Chapter 54 Bleeding in pregnancy

Introduction

Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy is always considered to be abnormal and should always be investigated. It may be extremely frightening for the woman, so must be managed with sensitivity, ensuring that the woman is fully informed and involved in her plan of care. An important part of the management lies within the diagnosis of the cause and in the accurate assessment and reporting of the woman’s previous and present history. It is also important to recognize that medical definitions and terms, such as ‘abortion’, will need to be explained. This term may have a different meaning for women and families.

Bleeding from the genital tract can be divided into two categories, depending on whether it occurs before or after the 24th week of pregnancy (Drife 2002).

Bleeding before the 24th week of pregnancy

Bleeding from the genital tract in early pregnancy – that is, before the 24th week – may be caused by:

Implantation bleeding

There may be a little bleeding when the trophoblast embeds into the endometrial lining of the uterus. The bleeding is usually bright red and of short duration. As implantation takes place 8–12 days after fertilization, the bleeding usually occurs just before the menstrual period is due. If mistakenly thought to be a menstrual period, this may confuse the expected date of delivery. A careful menstrual history is essential to detect probable implantation bleeding, thereby avoiding miscalculation of dates.

Abortion

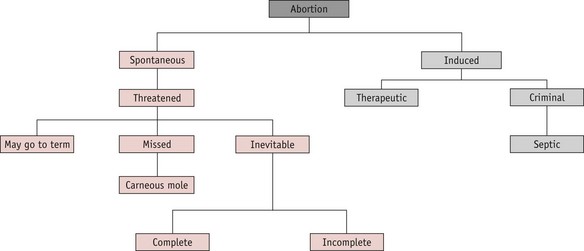

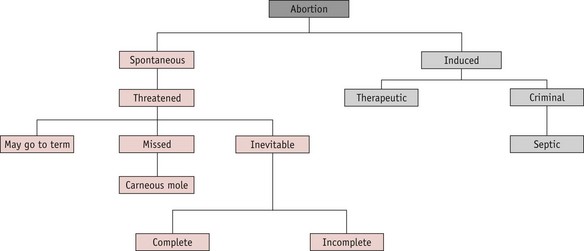

A pregnancy that ends before 24 completed weeks of gestation, and where the fetus is not alive, is termed an abortion. The classification is shown in Figure 54.1.

Spontaneous abortion

Approximately 15–20% of confirmed pregnancies end in spontaneous abortion, most of these occurring before the 12th week of pregnancy. Midwives should be aware that the term ‘abortion’ may cause confusion. Many women who have lost a wanted pregnancy find the word offensive and it should not, therefore, be used when talking to women about a pregnancy ending from natural causes. In these circumstances, the use of the word ‘miscarriage’ is more appropriate.

Causes

Despite detailed investigations, no cause can be found in the majority of cases.

Inevitable abortion

The key feature of inevitable abortion is cervical dilatation with an outcome of unavoidable pregnancy loss. The gestation sac separates from the uterine wall and the uterus contracts to expel the conceptus. This uterine activity causes discomfort similar to that of labour contractions. Speculum examination reveals a dilating cervix, possibly with products of conception protruding through. The gestation sac may be expelled complete (complete abortion), or in part, usually with placental tissue retained (incomplete abortion).

The midwife who is called by a woman with signs of inevitable abortion should arrange immediate care. The woman’s vital signs should be recorded and an estimate of blood loss made. If the fetus has been expelled and the woman is bleeding, local policies for the management of the third stage of labour and control of postpartum bleeding should be followed. Any products of conception passed should be saved for inspection. The midwife should refer the woman for medical care either by her GP or by a gynaecologist at her local hospital. If the bleeding is severe or the woman is showing signs of shock, a paramedic team from the local ambulance service should be requested. They will resuscitate the woman and stabilize her condition before transfer to hospital. In hospital, evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC) from the uterus may be carried out and a blood transfusion may be given if blood loss has been severe.

Medical management of inevitable or incomplete abortion is possible, using prostaglandin analogues such as misoprostol or gemeprost. Once the uterus is empty, vulval hygiene is important for comfort and to reduce the likelihood of infection: the woman should be advised to change her sanitary towels frequently and keep the vulva clean, using a bidet or shower if possible. All women who have required surgical evacuation should be screened for chlamydial infection (RCOG 2006).

If the breasts begin to secrete, the woman should be advised to wear a well-fitting brassiere in order to minimize discomfort. Cabergoline 1 mg may be prescribed by a medical practitioner or qualified midwife prescriber to suppress lactation. If the woman is rhesus negative, anti-D gammaglobulin is given within 60 hours of abortion to prevent isoimmunization and potential rhesus problems in subsequent pregnancies. Women who are non-immune to rubella may be given rubella vaccination at this time and advised to avoid the risk of pregnancy for the next 3 months.

Missed abortion (delayed abortion, silent abortion)

In this condition, bleeding occurs between the gestation sac and the uterine wall and the embryo dies. The uterus ceases to increase in size and as the presence of the retained fetus appears to inhibit menstruation, the woman may think that her pregnancy is continuing, although other signs of pregnancy have disappeared. The bleeding from the vagina varies from nothing, to a trickle of brownish discharge. As the signs of pregnancy gradually disappear, some women become aware that all is not well.

The diagnosis is confirmed by ultrasound. The uterus would eventually expel the fetus spontaneously, but this may not occur for some time. Treatment is usually to evacuate the uterus, either surgically or with misoprostol, either alone or in combination with methotrexate (Creinin et al 2003, Neilson et al 2006). ‘Expectant’ management may be offered: the woman is given the option of returning home for a few days to await spontaneous expulsion of the fetus.

If a well-formed fetus is retained in the uterus, it can become flattened and mummified as a fetus papyraceous (Fig. 54.2), rather than being reabsorbed. This is more commonly associated with a multiple pregnancy.

Recurrent abortion

This is a term used when three or more consecutive spontaneous abortions have occurred. Careful investigation should be undertaken to find the cause. Occasionally, the causative factors are different for each, with no clear single factor associated. However, some conditions may be implicated in recurrent pregnancy loss (Backos & Regan 2006).

Psychological effects

Many women experience a marked grief reaction following abortion and may require considerable counselling and support. Psychological distress may be severe and some women become clinically depressed. The grief experienced by the partner may be as intense as that of the woman, though he is less likely to receive support (Conway & Russell 2000). Staff should treat the parents with sensitivity. The couple may wish to see their baby and staff should take account of their wishes. The guidelines written by the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society are useful (SANDS 2009).

After the end of the 24th week of pregnancy, the infant must be registered as a stillbirth (Home Office 2008). Many maternity hospitals offer a funeral or memorial service for pre-viable fetuses and all must offer respectful disposal. In this situation, the hospital chaplain may be a valuable source of support and advice. Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC) can provide non-directive support and counselling for parents who have received high-risk antenatal screening results or diagnosis of a fetal abnormality (ARC 2009).

Induced abortion

This term refers to the deliberate termination of a pregnancy. Induced abortions are classified as therapeutic or criminal.

Therapeutic abortion

Therapeutic abortion has been legal in the UK since 1967, when the Abortion Act became law. This Act allows termination of a pregnancy if two registered medical practitioners are of the opinion that continuance of the pregnancy:

In current legislation, the upper gestation limit for legal termination is defined as the end of the 24th week (Dimond 2001, Human Fertilization and Embryology Act 1990). The only circumstances in which therapeutic abortion may be carried out after the 24th week are:

The law also allows for selective fetal reduction in multifetal pregnancy (see website),

Abortions after 24 weeks may only be carried out in NHS hospitals.

Criminal abortion

This is the termination of a pregnancy outside the terms of the Abortion Act, possibly by unauthorized and untrained persons, and is an offence punishable by law. The incidence has fallen sharply since the introduction of the 1967 Abortion Act. However, cases still occur: four such offences were detected in the year 2000–2001 (Home Department 2001) and seven in 2004–2005 (Home Office 2009). The abortion may be induced either by the woman herself or by some other person, by use of drugs or instruments. Whether successful or not, the action is illegal. The methods used may cause sudden death from haemorrhage, air embolus or vagal inhibition. Because of lack of asepsis, infection readily occurs and may lead to chronic ill-health or salpingitis and sterility (see website).

Septic abortion

Uterine infection may occur after spontaneous or induced abortion. It is more likely to occur following criminal abortion or spontaneous abortion where there are retained products of conception. The incidence of septic abortion has declined in countries that allow legal termination of pregnancy but it is still a cause of maternal death: five maternal deaths from sepsis following spontaneous abortion were recorded in the UK between 1997 and 1999 (Lewis 2001), and five in the triennium 2003–2005 (Lewis 2007) (see website).

Gestational trophoblastic disease (hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma)

Hydatidiform mole

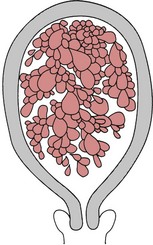

This condition occurs as a result of degeneration of the chorionic villi at an early stage of pregnancy (Fig. 54.4). Usually, the embryo is absent; occasionally, a hydatidiform mole may be found in a twin pregnancy alongside a viable fetus (Kauffman et al 1999). Molar pregnancy may be complete, with an intrauterine multivesicular mass composed of hydropic chorionic villi, or partial, where vesicular tissue is present, but less well developed, along with a fetus. Vesicle formation may occur within the placenta of an apparently normal pregnancy.

Signs and symptoms

Often, the minor disorders of pregnancy, such as nausea and breast tenderness, are more severe. The woman may complain of intermittent bleeding per vaginam from around the 12th week of pregnancy. When the mole begins to abort, there may be profuse haemorrhage. Pre-eclampsia may develop even in the early weeks of pregnancy. Severe nausea and vomiting may occur. On abdominal examination, the uterus is usually large for the period of gestation and may feel soft and doughy to the fingers. No fetal parts are palpable and the fetal heart is absent. There may be signs of mild thyrotoxicosis due to the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-like activity of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) which is secreted in large amounts by the molar vesicles. The diagnosis is suggested by the clinical findings and is confirmed by an ultrasound scan which will reveal no fetal parts but only a speckled or snowstorm appearance (Oats & Abraham 2004). Urinary or serum hCG levels wiil be high.

Treatment

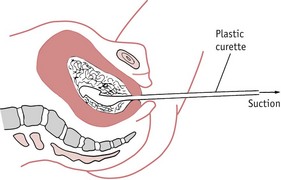

Once the diagnosis of molar pregnancy is confirmed, the uterus must be completely evacuated at once. This is achieved by careful suction curettage (see Fig. 54.3). Uterine contractions may cause molar tissue to enter the circulation via the sinuses of the placental bed. These emboli may set up metastatic disease in other sites, commonly the lungs. Medical termination should therefore be avoided. Unless the woman is haemorrhaging, oxytocic drugs are withheld until the uterus has been surgically emptied. A Syntocinon infusion may then be used to maintain uterine contraction and haemostasis. The woman should be registered at a specialist follow-up centre in London, Sheffield or Dundee (RCOG 2004a).

After treatment for hydatidiform mole, careful observation is required as approximately 3% of these women will develop malignant trophoblastic disease (choriocarcinoma). Partial moles are less likely to become malignant but still require follow-up (Seckl et al 2000). Serum beta-hCG levels are monitored fortnightly until the values fall to within the normal range. Urine samples are then normally tested every 4 weeks until 1 year after evacuation. In the second year of follow-up, urinary hCG testing is carried out every 3 months.

If any molar tissue remains in the uterus, it will continue to grow and may invade the myometrium. Perforation of the uterine wall is then likely and this will cause major internal haemorrhage. Signs that the mole is continuing to grow are indicated by the persistence of high hCG levels 24 hours after uterine evacuation and high levels 1 month after treatment. If the serum or urinary hCG fails to return to normal levels within 6 months or begins to rise again, the woman is at risk of malignant trophoblastic disease.

The woman must avoid another pregnancy until she has been discharged from the follow-up programme. Use of the oral contraceptive pill increases the risk of the development of invasive disease and should therefore be avoided until hCG levels have been normal for three successive months.

Choriocarcinoma

Choriocarcinoma is a malignant disease of trophoblastic tissue. It occurs following approximately 3% of complete moles (Seckl et al 2000). hCG levels will rise and the pregnancy test will become strongly positive again. Choriocarcinoma may occur in the next normal pregnancy following an evacuation of a mole.

As the growth infiltrates the uterus and vagina, the affected woman will experience increasingly severe pain. The condition will be rapidly fatal unless treated. The disease spreads by local invasion and via the bloodstream; metastases may occur in the lungs, liver and brain. Transplacental fetal metastases may occur during a pregnancy but this is very rare.

Choriocarcinoma responds extremely well to chemotherapy. Cytotoxic drugs, such as methotrexate, etoposide and actinomycin-D, are used singly or as combination therapy, and are nearly always completely successful. The woman should avoid another pregnancy for at least 1 year after the completion of treatment and will require hCG monitoring after any future pregnancy, as there is a risk of disease recurrence (Oats & Abraham 2004).

Ectopic or extrauterine gestation

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when the fertilized ovum implants outside the uterine cavity. In 95% of cases the site of implantation is the uterine tube and these are known as tubal pregnancies. Occasionally, the site may be the ovary, the abdominal cavity or the cervical canal, but these are rare. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 1 : 150 pregnancies (Baker 2006). Ectopic pregnancy is the major cause of maternal death before 20 weeks’ gestation in the industrialized world (Benrubi 2005, Lewis 2007).

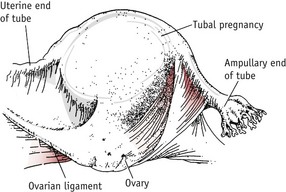

Tubal pregnancy

This is the commonest type of ectopic pregnancy and the incidence has increased two- to threefold in the last 30 years (Wiznitzer & Shener 2007). Tubal pregnancy occurs when there is a delay in the transport of the zygote along the fallopian tube. This may be due to a congenital malformation of the uterine tubes or more commonly to tubal scarring following pelvic infection. The ovum implants and begins to develop in the lining of the tube. The ampulla is the most common site (Fig. 54.5).

Although tubal pregnancy may occur in the absence of any significant history, there are certain risk factors (Lemus 2000, Wiznitzer & Shener 2007):

Diagnosis

Diagnosis based on clinical signs alone may be difficult because the clinical picture may appear similar to pelvic inflammatory disease or threatened abortion. Delay in diagnosis and treatment may contribute to maternal mortality and morbidity. The most accurate method currently available is a combination of serum hCG levels and transvaginal ultrasound scanning. hCG levels rise steadily in early pregnancy. Levels lower than normal or falling below the doubling time (the time in which serum levels can be expected to double) are indicative of ectopic gestation (Tin-Chiu et al 1999). The ultrasound scan may reveal a tubal mass or a fluid collection in the pelvis but is most useful for confirming the absence of an intrauterine sac. As the conceptus develops and grows, the tube distends to accommodate it.

Initially, the woman will experience the usual signs of pregnancy, such as nausea and breast changes, although amenorrhoea is not always present. The uterus will soften and enlarge under the influence of the pregnancy hormones. As the tube becomes further distended, the woman will experience abdominal pain and some vaginal bleeding. The blood loss is uterine in origin and signifies endometrial degeneration. Gastrointestinal disturbance such as diarrhoea and pain on defecation are also common signs (Baker 2006, Lewis 2007).

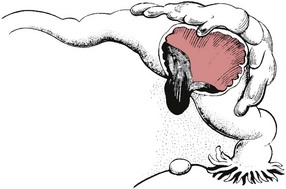

If the site of implantation is the narrower proximal end of the tube, tubal rupture is likely to occur between the 5th and 7th weeks of pregnancy (Fig. 54.6).

If the pregnancy is located in the wider ampullary section, the gestation may continue until the 10th week. Occasionally, the gestation sac is expelled from the fimbriated end (Fig. 54.7).

As the ovum separates from its attachment to the ampullary part of the tube, layers of blood clot may be deposited around the dead ovum to form a mass of blood clot which may remain in the uterine tube or be expelled from the fimbriated end of the tube. When the tube ruptures, there will be severe intraperitoneal haemorrhage and the woman will experience intense abdominal pain. There may also be referred shoulder-tip pain on lying down as blood tracks up towards the diaphragm. The woman will appear pale, shocked and nauseated and may collapse. The abdomen is tender and may be distended. Pelvic examination is usually exquisitely tender, especially on movement of the cervix. Ruptured ectopic pregnancy is an acute surgical emergency requiring immediate treatment.

Management

If ectopic pregnancy is suspected, a large-bore intravenous cannula (size 16 gauge) should be inserted and blood taken for cross-matching. The woman must be transferred to theatre as soon as possible. Laparoscopic salpingotomy may be performed unless the woman is suffering from haemorrhagic shock, when laparotomy is preferable.

If the condition is detected in the early stages, non-surgical management may be attempted with injections of prostaglandin F2a or systemic prostaglandin E2. Methotrexate may also be given, either intramuscularly or directly into the gestation sac (RCOG 2004b, Reis et al 2008).

Heterotopic or combined pregnancy

Heterotopic pregnancy occurs when a blastocyst from a multiple gestation implants outside the uterine cavity. It is associated with dizygotic twinning, and the extrauterine pregnancy is nearly always tubal. It may follow in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. The incidence is thought to be approximately 1 : 15000 and is likely to rise as the incidence of both multiple gestation and ectopic pregnancy rises. Diagnosis can be difficult and management options are limited by the presence of the intrauterine pregnancy. The ectopic sac must be removed but the uterus should be disturbed as little as possible and methotrexate must be avoided if the intrauterine pregnancy is to survive (Wiznitzer & Shener 2007).

Secondary abdominal pregnancy

Very rarely, when rupture of a tubal pregnancy occurs, there may be partial extrusion of the ovum into the peritoneal cavity but with enough chorionic villi remaining attached to the tube to ensure that the embryo does not die. Chorionic villi on the surface of the ovum then become attached to the neighbouring abdominal organs and the pregnancy continues with the fetus developing free within the abdominal cavity (see website). The fetus is at risk of severe growth restriction because of the relatively poor placentation and may also suffer pressure deformities as there is no protective uterine wall.

This condition is usually detected by ultrasound scanning but may be suggested by a persistently abnormal fetal lie and the fact that fetal parts are unusually easy to palpate. Delivery is by laparotomy. The placenta is usually left in situ to be absorbed, as an attempt to detach it may cause uncontrollable haemorrhage.

Ectopic pregnancy is a significant cause of maternal death and the incidence is rising. There were 10 reported deaths in the UK from this cause between 2003 and 2005 (Lewis 2007). The midwife must be aware of the associated risk factors and seek an obstetric opinion for any woman with signs or symptoms suggestive of extrauterine gestation without delay.

Bleeding from associated conditions

The following conditions may cause bleeding, although, strictly speaking, they are not bleeding of early pregnancy since the bleeding is not from the site of the pregnancy.

Cervical polyp

This is a small red gelatinous growth attached by a pedicle to the cervix, close to the external os. It may give rise to slight irregular bleeding.

Ectropion of the cervix

A cervical erosion is formed when the columnar epithelium lining the cervical canal proliferates owing to the action of the pregnancy hormones. The ectropion forms a reddish area on the cervix, extending outwards from the external os. It may give rise to a blood-stained discharge from the vagina. No treatment is necessary and the ectropion will recede during the puerperium.

Carcinoma of the cervix

Invasive cervical carcinoma is rarely seen in pregnancy, although cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) may occasionally be discovered if a cervical smear is taken. If the cervical cytology report suggests precancerous changes, colposcopy is performed to identify the affected areas and a small cervical biopsy may be carried out. Treatment is deferred until after delivery if the condition is not invasive.

Invasive cervical cancer is very serious as the disease may progress quickly. On vaginal examination, the cervix is hard and irregular and bleeds when touched. There may also be a purulent vaginal discharge. If the condition is discovered in the first trimester, the pregnancy may be terminated and treatment initiated. In the third trimester, the fetus is viable and may be delivered by caesarean section. Once the infant is born, the obstetrician may carry out a radical hysterectomy (Wertheim’s hysterectomy). Vaginal delivery is associated with a poorer prognosis for the mother as cervical dilatation may cause dissemination of tumour cells and metastases have been reported in episiotomy sites (Sood et al 2000).

A dilemma arises if the condition is discovered in the second trimester, because the fetus is unlikely to survive if delivered. The woman may choose to postpone treatment for a time to allow further fetal growth; however, the delay should be no longer than 4 weeks.

Bleeding in early pregnancy may occur for a variety of reasons. It is a serious sign and the underlying condition may be life-threatening. Any woman who reports vaginal bleeding during pregnancy must be referred to an obstetrician without delay.