Chapter 48 Congenital anomalies, fetal and neonatal surgery, and pain

Introduction

Congenital anomalies are defects/abnormalities present at birth, occuring in approximately 2–3% of babies (Boyd et al 2005, ONS 2010). Congenital abnormality is distinguished as:

Congenital anomalies can affect any part of the body; and can be major, for example a congenital heart defect such as Fallot’s tetralogy, through to minor, such as an extra digit or tongue tie. Minor anomalies are usually only registered if they are associated with other major malformations or syndromes (EUROCAT 2009). The focus of this chapter is the registered anomalies and syndromes; for more minor anomalies, see website.

Registration of anomalies and syndromes

Ever since rubella and thalidomide were discovered as powerful teratogens, various worldwide registries have been set up to facilitate research and surveillance concerning environmental causes of congenital anomalies (Misra et al 2006). These include:

Antenatal anomaly screening

Ultrasound scan screening for fetal anomalies has been fully integrated into antenatal care, but ultrasound scans have their limitations and hold no guarantee that all anomalies may be identified (see Ch. 33); in a small number of cases, babies are born with abnormalities. It is vital that midwives take a detailed medical, family and obstetric history at antenatal booking in order to identify risk factors for specific diseases and facilitate genetic counselling and appropriate investigations.

It is also essential the midwife carries out a thorough initial examination of the newborn at birth because some anomalies need to be investigated and dealt with immediately (see Ch. 41).

Antenatal screening enables greater parental choice as ultrasound scanning can identify:

Midwives should ensure that women get the opportunity to discuss fully the risk factors, possible results, implications, prognosis and management options for any condition with the appropriate health professional prior to further screening to ensure informed consent is given (NICE 2008, UKNSC 2007).

Aetiology

Whilst the cause of many congenital anomalies remains unknown, there are some known factors:

Genetic factors

Each human cell has a total of 46 chromosomes arranged in 23 pairs, one of the pair from each parent (see Ch. 26). Every chromosome carries a unique blueprint of its parent’s characteristics in the form of genes. There are two sex chromosomes (X from the mother and either X or Y from the father); the remainder are called autosomes.

Genes may be dominant or recessive:

The incidence of complex abnormalities is also increased with certain maternal diseases, such as unstable diabetes (Farrell et al 2002) and phenylketonuria.

Teratogenic factors

Examples of well-documented teratogens are:

Central nervous system anomalies

Spina bifida

Spina bifida is the commonest neural tube defect. Improved antenatal detection, therapeutic termination and routine vitamin supplementation (taking folic acid daily prior to conception and during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy) have accounted for a dramatic drop in the incidence.

There are three main types of spina bifida:

Anencephaly

The vault of the skull is absent with almost no development of the exposed brain. The baby has large protruding eyes and wide shoulders, the face presents during labour and polyhydramnios is found in about 50% of cases. Second trimester screening for abnormally elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein and low oestriol concentration, has been cited as highly predictive of lethal defects, particularly anencephaly (Benn et al 2000). This condition is incompatible with life and many parents may opt for termination of pregnancy. Parents who decide to continue with the pregnancy need ongoing support, especially during labour and birth.

Whether or not parents see the baby at birth is a matter for them to decide but it has been recognized that this may assist with the grieving process and helps in understanding the nature of the abnormality; also, in reality, the baby may not look as the parents imagined (see Ch. 70). The baby should be carefully wrapped before showing the infant to the parents and the midwife should establish whether the mother wishes to hold the baby rather than just look. Not all women will initially want to hold the baby but may want to do so later and this should be accommodated. If the baby is born alive, he or she will be nursed in the Special Care Baby Unit. These babies usually do not survive more than a few days.

Hydrocephalus

An excess of cerebrospinal fluid, caused by an obstruction or overproduction, distends the ventricles of the brain. Antenatal diagnosis is usually by ultrasound scan. The head circumference of a hydrocephalic baby is at least 2 cm larger than the 90th centile for gestational age, cranial bones are soft, fontanelles large and the sutures wide. This highlights the importance of accurate measurements at birth, which should be plotted on the appropriate centile chart.

Perinatal surgery, with the insertion of a shunt to drain fluid from the lateral ventricle into the peritoneal cavity, has proved a successful palliative treatment in more severe cases.

Microcephaly

Microcephaly is defined as a very small vault to the skull, and may be either:

These babies are usually mentally impaired and there is a high association with other abnormalities.

Abnormalities of the respiratory system

Diaphragmatic hernia

This condition develops as the result of a defect in the formation of the diaphragm, usually on the left side. The bowel and abdominal viscera herniate through the diaphragm and continue to develop in the thoracic cavity. These organs compress the developing lung and can result in pulmonary hypoplasia (Jesudason et al 2000).

This abnormality may be identified by early ultrasound scanning. Prenatal counselling should prepare parents for high mortality and morbidity rates – only approximately 50% of affected babies survive. Open fetal surgery has been carried out for this condition but carries significant risk to both mother and fetus; the development of fetoscopic surgery has improved outcomes and is considered to be the way forward (Nelson et al 2006).

Postnatal surgery involves replacing the bowel, stomach and any other herniated viscera into the abdominal cavity and repairing the diaphragmatic defect. Postoperative care centres on maintaining adequate oxygenation and respiratory support while pulmonary growth occurs.

Choanal atresia

In this condition, the posterior nasopharynx is blocked, unilaterally or bilaterally, by a membranous or bony septum, causing acute respiratory problems from birth, as neonates breathe mainly through their nose. Dyspnoea and cyanosis relieved by crying are classic symptoms, since only in this circumstance can the baby inspire adequately. Diagnosis is confirmed by being unable to pass a nasal catheter, and immediate treatment is the insertion of an oral airway. Surgical correction is necessary.

Abnormalities of the alimentary system

Cleft lip and cleft palate

Cleft lip, with or without a cleft palate, may be unilateral or bilateral and can involve the soft palate, hard palate, or both. This is one of the most common structural birth defects, with an incidence of 1 : 700 – the incidence of cleft palate alone is 1 : 2000 births. Cleft lip is usually diagnosed on ultrasound, but cleft palate may not be; the palate should always be carefully checked during the midwife’s initial examination of the neonate, as a slight deformity can easily be missed.

The cause of cleft lip and/or palate remains largely unknown. The majority are believed to have a multifactorial aetiology including genetic and environmental factors. Cleft lip and palate is also associated with other syndromes, including trisomy 13 and 18 and fetal alcohol syndrome (Hodgkinson et al 2005). There is often a family history of such abnormalities, and prenatal genetic counselling should be offered in such cases.

A cleft lip can look disfiguring, but the midwife can reassure parents that these can now be repaired extremely skilfully. Feeding problems frequently occur, often related to the baby being unable to form a seal around the nipple or teat. Breastfeeding is not impossible and should be encouraged and assisted wherever possible, with referral to a lactation specialist (see Ch. 43).

In the past, because of concern about speech function, repair would be undertaken during the neonatal period; it is now recommended that lip repair takes place at 3 months and palate repair at 8 months of age (Hodgkinson 2005).

The outcome for these babies and support for parents has improved considerably since the implementation of multidisciplinary care because many of these infants may have hearing problems and/or require ongoing speech and language therapy for many years.

Pierre Robin syndrome

A midline cleft of the soft palate, without a cleft lip, micrognathia (small mandible) and abnormal tongue musculature (glossoptosis) are the main features of this syndrome. Until the defect is repaired, the baby must be nursed in the prone position to prevent the tongue protruding through the cleft and obstructing the airway. In severe cases, a nasal airway or dental prosthesis is kept in situ until surgical repair. There is a high incidence of aspiration pneumonia and feeding difficulties, but if the baby survives the neonatal period, the prognosis is good.

Oesophageal atresia (OA) and tracheo-oesophageal fistula (TOF)

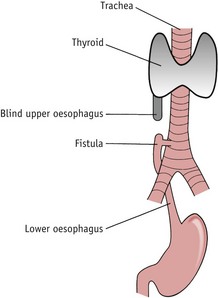

OA affects about 1 : 4000 neonates. In this malformation there is a blind ending to the upper end of the oesophagus, usually at the level of the third or fourth vertebra (see Fig. 48.1). Ninety per cent of babies will also have an oesophageal fistula, where there is a connection between one or both portions of the oesophagus and the trachea. Associated anomalies are present in 50% of cases.

Polyhydramnios should always alert the midwife to the possibility of OA/TOF, as the fetus is unable to swallow amniotic fluid, leading to its accumulation. In all cases of polyhydramnios, the midwife should pass a 10-FG nasogastric tube to assess the patency of the oesophagus before oral feeds are given. OA can sometimes be detected using ultrasound, and if this is the case, the baby should be born in a specialist unit with facilities for paediatric surgery.

OA should also be suspected at birth if copious, frothy oral secretions are present. If a fistula is present, aspiration will cause cyanotic episodes. In these circumstances, the midwife will immediately refer the infant to a paediatrican.

A 10-FG nasogatric tube will be passed to assess patency of the oesophagus. The tube should not be too soft (or small) as it may curl in the back of the throat or in the blind pouch, whilst appearing to reach the stomach. An X-ray may be taken to confirm the tube has reached the stomach. Surgery involves anastomosis of the ends of the oesophagus and division of any fistula. If the gap between the oesophageal ends is too wide, a portion of the colon or jejunum may be grafted on. Gastrostomy feeds will be necessary until repair is complete.

Duodenal atresia

The incidence of duodenal atresia is 1 : 6000 – in one-third of cases, associated with trisomy 21. The patency of the duodenum is interrupted; projectile, bile-stained vomiting occurs within 24 hours of feeds being commenced. An abdominal X-ray shows a classic ‘double bubble’ appearance. Surgical correction is required.

Imperforate anus

The incidence of imperforate anus is approximately 1–3 per 5000 births. There is a high association with other anomalies, with genitourinary abnormalities present in almost half of cases.

As part of the midwife’s initial neonatal examination, the anus must be visually examined for signs of patency (see Ch. 41). No objects should be inserted, but urgent paediatric referral made if there is any doubt. It is important that the midwife notes when meconium is first passed, and referral for further investigation should be made if this does not occur within 24–36 hours. Meconium-stained liquor is not indicative of a patent anus, as a fistula may be present. In the absence of a fistula, the baby will fail to pass meconium, and will have abdominal distension and bile-stained vomiting. Surgical repair involves the formation of a temporary colostomy, which can be very distressing for parents.

Hirschsprung’s disease (aganglionosis)

This is an absence of ganglion cells in the nerve supply that controls peristalsis in the rectum and distal colon. It is an inherited disorder, involving several different genes (Martucciello et al 2000). The incidence is 1 : 5000 neonates, and four times more common in male infants.

Features include delayed passage of meconium, subsequent infrequent, offensive stools, abdominal distension and vomiting. Any baby who has not passed meconium within 24–36 hours must be referred to a paediatrician for further investigations.

A temporary colostomy may be required prior to surgery to remove the aganglionic segments of bowel. Despite apparently successful surgery, the long-term outcome may be poor for some children who can suffer severe constipation or do not gain full faecal continence until late adolescence if at all (Theocharatos & Kenny 2008). There is now greater understanding of the genetics and molecular pathology of this disease, and stem cell treatment may be used in the future, which would avoid the need for surgery and the known risk of faecal incontinence (Gershon 2007).

Exomphalos and gastroschisis

Both anomalies occur at the end of the first trimester and involve a herniation of abdominal contents, either through the base of the umbilical cord (exomphalos) or through a defect in the anterior abdominal wall (gastroschisis). The incidence is approximately 1 per 5000–6000 neonates. There are raised maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein levels and diagnosis can be confirmed early by ultrasound scan.

Exomphalos has a covering of fused peritoneum and amnion, which may rupture during delivery. In up to 75% of cases there are associated chromosome or congenital abnormalities, particularly involving the alimentary tract, heart and genitourinary system.

The herniated viscera in gastroschisis are not protected by a covering sac and may appear oedematous or inflamed at birth. The blood supply can be disrupted to parts of the gut, resulting in necrosis, necessitating resection. If large lengths of bowel are involved, malabsorption syndrome may result. Teratogens have been implicated in its aetiology.

Babies with this condition should be delivered in a specialist centre. At birth, the defect should be covered with sterile ‘cling film’, or the baby’s legs and abdomen placed in a special surgical plastic bag up to the armpits. The main aims are to avoid overhandling of the herniated contents, prevent infection, and reduce heat and evaporative fluid loss. Surgery will attempt to replace as much of the abdominal contents as possible, but may need to be performed in stages over subsequent months or years. Survival rates for these conditions are 90–100% in the absence of other anomalies.

Abnormalities of the genitourinary system

The possibility of an abnormality of the genitourinary system should be considered if only one artery is found in the umbilical cord, and the midwife must monitor the newborn to confirm that urine is passed within 24 hours of birth. If urine is not passed, or the baby is dribbling urine constantly rather than a direct stream of urine, a paediatrician should be informed immediately for further investigation.

Posterior urethral valves (PUV)

Anterior urethral valves (AUV) is very rare. PUV is characterized by valves in the urethra that prevent the flow of urine from the bladder, resulting in bladder distension and back-pressure on the kidneys, leading to hydronephrosis. This condition is found only in male infants, occurring in 1 in 8000 births.

If undetected by antenatal ultrasound, severe renal damage may occur. Fetal surgery can alleviate the blockage, eliminating the need for elective preterm delivery. Sometimes PUV is not diagnosed until later in life.

Hypospadias and epispadias

Hypospadias is a malformation in which the urethral meatus opens on the ventral surface of the penis or, in severe cases, on the perineum. The rarer condition, epispadias, where the meatus opens on the dorsal surface, is usually part of a bladder exstrophy syndrome.

Surgical correction is required in both cases, and circumcision should not be performed prior to this, as the tissue will be required for repair. The nearer the meatus is to the tip of the penis, the less severe the problem and less urgent the surgery, providing there is no urinary obstruction.

Autosomal polycystic kidney disease (APKD)

There are two main types of autosomal polycystic kidney disease – recessive (ARPKD) and dominant (ADPKD).

ARPKD occurs in 1 : 20,000 live births and the fetus presents in utero with enlarged, echogenic kidneys and oligohydramnios. Approximately 30% of these neonates die following birth, from associated pulmonary hypoplasia. Survivors display a range of renal and hepatic symptoms, the severity of which dictates the course of their condition.

ADPKD is more common, occurring in 1 : 500–1000 neonates, and typically involves progressive cyst formation in many organs, particularly the kidneys and liver, and results in renal failure in late middle age.

Renal agenesis

This is the developmental absence of one or both kidneys due to failure of the ureteral bud to develop embryologically, or regression of a dysplastic kidney. It is found in approximately 1 : 1500 antenatal ultrasound scans and if one kidney is present, is usually asymptomatic in the neonate.

There is a high association with other congenital anomalies, particularly genitourinary and musculoskeletal because they develop at the same time. Diagnosis is often incidental in the investigation of other disorders. Extra strain is placed on the solitary kidney, which commonly results in renal damage.

Ambiguous genitalia (‘disorders of sexual development’)

Formerly known as intersex disorders, these are congenital conditions in which development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex is atypical. Genitalia can appear ambiguous at birth; a small penis can be confused with a large clitoris, while a bifid scrotum may resemble the labia majora. True hermaphroditism, in which both male and female genital organs are present, is very rare. Advances in identification of molecular genetic causes of these conditions has resulted in the traditional terminology – that is, hermaphroditism, pseudo-hermaphroditism and intersex disorders – becoming controversial because they are confusing and can be potentially stigmatizing; the preferred term is now ‘disorders of sexual development’ (Lee et al 2006).

If the genitalia are ambiguous at birth, the midwife must inform a senior paediatrician immediately. The sex of the child will usually be determined after clinical, genetic and biochemical investigations. Sometimes the sex cannot be determined, which is extremely distressing for parents. In this situation, parents should be advised to delay registering the birth until a decision is made about gender assignment (legally it is very difficult to alter a birth certificate at a later date).

Gender assignment recommendations in the newborn will depend on the diagnosis and will be based on genital appearance, surgical options, the need for lifelong replacement therapy and potential fertility. Decisions about gender assignment should also reflect family views and cultural background. Disorders of sexual development will cause parents extreme distress because it is a lifelong condition with profound pyscho-social implications at all stages of life. Specialist, multidisciplinary management is required to provide the necessary information and support, initially to parents and eventually to the child/adult (Lee et al 2006).

Abnormalities of the limbs

Limb reduction deformities

In minor cases, these deformities are confined to one or more digits. More severe deformities may involve part or all of the limb. Teratogenic drugs taken in early pregnancy have been cited as a common cause – the best known of these being the antiemetic drug thalidomide. Amniotic band syndrome is another possible cause.

Amniotic band syndrome (ABS)

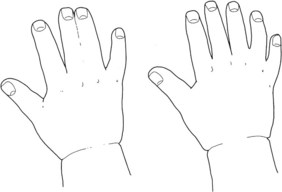

This rare condition is caused by strands of the amniotic sac separating and entangling digits, limbs, or other parts of the fetus, causing a constriction ring. The cause of the amniotic tearing is unknown and it is difficult to detect on ultrasound. The complications from ABS range from mild to severe, including syndactyly (Fig. 48.2) or amputations of fingers or toes, and clubbed feet or limb amputations (Schwarzler et al 1998).

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

Early clinical trials of CVS suggested an association between CVS and a slightly increased risk for limb abnormalities (such as missing or short fingers and toes). These anomalies were only present when CVS was carried out prior to 10 weeks’ gestation. The results were not considered conclusive (WHO 1992) but CVS is now only carried out after 10 weeks’ gestation.

Congenital dislocation of the hip (CDH)

In this condition, one or both hips are abnormally developed, with the head of the femur partially or wholly displaced from the acetabulum. Incidence is approximately 1 : 1500 births. The condition is usually of genetic origin but it may be associated with breech presentation and oligohydramnios.

Ortolani and Barlow tests assess the hips for flexion and abduction to 90 degrees, without dislocation. Eighty per cent of hips are dislocatable at birth but normalize by 2 months of age. These tests should be carried out by a practitioner trained and skilled in this examination (see Ch. 41).

Early detection of CDH is essential to avoid long-term problems when the child begins to walk. Late diagnosis may necessitate 6–12 months in a hip spica, or, in the older child, long periods of traction or an open hip reduction. Ultrasound scanning of the hip joint confirms diagnosis and should routinely be performed when risk factors are present or this condition is suspected. Early orthopaedic referral is crucial, as a neonatal splint may be required.

Achondroplasia

Achondroplasia (dwarfism) (Fig. 48.3) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by abnormal growth of cartilage and bone and occurs in approximately 1 : 25,000 births. The clinical features of achondroplasia are usually short stature, short limbs, and a relatively large head (megacephaly) which may be worsened by hydrocephalus. Neurological problems exist in 20–40% of cases, but intelligence is usually normal (Horton et al 2007).

Chromosomal abnormalities

Trisomy 21 (Down or Down’s syndrome)

This genetic disorder results in well-recognized clinical features (see Fig. 48.4) and varying degrees of intellectual disability. The incidence of trisomy 21 is known to increase significantly with increasing maternal age and amongst very young mothers. There are three recognized forms:

Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome)

Edwards syndrome has an incidence of about 1 : 5000. It has well-recognized clinical features:

Most of these children have severe congenital heart disease and gastrointestinal anomalies and die within the first year. There is often a single umbilical artery.

Trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome)

Patau syndrome is relatively rare, with an incidence of about 1 : 14,000. The face is abnormal with a sloping forehead, bilateral cleft lip and/or palate, and malformed ears. Polydactyly is a common feature and the infant has prominent heels, rocker-bottom feet and a single umbilical artery. The brain is poorly developed and cardiac anomalies are common.The prognosis for these children is poor, with few living beyond 3 years.

Potter syndrome

This condition is incompatible with sustained life. Typical features include low-set ears, furrows under the wide-set eyes, a beaked nose, and a failure to pass urine following birth owing to renal agenesis (absence of both kidneys). There are only two vessels in the umbilical cord. Associated pulmonary hypoplasia frequently manifests itself in asphyxia at birth.

Turner syndrome

Turner syndrome – XO – only affects female infants and occurs in approximately 1 : 2500 live female births. One of the X chromosomes is missing or abnormal, manifesting itself with short stature, underdeveloped ovaries, and infertility. Many affected fetuses will spontaneously abort. Those who survive are of low birthweight, and have a webbed neck and oedema of the lower limbs. They demonstrate normal intelligence, but have a reduced life expectancy that may be related to an increased incidence of congenital heart disease, particularly coarctation of the aorta.

Fetal surgery

Fetal surgery is attempted in conditions where it is considered prenatal repair or intervention will significantly reduce the mortality or morbidity of that fetus – for example, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, cystic adenomatoid malformations, and obstructive uropathy (Kumar & O’Brien 2004).

The greatest problems associated with these procedures are the high risks of precipitating preterm delivery and fetal loss (Kimber et al 1997). Open surgical procedures require a classical caesarean section and necessitate a repeat caesarean section for delivery. Open fetal surgery is relatively safe for the mother, but safety and effectiveness of the surgery for the fetus is variable and depends upon the specific procedure, gestational age and condition of the fetus. Laparoscopic techniques have been developed for many conditions and are improving fetal outcome, for example, vesico-amniotic shunt for a lower urinary tract obstruction such as posterior urethral valves (NICE 2006).

Animal experiments continue to develop techniques and technology for prenatal surgery. Long-term risks and benefits are not yet fully known for these procedures, but trials are in progress; for example, myelomeningocele reconstruction is one of the most reviewed operations and has shown some neurological benefits in survivors (NICHD 2010, Sutton et al 2001).

The physiology of wound healing in a fetus is known to be different from that in adults and results in scarless wound repair (Samuels & Tan 1999). Animal studies suggest that the advantages of this are particularly relevant in the repair of cleft lips and other disfiguring anomalies (Weinzweig et al 1999).

Neonatal surgery

Many of the major anomalies requiring surgical correction can be identified within the first or early second trimesters by ultrasound scanning. Early diagnosis enables counselling of the parents regarding the prognosis, informed choices regarding the pregnancy, and specialist perinatal care forward-planning.

To ensure optimal outcomes, in-utero transfer of the baby is recommended, if possible, to ensure that delivery takes place in a regional, specialist centre. For information about pre- and postoperative neonatal care, see website.

Neonatal pain

There has been ongoing controversy for many years over whether or not the fetus and newborn experience pain. Many of the arguments centre on what constitutes pain. Not all stimuli are painful; some may cause discomfort or a disturbance as opposed to an actual pain. Examples in the neonate would include heel pricks as painful; physical examination as a discomfort and bright lights as a disturbance. These considerations are as relevant to the midwife caring for a healthy neonate at home as to those nursing a sick infant in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Babies can also manifest pain and disturbance following traumatic delivery, such as ventouse, forceps delivery or shoulder dystocia.

Since the late 1990s it has been recommended that consideration should be given to analgesia and sedation for fetuses of 24 weeks’ gestation or over during fetocide and for invasive procedures, including intubation (RCOG 1997). Recent advances in neurobiology and clinical medicine have established that the fetus and newborn may experience acute, established, and chronic pain. Studies have concluded that controlling pain experience is beneficial to short-term and possibly long-term outcomes; however, despite this, pain-control measures are still used infrequently because of unresolved scientific issues (Anand et al 2006).

Strategies for pain relief

use of sucrose (shown to be an effective analgesic agent during painful procedures (Stevens & Ohlsson 2000)

use of sucrose (shown to be an effective analgesic agent during painful procedures (Stevens & Ohlsson 2000)Conclusion

Midwives have a key role in supporting parents of a baby with a diagnosed congenital anomaly and they need to ensure that they have the necessary knowledge and skills to assist parents to reach an understanding of the short-term and long-term implications of any anomaly. In dealing with an unexpected anomaly, midwives need to draw upon their counselling and caring skills to ensure that the woman and family are provided with ongoing information and support, and that long-term services are involved at the earliest stage.