Chapter 30 The fetal skull

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

It is essential for a midwife to understand the parameters and characteristics of the fetal skull because of its significance during the mechanism of labour. Two key functions of the fetal skull are the protection of the brain, which is subjected to pressure as it descends through the birth canal during labour, and an ability to change shape, adapting to the process of labour in response to uterine contractions and the size and shape of the pelvis. By assessing the landmarks of the fetal skull, such as sutures and fontanelles, a midwife is able to diagnose the position and attitude of the fetal head in the pelvis and determine the most likely mechanism of labour and mode of delivery.

Development of the fetal skull

As the fetus develops in utero, the mesenchyme layer surrounding the brain starts to ossify, forming the various bones of the fetal skull. This process is called intramembranous ossification and begins between 4 to 8 weeks of gestation. The initial development of the skull occurs from this intramembranous structure, derived from neural crest cells and mesoderm. The intramembranous structure is divided into two major components, the neurocranium, which forms the protective case of the skull, and the viscerocranium, forming the bones of the face.

The neurocranium can be subdivided into the chondrocranium and the dermatocranium. The chondrocranium (cartilaginous part) is formed by the fusion of cartilages, and following ossification becomes the occipital, temporal, sphenoid and ethmoid bones. The dermatocranium (membranous part) is thought to arise from the external dermal scales developed to protect the brain. This lies under the superficial layers of the skin, covering and protecting the dorsal section of the brain, giving rise to the parietal and frontal bones.

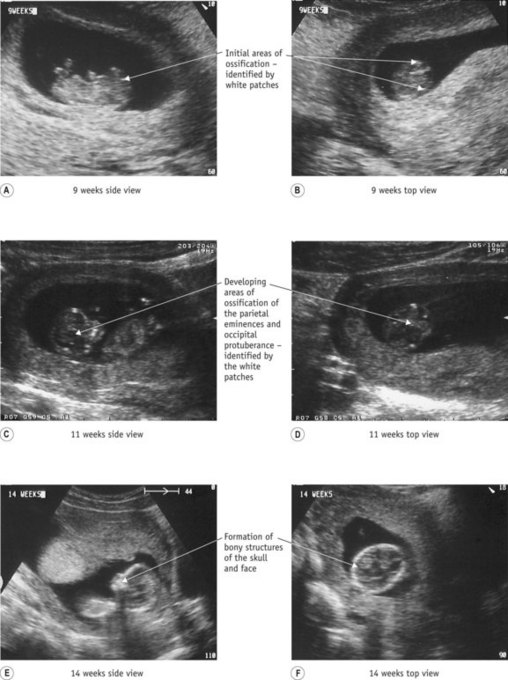

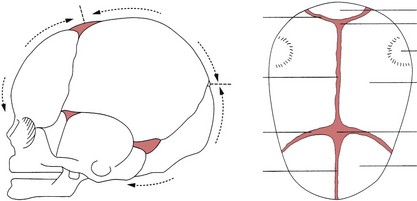

The earliest visible signs of development can be seen on ultrasonography at about 4 weeks’ gestation with calcification of the membranes and the development of the occiput. This becomes easier to determine from approximately 8 weeks, when intramembranous ossification is more prominent. At 12 weeks, the outline of the individual bones become evident (Moore & Persaud 2007, Sadler 2009) (see Fig. 30.1). Ossification of the bones continues throughout pregnancy with individual bones ossifying from their centre. At term, the bones of the skull are thin and pliable, enabling some movement of bones to take place during labour. The two frontal bones have usually united by term.

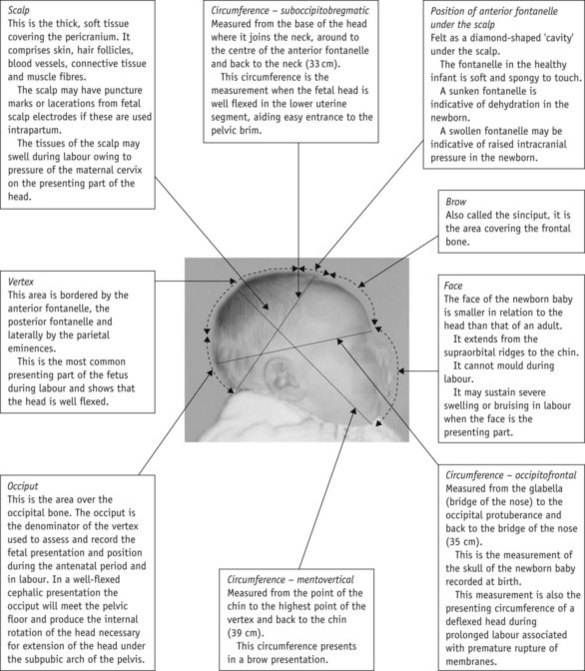

The external structures of the newborn skull (Fig. 30.2)

Following birth, the midwife examines the external structures of the newborn head in order to identify any unusual characteristics or abnormalities in the skull structure. A baseline measurement of the newborn skull is sometimes taken during this procedure and documented within the child’s neonatal records.

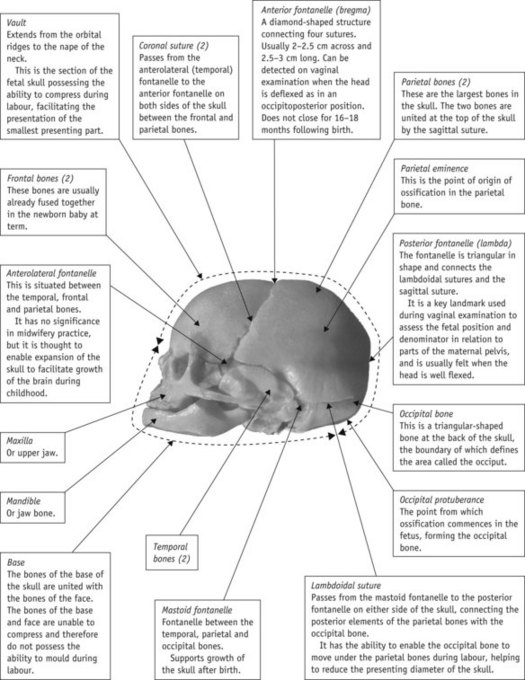

The skull (Fig. 30.3)

The fetal skull is a complex structure consisting of 29 irregular flat bones with 22 of these paired symmetrically: 8 bones form the cranium, 14 the face, and 7 the base. Knowledge of the fetal skull in the antenatal period enables a midwife to assess the size of the fetal head in relation to the size of the pelvis, assess engagement of the fetal skull in the pelvis (Dietz & Lanzarone 2005). It also helps inform reviews of ultrasonography and pelvimetry reports.

Sutures

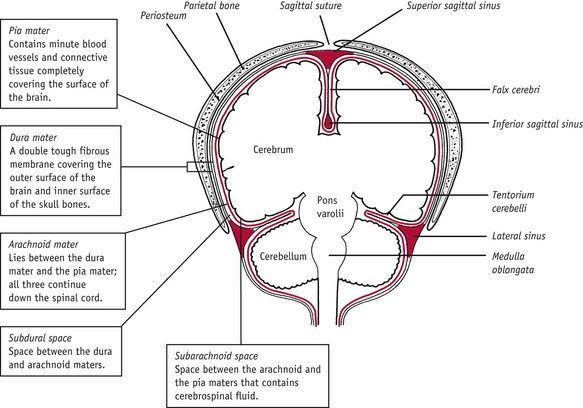

The sutures of the fetal skull are soft fibrous tissues linking some bones of the skull. They enable moulding of the head to take place during labour and expansion of the brain as it develops during childhood.

Fontanelles

A fontanelle is a membranous, non-ossified area of the skull where three or more sutures meet.

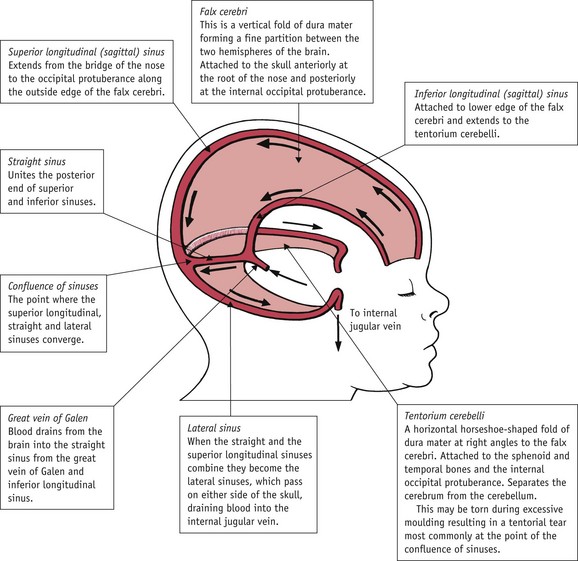

Sinuses

A sinus is a naturally occurring cavity in the body. Sinuses enable blood to circulate throughout the skull and into the brain membranes. The sinuses associated with the frontal, ethmoidal, sphenoidal and maxillary bones change shape during puberty and are thought to be associated with voice tone.

Reflective activity 30.1

Use the diagrams of the fetal skull in Figure 30.19 to revise the information outlined within this chapter. Photocopy the diagrams and revise the structures until you are confident that you know all of the components of the fetal skull and their application to midwifery practice.

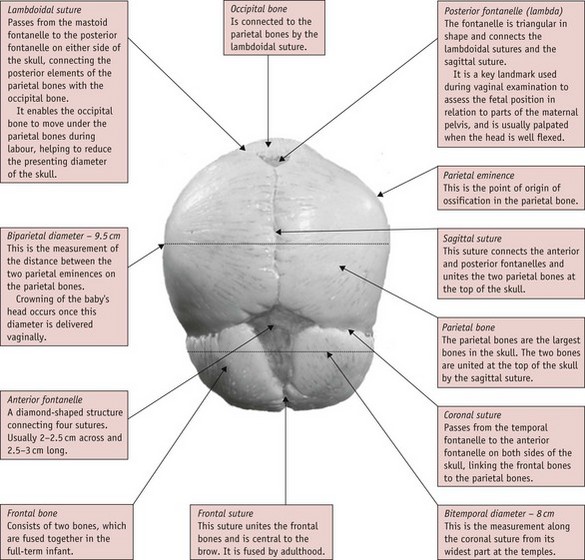

The bones and regions of the skull (Figs 30.3 and 30.4)

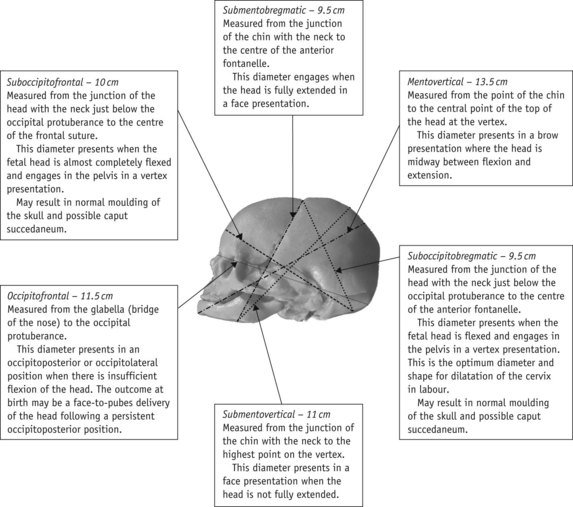

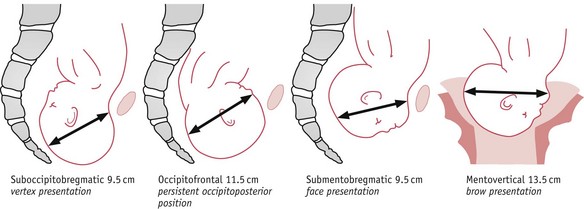

Measurements of the fetal skull

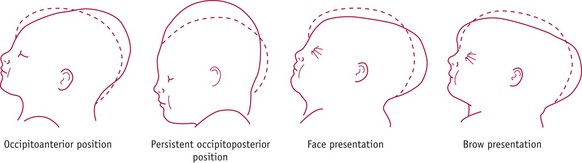

The presentation and position of the fetal head in relation to the pelvic brim, influence the degree of flexion or extension of the head and determine the precise realignment of the skull bones during labour and delivery. To assess the skull size in relation to various diameters of the maternal pelvis, diameters of the fetal skull have been measured to correspond with common postures adopted by the fetal head as it enters the pelvic brim (Figs 30.5 and 30.6). Each of these diameters and degree of flexion and extension of the fetal head has a direct impact on the progress and possible outcome of labour. By understanding this, the midwife can suitably inform the mother so that decisions can be made on positions in labour, pain relief and subsequent care of the baby at delivery. It is important to remember, though, that these measurements are only an estimate and vary considerably depending on the baby’s size and weight.

Reflective activity 30.2

When you next examine a baby, pay particular attention to the skull bones, sutures and fontanelles, which can easily be felt under the scalp. Note the degree of tension of the anterior fontanelle to assess the well being of the newborn. Familiarize yourself with the importance of these structures within midwifery practice.

Internal structures of the fetal skull

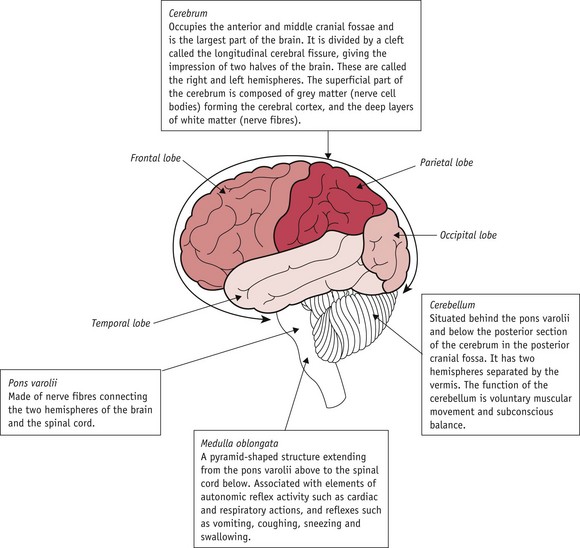

The anatomy of the brain

The internal structures of the fetal skull, although protected by the cranium, are at risk because of the skull’s ability to change shape during labour and birth. Altering the shape of the skull can result in overstretching of the internal structures and tearing of tissues or rupture of blood vessels.

Regions of the cerebrum (Fig. 30.7)

The regions of the cerebrum are divided according to the bones under which they lie:

Moulding of the fetal skull during labour

The fetal skull has a unique ability to flex during birth, while adapting to prolonged compression, to enhance its passage through the birth canal. This adaptation process is termed moulding, a process during which bones of the skull override each other as a result of pelvic girdle pressure (Fig. 30.10).

Moulding can increase or reduce the diameters of the skull by up to 1.5 cm. In normal moulding, the frontal bones move under the anterior aspects of the parietal bones, with the occiput moving under the parietal bones at the rear. This enables the skull to change shape but not volume. Where one diameter is decreased, another will be increased to accommodate the volume (see Table 30.1 and Figs 30.11 and 30.12). Where there is extreme or rapid moulding or abnormal compression of the fetal skull, a tear in the falx cerebri or tentorium cerebelli can occur.

Table 30.1 Variations in the diameters of the fetal skull due to compression and moulding

| Presentation | Effect on diameter |

|---|---|

| Vertex presentation with good flexion | |

| Persistent occipitoposterior position of the vertex (POP) | |

| Face presentation | |

| Brow presentation |

The midwife must record the degree of moulding present at birth. During the neonatal examination, the midwife reassesses moulding to ensure it is decreasing, and this may include taking measurements of the occipitofrontal circumference. Posterior moulding reduces within a few hours of birth, whereas anterior moulding is visible longer, decreasing over the first 48 hours of life.

Injuries to the fetal skull and surrounding tissues

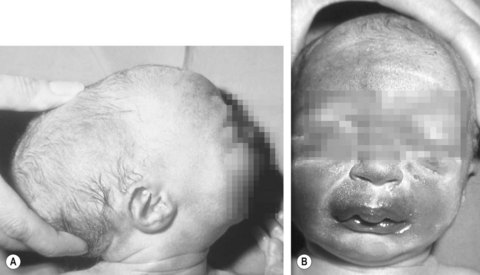

Caput succedaneum

A caput succedaneum is an oedematous swelling within the superficial connective tissue layer of the scalp (see Figs 30.13 and 30.14). The swelling results from the pressure exerted on the fetal head by the cervix during labour. Oedema collects in the unsupported section of the fetal head, which protrudes through the opening developed by the dilating cervix. The size of the swelling depends on the stage of cervical dilatation, and at full dilatation it may cover an extensive section of the presenting part. Not all babies develop caput, as factors such as duration of labour, strength of contractions and descent of the presenting part, all influence its development.

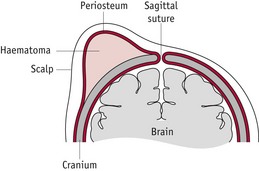

Cephalhaematoma

A cephalhaematoma is bleeding between the periosteum and the bone of the fetal skull (Figs 30.15 and 30.16). It is caused by friction of the skull against the pelvis or forceps during labour, and is associated with asynclitism of the fetal skull (the sideways rocking mechanism of the fetal head as it descends), or trauma following a vacuum extraction. Injury to the fetal skull results in the periosteum separating from the underlying bone with subsequent bleeding between layers. The resulting swelling is confined to the area of the affected skull bone by the periosteum layer. A cephalhaematoma can be present in more than one bone but occurrs most commonly in the parietal bones. The affected area is initially soft, but as osmosis occurs, fluid is removed and the area becomes firm.

Characteristics of cephalhaematoma

Treatment for this condition is rare, as most cephalhaematomas disperse naturally. The neonate is usually unperturbed by the injury or slightly irritable and requiring gentle handling. As with any blood loss, the baby must be monitored for signs of anaemia and jaundice as lysis of blood occurs, and vitamin K is administered to increase prothrombin levels and assist with clotting.

Lacerations

Lacerations to the scalp or face can result from fetal scalp electrodes, fetal blood monitoring or instrumental delivery. They usually require little or no treatment and heal quickly. The aim of neonatal care in this instance involves prevention and detection of infection and promotion of wound healing.

Chignon

A chignon may result following application of a vacuum extraction cup to the fetal scalp during delivery (Fig. 30.17). The vacuum cup is applied to the scalp and suction applied, drawing the scalp into the cup. Any slight movement of the scalp layers results in the area under the cup becoming oedematous and bruised. The result is an oedematous structure the same size and shape as the vacuum cup. This condition usually disappears within a week following delivery. In rare cases, vacuum extraction has been associated with subaponeurotic haemorrhage, when bleeding occurs below the epicranial aponeurosis. Bleeding in this instance may be extensive and so admission to a neonatal unit for observation and treatment is necessary.

Internal injuries

Tentorial tear

The tentorium cerebelli is a fold of dura mater within which are present the venous sinuses containing blood being removed from the brain. On rare occasions, the fetal head can be compromised by a difficult delivery or excessive or abnormal moulding, resulting in tearing of the membranes followed by cerebral bleeding (Fig. 30.18). This damage is often labelled as a tentorial tear.

The baby presents with signs of cerebral irritation and raised intracranial pressure, including a tense, expanded anterior fontanelle, asphyxia (bradycardia and apnoea), and convulsions. In these instances, the midwife must seek medical aid and arrange transfer to a neonatal intensive care unit for observation (see Ch. 48).

Reflective activity 30.3

Revise the internal structures of the fetal skull.

Visit your local neonatal intensive care unit to discuss the current treatment and care required by a baby with a tentorial tear.

Make notes on the advice given, including signs and symptoms to enable you to detect this condition and current patterns of care available for this baby.

The relevance of the fetal skull to parents

It is important midwives share their knowledge with parents in order to expand understanding of the needs of their baby. This commences in the antenatal period when the midwife discusses the nutritional needs of the fetus during development and growth, and explains the link between the mother’s pelvis and the fetal skull during labour.

Immediately following delivery, during examination of the neonate, the midwife can point out to parents the key features of the skull and their significance, to include fontanelles and sutures, and the presence of any deviations from normal, for example a caput.

During the postnatal period, it is important that the midwife discusses checking the anterior fontanelle as a measure of the neonate’s wellbeing. Box 30.1 provides a useful checklist for the midwife to use in educating mothers and others in the care of the baby.

Box 30.1

Helpful information points for parents

Conclusion

Knowledge of the anatomy of the brain and fetal skull enables practitioners to understand the role they play during labour and birth, helping them to assess, prevent, predict and diagnose potential and actual morbidity, while understanding the process of natural changes within the skull that help facilitate the birth of a baby.

Following birth, the midwife uses skills of observation and diagnosis to ensure the baby’s health and wellbeing. Knowledge of the structures outlined in this chapter enable the midwife to provide health promotion information and advice to parents, on both the process and outcome of birth, and the subsequent care their new baby requires.