Chapter 57 Sexually transmitted infections

Introduction

Most STIs are transmitted during sexual intercourse, non-penetrative genital contact, sex toys shared between partners or oral sex (BUPA 2007). Twenty-five types of STIs have been identified, although some – for example, vaginal candidiasis, pubic lice and scabies – can be acquired without sexual contact (Brook Advisory Centres 2008). Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, genital herpes simplex virus (HSV), genital human papillomavirus (HPV), non-specific infections, HIV, syphilis, HBV and trichomoniasis are the most common STIs.

Adverse trends in STIs in the UK are mainly attributable to rates of new HIV diagnoses and STIs in men who have sex with men. Although levels are relatively low, there has also been a steady increase in heterosexual HIV transmission, especially in the black ethnic minority. Most of the partners of infected black African and Caribbean people had probably been infected abroad (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007). Young adults (16–24 years of age) also appear to present a challenge as:

Controlling the transmission of HIV and STIs is a major public health challenge and midwifery practice involves responding to the challenge. Midwives are required to promote routine screening for HIV, HBV, and syphilis (DH 2003) to all pregnant women. Midwives encouraging sexual health and education during the booking visit may reduce transmission of infection, including mother-to-infant transmission, as well as facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of infected persons, which reduces associated morbidity and mortality. Midwives should ensure that women receive information about these screening tests, and advice about reducing the risk of STIs by reducing the number of partners and frequency of partner change, and using condoms correctly and consistently during sexual intercourse (HPA 2008a).

Most STIs, if detected early, are treatable and can be cured with antibiotics, for example, gonorrhoea and syphilis. However, patients with viral infection, such as HSV, experience recurrences, as the virus remains in the body and reactivates on occasions. HIV is more serious as currently no cure is available and the effects may be more devastating for a pregnant woman and her family.

This chapter will examine the midwife’s role and underpinning ethical principles in relation to HIV screening, including the complex issues involved in decision making for the woman (Box 57.1). These principles, including accurate information based upon evidence, may also be applied to the midwife’s role when offering and recommending screening for HBV and syphilis. These STIs, in addition to other common STIs, will be discussed, with reference to clinical presentation, pregnancy implications and management. An understanding of the clinical presentation and management of STIs will enable midwives to effectively meet women’s sexual health needs.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

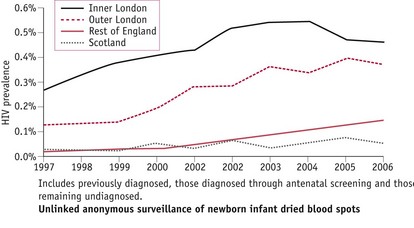

Unlinked anonymous surveillance of newborn infant dried blood spots shows that HIV prevalence in women giving birth varies widely nationally (Fig. 57.1) and is highest in urban areas, particularly London, where the prevalence has increased from 0.19% (200/106,407) in 1997 to 0.42% (502/119,614) in 2006 (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007). Women born abroad, especially in areas with generalized HIV epidemics, have a higher HIV prevalence than those born in the UK. One in every 2013 UK-born women giving birth in England was HIV-infected, compared with 1 in 138 non-UK-born women.

Figure 57.1 HIV prevalence among pregnant women by area of residence, England & Scotland (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007).

Disease progression

Sexual exposure is the primary method of spread of HIV infection worldwide. If left untreated, HIV damages the immune system, causing chronic and progressive illness as the infected person becomes vulnerable to a variety of infections (Bradley Hare 2006). Different stages of the disease have been identified (Pratt 2003):

HIV screening during pregnancy

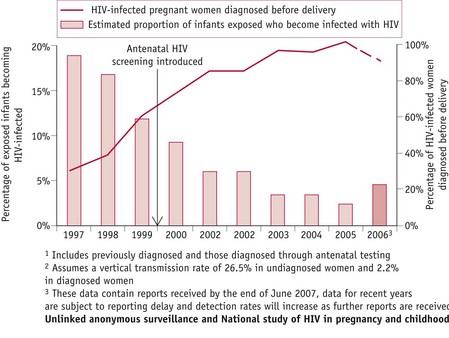

Since the implementation of routine screening during pregnancy, improved diagnostic rates for HIV have enabled infected women to make informed choices regarding interventions, reducing risks of mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) of HIV infection from 25–30% to less than 2% (RCOG 2004). By 2006, more than 90% of pregnant women were aware of their HIV infection, resulting in a MTCT rate of less than 5% in the UK, compared with about 20% in 1997 (Fig. 57.2) (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007).

Figure 57.2 Estimated proportion of HIV-infected pregnant women diagnosed before delivery1 and of exposed infants becoming infected with HIV2, England and Scotland (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007).

Beneficence

When applying ethical principles of beneficence (Ch. 8), the midwife should ensure outcomes of care result in ‘good’ being done to the woman and her baby. This entails informing women of the advantages of HIV testing during pregnancy, the benefits of which are listed below.

Preventing mother-to-child-transmission

Several well-conducted studies have shown that MTCT can be reduced by use of antiretroviral therapy, elective caesarean section (CS) and exclusively formula feeding the baby (Bott 2005). The HIV physician is responsible for determining treatment for individual women, taking into consideration maternal and fetal factors. For example, women with a low plasma viral load and a well-preserved CD4 T-lymphocyte count (website) can be treated either with single therapy (zidovudine) or with a combination of drugs referred to as HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) following a consideration of the benefits (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004) (Box 57.2). Women with advanced HIV (website) are likely to have symptomatic infection and falling CD4 T-lymphocyte counts and should be treated with a HAART regimen to improve maternal morbidity and mortality and prevent MTCT (RCOG 2004).

Box 57.2

Therapeutic options for women with a low plasma viral load and a well preserved CD4 T-lymphocyte count

| Option 1: Single-agent zidovudine regimen | Option 2: Short-term antiretroviral therapy regimen (START) |

| Benefits | |

| Benefits | |

British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004

Further research to evaluate the effect on MTCT and maternal health of planned CS for women who are taking HAART or who have very low viral loads is indicated in British guidelines. However, delivery by CS is recommended for other women. Women choosing vaginal birth benefit from discussing a birth plan with their midwife, including guidelines for vaginal and CS births, to ensure maximum benefit and minimum harm (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004) (Box 57.3).

Box 57.3

Guidelines for vaginal and CS births

| Elective CS | Planned vaginal delivery |

| • Clamp the cord as soon as possible after birth of baby | |

| • Test maternal blood at delivery for plasma viral load | |

| • Bath baby immediately after birth | |

British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004

Several studies have confirmed a 10–24% increase in MTCT of HIV when women breastfeed their babies (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). Transmission may occur throughout the period of breastfeeding, though the risk is influenced by breast milk virus load, which is highest early after delivery. Breastfeeding women have significantly higher median virus load in colostrum/early milk, compared with the mature breast milk collected 14 days after the birth of the baby (Rousseau et al 2003), and women with more advanced HIV are also more at risk of breast milk transmission (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). In the UK, midwives should advise all women who are HIV-positive to bottle-feed their babies to prevent MTCT (RCOG 2004). The Department of Health has issued guidance for healthcare professionals involved in supporting HIV-infected women to breastfeed their babies (see below).

To further reduce MTCT, HIV-infected women should be screened for other genital infections as early as possible in pregnancy and again at 28 weeks’ gestation (RCOG 2004).

Results from a comprehensive national surveillance study in England and Ireland conducted during 2002–2006 show that current options and treatment offered to pregnant women according to British guidelines appear to be effective in reducing MTCT. The overall MTCT was 1.2%, and it was 0.8% for women who received at least 14 days of antiretroviral therapy. Transmission rates were 0.7% for HAART with planned CS, 0.7% for HAART with planned vaginal delivery, and 0% for zidovudine monotherapy with planned CS (Townsend et al 2008). The transmissions that occurred despite woman taking HAART were mainly attributable to adherence problems and short duration of treatment.

Benefits for the mother

Early diagnosis of HIV improves maternal health and life expectancy as affected women benefit from being monitored and treated. The use of HAART has dramatically cut the number of deaths from AIDS-related illnesses and women benefit from PCP prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole, which is usually administered when the CD4 T-lymphocyte count is below 200 × 106/L. With appropriate treatment, affected people now have a near-normal life expectancy (BUPA 2008, RCOG 2004).

Benefits for the baby

Babies benefit from being followed up, and receiving appropriate treatment as necessary. Virologic testing of babies to diagnose HIV infection is recommended at 1 day, 6 weeks and 12 weeks of age (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). If the test results show a baby is HIV-infected, urgent referral to a specialist clinic enables early commencement of combination antiretroviral therapy. If the test results are negative, parents can be reassured that their baby is not infected with HIV, providing breastfeeding has been avoided. PCP prophylaxis is recommended for babies born to mothers at high risk of MTCT (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). A negative HIV antibody test result at 18 months of age will confirm that the child is uninfected (RCOG 2004).

Mortality, AIDS, and hospital admission rates have declined substantially in perinatally HIV-infected children in the UK and Ireland, paralleling the increased use of combination antiretroviral therapy. Mortality decreased by 80% between 1997 and 2001–02, AIDS progression decreased by 50% and hospital admission rates decreased by 80% (Gibb et al 2003).

Benefits for the family

Informed decisions regarding the current pregnancy in terms of effective interventions to prevent MTCT and planning future pregnancies may be made by women, possibly in consultations with their partners, or they may make informed choices to terminate the pregnancy if in their best interests. Preventing the spread of HIV infection may be through testing other family members for HIV and giving advice.

Non-maleficence

When applying the ethical principle of non-maleficence, the midwife should ensure that any act or omission does not result in harm. Being aware of the potential ‘harm’ (Box 57.4) facilitates discussion of individual concerns with women, who themselves must decide whether screening is in their best interests. Knowledge regarding potential effects of different treatments and interventions assists provision of optimum care.

Some women may be inclined to regard a negative test result as justification for an unhealthy lifestyle, described as the ‘certificate of health effect’ (Tymstra & Bieleman 1987). Screening may have adverse consequences should it lead to denial of the need to change ‘risky’ behaviour. McIntyre (2005) argues that women need to be informed that their risk of HIV acquisition during pregnancy is doubled, probably owing to biological changes, and messages to prevent infections should be reinforced. Midwives can therefore reduce ‘harm’ when discussing the implications of a negative test result. Also, women should understand that screening detects HIV antibodies present in the blood. The possibility of recent exposure or suspected exposure to HIV and re-testing later in pregnancy should be discussed, as a negative test result does not guarantee against newly acquired infection. It has been argued that further testing for HIV later in pregnancy, especially for women in an ethnically diverse area such as London, should be considered (Moses et al 2008).

Awaiting the results of HIV testing and receiving a positive result can be considerably stressful and midwives need to be sensitive to individual needs for support. Receiving an HIV diagnosis is a traumatic experience, resulting in reactions of shock, fear and anguish (Stevens & Tighe 1997). Women often experience unrelenting misery, escalating drug use and transmission risks, and destabilization of relationships, income and shelter. Other examples of harm include risk of rejection, isolation, domestic violence (Lester et al 1995) and suicide (Campbell 1995). Therefore, it is important that midwives are able to refer women to specialist counsellors and social workers as appropriate, to reduce the potential social and psychological ‘harm’. Details of HIV support groups may also be given (website).

Informing women of the 15–20% risk of vertical transmission is the same as telling them that 80–85% of babies will not be infected, and therefore the majority of mothers who accept interventions on offer will be exposing themselves and their babies to unnecessary treatment (RCOG 1997). Midwives can give women A guide to HIV, pregnancy & women’s health, which is freely available in different languages, to help them understand the different treatments, including different drug combinations, and the possible effects on the baby (i-base 2007).

Olivero et al (1997) warn of the potential toxicity of antiretroviral drugs and the need for long-term follow-up of children born to HIV-infected women. Monitoring the effects of perinatal exposure is particularly important in cases where these drugs have been administered during the period of embryogenesis, when teratogenicity is more likely to be a problem. Increasing numbers of women have been diagnosed with HIV before pregnancy and have been taking HAART prior to conception and throughout pregnancy. Long-term side-effects fall into four categories: teratogenic, carcinogenic, developmental and mitochondrial. The Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry, which detects major teratogenic effects for each licensed antiretroviral drug, has found no increased risk of birth defects so far among the overall population exposed to antiretroviral drugs throughout pregnancy, or among those exposed during the second and third trimesters, when compared with the general population. However, there was an increased frequency of birth defects when didanosine only was used and a significantly elevated rate of hypospadias after first-trimester exposure to zidovudine (Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry 2008). (See website for explanation of HAART.)

Short-term effects of mitochondrial (see website for relevant web-link) toxicity are rare, resulting in severe lactic acidosis, multisystem failure and anaemia. With appropriate care, affected babies are able to make a good recovery (Giaquinto et al 2001). Zidovudine has been associated with a higher incidence of neonatal haemoglobin concentration of less than 9 g/dL, although by 12 weeks of age this effect was no longer apparent (Connor et al 1994). However, a more recent study has reported a significant negative effect on haematopoiesis up to the age of 18 months (Le Chenadec et al 2003).

Some studies have shown a significant association between HAART and preterm delivery, especially before 34 weeks, and an increased risk of pre-eclampsia (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). Lactic acidosis, a recognized complication of HAART, may mimic the signs of pre-eclampsia. Signs of lactic acidosis include gastrointestinal disturbances, fatigue, fever and breathlessness. Other antiretroviral toxicities include hepatoxicity, rashes, glucose intolerance and diabetes (RCOG 2004).

Many HIV-infected women in the UK would prefer to breastfeed their babies if it was safe. Randomized controlled studies are currently being conducted in Africa to determine the safety of breastfeeding when mothers are on combination antiretroviral therapy (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008).

When HIV-infected mothers choose to breastfeed, under the Children Act 1989, courts have a statutory duty to treat the welfare of the baby as paramount. If the midwife’s duty of care to the mother conflicts with the needs of the baby, it is vital to ensure, with an interpreter if necessary, that the mother understands why bottle-feeding is recommended and explore reasons why a mother might feel unable to avoid breastfeeding. In exceptional circumstances, when a midwife is required to support an HIV-infected mother who persists in wanting to breastfeed her baby, the social worker, paediatrician and supervisor of midwives should all be informed. Accurate records of care should be kept. The UK Chief Medical Officers’ Expert Advisory Group on AIDS (2004) advises the following strategies to protect the infant from possible MTCT of HIV:

Informed consent

Women need to be aware of the implications of receiving an HIV diagnosis in order to decide whether to be tested, and, if necessary, make informed decisions regarding treatment and interventions (Ch. 8). Midwives must ensure that women are provided with relevant up-to-date information ‘in a way they can understand’ (NMC 2008). Leaflets, available in different languages, are helpful in facilitating this process (DH 2000).

Autonomy

Autonomy (Ch. 8) is inextricably linked with consent and entails facilitating a woman’s ability to formulate and carry out her own plans so that she is in control of her life and can act freely within the context of rational decision making (Downie & Calman 1987). Midwives must ‘respect and support people’s rights to accept or decline treatment and care’ (NMC 2008). Lack of feelings of autonomy and control may discourage some women from seeking antenatal care.

Confidentiality

A breach of confidentiality (Ch. 8) is particularly serious for women who are HIV-positive, because of the risk of discrimination. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC 2008) requires midwives to disclose information if they believe someone may be at risk of harm, in line with the law of the country in which they are practising.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV)

Routine screening for HBV during pregnancy was introduced in 1998 and the estimated uptake was 93% in 2005 (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007). Standards for screening aim to ensure immunization of babies born to infected mothers to reduce the perinatal transmission of this infection. Partners and children of infected women are offered screening and follow-up, with hepatitis B immunization as appropriate (DH 2003). Leaflets in different languages can be given to women to facilitate the process of informed consent (DH 2007) (see website).

Many people infected with HBV are unaware of their infection. Those who do experience symptoms commonly have a ‘flu-like’ illness and jaundice (DH & RCM 2000). Approximately 10% of infected people become carriers of the virus (Sira 1998) and 20% of carriers develop serious liver disease, such as cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (Wright & Lau 1993). Vertical transmission may occur at or around the time of birth (DH & RCM 2000), and up to 90% of infected infants become chronic carriers (Grosheide & Van Damme 1996). These infants are at risk of premature death from chronic liver disease. Immunization can prevent 95% of cases of such infants developing carrier status (Hadler & Margolis 1992).

Screening involves testing a blood specimen for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg). If the screening test is positive, confirmatory testing is undertaken. If infection is confirmed, tests for hepatitis B e-markers are carried out to determine whether the newborn baby should be given hepatitis B specific immunoglobulin (HBIg), in addition to hepatitis B vaccine.

Babies born to carrier mothers should be immunized with hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth. If the mother carries the hepatitis B e-antigen or has had acute HBV infection during pregnancy, the baby should also receive HBIg. Further vaccinations are given at 1 and 2 months of age. At 12 months, a booster dose is given, and follow-up testing should also be carried out (DH & RCM 2000). Breastfeeding is not contraindicated, therefore this should be encouraged and supported. Also, mothers should be referred to a specialist with expertise in liver disease.

Reflective activity 57.2

Find the local trust protocol for midwives offering and recommending HBV screening. What written information is given to infected mothers regarding when injections should be given to their babies, and who is responsible for administering each dose and follow-up appointments?

Syphilis

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, a spirochaete, which enters the body through tiny breaks in the skin of the external genitalia during sexual intercourse.

If untreated, the disease progresses through four consecutive stages:

During the primary or secondary stage of syphilis, MTCT will inevitably occur at any stage of pregnancy. Complications include miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, and congenital syphilis, and 50% of babies born to these infected women will die within 4 weeks (Heffner & Schust 2006).

UK pregnant women have been screened routinely for syphilis for many years, with an estimated uptake in 2005 of 95%. Increasing numbers of women have been diagnosed in recent years (from 268 in 2002 to 553 in 2006) and high screening uptake rates must be maintained to prevent future cases of congenital syphilis (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007). Penicillin is the treatment of choice in all but highly allergic patients.

Syphilis is not transmitted during breastfeeding, unless an infectious lesion is present on the breast (Genc & Ledger 2000). Midwives should ensure that women are given this information.

Gonorrhoea

Gonorrhoea is caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae (HPA 2008a).

Affected men commonly develop urethritis, with dysuria and/or a purulent urethral discharge. Many women are asymptomatic. Others present with dysuria and vaginal discharge from cervicitis or purulent drainage from the Bartolin’s glands (Heffner & Schust 2006). If untreated, it can cause chronic pelvic pain, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy and infertility (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007).

During pregnancy, gonorrhoea has been associated with low birthweight, premature delivery, preterm rupture of the membranes, chorioamnionitis and postpartum sepsis. Without treatment with antibiotics, MTCT can occur and 30–50% of babies will develop ophthalmia neonatorum within 3–14 days of life, which may cause blindness. Otitis media and nasopharyngitis may also occur (Heffner & Schust 2006, Mitchell 2004).

Genital herpes simplex virus (HSV)

Genital herpes is a lifelong disease, as HSV establishes a latent infection in the sacral dorsal root ganglia which can be reactivated when exposed to certain conditions, including fever, sun exposure and hormonal changes. There are two types of HSV (HPA 2010):

About 55% of people with genital HSV are asymptomatic and may be unaware that viral shedding, which commonly persists for at least 8–10 years, may contribute significantly to genital HSV transmission (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007).

Of those who do experience symptoms after initial infection (primary episode), over 80% present with symptoms of mucocutaneous infection around the infection site, including painful penile or vulval lesions or blisters, dysuria, urethral or vaginal discharge, and painful inguinal adenopathy. Other symptoms include fever, headache, malaise, urinary retention and proctitis. Aseptic meningitis occurs in about 12–30% of patients. No HSV antibodies are detectable in a patient’s serum during this acute phase, demonstrating that there has been no prior HSV infection. Others will present initially with symptoms suggesting the occurrence of genital HSV infection, which tends to be milder than a primary first episode, and HSV antibodies will be detectable in the patient’s serum. This is referred to as a non-primary episode.

Following the primary episode, HSV virions travel to the dorsal root ganglia of the sacral plexus, where they remain in a non-replicative state until reactivation. Recurrent episodes of genital HSV-2 disease occur when the virus is reactivated. There is a dramatic increase in viral DNA synthesis and the virus spreads back down the sensory neurons to the skin. Affected people experience painful breakouts of penile or vulval and cervical lesions. The duration of symptoms and viral shedding is much shorter with recurrences.

Maternal primary HSV has been associated with spontaneous abortion, low birthweight, premature delivery and stillbirth (Mitchell 2004). Life-threatening neonatal herpectic infections may also occur as the baby becomes infected from the genital tract of the mother at delivery. The risk of MTCT varies and is dependent upon the likelihood of the virus being shed from the cervix (Heffner & Schust 2006) (Table 57.1). There is also an increased risk of MTCT among immunocompromised women, such as those infected with HIV (Chen et al 2005, Hitti et al 1997).

Table 57.1 Risk of neonatal HSV infection

| Clinical scenario | MTCT | Risk of cervical shedding among women |

|---|---|---|

| Primary episode of HSV-2 | 50% | 90% |

| Primary episode of HSV-1 | 50% | 70% |

| Non-primary episode of HSV-2 | 70% | |

| Recurrent episodes | 5% | 12–20% |

Women with a primary episode of genital herpes during pregnancy are offered treatment with aciclovir, and delivery by caesarean section is recommended for women with primary episode genital herpes lesions at the time of delivery, or within 6 weeks of the expected date of delivery, to prevent neonatal herpectic infection (RCOG 2007).

Babies with localized or disseminated neonatal infection are treated with intravenous antiviral therapy. However, even with effective treatment, 70% of babies with disseminated infection will die. Survivors have a high risk of neurological complications (Mitchell 2004).

Chlamydia

There is a high prevalence of genital chlamydia infection among young heterosexuals in the UK (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007). Infection with the bacterium, Chlamydia trachomatis, can cause mucopurulent vaginal discharge, bleeding between periods, painful micturition and lower abdominal pain in women. Untreated infection, which is likely because 70% of women are asymptomatic, may cause chronic pain, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy and infertility (HPA 2008b).

Symptoms in men include discharge from the penis, burning and itching in the genital area, and painful micturition. Complications, which are rarer than in women, include epididymitis and Reiter’s syndrome. As 50% of infected men are asymptomatic, they may unknowingly transmit infection to a female partner. Early diagnosis is beneficial in preventing complications and reducing the spread of infection. England’s National Chlamydia Screening Programme enables many young people to access screening for chlamydia in a wide choice of settings, including general practice, contraception clinics and young people’s sexual health clinics. Infected people are treated with antibiotics such as azithromycin or doxycycline (HPA 2008b).

MTCT of infection can occur as the fetus passes through the birth canal of a woman who has not received appropriate antibiotic treatment (doxycycline is contraindicated in pregnancy) prior to delivery, causing the baby to be born with conjunctivitis or pneumonia. However, both are treatable.

Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis, a very common STI, is caused by Trichomonas vaginalis, a flagellated protozoan. Infected women commonly experience vulval itching, dysuria and vaginal discharge, which may be frothy yellow and have an offensive odour; occasionally, women complain of low abdominal discomfort; however, 10–50% are asymptomatic. Men commonly present with urethral discharge and/or dysuria, urethral irritation and frequency of micturition, although 15–50% are asymptomatic (BASHH 2007).

It is unclear whether pregnant women with trichomoniasis are more likely to give birth prematurely, or have other pregnancy complications. Metronidazole, given as a single dose, is likely to cure trichomoniasis, but it is not known whether this treatment will have any effect on pregnancy outcomes (Gülmezoglu 2002).

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Genital HPV infections are extremely common, particularly in the first few years after onset of sexual activity. There are 40 types of HPV. Many types cause infections which are asymptomatic and resolve without causing disease. Others are oncogenic or ‘high-risk’ types that cause cervical cancer. High-risk HPV infections are also associated with cancer of the penis, vulva, vagina, anus, mouth and oropharynx. Those that do not cause cancer are termed ‘low-risk’ types. Two of the ‘low-risk’ types cause genital warts (HPA 2008c).

The National Health Service (NHS) Cervical Screening Programme aims to detect pre-cancerous lesions and cervical cancers at early asymptomatic stages when they can be successfully treated (Table 57.2).

Table 57.2 The NHS Cervical Screening Programme

| Age group (years) | Frequency of screening |

|---|---|

| 25 | First invitation |

| 25–49 | 3-yearly |

| 50–64 | 5-yearly |

| 65+ | Only screen those who have not been screened since age 50 or have had recent abnormal tests |

To protect girls aged 12–13 years against infection with HPV 16 and 18 (associated with 70% of cervical cancers), HPV vaccination was introduced into the national immunization programme from September 2008, with a 2-year catch-up campaign offering vaccination to girls aged between 16 and 18 from autumn 2009, and to girls aged between 15 and 17 from autumn 2010 (HPA 2008c, NHS Screening Programmes 2008).

Vaginal candidiasis

Vaginal candidiasis is caused by a yeast, Candida albicans, which often inhabits warm moist areas of the body such as the mouth, vagina, perineum and groin. More common in pregnancy or after the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, infected women often have no symptoms, although some experience vaginal soreness and itching, a white curdy vaginal discharge and reddening of the labia. Midwives can reassure pregnant women that there is no evidence that this infection, commonly known as ‘thrush’, harms the unborn child.

Although candida may be sexually transmitted, recurrent infection is more likely to be a result of reinfection from the bowel. Women should be informed of preventive measures, including wiping from front to back and avoiding tight underwear (especially synthetics). In addition, women should be advised to avoid excessive washing, and use of bubble baths and perfumed soaps that may damage the vaginal natural protective flora (Young & Jewell 2001).

Topical imidazoles should be used for treating symptomatic vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy. A 4-day course will cure just over half of infections, whereas a 7-day course cures over 90% (Young & Jewell 2001).

Conclusion

Significant increases in HIV prevalence in UK-born women giving birth between 2000 and 2006 occurred. Routine screening for HIV, introduced throughout the UK between 2000 and 2003, continues to be a highly successful public health intervention. Midwives have a key role in offering and recommending screening for HIV, HBV and syphilis during pregnancy, enabling infected women to benefit from interventions. This improves health outcomes for women and their families, reducing further spread of infection. Women should receive relevant information regarding issues surrounding testing to make an informed choice. Specially designed leaflets are useful, and midwives’ roles are to ensure these are easily understood and different languages meet individual needs. Details of support groups may also benefit women who are diagnosed during pregnancy.

Midwives require appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes when providing care in relation to sexually transmitted diseases in pregnancy. Effectively working within a multidisciplinary context ensures maximum benefit and minimum harm for all women and families.