Chapter 2 A history of the midwifery profession in the United Kingdom

After reading this chapter, you should be able to appreciate:

The office of midwife: a female domain

The office of midwife is a truly ancient calling. Sculptures of midwives attending birth date back at least 8000 years and the old Egyptian fertility goddess, Hat-hor, was frequently portrayed in this role. Midwives appear, too, in the Old Testament; the quick-witted Shiprah and Puah outmanoeuvre Pharaoh, and the birth of Tamar’s twins testifies to the midwife’s resourcefulness and skill.

Until early modern times, childbirth was considered a female province, of which women alone had special understanding. No word existed in any language to signify a male birth attendant, and when these appeared in the late 16th century, new terms had to be created. The Anglo-Saxon ‘midwife’, or ‘with-woman’, denotes the office of being with the labouring woman. Other titles like the old French ‘leveuse’ and the German ‘hebamme’ imply her function of receiving the child. The later French usage, ‘sage-femme’ (wise-woman), implies wider concerns and, indeed, midwives were commonly consulted on matters of fertility, female ailments, and care of the newborn.

Occasionally, when instruments were necessary to extract the child, a man might be called in. Traditionally, their use belonged to surgeons, who, with the increasing exclusion of women from medicine and surgery from the 1300s, were overwhelmingly men. Yet the surgeon’s scope was limited. Using hooks and knives, he might extract piecemeal an infant presumed dead or, hoping to save its life, swiftly perform a caesarean section on the newly dead mother. Hence a man’s advent into the birth chamber usually presaged the death of mother or child, or both. Where surgeons were not available, however, midwives themselves might undertake such operations. In wealthy households, a physician (a university-educated practitioner of internal medicine), whose midwifery knowledge came from classical writings rather than practical experience, might be called to prescribe medicines judged necessary for mother or child.

What manner of women were midwives?

Little is known about individual European midwives before the 16th century. As later, they would be married women or widows, generally of middle age or older. Most would have given birth, since until the late 1700s this experience, except for daughters following their mothers into the work, was usually considered essential. What formally educated midwives there were came generally from the artisan class or lower gentry. Such women invested time and money in several years’ apprenticeship to a senior midwife, and by the 17th century most would be literate. These midwives would mostly be found in towns, where there was sufficient prosperity to make their outlay worthwhile. Most would start by practising among the poor, possibly acquiring a more affluent clientèle as their reputation grew. Town midwives engaged by country nobility or gentry would arrive well beforehand, and stay several days or weeks afterwards, being recompensed accordingly. Attendance on royalty was the greatest prize. In 1469, Margaret Cobb, midwife to Edward IV’s queen, received in addition to her fee a life pension of £10 a year, as did Alice Massey, who attended Elizabeth of York in 1503. Mme Peronne, who in 1630 travelled from France to attend Charles I’s French queen, was paid £300, with £100 for her expenses.

These midwives, however, were in a minority. Inevitably the rest attended only the poor (the majority of the population), many living in rural, perhaps isolated, places. Such women would learn their midwifery through their own and their neighbours’ birthing experiences, undertaking the work by virtue of their seniority or the large number of children they had borne (McMath 1694; Siegemundin 1690, preface). Their work might entail travelling long distances on foot to outlying habitations, for a few pence or a small payment in kind. Many such women took up the work from necessity, eking out a poor living with sick nursing and laying out the dead, as did their successors until the early 20th century.

Midwifery knowledge

Before the 16th century, most midwifery knowledge, like knowledge in other fields, would be transmitted by word of mouth and by example. The first midwifery manual printed in English appeared in 1540 – The Byrth of Mankynde, translated via Latin from a 1513 German work by Eucharius Roesslin, City Physician of Wurms. Drawn largely from ancient and mediaeval texts, the Byrth included many of their errors, thus demonstrating the ignorance of practical midwifery then general among physicians. Yet it contained much good sense on the care of the labouring woman, together with directions for managing abnormal cases, including delivery of the infant by the feet, instrumental removal of the dead fetus and caesarean section on the dead mother. However, although addressed to pregnant women and midwives, the work could only benefit the literate minority who could afford to buy it.

‘In the straw’

Generally, birth took place at home, poorer women typically delivering in the communal room, before the hearth, the floor covered with straw which would later be burnt. Usually the birth chamber was darkened, windows and doors sealed, with a fire kept burning for several days. These precautions were taken lest the woman took ‘cold’ (developed the possibly lethal ‘childbed fever’), and in more superstitious households for fear that malevolent spirits might gain entrance, harming mother or infant (Gélis 1996:97, Thomas 1973:728–732). Care was taken, too, that the afterbirth and its attachments (all credited with powerful magical properties) were disposed of safely, lest they be used in spells to harm the family. These beliefs were still current in remote parts of Europe in the early 20th century.

To hasten matters on in early labour the parturient would periodically be encouraged to walk, supported by two sturdy women, her strength sustained by warm broth or spicy drinks. The midwife, sharing the universal and time-honoured belief that the child provided the motive power for its birth, would follow ancient practice in greasing and stretching the woman’s genitalia and dilating the cervix to ‘help’ the infant emerge. Hence the ‘ideal’ midwife possessed, along with appropriate qualities of character, small hands with long tapering fingers (Temkin 1956).

The second stage of labour usually took place, as for millennia, with the woman in an upright or semi-upright position (Kuntner 1988). In rich households a birth chair might be used, but more commonly the parturient sat on a woman’s lap. Some women knelt or stood, leaning against a support; some adopted a half-sitting, half-lying posture, with a solid object to push their feet against during contractions, while others delivered on all fours (Blenkinsop 1863:8,10,73, Gélis 1996:21–36). As labour progressed, the woman would instinctively change position, ‘as shall seeme commodious and necessarye to the partie’, as the Byrth put it, urging the midwife to comfort her with refreshments and encourage her with ‘swete wurdes’ (see Fig. 2.1). Following delivery, the mother would be put to bed to ‘lie in’ – rich women for up to a month, the poor for days at most. The infant would be washed, then swaddled to ‘straighten’ its limbs, and if circumstances permitted, an all-woman celebration of this female life event would ensue.

Figure 2.1 Midwife attending a labouring woman seated on a birth chair. Two women hold her shoulders firmly while the midwife carries on with her work. The midwife’s sponge, with scissors and thread for cutting and tying the cord, lie in readiness by the rear wall.

(From Rueff, Jacobus: Ein schön lustig Trostbüchle von den Empfengknussen und Geburten der Menschen, Zurich, 1554 (Wellcome Library, London).)

The midwife, the church and the law

The midwife’s duties did not end with the birth, however. In pre-Reformation times, she carried heavy responsibilities for the salvation of the infant’s soul, being required to take weakly infants directly to the priest for baptism. If death seemed imminent, she should perform the ceremony herself, taking care on pain of severe punishment to use only the Church’s prescribed words. If the woman died undelivered, she was immediately to open the body, and if the infant were alive, to baptise it. Stillborn infants, in their unhallowed state unfit for Christian burial, she was to bury in unconsecrated ground, safely and secretly, where neither man nor beast would find them. Baptism would generally take place within a week of birth, and the midwife, infant in arms, headed the procession to the church, the mother remaining in seclusion until she had been ‘churched’. The midwife enjoyed an honoured place at post-christening celebrations and in prosperous households would be liberally tipped by family and friends (see Fig. 2.2). Later, after the lying-in period, she would accompany the mother to her ‘churching’ – originally a ‘purification’ ceremony, but under Protestantism merely one of maternal thanksgiving.

Figure 2.2 Frontispiece from Jane Sharp’s Compleat Midwife’s Companion, 1724, showing the midwife handing the mother a bowl of broth following the birth; later, infant in arms, she heads the christening procession to the church, subsequently appearing as a guest at the christening feast where she will receive substantial tips from the assembled company. The mother is not present, being still in seclusion in the lying-in room until her churching some weeks later.

(Wellcome Library, London)

The midwife also had an important role in legal matters. Where a woman condemned to death pleaded pregnancy in the hope of postponing or mitigating punishment, a panel of midwives would be summoned to examine her, though some post-execution dissections demonstrated these examinations’ unreliability (Pechey 1696:55–56). Midwife panels were also called to examine unmarried women alleging rape, women accused of aborting themselves or of concealing the birth (and possible murder) of an unwanted infant, or determine the alleged prematurity of infants born within less than 9 months of marriage. Midwives attending an unmarried woman were also expected to make her name the father, lest he escape the Church’s punishment for fornication and his responsibility to the parish for the child’s upkeep.

Governing the midwife

In view of these religious and legal duties, the midwife’s character and religious orthodoxy were inevitably of concern to the Church. In 1481, Agnes Marshall of Emeswell, Yorkshire, was ‘presented’ at the Bishop’s Court, not because she lacked skill in midwifery, but because she used (pagan) ‘incantations’ to ‘help’ the labour. Midwives were suspect, too, because of their access to stillbirths, allegedly used in devil-worship. In 1415, a successful Parisian midwife, Perette, was turned in the pillory and banned from practice for supplying a tiny fetus used, unbeknownst to her, in sorcery. On account of her great skill, however, she was restored to practice by order of the King.

Probably the first system of compulsory midwife licensing in Europe was instituted in the city of Regensberg in Bavaria in 1452, a system gradually emulated in other European cities. Applicants for a licence were commonly examined by a panel of physicians, who, innocent of practical midwifery, based their examination on classical texts. Generally, midwives were required to send for a physician or surgeon in difficult cases, and in Strasbourg, midwives were prohibited from using hooks or sharp instruments on pain of corporal punishment. Many cities appointed midwives to serve the poor, supplementing their remuneration with payment in kind and providing financial aid in old age or disability (Gélis 1988:25, Wiesener 1993:78–84).

In England, the first arrangements for formal control of midwives were made under the 1512 Act for regulating physicians and surgeons. The Act’s aim was to limit unskilled practice and prevent the use of ‘sorcery’ and ‘witchcraft’ in medicine. It therefore provided for Church Courts to license practitioners able to produce testimony to their skill and religious orthodoxy, and to prosecute the rest. A midwife applying for a licence would normally bring to the Court a reference from the local parson, together with ‘six honest matrons’ she had delivered, to testify to her competence. There was, however, no formal examination on this point as existed under Continental schemes.

Successful applicants swore a long and detailed oath, promising ‘faithfully and diligently’ to help childbearing women, to serve ‘as well poor as rich’, not to charge more than the family could afford, nor divulge private matters. They swore not to use ‘sorcery’ to shorten labour; to use only prescribed words when christening infants; and to bury as directed all stillborn children. They undertook not to procure abortion nor connive at child destruction, false attribution of paternity or substitution of infants. Neither were they to allow any woman to be delivered secretly, and always, if possible, see that lights were available and ‘two or three honest women’ present, a requirement clearly aimed at preventing the speedy suffocation of an unwanted child.

Advent of the man-midwife

Around the mid-16th century came other changes laden with import for midwives, as surgeons, inspired by the new Renaissance spirit of enquiry, turned their attention to the anatomy of childbirth. Outstanding in this field was the French barber-surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510–1590), notable for his description in his 1549 Briefve Collection of the use of podalic version in malpresentation cases. The success of men like Paré was to encourage the extension of male attendance from ‘extraordinary’ to routine cases. This development gradually spread throughout Europe, being recognized around 1600 in Britain with the new term ‘man-midwife’, and in France that of ‘accoucheur’.

The centrality of anatomical knowledge to good midwifery was well understood by leading practitioners, men and women. The London midwife Jane Sharp began her 1671 ‘Midwives Book’ by deploring ‘the many Miseries’ women endured at the hands of midwives who practised ‘without any skill in Anatomy…merely for Lucres sake’. Her contemporary, the Derbyshire man-midwife Willughby, concurred, finding that many country midwives could not manage malpresentations, however also condemning inexperienced young surgeons and ill-prepared apothecaries, whose ‘fatal bunglings’ deserved the branding-iron or the hangman’s noose.

Maternal mortality

Given the general lack of statistics, the extent of contemporary maternal mortality (calculated as death at or within the month after the birth) is impossible to discover. However, in his 1662 study of the London Bills of Mortality, John Graunt estimated maternal mortality in London at about 15 per 1000 births. Those dying from the ‘hardness’ of their labour, as distinct from other causes, he put at less than 1 in 200 (5 per 1000). Significantly, along with other authorities, Graunt believed that poor hard-working countrywomen did best in childbirth. The celebrated Dr Harvey went further. Challenging the general practice of dilating the parturient’s vulva and os uteri, he argued that women delivering unattended fared best, since Nature, escaping the midwife’s interventions, was allowed unhindered to take her course. His friend Willughby confessed himself converted to this view, condemning interference in all but abnormal cases, as always harmful

Interestingly, Willughby also links such interference with the woman ‘taking cold’ (Blenkinsop 1863:6), a likely reference to ‘puerperal’ fever, not so named, but recognized under ‘fevers’ and ‘agues’ occurring after childbearing. Following ancient humoral theory, the condition was ascribed to a bodily ‘humours’ imbalance (Jonas 1540: xxxiii, Sharp 1671:243–250) and was probably then, as later, the chief single cause of maternal death. Not until the late 18th century was it publicly proposed that this deadly malady might be carried to the woman on the attendants’ clothing or unwashed hands (Gordon 1795:98–99), a view not completely accepted, even in medical circles, until the 1940s.

Midwives under threat

When urging midwives to study anatomy, Jane Sharp had recognized that women’s exclusion from the universities and ‘schools of learning’, where this was taught, disadvantaged them compared with men. Girls were barred, too, from grammar schools, which taught Latin, knowledge of which was the mark of an educated person and which was still used for many medical texts. Leading male practitioners therefore enjoyed higher social status than midwives, however successful. Although in 1762 Mrs Draper delivered the future George IV, with Dr Hunter and the surgeon Caesar Hawkins waiting elsewhere, Hunter’s diary makes their relative ranking clear (Stark 1908). Moreover, the distinction of great 18th-century practitioners like Manningham, Ould, Hunter and Smellie was to reflect credit on every man-midwife, deserved or not.

However, it was probably the general introduction in the 1720s of the midwifery forceps that precipitated the rapid acceleration of the existing trend. The forceps enabled the delivery of live infants where previously child or mother might have been lost, and the shortening of tedious labour. Since custom discouraged use of instruments by midwives, this development further enhanced the position of men and many surgeon-apothecaries, taking up midwifery, became general practitioners in fact if not yet in name. Some men-midwives, too, saw childbirth as a mechanical process and themselves, with their right to use instruments, as better suited to preside over it. Indeed, for many, the educated male practitioner represented the new enlightened age, while midwives, whose ranks included many ignorant, illiterate and superstitious women, appeared relics of a benighted past.

Keenly aware of the threat to their livelihood, midwives fought back, supported in books and pamphlets by both medical and lay sympathizers. For reasons of modesty, these argued, many women would not send for a man, nor would their husbands allow it. Many could not afford men’s fees, and male assistance, especially in the country, was commonly unavailable. Men-midwives, it was contended, resorted to unnecessary use of instruments in order to save their time and increase their fees, and were thus responsible for increased maternal and infant mortality. Furthermore, they exaggerated the dangers of childbirth, frightening women into believing that extraordinary measures, and therefore male attendance, were more necessary than they actually were. Also, by insisting on being called to every ‘trifling’ difficulty, men were reducing midwives to ‘mere nurses’, while taking every opportunity to denigrate their competence and blame them, however unjustly, for any mishap, even if caused by themselves.

Lying-in hospitals and ‘out-door’ charities

One champion of the midwives’ cause was the London surgeon John Douglas. Writing in 1736 to rebut men-midwives’ claims that difficult births were beyond female capacities, he instanced the career of Mme du Tetre, lately Head Midwife at the great Paris hospital the Hôtel-Dieu. Douglas maintained that if English midwives had the same opportunities as Frenchwomen (the Hôtel-Dieu had trained midwives since 1631), they could reach equally high standards. British counterparts of such hospitals had been abolished in Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, and Douglas, seeing lying-in hospitals as essential to improved midwife instruction, demanded their establishment in all the principal English cities. The first such permanent foundation, however, was the Dublin ‘Rotunda’, established in 1745. Two lying-in wards were created in the Middlesex Hospital in 1747, and four (tiny) lying-in hospitals opened in London shortly afterwards. Similar institutions appeared in major provincial cities as the century progressed.

These hospitals, like others founded at the time, were charitable institutions, funded by the subscriptions of the wealthy for the benefit of the poor (in this case ‘respectable’ poor married women), and run by voluntary lay boards. Hospitals were a mixed blessing for the women attended there. Outbreaks of puerperal fever, a regular feature until the adoption of antiseptic practice in the late 19th century (and occurring sporadically even in the 1930s), boosted death rates and necessitated closure for weeks on end. Safer and cheaper were ‘out-door’ charities, such as the Royal Maternity Charity, London (founded 1757). These provided poor women with midwife attendance at home, with designated medical assistance as necessary, and probably trained far more midwives than the tiny hospitals. There was, however, no move in England from government, central or local, on this vital matter of midwife instruction. By this time, Bishops’ licensing – which although no great guarantee of skill, and never properly enforced, had given the licensed midwife some status – was generally defunct.

Continental comparisons

Meanwhile, on the Continent, state control in matters perceived to be in the public interest, including midwife instruction and regulation, grew ever stronger. Many German towns had midwife schools and ‘midwife-masters’ to teach midwives. In 1759 the French King sent the eminent midwife Mme du Coudray around the country to lecture to midwives and surgeons, and to found lying-in hospitals. Educated English midwives, realizing that lack of official instruction and regulation at home was hastening the midwife’s decline, called vainly for Continental-style systems in England. Scotland, where Continental influence was stronger, was different. In 1694 Edinburgh Town Council had established a system of midwife regulation and in 1726 appointed an honorary Professor of Midwifery, Joseph Gibson, for their instruction. In 1740 the Glasgow Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons instituted a similar system for the city and surrounding counties, which, like Edinburgh’s, appears to have operated throughout the century.

’Towards a complete new system of midwifery’

By the mid-18th century, male practitioners, disdaining the familiar ‘man-midwife’, began to adopt the French term ‘accoucheur’, as conveying greater status. Their approaches to delivery varied, however. Some still dilated the cervix and the labia vulvae, practices continuing among the more ignorant at the century’s close (Clarke 1793:21). Some extracted the placenta immediately after delivery by introducing the hand into the uterus, while others roundly condemned this (Smellie 1752–64:238–239). The general trend, however, was towards less intervention. This development stemmed from the new realization that it was not exertions by the child but uterine muscular action that provided the necessary expulsive force (ibid. 202). Significantly, Smellie (since regarded as the ‘father of British obstetrics’) concluded from his vast experience that, out of 1000 parturients, 990 would be safely delivered ‘without any other than common assistance’ (ibid. 195–196).

Though ambulation in the first stage was still encouraged, women’s freedom to choose their delivery position was gradually being curtailed. Earlier authorities, male and female, had encouraged women to adopt the position most comfortable to them as facilitating the best outcome for mother and infant. Smellie underlined the advantages of upright positions in furthering labour, partly through gravity, and partly through the ‘equalisation of the uterine force’, recommending them for ‘tedious labours’ (ibid. 202). Yet, along with other authorities, Smellie generally advised delivery in bed (half-sitting, half-lying) for fear that otherwise the woman might take ‘cold’, and hence develop ‘childbed fever’ (ibid. 204). Others, like Dr John Burton of York, favoured the ‘dorsal’ and ‘left lateral’ positions as ‘easiest for the Patient and most convenient for the Operator’ (Burton 1751:106–107). Indeed, sitting by the edge of the bed, his hand concealed under the sheet, was less tiring and less undignified for men hoping for recognition of their art as part of medicine proper, than was crouching at the woman’s knees on the midwife’s low stool (see Fig. 2.3).

Figure 2.3 A man-midwife attends a birth in Holland. The parturient is now labouring in bed. Although in a semi-upright position she has lost some of the benefits of being fully upright, with her feet on the floor, in aiding her expulsive efforts. She holds on to her attendants’ shoulders while they push against her feet to give her some purchase for her pushing. To protect the woman’s modesty the corners of a sheet are pinned around the man-midwife’s neck so that he perforce works blind, a situation that sometimes led to error.

(From S. Janson, Korte en Bonding verbandeling, van de voortteelingen’t Kinderbaren, Amsterdam 1711 (Wellcome Library, London))

Recumbent delivery positions gradually became the norm for ‘civilised’ practice. Although delivery out of bed was to continue in rural areas into the 20th century, it was generally considered low class, if not inhumane. Significantly, the parturient’s transfer to bed, together with her increasing designation as a ‘patient’ (a word originally used only of the sick), indicated her transition from an active to a passive role in this important life-event, and, implicitly, the growing medicalization of childbirth itself.

The decline of the midwife

By the early decades of the 19th century the midwife’s situation had deteriorated still further. Growing prudery, largely the result of the Evangelical movement, had rendered reference to childbirth, and even the word ‘midwife’, taboo in polite society. Together with the male capture of the wealthier private practice and the growing reluctance of the middle classes to allow their women to work, this prudery meant that fewer educated women were entering midwifery, leaving many who wanted skilled assistance in childbirth forced to send for a man. Midwife supporters argued that midwives’ instruction (where it existed) had not kept pace with men’s and increasingly calls arose for the better education of female practitioners to the highest professional standards, in midwifery and women’s diseases. The medical response was predictable. Women were unfitted by nature for ‘scientific mechanical employment’ (which midwifery was), and could never use obstetrical instruments with ‘advantage or precision’, even if presumptuous enough to try. Such remarks, together with allegations that midwives were generally abortionists, prompted one midwife supporter to remark that ‘the greatest slanders against the moral and intellectual characters of women have been uttered by practitioners of man-midwifery’.

This animosity towards midwives arose partly from men-midwives’ generally low status within the medical profession. Their specialty was not officially recognized as part of medicine and no official qualification existed in England to distinguish men with midwifery training from those with none. Hence men seeking such qualifications were forced to go to Scotland or the Continent. For decades leading accoucheurs had requested the English chartered medical corporations to establish such a qualification, but had been repeatedly rebuffed. Many leading medical figures viewed attendance on childbirth as ‘women’s work’, and below the dignity of professional men. In 1827 Sir Anthony Carlisle (later President of the Royal College of Surgeons) denounced man-midwifery as a ‘dishonorable vocation’, whose practitioners from financial motives sought to turn a natural process into a ‘surgical operation’. It was 1852 before the College established its Midwifery Licence and 1888 before such qualification was required for admission to the Medical Register kept by the General Medical Council, the doctors’ regulatory body established in 1859. Thenceforth midwifery was formally recognized in the UK as part of medicine.

Maternal mortality and the State

From 1839 maternal mortality statistics became available from the newly created Registrar-General’s Office for Births, Marriages and Deaths. The Office’s Statistical Superintendent, Dr W Farr, deplored the high loss of maternal life represented by the estimated rate for 1841 of nearly 6 maternal deaths per 1000 live births. Looking wistfully at Continental legislation for midwife regulation, Farr concluded that comparable arrangements at home were ruled out by British suspicion of State direction combined with general prudery concerning childbirth. Yet with better-instructed midwives, Farr declared, the annual 3000 maternal deaths could be reduced by a third. That some midwives were incompetent was demonstrated in press reports on those who had pulled out the womb or torn the child’s body from its head. Such disasters were paralleled, however, in accounts of ignorant male practitioners cutting out the womb or part of the intestines with scissors or knife. Some of these men (graphically described in the London Medical Gazette in 1845 as ‘disembowelling accoucheurs’) were regularly qualified medical men; others chemists, but in neither case was instruction in midwifery required by law.

The end of the midwife?

The midwife’s image had not been helped by Charles Dickens’ caricature in Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) of the unsavoury ‘Mrs Gamp’, a poor widow who, like so many over the centuries, earned her living by practising midwifery, sick and ‘monthly’ nursing, and laying out the dead. A blowsy, tippling, unscrupulous character, Mrs Gamp soon became the stereotypical midwife (see Fig. 2.4). But although along with Farr some medical men advocated the replacement of such midwives by respectable, trained women, certain accoucheurs, seeking a male monopoly of midwifery (achieved in North America by the 1950s), were pressing for the midwife’s total abolition. ‘All midwives are a mistake’, Tyler Smith told his students at the Hunterian Medical School in 1847, ‘and it should be the aim of every obstetric practitioner to discourage their employment’. Furthermore, because of its origin, the word ‘midwifery’ should no longer be used to describe male attendance on childbirth, being replaced by the new construct ‘obstetrics’. Here Smith well understood that a term of Latin origin, even if derived actually from the Latin for ‘midwife’ (‘obstetrix’), had a snob value which would further elevate men above their female competitors. This substitution of ‘obstetrics’ for ‘midwifery’ in male practice was, however, not fully achieved until after World War II.

The Royal Maternity Charity and maternal mortality

Directly in Smith’s line of fire was the 98-year-old Royal Maternity Charity. The Charity’s employment of midwives, however well instructed, Smith contended, was ‘degrading’ to ‘obstetrics’ and harmful to its clients, who instead should be attended by ‘educated’ practitioners. Yet the Charity’s statistics, published annually by the eminent medical men supervising its work, repeatedly disproved these allegations. Serving only poor women, many undernourished and living in unhealthy conditions, the Charity (and similar foundations) consistently demonstrated death rates of less than half the Registrar-General’s current rates for England and Wales.

A further onslaught on such charities came in 1870 from the obstetrician Matthews Duncan in his Mortality of Childbed. Dismissing the charities’ results as an impossibility since ‘educated accoucheurs’, in [affluent] private practice, lost five times as many women, Duncan postulated an ‘irreducible minimum’ of at least 8 per 1000, an admission, in fact, suggesting that the rich might indeed fare worse in childbirth than the poor.

Despite this obvious inference, the anti-midwife faction had an answer. The cause of higher mortality among wealthier women lay not with their medical attendants but with their own ‘artificial ‘ way of life, which disabled them for parturition. Increased (medical) vigilance was therefore necessary in attending them, not less. The degree to which childbirth among the prosperous was progressively viewed as pathology was evident in Chavasse’s 1842 Advice to a wife. While declaring childbirth a natural event, Chavasse required the ‘pregnant female’ to rest for 2 to 3 hours daily, while the post-parturient was to keep to a meagre diet, lying flat on her back for 10 to 14 days lest she should faint, haemorrhage, or suffer a prolapsed womb.

This invalidization of pregnancy and childbirth naturally implied more medical attention and higher fees, catching women in a double bind. Not only were they regarded as physically, intellectually and morally incapable of undertaking the ancient female duty of attendance on childbirth, but were also increasingly seen as requiring male assistance to give birth at all.

The midwives institute, midwife registration and maternal mortality

Accepting this reality, in 1880 three educated midwives, together with Louisa Hubbard, a wealthy pioneer in women’s employment, formed the Matrons Aid Society, later to become the Midwives Institute and ultimately the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) (Fig. 2.5).

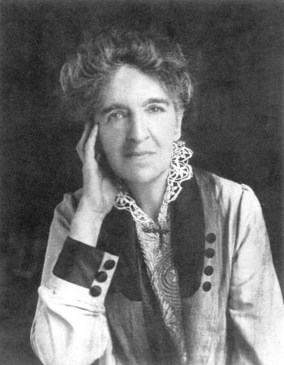

Figure 2.5 Rosalind Paget (1855–1948). Trained in nursing and midwifery, Miss Paget joined the Midwives Institute in 1886, in 1887 financing the establishment of the Institute’s journal, Nursing Notes. Also prominent in the Queen’s Nursing Institute, she was for 20 years its representative on the Central Midwives Board.

(Royal College of Midwives)

The Society’s avowed aim was the improvement of midwife practice, and, by implication, a reduction in maternal mortality. This was to be achieved through a registration Act similar to other professional legislation, as was the rehabilitation of midwifery as a respectable profession for educated women. Realizing that general practitioners might view registered midwives as competitors for their better-paying cases, the Institute argued that midwives would attend only women too poor to pay doctors’ fees and would not encroach on medical ground by acting in abnormal labour.

Yet what proportion of annual maternal mortality (still around 5 per 1000 live births) could be laid at the midwife’s door? The obstetrician Dr Aveling, when pressing for midwife registration before the 1892 Commons’ Select Committee, had implied that untrained midwives were responsible for most of the annual 3000 or so maternal deaths in England and Wales. Since there was as yet no notification of births, nor any system of identifying the birth attendant, this could only be guesswork. Indeed, WC Grigg, Physician to Queen Charlotte’s Hospital, concluded in 1891 that more cases of ‘injury and disaster’ resulted from the imprudent use of forceps and turning by doctors than from the negligence and ignorance of midwives.

The Midwives Act 1902

But how was a registration Act to be obtained? Despite continued strengthening of Continental midwife legislation, home governments, still heavily imbued with ‘laissez-faire’ ideology, declined to intervene. The Midwives Institute therefore began seeking friendly medical and Parliamentary support for the promotion of a Private Member’s Bill, a difficult task when women did not have the vote, there were no women MPs, and matters regarding childbirth were not discussed in polite circles. For 20 years, this handful of voteless women struggled against indifference and ridicule from an all-male Parliament and, latterly, bitter opposition from among general practitioners, their professional associations and the General Medical Council. Finally, however, possibly as a result of growing concern for the national welfare following revelations about the falling birthrate and poor health among Boer War volunteers, the first State registration measure in modern England for an all-female occupation became law. However, fierce medical opposition to registration had meant that the status of the new registered English midwife was much lower than that of her counterparts in leading Continental countries. Similar legislation for Scotland and Ireland (with the difference that new entrants must also be qualified nurses) followed in 1915 and 1918 respectively.

The Central Midwives Board

The Act established a midwives’ regulatory authority, the Central Midwives Board (CMB), with responsibility for keeping a ‘Roll’ of ‘certified’ midwives. In recognition of midwives’ general poverty, this regulatory machinery would be largely financed from public funds. Moreover, unlike doctors and chemists, midwives were not to be self-regulating. The Bill’s promoters, in order to keep their medical allies’ support, had been forced to concede that the Board should be in medical hands. The additional requirement of Local Government supervision through the agency of the (possibly hostile) Medical Officers of Health, meant that at both national and local level midwives would be regulated by a competing profession. There was a further burden: midwives, uniquely for a nationally regulated profession, were liable to erasure from the register (and subsequent loss of livelihood) for ‘misconduct’ in their private, as well as in their professional, life.

In 1905, the first year of enrolment, over 22,308 midwives registered. Of these, less than half held relevant certificates of competence, the remaining 12,521 registering as midwives in ‘bona fide’ practice. Five years’ grace was allowed for unregistered women to continue to practise, but after 1910 such activity became a criminal offence. For new entrants to the profession, 3 months’ approved training was required prior to taking the Board’s examination (doubled to 6 months in 1916 for non-nurse-trained applicants, in 1926 to 1 year, and in 1938 to 2 years). The Board’s rules limited midwives to attendance on natural labour (which included twin and breech deliveries), and required them to send for a doctor in difficult cases. Significantly, it forbade them to lay out the dead, traditionally an important part of poorer midwives’ work. Detailed directions also governed their daily practice, extending to their clothing, their equipment and their record-keeping; breaches of the rules could be punished by erasure from the Roll.

‘Certified Midwife’

Despite these restrictions on midwives’ independence, the Act worked gradually to raise the occupation’s status, consequently preventing the disappearance from the UK (as virtually happened in North America) of this ancient female calling. The requirement of hospital training and examination for new entrants, however, brought changes in the occupation’s social composition as younger, single women entered its ranks. Meanwhile, the poorer, older working-class women who had for centuries delivered their neighbours were prevented by the cost of training, books and examination fees from becoming registered midwives, being allowed to act as maternity nurses only (Leap & Hunter 1993:44–47).

As always, life could be very arduous for midwives attending women at home. This was especially so in the country, where long distances would be travelled in all weathers, on foot or by bicycle, possibly through difficult terrain. Fees were low (possibly 30 shillings to £2 per case) and generally paid in instalments during the pregnancy, though some payment might be in kind. In 1929, a few midwives with extensive practices were found to be earning over £275 annually, but many practising full time earned only £90–£100. Salaries for nursing association work in rural areas could also be low, the life very lonely and hardly supportable without private means. Hours worked could be very long, some midwives delivering 90–100 women a year. A Portsmouth midwife recalled how, when in independent practice, she once went without sleep for 4 days while single-handedly conducting seven deliveries, one of a  lb baby, finally going home to sleep the clock around twice (Leap & Hunter 1993:50–56,63–68).

lb baby, finally going home to sleep the clock around twice (Leap & Hunter 1993:50–56,63–68).

Domiciliary midwife practice appears to have followed guidelines laid down in contemporary obstetricians’ textbooks. Though allowed by the CMB to give mild analgesics (only doctors were allowed to give chloroform), some midwives employed warm baths and back-rubbing to ease pain. It was not until the 1940s that the self-operated Minnit inhalation analgesic apparatus became available in portable form for carriage on the midwife’s bicycle. In difficult cases midwives were required to send for medical help, but if this were delayed they would have to manage the emergency themselves, and if the doctor were inexperienced they might help him put on the forceps (ibid. 56–58,176–178). Midwife–doctor relations varied, but, as in earlier centuries, some doctors sought to blame midwives for their own incompetence (ibid. 56–58). After delivery, the mother was to lie flat for at least a day, staying in bed for 10 to 14 days for fear of uterine prolapse (ibid. 143,164–171,179). As tradition prescribed, she was kept, officially at least, on a meagre diet, a regimen that, as contemporary midwifery manuals show, only began to change in the 1950s.

The continuing problem of maternal mortality

When the 1902 Act was passed, it was expected that maternal mortality would fall as untrained midwives, known to be chary of sending for medical help in difficult cases, were gradually replaced by their formally trained successors. Instead, the rate remained puzzlingly stable. Worse still, from 1928 it had shown a significant rise, climbing to exceed 4 per 1000 live births in 1930. Interestingly, enquiries by the Ministry of Health showed that maternal mortality was lower among the poor, many of whom had poor health and lived in insanitary conditions, than among the better-off, who generally had medical attendance. Allegations of fatal abuse of instruments had followed male practitioners for over two centuries. Even now, reported an editorial in The Lancet (Anon 1929), many GPs confessed to routinely using instruments, solely to save time, maintaining that they could not afford to do otherwise. Another factor, contended Eardley Holland, President of the new College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, was the increasing tendency among GPs, despite warnings from leading obstetrics teachers, to view childbirth as pathology; consequently, they widened their indications for intervention, with catastrophic results (Holland 1935). Significantly, charitable and municipal outdoor midwife services for the poor consistently returned a maternal death rate of half the Registrar-General’s national figure, and lower than rates in more affluent areas where medical attendance predominated.

State midwifery

With continuing worries about the falling birth rate and high maternal mortality, Parliament’s response was the 1936 Midwives Act. This required County and County Borough Councils to provide for a whole-time midwife service adequate to local needs and free or at reduced cost to poorer women. Thenceforward, the majority of midwives would be salaried, uniformed, pensioned professionals, with time off and annual leave, offering a more complete service and receiving official recognition of their contribution to national wellbeing. Many of those not selected for the new service were bought out of their practices and those considered unfit compulsorily retired. Further, unregistered women were no longer permitted to act as maternity nurses. The Act passed without adverse comment from the medical press, probably because of general practitioners’ improved financial security (largely consequent on the 1911 National Insurance panel system), and GPs were now content to leave ‘cheap midwifery’ to the midwife. However, although municipal midwives were better off, broken nights followed by a full working day remained a feature of domiciliary practice (see Fig. 2.6).

The National Health Service, maternity care and the midwife

Twelve years later, in 1948, under the free and comprehensive National Health Service (NHS) established by the 1945 Labour Government as part of the new Welfare State, midwife, general practitioner and hospital services were provided free to all women, irrespective of income. A great expansion of professional education also took place and, at last, midwife training was free. Yet continuing prejudice was directed against non-nurse midwives. Indeed, the upper-middle-class ladies who had led the Midwives’ Institute to victory had come into midwifery from nursing, already made ‘respectable’ by Florence Nightingale and others. By being nurses first, they had cast a cloak of respectability over midwifery and established an ethos which was to prevail for over 80 years. Midwives lacking the sanitizing badge of a nurse qualification were treated as if carrying the lingering taint of ‘Mrs Gamp’, and although many such midwives had more midwifery experience than those holding nurse qualifications, midwifery promotion invariably went to the latter (Radford & Thompson 1988). Furthermore, the Scottish and Irish registration Acts had required all midwife pupils to be qualified nurses and over time English ‘direct-entry’ midwifery courses were officially discouraged, until by 1980 only one such school remained. Yet many nurses qualifying in midwifery never practised it, whereas the great majority of direct-entry midwives stayed in the work.

Place of birth

By the 1950s, the long-sought fall in maternal mortality had arrived. Sulphonamide drugs had appeared in 1936, followed a decade later by antibiotics. Together with stricter attention to asepsis and antisepsis in delivery and puerperium, these drugs had virtually eliminated puerperal sepsis, in 1930 still responsible for around 40% of maternal deaths. By 1945 the 1931–35 figure of 4 deaths per 1000 live births had been halved and by 1950 halved again. A crucial factor in this continued decline, however, as McKeown noted in relation to other health problems (McKeown 1976), has been the generally improved standard of living, resulting, in particular, in a dramatic reduction in rachitic pelves and anaemia (Worth 2002).

Despite these advances and the excellent results consistently achieved by domiciliary midwives, the trend to (more expensive) hospital delivery was officially encouraged, on obstetricians’ advice, as being safer for mother and baby in all cases, a view subsequently challenged by independent statistical analysis (Tew 1978). By 1958, 64% of births took place in hospital, many in general practitioner units (GPUs), smaller and more local than consultant-led units (CUs). With estimated maternal mortality rates (now more widely defined as deaths from causes attributed to pregnancy and childbirth per 1000 total live and stillbirths) as low as 0.18 for England and Wales in 1968 (DHSS 1975, Table 1.3) and 0.14 for 1969 in Scotland (Macfarlane et al 2000, II, Tables A 3.3.2, A 10.2.1), attention had turned increasingly to perinatal mortality. Defined as stillbirth and infant death within the first week, and standing at over 23 per 1000 births, this was higher in low-income groups (where maternal health was poorer) than among the better-off.

In 1970, the Health Department’s Maternity Advisory Committee, chaired by Sir John Peel, President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), presented its recommendations for remedial measures. These were based (unscientifically, in the absence of impartial statistical analysis) on the facile but erroneous equation between the falling perinatal mortality rate (PMR) and increasing hospitalization. Ignoring substantial general practitioner and midwife opinion to the contrary, the Committee recommended the transfer of home midwifery services to hospital control, effected in 1974 with their removal from elected local councils to the new unelected, hospital-dominated Area Health Authorities. Hospital delivery was now over 80% and, expecting this soon to reach 100%, the Committee pronounced ‘academic’ any discussion of their scheme’s advantages or disadvantages. The consultant-led ‘obstetric team’ (to include general practitioners and midwives) should therefore undertake the ‘education’ of the community on the ‘benefits’ of the reorganization.

Most obvious were the benefits to obstetricians’ status and career prospects, with increased resources directed to CUs at the expense of home midwifery and GPUs. Equally clear were the drawbacks for midwives and mothers. Midwives, who had successfully looked after women throughout pregnancy, labour and puerperium, enjoying independence and variety in their duties, and receiving recognition and respect in their localities, were forced into the impersonal hospital ward to work under the direction of the obstetrician, or restricted to community postnatal care. Women’s choice of place of delivery under the NHS was also disappearing. Many had preferred the familiarity of home, with the attention of a known midwife; others had chosen the local GPU, again with attendants known to them. Increasingly, however, they were to be compelled, possibly with children in tow, to make time-consuming visits to the large central district hospital for antenatal care, and to deliver in stark, impersonal surroundings among strangers. In many areas, women insisting on home birth or other non-interventionist care have since made private arrangements with a midwife or doctor at their own expense.

Pathways to abnormality: the ‘new obstetrics’

Perinatal mortality was considered further by the 1980 Commons’ Social Services Committee (the Short Committee). Despite hospital births now standing at 98%, and despite preferential allocation of medical resources to less favoured regions, the gap between perinatal mortality rates for wealthier areas, as compared with poorer areas, had widened. While admitting that some procedures employed in intrapartum care had never been scientifically evaluated, the Committee nevertheless accepted its medical advisers’ view that it was ‘reasonable’ to believe that ‘professional’ intervention could substantially lower the PMR. It therefore recommended further increases in consultant obstetrician posts with even greater concentration of births in large CUs and further restriction of home birth. Furthermore, wholly accepting the view of childbirth as pathology, its report demanded its routine management on a par with acute illness, in conditions of ‘intensive care’.

This was already the case in many CUs. Here, older obstetricians’ ‘watchful expectancy’ in normal birth had been superseded by the current North American doctrine of ‘active management’. With the synthesis in the late 1950s of oxytocin as ‘Syntocinon®’ had come a more reliable means of induction of labour. Hitherto, induction had generally been employed only in instances of fetal post-maturity and maternal pre-eclampsia; thenceforth, however, its use escalated, rising from 13% in 1958 to nearly 40% in 1974, and to 75% with particular consultants. Significantly, fewer births took place on weekends or Bank Holidays. Syntocinon® could also be used to accelerate labour already ongoing and to shorten it to conform to new restricted definitions of ‘normal labour’ derived from the arithmetical averages of the new ‘partograms’, rather than the limits of healthy experience.

Yet none of these procedures, observed critics, was wholly benign. Instead they led to a ‘cascade of interventions’ as obstetricians, many apparently still infected with the ancient Aristotelian notion of the female body as defective (Barnes 1984:1144) and hence requiring correction, persuaded themselves that techniques helpful in abnormal labour would assuredly benefit all cases. No birth therefore could be viewed as normal except in retrospect. Indeed, with multiple interventions, fewer births were truly normal. Syntocinon® infusions, together with continuous electronic fetal monitoring (which carries a high false positive rate and is associated with higher caesarean section rates), both inhibited mobility, for centuries valued as facilitating labour. Contractions were more violent and more painful than in natural labour, with greater danger of uterine rupture.

Enhanced pain required stronger pain relief, progressively supplied with new drugs and lumbar epidural analgesia. Epidurals diminish uterine activity, tending to hinder the natural rotation and descent of the fetus and inhibit the urge to push, thus prolonging labour, with the risk also of maternal circulatory collapse. More malpresentations and forceps deliveries resulted, with attendant risk to the child, and the discomfort of episiotomy, with possible lasting adverse sequelae for the mother (Wagner 2001). If the epidural were mismanaged, permanent paralysis, coma or even death could ensue (May 1994). Episiotomy became routine, mistakenly justified as preventing serious perineal tears and pelvic floor damage, and by 1980 being used on average in 52% of cases in England and Wales (Tew 1995:165). Dorsal delivery (the legs possibly raised in stirrups) replaced left lateral delivery, becoming the standard delivery position. Though it was known to be more painful for the woman and problematic for the fetus, it was praised in a leading midwives’ manual as more ‘comfortable,’ and as facilitating pushing (Myles 1981:309).

Moreover, as ‘failure to progress’ (defined by the strict timetables routinely now governing labour) increasingly resulted in caesarean section (CS), rates for this major operation rose rapidly. This fact alone led to further intervention – the prohibition or restriction of nutrition to every parturient to fit her for general anaesthesia in case a caesarean should be performed. Clearly such debilitating deprivation at a time when women need all their physical and mental strength – a deprivation now officially advised against but still imposed in some UK hospitals (NICE 2007:18) – is itself likely to contribute to ‘failure to progress’. Growing use of analgesic drugs, too, had consequences for the baby. Crossing the placenta, these have a depressing effect on the fetus, which may result in protracted difficulties in breathing and sucking, necessitating time in the (expensive) neonatal care unit.

Responses of the midwifery profession

Although the Peel and Short Committees had both recommended that full use should be made of midwives’ expertise, their recommendations pointed in the opposite direction. The disappearance of home midwifery and increased medicalization of hospital birth meant that midwives, officially excluded by the 1902 Act from attending abnormal labour, were now losing their role as guardians of normal birth. Midwifery skills were devalued in favour of interventionist methods that midwives themselves, many unwillingly, and against their professional judgement, were required to adopt (Reid 2002). Moreover, experienced midwives were increasingly required to defer to senior house officers who, despite their designation, were merely junior doctors doing their 6 months’ obstetric training. Further, hospital midwives’ work was increasingly compartmentalized into antenatal, intrapartum or postnatal care, some midwives seldom delivering a baby and practically none following a pregnancy through to labour and delivery.

For domiciliary midwives whose long years of low pay and broken nights had nonetheless given them the immense satisfaction of delivering women successfully in their own homes, the condemnation of home midwifery, despite excellent safety records, as ‘unsafe’ was tantamount to the negation of their life’s work. For many, the experience was traumatic and retirement could not come too soon (Allison 1996:ix–x). Others tolerated the transfer to hospital as bringing shorter, more convenient hours, less responsibility and improved career opportunities. Nor did the RCM seriously oppose this transformation of the midwife’s work. Overcome by the confidence with which obstetricians, generally male, and of superior educational and social status, put their case to Government, the College merely acquiesced as the ancient office of midwife was increasingly eroded, and its own avowed purpose, ‘the advancement of the art and science of midwifery’, effectively abandoned. Signalling its acceptance of the total hospitalization of birth in 1974, it abolished its long-standing Domiciliary Midwives Council. Some leading midwives expressed regret at these changes; others espoused them whole-heartedly, seeing reliance on technology as increasing midwives’ status, rather than, in fact, reducing it. Here was no sympathy for midwives seeking to undertake home delivery; and women desiring this, or intervention-free hospital care, were to be bullied into acceptance of what was now NHS policy.

Especially striking was the turnabout demonstrated in the 1975, 1981 and 1987 editions of Margaret Myles’ Textbook for Midwives, a standard work used in many midwifery schools since 1953. Hitherto, Myles, herself a midwife, had spoken of home as the ‘ideal’ place of delivery, affirming Nature’s power in the vast majority of cases to complete childbirth successfully unaided, and warning against the dangers of ‘meddlesome midwifery’. Yet these later editions dismissed the older philosophy of ‘watchful expectancy’ in labour as ‘negative’, applauding instead the ‘modern concept’ of ‘active management’, with its ‘planned positive approach’. The management of ‘normal’ labour now included routine interventions, justified as ensuring greater maternal and fetal safety, while psychophysical methods of pain management were dismissed in favour of drugs. Midwives must accept ‘modern ideas’, working to secure the compliance of the ‘misinformed’ minority of expectant mothers who demanded intervention-free birth and ‘outmoded’ continuity of carer. Hospital delivery was strongly advocated: indeed, for a midwife to take sole charge of a woman, depriving her of the ‘scientific expert care’ of the ‘obstetric team’, would be a retrograde step. Midwives should relish their new, more fulfilling role as technically qualified members of the medically controlled ‘team’ (as ‘mini-obstetricians’ is implied) rather than seeing themselves as clinically independent practitioners as sanctioned by the Midwives Acts. Not all midwives approved of these developments. Some, the Association of Radical Midwives, decided to fight the trend from within the NHS; others left the service in order to practise privately as independent practitioners, offering home delivery and choice of birth positions.

User protest and the ‘Active Childbirth’ Movement

Protests came, too, from among childbearing women themselves, their complaints supported by healthcare user organizations forming part of the post-war consumer movement. Among these were the National Childbirth Trust (NCT) and the increasingly assertive Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services (AIMS). AIMS demanded more sympathetic maternity care, including choice of home birth, of intervention-free care and of birthing positions, ideas generally dismissed in medical circles as the fads of a misguided middle-class minority. Such women, wrote one obstetrician, were too ignorant or selfish to accept their role as ‘patients’, even for their infants’ safety. Clearly viewing the womb as a railway engine, he censured complainants for ‘dictating their treatment’, thus relegating professionals ‘from the signal-box to the footplate’ (namely, from their rightful position of controlling labour to one of merely observing it). Moreover, despite radiological evidence that squatting enlarged the pelvic outlet by almost 30% compared with the generally used supine position (Russell 1982), upright delivery was condemned as too ‘primitive’ (outdated) or too ‘innovative’ (untested). Furthermore, the ‘bizarre’ positions ‘professionals’ would have to adopt would adversely affect their ‘sense of security’ in their work.

Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act, 1979

Meanwhile, midwives faced other problems following the implementation in 1983 of the Government-sponsored Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors Act, 1979. This replaced the different regulatory machinery for these three professions in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland with one umbrella organization, the United Kingdom Central Council (UKCC). Following representations to Government by a re-invigorated RCM, the midwife’s distinctive nature was recognized with the establishment of a statutory Standing Midwifery Committee to consider all ‘matters relating to midwifery’. However, since the Committee was subordinate to the nurse-dominated UKCC, midwives were no more a self-regulating profession than under the CMB.

Nurses’ lack of empathy for midwifery matters was especially manifest in Project 2000, the UKCC’s 1986 proposal for combining the basic education of the three professions in one 2-year nursing programme followed by a year’s specialization, with midwifery as one of the ‘specialties’. Midwifery education for students taking such courses would thus be reduced to 1 year. Opposing strongly, the RCM argued that midwives’ clinical responsibilities clearly distinguished them from nurses, and that to cut midwife education would demote midwifery to a branch of nursing (RCM 1986). Moreover, the proposal contravened the 1980 European Community requirements for UK midwives wishing to practise in EC countries, where midwives, as in former times, had longer midwifery training and generally were not nurses. Faced with this reality, the Council yielded. An interesting turnabout then took place. Direct-entry midwifery courses, instead of being phased out, were to be expanded and given higher status, thus reversing a century-old trend and preventing official downgrading of midwifery to obstetric nursing.

Finding a new voice

A further sign of a more vigorous, enterprising stance among midwives was the 1989 edition of Myles’ Textbook, now under new authorship. The new edition contrasted sharply with previous ones, with their authoritarian celebration of interventionist obstetrics. In an entirely new departure for a midwifery manual, it emphasized the midwife’s duty to accommodate, where feasible, women’s choice of labour and delivery positions, forms of pain relief and so on. Midwives should also strive to make this normal but critical life event as happy as possible for mother, partner and family. Another ‘first’ was the referencing of the text, along with suggested further reading, indications of a new vision among midwife educators, now holding up the ideal of the midwife as a life-long learner in a ‘research-based’ profession. Significantly, similar emphases characterized the corresponding edition of Mayes’ Midwifery, the other standard textbook in the field. Further noteworthy professional developments arising from the ranks were the foundation in 1986 of MIDIRS, a midwife-run quarterly critical digest of recent literature and research in maternity care. This, together with the arrival in 1993 of the British Journal of Midwifery, soon followed by other midwife-led publications, was to present a serious challenge to the staid Midwives’ Chronicle, official journal of the RCM, ultimately forcing it also to adopt a more proactive stance.

‘Choice in childbirth’

In 1991, on the initiative of Audrey Wise, MP, who wished to know why young women she knew were finding childbirth so traumatic, maternity services were again studied, this time by the Commons’ Health Committee (Chairman Nicholas Winterton, MP). Unlike previous enquiries appointed by the Health Department, the Committee did not start from the negative standpoint of childbirth as an inevitably hazardous enterprise needing medical management, but as a normal physiological function that healthy women could generally perform successfully unaided. For the first time, too, midwives were included among the advisers, and submissions, written and oral, invited from service users as well as providers. Again unlike previous Committees, Winterton placed more credence on impartial statistical analyses than on the unproven assertions of obstetricians.

Moreover, since evidence on safety did not support the policy of 100% consultant unit (CU) delivery, the Committee argued for wider choice of place of birth (House of Commons Health Committee 1992:xlviii). GP units, rural or urban, offered a compromise between home birth and delivery in a CU and their closure on presumptive grounds of safety or cost should be abandoned forthwith (ibid. lxv). Taking maternal satisfaction with maternity services as its criterion of success, the Committee condemned the current professional choice of the PMR as the sole yardstick of the performance of maternity services, arguing rather for these to be audited in terms of maternal morbidity (ibid. 1992:lxii).

Like other medical specialties, the Committee observed, obstetrics had been subject to fashion, procedures introduced merely because they were available, and used routinely without consideration of possible adverse maternal consequences (ibid. xlviii–xlix). Women should therefore be given the option of refusing interventions, including induction, electronic fetal monitoring, epidurals and episiotomies, rather than having to undergo them as routine (ibid. xxiii). They should also be enabled to feel in control of their labours, to adopt positions of choice (ibid. lxix) and to be attended throughout labour by the same midwife. The Committee summed up its philosophy under the tenets, ‘Choice, Continuity and Control’. Significantly, it concluded that essential to the development of the more user-friendly maternity services, was a re-assessment of the midwife’s role. Calling for the restoration of midwives’ former clinical responsibilities, the Committee condemned current use of midwives as ‘a scandalous waste of money’ (ibid. lxxxi).

The Government’s response, ‘Changing childbirth’ (DH 1993), accepted Winterton’s philosophy of ‘woman-centred’ care, suggesting 5-year targets towards the implementation of its recommendations. However, this document was merely consultative and lacked the ‘teeth’ necessary to enforce any widespread change. Women seeking home birth still reported GPs threatening to strike them off their NHS lists, while many Health Authorities refused them on grounds of midwife shortages. Where they existed, midwife-run units, despite their recorded low intervention rates and increased maternal satisfaction, remained on sufferance, Health Authorities resenting the expense of maintaining these ‘experiments’ in addition to their ordinary hospital establishment (Lee 2001).

Whose choice in childbirth?

Responding to ‘Changing childbirth’, the RCOG qualified its acceptance of the ideal of ‘woman-oriented care’, invoking considerations of ‘safety’, a veiled justification of current interventionist practice. Significantly, it also argued for ‘equal attention’ to be paid to the welfare of the fetus, ‘the other important person’ in the case (RCOG 1993). For centuries, English law had not recognized the unborn child as a ‘person’ (the principle underlying current abortion law). Yet in 1992, obstetricians from a London hospital had obtained a court order for a forced caesarean on a mother refusing her consent on religious grounds. Similar orders followed, all granted without maternal representation in court, until in May 1998 the Appeal Court ruled illegal the forcible invasion of a competent adult’s body, even if a woman’s life or that of her fetus depended on it. The fetus was not a separate person from its mother and its medical needs could not override her rights to self-determination. Notwithstanding this definitive judgement, many obstetricians persist in a curious doublethink. This allows them to view the aborted fetus (up to term if handicapped) as a non-person, but to describe the fetus of the pregnant mother who may resist intervention as a ‘patient’, thus, illogically and incorrectly, endowing it with full-person status with rights equal to, or overriding, those of the mother (RSM 2002).

Apart from the Appeal Court’s clear-cut confirmation of the parturient’s legal autonomy, how has user choice fared in general? For true choice to be exercised, full and unbiased information on available options is essential (see Ch. 34). However, a recent assessment of hospital antenatal information-giving showed that in some units choice was limited. In effect, women were steered towards acceptance of obstetrician-determined technological intervention through information that minimized its risks and exaggerated the potential harm of doing without (Stapleton et al 2002). Moreover, intervention was actually coming to be represented as part of normal birth. Indeed, a 2001 study in the Trent region demonstrated that in over 60% of the 956 deliveries recorded as ‘normal’ or ‘spontaneous’ (that is, excluding instrumental or CS deliveries), interventions had in fact occurred. These included amniotomy, induction, augmentation of labour, episiotomy and epidural anaesthesia. In about a third, induction or augmentation of labour had taken place, while 89% of amniotomies were performed before the cervix was fully dilated (Downe 2001, Downe et al 2001).

Childbirth a ‘surgical operation?’

Given this high level of intervention, it was unsurprising that the 2001 Scottish Expert Advisory Group reported that Scotland’s caesarean rate (CSR) approached 20%, while the National Sentinel Audit revealed even higher rates in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Moreover, remarkable variations in CSRs existed between regions and between hospitals. These disparities were inexplicable by reference to case-mix, as were variations in CS percentages ascribed to different primary indications, clearly demonstrating the absence of any agreed objective criteria of ‘need’. Disturbingly, while half the obstetricians responding to the enquiry considered existing rates too high, 21% did not. Furthermore, in private hospitals, where obstetricians are paid by item-of-service, much larger fees are paid for this invasive procedure than for the oversight of vaginal delivery. Here, the CSR has been much higher, in some over 40% (Churchill et al 2006:54). Yet the 1985 Consensus Conference of the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that no improvement in outcomes could be expected from a CSR exceeding 10–15%, a rate maintained by Holland and the Scandinavian countries, which have some of the world’s lowest maternal and perinatal mortality rates (Wagner 2000). Nor, declared Wagner, WHO’s former Director of Women’s and Children’s Health, was there any evidence for obstetricians’ claims that CS reduced perinatal mortality (ibid.).

Though the direct financial inducements that may influence obstetricians’ CS decisions in private hospitals do not apply in the NHS, the system of payment by results (PBR) has created perverse incentives for hospital trusts to favour elective CS (Baldwin et al 2007). Other factors include ‘daylight obstetrics’ to suit the obstetrician’s convenience (Brown 1996, Gans et al 2007), fear of litigation, and repeat CS (around 14% of the total [Churchill et al 2006:88]), thus further augmenting the CSR. Another element in the rise in CS is the 7% or so of cases recorded by obstetricians as responses to ‘maternal request’. Some women requesting CS are motivated by previous negative experience of vaginal birth; others are possessed by a general fear of childbirth generated by today’s culture, especially by TV (Baxter 2007, Gould 2007). Some have been persuaded that CS is safer for the baby (NICE 2004, Weaver & Statham 2005), an opinion the 2001 Sentinel Audit found was held by half of its obstetrician respondents. The Audit also found that obstetricians probably under-estimated how far women ‘choosing’ CS were in fact influenced by the advice they themselves had given. Obstetricians may also argue that they have no time to give women full and unbiased information on what is known about CS (Wagner 2000) and, as women’s testimony demonstrates, some obstetricians believe that women do not need this knowledge (Barbieri 2006).

Certainly, recent research suggests that a significant proportion of women who have had CS have not understood the reason for it (Baldwin et al 2007, Baxter 2007) and some complain that they have been brow-beaten into having caesareans they did not want (Weaver & Statham 2005). Indeed, AIMS reports that they are contacted almost daily by women desperate to avoid a caesarean (Beech 2006). Constituting 24% or so of all births for 2005/06, CS deliveries accounted for over 40% of delivery spending, at a cost of £2 billion a year to the NHS (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2006).

Governmental views

This financial burden on the NHS was duly noted in the 2004 CS guidelines from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), in the hope of reducing the ever-rising CSR (Scotland has similar guidelines). Risks to mother and infant of both methods of delivery were compared and CS discouraged where any supposed benefits over vaginal delivery were uncertain, while maternal request for CS was not automatically considered adequate grounds. Though many obstetricians regard the CSR as too high, others celebrate its increase, and the guidelines (’this edict’) came under immediate attack from two London obstetricians. Invoking the Winterton principle of ‘Choice in childbirth’, they declared CS the safest method of delivery for the mother and (especially) the baby, insisting that ‘most’ obstetricians shared this view (Fisk & Paterson Brown 2004).

Yet repeatedly the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has declared normal vaginal delivery to be safer both in the short and long term for both mother and child, and CS for non-medical reasons ethically unjustified (FIGO 1999, 2003, 2008). Significantly, also, in 2002 the leading private health insurance firm AXA-PPP ceased paying for CS because it was becoming increasingly difficult for them to distinguish between medically necessary sections and those that were a matter of personal choice (BBC 2002).

FIGO’s stance on the overall greater safety of vaginal over caesarean delivery is supported by the recent multicentre prospective cohort study (part of a WHO global survey) of 97,095 births. The study concluded that the increased CSR at an institutional level over recent years was not associated with any clear overall benefit for mother or baby, but linked with greater morbidity for both (Villar et al 2007).

Other negative effects may include emergency hysterectomy, reduced fertility, an increased rate of unexplained stillbirths, iatrogenic prematurity, fetal laceration, perforation of the maternal bowel and sepsis of the genital tract (Langdana et al 2001; Robinson 2004/5; Smith et al 1997, 2003a, 2003b; Wagner 2000). Indeed, two female London obstetricians propose that in the absence of medical indications CS should be performed only with a confirmatory second opinion (Bewley & Cockburn 2002).

‘Choice, Continuity and Control’?: Winterton revisited

Three years after the publication of its CS guidelines, NICE offered ‘best practice advice’ on the care of healthy labouring women and their babies (NICE 2007). Echoing Winterton, the guidelines stipulated that care should be ‘woman-and-baby centred’, women being treated with kindness and respect and given enough information to make their own informed decisions, including choice of birth at home (Fig. 2.7) or in a midwife-led unit. Mobility during labour should be encouraged to hasten the process, as it had traditionally been before the advent of the ‘new obstetrics’ in the 1970s, together with the adoption of birthing positions most comfortable to the individual parturient. Strikingly, supine or semi-supine delivery postures (part and parcel of the ‘new obstetrics’) were strongly discouraged as more uncomfortable and less conducive to the infant’s expulsion and, if all was progressing well, clinical interventions (such as amniotomy or oxytocin) should be neither offered nor advised.

How far, however, does this counsel of perfection square with current realities? Home births, currently averaging 2.5% of the total in England (less in Scotland, more in Wales), are actively discouraged by most obstetricians, general practitioners, and, indeed, midwives, whose general lack of experience of such birth leads them to fear it (Edwards 2005, 2008). Even where home birth has been agreed, it may not happen for lack of midwives. Moreover, midwife-led units provide for a mere 5% of total births. Significantly, despite their consistently good results (Rowbotham & Hunt 2006), government support for such centres is condemned by some obstetricians as a ‘cheese-paring’ move to substitute an ‘inferior’ service for that of the obstetrician-led CU (Carlisle 2007).

Women’s own views of their birth experiences were recently recorded by the Healthcare Commission’s (HCC) nationwide survey of 26,000 respondents giving birth early in 2007. Nearly a quarter of these women considered they had not been treated with kindness or respect, and around 30% that they had been excluded from decision-making during labour or delivery (HCC 2007). Only 61% had been able to choose their most comfortable position during the greater part of their labour, and despite the known links between continuous fetal monitoring and increased intervention (including CS) 45% of respondents suffered this (HCC 2008:41). Of those delivering vaginally, 12% exercised choice of birthing position, giving birth standing, squatting or kneeling. A quarter reported giving birth ‘sitting in bed’ (semi-supine), while as many as 57% delivered on their backs (supine), a position condemned by leading obstetricians 10 years ago (Steer & Flint 1999). Worse still, 27% of these delivered in the infamous ‘stranded beetle’ position with their feet in stirrups (HCC 2007). Continuous care by the same midwife throughout labour was enjoyed by only 20%, while 26% were left alone at a time of anxiety to them (ibid.).

Can we measure ‘risk’?

Underpinning the much-used obstetricians’ dictum that no birth is normal until it is over is the now ubiquitous concept of ‘risk’. That certain risks exist in pregnancy and childbirth has always been known, the most serious of which are generally readily recognizable by expert clinicians. Yet difficulties in ‘risk factor’ definition and quantification render risk-scoring ‘systems’ highly suspect, and their predictive values, positive and negative, have proved poor (Enkin et al 2000:49–51; Tew 1995:110–111,256–268,330–338).

Strait-jacket for labour: the partogram