Chapter 1 The global midwife

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Challenges in global midwifery for the 21st century

Midwives originating from the West will hold very different perspectives of childbirth and midwifery practice compared with colleagues from other countries, especially those classified as less and least developed (WHO 2007). Midwives worldwide aim to provide a safe environment for birth. However, countless women in today’s world are forced to experience childbirth, not as a fulfilling experience, but as one fraught with fear and danger. In the 21st century, a majority of women still cannot dissociate birth from death. Consequently, midwives are challenged to play a leading part in making childbirth safer. Of the 130 million babies born worldwide each year, it is estimated that almost 8 million die before their first birthday, 4 million in the first month of life (WHO 2006a).

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (see website) include efforts to improve the health of both women and children, particularly in the context of poverty and disease (Box 1.1). Making pregnancy safer challenges not only health professionals, but also technical experts, including water engineers, road builders, telecommunication experts and vehicle mechanics. Community mobilization even in the farthest reaches of the globe needs to find resonance in political will at the highest levels.

Contrasts and inequalities

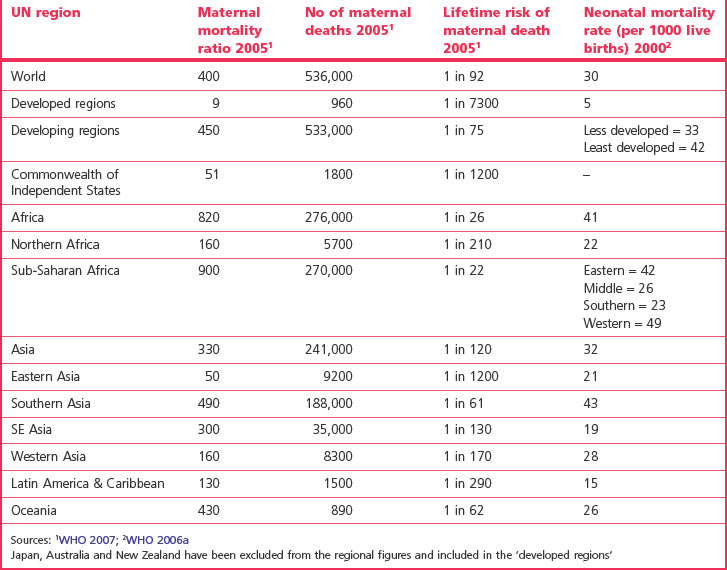

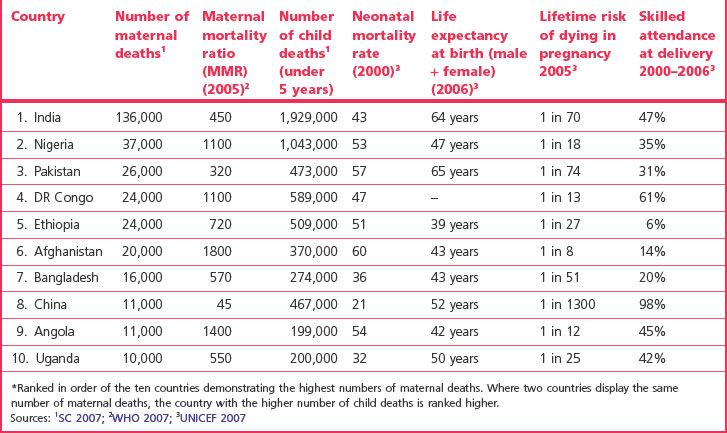

It has been stressed that one of the most striking measurable contrasts between industrialized and developing countries becomes evident in examining maternal mortality ratios. The 2005 estimates confirm the highest figures in sub-Saharan Africa followed by South Asia (Table 1.1). Globally, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) (see Ch. 16) reduction has proceeded on average by 1% between 1990 and 2005. MMR, as a key indicator for MDG 5 (Box 1.1), needs to decrease at a much faster rate if this goal is to be met (WHO 2007).

On a global scale, it is estimated that every minute of every day, a woman dies of pregnancy-related complications; the massive death toll exceeds half a million each year (WHO 2008a); 99% of these deaths occur in developing countries, figures varying considerably (Table 1.1). Motherless newborns are between 3 and 10 times more likely to die than those whose mothers survive (UNICEF 2008a).

Causes of maternal death

Main causes

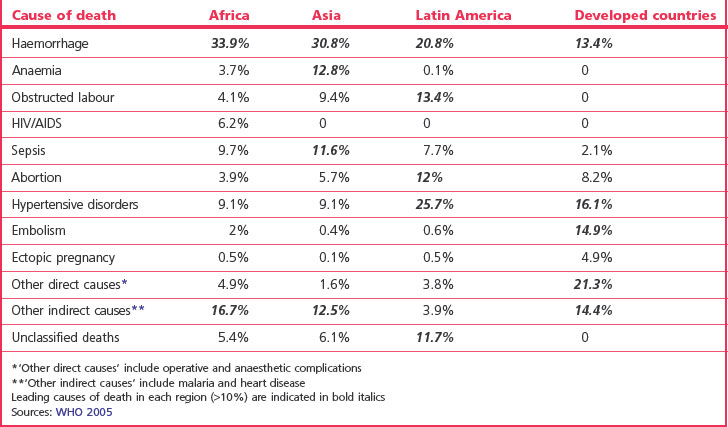

In developing countries, maternal death is the second most common cause of death after HIV/AIDS. There are five main obstetric causes of maternal death worldwide: haemorrhage, infection, unsafe abortion, hypertensive disorders and obstructed labour (WHO 2008a). Haemorrhage accounts for around a quarter of deaths globally. However, the leading cause of death tends to vary with the region (see Table 1.2). In many countries, adolescent mothers are twice as likely to die as other pregnant women (WHO 2008a) (see Ch. 16).

Predisposing factors

Maternal death is influenced by numerous factors. The reasons why women die have been described as ‘many layered’ (AbouZahr & Royston 1991). These layers include social, cultural and political factors that determine crucial issues including the status of women, women’s health and fertility, and their ‘health-seeking behaviour’. Failures in healthcare systems and transportation add to the problems.

One of the issues confronting an estimated 100–140 million women and girls each year is female genital mutilation (FGM) (see website and Ch. 58). The United Nations agencies are committed to addressing this practice which violates the human rights of a person (WHO 2008a).

Although sub-Saharan Africa accommodates just over 10% of the world population, 63% of all HIV infections are evident there (UNAIDS/WHO 2006). Linkage between HIV and maternal mortality has been established in the region (DFID 2005). Malaria kills more than a million each year and pregnant women and their unborn children are particularly vulnerable, placing them at risk for low birthweight and anaemia (UNICEF 2007). HIV is thought to increase the susceptibility of multigravid women to pregnancy-associated malaria (Keen et al 2007).

In addition to the 1500 women who die daily due to pregnancy-related causes, 10,000 newborn babies die, and it is estimated that most of these deaths could be prevented through skilled care during childbirth and the management of life-threatening complications (WHO 2008b). Whereas more than 99% of births are attended by skilled personnel in the most developed countries, this reduces to 59% and 34% respectively in the less and least developed countries (WHO 2007). It is estimated that mortality and morbidity in the perinatal and neonatal periods are caused mainly by preventable or treatable conditions (WHO 2006a). Infections, including pneumonia and neonatal tetanus, asphyxia, preterm birth and congenital anomalies contribute to 36% of the global deaths in children under 5 years (UNICEF 2007).

Maternal morbidity

Morbidity is less easily measurable. It is estimated that of the 136 million women who give birth each year, 20 million suffer pregnancy-related illness (WHO 2008a). The term ‘severe acute maternal morbidity’ (SAMM) has recently entered obstetric literature; several definitions include the concept of ‘near-miss’ and a situation where pregnancy-related complications lead to the failure of body organs. Utilizing the latter concept, it has been estimated that 4–8% of women in resource-poor areas will experience SAMM, compared with 1% in more developed areas (WHO 2005). Horrific injuries such as obstetric fistulae (see website), stigmatizing women in their families and communities, have been described as one of the most visible indicators of the massive gaps in maternal healthcare between the developing and developed world (WHO 2006b). Other morbidities include anaemia, infertility and depression.

Inequalities associated with being a mother

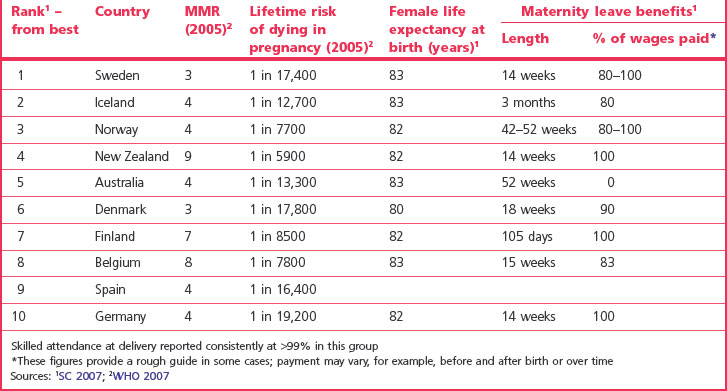

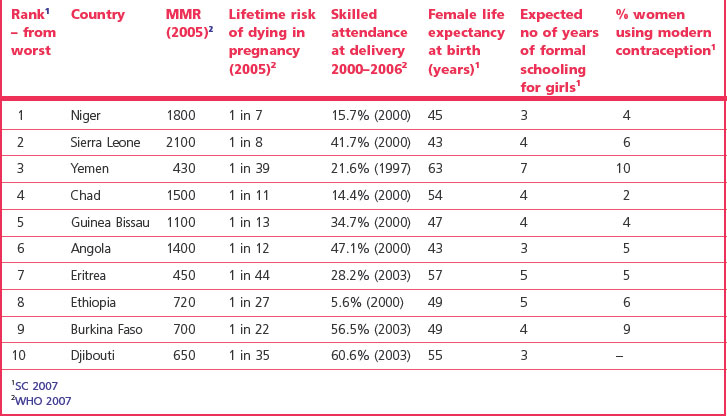

The experience of childbearing can be vastly different depending on the country of residence. Comparisons of data in Tables 1.3 and 1.4 provide insight into some of the major factors affecting women in the 21st century.

The highest numbers of women and children who die are evident in India, Nigeria and Pakistan, and the 10 countries listed in Table 1.5 contribute to the majority of global maternal and neonatal deaths.

Table 1.5 The top ten countries* with the highest numbers of maternal and child deaths (representing approximately 60% of the global MMR & NMR totals)

Survival of women at risk is extremely precarious in countries where health services are inaccessible, inadequate or non-existent. Risk is not eliminated in the West; vulnerable women still face enormous challenges to achieving safe childbirth wherever they struggle to exist.

The Safe Motherhood Initiative

It was estimated that 88–98% of all maternal deaths could ‘probably have been avoided’ (WHO 1986). Consequently, the Safe Motherhood Initiative was inaugurated in 1987 with the aim of reducing maternal mortality and morbidity by 50% by 2000 (SMI 1987).

Action messages agreed by Safe Motherhood Partners in 1997, setting priorities for the next decade (Box 1.2), find resonance today in the MDGs, including the current emphasis on safe motherhood and human rights. In order to work towards the MDGs (Box 1.1), many governments have committed to reducing poverty and promoting human rights when providing aid to the developing world (DFID 2006, Sveriges Riksdag 2005).

Reflective activity 1.1

Consider the Millennium Development Goals (Box 1.1).

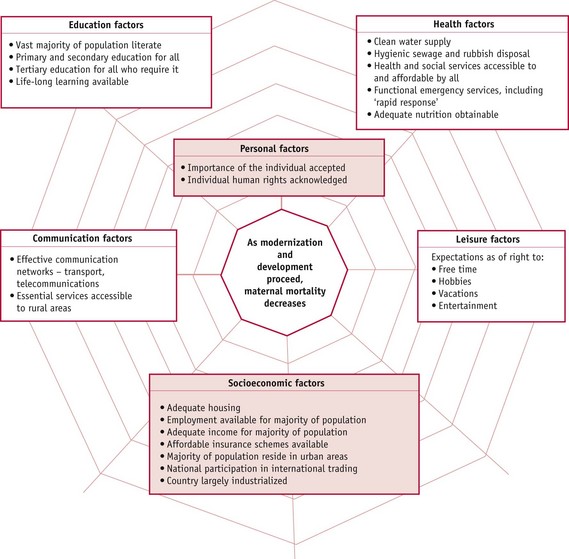

The impact of modernization and development

The process of modernization and development is inextricably linked with numerous health issues. Undoubtedly, as countries develop, childbirth becomes safer. This is a complex issue and the reader would do well to explore it further (Fig. 1.1). Progress of modernity tends to be inversely related to the lifetime risk of dying in childbirth. The website section entitled ‘The significance of historical issues’ offers explanations of how historical use of data has significance in understanding relationships between developments in maternity care and its practice influencing the safety of birth.

Ensuring skilled care during childbirth

During the second decade of the Safe Motherhood Initiative, focus moved towards a new era in promoting the concept of skilled care at every delivery. The term ‘skilled attendant’ refers exclusively to people with midwifery skills who have been ‘trained to proficiency’ in the necessary skills to enable them to ‘manage normal deliveries and diagnose, manage or refer complications’. These may be doctors, midwives or nurses but do not include traditional birth attendants (WHO 2000). The skilled attendant at delivery is regarded as a ‘reproductive health indicator’ (WHO 2006c) and as such is considered a proxy for a healthcare provider who can provide skilled care throughout pregnancy, labour and the postnatal period.

Political commitment has been historically and contemporarily associated with successful MMR reduction. Cuba, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand were amongst the countries that made earlier progress in reducing MMR and political commitment was critical to this (WHO 1998).

Epidemiological factors

If skilled attendance during childbirth were the only issue claiming association with significant MMR reduction, cause and effect, process and outcome may be easier to define and declare. However, socioeconomic and demographic indicators have been associated with safer childbirth internationally. These include female literacy rate, total fertility rate and urban population (see website for definitions).

Women living in rural areas are least likely to have access to skilled care, since the majority of the health services are habitually situated in urban areas. This issue is compounded by problems of transport and communication. Skilled attendants without access to essential equipment and a functional referral chain will be limited in their ability to save life, therefore the ‘enabling environment’ forms an essential component of promoting safer childbirth (WHO 2004, WHO 2008b). In countries with high MMRs there is often poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition and a low social status of women (Hafez 1998).

International organizations

International organizations may comprise governmental, intergovernmental or non-governmental organizations. There are also voluntary organizations, both religious and secular. Currently, there is an explosion of international aid sweeping into a volatile world economy, with an apparent movement of wealth from rich to poor nations. However, the reality is more complex. Issues surrounding aid and trade between governments and the role of such giant organizations as the World Bank have long raised ethical queries concerning who really benefits from some aid schemes (Juva 1994, Madeley et al 1994). The reader may find it instructive to consider the role of governments as well as international organizations in the context of poverty relief and debt repayment.

Without underestimating the valuable contribution of numerous others, some of the important organizations for international developments in maternity care are, for example:

Brief descriptions of each of these organizations are given on the website.

The place of the midwife in the global context

In the 21st century the world is increasingly described as a global village. Communications expedite both travel and news. Increased awareness should assist the global battle to combat the ever-present dangers and death associated with giving birth in the less developed areas of the world. Midwives, similar to other professionals, are likely to travel to other countries for study or work temporarily or permanently. The migration of workers from east to west has caused much heart searching in recent years. Migration rates of health workers trained in countries across Africa vary between 8% and 60% (Sambo 2007). There is an ethical dilemma associated with the ‘brain drain’ that saps poor countries struggling with massive health issues to supplement relative shortages in the wealthier western hemisphere.

Overall, Africa faces a shortage of 800,000 doctors and nurses and it is estimated that only 10–30% of the required skilled health workers are trained. It is from this situation that 20,000 skilled health professionals are lost each year through migration (Bruntland & Robinson 2008). Yet the right of individuals to improve their own career prospects and lift their families out of poverty is also an issue.

In order to identify situations in which the health-related MDGs, including MDG 5, are very unlikely to be achieved, WHO has indicated a workforce density threshold. Currently, 57 countries fall below this threshold and are classified as suffering a critical shortage of health workers. Thirty-six of these 57 countries are in Africa. This represents a global deficit of 2.4 million doctors, nurses and midwives. The greatest proportional shortfalls are reported in sub-Saharan Africa and enormous deficits related to population size exist in SE Asia (WHO 2006d). Not surprisingly, such statistics are commonly associated with countries reporting high maternal and child mortality figures (Tables 1.1, 1.4 and 1.5; see website).

Amongst the factors underlying the critical shortages in Africa, poverty and weak planning without appropriate motivation and retention schemes have been identified. In some countries, more physicians than midwives are being trained (Sambo 2007). It is estimated that between 2008 and 2015, another 330,000 midwives are required to achieve universal skilled care during childbirth (WHO 2008a).

To try to redress this crisis, international agreements have been formulated. These include a joint investment in research and information systems; agreements on ethical recruitment of, and working conditions for, migrant health workers; plus international planning of health workforces for humanitarian emergencies and global health threats. A commitment from donor countries to assist crisis countries in efforts to improve and support the health workforce has also been agreed (WHO 2006d).

Important considerations for midwives intending to work overseas

In the context of promoting safer childbirth worldwide (MDG 5), midwives may find that they are increasingly in demand for short-term or long-term assignments in countries struggling to address these critical issues. Some may also travel to more developed countries for study tours or personal professional advancement. Midwives practising in any country other than that in which they were educated must adapt to vastly differing situations.

Midwives who have been educated in an industrialized country intending to work in a less developed country need to have considerable experience and be conversant with relevant and current evidence-based practice. It can be helpful to learn some advanced clinical skills where practicable; for example, vacuum extraction, suturing cervical and vaginal tears, manual removal of placenta, neonatal intubation, inserting intrauterine contraceptive devices. Regulations may restrict midwives from acquiring some of these skills in the UK, but policy and tradition can sometimes be overcome in consultation with obstetricians and supervisors of midwives willing to arrange suitable learning opportunities. Short courses in tropical medicine and health can be most valuable. Discussions with persons experienced in the intended country of practice can be invaluable.

National authorities will specify their own country’s priorities in health. Increasingly, needs are expressed for midwives with expertise in education or management, but all midwives must be clinically skilled, able and willing to adapt to local needs. Ability to speak another language or a willingness to learn is an asset, and respect for different cultures and religions crucial. It is important for any expatriate workers to appreciate that they will never know, nor understand, many things in another country and that change must come from within a country. They must appreciate that ‘experts’ from another country can best help colleagues by demonstrating appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes with sensitivity. Midwives practising in cross-cultural situations need an acute sense of awareness, and an attitude of humility and willingness to learn. In a developing country, they need to be able to empathize with colleagues working in very different situations, exercise patience and cope using extremely limited resources.

Midwives who have been educated in less developed countries intending working or studying in industrialized countries will find more advanced technology in use than experienced at home. There may also be more emphasis on informed choice for women and partnership in care. They may be migrating to a society that is very litigation conscious and so will find that medico-legal issues impact upon midwifery and medical practice. Midwives therefore need a good understanding of current issues and popular demands, and may need to undertake an orientation programme. They must constantly update their knowledge and practice by critically evaluating research. There are benefits and hazards associated with both technology and freedom of choice demanding consideration. In returning to developing countries, indigenous midwives, as do expatriates, need to evaluate new practices in the light of local situations, available resources and national priorities, before attempting to transfer them from one country to another.

Midwives who have practised in countries where resources are scarce may be skilled at improvising and can sometimes share innovations with colleagues who face different, though significant, resource limitations. Midwives who have practised in regions remote from medical services can share with colleagues their experience of complications rarely seen in the West. It is salutary for all midwives to appreciate the consequences of delayed referral and intervention; the reality of, for example, obstructed labour and ruptured uterus, as inevitable consequences of cephalopelvic disproportion, and the frightening speed with which septicaemia can occur. Such complications will, of course, result in maternal death anywhere in the world unless there is appropriate and skilled intervention.

Issues relating to global midwifery have now become an essential component of the body of knowledge owned by midwives working in the West. In less developed countries, safer childbirth continues to receive increasing attention with the advent of the MDGs (Box 1.1). Safety is at the heart of every midwife’s practice, and whilst tragedies associated with childbirth are not observed on such a great scale in the West, experiences from the rest of the world can provide salutary lessons about fundamentals of midwifery care. Assertions that ‘that could never happen here’ must find evidence in reality. Safety needs to continue to be a priority in every country, including the UK. Historically, midwives have played a critical part and the concept of promoting maternal and neonatal health still falls naturally into the midwife’s domain. It is midwives who make their profession what it is today and what it will be tomorrow, globally. This warrants critical evaluation and constant reappraisal of essential professional issues, including midwifery curricula, standards of practice, protocol and policy, professional politics and practice ethics. These must reflect safety as a priority. Other issues, whilst important, will always be secondary.

During the first decade of the 21st century it has been recognized that ‘the main obstacle to progress towards better health for mothers is the lack of skilled care’ (WHO 2008a). Midwives represent a large part of the solution to this dilemma. The global midwife holds the key to a chance of life instead of death for the world’s childbearing women. Obstetric and paediatric colleagues form essential links in the life-saving chain that can bring hope to women, families and their communities in the most desperate need. The right to live is the most fundamental human right and midwives across the globe need to meet the challenge of the coming decades with superlative skills, infinite commitment and an enduring determination.