—or a static splint can be adjusted serially with the goal of achieving full passive PIP extension. There are various types of splints for boutonniere deformity, including simple volar gutter splints.Figure 12-4 depicts some common options for splinting the PIP joint in extension while keeping the DIP joint free. In some cases, including the DIP joint in the splint may be preferable because this will increase the mechanical advantage. It is usually acceptable to do this if the ORL is not tight.

Figure 12-4 Extension splints. (A) Tube. (B) Capener. (C) Custom. [From Burke SL, Higgins J, McClinton MA, Saunders R, Valdata L (2006). Hand and Upper Extremity Rehabilitation: A Practical Guide, Third Edition. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone.]

Serial casting is also an option with this diagnosis (Figure 12-5). This technique requires training and practice before being used on clients [Bell-Krotoski 2002, 2005]. After 6 to 8 weeks of splinting and with medical clearance, the client is weaned off the splint. At this time, it is important to watch for loss of PIP extension. If this is noted, adjust splint usage accordingly.

Swan-neck Deformity

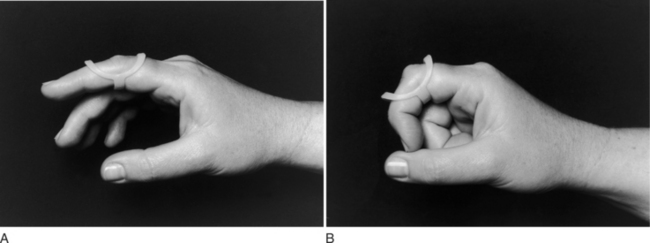

A swan-neck deformity is seen when the finger postures with PIP hyperextension and DIP flexion (Figure 12-6). Positionally, the swan-neck deformity at the PIP and DIP is the opposite of the boutonniere deformity. It may be possible to correct the PIP and DIP joints passively—or they may be fixed in their deformity positions. There are multiple possible causes of this deformity that may occur at the level of the MCP, the PIP, or the DIP joints. As with boutonniere deformity, the result is an imbalance of the extensor mechanism—but with a swan-neck deformity the lateral bands displace dorsally. In addition to other traumatic causes, it is not uncommon for people with rheumatoid arthritis to demonstrate swan-neck deformities [Alter et al. 2002, Deshaies 2006].

Splinting for Swan-neck Deformity

The goal of splinting for swan-neck deformity is to prevent PIP hyperextension and to promote DIP extension while not restricting PIP flexion. A dorsal gutter with the PIP joint in slight flexion (about 20 degrees) can be made. If the DIP demonstrates an extensor lag, the splint can cross the DIP and a strap can be added to support the DIP in neutral. Less restrictive styles of splints are shown inFigure 12-7. These are three-point splints that prevent PIP hyperextension but allow PIP flexion. They can be either custom formed or prefabricated.

Figure 12-7 PIP hyperextension block (swan-neck) splints. (A) Custom-ordered silver ring splint. (B) Prefabricated polypropylene Oval 8 splint. (C) Custom low-temperature thermoplastic splint. [From Burke SL, Higgins J, McClinton MA, Saunders R, Valdata L (2006). Hand and Upper Extremity Rehabilitation: A Practical Guide, Third Edition. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone.]

Finger PIP Sprains

Finger sprains may be ignored by clients as trivial injuries, but they can be very painful and functionally debilitating—with the potential for chronic swelling and stiffness and surprisingly long recovery time. Uninjured digits are at risk of losing motion and function, which further complicates the picture. Prompt treatment can favorably affect the client’s outcome and expedite return to occupations impacted by the injury.

PIP sprains are graded in terms of severity, from grade I to grade III.Box 12-1 describes these grades and identifies proper treatment. PIP joint dislocations are also described in terms of the direction of joint dislocation (i.e., dorsal, lateral, or volar). PIP joint sprains are associated with fusiform swelling, which is fullness at the PIP joint and proximal and distal tapering. Edema control is critical with this diagnosis.

Splinting for Finger PIP Sprains

The goal of splinting finger PIP sprains is to support the PIP joint and promote healing and stability. Splinting options for the injured PIP joint with extension limitations are similar to those used for boutonniere deformities. If there is a PIP flexion contracture, dynamic or serial static PIP extension splinting is used—or serial casting may be considered. If there has been a volar plate injury, a dorsal gutter is fabricated to block about 20 to 30 degrees of PIP extension while allowing PIP flexion (Figure 12-8).

Figure 12-8 Dorsal gutter splint blocking about 20 to 30 degrees of PIP extension. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson RJ (2005). Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby.]

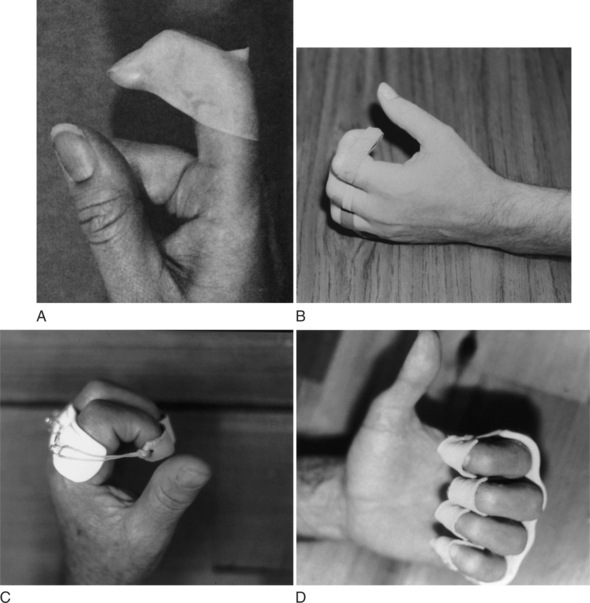

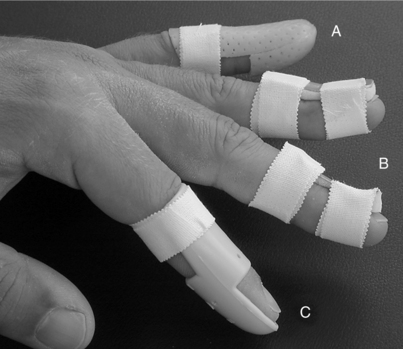

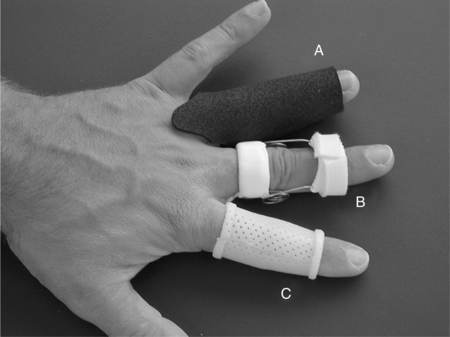

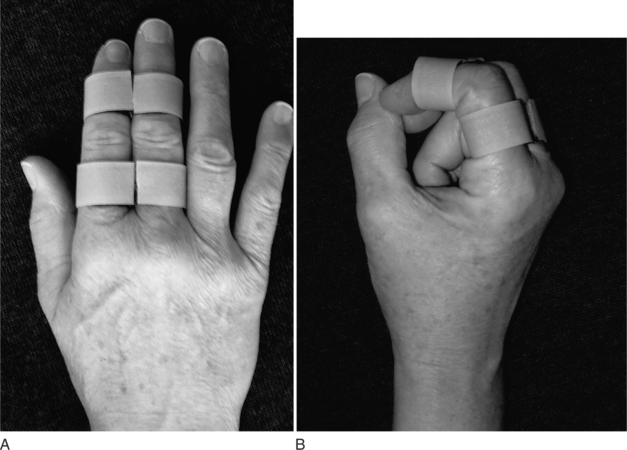

Buddy straps (Figure 12-9) are used to promote motion and support the injured digit. There are many different styles to choose from [Campbell and Wilson 2002]. An offset buddy strap may be needed, especially for small finger injuries due to the length discrepancy between the small and ring fingers.

Figure 12-9 Examples of buddy straps for proximal interphalangeal collateral ligament injuries. [From Burke SL, Higgins J, McClinton MA, Saunders R, Valdata L (2006). Hand and Upper Extremity Rehabilitation: A Practical Guide, Third Edition. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone.]

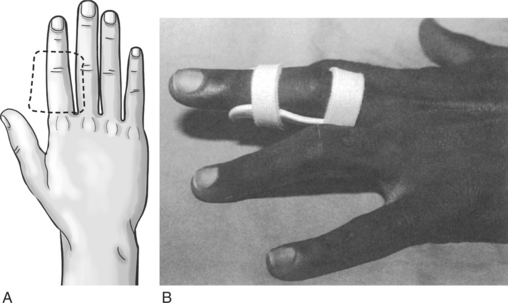

The physician will indicate what arc of motion is safe, according to the injury and joint stability. It is important not to apply lateral stress to the injured tissues. For example, if the index finger has an injury to the radial collateral ligament do not put ulnar stress on it. Lateral pinch would also be problematic in this instance. Sometimes it is necessary to custom fabricate a PIP gutter that corrects lateral position as well.Figure 12-10 shows a digital splint that provides lateral support.

Figure 12-10 PIP extension splint with lateral support. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson RJ (2005). Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby.]

Generally, PIP finger sprains are at risk for stiffness and are prone to developing flexion contractures. For this reason, a night PIP extension splint is often appropriate to use. However, this type of injury may also present problems achieving PIP/DIP flexion as well. In this instance, splinting can be provided along with exercises to gain flexion passive range of motion. Examples of flexion splints are shown inFigure 12-11. Such choices must be applied very gently, and tissue tolerances should be monitored carefully.

Precautions for Finger Splints

• Monitor skin for signs of maceration and/or pressure both on the splinted finger and adjacent fingers that come into contact with the splint.

• Check splint edges and straps for signs of tightness.

• Provide written instructions, and practice with clients so that they are correctly following guidelines for splint care and use.

Occupation-Based Splinting

Some finger splints may help with hand function by decreasing pain and providing stability. However, many finger splints can certainly interfere with daily hand use. Understandably, clients may be tempted to remove their splints in order to participate in activities they enjoy. To help prevent this from happening, therapists should incorporate an occupation-based approach.

Examples of Occupation-Based Finger Splinting

An elderly retired male enjoyed woodworking but was unable to use his woodworking tools comfortably due to arthritis-related pain and instability of the index finger PIP joint. He expressed interest in a PIP joint protective gutter splint to help him use his tools. To determine the best position of the PIP joint splint, he brought his tools to therapy and demonstrated the finger position he needed. A splint was made that provided support during this task.

A client with a mallet injury came to a clinic with maceration under the splint. He stated that he was wearing his splint in the shower and keeping the wet splint on his finger all day. In addition to reviewing skin care guidelines and practicing safe protected donning and doffing of the splint, an additional splint was made to use while showering. This allowed him to apply a dry splint after his shower. With this solution, he was able to avoid further skin maceration.

Fabrication of a Dorsal-Volar Mallet Splint

This splint is indicated for a mallet injury.Figure 12-12A represents a detailed pattern that can be used for any finger.Figure 12-12B shows a completed splint. This splint has some adjustability for fluctuations in edema, which can be advantageous (3/32-inch nonperforated material works well for this splint). An alternative splint design is a DIP gutter splint.Figure 12-13 represents a detailed pattern for this alternative.

1. Mark the length of the finger from the PIP joint to the tip.

2. Mark the width of the finger.

3. Cut out the pattern and round the four edges.

4. Trace the pattern on a sheet of thermoplastic material.

5. Warm the material slightly to make it easier to cut the pattern out of the thermoplastic material.

6. Heat the thermoplastic material.

7. Apply the material to the client’s finger, clearing the volar PIP crease. Be gentle with the amount of hand pressure over the dorsal DIP because this is usually quite tender.

8. Maintain the DIP in extension or slight hyperextension, depending on the physician’s order.

9. Allow the material to cool completely before removing the splint.

10. Ensure proper fit of the splint. It should stay in place securely with a thin ½-inch Velcro strap.

Technical Tips for Proper Fit of Mallet Splints

• Finger splints may seem easy to make because they are small. However, it may actually take extra time to fabricate them precisely. Do not be surprised if you wind up needing extra time to make and fine-tune these small splints.

• Ordinary Velcro loop straps may feel bulky on small finger splints. Thinner strap material that is ½ inch in width and less bulky can be very effective with finger splints.

Prefabricated Mallet Splints

Figure 12-14 shows various styles of mallet splints. If there has been surgery and the client has a percutaneous pin, the splint must accommodate this. The DIP splint can be a volar gutter splint, a volar-dorsal splint, or a stack splint. A prefabricated Alumifoam splint is sometimes used, but there may be inconveniences as well as skin issues associated with the adhesive tape used to secure it. Prefabricated or custom fabricated stack splints need to be monitored for clearance at the dorsal distal edge because this is an area prone to tenderness and edema related to the injury itself.

Mallet Finger Impact on Occupation

Mallet injuries can result in awkward hand use and can also limit the freedom of flexion of uninvolved digits. It is very important to teach clients to maintain active PIP motion of the involved digit and to use compensatory skills such as relying on uninjured fingertips for sensory input.

Fabrication of a PIP Gutter Splint

This splint is indicated for a PIP sprain injury.Figure 12-15A represents a detailed pattern that can be used for any finger.Figure 12-15B shows a completed splint (3/32-inch nonperforated material works well for this splint).

Figure 12-15 (A) PIP gutter splint pattern. (B) Completed PIP gutter splint. [From Clark GL, Shaw Wilgis EF, Aiello B, Eckhaus D, Eddington LV (1998). Hand Rehabilitation: A Practical Guide, Second Edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone.]

1. Mark the length of the finger from the web space to the DIP joint.

2. Mark the width of the finger, adding approximately ¼ to ½ inch on each side—depending on the size of the digit.

3. Cut out the pattern and round the four edges.

4. Trace the pattern on a sheet of thermoplastic material.

5. Warm the material slightly to make it easier to cut the pattern out of the thermoplastic material.

6. Heat the thermoplastic material.

7. Position the client’s hand with the palm up so that the material can drape nicely.

8. Apply the material to the client’s finger, clearing the MP and DIP creases and positioning the PIP joint in the desired position (this is typically the available passive extension). Be gentle with the amount of hand pressure used over the PIP joint and over the sides of the joint.

9. Roll the edges of the splint as needed for comfort and clearance of MP and DIP joint motions.

10. Allow the material to cool completely before removing the splint.

Technical Tips for Proper Fit of PIP Gutter Splints

• Straps should not be too tight because this can cause edema. However, they must fit closely enough to provide a secure fit.

• Modify the height of finger splint edges so that straps can have contact with the skin. If the edges are too high, the straps will not be effective.

• If you are trying to achieve full PIP extension, consider placing a strap directly over the PIP joint. However, be careful to closely monitor skin tolerance.

Prefabricated PIP Splints

Figure 12-16 shows examples of prefabricated PIP extension splints. Remember that prefabricated splints do not always fit well or accommodate edema. In addition, there can be problems associated with distribution of pressure and skin tolerance and with excessive joint forces.

Impact of PIP Injuries on Occupations

PIP joint injuries can limit the flexibility and function of the entire hand. Reaching into the pocket or grasping a tool may be impeded. Pain can interfere with comfort doing a simple but socially significant thing such as a handshake. Rings may no longer fit over the injured joint. Early appropriate therapy can help restore these functions to our clients.

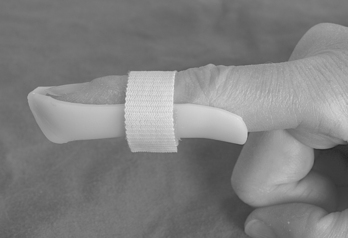

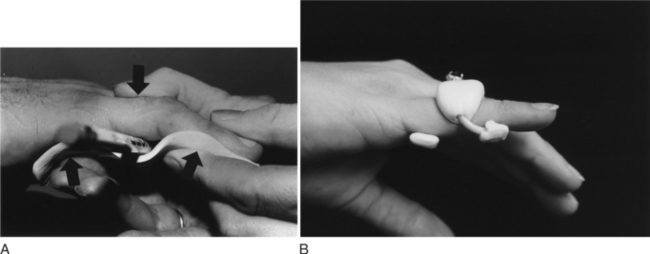

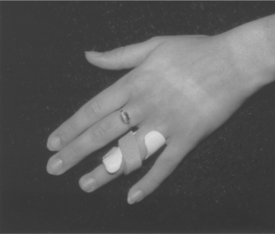

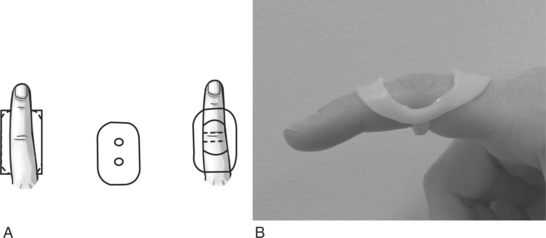

Fabrication of a PIP Hyperextension Block (Swan-Neck Splint)

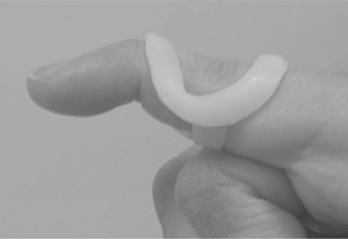

This splint is indicated for a finger with a flexible swan-neck deformity.Figure 12-17A represents a detailed pattern that can be used for any finger.Figure 12-17B shows a completed splint. An alternative splint design involves wrapping a thin strip or tube of thermoplastic material in a spiral fashion (Figure 12-18). A properly fitting splint will effectively block the PIP in slight flexion when the finger is actively extended and allow unrestricted active PIP flexion. A thin (1/16 inch) nonperforated thermoplastic material (such as Orfit or Aquaplast) works well for this splint. It is especially important to minimize bulk if multiple fingers need to be splinted on the same hand—so that splints do not get caught on each other.

Figure 12-17 (A) PIP hyperextension block splint pattern. (B) Completed PIP hyperextension block splint.

1. Mark the length of the finger from the web space to the DIP joint.

2. Mark the width of the finger, adding approximately ¼ inch on each side.

3. Cut out the pattern and round the four edges.

4. Trace the pattern on a sheet of thermoplastic material.

5. Cut the pattern out of the thermoplastic material. Cutting thin material does not require heating of the plastic first.

6. Mark location for holes, leaving an approximately ¼- to ½-inch bar of material in the center of the splint.

8. Apply a light amount of lotion to the finger to enable material to slide over the finger easily.

9. Heat the thermoplastic material.

10. Slightly stretch the holes so that they are just large enough to slide the finger through. Be careful not to overstretch because the splint will be too loose.

11. Slide the material over the finger, weaving the finger up through the proximal hole and down through the distal hole.

12. Center the volar thermoplastic bar directly under the PIP joint, and the dorsal distal and proximal ends of the splint over the middle and proximal phalanges.

13. Keep the PIP in slight flexion (approximately 20 to 25 degrees) as you form the splint on the finger.

14. Roll the edges of the volar thermoplastic bar as needed to allow unrestricted PIP flexion.

15. Fold the lateral sides of the splint volarly and contour the material to the finger.

16. Allow the material to cool completely before removing the splint.

17. Ensure proper fit of the splint. The splint should be loose enough to slide over the PIP joint yet snug enough to not migrate or twist on the finger. It should allow full PIP flexion and effectively prevent the PIP from going into hyperextension.

Technical Tips for Proper Fit of Hyperextension Block (Swan-neck Splint)

• A common mistake is to allow the PIP joint to go into extension while fabricating the splint. Closely monitor PIP position to make sure it remains in slight flexion during the splinting process.

• If the PIP joint is enlarged or swollen, it may be very difficult to slide the splint off the finger once the splint is made. This can be avoided by gently sliding the splint back and forth over the PIP joint a few times before the thermoplastic material is fully cooled.

• Because this splint is meant to enable function, make sure to minimize splint bulk by flattening the volar PIP bar and lateral edges as much as possible so they do not impede the grasping of objects.

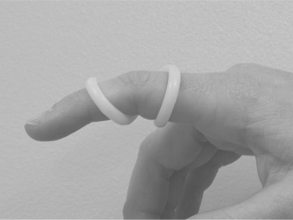

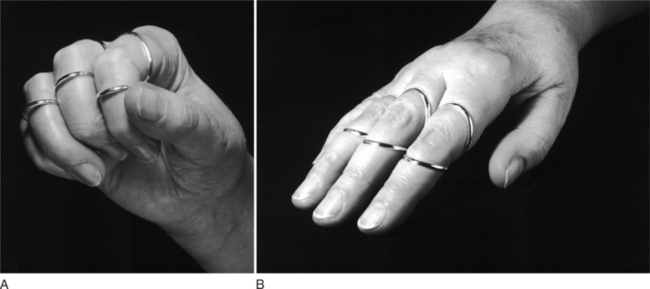

Prefabricated Hyperextension Block Splints

Swan-neck splints are commercially available, and offer some advantages over custom-fabricated thermoplastic splints. They are more durable, less bulky, and often more cosmetically pleasing to clients. Therapists use ring sizers to determine the splint size needed for each finger. Custom-ordered ring splints made of silver or gold (Figure 12-19) are attractive, unobtrusive, and flexible enough to be adjusted for fluctuations in joint swelling. However, they are more costly. Prefabricated splints made of polypropylene (Figure 12-20) are a less expensive alternative that offer durability and a streamlined fit. Their fit can be slightly modified by a therapist using a heat gun, but they cannot be adjusted by clients in response to variations in joint swelling.

Impact of Swan-neck Deformities on Occupations

Swan-neck deformities often cause difficulty with hand closure. PIP tendons and ligaments can catch during motion, and the long finger flexors have less mechanical advantage to initiate flexion when the PIP starts from a hyperextended position. A PIP hyperextension block should improve the client’s hand function by allowing the PIP to flex more quickly and easily, enabling the ability to grasp objects.

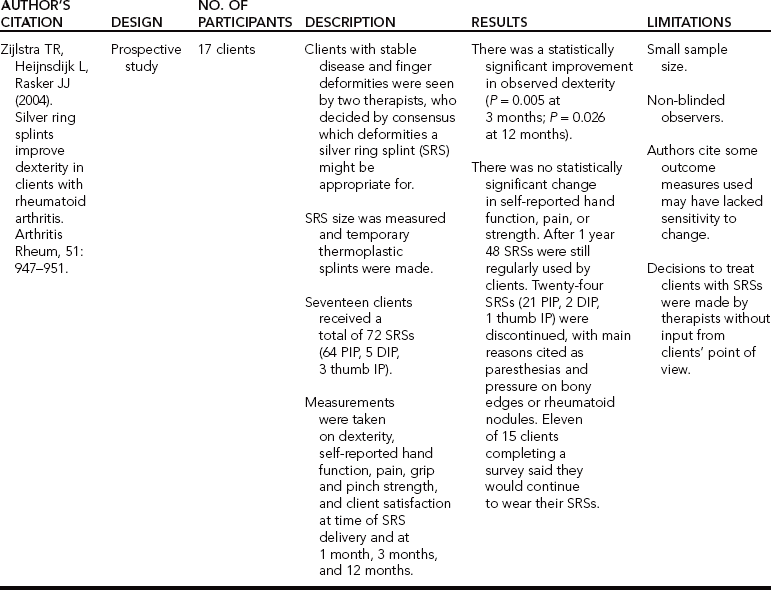

Conclusions, Evidence-Based Practice Information Chart

Table 12-1 presents one study published on PIP hyperextension block splints. Considering how frequently finger splints are used, there is a surprising lack of evidence to support their efficacy. This explains why only one study was located.

Despite the lack of evidence for their use, finger splints are a mainstay of care for many common finger problems. Finger biomechanics are very complicated. Added to this, there are multiple custom and prefabricated splints to select from. These challenges can understandably obfuscate decision making, particularly for newer therapists. We hope this chapter helps you use sound clinical reasoning to work collaboratively with clients. This will ensure that the best splint is selected based on each client’s clinical needs and occupational demands.

2. What is the posture of a finger with a boutonniere deformity?

3. What is the posture of a finger with a swan-neck deformity?

5. What structures provide joint stability and restraint against PIP deviation forces?

6. What is the difference between an extensor lag and a flexion contracture?

7. What type of finger splint is typically used for a swan-neck deformity?

8. What position is the DIP splinted in when treating a mallet finger?

9. What position is the PIP splinted in when treating a boutonniere deformity?

10. What position is the PIP splinted in when treating a swan-neck deformity?

References

Alter, S, Feldon, P, Terrono, AL. Pathomechanics of deformities in the arthritic hand and wrist. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1545–1554.

Bell-Krotoski, J. Plaster cylinder casting for contractures of the interphalangeal joints. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1839–1845.

Bell-Krotoski, J. Plaster serial casting for the remodeling of soft tissue, mobilization of joints, and increased tendon excursion. In: Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR, eds. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods. Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2005:599–606.

Campbell, PJ, Wilson, RL. Management of joint injuries and intraarticular fractures. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:396–411.

Cooper, C. Common finger sprains and deformities. In: Cooper C, ed. Fundamentals of Hand Therapy: Clinical Reasoning and Treatment Guidelines for Common Diagnoses of the Upper Extremity. St. Louis: Mosby; 2007:301–319.

Deshaies, L. Arthritis. Pendleton HM, Schultz-Krohn W, eds. Pedretti’s Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction. Sixth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2006:950–982.

Hofmeister, EP, Mazurek, MT, Shin, AY, Bishop, AT. Extension block pinning for large mallet fractures. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2003;28A:453–459.