Antispasticity Splinting

1 Identify and describe the two historic trends in upper extremity tone-reduction splinting (orthotics). (Note: The authors use the terms splint and orthosis interchangeably in this chapter.)

2 Compare the strengths and weaknesses of dorsal and volar forearm platforms (troughs). (Note: The authors use the terms platform and trough interchangeably in this chapter.)

3 Discuss the neurophysiologic rationale supporting the use of the finger spreader and hard cone.

4 Discriminate between the passive and dynamic components of spasticity.

5 Describe the difference between submaximum and maximum ranges as they relate to tone-reduction splints.

6 Identify and describe the two major components of orthokinetic splints.

7 Describe one unique characteristic for each of the following materials: plaster bandage, fiberglass bandage, inflatable splints, cylindrical foam, neoprene.

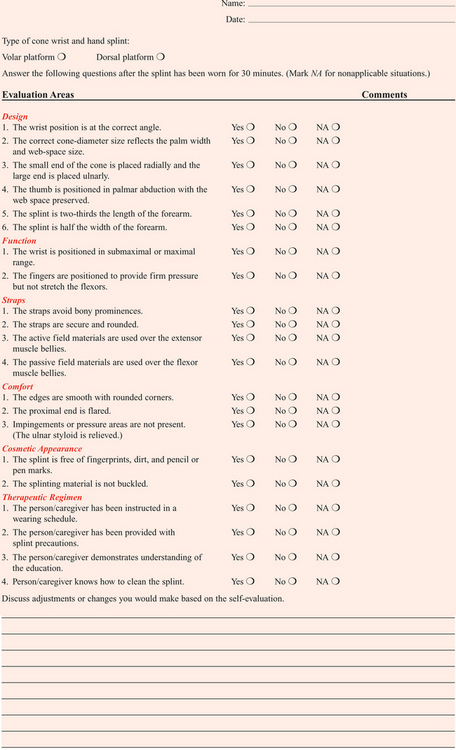

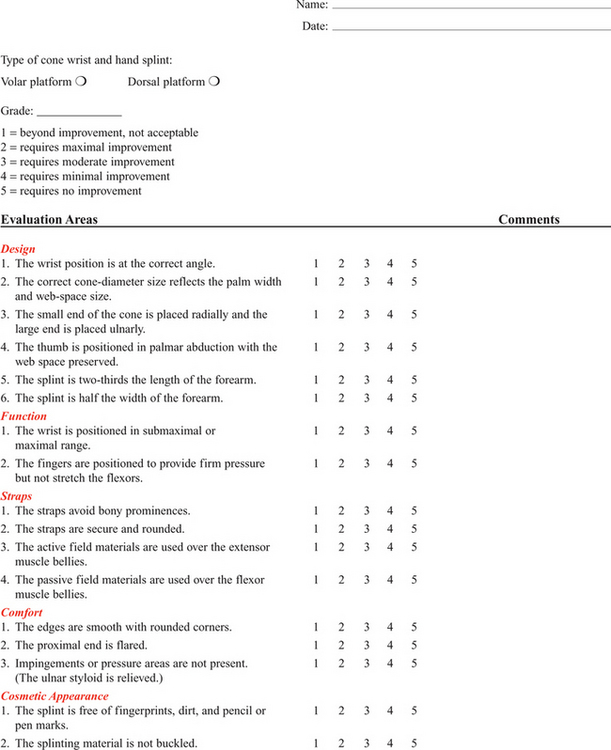

8 Successfully fabricate and clinically evaluate the proper fit of a thermoplastic hard cone.

9 Use clinical judgment to correctly analyze two case studies.

The status of tone-reduction wrist/hand orthotics is like an amorphous quicksand waiting to engulf the unwary therapist. Rehabilitation literature reflects the universal lack of consensus, which Fess et al. [2005, p. 518] summarize with the following statement: “Some physicians and therapists feel strongly that the hypertonic extremity should not be splinted, whereas others are equally adamant that splinting has beneficial results. Even among proponents of splinting, numerous disagreements exist concerning splint design, surface of splint application, wearing times and schedules, joints to be splinted, and specific construction materials for splints and splint components.”

Current professional standards of practice dictate that significant cumulative data and consistent scientific analysis provide the foundation for objective evaluations and treatment protocols. Literature in tone-reduction splinting does not reflect the development of this core body of knowledge. Lannin and Herbert [2003, p. 807] conducted a systematic review of published literature on the use of hand splints following stroke and concluded that there is “insufficient evidence to either support or refute the effectiveness of hand splinting for adults following stroke who are not receiving prolonged stretches to their upper limb.” The paucity of data on the effectiveness of tone-reduction splinting has fostered confusion and contradiction. In the absence of a well-established practice protocol, this chapter is restricted to a discussion of current theoretical and experimental rationales and splint designs. Each practitioner is ultimately responsible for justifying the effectiveness of these techniques in client treatment.

Basmajian et al. [1982, p. 1382] define spasticity as “a state of increased muscular tone with exaggeration of the tendon reflexes.” Clients who have upper motor neuron (UMN) lesions such as cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), closed-head injuries, spinal cord injuries, and cerebral palsy often exhibit spasticity [Bishop 1977]. Spasticity can cause deformity [Bloch and Evans 1977] and limit functional movement [Doubilet and Polkow 1977]. Hand splinting is one treatment technique used to prevent joint deformity and influence muscle tone [Mills 1984].

Historically, experts have documented two major trends in hemiplegic hand splinting. Until the 1950s, the direct application of mechanical force to correct or prevent joint contractures (i.e., biomechanical approach) was the preferred practice in dealing with the effects of spasticity. During the 1950s, emphasis shifted to the underlying causes of spasticity. This viewpoint focuses on the effects of sensory feedback provided by splints in altering muscle tone and promoting normal movement patterns (i.e., neurophysiologic approach) [Neuhaus et al. 1981]. As differing neurophysiologic theories emerged in the 1950s, therapists advocated divergent treatment and splint management principles. At present, several prevalent neurophysiologic rationales recommend a variety of designs composed of a variety of elements related to design position and material options, including the following: (1) platform design, (2) finger and thumb position, (3) static and dynamic prolonged stretch, and (4) material properties.

Some authors have limited their splint designs to one elemental concern, whereas other authors have combined several design elements to support specific treatment rationales. Several commercially available antispasticity hand splints incorporate a variety of design elements. Although this chapter reviews each design element separately, therapists must remember that neurophysiologic splint-design concepts are interrelated and that many splints encompass combinations of design elements.

Forearm Platform Position

A forearm platform is a design element that provides a base of support to control wrist position. Many frequently used tone-reduction splint designs do not affect wrist control but attempt only to influence the digits [Dayhoff 1975, Bloch and Evans 1977, Jamison and Dayhoff 1980, Langlois et al. 1991]. Other designs attempt to influence wrist position but do not address digit position [MacKinnon et al. 1975, Switzer 1980].

Lannin and Herbert [2003, p. 807] stated that “there is insufficient evidence to either support or refute the effectiveness of dorsal or volar hand splinting in the treatment of adults following stroke who are not receiving an upper limb stretching programme.” Isolated joint control constitutes a fundamental design flaw that can produce a predictable outcome because the tendons of the extrinsic flexors cross the wrist, fingers, and thumb. If the digits are positioned in extension, the unsplinted wrist assumes a greater attitude of flexion [Fess et al. 2005]. This compensatory sequence can lead to decreased passive motion and contracture development.

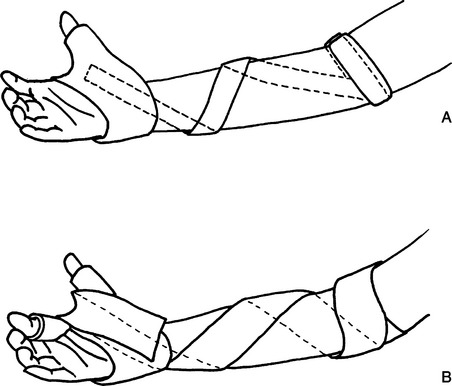

Rehabilitation science literature contains adherents for volar-based forearm platforms [Brennan 1959, Zislis 1964, Peterson 1980] and dorsal-based forearm platforms [Kaplan 1962, Charait 1968, Snook 1979, Carmick 1997]. Other authors report that the two positions are equally effective in tone reduction [McPherson et al. 1982, Rose and Shah 1987].

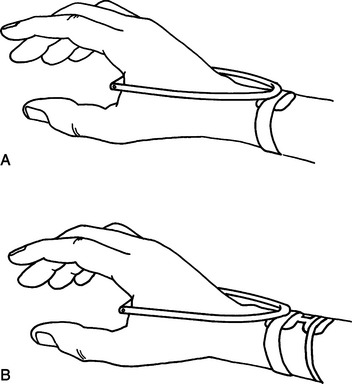

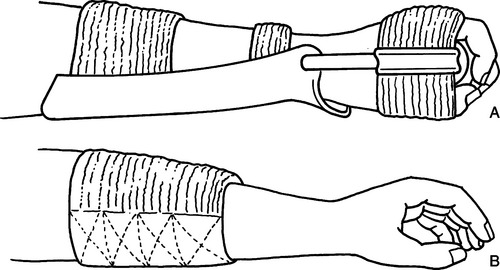

National distributors market ulnar-based platform splints designed to reduce spasticity [Sammons Preston Roylan 2005], although the literature does not appear to mention ulnar-based forearm platforms (Figure 14-1). A therapist can secure all orthotic forearm platforms to the forearm by using straps, resulting in skin contact with volar and dorsal surfaces simultaneously [Rose and Shah 1987, Langlois et al. 1989]. The corresponding cutaneous stimulation provided to flexors or extensors by the forearm platform and straps may be facilitatory or inhibitory. The literature has not yet described research that examines the exact relationship between these variables [Langlois et al. 1991]. These variables are, however, discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 14-1 A hard cone attached to an ulnar platform: spasticity cone splint [Sammons Preston 1995].

Research does not indicate which, if any, of these forearm-platform designs provide the best results to reduce spasticity. However, each forearm-platform design has individual qualities that may be relevant in a clinical decision regarding forearm-platform design. A volar forearm platform that extends into the hand provides greater support for the transverse metacarpal arch. Volar designs do not extend thermoplastic material over the ulnar styloid, thus avoiding the possibility of pressure over this key bony prominence.

A dorsal forearm platform frees the palmar area and enhances sensory feedback. This style is easier to apply and remove if wrist flexion tightness is present. Pressure is also more evenly distributed over the larger thermoplastic surface of the dorsal forearm platform as opposed to the smaller strap surface the volar style provides. An ulnar forearm platform provides a more even distribution of pressure for a client who exhibits a strong component of wrist ulnar deviation with wrist flexion spasticity (Figure 14-1).

Finger and Thumb Position

The finger spreader and hard cone are examples of splint designs based on divergent neurophysiologic treatment theories. Both positioning devices are designed to be adjuncts to specific treatment techniques that promote voluntary hand motion [Bobath 1978, Farber 1982, Davies 1985].

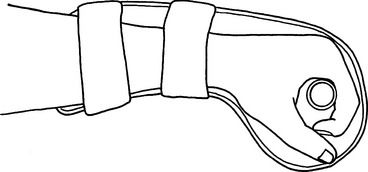

The neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT) theory advocates the use of reflex-inhibiting patterns (RIP) to inhibit abnormal spasticity. Finger and thumb abduction is a key point of control that facilitates extensor muscle tone and inhibits flexor muscle tone [Bobath 1978, Davies 1985]. The finger-spreader design assists in maintaining the reflex-inhibiting pattern.

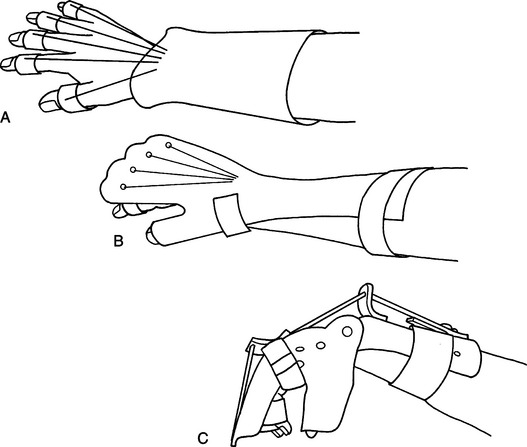

Therapists have constructed recent adaptations of the finger-spreader design from rigid thermoplastic material [Doubilet and Polkow 1977, Langlois et al. 1991]. Bobath’s [1970] original soft foam material has dynamic qualities that are sacrificed when the therapist substitutes rigid, more durable, and cosmetically appealing materials [Langlois et al. 1989] (Figure 14-2). Doubilet and Polkow [1977] state that positioning the thumb in palmar abduction with the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints extended is preferable to radial abduction of the thumb because palmar abduction provides greater fitting security, positions the thumb more comfortably, and produces similar results in spasticity reduction.

Figure 14-2 Finger spreader designs: (A) palmar abduction [Sammons-Preston 2005], (B) radial abduction [Smith & Nephew Rolyan 1998], (C) radial abduction [Sammons-Preston 2005], and (D) palmar abduction [Doubiet and Polkow 1977].

In addition to deciding the thumb position, the therapist considers wrist and interphalangeal joint control. Although some researchers have not extended their RIP designs to include the wrist or interphalangeal joints [Doubilet and Polkow 1977, Langlois et al. 1991], other experts have included extension of the interphalangeal joints of the fingers, thumb, and wrist [Snook 1979, McPherson et al. 1985, Scherling and Johnson 1989]. The resulting design provides a continuous chain of stabilizing forces throughout the wrist and digits. This chain is necessary to prevent compensatory patterns that transfer the forces of spasticity to the unsplinted joint.

Cones

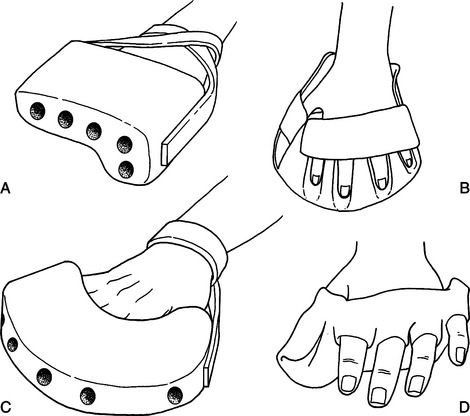

Rood [1954] first advocated the inhibition of flexor spasticity by using a firm cone to provide constant pressure over the palmar surface. The device should provide skin contact over the entire palmar surface for maximal effect but should not apply stretch to the wrist and finger flexor muscles. Farber and Huss [1974] observed that the hard cone has an inhibitory effect on flexor muscles because this device places deep tendon pressure on the wrist and finger-flexor insertions at the base of the palm. Farber [1982] also observed that the total contact from the hard cone provides maintained pressure over the flexor surface of the palm, thus assisting in the desensitization of hypersensitive skin.

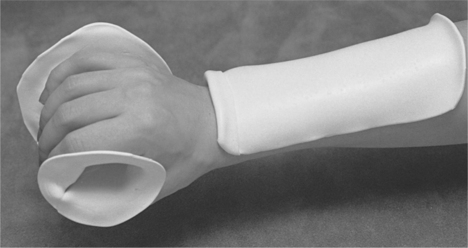

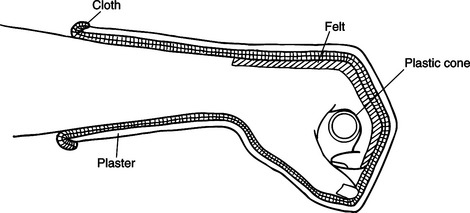

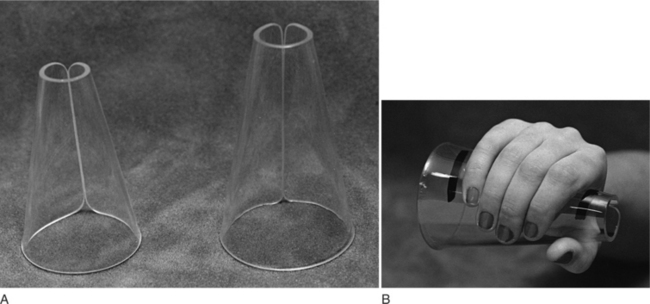

Hard cones are typically constructed of cardboard or thermoplastic material (Figure 14-3). This hollow structure is positioned with the smaller end placed radially and the larger end placed ulnarly to provide maximum palmar contact. Kiel [1974, 1982] recommends the provision of a thenar groove to relieve web-space pressure.

Figure 14-3 Hard-cone designs: (A) hand plastic [Sammons Preston 2005], (B) terry cloth covering [Sammons Preston 2005], and (C) crossover strap system [Contour Fabricator 1983].

Design criteria for hard cones as cited in the literature does not include the use of forearm platforms to control wrist position. Although Kiel [1974] uses a volar platform with a hard cone in the orthokinetic wrist splint (Figure 14-4), the movable wrist joint allows free motion to occur in wrist flexion and extension. Hard cones attached to ulnar platforms (Figure 14-1) are commercially available [Sammons Preston Rolyan 2005], but the literature does not appear to discuss the combination of forearm platforms and hard-cone elements designed to control wrist and finger position.

Figure 14-4 Orthokinetic material placement: (A) orthokinetic wrist splint [Kiel 1974] and (B) forearm cuff [Farber and Huss 1974].

When using a firm cone without a forearm platform, the therapist secures the cone to the hand by using a wide [e.g., 2.5-cm (1-inch)] elastic or nonelastic strap over the dorsum of the hand (Figure 14-4) [Dayhoff 1975, Jamison and Dayhoff 1980]. Dayhoff [1975] reports that contact with soft material on the palmar surface appears to increase flexor tone. This soft stimulus may activate the primitive grasp response [Farber 1982]. Brunnstrom [1970] describes this response as the instinctive grasp reaction. Commercially available soft-palm protectors [Sammons Preston Rolyan 2005] may be contraindicated for clients who exhibit the primitive grasp reaction.

MacKinnon et al. [1975] adapted the standard hard cone to increase sensory awareness and improve hand function. They altered the design from a 4- to 5-cm diameter hollow cone shape to a 0.3- to 1.3-cm diameter cylindrical shape by using a solid wood dowel. Placement of the dowel is critical to design rationale. Pressure over the palmar aspect of the metacarpal heads may be a key to activating hand intrinsics. In response to increased intrinsic activity, muscle tone is reduced in finger flexors and the thumb adductor. Placement of the dowel more distally shifts the maximum contact area from the palm to the metacarpal heads and exposes a larger palmar surface to sensory feedback, thus enhancing awareness and use of the hand.

The original MacKinnon splint incorporates a dorsal forearm platform consisting of a small rectangle of thermoplastic material attached to the dorsum of the wrist with a volar Velcro strap [MacKinnon et al. 1975]. This platform serves as the base for plastic tubing secured to the palmar dowel. The intention of this platform is not to position the wrist forcefully in extension but to position the dowel to apply maximal pressure to the metacarpal heads. Exner and Bonder [1983] enlarged this dorsal forearm platform because it was insufficient to control the forces of marked wrist flexion spasticity. The design alteration relieves skin pressure, provides increased wrist control, and ensures greater comfort (Figure 14-5).

Hard-Cone Splint Construction for the Wrist and Hand

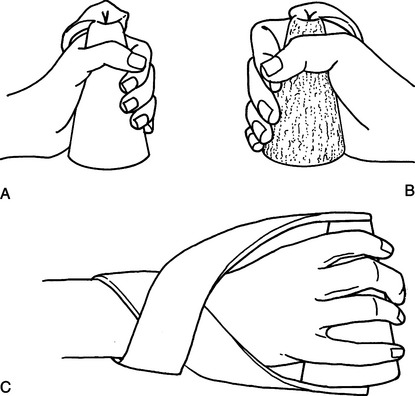

1. Determine the correct cone size by positioning an acrylic cone in the client’s palm. (Use a small Sammons Preston BK-1500 or a large BK-1502 acrylic cone, as shown inFigure 14-6A.) The therapist must establish the correct amount of palm pressure the client can tolerate without application of stretch to the fingers and thumb. Slide the cone onto the client’s hand to determine the correct position (Figure 14-6B).

Figure 14-6 (A) Small and large acrylic hand cones. (B) A hand cone correctly positioned on a client with medial and lateral borders marked.

2. Establish the wrist position by using a goniometer to measure the submaximum or maximum amount of wrist extension the client can tolerate. This measurement must take place while the client wears the acrylic cone (Figure 14-7). Mark on the material the medial and lateral borders of the hand while the cone is positioned in the palm (Figure 14-6B).

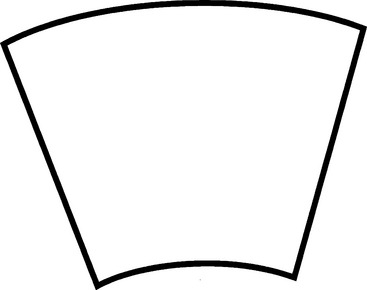

3. Using the template provided (Figure 14-8), trace and cut out the pattern from thermoplastic material (Figure 14-9).

4. Apply dishwashing liquid to the acrylic cone as a parting agent.

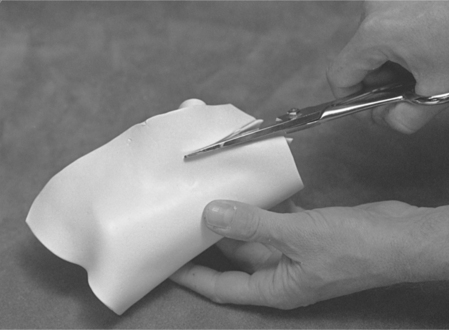

5. Wrap heated thermoplastic material around the cone (Figure 14-10).

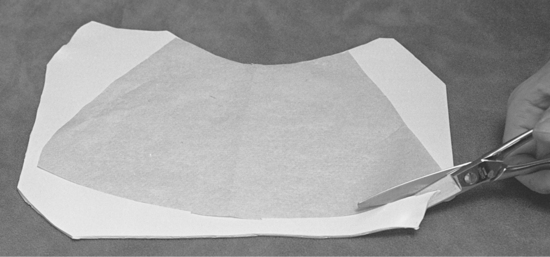

6. Using a sharp pair of scissors, cut the place where the material meets to create a smooth seam edge (Figure 14-11).

7. Slide the thermoplastic cone off the acrylic cone before the material cools to prevent removal difficulty (Figure 14-12).

8. Fit the thermoplastic cone to the client’s hand (Figure 14-13), and mark the following on the cone.

9. Spot heat each of the following areas separately and mold them to the client (Figure 14-14).

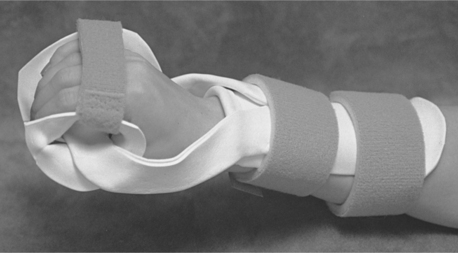

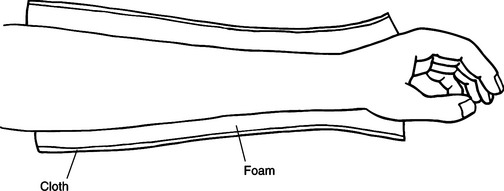

10. Using a paper pattern, fabricate a dorsal forearm platform (Figure 14-15) that is one-half the width of the forearm and two-thirds the length of the forearm.

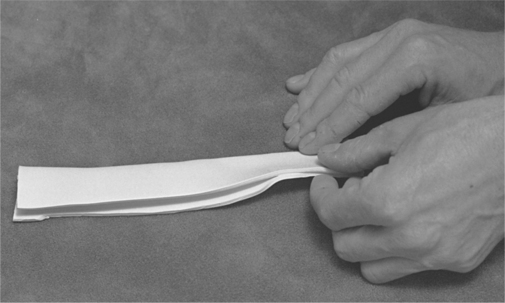

11. Warm two pieces of thermoplastic material that are 2 inches wide and 8 inches long. After doing this, fold and seam the pieces lengthwise to create radial and ulnar supports that connect the forearm platform to the cone (Figure 14-16).

12. Position the completed cone and forearm platform on the client (Figure 14-17), maintaining the wrist in proper alignment.

13. Apply the radial and ulnar supports (Figure 14-18).

14. After the supports have finished cooling, apply two forearm straps and one strap across the dorsum of the hand to complete the splint (Figure 14-19).

15. Use a goniometer to measure the client’s wrist position while the client is secured in the completed orthosis to ensure proper wrist position.

Static and Dynamic Prolonged Stretch

Spasticity is a positive symptom of upper motor neuron lesion damage because it is an exaggeration of normal muscle tone [Tona and Schneck 1993]. Therapists commonly evaluate muscle tone by measuring the amount of resistance a muscle offers to quick-passive stretch or elongation [Trombly and Scott 1989]. Abnormal resistance to passive movement (i.e., stretch reflex) may be a static (i.e., passive) response to the muscle’s maintained state of stretch or a dynamic response to the force and velocity of movement during stretching of the muscle.

The static component (i.e., the nonreflexive, elastic properties of the muscle) and the dynamic component (i.e., the reflexive or active tension of the muscle during stretch) contribute to exaggerated stretch reflex or spasticity [Jansen 1962, McPherson 1981]. The stretch reflex can be triggered at any point of the range-of-motion arc, thus limiting free range of motion. This reflex may also be a significant force to pull the wrist or finger muscles into an abnormal, shortened resting state. This activity creates hypertonus, which is defined as a force of spasticity sufficient to move the limb toward an abnormal resting state [McPherson et al. 1985].

Researchers concur that positioning the wrist and finger flexors in gentle, continuous stretch reduces the passive component of spasticity [McPherson 1981, McPherson et al. 1985, Rose and Shah 1987, Scherling and Johnson 1989]. Some authors recommend a static thermoplastic splint that positions the spastic flexor muscle in less than maximum available passive range of motion (i.e., submaximum range) but beyond the point the stretch reflex is triggered [Peterson 1980, Rose and Shah 1987, Tona and Schneck 1993]. Other authors advocate a static thermoplastic splint that positions the spastic flexor muscle in a fully elongated state (i.e., maximum range) [Farber and Huss 1974, Snook 1979]. Ushiba et al. [2004] reports using a wrist splint to provide prolonged wrist extension. Results of the study indicate inhibitory effects on flexor tone in 82% of the 17 subjects who had spasticity.

A dynamic thermoplastic design is also advocated because it provides a more sustained, consistent stretch to the spastic muscle. The use of an elastic or spring-metal force (Figure 14-20) may ensure slow stretch that does not trigger stretch-reflex receptors [McPherson et al. 1985, Scherling and Johnson 1989].

Material Properties

Dr. Julius Fuchs, an orthopedic surgeon, developed orthokinetic (righting-of-motion) principles in 1927. Some experts have described, refined, and adapted these principles [Blashy and Fuchs 1959; Neeman 1971, 1973; Farber and Huss 1974; Kiel 1974, 1982; Farber 1982; Neeman and Neeman 1984]. The term field refers to material qualities in orthokinetic terminology.

Dr. Fuch’s hand-splint design consists of an orthokinetic tube or cuff (Figure 14-4) that uses dynamic forces to increase range of motion rather than a static device that often contributes to pain and immobilization [Farber and Huss 1974]. The cuff is constructed of an active or facilitatory field the therapist places over the agonist muscle belly. The therapist places the passive or inhibitory field over the antagonist muscle belly. The elastic bandage-material construction of the active field provides minute pinching motions to the dermatome of the agonist muscle (i.e., exteroproprioceptive stimulation) as the muscle contracts and relaxes [Farber 1982]. The inactive field is constructed of layers of elastic bandage sewn or stitched together and provides continuous nonchanging input to the antagonist dermatome.

Because the facilitatory effects of the orthokinetic cuff are activated during the contraction and relaxation of the muscle, this device is most effective when active range of motion is present [Farber 1982]. Other authors recommend alternative materials for construction of inactive fields. Kiel [1974, 1982] uses the unchanging thermoplastic surface of the volar forearm platform in her design of the orthokinetic wrist splint (Figure 14-4). Exner and Bonder [1983] substitute Velfoam as the nonelastic material (Figure 14-5). Kiel [1974, 1982] also suggests that foam lining over a thermoplastic surface transforms that surface from a passive field to an active field as the foam material changes shape to provide facilitatory stimulation.

Serial and Inhibition Casting

Circumferential casting techniques involve specialized fabrication skills and use orthopedic casting materials. Solid serial casting is designed to increase range of motion and decrease contractures caused by spasticity through a series of periodic cast changes. Typically, the affected joint is cast in submaximal range (5 to 10 degrees below maximum passive range). Cast change schedules range from every day for recent contractures to every 10 days for chronic contractures. Blood circulation, edema, skin condition, sensation, and range of motion should be closely monitored during the casting process. The casting program is discontinued when range-of-motion gains are not noted between several cast changes.

Final casts are usually bivalved and applied daily to maintain range-of-motion gains [Feldman 1990]. Therapists routinely use casts to decrease joint contractures. Frequent, periodic cast changes (serial casting) provide prolonged continuous pressure to gradually lengthen muscles and soft tissue. Plaster is a cost-effective choice if the practitioner desires to gradually increase passive range of motion by using a series of static splints. Fiberglass materials are more costly and should not be used without specialized training. King [1982] describes a plaster, serial, dropout cast designed to maintain elbow flexion and stretch and to encourage increased elbow extension (Figure 14-21).

Orthopedic casting materials include plaster or fiberglass bandages that are water activated. Both materials require six to eight layers of thickness for adequate strength, and they harden in 3 to 8 minutes (depending on water temperature). The materials emit heat as a byproduct in the curing process. Plaster splints are not water resistant, do not clean easily, may cause allergic reactions, and pose limitations because of their weight. A plaster bandage is relatively inexpensive, is easy to handle, and conforms/drapes easily to body parts. Fiberglass splints are water resistant, cleanable, lightweight, and not prone to allergic reactions. In addition, fiberglass materials are significantly more expensive and more difficult to handle than plaster. The therapist typically applies several layers of cotton cast padding to the extremity before the application of layers of plaster or fiberglass for skin protection. Specialized casting tools include the following:

Casting program materials include the following:

• Plaster or fiberglass casting tape (2-inch, 3-inch, 4-inch, 5-inch)

• Nylon or cotton stockinette (2-inch, 3-inch, 4-inch, 5-inch)

• Rubber gloves (specialized casting gloves for fiberglass)

Plaster Casting Procedures [Feldman 1990]

1. Measure and record joint range of motion.

2. The client should be sitting or lying comfortably and should be draped with sheets or towels to protect clothing and skin. Explain the procedure to the client clearly and reassure as needed. Some clients with brain injuries may be agitated during the casting procedure.

Premedicating such clients with a sedative can be considered.

3. Tubular stockinette is placed over the extremity to be casted, extending at either end 4 to 6 inches beyond where the cast will end.

4. Determine the targeted position of the extremity. Direct another person (therapist or aid) how and where to hold the extremity.

5. Strips of stick-on foam can be placed on either side of an area that may be susceptible to skin breakdown.

6. Apply cast padding in a taut fashion around the extremity, ending after three or four layers have been applied. Extra padding or felt may be added if needed over bony prominences. Padding is applied 1 to 2 inches above the end of the stockinette.

7. Dip the plaster roll five to six times in warm water. Squeeze excess moisture from the roll.

8. Apply plaster to the extremity in a spiral fashion, moving proximally to distally.

9. Direct the person assisting to stretch the joint minimally as the plaster is being applied. The casting assistant should not apply direct pressure to the plaster as it is setting (breakdown or ischemia inside the cast can occur from this loading point effect). Rather, the assistant should stretch the joint above and below the cast or apply pressure with the entire surface of the hand to evenly distribute pressure.

10. Four to five layers of plaster should be applied. The plaster should be smoothed with the surface using the hand surface in a circular fashion as the plaster sets. Special attention must be paid to smoothing proximal and distal edges to prevent skin breakdown.

11. Before applying the last layer, turn back the ends of stockinette onto the cast. This gives a smooth finished surface to cast edges. Apply the last layer of plaster just below this edge.

12. Instruct the casting assistant to maintain stretch on the joint until the plaster has set (3 to 8 minutes).

13. The plaster will be completely dry in 24 hours. Weight bearing on the casted extremity should be avoided until then.

14. Clean any dripped plaster from the client’s skin, elevate the extremity comfortably, and check either end of the cast for tightness. Check the client’s circulation regularly. Some authors [Copley et al. 1996] recommend a post-casting management program of bivalve splinting in order to maintain increased range of motion and tone reduction.

Fiberglass Casting Procedures [Feldman 1990]

1. Plastic gloves should be worn by anyone touching the fiberglass material during fabrication. Initially and throughout the procedure, the plastic gloves should be coated with petroleum jelly or lotion. Fiberglass adheres to the skin or unlubricated gloves and is difficult to remove. Prepare the limb with padding and stockinette. Practice with the casting assistant to position the joint in the manner desired.

2. Submerge the fiberglass roll in cool water and gently squeeze six to eight times. Remove the roll from the water and apply it dripping wet to the extremity to facilitate handling of the material.

3. Fiberglass roll packages should be opened one at a time and applied within minutes. Fiberglass hardens and does not bond to itself when left exposed to air.

4. Fiberglass must overlap itself by half a tape width.

5. FirBLy blot the exterior of the cast with an open palm in a circular fashion after all layers have been applied. This is to facilitate maximum bonding of all layers. Rubbing in a longitudinal fashion disrupts the fiberglass bond.

6. If one layer of the cast is allowed to cure (harden), subsequent layers do not bond well. All three to four layers should be applied in efficient succession.

7. During the first 2 minutes after immersion, the fiberglass can be molded while the extremity is maintained in the desired position. The extremity should be held stationary during the last few minutes of the 5- to 7-minute setting time.

8. The cast will be completely set in 7 to 10 minutes. It can be removed after that with a cast saw. Cast saws should be operated only by those individuals with training and experience.

The fiberglass cast can be made into a working bivalve in the following manner [Feldman 1990].

1. Using the cast saw, cut the cast into anterior and posterior sections. Remove the cast with the cast spreader.

2. Remove the padding and stockinette from the extremity with the cast scissors and discard them.

3. Inspect both fiberglass shells for protrusions and rough edges. Trim the edges of each shell and file smooth.

4. When the cast padding has been soiled, use cotton padding to reline the shells, taking care to rip padding edges off to provide a smooth inner surface with no ripples. Reline with the same amount of padding used to fabricate the original cast. Extend the padding over all edges and sides of shells.

5. Fold the padding over the edges of the shells and secure with adhesive tape.

6. Cut a length of the stockinette approximately 4 to 6 inches longer than the length of the shell. Line each shell with stockinette. Secure both ends with adhesive tape.

7. Fashion straps using wide webbing and buckles. These can be taped or sewn onto stockinette covering the shell. Bivalves can also be secured with Ace wraps.

8. Carefully wean the client into the bivalve, modifying and adjusting as needed.

Summary: Serial and Inhibition Casting

Therapists also use plaster and fiberglass materials for inhibition or tone-reducing casting. The exact mechanism for the inhibitory effect of these materials is not known [Tona and Schneck 1993]. Gentle, passive stretching and the neutral warmth of the underlying cotton padding may serve as primary relaxing agents [King 1982]. Some authors believe that inhibitive casting materials are more effective than thermoplastic materials at providing deep pressure, prolonged demobilization, neutral warmth, and consistent tactile stimulation [Tona and Schneck 1993]. These authors advocate the use of a separate thermoplastic inhibitive splint (hard cone) incorporated into an inhibitive cast to enhance the tone-reducing effects of both materials (Figure 14-22).

Lower extremity tone-reduction orthotic literature includes the use of a separate footboard as an inhibitive element in the plaster-negative model-casting procedure. The end product of this process is a continuous one-piece thermoplastic orthosis [Hylton 1990]. Current lower extremity tone-reduction orthotic literature focuses on the incorporation of various inhibitive and facilitatory design elements into one total-surface-contact thermoplastic splint [Lohman and Goldstein 1993].

Other Materials

Authors have reported the spasticity-reduction effectiveness of other materials that provide neutral warm and passive stretch. Pneumatic-pressure arm splints that are orally inflatable (Figure 14-23) are especially effective as adjuncts to upper extremity weight bearing [Bloch and Evans 1977; Johnstone 1981; Poole et al. 1990, 1992; Lofy et al. 1992]. These tubular devices are open at the distal end, allowing the therapist to place the client’s wrist and hand into the desired position of extension. Wallen and O’Flaherty [1991] have devised a cylindrical foam splint (Figure 14-24) that reduces the muscle tone of the upper extremity. The foam material reacts dynamically and automatically adjusts to greater degrees of extension. Mackay and Wallen [1996] report a significant increase in passive elbow extension after use of soft foam splint.

Elastic tubular bandages have been successful in providing relaxation of upper extremity hypertonicity through the application of neutral warmth and deep pressure [Johnson and Vernon 1992]. Takami et al. [1992] describe the use of a titanium metal alloy that gradually changes shape in response to room temperature and provides gentle passive stretch to spastic wrist flexors. In addition, neoprene material provides a dynamic force that produces gentle stretch. The neoprene thumb abduction supination splint (TASS) (Figure 14-25) facilitates key-point positioning of the upper extremity, thus reducing spasticity [Casey and Kratz 1988]. Gracies et al. [2000] report success in reducing wrist and finger flexor spasticity using a Lycra sleeve and glove. Lycra is thinner than neoprene but provides a similar dynamic force, thus promoting gentle stretch.

1. How do the biochemical and neurophysiological approaches to hand splinting differ?

2. What are the strengths and weaknesses of dorsal versus volar forearm platform?

3. What are the three rationales supporting the use of the finger spreader and the hand cone?

4. Why are passive and dynamic components of spasticity critical in splint design?

5. What are the two major components of other kinetic splinting?

6. What are two major characteristics for each of the below materials?

References

Basmajian, J, Burke, M, Burnett, G, Campbell, C, Cohn, W, Corliss, C, et al. Illustrated Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, Twenty-fourth Edition. London: Williams & Wilkins, 1982.

Bishop, B. Spasticity: Its physiology and management. Part III. Identifying and assessing the mechanisms underlying spasticity. Physical Therapy. 1977;57:385–395.

Blashy, MRM, Fuchs (Neeman), RI. Orthokinetics: A new receptor facilitation method. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1959;13:226–234.

Bloch, R, Evans, M. An inflatable splint for the spastic hand. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1977;58:179–180.

Bobath, B. Adult Hemiplegia: Evaluation and Treatment. London: William Heinemann, Medical Books, 1970.

Bobath, B. Adult Hemiplegia: Evaluation and Treatment. London: William Heinemann, Medical Books, 1987.

Brennan, J. Response to stretch of hypertonic muscle groups in hemiplegia. British Medical Journal. 1959;1:1504–1507.

Brunnstrom, S. Movement Therapy in Hemiplegia. New York, Evanston, and London: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1970.

Carmick, J. Case report: Use of neuromuscular electrical stimulation and a dorsal wrist splint to improve the hand function of a child with spastic hemiparesis. Physical Therapy. 1997;77(6):661–671.

Casey, CA, Kratz, EJ. Soft splinting with neoprene: The thumb abduction supinator splint. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1988;42(6):395–398.

Charait, S. A comparison of volar and dorsal splinting of the hemiplegic hand. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1968;22:319–321.

Copley, J, Watson-Will, A, Dent, K. Upper limb casting for clients with cerebral palsy: A clinical report. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1996;43:39–50.

Davies, P. Steps to Follow: A Guide to the Treatment of Hemiplegia. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1985.

Dayhoff, N. Re-thinking stroke soft or hard devices to position hands. American Journal of Nursing. 1975;75(7):1142–1144.

Doubilet, L, Polkow, L. Theory and design of a finger abduction splint for the spastic hand. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1977;32:320–322.

Exner, C, Bonder, B. Comparative effects of three hand splints on bilateral hand use, grasp, and arm-hand posture in hemiplegic children: A pilot study. Occupational Therapy Journal Research. 1983;3:75–92.

Farber, SD. Neurorehabilitation: A multidisciplinary approach. Toronto: WB Saunders, 1982.

Farber, SD, Huss, AJ. Sensorimotor Evaluation and Treatment Procedures for Allied Health Personnel. Indianapolis: Indiana University Foundation, 1974.

Feldman, PA. Upper extremity casting and splinting. In: Glenn MD, Whyte J, eds. The Practical Management of Spasticity in Children and Adults. Malvern, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1990.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand and upper extremity splinting: principles and methods. St. Louis: Elsevier/Mosby, 2005.

Fuchs, J. Technische Operationen in der Orthopaedie Orthokinetik. Berlin: Verlag Julius Springer, 1927.

Gracies, J-M, Marosszeky, JE, Renton, R, Sandanam, J, Gandevia, SC, Burke, D. Short-term effects of dynamic lycra splints on upper limb in hemiplegic patients. Archives Physical Medical Rehabilitation. 2000;81:1547–1555.

Hylton, NM. Postural and functional impact of dynamic AFOs and FOs in a pediatric population. Journal of Prosthetic Orthotics. 1990;2(1):40–53.

Jamison, S, Dayhoff, N. A hard hand-positioning device to decrease wrist and finger hypertonicity: A sensorimotor approach for the client with non-progressive brain damage. Nursing Research. 1980;29:285–289.

Jansen, JKS. Spasticity: Functional aspects. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1962;38(3):41–51.

Johnson, J, Vernon, DC. Elastic tubular bandages: An adjunctive treatment approach to abnormal muscle tone. Gerontology Special Interest Selection Newsletter. 1992;15(2):3–4.

Johnstone, M. Control of muscle tone in the stroke client. Physiology. 1981;67:198.

Kaplan, N. Effect of splinting on reflex inhibition and sensorimotor stimulation in treatment of spasticity. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1962;43:565–569.

Kiel, J. Dynamic Orthokinetic Wrist Splint: Sensorimotor Evaluation and Treatment Procedures. Indianapolis: Indiana-Purdue University, 1974.

Kiel, J. Orthokinetic Wrist Splint for Flexor Spasticity: Neurorehabilitation. Toronto: W. B. Saunders, 1982.

King, T. Plaster splinting as a means of reducing elbow flexor spasticity: A case study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1982;36:671–674.

Langlois, S, MacKinnon, JR, Pederson, L. Hand splints and cerebral spasticity: A review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1989;56(3):113–119.

Langlois, S, Pederson, L, MacKinnon, JR. The effects of splinting on the spastic hemiplegic hand: Report of a feasibility study. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;58(1):17–25.

Lannin, NA, Herbert, RD. Is hand splinting effective for adults following stroke? A systematic review and methodological critique of published research. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2003;17:807–816.

Lofy, S, Pereida, L, Spores, M. Air splints: Technique propels stroke rehab. Occupational Therapy Week. 1992;6(18):18–19.

Lohman, M, Goldstein, H. Alternative strategies in tone-reducing AFO design. Journal of Prosthetic Orthotics. 1993;5(1):21–24.

Mackay, S, Wallen, M. Re-examining the effects of the soft splint on acute hypertonicity at the elbow. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1996;43:51–59.

MacKinnon, J, Sanderson, E, Buchanan, D. The MacKinnon splint: A functional hand splint. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1975;42:157–158.

McPherson, J. Objective evaluation of a splint designed to reduce hypertonicity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1981;35:189–194.

McPherson, J, Becker, A, Franszczak, N. Dynamic splint to reduce the passive component of hypertonicity. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1985;66:249–252.

McPherson, J, Kreimer, D, Aalderks, M, Gallager, T. A comparison of dorsal & volar resting hand splints in the reduction of hypertonus. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1982;36:664–670.

Mills, V. Electromyographic results of inhibitory splinting. Physical Therapy. 1984;64:190–193.

Neeman, RL. Technique of preparing effective orthokinetic cuffs. Bulletin on Practice (AOTA). 1971;6(1):1.

Neeman, RL. Orthokinetic sensorimotor treatment. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1973;20:122–125.

Neeman, RL, Neeman, M. Comments on orthokinetics. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 1984;4:316–318.

Neuhaus, B, Ascher, E, Coullon, B, Donohue, MV, Einbond, A, Glover, J, et al. A survey of rationales for and against hand splinting in hemiplegia. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1981;35:83–90.

Peterson, LT. Neurological Considerations in Splinting Spastic Extremities. Menomonee Fall, WI: Rolyan Orthotics Lab, 1980.

Poole, JL, Whitney, SL, Hangeland, N, Baker, C. Function in stroke clients. Occupational Therapy Journal Research. 1990;10:360–366.

Poole, JL, Whitney, SL, Haworth, PR. Treatment for individuals with stroke. Physical and Occupational Therapy Geriatrics. 1992;11:17–27.

Rood, M. Neurophysiological reactions as a basis for physical therapy. Physical Therapy Review. 1954;34:444–449.

Rose, V, Shah, S. A comparative study on the immediate effects of hand orthoses on reduction of hypertonus. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1987;34(2):59–64.

Sammons-Bissell Health Care Corporation (1995) Catalog. Western Springs, IL.

Sammons Preston Roylan (2005) Catalog. Western Springs, IL.

Scherling, E, Johnson, H. A tone-reducing wrist-hand orthosis. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1989;43(9):609–611.

Smith & Nephew Rolyan, Inc. (1998) Catalog. Menomonee Falls, WI.

Snook, JH. Spasticity reduction splint. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1979;33:648–651.

Switzer, S. The Switzer splint. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1980;43:63–64.

Takami, M, Fukui, K, Saitou, S, Sugiyama, I, Terayama, K. Application of a shape memory alloy to hand splinting. Prosthetic Orthotics International. 1992;16:37–63.

Tona, JL, Schneck, CM. The efficacy of upper extremity inhibitive casting: A single subject pilot study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1993;47(10):901–910.

Trombly, C, Scott, A. Occupational Therapy for Physical Dysfunction, Third Edition. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1989.

Ushiba, J, Masakado, Y, Komune, Y, Muraoka, Y, Chino, N, Tomita, Y. Changes of reflex size in upper limbs using wrist splint in hemiplegic patients. Electromyography Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;4:175–182.

Wallen, M, O’Flaherty, S. The use of soft splint in the management of spasticity of the upper limb. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1991;38(15):227–231.

Zislis, J. Splinting of hand in a spastic hemiplegic client. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1964;45:41–43.