Chapter 40 The pelvic floor

Introduction

Perineal injury has occurred during childbirth throughout the ages and various methods and materials were used by accoucheurs in an attempt to restore the integrity of severely traumatized tissue. The earliest evidence of extensive perineal injury sustained during childbirth exists in the mummy of Henhenit, a Nubian woman aged approximately 22 years, from the harem of King Mentuhotep II of Egypt, 2050 BC (Derry 1935, Graham 1950, Magdi 1949). Despite the fact that maternity care has greatly improved over the past decade, women continue to suffer the consequences of pelvic floor damage resulting from childbirth.

The pelvic floor

The development of the upright posture in humans has been the dominant factor in the evolution of the pelvic floor (Benson 1992). Its main function is to provide support for the pelvic and abdominal organs and it must be strong to oppose the forces of gravity and increases in abdominal pressure. Childbirth is a known source of pelvic floor damage, causing muscle weakness, incontinence, and prolapse of the pelvic organs.

The midwife must have a sound understanding of the structure and function of the pelvic floor in order to apply this knowledge to minimize any associated morbidity during the process of childbirth.

Structure

The ischial spines are key landmarks in understanding the location and structure of the pelvic floor. They lie laterally, in a plane which spans the pelvic cavity where many important parts of the pelvic floor are attached (Benson 1992). The soft tissues, which form the pelvic floor, fill the outlet of the bony pelvis forming a ‘sling’, which is higher posteriorly (Verralls 1993). In the female, the urethra, vagina, and rectum pass through its structures. It consists of the following six layers extending from the pelvic peritoneum above to the skin of the vulva, perineum, and buttocks below:

Pelvic peritoneum

This forms a smooth covering over the uterus and fallopian tubes. Anteriorly it forms the uterovesical pouch and covers the upper surface of the bladder. Posteriorly it forms the pouch of Douglas. Laterally it covers the fallopian tubes and forms the broad ligaments, which do not act as supports.

Pelvic fascia

This connective tissue fills the space between the pelvic organs lining the pelvic cavity walls. Its function is to provide support for the organs, whilst at the same time allowing them to move within the limits of normal function (Verralls 1993). In areas where extra support is needed, it thickens to form the pelvic ligaments:

Deep muscle layer

This is formed mainly from symmetrically paired muscles, varying in thickness, collectively known as the levator ani. They arise at the inner circumference of the true pelvis from the white line of the obturator fascia and decussate midline between the urethra, vagina, and rectum. The muscle fibres pass downwards and backwards and are inserted medially into the upper vagina, perineal body, anal canal, anococcygeal body, coccyx, and lower borders of the sacrum.

The main function is to provide a strong sling to support the pelvic organs and to counteract any increase in the intra-abdominal pressure during coughing and laughing. When the levator ani is contracted, the pelvic floor and perineum are lifted upwards – an important mechanism to maintain continence.

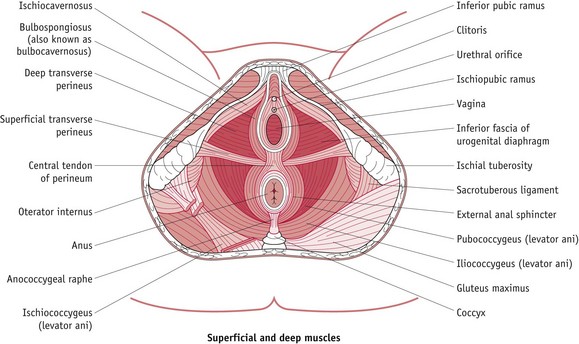

The deep muscles are named after the corresponding fused bones of the innominate bone (pubis, ilium and ischium) (Fig. 40.1):

pass posteriorly below the bladder on either side of the urethra, upper vagina and anal canal to the anococcygeal body and coccyx

pass posteriorly below the bladder on either side of the urethra, upper vagina and anal canal to the anococcygeal body and coccyx fibres cross medially and join those from the opposite sides to form U-shaped slings around the urethra, vagina, and rectum

fibres cross medially and join those from the opposite sides to form U-shaped slings around the urethra, vagina, and rectum the puborectalis muscle forms a loop around the anorectal junction and its posterior fibres communicate with the external anal sphincter

the puborectalis muscle forms a loop around the anorectal junction and its posterior fibres communicate with the external anal sphincter on dissection, are paler in colour, suggesting they are fast-twitch muscle capable of rapid contraction (Benson 1992)

on dissection, are paler in colour, suggesting they are fast-twitch muscle capable of rapid contraction (Benson 1992)

Figure 40.1 Muscles of the pelvic floor seen in the female perineum.

(From Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, 7th edn, by Tortora, G.J. and Grabowski, S.R.

Blood, lymph and nerve supply

Blood supply is via the pudendal arteries and branches of the internal iliac artery, and the venous drainage is via corresponding veins. Lymphatic drainage is via the inguinal and external internal iliac glands and the nerve supply is via the third and fourth sacral nerves.

Superficial perineal muscles

These are less important than the levator ani muscles; but contribute to the overall strength of the pelvic floor and likely to be damaged during vaginal delivery (Fig. 40.1):

extend from central point in the perineal body, and encircle the vagina and urethra before inserting anteriorly into the corpora cavernosa of the clitoris

extend from central point in the perineal body, and encircle the vagina and urethra before inserting anteriorly into the corpora cavernosa of the clitorisSphincters

in females, the EAS is shorter anteriorly and fuses with the bulbocavernosus and transverse perinei in the lower part of the perineum (Sultan et al 1994a)

in females, the EAS is shorter anteriorly and fuses with the bulbocavernosus and transverse perinei in the lower part of the perineum (Sultan et al 1994a) the deep EAS is inseparable from the puborectalis muscle and posteriorly is attached to the coccyx by some of its fibres

the deep EAS is inseparable from the puborectalis muscle and posteriorly is attached to the coccyx by some of its fibresPerineal body

This is a triangular-shaped structure consisting of muscular and fibrous tissue, situated between the vagina and the anal canal, with the ischial tuberosities laterally. Each side of the triangle is approximately 3.5 cm in length: the base is the perineal skin and the apex points inwards. This is an integral part of the pelvic floor, since it is the central point where the levator ani and most of the superficial muscles unite. Blood is supplied by the pudendal arteries and venous drainage is into the corresponding veins. Lymph drains into the inguinal and external iliac glands. The nerve supply is derived from the perineal branch of the pudendal nerve.

Midwifery implications

During pregnancy, the hormone relaxin softens the pelvic muscles and ligaments, allowing them to stretch during parturition to allow the passage of the term infant. After delivery, the pelvic floor is able to contract back to resume its original supporting function in a surprisingly short time, because of its remarkable elasticity.

Prolonged, repeated or extreme stretching of the pelvic floor muscles may cause permanent damage, resulting in loss of tone and elasticity. If these muscles fail to support the pelvic organs, prolapse results, though this may not manifest until later life when postmenopausal oestrogen deficiencies may predispose to muscle weakness (Haadem et al 1991). (For long term effects, please see website.)

Perineal trauma

Anterior perineal trauma is any injury to the labia, anterior vagina, urethra, or clitoris and is associated with less morbidity.

Posterior perineal trauma is any injury to the posterior vaginal wall, perineal muscles, or anal sphincters (external and internal) and may include disruption of the rectal mucosa.

Perineal trauma may occur spontaneously during vaginal birth or through intentional surgical incision (episiotomy) by the midwife or obstetrician to increase the diameter of the vulval outlet and facilitate delivery.

Prevalence

Over 85% of women who have a vaginal birth will sustain some form of perineal trauma (McCandlish et al 1998) and up to 69% of these will require stitches (McCandlish et al 1998, Sleep et al 1984).

Rates will vary considerably according to individual practices and hospital policies throughout the world, illustrated by wide variations in episiotomy rates internationally from 8% in the Netherlands, 13% in England and 43% in the USA, to 99% in the Eastern European countries (Graham & Graham 1997, Graves 1995, Statistical Bulletin 2003, Wagner 1994).

Certain intrapartum interventions or alternative forms of care may also affect the rate and extent of perineal trauma; including continuous support during labour, delivery position, epidural anaesthesia, style of pushing, restricted use of episiotomy and ventouse delivery (Kettle 1999, 2001).

Aetiology and risk factors

Perineal trauma occurs during spontaneous or assisted vaginal delivery and is usually more extensive after the first vaginal birth (Sultan et al 1996). Women who have no visible damage may be subject to transient pudendal or peripheral nerve injury due to prolonged active pushing or pressure exerted by the fetal head on the surrounding structures (Allen et al 1990).

Associated risk factors include:

Short- and long-term effects

In the UK, approximately 23–42% of women will have perineal pain and discomfort up to 10–12 days following vaginal delivery and 7–10% of these women will continue to have long-term pain up to 18 months post partum (Glazener et al 1995, Gordon et al 1998, Grant et al 2001, McCandlish et al 1998, Mackrodt et al 1998, Sleep et al 1984).

In terms of sexual function, 62–88% of women will resume intercourse by 8–12 weeks postpartum, though 17–23% of women experience superficial dyspareunia at 3 months after delivery and 10–14% will continue to have pain at 12 months (Barrett et al 2000, Glazener 1997, Gordon et al 1998, Grant et al 2001, Kettle et al 2002, Mackrodt et al 1998).

Estimation of the extent of urinary and faecal incontinence is difficult because of under-reporting of these problems due to the sensitive nature of the complaint (Sultan et al 1996). One survey found that 15.2% of participating women (number 1782) reported stress incontinence which started for the first time within 3 months of the baby’s birth, and 75% of these still had problems over a year later (MacArthur et al 1993). Sleep & Grant (1987) and MacArthur et al (1997) found that up to 4% of women reported occasional loss of bowel control.

Antenatal preparation

The midwife can contribute to reducing the extent and rate of perineal trauma by reviewing the woman’s lifestyle and giving appropriate advice regarding diet, smoking, exercise, and perineal massage. Being healthy and well nourished should ensure optimum condition of the perineal tissue prior to labour. Current evidence supports the use of antenatal perineal massage for preserving the integrity of the perineum, particularly in women having their first vaginal birth (Labrecque et al 2000, 2001). Women wishing to carry out this practice should be instructed to perform perineal massage from 34–35 weeks’ gestation for 5–10 minutes daily using sweet almond oil (Labrecque et al 1999, Shipman et al 1997).

Midwives should also instruct and encourage women to carry out regular antenatal pelvic floor exercises to strengthen the muscles in preparation for childbirth and to continue these excercises into the postnatal period to reinnervate and increase the pelvic floor muscle tone in order to reduce any associated morbidity such as stress incontinence (Mason et al 2001).

Spontaneous trauma

Tears usually extend downwards from the posterior and/or lateral vaginal walls, through the hymenal remnants, midline downwards towards the anal margin, in the weakest part of the stretched perineum. Occasionally, they occur in a circular direction, behind the hymenal remnants, extending bilaterally upwards towards the clitoris and detaching the lower third of the vagina from the underlying structures (Sultan et al 1994a). This complex trauma causes vast disruption to the perineal body and muscles but the perineal skin may remain intact, making it difficult to repair.

Cervical tears

A cervical tear may result if an instrumental delivery (forceps or ventouse) is attempted before the cervix is fully dilated or the woman forcibly pushes the fetus through a cervix that is incompletely dilated (Oats & Abraham 2010).

Bleeding is usually very severe and will persist despite the uterus being well contracted. Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) resulting from a cervical tear must be managed appropriately and efficiently according to guidelines (NICE 2007), as mismanagement can cause maternal mortality (see Ch. 68). Once the maternal condition has been stabilized, a skilled operator must repair the cervical tear in a theatre with good lighting, appropriate assistance, and adequate anaesthesia.

Surgical incision (episiotomy)

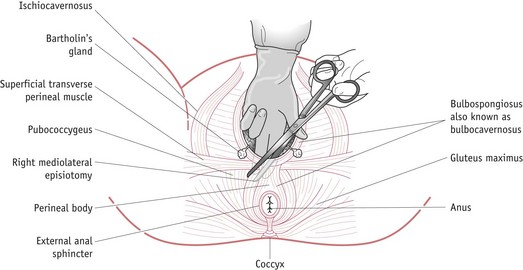

Episiotomy is a surgical incision of the perineum made to increase the diameter of the vulval outlet during childbirth.

Straight, blunt-ended Mayo episiotomy scissors are usually used because it is thought that there is less risk of accidental damage to the baby, and haemostasis of the cut tissue is promoted by the crushing action as the incision is made. Some professionals favour the scalpel and feel that it minimizes trauma to the tissues which allows better healing of the perineal wound, though no data support the validity of either of these claims (Sleep et al 1989).

An episiotomy should not be carried out routinely during spontaneous vaginal birth, and should only be performed if there are specific clinical needs as documented below. It should not be offered routinely following previous third- or fourth-degree trauma.

Prior to performing the incision, informed consent must always be obtained from the woman and analgesia should always be administered, except in an emergency if there is acute fetal compromise (NICE 2007).

There are two main types of incision:

Figure 40.2 Diagrammatic representation of a right mediolateral episiotomy showing the muscles involved when the incision is made.

Reflective activity 40.1

Find out what the episiotomy rate is for spontaneous vaginal deliveries in the maternity unit where you are working.

Timing of the incision

An episiotomy must only be made when the presenting part is distending the perineal tissues; otherwise it will fail to accelerate delivery and excessive bleeding may occur.

Indications

The following are not absolute, and clinical discretion must always be used:

NB: There is no scientific evidence to support the routine procedure of episiotomy to prevent intracranial haemorrhage in preterm deliveries (Woolley 1995).

Risks

NB: The risks are clearly increased with a high episiotomy rate.

Prior to performing the episiotomy, the midwife must prepare the delivery trolley and equipment according to the practice policies and guidelines of the individual employing policies. Safety glasses and gloves must be worn during all obstetric procedures, to protect the operator against HIV and hepatitis infection. The woman’s dignity and comfort must be maintained throughout the procedure (see Table 40.1). There is some debate about the incision to be used – please see website.

Table 40.1 Procedure for mediolateral episiotomy

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Explain the procedure and indications to the woman and her partner | 1. To reassure the woman and confirm consent |

| 2. Place the woman in a comfortable position with her legs open | 2. To ensure that the whole perineal area is accessible |

| 3. Cleanse the perineal area using the agreed aseptic technique | 3. To minimize infection |

| 4. Place the index and middle fingers into the vagina between the presenting part and perineum. Insert the needle fully into the perineal tissue starting at the centre of the fourchette and directing it midway between the ischial tuberosity and anus | 4. To protect the baby from accidental damage |

| 5. Draw back the plunger of the syringe prior to injecting 5–10 mL of local anaesthetic, 1% lidocaine, slowly into the tissue as the needle is withdrawn | 5. To check that the lidocaine is not accidentally injected into a blood vessel and to provide effective anaesthesia to facilitate a pain-free incision |

| 6. Insert the middle and index fingers into the vagina and gently pull the perineum away from the presenting fetal part | 6. To protect the presenting fetal part from accidental damage |

| 7. Perform the incision when the presenting part has distended the perineum | 7. To minimize pain and blood loss |

| 8. Insert the open scissors between the two fingers and make the incision in one single cut | 8. To ensure a straight cut, minimize severe perineal damage and facilitate optimum anatomical realignment |

| 9. Perform the incision – it should extend at least 3–4 cm into the perineum. The incision should start midline from the centre of the fourchette and then extend outwards in a mediolateral direction, avoiding the anal sphincter(s). Withdraw the scissors carefully |

9. To increase the vulval outlet and facilitate delivery |

| 10. Control delivery of the presenting part and shoulders | 10. To prevent sudden expulsion of the presenting part and extension of the episiotomy incision |

| 11. Apply pressure to the episiotomy incision between contractions if there is a delay in delivering the baby | 11. To control bleeding from the wound |

| 12. Thoroughly inspect the vagina and perineum, including a rectal examination, following completion of the third stage | 12. To identify the extent of trauma prior to repair |

Episiotomy rate

There seems to be no consensus as to the recommended episiotomy rate. The World Health Organization suggests that an episiotomy rate of 10%, for normal deliveries, would be ‘a good goal to pursue’ (WHO 1996).

Discussion

Episiotomy has been described as the unkindest cut, but with limited evidence about use and efficacy, has been introduced into maternity care in the UK (see website).

Major variations in current national rates indicate uncertain justification for this practice (Audit Commission 1997).

Some argue that episiotomy causes more pain, weakens pelvic floor structures, interferes with breastfeeding and increases sexual problems (Greenshields & Hulme 1993, Kitzinger & Walters 1981). Others argue that episiotomy reduces the incidence of severe perineal trauma and prevents overstretching of pelvic floor muscles, so reducing the risk of stress incontinence and uterine prolapse (Donald 1979, Flood 1982). However, research carried out by Klein et al (1994) found that women who delivered with an intact perineum or spontaneous perineal tear had less pain, stronger pelvic floor muscles, and better sexual function when compared to those with an episiotomy, at 3 months postpartum.

Midwives should restrict the use of episiotomy to specific fetal and maternal indications. Previous randomized controlled trials comparing restricted to liberal use of episiotomy found that a restricted policy is associated with lower rates of posterior perineal trauma, less suturing, and reduction in pain and healing complications (Carroli & Belizan 2001). This results in a lower rate of maternal morbidity and may have significant cost-saving implications for suture materials (Carroli & Belizan 2001, Sleep et al 1984).

Suturing the perineum

In the UK, the theory and technique of perineal repair has been included in the midwifery curriculum since 1983 (Silverton 1993). By 1986, midwives were repairing perineal trauma in over 60% of consultant units in England and Wales (Garcia et al 1986), thus achieving increased continuity of care, prompt sensitive repair, and increased job satisfaction.

Suture materials for primary repair of perineal trauma

The ideal suture material should cause minimal tissue reaction and be absorbed once it has served its purpose of holding the tissue in apposition during the healing process (Taylor & Karran 1996). Well-aligned perineal wounds heal by primary intention with minimal complications, usually within 2 weeks of suturing. However, if the stitches remain in the tissues for longer than this period, they act as a foreign body and may impair healing, causing irritation. Local infection of the stitches will prolong the inflammatory phase and cause further tissue damage, which will delay collagen synthesis and epithelialization (Flanagan 1997).

Perineal repair using absorbable synthetic material, such as polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) or polyglycolic acid (Dexon), reduces short-term pain, though long-term effects are less clear and there are some concerns regarding the need to remove sutures up to 3 months after delivery (Kettle & Johanson 2001).

Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) – carried out by Gemynthe et al (1996), McElhinney et al (2000) and Kettle et al (2002) – compared rapidly absorbed polyglactin 910 (Vicryl Rapide) to standard polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) and found no overall difference in short-term perineal pain between groups, but a significant reduction in the need for suture removal up to 3 months following childbirth with the rapidly absorbed material. Two of the trials (Gemynthe et al 1996, Kettle et al 2002) found a significant reduction in ‘pain when walking’ at 10–14 days postpartum. One trial (McElhinney et al 2000) reported a reduction in superficial dyspareunia at 3 months postpartum. This evidence suggests that Vicryl Rapide is the ideal suture material for perineal repair (NICE 2007).

The arguments for recommended suture techniques for primary repair of perineal trauma are given on the website.

Non-suturing of perineal skin

Two RCTs compared suturing the vagina and perineal muscles, leaving the perineal skin unsutured, to the conventional method of suturing the vagina, perineal muscles and skin (Gordon et al 1998, Oboro et al 2003). The UK study found no significant difference in perineal pain at 10 days postpartum between groups (Gordon et al 1998), though the Nigerian study indicated a reduction in perineal pain at 48 hours, 14 days, 6 weeks, and 3 months following birth when the skin was left unsutured (Oboro et al 2003).

Tissue adhesive

Two small trials looked at the use of tissue adhesive for closure of perineal skin following second-degree tear or episiotomy (Adoni & Anteby 1991, Rogerson et al 2000). Both trials claim that this method is effective, but the results must be interpreted with caution owing to the poor methodological design of these studies and the small number of participants included.

Procedure (see Table 40.2)

Perineal tears and episiotomies are repaired under aseptic conditions with a good source of light and the mother in a comfortable position so that the trauma can be easily visualized. Lithotomy poles to support the woman’s legs during the repair are unnecessary and might bring back ‘locked in’ memories of sexual abuse, making the woman feel helpless and out of control (Walton 1994). Also, leg restraints (lithotomy poles) cause flexion and abduction of the woman’s hips which results in excessive stretching of the perineum, causing the episiotomy or tear to gape (Borgatta 1989). Apart from being uncomfortable for the woman, this can make the trauma difficult for the operator to realign and suture. There is no need to use a tampon.

Table 40.2 Procedure for continuous method of perineal repair

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Explain the procedure to the woman and her partner | 1. To reassure the woman and confirm consent |

| 2. Check maternal baseline observations and PV blood loss | 2. To ensure that the woman’s general condition is stable prior to commencing the repair |

| 3. Assess the extent of perineal trauma | 3. To ensure the repair is not beyond the operator’s level of competence |

| 4. Ensure that the woman is in an appropriate position | 4. To ensure that the whole perineal area is accessible |

| 5. Cleanse the vulva and perineal area. Drape the area with a sterile lithotomy towel | 5. To minimize risk of infection |

| 6. Identify anatomical landmarks. These may include hymenal remnants and tissue of different colour | 6. To aid the operator to correctly align and approximate the traumatized tissue NB: Misalignment may cause long-term morbidity such as dyspareunia |

| 7. Draw back the plunger of the syringe prior to injecting 10–20 mL of local anaesthetic, 1% lidocaine, slowly into the traumatized tissue, ensuring even distribution | 7. To check that the lidocaine is not accidentally injected into a blood vessel and to provide effective anaesthesia to facilitate a pain-free repair |

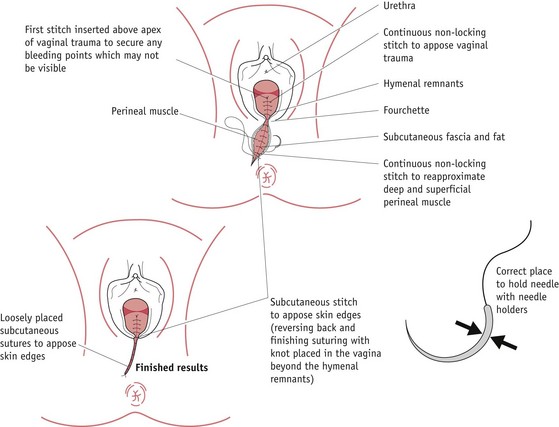

| 8. Identify the apex of the vaginal trauma and insert the first stitch 5–10 mm above this point | 8. To ensure haemostasis of any bleeding vessels that may have retracted beyond the apex |

| 9. Suture posterior vaginal trauma using a loose continuous non-locking stitch. Continue to the hymenal remnants taking care not to make the stitches too wide | 9. To appose the edges of traumatized vaginal mucosa and muscle without causing shortening or narrowing of the vagina |

| 10. Ensure that each stitch reaches the trough of the traumatized tissue | 10. To close dead space, achieve haemostasis and prevent paravaginal haematoma formation |

| 11. Visualize the needle at the trough of the trauma each time it is inserted | 11. To prevent sutures being inserted through the rectal mucosa NB: A recto-vaginal fistula may form if this occurs |

| 12. Bring the needle through the tissue underneath the hymenal ring and continue to repair the deep and superficial muscles using a loose continuous stitch | 12. To realign the perineal muscles, close the dead space, achieve haemostasis and minimize the risk of haematoma formation |

| 13. Reverse the stitching direction at the inferior aspect of the trauma and place the stitches loosely in the subcutaneous layer, approximately 5–10 mm apart | 13. To appose skin edges and complete the perineal repair |

| 14. Do not pull the stitches too tight | 14. To prevent discomfort from overtight sutures if reactionary oedema and swelling occur |

| 15. Complete the subcutaneous repair to the hymenal ring, swing the needle under the tissue into the vagina and complete the repair using a terminal loop knot | 15. To secure the stitches |

| 16. Inspect the repaired perineal trauma | 16. To ensure the trauma has been sutured correctly and that haemostasis has been achieved Check that there is no excessive bleeding from the uterus |

| 17. Insert two fingers gently into the vagina | 17. To confirm that the introitus and vagina have not been stitched too tightly |

| 18. Perform a rectal examination | 18. To confirm that no sutures have penetrated the rectal mucosa |

| 19. Cleanse and dry the perineal area. Apply a sterile pad | 19. To minimize infection |

| 20. Check and record that all swabs, needles and instruments are correct | 20. To confirm that all equipment and materials used are complete and accounted for |

| 21. Place the woman in the position of her choice | 21. To ensure that the woman is made comfortable following the procedure |

| 22. Complete the appropriate documentation | 22. To fulfil statutory requirements and to provide an accurate account of the repair |

If the woman has a working epidural, it may be topped up to provide effective perineal area anaesthesia instead of injecting local anaesthetic. Khan & Lilford (1987) recommend that even if an epidural is used, the perineal wound should be infiltrated with normal saline or local anaesthetic to mimic tissue oedema and prevent overtight suturing.

Prior to performing the repair, the midwife must prepare the suturing trolley and check equipment according to individual employing authorities’ practice guidelines. The woman’s comfort and dignity must be maintained throughout the procedure.

The area should be cleaned according to the individual unit’s guidelines; however, a study by Calkin (1996) found that tapwater was just as effective as chlorhexidine antiseptic.

The method of performing the repair is shown in Figure 40.3 and the rationale for each stage of the process is given in Table 40.2.

On completion of perineal repair, the woman should be given advice regarding:

Labial lacerations

These are usually superficial but can be very painful. Some practitioners do not recommend that these are sutured; however, if the trauma is bilateral, sometimes the lacerations heal together over the urethra, causing voiding difficulties.

Non-suturing of perineal trauma

The effects of not suturing deeper perineal trauma, such as second-degree tears or episiotomies, have not yet been robustly evaluated, though some practitioners appear to have adopted a non-suturing policy without reliable evidence to support their practice (see website).

Until robust evidence is available to support this controversial practice, midwives must be cautious about leaving trauma other than small first-degree tears unsutured unless it is the explicit wish of the woman. There is an urgent need for a large randomized controlled trial to be undertaken comparing non-suturing versus suturing of second-degree perineal trauma with long-term follow-up. Practice must be based upon scientific principles.

Third- and fourth-degree tears

The reported incidence of clinically detectable anal sphincter injuries following childbirth ranges from 0.5% to 3% (Sultan et al 1994b, Tetzschner et al 1996), though the full extent of the problem is probably underestimated. Some third-degree tears may not be recognized following vaginal delivery (Andrews et al 2006, Groome & Paterson Brown 2000). Studies found that with increased vigilance and improvement in clinical skills, the detection of anal sphincter disruption could be vastly improved. If this type of trauma is not recognized after delivery, women can be left with long-term problems including incontinence of faeces and flatulence. Anal incontinence following anal sphincter injury varies between 7% and 59% (Goffeng et al 1998, Kamm 1994, Tetzschner et al 1996), but again may be higher due to non-reporting. In one study, only one-third of the participants with faecal incontinence had ever discussed their problem with a physician (Johanson & Lafferty 1996).

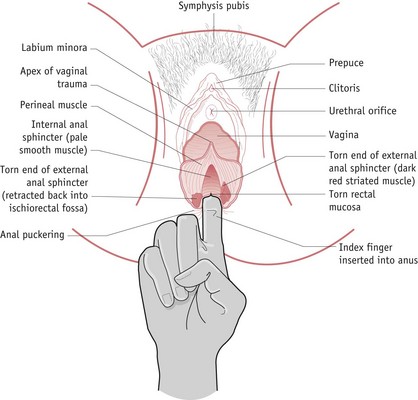

Midwives and medical staff must be aware of this type of trauma and be adequately trained to identify anal sphincter injuries when they occur (Fig. 40.4). (See website for associated risk factors.)

All perineal trauma must be thoroughly examined with the aid of a good light source and the extent of injury must be accurately documented in the hospital case notes. When assessing perineal injury after delivery, a rectal examination should be routinely performed to avoid missing anal sphincter trauma. If a third- or fourth-degree tear is suspected, it must be checked by an independent experienced practitioner.

Identification of anal sphincter injury

For further information on third- and fourth-degree repair, please see website.

Professional and legal issues

Litigation is a major concern for all practitioners; however, a competent midwife has little to fear if she works within the parameters of the employing authority’s policies and guidelines, and the midwives’ rules (NMC 2004). In an action for damages, practitioners may be held personally liable if it can be shown that they failed to exercise appropriate skills and work within their professional boundaries.

Conclusion

Mismanagement of perineal trauma has a major impact on women’s health and has significant implications for health service resources. Midwives must base their practice on current research evidence and be aware of problems associated with perineal trauma and repair. Careful identification and repair of trauma by a skilled practitioner may avoid problems. It is important that prompt sensitive treatment is provided for those women with problems in order to reduce the morbidity associated with perineal injury following childbirth.