Chapter 68 Complications of the third stage of labour

Postpartum haemorrhage

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a significant cause of maternal mortality and morbidity (Knight et al 2008, Lewis 2007). It may happen without warning after any delivery. The only professional in attendance for the majority of births is the midwife, whose prompt action may spare the mother dangerous blood loss and save her life. It is essential that midwives have a thorough understanding of this subject. Maternity services must have a policy for management of PPH so that all members of the multidisciplinary team work together and attend regular ‘fire drills’ to ensure quick and appropriate responses (Lewis 2007).

Definition

PPH is defined as excessive bleeding from the genital tract occurring any time from the birth of the baby to the end of the puerperium.

Primary PPH is often defined by the estimated blood loss. Traditionally, a loss of 500 mL or more has been regarded as a PPH (WHO 1990), yet this may be considered as a normal physiological blood loss if a woman is not anaemic (Rogers & Chang 2008).

Estimating blood loss after birth is notoriously difficult. Bleeding may be hidden; and if visible, it is likely to be underestimated (Prasertcharoensuk et al 2000, Toledo et al 2007). However, regular clinical simulations may improve blood loss estimation (Bose et al 2006).

Hence, defining PPH by estimating blood loss may have little clinical usefulness, and, therefore, the word ‘excessive’ is used to mean any amount which adversely affects the mother.

When estimating blood loss to define PPH, Coker & Oliver (2006) propose that if blood loss is estimated as 500 to 1000 mL and there are no clinical signs of maternal compromise, staff should be alerted to monitor the woman and be ready for possible action. Should the estimated blood loss be above 1000 mL or the mother shows any sign of compromise, then prompt action must be taken to resuscitate and arrest bleeding. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2009) have used these principles to define minor and major PPH. The guidelines suggest that with a minor PPH (a blood loss of 500 to 1000 mL, with no maternal compromise) basic measures need to be undertaken, and when a major PPH is diagnosed (a blood loss of over 1000 mL or clinical shock present) a full obstetric protocol must be followed (see website).

Causes

PPH may arise from the placental site or from a genital tract laceration, and may be classified by using the ‘4 Ts’ (see website) (Anderson & Etches 2007):

PPH from uterine atony

The immediate cause of primary placental site PPH is failure of the uterus to contract and retract adequately. As there is a placental circulation of approximately 600 mL/min at term (Blackburn 2007), if the uterine arteries are not ligated by the muscle fibres surrounding them, blood loss can be rapid and dangerous. This may occur because the myometrium is atonic, or because retained placental tissue prevents effective uterine contraction.

Prediction and risk factors

It is not possible to predict a PPH accurately, but the risk is increased in certain circumstances:

Prophylaxis

Pregnancy

Preventing PPH begins at the initial booking interview when midwives will identify women at higher risk. Any woman whose history suggests that she is at risk should be booked for a hospital birth where immediate and effective treatment can be provided. Conditions such as anaemia should be treated with iron and folic acid supplements. In severe cases, intramuscular iron or even blood transfusion may be required to raise the haemoglobin levels prior to delivery.

Labour

During labour, careful management will reduce the likelihood of PPH. For women at risk:

The midwife will monitor the progress of labour and avoid dehydration and exhaustion. An obstetrician should be called for signs of prolonged labour (Ch. 63). An oxytocin infusion may be required which should be maintained for at least 1 hour after the end of the third stage. The bladder should be kept empty, as a full bladder may impede efficient uterine action.

Correct management of the third stage of labour is crucial. The midwife should discuss the management of the third stage with the woman, preferably before labour commences. Active management of the third stage is associated with reduction in PPH (Prendiville et al 2000). The use of fundal massage following the delivery of the placenta is recommended to reduce the risk of PPH (Hofmeyr et al 2008). Breastfeeding or nipple stimulation will also help the uterus to contract, though it is not an effective treatment for PPH. Ergometrine maleate 500 mcg should be available. Accurate estimation of blood loss and timely observation of vital signs will enable early detection and prompt treatment.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2005) guidelines suggest that women at risk of haemorrhage during or following caesarean section may be offered intra-operative blood cell salvage (see website). Guidelines for women who refuse blood transfusion have been recommended by a previous Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report (Lewis 2004) (see website).

Treatment

The principles of management are:

Units vary in the management of PPH, especially with pharmacological protocols (Winter et al 2007). This may be due to limited research on the specific treatment combinations for PPH. Midwives should follow their hospital guidelines as appropriate.

Before delivery of the placenta

Prolonged brisk bleeding prior to the delivery of the placenta should alert the midwife to take action. Skilled medical assistance should be summoned immediately, whilst the midwife must remain with the mother for support and commence treatment. If at home, the midwife should deliver the placenta, if possible, before transferring the woman to hospital.

The degree of uterine contraction should be assessed. If the fundus feels soft, the first consideration is to stimulate uterine contraction and give an oxytocic drug. Oxytocin 10 international units (iu) may be given intramuscularly, causing the uterus to contract within 2.5 minutes. Syntometrine (oxytocin 5 iu and ergometrine 500 mcg) should be avoided if there is a history of hypertension. There is also some evidence that ergometrine may cause the placenta to become entrapped (Begley 1990, Cotter et al 2001, Hammar et al 1990), thus exacerbating the bleeding.

The bladder should be empty before another attempt is made to deliver the placenta with controlled cord traction and the genital tract should be inspected to exclude traumatic haemorrhage.

If the placenta cannot be delivered, prepare for the doctor to perform a manual removal of the placenta and membranes under anaesthetic. Retained placenta is discussed later.

After delivery of the placenta

The following principles should be applied when a minor PPH is diagnosed. The order in which the actions are to be taken may vary and where possible actions should be taken simultaneously:

Intravenous or intramuscular injection of oxytocin 5–10 iu followed by ergometrine 250–500 mcg. This may be given intramuscularly or, cautiously, intravenously in the absence of hypertension. No more than two doses of ergometrine may be administered (Joint Formulary Committee 2008).

Intravenous or intramuscular injection of oxytocin 5–10 iu followed by ergometrine 250–500 mcg. This may be given intramuscularly or, cautiously, intravenously in the absence of hypertension. No more than two doses of ergometrine may be administered (Joint Formulary Committee 2008).

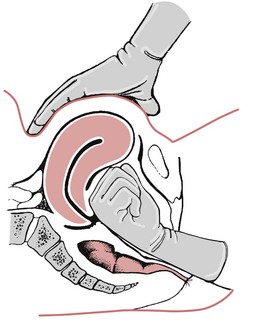

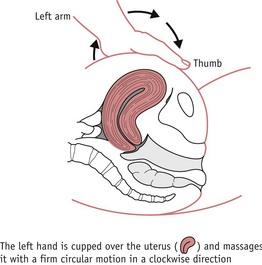

Figure 68.2 ‘Rubbing up’ a contraction. The left hand is cupped over the uterus and massages it with a firm circular motion in a clockwise direction.

(From Boyle (2002) Radcliffe Publishers, with permission.)

It is essential that these steps are taken as soon as the midwife suspects that the uterus is failing to contract and bleeding is unusually heavy. In most cases they are effective if used in good time. Delay will result in further blood loss and the woman’s condition can deteriorate rapidly.

The placenta and membranes are examined to ensure that they are complete. If not, an exploration and evacuation of the uterus is carried out by an obstetrician under anaesthesia.

With PPH, the midwife should not elevate the foot of the bed as this encourages blood to pool within the uterine cavity, which would hinder uterine contraction and retraction. The woman’s legs may be elevated on pillows, taking care to avoid undue pressure on the calves, which would predispose to venous thrombosis.

Further measures

If bleeding continues despite the above treatment, compression of the uterus or main abdominal vessels may be needed.

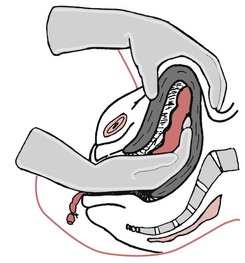

Internal bimanual compression (Fig. 68.3)

A fist is made with the right hand and introduced into the vagina. It is then pushed up towards the anterior vaginal fornix. The left hand dips down behind the uterus and pulls it forwards towards the symphysis. The hands are pushed together, compressing the uterus and placental site. The pressure is maintained until the uterus contracts and remains retracted.

External bimanual compression

The left hand dips down behind the uterus; the right hand is pressed flat on the abdominal wall; the uterus is compressed and, simultaneously, pulled upwards in the abdomen. This compresses the bleeding area while the pulling up of the uterus straightens the kinked uterine veins, allowing free drainage, relieving the congestion and decreasing the bleeding.

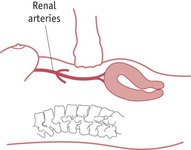

Abdominal aortic compression

This has been used as a short-term emergency measure to control severe haemorrhage while awaiting emergency assistance. The midwife places a fist above the fundus and below the level of the renal arteries. Pressure is directed towards the spine in order to compress the aorta and reduce blood flow to the uterus (Fig. 68.4). Adequacy of compression can be assessed by checking for the absence of femoral pulses (Keogh & Tsokos 1997).

Once bleeding is controlled, uterine contraction is maintained by an intravenous infusion solution of 40 iu of Syntocinon in 500 mL of normal saline at 10 iu per hour. A blood transfusion may be required. If the bleeding persists or recurs, an exploration of the genital tract under general anaesthesia may be required.

Massive obstetric haemorrhage

This is a life-threatening event, characterized by severe maternal compromise. A blood loss of 1000 to 1500 mL or more, or any lesser amount which causes a sustained fall in systolic blood pressure, constitutes a ‘massive obstetric haemorrhage’.

In addition to the measures taken above for a minor PPH, the following should be done:

Carboprost (Hemabate) 250 mcg may be administered by deep intramuscular injection and can be repeated every 15 minutes, up to eight doses (maximum dosage of 2 mg) (Joint Formulary Committee 2008). It may also be injected directly into the myometrium.

Carboprost (Hemabate) 250 mcg may be administered by deep intramuscular injection and can be repeated every 15 minutes, up to eight doses (maximum dosage of 2 mg) (Joint Formulary Committee 2008). It may also be injected directly into the myometrium. Misoprostol (800 mg) may be given rectally. However, there is limited evidence that it reduces blood loss from PPH when used alongside other oxytocics (Hofmeyr & Gülmezoglu 2008).

Misoprostol (800 mg) may be given rectally. However, there is limited evidence that it reduces blood loss from PPH when used alongside other oxytocics (Hofmeyr & Gülmezoglu 2008).Surgical procedures

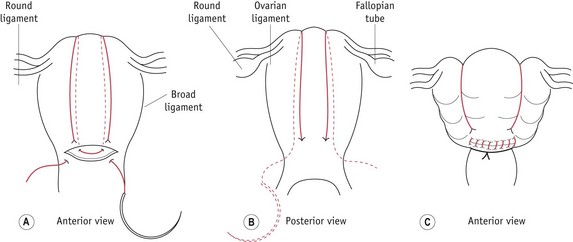

Figure 68.5 B-Lynch suture in the uterus: A. anterior and B. posterior views showing the application of the suture; C. the anatomical appearance after competent application.

(Reprinted from B-Lynch et al 1997, with permission. Illustrations by Mr Philip Wilson FMAA RMIP.)

Radiological procedures

Observations

The mother’s general condition is assessed continuously. It is important to palpate the fundus repeatedly to ensure that it remains well contracted and to observe the amount and nature of the blood loss. Her pulse, blood pressure and oxygen saturations are recorded every 15 minutes until her condition is satisfactory. A fluid balance chart is maintained to record the fluid intake and urinary output. A catheter, attached to a urometer, is needed and urine output is recorded hourly. Central venous pressure should be measured when it is necessary to give large volumes of fluid intravenously, to avoid overtransfusion.

Elevating the woman’s legs may help to maintain core circulation. Oxygen is given by facemask and sedation may be required. The mother needs to be kept dry and comfortable.

The woman may need to be transferred to an intensive care unit.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

DIC is a coagulopathy which results in steady, persistent oozing of blood even though there is adequate uterine contraction and retraction (see Ch. 58). Blood does not clot, venepuncture sites may ooze, and petechiae may appear. DIC occurs as a result of severe haemorrhage, when supplies of circulating fibrinogen and other blood clotting factors become depleted and the coagulation system fails. Hypoxia which accompanies major haemorrhage may cause the local release of thromboplastin from the damaged tissue, triggering the formation of microthrombi all round the body. This further exhausts the circulating coagulation factors. The thrombi will block capillaries, thus causing more tissue damage and release of thromboplastin.

As the condition worsens, blood levels of fibrin degradation products (FDPs) rise. These are toxic to the myometrium and will interfere with efficient uterine contraction and retraction, thus exacerbating haemorrhage. If DIC is allowed to progress, the condition will become uncontrollable and maternal death may ensue.

At every delivery, the midwife should note whether the blood is clotting and whether the clot is firm or friable. Absent or unstable clot formation along with results from clotting studies are an indication of DIC. Treatment must be prompt and the midwife should call for medical assistance and the on-call haematologist immediately.

Once the underlying cause and hypovolaemia are treated, blood products, such as red cells, fresh frozen plasma and platelets, are used to replace clotting factors. In some cases, cryoprecipitate is administered. NICE (2007) recommends the use of intravenous tranexamic acid and recombinant factor VIIa if clotting factors are normal, under the direction of a consultant haematologist.

Traumatic PPH

Approximately 10% of cases of PPH arise from a laceration of the genital tract (Anderson & Etches 2007). Occasionally, these are perineal tears or episiotomies. Lacerations involving the labia or clitoris often bleed freely. Deep lacerations of the vaginal walls, cervix and, exceptionally, lower uterine segment will produce severe haemorrhage. This is much more likely to complicate a difficult instrumental delivery, or may follow a rapid labour. Uterine rupture may occur in obstructed labour or if a scar ruptures.

Superficial bleeding points can be easily seen and treated by direct pressure. A laceration of the cervix is suspected if the bleeding begins immediately following the birth and continues steadily though the uterus is well contracted. It may be temporarily controlled by digital pressure or by applying a sponge or arterial pressure forceps. An obstetrician must be summoned and the laceration sutured. Tears to the upper part of the vagina, the cervix or the uterus are sutured under anaesthesia. In cases of severe haemorrhage from a ruptured uterus, it may be necessary to perform a hysterectomy.

A vulval haematoma may cause a PPH. This can occur following perineal repair with inadequate haemostasis or where there has been damage to vulval varicosities. There may be no obvious trauma and the perineum is intact (Baskett et al 2007). It appears as a localized swelling, usually one-sided, which looks tense and shiny. The pain may be severe and there may be signs of shock. A surprisingly large amount of blood may be present. The midwife must call for medical assistance and intravenous access must be secured, as replacement fluids may be needed. The haematoma should be drained under anaesthesia. Attention to perineal hygiene and pain relief is essential.

Following PPH

The mother may suffer from chronic iron-deficiency anaemia unless adequate treatment is instituted during the puerperium. She is more likely to develop puerperal sepsis and lactation may be poor. In severe and prolonged shock, the woman may develop anuria due to tubular necrosis. Another serious complication is anterior pituitary necrosis. If the mother survives, she will suffer from Sheehan’s syndrome, where lactation will not occur, owing to deficient prolactin secretion. Atrophy of the breasts and genital organs will follow.

The midwife should make the opportunity to discuss events with the couple. The sudden nature of the emergency often means that explanations given at the time are brief and hurried. The midwife should give them time to ask questions and can advise them about the likely causes and how future births may be managed.

Prolonged third stage

The risk of PPH is linked with a prolonged third stage of labour. The third stage is considered prolonged when it exceeds 30 minutes with active management, and up to 1 hour with physiological management (NICE 2007). The risk of PPH increases significantly with time, possibly doubling after 10 minutes (Magann et al 2005).

The incidence of retained placenta is approximately 3.3% (Weeks 2008). A retained placenta may be partially or completely separated but trapped in the cervix or lower uterine segment. In this situation, bleeding will occur from the placental site. If the retained placenta is completely adherent to the uterine wall, there may be no bleeding.

Causes

The following may cause delay in the third stage by interfering with the descent and expulsion of a separated placenta:

Other causes matching those of PPH:

Morbid adherence of the placenta

This occurs when the placental villi penetrate deeper than the decidua basalis. A combination of previous caesarean section and current placenta praevia are high-risk factors for abnormal trophoblastic penetration.

There are three types of abnormally adherent placenta:

The area of adherence may be focal, partial or total. Cases of focal or partial adhesion may be successfully treated by manual removal of the placenta, possibly followed by curettage. Attempts to remove a placenta percreta are likely to result in uterine perforation and haemorrhage. The obstetrician may perform a hysterectomy or may leave the placenta in place to be reabsorbed.

Management

After catheterizing the bladder, an attempt is made to deliver the placenta and membranes. Ultrasound may help to establish the position and adherence of the placenta. Nitroglycerine is effective in treating a trapped placenta by causing uterine relaxation (Bullarbo et al 2005). If an adherent placenta is suspected, oxytocin 20 iu in 20 mL saline injected via the umbilical vein following proximal cord clamping is recommended (Carroli & Bergel 2001). The NICE (2007:44) care pathway gives the management of retained placenta.

If these measures fail, manual removal of the placenta may be carried out under anaesthesia (Fig. 68.6). Blood is taken for cross-matching, and an intravenous infusion is commenced because there is a risk of severe haemorrhage occurring during the procedure.

Following manual removal of the placenta, uterine contraction is achieved by intravenous uterotonic drugs. If bleeding recurs or continues, bimanual compression may be required. Antibiotics are given, as manual removal is a highly invasive procedure with a risk of puerperal sepsis.

Though the activities of a midwife include the manual removal of placenta in an emergency (NMC 2004), in the developed world it is unlikely that the midwife would be required to undertake this.

The midwife must carefully monitor the woman’s condition in the postnatal period and refer her for medical attention if signs of uterine infection appear. The woman should be advised to have future births in hospital, as the risk of recurrence is high.

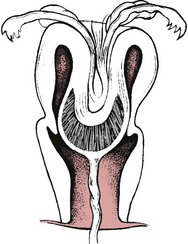

Acute uterine inversion

This is a rare but serious complication of the third stage of labour, where the uterus is partly or completely turned inside out (Fig. 68.7). The condition is associated with profound shock, and may also be associated with haemorrhage if the placenta has become separated from the uterus.

Causes

Diagnosis

Minor degrees of uterine inversion may not be recognized if there is only a slight indentation of the fundus. The woman may complain of pain and lochia will probably be heavy.

If the inversion is more serious, the woman will complain of severe pain and, on palpation, a hollow will be felt in the fundus of the uterus. Haemorrhage will occur if the placenta has separated.

If there is a complete inversion, the uterus will not be palpable in the abdomen and the inverted fundus will be visible at the vulva. The woman will complain of severe lower abdominal pain and may report a sensation of prolapse or ‘something coming down’. Neurogenic shock occurs owing to traction on the infundibulopelvic and round ligaments and compression of the ovaries (Calder 2000).

Management

Uterotonic drugs, if in progress, must be stopped. Where possible, the uterus should be replaced immediately, as maternal shock will increase and may become irreversible. Vascular congestion and oedema of the uterus may occur, making replacement more difficult the longer it is delayed. If immediate replacement is not possible and the uterus is outside the vulva, it should be gently replaced inside the vagina, if possible. Rough or prolonged digital manipulation will increase the accompanying vasovagal shock. The foot of the bed should be raised in order to alleviate shock by reducing traction on the infundibulopelvic ligaments. Intravenous access is required to take blood for cross-matching and clotting studies, and to commence intravenous fluid replacement. Catheterization is needed and intramuscular opiates are recommended. If the placenta is still attached, it must not be removed (Evans & B-Lynch 2006) as torrential haemorrhage may result. The woman must be transferred to theatre immediately.

In theatre, the uterus is replaced either manually or by the hydrostatic method under anaesthetic. The part of the uterus which inverted last is replaced first and the fundus last. A hand is placed on the abdomen to give counter pressure, otherwise the uterus may be pushed up too high. Drugs may be given to relax the cervical ring.

If this is unsuccessful, the hydrostatic method, as described by O’Sullivan (1945), is carried out. Once the obstetrician replaces the uterus in the vagina, warm normal saline is infused into the vagina via a rubber tube. This is held in place and the introitus sealed by the other hand. A ventouse cup attached to a giving set may also be used to produce a good seal (Ogueh & Ayida 1997). A better seal is produced when the woman lies with her legs together. The pressure exerted by the fluid distends the vagina and effects replacement of the uterus without aggravating the shock.

If other interventions fail, surgical correction via laparotomy is performed. Following replacement of the uterus, intravenous oxytocics are needed to ensure that the uterus contracts and bleeding is controlled. Further treatment for shock may then be required. If the mother survives, she may suffer from anuria and Sheehan’s syndrome as a result of shock. As the risk of puerperal sepsis is high, antibiotic cover is required.

The woman should be seen by the obstetrician 6–8 weeks after delivery in order to exclude chronic uterine inversion. The midwife should encourage the woman to carry out her postnatal exercises; referral to an obstetric physiotherapist may be helpful if the abdominal and pelvic floor muscle tone is particularly poor. As this condition may recur, the woman should be advised to give birth in hospital if she becomes pregnant again (Calder 2000).

Shock

Shock is a condition in which the circulatory system cannot maintain sufficient perfusion to the vital organs (WHO 2003). Cellular oxygen and nutritional requirements are not met and metabolic waste cannot be removed. The ensuing hypotension and reduced tissue perfusion may result in irreversible organ damage or death. Shock is classified according to its cause:

The latter three categories of shock are also known as distributive shock, which is characterized by peripheral circulatory abnormalities. The effects of shock may be exacerbated by pain, dehydration and exhaustion. The midwife is more likely to come across hypovolaemic shock.

Signs of deterioration

Most childbearing women are healthy and are unlikely to suffer harm provided that blood loss does not exceed the physiological volume expansion which occurs in pregnancy. However, after losing more than 35% of the total circulating volume, clinical signs of hypovolaemia will appear (Grady 2007). Midwives must be alert for changes in the condition of any woman in their care.

Initially, the signs of hypovolaemic shock are less obvious than those of the other forms of shock, and it is therefore more difficult to detect. The following signs indicate deepening shock which will affect all body organs and systems:

The latest CEMACH report recommends that all obstetric units develop an ‘early warning scoring system’ to aid in the timely identification, referral and treatment of women who develop complications that may lead to severe illness (Lewis 2007) (see website for reference of example).

Treatment

The midwife must closely observe the woman’s condition and call for obstetric assistance at the first sign of a rising pulse rate. Urgent resuscitation will be needed (airway, breathing, circulation). Once achieved, and the source identified and taken care of, the principles underlying treatment are as follows:

Septic shock

This is cardiovascular collapse due to septicaemia. Bacterial toxins are released, resulting in marked vasodilation. Blood collects in the capillary bed rather than returning to the heart. Cardiac output is reduced and peripheral failure ensues, resulting in tissue destruction, especially in the kidneys. Septic shock may follow puerperal uterine infection, septic abortion, intra-amniotic infection and urinary tract infection.

Signs

These are similar to other types of shock. However, there is earlier and more marked hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnoea and altered mental state due to metabolic acidosis. The woman may have pyrexia, along with hot, dry flushed skin. In the late stages of shock she will become hypothermic with cold clammy skin. Uterine infection may be accompanied by acute abdominal tenderness and scanty malodorous lochia. Multiple organ failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome and DIC may develop. Mortality can be high unless appropriate measures are instituted rapidly (Lewis 2007).

Management

This is similar to other types of shock. Additionally, the midwife must call for early medical assistance if there is any evidence of infection. If at home, the woman should be admitted to a hospital which has high dependency or intensive care facilities.

A midstream specimen of urine, high vaginal swab, wound swab and blood cultures are sent for bacterial investigation. Serum lactate, blood gases and clotting factors are measured.

A woman suffering with septic shock will need an intensive regimen of intravenous antibiotics, and any products of conception must be removed from the uterus. The midwife should pay attention to the woman’s personal hygiene and general comfort.

Amniotic fluid embolism

Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) is thought to be an acute anaphylactic-type response to amniotic fluid, fetal hair and debris in the maternal circulation. It is unpredictable and unpreventable, and occurs closer to term, during labour or delivery. Signs of AFE may also appear immediately after childbirth (Clarke et al 1995), although this is rare. The incidence in the UK is 1.8 per 100,000 maternities, with a mortality rate of 24% (Knight et al 2008) to 37% (Tuffnell 2005). Symptoms occur within minutes of the event and most deaths occur within 1 hour of the event. All cases of AFE are reported to the United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) (see website).

Risk factors include older, multiparous women, and cases where the physical barriers between the maternal and fetal circulation are mechanically disrupted (Abenhaim et al 2008). This includes caesarean section, artificial rupture of membranes, induction of labour, placental abruption, placenta praevia, uterine rupture and instrumental delivery. It may also be associated with multiple pregnancy or follow polyhydramnios.

In the above cases, the intra-amniotic pressure is increased and when the membranes rupture, amniotic fluid may be forced into the maternal circulation via the endocervical veins or the placental bed. Signs of fetal hypoxia commonly precede or accompany AFE (Thomson & Greer 2000).

Diagnosis is difficult but the UK (Knight et al 2008) and the US (Clarke et al 1995) AFE registries recommend that the following criteria must be present for a diagnosis to be made:

In the UK, an autopsy confirming the presence of fetal squames or hair in the lungs is also accepted (Knight et al 2008). However, women who have fetal material in their circulatory system do not necessarly develop AFE.

If the woman survives the initial event, the thromboplastin-like effects of amniotic fluid will cause a coagulopathy and she may subsequently die from coagulation failure. As the presence of intravascular amniotic fluid depresses myometrial activity, the uterus may become atonic and this will compound the haemorrhage due to coagulopathy (Clark 1990).

The midwife must immediately call for medical assistance and commence cardiopulmonary resuscitation. High concentrations of oxygen should be administered. An intravenous infusion is commenced and a central venous pressure line is inserted. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be needed. A caesarean section will be carried out as quickly as possible. The aim is not simply to salvage the fetus but also because adequate and effective resuscitation of the mother is better achieved when the uterus is empty.

Conclusion

The third stage is the most dangerous part of labour for the woman. Complications can arise with little warning. As the senior professional present at the majority of births in the UK, it is usually the midwife who has the responsibility for identifying the problem and beginning emergency treatment. Midwives must be aware of potential dangers, observe for signs of impending problems and know how to respond appropriately, as well as keep accurate records. Long-term consequences may be physical or psychological. The emotional needs of the parents must be addressed once the emergency is over. Parents will probably need to talk through the events with the midwife. The emergency often results in separation from the baby, which will cause distress. Breastfeeding may be more difficult to establish and the woman’s long-term relationships both with her baby and her partner may suffer.

Adequate emotional support should be available for the midwife and a discussion with the Supervisor of Midwives may be helpful.